Women in Policing E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The history of policing in Britain is a considerably under-researched subject, and the advancement of women within that history even more so. This book seeks to fill that gap, by tracking the progress of women in policing - a story that is longer and more complex than perhaps first meets the eye. Rather than taking a broad narrative overview of women's progress in the realm of law enforcement, this book examines individual experiences within that history. It tells women's stories as a representative snapshot of the time in which they policed, allowing the reader to understand the wider context whilst taking the time to relfect on those women who have made the ultimate sacrifice in the line of duty. Assembled from a collection of experts in the field of police history and the Police History Society, this is a must-read for anyone with an interest in women's, social, or policing history in Britain.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 460

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Tom Andrews, 2024

The right of Tom Andrews to be identified as the Editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 250 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

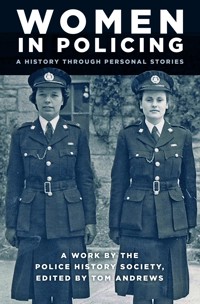

Front cover image: Winnifred Hooper and Eileen Normington, c.1945 (Courtesy of Eileen Normington).

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

TOM ANDREWS (EDITOR)

Tom Andrews is a lecturer in policing at the University of Derby, teaching new police officers on the Police Constable Degree Apprentice (PCDA) programme. He has been lecturing for two years, before which he was a uniformed police sergeant working on emergency response in Nottingham for thirteen years. During this time he researched and co-authored a history of women in policing within that force. He is the editor of the annual Journal of the Police History Society since 2020 and has published two books: The Greatest Policeman? A Biography of Capt. Athelstan Popkess CBE, OStJ: Chief Constable of Nottingham City Police 1930–1959 and The Sharpe End: Murder, Violence and Knife Crime on Nottingham’s Thin Blue Line. He has also published articles in various academic journals.

PETER FINNIMORE

Peter was a Metropolitan Police officer for thirty years, serving in many roles and reaching the rank of superintendent. After retirement in 1999 he continued to be a lead HMIC staff officer as a civil servant for another eight years. Twice winner of the Queen’s Police Gold Medal Essay Competition, he gained a first-class honours degree in History as a Bramshill scholar. In retirement he has had several voluntary jobs, including chairing the Independent Monitoring Board at the Dover Immigration Removal Centre. His main interests are backgammon, reading and trying to keep fit. He lives in Lympne, Kent. He first learned about Margaret Damer Dawson from her grave and memorial in Lympne churchyard.

DEREK OAKENSEN

Dr Derek Oakensen is an independent historian whose research interests are largely focused on local government and criminal justice in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Sussex. An earlier paper, Antipathy to Ambivalence: politics and women police in Sussex, 1915–45, was published in Sussex Archaeological Collections in 2015.

DR DAVID M. SMALE

Dr David M. Smale served in the Royal Marines and as a constable in Lothian and Borders Police, working in both the City of Edinburgh and in the rural Scottish Borders. He studied with the Open University and at the University of Edinburgh and worked as a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Edinburgh. He has contributed chapters to books and written articles in academic journals and in popular history magazines. He is presently researching various aspects of the history of policing in Scotland.

JOAN LOCK

Joan Lock’s first book, Lady Policeman, described her six years’ service in the Metropolitan Police during the 1950s. Her second, Reluctant Nightingale, told of her previous training as nurse. In 1979, she wrote the first history of the British women police – The British Policewoman: Her Story. Since then, she has been a regular contributor to the Police Press and Crime Writers Association magazine, written radio plays and documentaries featuring women police, as well as several non-fiction books and novels on Scotland Yard’s first detectives.

Joan’s late husband Bob served thirty years in the Metropolitan Police as did her brother, Eric Greenslade, in the Cumbria Constabulary, finally as Detective Chief Superintendent.

EDWARD SMITH

Edward Smith is curatorial assistant of the Metropolitan Police Museum at Marlowe House in Sidcup. He assisted in mounting its 2019 West Brompton exhibition to mark the centenary of female officers in the Metropolitan Police, and in 2020 wrote the first entry on Sofia Stanley in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

LISA COX-DAVIES

Lisa Cox-Davies is a former police officer and is now a doctoral student at the University of Worcester. Her research examines the roles and experiences of women in the police forces of the West Midlands area between 1939 and 1990, with a focus on the period of the Second World War and the impact of the Sex Discrimination legislation of the 1970s.

MARK ROTHWELL

Mark Rothwell is a Dartmoor-based author, biographer and historian who has written several books on the history of policing in Devon and Cornwall including Policing the West Country. His areas of interest include police deaths in service, the Great War, the history of women constables, airports constabularies and police transportation. His work as a co-author includes a contribution to the charitable work UK Police Roll of Remembrance published by the Police Roll of Honour Trust.

VALERIE REDSHAW

Valerie worked in the Metropolitan Police before emigrating in 1962 to continue policing in New Zealand. After marriage she resigned to have a family. In 1984 she re-joined the New Zealand Police as an education officer with responsibility for training police recruits, youth aid and senior officers as well as designing the curriculum for all police training. She has represented the New Zealand Police on many public sector bodies including the Equal Opportunities Advisory Group, the Public Sector Training Organisation and the Government Committee for Suffrage Centennial Year. Her book Tact and Tenacity – New Zealand Women in Policing represents research she undertook for the fifty-year anniversary of women in policing there. In 1993, Valerie, was awarded the Suffrage Centennial Medal for services to policewomen and in 2007 was made a member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to education. Her most recent publication is a memoir entitled The Things We Keep.

