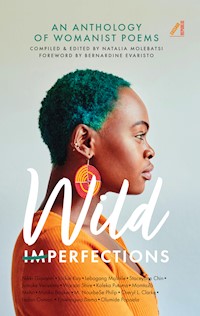

Wild Imperfections E-Book

17,94 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: CASSAVA REPUBLIC

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Featuring the work of Black women poets from Botswana to Brazil, in this collection, we encounter ancestors who made love, just for the sake of love, and women who die with each orgasm while attempting to mark the extent of their own humanities. This is for the nuns, the singers, the clowns, the diviners and the conjurers who reject the constant attempt to clean up history. The wildly imperfect women of slick braids, shiny skin and succulent lips, building new homes from clouds for future legions. Here congregate the women, womxn and womyn who do not believe in tough love that disguises hurt just to prove a point. They dance with the dead with exquisite feet, cheekbones high, reflecting their mothers' smiles. Because no one claps for martyrs, these dirty/pretty women learn to walk cities like they own them, choosing the battles of their hearts. If this collection teaches anything, it is that love is always messy, that our sacrament requires wet wipes and that we are just flesh and bone honing practice.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

iii

WILD IMPERFECTIONS

An Anthology of Womanist Poems

Compiled and edited by Natalia Molebatsi

WOMANIST

From womanish. (Opp. of “girlish,” i.e. frivolous, irresponsible, not serious.) A black feminist or feminist of color. From the black folk expression of mothers to female children, “you acting womanish,” i.e., like a woman. Usually referring to outrageous, audacious, courageous or willful behavior.

[…]

Womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender.

– Alice Walker’s Definition of a “Womanist” from In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose ©1983vi

CONTENTS

xiiixiv

FOREWORD

by Bernardine Evaristo

Wild Imperfections is testament to a worldwide network of Black women writers who interconnect on multiple levels, even though we may not know one another in person. While the physical boundaries of our nations might sometimes be hard to circumnavigate in person, appearing as impenetrable walls, we are nonetheless free to communicate with one another in myriad ways without the requirement of prohibitive finances or restrictive visa requirements.

This multi-generational, cross-cultural anthology is one such point of connection, one which is infused with multiple perspectives, aesthetics, preoccupations and sensibilities. It offers up a broad sense of community between Black women writers who are consciously interrogating what it means to be human from our unique perspectives. The poets here pour their responses and energies into poetic forms. Some are polemical poets, drawing on the orality of our literary history, others are more intimate, digging deep into our psyche, our emotions, our lives. It was a powerful experience reading the range of voices in this book and encountering so many women whose work I know, some of whom I know personally, or whose paths have crossed mine in the past. Whether friends, colleagues, acquaintances, or simply fellow writers, we meet in the page of each other’s books. We meet on tour at festivals or conferences where we might share a stage or a green room. We teach one another’s work in the classroom or lecture hall. And some of us mentor the next generation who are coming up behind us into a more inclusive climate than the one we ourselves experienced. We participate in cross-art-form projects, become editors of journals that include our voices, xviand some of us are self-declared activists, badgering the systems that exclude us.

Our encounters and collaborations, greetings and words of appreciation are some of the ways in which we validate and encourage each other. These we remember when times are hard, when the writing is too solitary and the path ahead fraught with self-doubt. In short, we need one another and in my formative years, I was inspired by African-American women writers at a time when I needed older women, older role models, to look up to. I first encountered contributor Cheryl Clarke’s work in the anthologies This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, edited by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria E Anzaldúa (Persephone Press, 1981) and Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology, edited by Barbara Smith (Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1983). Reading these collections as I was coming of age felt like walking in from the icy British literature landscape of those times, pushing open a heavy wooden door and entering a warm and welcoming, wood-panelled hall bursting with women of colour engaging in energetic debate, fire roaring, drinks poured, realising that this was a sacred space where we could reveal our truths and realities, not necessarily in agreement or with consensus, but with the right to speak up and out and be heard.

