Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

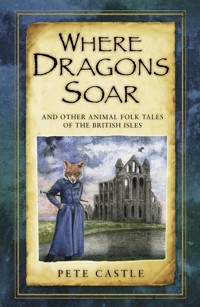

Within these pages are tales of scheming creatures and ferocious animals from across the British Isles, passed down through the generations. Amongst the more famous beasts of myth and legend, such as the Loch Ness monster lurking in Scotland's black waters and the Hartlepool monkey that was mistaken for a French spy, are the less well-known stories of the peculiar, fantastical and extraordinary. Discover the fox Scrapefoot and his run-in with bears, the fisherman's wife who was really a seal, and the two warring dragons hidden under Caernarfon – all brought to life by noted storyteller Pete Castle. Illustrated with unique drawings, these enchanting tales will appeal to young and old, and can be enjoyed by readers time and again.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 241

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

No animals were harmed during the research for this book

Illustrations by Pete Castle

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As always thanks must go to my wife Sue for support, patience and practical assistance, and for just being there.

To Anni Plant for the back cover photo.

To Alan Wilkinson for permission to quote from his ‘Hartlepool Monkey’ song.

To The History Press and my editors for making the production of this book so easy.

To all the singers and storytellers who’ve influenced me over the years and to all the audiences who’ve supported me.

To the long line of storytellers who made and preserved these stories over countless millennia.

To my Facebook friends who suggested stories and subjects, some of which were used and some rejected.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1

Here Be Dragons

The Knight and the Dragon

• A Sussex Dragon

• The Two Warring Dragons

• The Lambton Worm

• Assipattle and the Muckle Mester Stoorworm

• Nessie, the Loch Ness Monster

2

Man’s Best Friend

Greyfriars Bobby

• Gelert, the Faithful Hound

Black Shuck and Other Spectral Dogs

• The Suffolk Black Dogs

• The Aylesbury Black Dog

• The Black Dog of Lyme Regis

• The Black Dog of the Wild Forest

3

As Wild as a Wolf, as Wily as a Fox

Wolves

How Wolf Lost His Tail

• The Wolf of Allendale

Werewolves

An Almost Human Beast

• The Derbyshire Werewolf

• Reynardine

Old Daddy Fox

Chanticleer and Pertelote

• The Fox and the Cock

• The Fox and the Bagpipes

• Old Daddy Fox

• The Fox and the Pixies

• Scrapefoot

4

A Game of Cat and Mouse

Alien Big Cats

• The King o’ the Cats

• Why the Manx Cat Has No Tail

• The Cheshire Cat

• The Cat and the Mouse

• The Tale of Dick Whittington’s Cat

• The Pied Piper of Franchville

• The Four-Eyed Cat

5

Down on the Farm

The Roaring Bull of Bagbury Farm

• The Black Bull of Norroway

• The Farmer’s Three Cows

• The Dun Cow of Durham

• Four Animals Seek Their Fortune

6

Bread and Circuses

Stories of Showmen and Their Animals

• The Flying Donkeys of Derby

• Who Killed the Bears?

• The Congleton Bear

• The Hartlepool Monkey

• The Man, the Boy and the Donkey

• Jack and the Dead Donkey

• The Parrot

• The Frog at the Well

• Love Frogs

7

We Three Kings

How the Herring Became the King of the Sea

• Windy Old Weather

• The King of the Fishes

• The King of the Birds

8

Here Comes the Cavalry

The Lion and the Unicorn

• Grey Dolphin’s Revenge

• The Horse Mechanic

9 Hares, Horses and Hedgehogs

Oisin and the Hare

• The Heathfield Hare

• Hare or Human

• The Kennet Valley Witch

• The Hedgehog and the Devil

10

Magical Transformations

The Small-Tooth Dog

• The Seal Wife

11

Exotic Animals

The Woman Who Married a Bear

• Alligators

• The Wonderful Crocodile!

• The Tale of Tommy the Tortoise

• The Lion Says His Prayers

• The Two Elephants

• The Knight and the Dragon (reprise)

Bibliography

About the Author

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

Stories are slippery creatures. You can’t trust them.

They’ve been jumping on and off the page and into the mouths and ears of storytellers ever since time began. They’ve probably shared our hearths for far longer than dogs or cats or any other of our domestic animals. They don’t stay put in one place either. If a group of people move you can guarantee that some stories will smuggle themselves away and move with them. Even if it’s only a lone traveller visiting foreign parts, you can be sure a few stories will, like fleas, accompany him, and different ones will come back, so it’s impossible to pin them down as belonging to any one particular place or people. As soon as you try – as soon as you say ‘this story is native to this particular area’ – then you are sure to find a very close relation to it living happily in another community, in another country, or even on another continent!

