Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Fox Chapel Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

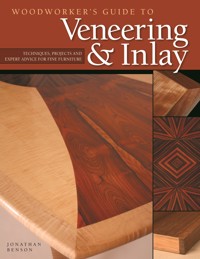

With this complete resource from professional furniture-maker and veneer specialist, Jonathan Benson, you'll learn how to inexpensively recreate the beauty of exotic wood with veneer and in-lays. Now, woodworkers of any skill level can master the classic technique of recreating the beauty of exotic wood. Included is a complete overview of the entire veneering and in-lay process along with step-by-step exercises that culminate in four beautiful pieces: a dining room table, a wall mirror with shelf, a marquetry picture, and a parquetry design.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 280

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2007

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WOODWORKER’S GUIDE TO

Veneering& Inlay

WOODWORKER’S GUIDE TO

Veneering& Inlay

JONATHAN BENSON

© 2008 by Jonathan Benson and Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc., East Petersburg, PA.

Woodworker’s Guide to Veneering and Inlay is an original work, first published in 2008 by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

Print ISBN 978-1-60765-903-7eISBN: 978-1-60765-903-7

Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Benson, Jonathan.

Woodworker’s guide to veneering & inlay / Jonathan Benson. -- East Petersburg, PA : Fox Chapel Publishing, c2008.

p. ; cm.

ISBN: 978-1-56523-346-1

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Veneers and veneering. 2. Marquetry. 3.Woodwork. I. Title. II. Title: Veneering and inlay.

TS870 .B46 2008

674/.833--dc22

0711

To learn more about the other great books from

Fox Chapel Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free 800-457-9112 or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

Dedication

To Sherry

Acknowledgments

During the past three decades, I have been lucky enough to work at a craft I love, to continue to explore new ideas in the studio, and to then pass on that knowledge. I want to thank the many students I have had for their thoughtful questions and new insights, which have taught me so much. I would also like to thank my clients for giving me the freedom to push the boundaries of my work and move it into new areas. Finally, I would like to thank Sherry, my wife, for her love and support during the past 20 years.

This book would not have been possible without John Kelsey’s thoughtful editing and extensive knowledge about the woodworking field. I would also like to thank those who contributed material for the production of this book, including Silas Kopf, Northhampton, Massachusetts; Frank Pollaro, Pollaro Custom Furniture Inc., Union, New Jersey; Dave Bilger, B&B Rare Woods; Michael Erath, Erath Veneers; Dave Boykin, Boykin Pearce Associates, Denver, Colorado; Mike Bray, Berkeley, California; and Woodwork Magazine.

—Jonathan Benson, West Des Moines, Iowa, April 2007

Contents

Chapter 1:Veneering Then & Now

Chapter 2:From Forest to Shop

Chapter 3:Cutting, Matching & Taping Veneers

Chapter 4:Substrates

Chapter 5:Adhesives

Chapter 6:Pressure & Presses

Chapter 7:The Edge

Chapter 8:Problems, Repairs & Finishing

Chapter 9:Complex Matching, Inlays & Borders

Chapter 10:Marquetry & Parquetry

Chapter 11:Band-Sawing Veneers

Chapter 12:Mirror Frame

Appendix 1:Glossary

Appendix 2:Index

Appendix 3:Veneering Suppliers

CHAPTER 1

Veneering Then & Now

A wood veneer is an attractive but thin slice of wood that can be glued onto a furniture surface or wall panel, creating a rich look for very little expenditure of expensive material. Veneering is an old process that has changed and developed along with advances in wood processing and cutting. Historically, veneer was used to decorate the very finest furniture; in recent times, it has also been used to disguise some of the worst. Today, it is still possible to produce very fine veneered furniture using basic woodworking tools.

Desert Sun Sideboard by Jonathan Benson combines vintage Brazilian rosewood, curly maple, and ebony veneers. The 36" x 62" x 22" sideboard was created using the simple tools and techniques covered in this book.

