When Christmas Comes E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

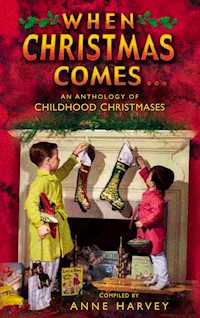

Anne Harvey recreates the magic and spirit of childhood Christmases through a collection of pieces of poetry, prose and illustration covering the past two centuries, reminding us of the excitement and anticipation felt by children at Christmas time. Their expectations and experiences at Christmas: the food and the presents, the preparation, the enigma of Father Christmas, the knobbly stocking, the magical tree, the sense of wonder as well as those moments of fear and disappointment, are all captured. Extracts from writers and artists including Quentin Blake, Alison Uttley, A.A Milne, and Tolkien vividly remember the excitement of hanging the stockings, making Christmas Puddings, singing carols, and decorating the tree.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 126

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2002

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

When Christmas Comes . . .

When Christmas Comes . . .

An Anthology of Childhood Christmases

compiled byANNE HARVEY

First published in 2002 by Sutton Publishing

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Anne Harvey, 2013

The right of Anne Harvey to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9484 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

In the Week when Christmas ComesEleanor Farjeon

Preface

Puddings and Pies

Pudding CharmsCharlotte Druitt Cole

from Days at WickhamAnne Viccars Barber

Christmas Plum PuddingClifton Bingham

from Father and SonEdmund Gosse

MincemeatElizabeth Gould

Menu for a KingEleanor Farjeon

Point of ViewShel Silverstein

The Father Christmas on the CakeColin West

Giving and Getting

from The Girls’ Friend, 1890

For ThemEleanor Farjeon

from Little WomenLouisa M. Alcott

Operation Christmas Child

from The Friday Miracle

Tonio’s GiftAnon

from Three HousesAngela Thirkell

Christmas Thank-You’sMick Gowar

AfterthoughtElizabeth Jennings

A Christmas ConundrumHerbert Farjeon

Santa Claus and Stockings

Christmas StockingEleanor Farjeon

from the New York SunVirginia O’Hanlon

The Night Before ChristmasClement C. Moore

The Night After ChristmasAnne P.L. Field

from Knickerbocker’s History of New YorkWashington Irving

Christmas DayAlison Uttley

What Billy WantedAnon

The Perfect StockingRose Henniker Heaton

The Waiting GameJohn Mole

Santa ClausFlorence Harrison

from How to be a Little SodSimon Brett

from It’s Too Late NowA.A. Milne

Letters from Fanny Longfellow

StruwwelpeterHeinrich Hoffmann

A Quick Note from Father ChristmasJohn Mole

Christmas ConundrumsHerbert Farjeon

Party Pieces

Home for the HolidaysAnon

The One I Knew Best of AllFrances Hodgson Burnett

Mistletoe, A Charade in Three ActsThe Brothers Mayhew

William’s Christmas EveRichmal Crompton

from A Nursery in the NinetiesEleanor Farjeon

The Ill-Considered TrifleAlan Melville

The Magic ShowVernon Scannell

Is Musical Chairs Immoral?Herbert Farjeon

WaitingJames Reeves

World Without EndHelen Thomas

The Holly on the WallW.H. Davies

The Children’s PartyEiluned Lewis

from How We Lived ThenNorman Longmate

Cards and Carols

from A Nursery in the NinetiesEleanor Farjeon

from Drawn from MemoryE.H. Shepard

A Little Christmas CardAnon

The Computer’s First Christmas CardEdwin Morgan

The Snow-ManWalter de la Mare

The Man They MadeHamish Hendry

The Children’s CarolEleanor Farjeon

from A Testament of FriendshipVera Brittain

Christmas DayWashington Irving

The Wicked SingersKit Wright

The Year I Was 8: A Christmas ChoirtimeAlexander Martin

The Nativity

CarolJohn Short

Jesus’ Christmas PartyNicholas Allan

A Christmas VerseAnon

Baa, Baa, Black SheepTraditional

from PeepshowMarguerite Steen

from A Room at the InnHerbert and Eleanor Farjeon

The Friendly BeastsTraditional

Christmas NightAnon

Nativity LamentJenny Owen

from 101 DalmationsDodie Smith

Trees and Trimmings

Advice to a ChildEleanor Farjeon

from Days at WickhamAnne Viccars Barber

The Song of the Christmas Tree FairyCicely M. Barker

from The Only ChildJames Kircup

from The Country ChildAlison Uttley

HollyChristina Rossetti

Poem for AllanRobert Frost

Emily Pepys’ Journal

Under the MistletoeAnon

The Christmas TreeJohn Walsh

Players and Pantomimes

Mummer’s SongTraditional

The MummersEleanor Farjeon

The Wednesday Group in St George and the Dragon

U is for UncleEleanor Farjeon

First TimeJan Dean

from The Only ChildJames Kircup

The PantomimeGuy Boas

DecemberRose Fyleman

In the Week when Christmas Comes

Eleanor Farjeon

This is the week when Christmas comes,

Let every pudding burst with plums,

And every tree bear dolls and drums,

In the week when Christmas comes.