If you are a storyteller you might think stories are like cats – you don’t choose them, they choose you! There were several stories I considered for inclusion here which refused to be pinned down. I offered them a home, but they just didn’t want it. They slunk away.

This is a collection of British folk tales but how long they’ve been British, or whether they’ve always been British, is a matter for scholarship and debate. At the end of the last Ice Age Britain was empty, so we, and our stories, are all immigrants. We gradually moved here at different times from different places and brought our stories with us. It’s impossible to draw a line and say the stories that came to Britain before that date are British and those that came after are imports, nor can we limit ourselves to stories that were invented on these shores because almost all stories are based on an idea from an older one.

So when deciding what to include, or not, it comes down to common sense. It’s easy to make a case for including some ‘imports’ because they have become so well known that they are almost naturalised as British. The stories of the Grimms and other nineteenth-century continental collectors have entered our canon and are often better known to the general public than the work of, say, Joseph Jacobs in England. I’ve avoided those where there is an alternative, more local, version. There usually is!

I thought long and hard about whether or not to include any of the fables of Aesop. Everybody has heard of them and their morals; allusions to them or quotes from them have entered our everyday language (i.e. we all know of ‘The Boy Who Cried Wolf’). They’ve been in print in English since they were published by Caxton in 1484 and have been retold over and over, but they are still known as ‘Aesop’s Fables’ and are considered to be Greek, so I decided against them. But a couple managed to get in. I told you they were sneaky!

We need a perpetual supply of new stories to counteract the trickle of stories that get lost. Some are literally forgotten, sometimes they date and become difficult to understand, or they become untellable because of changing attitudes and social mores. Therefore I’ve allowed myself to introduce a handful here, in the hope that they fit and take root.

I once read that animal stories are amongst the oldest stories in the world. That is not surprising. Our early hominid ancestors, hunter-gatherers on the plains of Africa, were surrounded by other animals and once they had moved out of Africa and become meat eaters on the steppes and tundra they were dependent on animals for food and clothing, and sometimes fuel and building materials as well. I often picture the first story ever told was when a ‘caveman’ arrived back at his cave looking tattered and torn and told his family about the huge, ferocious beast he’d just escaped. In the way of ‘fisherman’s tales’ the beast probably grew in repeated tellings and a mythological creature was born!

When the idea of this book was first suggested I leapt at it. I felt it was something I could really get my teeth into and enjoy doing (and I have!). Before I started any serious work on it I thought there would be so much material that I’d be spoiled for choice, that it might easily develop into two volumes … or more. But once I’d started work I realised that wasn’t quite the case. It’s true that there are thousands of folk tales about animals and many of them are well known to everybody – both people who are fans of oral storytelling and the more general public. The question is, though, are there thousands which I could argue are British folk tales about animals and the answer to that is ‘no’. Many of those that instantly spring to mind are European, or African, or American and definitely haven’t been naturalised as British.

Bearing all that in mind, I hope you enjoy the selection I’ve made. I’ve striven for balance – balance of recent and ancient tales; balance of tales from different parts of the country (I’ve managed to include parts which often get forgotten, like the Isle of Man) and balance of all the different animals. An early idea I had was to restrict myself to ‘animals’, in the sense of mammals (with the odd dragon thrown in for flavour!) but I gradually realised that I should include fish and fowls as well – there is too much overlap not to. The only restriction I have kept to is that they should be stories about animals, not just stories in which animals play a small part. If there are no people involved so much the better!

I hope you approve of my selection. One of the first things I did was to ask my Facebook followers what animal legends they knew of; what towns had animals associated with them. Many of the replies mentioned three or four of the stories I have included here, but most were creatures associated with football teams which don’t have any real ‘story’ to go with them. One of the most mentioned was ‘The Derby Ram’, but you won’t find that here because I dealt with it at length in my Derbyshire Folk Tales book, where you can also find the story of ‘The Bakewell Elephant’. I have included two stories from that book again here, though, because they were too important to miss – ‘The Small-Tooth Dog’ is probably the only British version of ‘Beauty and the Beast’, and ‘The Derbyshire Werewolf’ is one of very few British werewolf stories I’ve been able to find.

Several of the other stories have appeared, probably in slightly different form, in Facts & Fiction storytelling magazine, which I have edited since 1999. You might have heard me tell several of them as well.

Pete Castle,

Belper, Derbyshire,

2016

1

HERE BE DRAGONS

THE KNIGHTANDTHE DRAGON

Once upon a time a knight met a dragon.