Following the lead of our older American sisters, I was one of several editors of Black Women Talk Poetry (bwt, 1984), an anthology featuring Jackie Kay, who also appears in this anthology and who has since become one of Britain’s leading poets and writers. Likewise, she was one of several editors of Charting the Journey: Writings by Black and Third World Women (Sheba Feminist Publishers, 1988) in which I appeared. Inclusion in these early publications meant a lot. Back then, in the Eighties, British anthologies were peopled by White poets, even the women’s anthologies.

I’ve also known the contributor Kadija Sesay for many years, a tireless literary activist fighting for writers of colour xviiin the uk, long before activism gained currency as a term for political engagement at grassroots and countercultural level. She co-edited, with Courttia Newland, IC3: The Penguin Book of New Black Writing in Britain (Penguin, 2001). Anni Domingo, also an actor, is someone with whom I keep in touch. I recently saw her in a play at the Royal National Theatre. She’s also a novelist, as is Olumide Popoola, who runs lgbtq+ people of colour writing projects. All of these women enrich our Black women’s creative scene in the uk.

Nikki Giovanni is a legendary woman of letters in American literature, a trailblazing poet of the Black Arts Movement who, over fifty years after she published her first poetry collection, is still on fire as a prolific poet and distinguished cultural figure. When I made a bbc Radio documentary on Amiri Baraka in 2015, I had an unforgettable transatlantic phone interview with Giovanni and Sonia Sanchez, who blew my mind with their power, politics and passion.

I remember seeing Staceyann Chin in Russell Simmons’ spoken word production Def Poetry Jam on Broadway in 2002, where she stole the show; I met Ladan Osman at a writing conference in Philadelphia a few years ago, and Tjawangwa Dema at an event in Bristol earlier this year; I’ve seen Gcina Mhlophe perform in London; and Diana Ferrus kindly showed me around Cape Town when I had a British Council Fellowship at the University of the Western Cape in 1999. I met Natalia Molebatsi, the convenor of the poets in this anthology, at the Aké Arts and Book Festival in Nigeria in 2019.

There are also contributors with whom I’ve judged prizes, such as Gabeba Baderoon and Makhosazana Xaba, who is judging the Brunel University International African Poetry Prize for me in 2021, as have Gabeba and Koleka Putuma in the recent past. Winners of the Brunel International African Poetry Prize include the younger generation of poets here: Warsan Shire, our first winner in 2013; Safia Elhillo, a joint xviiiwinner in 2015; Momtaza Mehri, a joint winner in 2018; and Jamila Osman, a joint winner in 2019; while Ngwatilo Mawiyoo and Michelle Angwenyi have been nominated. I’m sure that many of the poets in this collection will also have their own map of networks and relationships and if not yet because they are newly published, then give it a few years and their associations will have proliferated.

Wild Imperfections puts Black women where we know we belong, not at the margins of other people’s art, hovering on the periphery and wondering when we will be invited to join in. Instead, this anthology positions us at the helm of our own creative practice and it defines the nature of the poets’ artistic endeavour on their own terms. Today, African women are claiming space in the poetry landscape like never before.

We can thank social media for the rise in women’s literature enterprises of late. Years ago, we had to go to specialist bookshops to find Black women’s poetry books or we needed to be physically present at readings. Through the platforms of the internet, poets, especially those who are emerging, discover that there is an appetite for their work, before they’ve even published a pamphlet or book.

The poetic voices in this anthology are uncompromising in subject matter and style. They challenge the status quo in so many ways, not necessarily by writing against it, but by writing for us. Poetry by Black women is most likely to be valued first and foremost by us. We are often our most loyal readers, and we have always been the curators of poetry anthologies that gather the scripts of our songs within the book-bound walls of a single volume, a home. We think our work is important enough, and so we make it happen.

Welcome to Wild Imperfections.

EDITOR’S NOTE

This book’s foreword is a demonstration of the honouring of women’s lives and work. Professor Bernardine Evaristo writes passionately about how she knows or where she has crossed paths with many of the contributors. She performs the act of seeing these women/women/womxn and invites you to a gathering that is for and about us. She reminds us that we not only write within and against an anti-Black, misogynistic world but that we use the act of writing for ourselves as a liberatory strategy.