Let every hall have boughs of green,

With berries glowing in between,

In the week when Christmas comes.

Let every doorstep have a song

Sounding the dark street along,

In the week when Christmas comes.

Let every steeple ring a bell

With a joyful tale to tell,

In the week when Christmas comes.

Let every night put forth a star

To show us where the heavens are,

In the week when Christmas comes.

Let every pen enfold a lamb

Sleeping warm beside its dam,

In the week when Christmas comes.

This is the week when Christmas comes.

Preface

Chill December brings the sleet,

Blazing fire and Christmas treat.

This is the final couplet in ‘The Months’, the poem written by Sara Coleridge for her 3-year-old son in 1841.

The word ‘Christmas’ immediately evokes childhood. I don’t believe, as I’ve heard said, that ‘Christmas is just for the children’, but I do believe that at Christmas time we can recapture the spirit of childhood. In this widely celebrated festival, and at the centre of Christian belief, at the close of the year, is a child, the Christ Child.

For me, Christmas 2001 went on until Easter 2002, because when everyone else had dismantled the tree, sent the cards for recycling, taken down the decorations, disposed of unwanted presents and left overs and finished the thank-you letters, I was still compiling this anthology. While children were back in uniform for the new school term and Valentine cards and daffodils were appearing, I was deep in nostalgic memories of Christmas, choosing seasonal poems and excerpts, poring over pictures of angels and robins, snowmen, stars and Santa Claus. This was a new experience, and through January, February and March I felt comfortably cut-off from reality. It was a warm, privileged time, although shadowed, I must admit, by knowing that a wealth of material would have to be left out.

Decisions had to be made. I wanted the anthology to draw on the many facets of a child’s expectation and experience: the food and the presents, the preparation, the enigma of Father Christmas, the knobbly stocking, the magical tree, the sense of wonder as well as those moments of fear and disappointment.

An anthology is a kind of cake or pudding or stocking, filled with assorted ingredients. Or perhaps it resembles a pie: I hope, like Jack Horner, you will find some plums in mine.

Anne Harvey

2002

Puddings and Pies

The real Jack Horner was possibly the steward of the Abbot of Glastonbury who, wanting to appease Henry VIII, sent a pie containing, not an edible plum, but the deeds of twelve manors. The plum pudding itself has a long history and dates back to the seventeenth century. Traditionally, ‘Stir-up Sunday’ is the last Sunday before Advent, when the Church of England collect begins, ‘Stir up, we beseech thee, O Lord, the wills of thy faithful people . . .’. This was interpreted as a reminder to ‘stir-up’ the mixture for Christmas puddings and pies, giving them time to mature. Children were taught to use only a wooden spoon and to stir the pudding clockwise . . . Everyone present must have a stir, in order of seniority.

Stir up, we beseech thee,

The pudding in the pot,

And when it is ready

We’ll eat it piping hot.

There are not so many round, cannon-like puddings nowadays, boiled in a cloth with steam filling the kitchen, and today’s mincemeat is meat-less, but we can still believe that any man, woman or child who eats twelve mince pies in twelve different houses during the twelve days of Christmas, will be happy from January to December the following year.

Pudding Charms

Charlotte Druitt Cole

Our Christmas pudding was made in November,

All they put in it, I quite well remember:

Currants and raisins, and sugar and spice,

Orange peel, lemon peel – everything nice

Mixed up together, and put in a pan.

‘When you’ve stirred it,’ said Mother, ‘as much as you can,

We’ll cover it over, that nothing may spoil it,

And then, in the copper, to-morrow we’ll boil it.’

That night, when we children were all fast asleep,

A real fairy godmother came crip-a-creep!

She wore a red cloak, and a tall steeple hat

(Though nobody saw her but Tinker, the cat!)

And out of her pocket a thimble she drew,

A button of silver, a silver horse-shoe,

And, whisp’ring a charm, in the pudding pan popped them,

Then flew up the chimney directly she dropped them;

And even old Tinker pretended he slept

(With Tinker a secret is sure to be kept!)

So nobody knew, until Christmas came round,

And there, in the pudding, these treasures we found.

from Days at Wickham

Anne Viccars Barber

Anne Viccars Barber followed her famous Buxton ancestors, who included Elizabeth Fry, in recording and illustrating childhood experiences. Her book Days at Wickham reveals some delightful Christmas memories.

Quite a long time before Christmas Nanny makes the Christmas puddings. We take it in turns to stir and make a wish. I always have a battle with myself as I long to wish for a lovely doll but instead I wish that my mother’s indigestion would get better. I do the same when I am lucky enough to have the wishbone of the chicken. I do wish her indigestion would hurry up and get better so that I could have the wish for myself.