‘I’m going to kill you,’ said the knight.

‘Oh, don’t do that,’ said the dragon, ‘and I’ll tell you a story.’

So he began:

Once upon a time a knight met a dragon.

‘I’m going to kill you,’ said the knight.

‘Oh, don’t do that,’ said the dragon, ‘and I’ll tell you a story.’

So he began:

Once upon a time a knight met a dragon.

‘I’m going to kill you,’ said the knight.

‘Oh, don’t do that,’ said the dragon, ‘and I’ll tell you a story.’

So he began:

Once upon a time a knight met a dragon.

‘I’m going to kill you,’ said the knight.

‘Oh, don’t do that,’ said the dragon, ‘and I’ll tell you a story.’

So he began:

Once upon a time a knight met a dragon … and so on for as long as you can bear it!

The most obviously ancient-seeming tales found in Britain are those about dragons and other mysterious beasts. (The fact that they are ‘ancient-seeming’ doesn’t necessarily mean they are actually ancient, of course.) It seems logical to start this collection with a few of those.

Stories and legends about dragon-like creatures are found all over the British Isles, often just as fragments explaining, say, the circular ditches around a prehistoric hill fort (very likely called Worm Hill), but we tend to associate dragons mostly with Wales or Cornwall or the more remote parts of the north. ‘Silly Sussex’, then, is not the most obvious place to start this first section, but that’s what we’ll do. (Silly in this sense is from the Anglo-Saxon ‘sœlig’, meaning ‘blessed’.)

A SUSSEX DRAGON

St Leonard’s Forest is, today, part of the ‘High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty’. It is a cosy, hospitable landscape which stretches from Surrey, through Sussex into Kent. It’s typical ‘Home Counties’, ‘Little England’, England’s ‘green and pleasant land’ personified. Above all, it is safe. But in the past it was the haunt of dragons!

Way back in the early years of the sixth century CE, St Leonard killed a dragon in the forest which was subsequently named after him. He was injured in the fray and lilies of the valley sprouted where his blood fell. (They still grow abundantly in some parts of the forest.)

He also banished all snakes from the area, but his cleansing was not absolutely perfect for, about a millennium later in 1614, a strange and dangerous creature was reported to be frequenting the overgrown hollows and ‘vaultie places’ of ‘unwholesome shade’ in the forest. Its home seems to have been near the village of Faygate but it was seen all over the area to within a few miles of the town of Horsham.

The creature was described as being a serpent or dragon about nine feet long, which left behind it a glutinous trail like that of a snail. The middle part of its body was thicker than the neck and tail, and there grew from its torso two large bunches ‘about the size of footballs’, which some people thought would eventually grow into wings. This suggests it was thought to be only a young dragon! The dragon was dark in colour, though the underneath tended to red, and round its neck it had a stripe of white scales. Descriptions are vague because the creature could only be seen from a distance.

Although it left behind it a snail-like trail it was by no means snail-like in its speed. If anyone dared to approach too close it would raise its neck and stare round, then, once it had spied its prey, it would race after them on its four stubby legs faster than a man could run. The dragon did not necessarily have to rely on its speed to catch his prey because from a distance of four rods (twenty metres) it could spit venom which caused the target to swell up and die. A man and woman who came upon the dragon by chance suffered in this way, as did the dogs set upon it by another man, as well as various cattle. Humans and cattle do not seem to have been the dragon’s favoured foodstuffs, however. Although it killed them, it left them uneaten and seems to have preferred rabbits.

No one seems to know what happened to this creature and it disappeared from legend, although as late as the nineteenth century children were warned to keep out of various areas of the wood for fear of ‘monstrous snakes’.

The source of this story is a pamphlet in the Harleian Miscellany with the wonderful title:

A True and Wonderful Discourse relating a strange and monstrous Serpent (or Dragon) lately discovered, and yet living, to the great Annoyance and divers Slaughters of both Men and Cattell, by his strong and violent Poison: in Sussex, two Miles from Horsam, in a Woode called St Leonard’s Forrest, and thirtie Miles from London, this present Month of August, 1614. With the true Generation of Serpents.

With a title like that they didn’t really need to write the story!

THE TWO WARRING DRAGONS

After a cosy, almost domestic, start in Sussex, let’s leap into classic ‘dragon lore’ for the next story. This is an ancient tale which has been told by many different people in many different times. Each telling is different and serves a different purpose – often political or nationalistic – depending upon the teller and the age. This is my telling, put together from various sources, which sets out to have no purpose other than to make a good story.