We open with poems that honour different generations of ancestor women who were at the forefront of struggles against racial and gender discrimination. Women like Sarah Baartman (1789–1815) and later Rosa Parks (1913–2005) are honoured by feminist poets who use the intricate language of poetry to pour homage on their memories. Such an opening reflects contemporary feminists’ participation in a culture of revolutionary love as agency. The poems then go on to question and to disrupt the rules of patriarchy and how it continues to translate itself into meaning on and through the lives of women and womxn and womyn. The poems collected here offer teachable moments by answering questions like Who are the Women of Xolobeni? Who was/is Dulcie September? What are dirty/pretty things? What are vulva volcanoes? Who and what are pussy gate-keepers?

Before you get to these questions, you might first ask What is a wild imperfection/perfection? The (im)perfect that I have in mind is a feminist poetic language wrested from the violence of patriarchy and racism; a language that accounts for the body’s trauma and its limitations while reaching beyond for something yet to be formed. Feminist poets use this form of language as transgression against misogyny; a medium xxiithrough which language is used for reclamation of self, for owning all the bits of themselves.

We have gathered poems here that explore how women reclaim a language that is used against them; we take back a language that places us in boxes and tries to make us disappear. This book brings together evidence of this Black feminist poetic language while crafting a lexicon and guide to its depth, dimension and range. This collection is an invitation to spark new conversations and continue existing ones where the poet creates space for ‘wild’ and ‘unruly’ and ‘loose’ and ‘dirty’ ‘witches’ and ‘bitches’ who are perfect in their brokenness and who are no longer seeking permission for their rage, healing and joy. The poems assembled here are about (re)membering what our bodies and their dreams have marked, what they will mark in days to come. They are about honouring the women and the womxn and the womyn who came before us through time, and they will wait, these poems, for another tide of women and womyn and womxn to make new connections across generations and memories. They resist the discourse of ‘fitting in’ to the status quo and therefore (re)define the notion of wild, or what may be deemed perfect or imperfect.

With their words, the contributors of this book are making interventions in a world where patriarchy and racism remain sites of struggle in women’s lives. The poems on these pages are a reflection of spaces that women still have to fight for, starting with the right to own their bodies and their words. Through these poems we make decisions about our lives and the spaces we occupy. These poems speak about birth and death, fertility and infertility, rape and genital mutilation, war, police brutality, exile and forced migration, among other realities. These words also own the audacity to revel in joy, desire and the expression of sexuality, in a world where the bodies of women and womyn and womxn we know or do not know are always turning up dead for being queer, for reclaiming their voices, for leaving abusive relationships or for transgressing respectability politics. xxiiiIn this book we are also holding space for each other’s rage and madness, inherited from a deeply unequal and sexist world.

The contributors give insights on what feminist poets insist on writing about because of what they see in their world. Whatever their theme, each poem is a reflection of the lived realities of most, if not all, women, womyn and womxn, particularly those born Black and poor.

This is an offering and a call to any reader who wants to be part of this conversation through their own interpretation in ways that hopefully open up space for new questions and ideas to flourish. This book is a call to our ancestors – those who see and hear us – that we see, hear and acknowledge the sacrifices they made with their lives, with their bodies, so that we could have a fighting chance for our voices, for our opinions and questions about power – taken every day from women/womyn/womxn and all people who are not White, who are not rich and who are made invisible and disposable every day.

These pages are a gathering of 39 poets from across Africa and its diaspora. Some poets are iconic while others are lesser known, but they hopefully all add to a reference list for poetry lovers and collectors in ways that attempt to satisfy Bibi Bakare-Yusuf’s ideal of ‘the archive of the future’.* This book is also an attempt towards validating women’s cultural production and bringing our collective stories, dreams, memories, desires and ideas to the centre of meaningful socio-political and cultural change.

The process of compiling and editing Wild Imperfections started in mid-2019, while publication was scheduled for early 2020. None of us expected our world to be radically interrupted, least by a global pandemic. Our publication was thus moved up by a year as everyone wrestled with the uncertainties and the trauma of our new reality. In most cases the pandemic amplified Black suffering and meant that poor people would get even poorer and would have even leaner access to basic xxivneeds and resources. In some instances, the global lockdown gave us a blessing (albeit in disguise) to reformat our lives, and to take a slower and more reflective gaze at our work. I had the opportunity to relook the manuscript and while initially the book would have 29 contributors, the call was reopened and 10 more poets responded to the call. Although initial submissions did not feature writing on the impact of Covid-19, the poets who joined us during the Covid-19 crisis submitted poems that spoke to and about the pandemic in ways that only a poet can. Poets like M NourbeSe Philip and Jumoke Verissimo give form and shape to the embodied narratives of Black women and womyn and womxn from across the world on the pandemic and how it landed on the lives and livelihoods of Black and subjugated people.