ROB PHILLIPS

Rob Phillips joined Nottinghamshire Police in 2004 and has served in response, neighbourhood and proactive roles. Among his secondary duties, he is an accredited Wildlife Crime Officer. In 2022 he was appointed to the UK Overseas Territories Hurricane Response Cadre which, when activated by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, deploys overseas to provide essential law enforcement relief and aid to those locations affected by natural disaster. He is passionate about promoting policing history and heritage and in 2012 arranged an event to commemorate National Police Memorial Day which was attended by dignitaries from around the county. He has represented his force twice at the Cenotaph Festival of Remembrance in London, accepted the Ministry of Defence Employer Recognition Scheme Award in Silver on behalf of the force, and provides advice and training within the force for ceremonial events.

ADAM PICKIN

Adam Pickin has been a police officer for over six years and is currently based at Bodmin, Cornwall, as a neighbourhood beat manager. He has always had a keen interest in history and studied Classical History at Swansea University. More recently he’s enjoyed reading the history of police forces and saw this as a fantastic opportunity to research some of history’s most influential and important figures.

KATE HALPIN QPM

Kate is a retired Metropolitan Police officer. She had a varied career serving primarily in investigative roles across South East London and a number of specialist departments as well as several international postings. In 1999 she became the first British police woman to be awarded a Fulbright Police Scholarship to examine how the police and partner agencies in Los Angeles approached youth and gang crime. She also undertook a number of secondments with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Jordan, London and Iraq. She was part of the team that led the Met’s celebrations to mark centenary of women joining the Met in 2019. She is the current Vice Chair of the Police History Society. Kate was awarded the Queen’s Police Medal for distinguished service in the 2021 New Year’s Honours.

DR CLIFFORD WILLIAMS

Dr Clifford Williams is a historian and retired police officer. He studied History and Social Anthropology at SOAS, University of London, from 1980 to 1983 (1st Class Honours) and Criminology at the Universities of Cambridge and Bradford (where he completed his doctorate). After working as a researcher for the Home Office, Clifford served twenty-five years as a police officer in the Hampshire Constabulary and then a further nine years as a volunteer. He has published books and articles on history and criminology, including A History of Women Policing Hampshire and the Isle of Wight 1915–2016 and 111 Years of Policing Winchester: A History of the Winchester City Police Force 1832–1943. His current research includes the history of policing gay and bisexual men.

ANTHONY RAE

Anthony Rae is a retired Lancashire and Metropolitan Police officer. He began research on the UK Police Roll of Honour following the deaths in 1983 of three friends and colleagues, attempting a sea rescue at Blackpool, when he found no such national records existed. He established the National Police Officers Roll of Honour research project in 1995 and founded the Police Roll of Honour Trust charity in 2000, leaving in 2012 for academic research study. In 2016 he received an MA degree in History from Lancaster University related to aspects of police history and deaths on duty. Publications include several Rolls of Honour and Books of Remembrance for police forces and national memorial charities, and some fifty articles in police periodicals, including Police Review and the Police History Society Journal. He joined the Police History Society member since 1985 and became a committee member in 2011.

MARTIN STALLION

Martin Stallion is a retired reference librarian and a former member of the Metropolitan Police Civil Staff. He was awarded life membership of the Police History Society for his twenty years of service as secretary and in other committee posts. His previous publications include several police history bibliographies, a history of Colchester Borough Police and joint authorship of The British Police: Forces and Chief Officers.

CONTENTS

Foreword

Pauline Clare

Introduction

Tom Andrews

1 Margaret Damer Dawson: the Women Police Volunteers and the Women Police Service

Peter Finnimore

2 Mary Adelaide Hare and the Women Police Volunteers, 1914–15

Derek Oakensen

3 Katherine Scott: the First World War and ‘Women Patrols’ in Hawick

Dr David M. Smale

4 The Very Varied Police Experiences of Miss Dorothy Olivia Georgiana Peto OBE KPM BEM

Joan Lock

5 The Twenty-Three: the Metropolitan Police’s First Intake of Women Police

Edward Smith

6 The Recruitment of Women into the Three Police Forces of Staffordshire, 1919–46

Lisa Cox-Davies

7 A Tale of Two ‘Wapsies’: Eileen Normington and Winifred Hooper (Plymouth City Police)

Mark Rothwell

8 Sophie Alloway: the Establishment of Post-War Policing in Germany

Valerie Redshaw

9 PW Chief Inspector Jessie Green Alexander: Nottingham City Police

Rob Phillips and Tom Andrews

10 Sislin Fay Allen: Britain’s First Black Female Police Officer

Adam Pickin and Tom Andrews

11 DCI Jackie Malton: ‘You either follow the crowd or stand out and do the right thing’

Kate Halpin

12 Chief Constable Sue Fish: Highlighting Misogyny, Menopause, and Misconduct

Tom Andrews

13 A Mostly Unknowable History: Lesbians in Policing

Dr Clifford Williams

14 Women Chief Police Officers of the United Kingdom, 1995–2023

Anthony Rae MA

15 Roll of Honour

Anthony Rae MA

Bibliography

Martin Stallion and Tom Andrews

Endnotes

FOREWORD

PAULINE CLARE

It’s probably safe to assume you have bought this book or are thinking of buying it because you have an interest in policing. I certainly had a great interest in policing during my thirty-six-year career in the Northwest of England. Since coming to the end of my policing career, my exposure to policing has been limited to the media and a significant number of crime novels!

