Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Folk Tales

- Sprache: Englisch

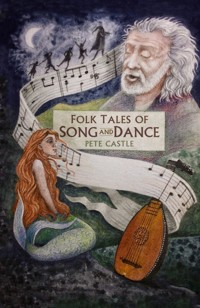

The life of the travelling musician hasn't changed much over the millennia. For a prehistoric harper, a medieval fiddler or a modern guitar player, the experience is pretty much the same: there are times when everything goes well and others when nothing does. But it's not just performing that can go wrong – listening can also be dangerous! Can you stop dancing when you get tired or must you keep going until the music stops … if it ever does? What happens if it carries on past midnight? What if it turns you to stone? Pete Castle has selected a variety of traditional tales from all over the UK (and a few from further afield) to enthral you, whether you are a musician, a dancer, or a reader who likes to keep dangerous things like singing and dancing at arm's length.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 265

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Pete Castle, 2021

The right of Pete Castle to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9694 5

Typesetting and origination by Typo•glyphix, Burton-on-Trent

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Glasgerion

Something to Tell ’em

Sandy/Sandra

On Minstrels, Bards and the Like

Spencer the Rover

Blondel the Minstrel

Robin Hood and Alan-a-Dale

The Two Sisters

Binnorie

The Raggle Taggle Gypsies-O

Johnny Faa

Singing Sam of Derbyshire

The Old Wandering Droll-Teller of the Lizard …

The Mermaid and the Man of Cury

The Mermaid of Zennor

Ion the Fiddler

The Guitar Player

The Devil’s Trill

The Fox and the Bagpipes

Colkitto and the Phantom Piper

The Phantom Piper of Kincardine

Underground Music

Ffarwel Ned Pugh

The Fairy Harp

Dance ’Til you Drop

The Hunchback and the Fairies

The Legend of Stanton Drew

Jack and the Friar

Jack Horner’s Magic Pipes

The Bee, the Harp, the Mouse and the Bum-Clock

Mossycoat

The Frog at the Well

Kate Crackernuts

Orange and Lemon

Hangman, or the Prickly Bush

Tom Tit Tot

Tiidu the Piper

The Pied Piper of Franchville

The Man Who Stole the Parson’s Sheep

Tapping at the Blind

Fill the House

The Show Must Go On

The Grove of Heaven

The Fiddler and the Bearded Lady

Joseph and the Bull

Bragi

King Orfeo

Dagda’s Harp

Etain and Midir

Glasgerion Part 2

Jack Orion

The Devil’s Violin

Afterword: Into the Twenty-First Century

Bibliography

About the Author

By the Same Author

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sue, of course, for being a friend, companion, support, wife and lover for over fifty years.

Nicky Rafferty for being the second person to read the book and for the enthusiastic response.

Taffy Thomas for ‘Fill the House’.

Madge Spencer for ‘The Guitar Player’.

Richard Martin for ‘Bee, Harp and Bum-clock’.

Katherine Soutar for the beautiful cover.

To everyone who has supported me over the years.

To everyone at The History Press for getting the book out in a difficult time.

INTRODUCTION

When I started work on this book I thought I was simply writing a book about song and dance but I soon realised I was writing a book about sex, murder, jealousy and just about all the other ‘seven deadly sins’!

I started playing guitar at about 14 or 15, not because it was a way of attracting girls – although I suppose that might have been a contributory factor, but just because I wanted to play music. I was very surprised that my parents agreed to buy me one. The guitar was very fashionable at that time but not a ‘respectable’ instrument. In the films of their young days – the 1930s/40s – the guitar was often an instrument used as shorthand for a disreputable character. In many of them, particularly Westerns, the baddy was foreign, lazy, smoked a cigar and strummed a guitar. That motif carried on into the McCarthy-era ‘Reds under the beds’ witch-hunts of the 1950s and ’60s against Communist infiltration in the entertainment industry in America. They produced leaflets on ‘How to Spot a Communist’ and two of the signs to look for were – they wear a beard and they play the guitar! Woody Guthrie took the opposite view with the slogan on his guitar: ‘This machine kills Fascists’. I have continued to play the guitar ever since, professionally since 1978, alongside storytelling, which came a bit later.