Way back in the earliest days of Britain, when there was no sense of one United Kingdom covering the whole island and no king who could command all the country; when there were no English and no Welsh; no Anglo-Saxons and no Celts; when the Romans had yet to bring their roads and walls and their Christian religion. Way back then, in the time of myths, there were two brother kings. Llefelys ruled a kingdom across the sea, in what we now call France, and his brother, Llud, ruled what is now southern England. They were good kings who ruled their kingdoms well and remained good friends. But Llud had a problem.

On the first day of every May, when his people should have been celebrating the end of winter with the raucous, bawdy, spring festival of Beltane, his kingdom was brought to a standstill by hideous screams and shrieks. These noises rang through the skies all over the kingdom and were impossible to ignore. They were so loud that they made the worst thunderstorm you have ever experienced seem tame and harmless. They were so terrible that they caused brave men to go pale and lose all their strength; lesser men lay down and died; women miscarried and animals became barren; the very crops in the fields withered and the new, fresh leaves fell from the trees.

Every year as Beltane approached, Llud’s people grew scared and they shut themselves away where they hoped they wouldn’t hear the screams – but there was nowhere to escape. They hoped and prayed to their gods that it wouldn’t happen again this year, but it always did, and every year the kingdom fell further into rack and ruin. No one could explain the screams, or their effect, so no one knew what to do to counteract them.

One year, when things had reached a terrifying low, Llud went to his brother Llefelys for help, to see if he could offer any explanation. Llefelys had at his disposal all the best brains in Gaul and could summon help from all over the continent and soon he was able to explain Llud’s problem. The shrieks and screams, he said, were caused by two dragons engaged in a never-ending battle. As they fought they roared out their pain and anger. To stop the disaster happening every year, Llud would have to stop the dragons fighting. They could not be killed, so he had to capture them and imprison them somewhere from which they could never escape.

Now that he knew what he must do Llud returned home and began making preparations to achieve his aim. The first task was to measure his kingdom from north to south and from east to west and find the dead centre. It turned out to be just outside the town of Oxford. There Llud had a huge watertight pit, or cistern, dug and when it was complete he filled it with mead. An enormous brocaded cloth was made to cover the pit.

On the eve of Beltane, Llud sat beside the pit and saw two terrifying, unimaginable beasts fighting. As they fought they changed. They went through every bloodthirsty animal known to man and many which aren’t. They were bears, they were lions, they were basilisks and griffons. They became hounds and wolves, leopards and endless coiling snakes. They grew large, they shrunk small. They tried to trick each other. As the night grew old they changed into dragons and soared into the air to continue their fight. As they swooped and battled they let out the deadly shrieks which had ravaged his kingdom for so long.

After a night of fighting in which first one and then the other dragon had seemed to have the upper hand, they both sank to the ground by the cistern where they changed into giant pigs. Smelling the mead the pigs plunged into the pit and quenched their thirsts with gallons of the intoxicating liquid. Then they collapsed in a drunken stupor. Llud was then able to bind them up in the brocaded cloth and have them transported away to the distant mountains of North Wales, where they were interred in a cave far under the ground where they could do no more harm.

Llud became a hero to his people and ruled them well for the rest of his life. They thought that the threat of the warring dragons was a thing of the past and gradually the suffering they had caused faded from memory. Centuries passed and new peoples came to the country, new wars were fought and new kings ruled. One of these was called Vortigern. Vortigern had made his stronghold in the mountains of Caernarfon in North Wales on an isolated, rocky outcrop. He called it Dinas Ffaraon Dandde, or ‘the fortress of the fiery pharaoh’. From there he ruled a wide area of land, but in order to make himself stronger and even more powerful he needed to expand and strengthen his castle. The trouble was, every time he constructed a new tower or a new wall, it cracked and tumbled down.

Vortigern consulted his advisors, all the wisest sages and cleverest magicians he had at his disposal, and they told him that the only remedy was to find a boy who had no natural father and to sacrifice him. But what kind of boy has no natural father? Vortigern eventually found one, a young lad called Merlin whose father was a demon or shapeshifter, so he was ‘no natural father’. Although he wasn’t a shapeshifter like his father, Merlin did have more than natural powers and he was able to explain that Vortigern’s advisors were wrong. Sacrificing him would make no difference. The towers and walls kept falling down, he said, because the castle was built over a vast cave in which two warring dragons were trapped. It was their writhing which shook the ground and caused the towers to fall.

Following Merlin’s advice Vortigern ordered his men to dig, and sure enough they opened up a huge underground cavern from which two vast dragons, one red, one white, soared into the skies and continued their age-long battle. All the people were terrified and fled, except Merlin, who stood by the cavern applauding them on. Eventually one of the dragons was defeated and fell to earth, where it died. The other gave a great roar of victory, transformed itself into a huge serpent and crawled off into the earth to await a time when it might return to aid one or other of the peoples of these islands.