This book has several authors, all of whom are well qualified to research and present their work. The material is offered in an easy-to-read format, so even the busiest of readers will race through this publication. The authors have produced the most complete document available on women in policing.

I felt honoured when asked to write this foreword. My career – spanning the period 1966 to 2002 – saw considerable change, including the merger of women into mainstream policing. As a result, reading this book and writing the foreword both resurrected past memories and gave me new information. I recalled carrying my police issue handbag and the shorter women’s truncheon, and being called out at night to deal with female victims and offenders. Initially I was earning 90% of what my male colleagues earned, and my working hours were shorter. However, when there were no specialist women/children’s statements and enquiries to deal with, I performed beat work like my male colleagues, which I thoroughly enjoyed. It felt like I had a foot in both the policewoman’s specialist role and general policing.

As I reflected on my own career, strong emotions stirred within me. I loved the excitement of dealing with drunks near the Docks in Seaforth, Merseyside. If they were fit to walk, they would invariably run into a nearby pub and then into the male toilets. Undeterred, I would shout out who I was and that I was coming in! I thought about a time when as a constable I refused to cook breakfasts for my male colleagues when the canteen was closed. I wanted to be out patrolling. When I was called to see the superintendent (male) about my behaviour, I felt pleased when my explanation and actions were supported.

I also felt real sadness reading about the women who lost their lives on duty or whilst serving as police officers. I knew several of them and in fact worked with one of them in Kirkby. What a great loss they were to their families and the service, and I’m so delighted they have been recognised in this book.

Like the policewomen in this publication, I saw many developments in the acceptance of women in the service during my career. An incident in the late 1980s therefore made me question this acceptance. Whilst a superintendent, I attended a social event at an RAF establishment. I was in plain clothes and accompanied by my husband. I handed over our invitation card to be read out to the guests and was shocked to hear the announcer say, ‘Superintendent Clare and Mrs Clare.’ What fun I had making it clear he had got that wrong!

I think the happiest and most difficult time in my service was as chief constable. Being the first woman chief constable was like living my life in a goldfish bowl: I was a bit of a novelty to those whose stereotype of a chief constable was very different from myself, and experienced these stereotypes on many occasions. Calling me ‘Sir’ within the service was common, and asking me how I was ‘coping’ happened frequently. However, the most obvious and hurtful example occurred whilst I was in uniform attending a county event. I had introduced myself to a very senior male guest, who first eyed me up and down then – if that wasn’t enough – said, ‘If I’d caught you on my rod, I would have thrown you back!’ I was livid and decided to walk away.

That was some twenty-six years ago. Now, thankfully, there are many more women in senior roles in all aspects of life. It gives me great comfort to see so many women throughout the UK reaching the position of chief constable, demonstrated by the figures in this book.

My new learning came from the sections on misogyny, menopause, misconduct and lesbian police officers. None of these topics were on the policing agenda during my service, though the difficulties around these matters obviously existed. I believe that one of the major issues facing the police service, and indeed many other organisations and companies, is whether the culture that exists is appropriate for what that organisation hopes to achieve. That is why I recommend this book to senior leaders in all organisations. With heightened awareness of the impact these matters have on staff and their performance, leaders can consider whether they need to take action or not.

We are so fortunate that the work of policewomen over many years has been recognised in this valuable historic record. I applaud the bravery and courage of our predecessors who challenged authority during very difficult times in our history. I thoroughly enjoyed my trip down memory lane and hope you draw strength and understanding from your reading.

INTRODUCTION

TOM ANDREWS

I FEEL IT ONLY FITTING to begin with a thank you. Thank you for picking up this book and demonstrating an interest in policing history. Whatever your reasons for being drawn to this volume, it demonstrates some form of at least passing interest in the events of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries that have come to define the state of the British police today. Of course, as with any events in history, getting to the point we are at today has often taken a profound struggle on the part of many who have gone before. In this work we are celebrating the strength and initiative of a select group of women who pioneered the role of women in policing to the point we find ourselves at today, where gender equality within the police service is the best it ever has been:1 a third of forces are led by a female chief and seven forces in 2021 recruited more women than men.2 Things, though, are still far from perfect.

We are also celebrating those women who have played crucial roles in the improvement of the police service as a whole, through their transformative efforts to enable this most visible arm of ‘the state’ to provide the best service it can. We will also be taking time to remember those women who have given their all in the service of protecting the public, giving their very lives in pursuit of the greater societal good.

This book has largely come about at this specific point in time as a result of a national period of celebration. Since 2015, forces across the country have been celebrating centenaries of their first warranted female officers with powers of arrest, all following in the footsteps of Lincolnshire’s and the nation’s first, Edith Smith. The majority of forces have commissioned some form of commemorative booklet, presentation, display, social media tribute or combination of those. They have necessarily been compiled by those with an interest in policing history who have had both the time and inclination to conduct and compile that research. This has presented perhaps a unique window of opportunity to collate that expertise and present some of those tales to a wider audience. Martin Stallion has done an incredible job of drawing these various new and pre-existing sources together to compile an extensive and unique bibliography of works relating solely to women in policing that presents ample opportunity for casual further reading and researchers alike.

We are not only at a perfect time to compile this volume, but as the Police History Society, we are also in perhaps a perfect position. With international membership and comprehensive national coverage of all British police forces – territorial or otherwise – there is perhaps no other organisation or group that could feasibly compile a collection with such a broad range of both subjects and contributors. Our list of authors is a veritable Who’s Who of experts within the discipline of police history. We are extremely privileged to have many of these as members of the Society, and further honoured that some non-members who share our values have also offered to contribute their knowledge to this wider audience. It is particularly humbling and has been self-evident throughout the compilation of this anthology that all those who have contributed have placed the achievements of their subjects above any personal sense of aggrandisement. This is a true testament to the achievements of those women who we are considering through the respect their biographers have come to hold them in.