I suspect that musicians have always laboured under a disreputable reputation. It wasn’t invented for 1960s guitar players: it applied to 1860s fiddlers and 1260s harpists just as much – perhaps even to the bones players from some Stone Age culture. I have seen a musician described as ‘someone you would not want your daughter to marry’. That could be simply because it has always been a very unpredictable occupation, but there is more to it than that. Sailors are supposed to have a girl in every port and some musicians do as well. Conversely, musicians have always been seen as ‘glamorous’ and been prey for young women who wanted a trophy. That was particularly true in the 1960s/70s when being a ‘groupie’ was the aim of many teenage girls. I well remember being on the bus home from school, we’d just left the bus station, and the cry went up, ‘It’s the Searchers!’ and the bus emptied of girls at the next stop. It was the pop group The Searchers, who were playing in town that night and had gone out for a walk.

Dancing is similarly problematic. Professional dancers were often considered to be prostitutes whether they were or not. Dancing is frowned on if not banned outright by some religious groups. Even among relatively ordinary, liberal people some types of dancing are more accepted than others and the latest dance crazes always rub the older generation up the wrong way – probably deliberately!

So how do you write a book of folk tales like this? What is your aim? This is my fourth one for THP and my approach has gradually changed. With the first one – Derbyshire Folk Tales – I simply related the tales with nothing added, nothing taken away. You could have taken them off the page and told them. I gradually added a bit more of myself with each of the next two. This time I have used a variety of approaches. Some tales I have told straight or have just added short comments or introductions. A few though, I have allowed to move away from the simple folk tale as I would tell it. I have approached it more like a novella and included many more abstract ideas. This wasn’t really pre-planned. Once I started writing, some of the stories took over and demanded that of me. I have heard ‘proper authors’ say this and have never really understood it before … now I do. I hope the variety of approaches works for you.

One of my sources, T.W. Rolleston, in a rather prim 1910 book called The High Deeds of Finn, sums it up like this:

My aim … has been artistic, not scientific. I have tried, while carefully preserving the main outline of each story, to treat it exactly as the ancient bard treated his own material … that is to say, to present it as a fresh work of poetic imagination.

In other words, these stories don’t belong on the page – and definitely not in a museum – they should be out there on the tongue and in the world.

These stories came to me from here, there and everywhere – word of mouth, books, websites … BUT I avoided the best resource of all – other books in The History Press’ Folk Tales series! I wanted to avoid the versions of my contemporaries and colleagues so, even when I knew a particular teller had a version of a story in their book I made a point of not looking at it. If, therefore, you find one of my tellings is remarkably similar to yours then it is because a) we both went to the same source or b) great minds think alike!

The few stories that I have learned directly from contemporary tellers I did so with their knowledge and permission, and usually from them not their books.

So where and how did I find them? Some I have been telling or singing for many years – a few even pre-date my interest in storytelling! Some I knew of before I started writing but have never used; others I found by directed research – can I find a story about … and a few I came across by sheer chance when I was looking for something else. I have found that experience especially thrilling, particularly when it turns out to be a really good tale.

These stories cover a huge vista of space and time. They are almost all from the British Isles but that doesn’t mean some of them don’t feel ‘foreign’ to me because the British Isles includes England, Ireland, Wales, Scotland and the Northern Isles, where there is the added flavour of Viking influence and links with Scandinavia. The timescale ranges from prehistory to the present day. Of the few that I have imported from further afield, there is a Romanian tale that I use regularly and which fits alongside Glasgerion perfectly, and one from Estonia that I chanced upon and which shares themes and ideas with many others in the collection. It illustrates that people share the same stories wherever they live.