Whether the victor was the red dragon of Wales or the white dragon of England depends, of course, on who is telling the story, so I’ll leave that to you to decide for yourself.

When is a Dragon a Worm?

The previous story depicts the classic dragon: a gigantic creature with wings, which flies through the air, breathing fire down on to its enemies and collects to itself a hoard of gold that it then guards jealously. That kind of dragon is sometimes found in British folklore, particularly in Welsh tales. It is also the kind of dragon that occurs in more recent fantasy fiction, from Tolkien onwards.

But the real British dragon is a worm – sometimes spelled ‘wurm’ or ‘wyrm’. The word comes from the Germanic languages and is the word for a serpent, a snake or a dragon. (I once stayed for a very short night at a hotel near the German/Austrian border called Hotel Wurm, which had as its sign a sort of ‘St George and the Dragon’ type picture. As I said, it was a very short night, they didn’t speak English and I don’t speak German, so I didn’t find out whether there was a local legend attached to it, but I’d bet there was. It’s a story found worldwide.)

There are plenty of worms in British folklore and it is quite a commonplace name. A quick look at major places in the road atlas comes up with about twenty towns and villages starting with Worm … some of those are thought to be named after a man named Worm/Wyrm (in other words they are Mr Worm’s town), rather than after creatures, but about half are places where snakes were found – Wormwood Scrubs being a prime example.

There is a Worm Hill near Washington in Tyne and Wear, and that is associated with this next famous tale …

THE LAMBTON WORM

Young Sir John Lambton was the heir to his family fortune and a large estate in County Durham. But he was not interested in estates, and only in fortunes if they meant that he could enjoy himself. Rather than study he preferred to hunt, and rather than go to church on Sunday he preferred to go fishing in the nearby River Wear. That is what he did one fateful Sunday.

On his way to the river young Sir John met one of his father’s old retainers, a man who had known him since he was a toddler so wasn’t scared of giving him a word of advice. He warned John that no good would come of fishing on a Sunday and he should go back and go to church as all respectable people do. John ignored the old man and went down to the river and set up his gear. It was a perfect morning for fishing and John was a skilled fisherman, but that morning he could catch nothing. (If you are a fisherman I expect you have had mornings like that.)

He could catch nothing … that is, until he heard the distant church bell ring out the end of the service and at that very moment he felt a tug on the line. Only a small tug, it’s true, and when he pulled it in he found on his hook a strange little creature, more like a worm than a fish. It was not much bigger than his thumb and it had nine tiny holes down each side of its head. John didn’t know what it was, he’d never seen a fish like it, but he was fascinated by it, so he took it home with him in a jug. By the time he’d got home, though, he’d lost interest. The fish wasn’t all that fascinating so he tipped it into a well.

Soon Sir John Lambton went off with other young men of similar rank to fight in the wars in Palestine – the Crusades. They were all hoping for excitement and glory. They wanted riches and adventures and Crusading seemed the surest way of finding them. They were gone for many years.

In the years that Sir John Lambton was away that little worm in the well grew and grew until it was too big for the well and it crawled off to live in the River Wear. At night it would come out and eat all the livestock it could find – cows and sheep and, if it was really hungry, it would rear up its head, poke it through the window of a house, and take small children sleeping in their cradles. Sometimes it would spend the day lazing in the sun with its tail curled round Penshaw Hill, or the nearby hill which now bears its name – Worm Hill.

Word of the monster worm spread near and far and many warriors came and attempted to win themselves glory by killing it. They all failed because any part of the worm they chopped off immediately joined back on and it became whole again. Even if a knight managed to chop the worm in half the two halves always managed to rejoin.

After many years in the Holy Land, Sir John Lambton returned home to find his estates in ruins and his lands barren and empty because of the depredations of the worm. He went into Durham and consulted an old wise woman who advised him on how he should set about killing the worm.

Following her advice, Sir John covered his armour with sharp spikes so that when the worm tried to coil round him parts of it would be cut off. He then went to face it in the middle of the River Wear so that the parts which came off would be swept away by the current and could not rejoin. The old woman also told Sir John that after he had killed the worm he should be sure to kill the first living thing he saw. If he failed to do this, a curse would fall upon his family and none of them would die peacefully in their beds for nine generations. To prevent this from happening Sir John arranged with his father that when the worm was dead he would sound his horn three times. His father would then loose young John’s hunting hound, which would run to him and be sacrificed.