Several of our featured stories are not unique accounts of the women they describe. Some, such as Margaret Damer Dawson, have had their tales told in a multitude of places and in an array of different styles. The majority of our pioneering women have featured in the aforementioned promotional materials distributed by the various forces. Others crop up in academic works which detail their achievements; whether that be in local or national journals as the subjects of master’s or doctoral theses, or even biographies entirely devoted to them. Many of those whose tales feature herein are even sufficiently well known to have their own (often comprehensive) Wikipedia entries. Others are less renowned, but are no less important for that fact. The aim of this book is to compile these diverse and varied accounts into one single volume, looking at the achievements of a handful of select individuals as well as groups of female officers who combined have made a significant impact on policing. Several of the accounts herein are those of pioneering women whose efforts were crucial to the development and acceptance of women as police officers. Other tales provide more of an insight into experiences of female officers at a specific time in general, but conveyed through the stories of exemplar individuals.

This is by no means intended to be a definitive work on identifying all the women who have played pioneering roles in the development of the police. To complete such a study would require an entire series of volumes and decades of research spanning every conceivable aspect of policing. To highlight some particularly notable omissions, we are not telling the story of Edith Smith – the very first woman with a power of arrest. In many senses she is, in fact, unremarkable when compared to her contemporaries involved in ‘policing’ at the time, despite her claim to fame. She was simply in the right place at the right time. Smith does, however, feature in those stories of her peers Margaret Damer Dawson and Katherine Scott. We are also not relaying the stories of the UK’s first female firearms officers; trained police driver; detective; or PSU (riot) officer. Special mention should be given here, though, to Alison Halford, ultimately Assistant Chief Constable of Merseyside Police, who championed and revolutionised victims’ rights in sexual assault cases, including pioneering rape crisis centres (now sexual assault referral centres) and improving how abused adult and child victims were interviewed. She was not only the first female station commander (at Tottenham Court Road), she was to become the first woman to serve at chief officer rank.3 We are also not covering Karpal Kaur Sandhu, the first female Asian officer, out of respect for the tragic circumstances in which she lost her life and her surviving family.4

Perhaps the most notable omission, by its sheer duration, is that of ‘pre-Peelian’ (before 1829) era women who had roles in law enforcement, which, surprisingly, and perhaps contrary to general consensus, was seemingly more common than might be expected. If we expand our definition of constable to include its etymological meaning of ‘Count de Stable’ (or ‘keeper of the stable’), a traditional title for the monarch’s lieutenant in charge of their castles and therefore by extension the surrounding county, we can find an example of one such influential woman as early as 1191. Nicola de la Haye was constable of Lincoln Castle by hereditary right, undertaking the role herself, and defended it ‘like a man’ during two sieges in 1191 and 1217;5 presumably this comment from Henry III was intended to praise her.

Even if we are limiting our definition to purely the law enforcement role to which it is currently associated, we can find examples far earlier than might be traditionally expected. Some of those known about include a record in the Manorial Roles of Northfield (Worcestershire) where it is recorded that, as early as 1451, one Elizabeth Thichnesse was appointed (parish) constable (albeit a man subsequently offered to undertake her duties);6 or Jane Kitchen, parish constable of Upton, Nottinghamshire, who served in the role throughout 1644 at the height of the Civil War.7 Research by J. Charles Cox finds three similar examples of women being appointed petty constables at around the same time as Kitchen in nearby parishes of Derbyshire: an Elizabeth Hurd of Osmaston in 1649; Elizabeth Taylor of Linton, also in 1649; and Clare Clay of Sinfin and Arleston in 1683, albeit, as with Thichnesse, the justices of Sinfin refused her appointment and insisted the previous constable continue in office ‘till hee present another more fitt person to succeed him’.8 If these records can be found in Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Worcestershire, it can be expected to an almost certainty that similar appointments spanned the length and breadth of the country. Perhaps that is a research proposition for someone to follow up with, possibly supported by the Police History Society? These fascinating snippets of history go to show that while our pioneers have played key roles in developing the role of women as law enforcers in the modern era, they are not the first to have held the title ‘constable’ – by over 700 years!

We can also see women working as police ‘matrons’ or supervisors of female and juvenile prisoners, right through until their appointment as sworn constables and beyond. These were often the wives of constables or gaolers, such as Sarah Batcheldor in Liverpool in the 1820s–30s.9 Women often had an uncredited role in policing too, as the unofficial and unpaid secretaries of rural constables, responsible for the upkeep of police houses, the taking of messages in their husband’s absence, and unable under their spouse’s terms of employment to take on any other occupation.10

That the history of women in policing goes back far beyond 1915 should not serve to detract from modern achievements at all. In fact, conversely it should aggrandise them, showing that women, who for centuries had been considered not ‘fitt’ enough to serve as constables or needed men to do the duty for them, are actually more than men’s equals. It just took several hundred years, and a steady increase in the responsibilities of women in society in general, for more outspoken women to forcibly interject themselves into the visible representation of the state that is its police. It has then taken further courageous individuals over the subsequent century to demonstrate that the abilities of women at least match, and in many cases surpass, those of their male counterparts. The strength of character displayed by all our subjects, perhaps most overwhelmingly by those who have laid down their lives in pursuit of their duty, is a testament not only to all of them, but to all their contemporaries as well.