It also introduces an idea about which there has been a lot of discussion recently – cultural appropriation. I thought (or was it ‘worried’) about that a lot. I am quite happy reworking and re-telling English stories but when I get on to the very ancient Irish and Welsh legends that are treated by some as almost religious texts I’m not so sure. I am not an expert on the stories or the cultures. Am I misunderstanding something? Not getting the hidden meanings? I have tried to treat them as I would any other story and not allowed cultural baggage to get in the way. I hope my versions do not upset anyone.

Philip Pullman discusses that problem in an essay called ‘Magic Carpets’. He says:

Should we storytellers make sure we pass on the experience of our own culture? Yes, of course. It’s one of our prime duties … But should we refrain from telling stories that originated elsewhere …? Absolutely not. A culture that never encounters any others becomes first inward-looking, and then stagnant, and then rotten.

I hope this collection does its bit towards keeping our storytelling traditions alive. You can help it by taking them, making them your own, and telling them.

Pete Castle, Belper, 2020

GLASGERION

Glasgerion was the king’s chief harper. He was known throughout the land as the finest harper, singer and storyteller of his generation, and possibly of any generation, and his skill was so much above that of all the other bards that he was held in awe throughout the land. In Scotland he was known as Glenkindie and in Wales as Bardd Glas Geraint – Geraint, the Blue Bard.

When he played and sang, Glasgerion could charm the fish to leap from the sea or cause a stone to weep. When he sat in a quiet spot, the animals would gather round and lay peacefully together listening to his harp strings sing. He had musical conversations with the birds and each learned melodies from the other. In his favourite spot even the rocks had edged forwards to form a circle around his seat to hear him better. When he wanted them to, his songs could drive men to war or women to love. His stories could so entrance men that he could intervene in deadly feuds and by the time his story had ended they had forgotten what they were arguing about and went home arm in arm, the best of friends.

That was Glasgerion’s life and had been for many years. He had served his apprenticeship and learned his trade. Now he was in his prime – or past it, he sometimes felt.

One evening Glasgerion was sitting in his master’s hall letting his fingers play idly over the strings of his harp. Earlier he had entertained the assembled crowds with epic tales of heroes from the past, comic songs about foolish country folk, and erotic stories of love and courtship. He had finished with lively dance tunes and then slower, more languid airs until his master’s guests had gradually sunk into their seats and dropped asleep with their heads on the table, or slipped out of the hall and taken to their beds either to sleep or to make love.

Now he was playing mostly for himself. Soon he would retire as well. Those who were still awake were otherwise engaged with talking or flirting, the food and drink was almost finished and the fire in the central hearth had burned down to a dull red glow.

The only person who seemed to be still awake and paying any attention to Glasgerion was his Lord’s Lady. She sat, as she had for the past hour, with her eyes fixed on him drinking in every word he sang or spoke and every note he played. Glasgerion had been aware of her interest, had watched her watching him, and had not been able to prevent their eyes from meeting a few times.

At last she arose and walked quietly towards the staircase that led to her room. As she passed him she bent and whispered in his ear: ‘Before the day dawns and the cocks crow you must come and share my bed.’

She slipped through the curtain and Glasgerion was left wondering whether she had really said what he thought she’d said. Was he misunderstanding? Or mishearing? He could imagine her inviting some handsome young warrior to her bed but surely, he was too old …

He’d had his chances in the past but he’d never been a great womaniser. Sometimes he was just too naïve and didn’t understand the signals. He hadn’t always got the message; he’d doubted whether they had meant what he heard; he’d been too unsure of himself to take them up on it, or too scared of the retribution their family might make if he was wrong or if he was found out. Once he’d meant to accept the invitation of a woman he really fancied but he’d been unable to find her room and the next day she had acted as though he had done her the most terrible insult.

So why now? Why had this glamorous, desirable woman chosen him – a grey-haired, bent old harper.

Glasgerion thought back over the songs he had sung and the stories he had told that evening. He had been good, he knew that. But then he was usually good and he knew his trade so well that even when he wasn’t on top form he could make it appear that he was.