Historical background

Veneers have been used in woodworking for more than 5,500 years. Examples of veneered pieces dating back to at least 3500 BC have been discovered in the pyramids of ancient Egypt. Hieroglyphics and frescoes created around 1950 BC depict workers cutting, joining, and gluing down sheets of veneer using stones as weights for clamping. The veneers were cut with an adze, a tool resembling an ax with its blade turned perpendicular to the handle. This process produced veneers that were rough, uneven, and about ¼" thick.

As technology progressed, it became possible to make thinner veneers. In Roman times, an iron-bladed pit saw was used. One worker stood in a pit below a log while another worker stood above, each pulling opposite ends of a large saw. The Romans also developed smaller bow-type saws, which could be used by one or two people. Sawn veneers could be much thinner than adzed veneers, close to ⅛" thick. Like adzed veneers, these early sawn veneers remained uneven and required much leveling and smoothing to create an even surface. Because these processes were labor intensive, veneers could only be used in the highest applications.

Figure 1-1. A 48" x 22" x 12" Art Deco chiffonier in curly maple is a classic 1930s Ruhlmann reproduction by Pollaro Custom Furniture Inc., Union, New Jersey. (Photo courtesy Frank Pollaro.)

Figure 1-2. A wet bar wall, made with quilted makoré panels and cabinets, pomele sapele bent-laminated doors, and a granite counter top, was designed by Dave Boykin and made by the three-man shop of Boykin-Pearce Associates, Denver, Colorado. (Photo courtesy Dave Boykin.)

Just like craftsmen today, early craftsmen had good reason to go to such trouble to fabricate veneers. In ancient Egypt, fine woods of interesting and contrasting figure had to be transported great distances, making them scarce. Cutting the wood into thin layers enabled it to cover more surface area. Also, rare and highly prized burls, large knotty growths found in many species of woods, will check, crack, and warp unless sawn very thin (Figure 1-3). Additionally, thin woods can be arranged and combined in intricate patterns, regardless of grain direction or species, without problems due to wood movement (see Chapter 2).

When circular saws came into use during the Industrial Revolution, veneers of 1⁄16" could be produced in large quantities. Veneer began to be used on a much greater scale. More people than ever before could own these inexpensive, mass-produced goods. Unfortunately, at this same time, veneer came to be associated with cheap, shoddy construction. The idea of a fine veneer covering over a cheap interior has been associated with the process ever since. Dictionaries today define veneer as “to disguise with superficial polish” or a “false show of charm” (Webster’s Dictionary, New Edition).

Figure 1-3.Ziggurat Chest of Drawers, 60" x 24" x 18", by furniture artist Silas Kopf of Northhampton, Massachusetts, features burl veneers with mother-of-pearl inlay banding. (Photo courtesy Silas Kopf.)

The middle class grew tremendously as labor shifted from working the land to working in factories. Technology continued to advance and veneer became ever thinner. With the incorporation of the mechanized knife in the early 20th century, veneer could be sliced to ⅓2" or less. (Today, most U.S. veneer is 1⁄28".) This was a huge advance in the efficient use of woods. The veneer was cut thinner, allowing it to cover more surface area, and the saw kerf (waste from the thickness of the saw blade itself) was eliminated. Far more veneer with a matching pattern could be produced, allowing for the coverage of larger areas, including entire rooms (Figure 1-2), with the same uniform pattern.

Then, due to the popularity of exotic woods during the first half of the 20th century, some of the finest furniture being produced was made using veneers (Figure 1-1). Consequently, during the last 200 years, veneer has lived a dual existence as the best and worst that wood furniture design has to offer. Contemporary furniture artists have again turned to veneer for both the beauty and luxury it offers as well as its economy and practicality (Figure 1-4).

Figure 1-4. A very practical set of three nesting tables by Jonathan Benson combines purpleheart veneer with stained curly maple turnings (20" x 26" x 20"). Although it might have been possible to make the curved side panels in solid wood instead of laminated veneers, the cost would have been prohibitive.