In compiling this book there is no other real method to the telling of the story than to do so chronologically. To do otherwise would obscure the progressive nature of the advancement of women’s roles in the police. Our timeline spans almost the entire history of women in modern policing, starting with the almost bitter rivalry between several different experiments of women in policing. The Women Patrols, Women Police Service and Women Police Volunteers were all instigated independently by outside organisations with an interest in increasing women’s rights during the First World War. These largely self-appointed ‘guardians of morals’ monitored young British women who were suffering the absence of husbands and partners fighting the war, apparently overly excited by the arrival of young and often terrified soldiers in garrison towns, in what has been colloquially termed ‘khaki-fever’. Indeed, it is no coincidence that the first warranted female officer, Edith Smith, was taken on in Grantham, a large garrison town, as we shall discover in the tale of Margaret Damer Dawson. Only one of these organisations received any kind of official sanction above simple tolerance of their presence; the Women Police Service being contracted by the Home Office to provide security at munitions factories. Three of our initial chapters look at these different organisations and their conflicting opinions on how women should be involved in supporting the war effort. Intriguingly, there is little evidence to support the idea that any of the rival organisations saw a role for women as constables, at least initially. Moreover, it even appears that those involved in their establishment could have, in fact, looked down on the police service itself, seeing their calling as different, and much more akin to social work; as we shall see in the cases of Katherine Scott and Mary Adelaide Hare. Tragically, their tenacity and determination to prove themselves resulted in the premature deaths of several of these early pioneers.

In another, perhaps surprising, throwback to more antiquated times, there is here a further similarity in the use of women to maintain the peace during times of war, when the men were otherwise engaged. Contemporaneous to the aforementioned female petty constables, during the height of the English Civil War, women were called upon to keep a night watch on the town of Nottingham. The Parliamentarian commander of the castle’s garrison, Colonel Hutchinson, had no spare troops to patrol the neighbouring town. Lacking for men:

on one occasion a night watch of fifty women was organised against incendiarists and surprise Royalist attacks – ‘it being considered that fifty women in a state of terror would create an alarm that would arouse those sleeping in their beds more effectually than any other means which might be devised’.11

Their efficacy is not recorded, and the suggestive use of ‘one occasion’ implies this experiment was not repeated. There is clearly a seismic difference in the fundamental belief about the abilities of the women conscripted into replacing the men between this instance and their later widespread use in the First World War. Nonetheless, it demonstrates that even in a period where women were treated more as property than equals, there was recourse to using them to ‘backfill’ in times of crisis in a law-and-order context.

As the book continues, we will see the progression of these self-made roles of the various women’s organisations into pseudo-officialdom, which in turn encouraged recognition of the benefits to the forces of having women among their number. This progression was slow, and in many cases halting, as budgets were cut and the untested female officers were therefore the most expendable. Early government commissions into the role of women in policing following the conclusion of the war were also somewhat sceptical of their value, which further hindered their expansion. Not least among these were the 1922 National Committee on Expenditure cuts, or ‘Geddes Axe’, advocating swingeing cuts to public services following the First World War, under which women police suffered heavily, seeing a reduction from 112 to just twenty-four.12 This was in spite of mostly favourable evidence of their abilities heard at the Committee on Employment of Women on Police Duties, or ‘Baird Committee’,13 and evidence heard in Parliament as regards their efficacy.14 Edward Smith covers this in his chapter ‘The Twenty-Three’, looking at the first female recruits into the Metropolitan Police Women Patrols. Lisa Cox-Davies carries on this theme by highlighting the differences in the acceptance of women police by examining the experience in three different Staffordshire forces.

Once begun, however, some things are hard to stop, and there can be no doubt that these early pioneers would have been standout officers, driven by a desire to prove their worth and value. The benefits of allowing women to assist with police work – even if it was only one or two per force in some cases, and then to only deal with women or children – had been demonstrated. Annual reports from the Chief Constable of Nottingham City Police, an early adopter of three policewomen in 1919, state: ‘[the policewomen] are proving very useful and with added experience their work and sphere of usefulness will be enlarged’. That was compounded the following year with the statement: ‘The policewomen employed continue to do most useful work’.15 This seems very much in line with the views of some fifty other chief constables of the time giving evidence to the Baird Committee.16 The sheer fortitude of some of the early senior officers, such as Sofia Stanley and Dorothy Peto, whose tales herein follow those of the unofficial wartime pioneers, ensured their survival against some tall odds.

Women’s position within the police was tentative at best throughout the interwar years, and numbers still significantly limited. As with so many things, the Second World War was to change that forever. The need to once again call up significant numbers of men to arms, as well as the need for increased Home Guard in the face of invasion and air raids, meant that every available hand was required. The government once again turned to the extensive pool of largely untapped resources that women represented, and women’s reserve organisations sprang up in various branches of the military and civilian services. The police were no exception, and the Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps (WAPC) was born, the Home Office allowing up to 10 per cent of a force’s strength to now be the auxiliary women.17 Mark Rothwell illustrates the trials and tribulations faced by those women who joined the blue by looking specifically at the experiences of two incredibly brave Plymouth WAPC officers.