It must have been his music that had got him invited into her bed! He smiled to himself. That had been why he had chosen to become a musician in the first place! When he was a youth he and his friends thought musicians were glamorous and could have any girl they wanted. It was only when he had started on the path to becoming one that he had realised that if he wanted to succeed there was too much work involved to waste time on frivolous affairs with flighty girls.

So what had he played to work the magic on the most beautiful woman in the room? He had started the evening, as he always did, with a few light, frivolous items that were guaranteed to go down well with an audience that was still arriving and getting comfortable and were, maybe, not giving him all their attention. Then he had moved on to the big important ones, the ones that showed off his skill, and he mixed them up with a few dances. Towards the end when people started to fall asleep or leave for their beds, alone or not, he had lowered the mood again.

Glasgerion played his songs and told his stories and they worked their magic. But the evening did not end as it was supposed to with Glasgerion enjoying a night of bliss in the young Lady’s arms … the story continues at the end. Meanwhile:

Adapted from Child#67 – Professor Francis James Child’s The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. See note to Glasgerion Part 2 for more info. Learning from the master and following Glasgerion’s formula for a good set, I’ll continue with two simple, well-known stories that suggest that you shouldn’t leave the entertaining to the professionals. You must be ready to play your part.

‘Tell a story, sing a song, show your bum or oot ye gan’, as the old Scots saying goes!

SOMETHING TO TELL ’EM

A traveller arrived at a remote country inn one evening. He’d been on the road all day and he was tired. As soon as he entered, before he’d even had time to order a drink and a meal and book a room, the locals gathered round and started asking him where he’d come from and what he had to tell them.

‘What’s happening out there in the world?’ they wanted to know.

‘What news is there from the city?’

‘What should we know?’

They all spoke at once and tried to get his attention but whatever they asked he just shrugged his shoulders and said, ‘Nothing to tell you.’

‘Well, alright, if you’ve no news then tell us a story, you must have heard a story.’

‘No, nothing to tell you.’

‘Well a joke then. Are there any good new jokes going around? We haven’t heard a new one for ages.’

‘Nothing to tell you.’

‘How about a song? Have you heard any good ones? Do you play an instrument? Can you play us a tune?’

This went on and on with the locals trying their best to get some news or entertainment, or perhaps just conversation, from the traveller because they didn’t meet strangers very often. But his only reply was always: ‘Nothing to tell you.’

In the end they moved away and left him to his own devices.

When he’d eaten his meal the landlord showed him up to his room and he climbed into bed and was soon asleep.

In the middle of the night, when he was as fast asleep as you can be, he suddenly felt himself hauled out of bed, his nightshirt was pulled off and a warm, sticky liquid was poured over him. Then he heard his pillow being ripped open and he was sprinkled with feathers.

The result was that by the time he was fully awake he found himself lying on the floor, stark naked and covered with treacle and feathers. He looked around in amazement and saw the landlord standing in the corner laughing. ‘You’ll have something to tell ’em tomorrow night,’ he said.

And so there is the moral: you should always be prepared to tell a story, sing a song, tell a joke or even do a dance, for you never know when it will come in useful.

Trad English.

SANDY/SANDRA

This is another story that shows you should always have a tale to tell, a song to sing, a joke, or something else with which you can participate in a gathering. It also tells an unusual tale about how the hero/heroine found one!

Late summer and the harvest was in. It was a time for rejoicing and relaxing before the cycle started all over again and the workers had to toil away to get the fields prepared ready to plant the seeds for next year. Before that though, there was the Harvest Supper, a highlight of the year. The Master always provided plenty of food and drink and everybody ate and drank as much as they could. It was a time for letting your hair down and, possibly, doing things you later regretted – rather like an office party today.

All afternoon the men had been preparing the barn: it had been swept and green branches and ribbons hung around the walls. Then a long table was erected down the length of the building and chairs and benches brought in. Candlesticks and lanterns were placed on the tables and hung from the beams. There was also a large barrel of beer, which was the most important thing for some of them! Meanwhile, the women had been busy cooking and laying out plates and bowls.