As stories have done before and will do in the future, it is my belief that these poems, and their message, will outlive us.

It is my hope too that these poems touch you differently, more gently, softer, in a world ‘of endless hardness’.† Once again, welcome to the land of Wild Imperfections.

Natalia Molebatsi

December 2019, San Bernadino, California/May 2021,

Auckland Park, Johannesburg

* Bibi Bakare-Yusuf, Archival Fever keynote address, Abantu Book Festival, Soweto, South Africa. December 30, 2018.

† See Popoola (p90)

DIANA FERRUS

I’ve Come to Take You Home

I’ve come to take you home.

Remember the veld?

The lush green grass beneath the big oak trees

the air is cool there and the sun does not burn.

I have made your bed at the foot of the hill,

your blankets are covered in buchu and mint,

the proteas stand in yellow and white

and the water in the stream chuckle sing-songs

as it hobbles along over little stones.

I have come to wrench you away –

away from the poking eyes

of the man-made monster

who lives in the dark

with his clutches of imperialism

who dissects your body bit by bit

who likens your soul to that of Satan

and declares himself the ultimate god!

I have come to soothe your heavy heart

I offer my bosom to your weary soul

I will cover your face with the palms of my hands

I will run my lips over lines in your neck

I will feast my eyes on the beauty of you

and I will sing for you

for I have come to bring you peace. 2

I have come to take you home

where the ancient mountains shout your name.

I have made your bed at the foot of the hill,

your blankets are covered in buchu and mint,

the proteas stand in yellow and white –

I have come to take you home

where I will sing for you

for you have brought me peace.

3

My Mother Was a Storm

My mother was a storm

a sky filled with dark clouds

she could threaten

or just burst open

she gave warnings

before she lashed

her thundering tongue

uprooting old, dead trees, theories

my mother cleaned with an iron duster

she swept away all dirt and falsehoods

my mother risked having her name tarnished

but could not be tamed

I did not want to see her rain down so freely

she had to stop before it became too wet

I feared her drowning, I feared those floods

that made me gasp for air …

I thought my mother was too intense a winter

knew that she carried a summer

but one in which flash floods hid

oh but how I long for that storm now

a fierce, an all-encompassing one

these days in which hard rocks bash

tear at skin and soul

I wish my mother could enter the sky

and with an angry wind gather the clouds

rain down hard and dissolve

those rocks still so intact, so smug

today I need my mother!

4

This Song of Freedom

this song of freedom

fades, sounds futile

when a lone gunman

loaded with hatred

expels from his chest

unfounded fear onto people

who have never hated him

never demanded from him

anything

but their dignity

NIKKI GIOVANNI

The Seamstress of Montgomery

For Rosa Parks (4 February 1913–24 October 2005)

The saddest thing about your death

Is that you missed your funeral

You didn’t get to see all the people

Who despised everything you stood for

Have to bend one knee to you

having killed no one

having no weapon other than truth

having made no vows other than to your God

To say ‘Well done’

History may well show you

Did not need Martin Luther King Jr so much

As he needed you

Only 29 others occupied the place where the nation

Mourns

Military men, political men, police men

And you seamstress of Montgomery

You were the spark

The flame

The answer

When you sat down

When you kept your seat

When you calmly gave permission6

For your arrest

You opened a window

That had been closed an Eternity ago

By a kiss

When you called upon

That quiet strength

When you leaned on

Those Everlasting Arms

The world creaked to a stop

for a brief moment while you inhaled

while you caught your breath

And blew it on the spine of our people

And we would stand up by sitting down

And we would sit down to stand up

And we would kneel in

And pray in

And teach in

And sing in

And vote in

A new day

Thank you, Rosa Parks

Rest well Mother Parks

Rest well in the Bosom

Of Abraham

Nikki Giovanni

7