It is perhaps telling of the still prevailing attitude towards women in society that many chief constables were against the introduction or use of WAPC officers, in spite of increased responsibilities and loss of staff to the military. Nottingham City Police’s Chief Constable of the time, Capt. Athelstan Popkess, established air-raid precautions and planning that were hailed as exemplary and a template the rest of the country followed. He had sophisticated underground control centres co-ordinating police, fire, ambulance and local government responses to any bombings or invasion, and divisional substations to relay orders or casualty information.18 In spite of this, he was adamantly opposed to taking on any WAPC personnel, despite them potentially being volunteers and therefore not incurring him any expense. His force even had a handful of female officers at that time, unlike many others. He wrote to the Home Office at the outbreak of war on 1 September 1939: ‘I do not think there is any need for such a body being formed in this city, and I do not wish to bring the matter before the Watch Committee.’ Cox-Davies definitively shows that this was far from a unique standpoint.

Popkess was not above admitting his error, though, perhaps in light of the valuable contribution the WAPC officers had made nationally, and in November 1941 the first WAPC officers joined the force.19 The high number of military casualties from police forces, coupled with the demonstration of their abilities by the WAPC officers, meant that significant numbers from that reserve were retained by forces as full-time sworn officers after the war ended. Interestingly, however, members of the WAPC were not sworn police officers and lacked a power of arrest; and in fact, memorandums of understanding from the Home Office outlining the terms of service of WAPC recruits explicitly stated: ‘Members of the Corps will not be Special Constables’.20

The abilities of women to work well in the police had been proven during the Second World War, thanks in large part to the efforts of the oft-forgotten WAPC. Others who had been lucky enough to have been one of the very few sworn officers during that time had been able to exemplify the same fortitude shown by their forebears. In the case of Sophie Alloway, her abilities meant she was posted to Germany to help rebuild the country post-war and establish the women police there – very successfully, reaching high rank and significant respect at the same time. It is Valerie Redshaw’s privilege to tell her story.

As a result of their proven abilities, even in the face of significant, often prejudiced opposition, forces began to open their doors far more readily to female applicants and numbers increased significantly in the decade following VE Day. They were still limited by the Home Office, though, to comprising no more than 10 per cent of a force’s strength, and existed as a separate entity – the Women Police. They were paid only 90 per cent of the salary of their male counterparts (and were accordingly referred to as the ‘ninety percenters’), but did not work night shifts. They were also not allocated specific beat duties, often being supernumerary to shifts and used for additional visibility presence, as bait in sting operations or to replace crossing patrol officers who were off on leave or sick.21 For the most part they were expected to still deal only with offences involving women and children, and for this they could often be summoned from their homes overnight if such an incident occurred when no Women Police were on duty.

Throughout this time female officers were also implicitly barred from marriage, having to either chose a life of devotion to duty akin to a nun or being forced to leave the service if they found a man with whom they wished to start a family. This was not just local policy or practice, but formed part of the national Police Regulations. This has led to some speculation that many of the women who served a full thirty-year career were lesbians, in a time when coming out as such was unimaginable. Clifford Williams touches on this idea in his chapter exploring the history of lesbian officers.

In 1946, the Home Secretary, Chuter Ede, amended the forced resignation on marriage policy, even stating at a Ryton-On-Dunsmore training school passing-out parade that retaining married women might be beneficial in gaining the respect of younger girls with whom the police would interact:

They have to give advice and help to young girls and on occasion I think it is more likely to be received with respect from a married woman than one who is single. A young girl is apt to think that all women are single after about nineteen merely because they have never had any ‘fun’. The fact that a lady has been able to get a husband does entitle her to some respect in the eyes of that particular section of the community.22

Clearly there was some thought behind the policy alteration, about the improved community relations the action might foster, even if the prevailing misogynistic sentiment of the time is all too evident.

At the same time, recruitment adverts for women to join the police laid bare the expectations of what the Metropolitan Police were looking for in the 1930s, when they declared ‘Hefty girls wanted’ who could ‘withstand a rough and tumble’. It went on to stipulate that ‘they must never marry – or their career will end’, and that the ideal candidates were ‘spinsters and widows, girls in universities and public schools, and girls with training in nursing and social work’, who ‘must be at least five feet four inches high’. Such an advert would be anathema to any recruitment campaign today and is clearly awful in its tone by modern standards, but it provides an excellent time-capsule to demonstrate half a century’s progress.

Thankfully, the easing of the restrictions around forced severance on marriage was the start of a slope towards acceptance, and it is around this time that we see Women Police officers achieving not only high ranks in provincial forces outside of the Metropolitan Police, but also respect from their male colleagues. It falls to Rob Phillips and Tom Andrews to give an account of female officers smashing these proverbial glass ceilings with the highest-ranking officer in Nottingham City Police, Jessie Alexander, who reached the position of Police Woman Chief Inspector.

The 1975 Sex Discrimination Act finally saw an end to the separation of the Women’s Branch from the (Men’s) Police and the theoretical abolishing the title of ‘WPC’ – even if not in popular parlance for several more decades. This was not the end of the fight for equality, though, nor thankfully of the progress towards it. Sue Fish, later to be Chief Constable of Nottinghamshire, recalls that when she started as late on as 1986, only 8 per cent, or 176 officers, of the total strength of that force was to be women, whichever was the fewer, and no more than two women were to be on each shift. The force were seemingly allowed to get away with this flagrant breach of the law both because it enforced the law, and because this policy wasn’t physically written down anywhere, and thus not ‘official’. Female officers were still issued truncheons half the size of their male counterparts, specifically designed to fit in their uniform-issued handbags.