Then, when it was all ready, there was a hiatus while everyone went off to prepare themselves. The men washed and shaved, oiled their hair and put on their best clothes, for they were hoping to impress the women and girls. They in turn were doing each other’s hair, sharing bits of make-up and seeing whether they could still fit into last year’s dresses and swapping with each other if they couldn’t. They were as eager to impress as the men were and the unmarried ones had the same hopes as the men, although perhaps not quite so openly! A tumble in the hay at the end of the evening was almost part of the ceremony and there were always a few women who found themselves ‘in trouble’ in the weeks afterwards.

At last the time came and everyone made their way to the barn and took their seats. There was a recognised but unspoken seating plan – the Master and Mistress were at the top of the table, the farm manager had pride of place at the foot, and the workers sat down the sides with the most senior at the head and the youngest at the foot where the manager could keep them in order.

Before anyone took their place though, the ‘mow’ – the Harvest Queen – made from the last sheaf and dressed to look like a woman with a crown of flowers on her head, was ceremonially carried in and seated on a throne-like chair to preside over the event.

Then grace was said and before the food was served the Master threw a purse of coins on to the table and announced that it would go to the person who could tell the best story, sing the best song, or otherwise entertain the guests in the most enjoyable way.

‘Eat first,’ he said, ‘and while you’re eating you can be planning what you are going to do. And it’s no good saying you can’t do anything because everyone has to take part. If you’re not going to do something then leave now, before you’ve eaten.’

Most of the crowd had already decided on their party piece, of course, because this happened every year. It was tradition that the farm manager always sang ‘To Be a Farmer’s Boy’, and three or four of the milkmaids got together and sang a hymn. Everyone else managed to do something but some of the younger ones were taken by surprise and didn’t know what to do at first.

One of these was young Sandy. It was his first experience of this and the idea terrified him. He was a big lad but very shy and innocent. He never said very much and only spoke when he was spoken to. The idea of standing up in front of all these people who he had to work with every day and trying to tell them a story was beyond him. He didn’t quite burst into tears but he stood up, red in the face, and stuttered, ‘Sir, I can’t do it. I haven’t anything to do. I don’t sing and I don’t know any stories.’

‘Then you can leave now,’ said the Master. ‘Go on, get out and don’t come back until you have something to entertain us with.’

Sandy stumbled shamefaced to the door and crept out, well aware of everyone looking at him and imagining he could hear the girls sniggering. How on earth could he face them tomorrow?

Without really thinking where he was going, he shuffled down the track that led to the river. There he found an old boat tied up. It was one that wasn’t used anymore and the bottom was full of water. It didn’t look too rotten though. Sandy pulled some brambles away and stepped in. Luckily he was wearing his tackety boots – heavy boots with hobnails in the soles to stop them wearing out. They were the only boots he had and they kept the water out and stopped his feet from getting wet. Just for something to do, Sandy reached under the seat and took out an old tin can that was kept there to bale water out. He started to bale and soon the water had almost gone. The boat seemed quite sound, no more water was coming in. Then he felt a jolt as it moved away from the bank. It was moving by itself with no help from him. Sandy wasn’t scared but he was a bit worried because he didn’t have any oars, but the river wasn’t running too fast and he didn’t think he would come to harm. The boat kept going, moving towards the middle of the river as though it was being steered by some invisible force. Now Sandy did begin to worry. He didn’t want to go too far. He’d never been down the river and didn’t know where it would take him. He’d never been across to the other side either. As he looked around wondering what to do he glanced at his legs and, instead of corduroy trousers and great big boots he saw a skirt and dainty shoes. He looked over the side of the boat at his reflection and a woman’s face with red lips and long, curly hair smiled back at him! He felt around his body and, although he was not that familiar with women’s bodies, he knew enough to realise that he now had one.

Then, suddenly the boat grounded on the far shore. Sandra jumped out and tried to pull it up out of the water so that it didn’t drift away, but she wasn’t strong enough. At that moment a young man came by and offered to lend a hand. He pulled the boat up on to the beach with no trouble at all and, seeing that the young woman seemed upset and confused, he took her back to his house, which was nearby. After a hot drink and a bowl of soup, Sandra began to feel better. It also seemed less strange to be a woman.