Christmas Plum Pudding

Clifton Bingham

When they sat down that day to dine

The beef was good, the turkey fine

But oh, the pudding!

The goose was tender and so nice,

That everybody had some twice –

But oh, that pudding!

It’s coming, that they knew quite well,

They didn’t see, they couldn’t smell,

That fine plum pudding!

It came, an object of delight!

Their mouths watered at the sight

Of that plum pudding!

When they had finished, it was true,

They’d also put a finish to

That poor plum pudding!

from Father and Son

Edmund Gosse

Edmund Gosse recalls the Christmas following his mother’s death in 1857, when he was eight years old.

My Father’s austerity of behaviour was, I think, perpetually accentuated by his fear of doing anything to offend the consciences of these persons, who he supposed, no doubt, to be more sensitive than they really were. He was fond of saying that ‘a very little stain upon the conscience makes a wide breach in our communion with God,’ and he counted possible errors of conduct by hundreds and by thousands. It was in this winter that his attention was particularly drawn to the festival of Christmas, which, apparently, he had scarcely noticed in London.

On the subject of all feasts of the Church he held views of an almost grotesque peculiarity. He looked upon each of them as nugatory and worthless, but the keeping of Christmas appeared to him by far the most hateful, and nothing less than an act of idolatry. ‘The very word is Popish,’ he used to exclaim, ‘Christ’s Mass!’ pursing up his lips with the gesture of one who tastes assafoetida by accident. Then he would adduce the antiquity of the so-called feast, adapted from horrible heathen rites, and itself a soiled relic of the abominable Yule-Tide. He would denounce the horrors of Christmas until it almost made me blush to look at a holly-berry.

On Christmas Day of this year 1857 our villa saw a very unusual sight. My Father had given strictest charge that no difference whatever was to be made in our meals on that day; the dinner was to be neither more copious than usual nor less so. He was obeyed, but the servants, secretly rebellious, made a small plum-pudding for themselves. (I discovered afterwards, with pain, that Miss Marks received a slice of it in her boudoir.) Early in the afternoon, the maids, – of whom we were now advanced to keeping two, – kindly remarked that ‘the poor dear child ought to have a bit, anyhow,’ and wheedled me into the kitchen, where I ate a slice of plum-pudding. Shortly I began to feel that pain inside which in my frail state was inevitable, and my conscience smote me violently. At length, I could bear my spiritual anguish no longer, and bursting into the study I called out: ‘Oh! Papa, Papa, I have eaten of flesh offered to idols!’ It took some time, between my sobs, to explain what had happened. Then my Father sternly said: ‘Where is the accursed thing?’ I explained that as much as was left of it was still on the kitchen table. He took me by the hand, and ran with me into the midst of the startled servants, seized what remained of the pudding, and with the plate in one hand and me still tight in the other, ran till we reached the dust-heap, when he flung the idolatrous confectionery on to the middle of the ashes, and then raked it deep down into the mass. The suddenness, the violence, the velocity of this extraordinary act made an impression on my memory which nothing will ever efface.

Mincemeat

Elizabeth Gould

Sing a song of mincemeat,

Currants, raisins, spice,

Apples, sugar, nutmeg,

Everything that’s nice,

Stir it with a ladle,

Wish a lovely wish,

Drop it in the middle

Of your well-filled dish,

Stir again for good luck,

Pack it all away

Tied in little jars and pots,

Until Christmas Day.

Banana Mincemeat

A recipe for children’s parties from a 1930s women’s magazine

This is light and delicate, and makes a change from the ordinary kind. Skin 6 large bananas and mash them. Grate the rind of 2 lemons and squeeze their juice, chop 6 oz. of suet; mix all these together with 6oz. of currants, and a tablespoonful of orange-flower water; sugar may be added to taste, but ¼ lb will be about the right quantity. This mincemeat is best used quickly, and should be tied down with bladder or vegetable parchment.

Menu for a King

Eleanor Farjeon

In The New Book of Days, published in 1941, Eleanor Farjeon provided a scrap of fun or fancy, fact or fable for every day of the year. The book proved invaluable to school teachers . . . and to anthology editors.

The Country was France. The Year, 1611. The King was ten years old. And this was what he had for dinner.

Corinth raisins in rose water.

Egg soupe with lemon juice, 20 spoonsful.

Broth, 4 spoonsful.

Cocks combs, 8.

A little boiled chicken.

4 mouthfuls of boiled veal.

The marrow of a bone.

A wing and a half of chicken, roasted and then fried in bread crumb.

13 spoonsful of jelly.

A sugar horn filled with apricots.

Half a sugared chestnut in rose water.

Preserved cherries.

A little bread and some fennel comfits.

The fennel comfits were for the little King’s digestion.