Thankfully, as women formed an increasing percentage of the police workforce, they also had more influence over the policies and practices of the police. Victims of sexual offences had traditionally had a very difficult time with the predominantly male police force, either in having their reports believed, through some misguided sense that the victim had brought their predicament on themselves by dressing provocatively, in what would now be termed ‘victim-blaming’, or by the invasive and gratuitous nature of the evidence gathering and questioning they were subjected to by the male officers. The attitudes of the detectives towards victims of the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’ and ‘Sussex Strangler’, that somehow because they were sex workers they were less deserving of the police’s time and more at fault for bringing the offenders’ actions on to themselves, is exemplary of this period. Thankfully, as female officers took up more positions of responsibility they were able to drive through wholesale changes in the way victims were dealt with, making the reporting of sexual offences far less of an ordeal and almost second victimisation than it had been before.

Finally, on our chronological journey we hear from Tom Andrews, who charts the career of Sue Fish, not the first female Chief Constable, but possibly the first who stood at the helm of the force in which she spent the majority of her career. A woman who beat the gender-biased odds of a typically male-dominated aspect of law enforcement to become the Association of Chief Police Officers’ lead on armed policing. She was instrumental in further enhancing the rights of women both within and without the police service, responsible for overseeing the introduction of the country’s first menopause policy within a police force, and introducing the idea of misogyny as a hate crime category. The latter proved prescient when it was to come to the fore some five years later with the rape and murder of Sarah Everard, a woman walking alone at night across London’s Clapham Common. This tragic incident – conducted by a (male) police officer, no less – prompted a wave of demonstrations across the country in favour of increased protections for women and increased awareness of societal misogyny.

Sue’s work crucially took place alongside the steady increase of female officers in the police, which studies have shown has a positive impact on the public’s perception of the police (legitimacy). This comes as result of a marked reduction in use of force by and against female officers, as well as them receiving fewer complaints and instituting organisational change – as epitomised by Sue Fish.23 This serves to cement the impact all these pioneers have had in transforming policing for the better throughout the preceding century.

We conclude with chapters examining more specific histories within this broader historiography. Clifford Williams looks at the fight for the rights of the lesbian communities within the police service. The struggle of people to be recognised for who they are and whom they can love has taken place simultaneously with the fight for equality of women, and spans a concurrent timespan; albeit taking place far more in the shadows until comparatively recently.

Tony Rae concludes our journey with a reflection on all the women in policing who have made the ultimate sacrifice in service of the public. Thankfully, the number of women who have given their lives in the line of duty is relatively small, but their sacrifice is by no means any less significant for that. The names of female officers who have been murdered on duty are evocative of some of the most high-profile incidents in policing: Yvonne Fletcher, gunned down in the street by diplomats she was sworn to protect, for whom the hunt for justice has taken in excess of thirty-five years and in whose memory the Police Memorial Trust was founded; Sharon Beshenivsky, shot and killed by armed robbers; Fiona Bone and Nicola Hughes, killed in a brutal ambush involving grenades and a gun by an offender who called in a hoax burglary report. All went to work expecting to return to their families and loved ones, but experienced brutal, fatal violence, simply because of the job they chose to perform.

This book looks to serve as a monument to these and every woman’s dedication, stubbornness, beliefs and in many cases self-sacrifice to further their cause and that of every woman in policing from the First World War until today. Every female officer serving today and tomorrow in His Majesty’s Constabulary owes their position to the hard-won rights of these forebears and their peers. Every female officer today is their legacy. This hopefully serves as their story. In words etched onto the gravestone of Lilian Wyles BEM by the Metropolitan Police Women’s Association: ‘We stand upon the shoulders of such pioneers.’

1

MARGARET DAMER DAWSON

THE WOMEN POLICE VOLUNTEERS AND THE WOMEN POLICE SERVICE

PETER FINNIMORE

Margaret Damer Dawson in her Women Police Service uniform.

THESE DAYS ONLY THE MOST extreme anti-feminist would deny that policing was a suitable job for a woman. Before the First World War, however, when women (and especially married women) were barred from so many occupations, it would have been considered the ludicrous proposition of a few extreme feminists. It has been suggested that Margaret Damer Dawson, founder of the Women Police Service (WPS) in 1915, ‘began the process of normalising women in the police force, disproving many of the prejudices of the male policing establishment’.1 In fact, after the war, progress towards overcoming those prejudices was, like many other facets of women’s equality, painfully slow until the 1970s. Some would say it is still slow. Margaret Damer Dawson was certainly one of the key figures among those who created and led women police organisations during the war. But did she advance or retard the development of women policing? Or was her Women Police Service an irrelevance? Could she have contributed more to policing if she had not died suddenly of a heart attack in May 1920?

The context within which she was operating included: a male-dominated society and campaigns, notably the suffrage movement, to promote women’s equality; the treatment of women within a criminal justice system run by men; the key role of charities run by middle-class philanthropists in caring for and controlling those in ‘moral danger’, usually women or children, or who were a ‘moral danger’ to others; and, of course, the social, political and economic upheaval caused by war.

The women’s suffrage movement had gathered momentum in the nineteenth century and became increasingly militant after the founding of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. With the declaration of war against Germany in August 1914, Suffragette leaders called for an end to militancy for the duration of the conflict. They believed that by supporting the authorities in a national emergency they could win support for women’s equality.

Margaret herself had been active in the National Vigilance Association and the Criminal Law Amendment Committee, two bodies that had campaigned for action against white slavery and to promote what was described as ‘social purity’. An undercurrent in these campaigns was that the male-dominated criminal justice system was unlikely to tackle these issues effectively until women were represented in key roles such as magistrates and women police. Little progress had been made in these areas, however, before 1914.