Because she was still muddled, had nowhere to go, and didn’t even know where she was, the young man said she could stay the night. He gave her his bed while he slept downstairs in front of the fire.

When morning came, Sandra still had no idea what to do, so she just stayed. She stayed for days and weeks and months and in that time she and the young man fell in love. After a while they got married and then they had a baby and they were very happy. Sandra had completely forgotten her previous life and it was as if she had always lived there.

Then one day she went out for a walk, just to get a breath of fresh air, and her feet took her down to the riverbank where she saw an old boat. She had no memory of ever having seen the boat before but she stepped into it and felt under the seat and pulled out an old can. She started to bale and the boat gave a jerk and drifted away from the shore. There were no oars and Sandra was terrified. She started to scream and yell and call for her husband, ‘Oh my husband, Oh my baby. Oh my husband, Oh my baby.’ He came rushing out but by now the boat was too far away and he could do nothing. Sandra slumped on to the seat and put her head in her hands … and felt a stubbly beard on her chin. When she looked down she saw corduroy trousers and great big boots. A few minutes later when the boat ran ashore, he was still shouting, ‘Oh my husband, Oh my baby. Oh my husband, Oh my baby.’

Sandy was still shouting when he reached the barn where the harvest song was in full swing …

Then drink, boys, drink!

And see that you do not spill,

For if you do, you shall drink two,

For that is our Master’s will …

Then the crowd began to thump on the table while the person whose turn it was downed his glass of ale and Sandy opened the door … ‘Oh my husband, Oh my baby. Oh my husband, Oh my baby.’ he yelled and silence fell as everyone turned to look at him.

The Master rose and went to him and put his arm round him. ‘Sandy, what’s happened? Where have you been? What are you shouting about?’

He gave Sandy a glass of ale to calm him and insisted on Sandy telling everyone what had happened.

So Sandy told them the story that I have just told you and the Master said, ‘Well, that’s the best story we’ve had all night. I don’t know how you came up with it but it deserves the prize,’ and he gave the purse to Sandy.

Sandy went and sat in a corner and didn’t say another word all night but he had a lot to think about.

A transgender story usually known as ‘Tackety Boots’ that comes from the traveller community in Scotland. When I started to write it, it took over and insisted on expanding!

ON MINSTRELS, BARDS AND THE LIKE

Minstrels, bards, troubadours, jongleurs or just plain street singers … and, for that matter, folk singers and storytellers of the present day, have all played a role in both preserving the old traditions and adding new material to them. In this book you’ll find a mixture of stories, some of which Glasgerion himself might have known and performed, alongside some much more recent material of which I hope he would have approved.

Glasgerion is described as a ‘bard’. A bard was much more than just a musician or storyteller. He was also a verse maker, a composer, a story maker, a historian, a genealogist and a teacher. I don’t know whether there were ever female bards, I suspect not, but in the much more informal environment of the family today it is usually one of the women folk who hold the family history, literally sometimes in the form of the photograph albums.

A minstrel or bard would need a rich patron if he was to make a good living but sometimes the life of a street entertainer was the lesser of two evils. If you could make however humble a living by travelling from town to town or fair to fair entertaining people with songs, stories or animal acts it might have seemed better than staying put and starving. But then perhaps, after a while, the gloss would wear off and you would begin to miss your home and family and decide it wasn’t so bad after all, as this song describes. I love the image of the children rushing out to meet him with their ‘prittle-prattling stories’.

SPENCER THE ROVER

These words were composed by Spencer the Rover

Who had travelled Great Britain and most parts of Wales,

He had been so reduced which caused great confusion

And that was the reason he went on the roam.

In Yorkshire near Rotherham he had been on his rambles,

Being weary of travelling he sat down to rest,

At the foot of yonder mountain there runs a clear fountain,