For young women, the war brought new freedoms and opportunities for work outside the home, in industry and agriculture and even abroad as nurses and ancillary workers. This enormous social change brought fresh concerns about the ‘moral welfare’ of young working-class women. In the autumn of 1914 especially, there was growing fear of an epidemic of so-called ‘khaki fever’. In Parliament and the press concern, and in some cases moral panic, was spreading. Young women, it was believed, excited by the arrival of soldiers in camps near towns and cities, were behaving dangerously, ‘drinking alcohol, running after men in uniform and behaving immodestly’.2 In the House of Lords there was a call for legislation to allow the arrest of ‘women of notorious bad character who were infesting the neighbourhood of … military camps’.3 Although the moral panic was probably disproportionate to reality, it has been estimated that over 6,000 women became involved in various forms of policing during the First World War as a result, often with the aim of promoting ‘moral welfare’ or ‘social purity’.4 Much of this work was more like voluntary social work than policing. The WPS was one of the most prominent women’s policing bodies, largely due to the leadership and organisational skills of Margaret Damer Dawson.

The structure, organisation, efficiency and morale of British policing before and during the war is another important element of the context. Between 1910 and 1920 there were over 180 separate police forces in England and Wales, with little central guidance from the Home Office until the outbreak of the war forced some co-ordination. Discontent among police officers was widespread over issues such as the right to confer (i.e. to form a trade union); pay that was less than that of an agricultural labourer, a third that of a munitions worker, and which was not keeping up with wartime inflation; the loss of the recently introduced weekly rest day, meaning they worked seven days a week with no paid overtime; and they were forbidden from resigning during the war!5 However, in her detailed account of the founding and work of the WPS, Margaret’s partner and WPS ‘Sub-Commandant’, Mary Sophia Allen, makes no mention of the poor state of policing that was to lead to the 1918 and 1919 police strikes and the great improvements thereafter. This omission suggests the pair were far more concerned about setting up a separate women’s force, than about the problems of the existing men’s force.

MARGARET’S EARLY LIFE

Margaret was born in Sussex on 12 June 1873, the daughter of Richard Dawson, a surgeon who died in 1891. Her mother remarried in 1914 into a wealthy aristocratic family, becoming Lady Agnes Walsingham, wife of Thomas de Grey, 6th Baron Walsingham. Most of what is known about her early life is drawn from the memoirs of her friend and partner, Mary Sophia Allen.6 We are told that she was educated privately and gained the Royal Academy of Music Diploma and Gold Medal. ‘She had remarkably diverse and contradictory gifts, was keenly interested in sport … all the arts’ and was ‘an experienced alpine climber, an expert motorist, an enthusiastic gardener, [and] a passionate lover of animals’. Her activities included ‘frequent trips abroad’.7

This could only have been the life of a person of independent means, presumably provided by her wealthy family. Another clue to the wealth of her family comes from the census. In 1881, her household in Hove, including two sisters and a brother, also comprised two nurses, a cook, a housekeeper and a housemaid. The 1891 census lists six servants. Although Margaret’s father had died in 1891, the family was still well off. While little is known about her sources of income, at the outbreak of war she owned two substantial properties: 10 Cheyne Row in Chelsea, and Danehill, a large house set in 2 acres in Lympne, near Hythe, Kent.

In 1901, Margaret was staying in Balcombe House, a grand estate near the village of Balcombe, Sussex, the home of the Delius family, with an even larger army of staff and servants. She was an accomplished pianist and had become a close friend of Berthe Delius (a cousin of the composer Frederick Delius) while studying at the London School of Music. She shared with Berthe a deep interest in animal welfare, an interest that seems to have been her main activity up until 1912. For several years they also shared a luxury apartment in Maida Vale, west London, with Lizzie Lind af Hageby, founder of the Animal Defence and Anti-Vivisection Society (ADAVS).8

In 1906, she was Organising Secretary of the Congress of International Animal Protection Societies. She accompanied Lizzie Lind af Hageby on a lecture tour in the USA in 1909 and they organised an international conference in London for over 850 delegates. As Honorary Secretary of the International Anti-Vivisection Council, she toured Europe to gather evidence of what she believed to be the cruel treatment of animals in medical research and farming; and she wrote passionately, urging public awakening from the ‘lethargy of indifference and ignorance … [to] escape the net of medical tyranny which is slowly but surely being thrown over us’.9 For her animal welfare work she was honoured by Danish and Finnish animal protection societies. She resigned from her ADAVS post in November 1912 to focus on other philanthropic work. Her deeply held convictions about animal rights were certainly extreme, especially her certainty that diseases were spread not by germ carriers but by other environmental causes. The vivisection of animals for medical research was therefore not only cruel, it was unnecessary. She had demonstrated organisational ability and dynamic leadership that would be crucial in establishment of the Women Police Service.

THE WOMEN POLICE VOLUNTEERS

In the months after the declaration of war, the transition to a war economy and the disruption to society was swift. By October 1914, the National Union of Women Workers (NUWW) had begun organising local Women Patrols, prompted by the many army camps rapidly set up near towns and cities throughout the country and concern about the moral welfare of young women. Other local groups also set up voluntary women’s patrols. They were, however, seen as a temporary wartime initiative, with non-uniformed volunteers giving up a few hours a week and not connected to existing police forces. As the national NUWW patrols organiser wrote to The Times, ‘The voluntary patrols are neither police nor rescue workers, but true friends of the girls’.10