Advantages of veneer

With the rapid rate of deforestation and the near disappearance of an increasing number of tree species, use as veneers may be the only alternative left for many types of woods. Already, many species and rare figure configurations are only available in veneer form (see here). Some exceptionally rare species, such as premium-grade fiddleback makoré, may only appear on the market as one or two large veneer logs every few years.

The yield advantage of using veneer is tremendous. Take a given log and rough-cut 1"-thick boards from it. The lumber, dried and planed on both sides, yields a ¾"-thick board that will cover one square foot of surface area for every board foot of lumber sawn. Take the same log and cut it into 1⁄30" to 1⁄40" veneers, and it will cover 30 to 40 times as much surface area. Considering that, per square foot, the retail price of 1"-thick lumber is often only two or three times the cost of veneer, it is obvious why the best logs go to the veneer mill.

There are also environmental advantages to consider. Less lumber grown in tropical rainforests is needed to cover the same surface area when sawn as veneer. Renewable and waste materials, including recycled industrial waste, can be used as a substrate (see Chapter 4, here). Many companies are starting to use non-toxic, soy-based glues to manufacture particleboard, fiberboard, and plywood, all of which can be used as veneer substrates.

But the visual advantages of veneer may be the most important to designers. Veneers make it possible to combine different woods in an infinite number of ways, regardless of grain direction. That makes them “omni-directional”—both movement across the grain and movement due to differing densities of various species are eliminated once the veneer has been properly glued down to the appropriate substrate. The veneer is just too thin to move in any direction, regardless of seasonal weather changes. The idea can be taken to beautiful extremes, as in the pictures created by marquetry and the geometric patterns of parquetry (see Figure 1-5, for example). In addition to marquetry and parquetry, veneer patterns commonly include book-matching, four-way matching, and radial matching. In book-matching, the leaves of veneer open like a book and the pattern reverses from one leaf to the next. In a four-way match, the book-match occurs both side-by-side and top-to-bottom, like a folded piece of paper. In a radial match, triangles of matched veneer fit together around a common center like a sunburst. More complex patterns are based on the three basic ones.

Figure 1-5. Silas Kopf: Tulips and Bees side table (54" x 20" x 35") combines marquetry in the floral doors and the bees, with parquetry in the assembly of blocks containing the bee motif itself.

Figure 1-6. Treefrog Veneers manufactures a variety of exotic-looking laminate sheets to be used like wood veneers.

Figure 1-7. The curvy base of Jonathan Benson’s W Table is made by bending and gluing fiddledback makoré veneer and combining curly maple elements (17" x 44" x 22").

Figure 1-8. Veneer is flexible and can easily be laminated into curved furniture forms. Constructivist Coffee Table, by Jonathan Benson, includes walnut, cherry, and granite (17" x 44" x 22").

Newer veneer materials, which can help conserve precious tropical lumber, are always coming on the market. They are made from less scarce and sustainable species of wood, as well as from synthetic materials made to look like rare woods. Other products have intricately patterned surfaces that do not resemble wood at all and can be produced in almost any color. Some have a herringbone or other pleasing pattern. The materials can completely change what a wood surface looks like, and are applied in much the same manner as traditional veneers, often combined with other wood veneers and solid wood (Figure 1-6).

Because a sheet of veneer is extremely flexible, all of the patterns, book-matches, and inlays discussed in this book can be applied to curved surfaces (demonstrated by the curved mirror project in Chapter 12). In fact, modern veneer gluing and pressing techniques make it relatively simple to veneer over curved surfaces, as well as to create curved pieces made entirely of veneer (Figures 1-7 and 1-8).

Figure 1-9.Dining Table by Jonathan Benson is made of holly wood and Swiss pearwood veneer, stained and painted wood, and glass (56" x 28").

Figure 1-10.Sideboard by Jonathan Benson is vintage Brazilian rosewood veneer and curly maple with tambour doors (36" x 50" x 18").

Figure 1-11. Jonathan Benson’s Pyramid Pedestal (37" x 15" x 15") has a bubinga base, vintage African satinwood sides, cocobolo and bubinga trim, a granite top, and a light to illuminate the gold-plated capstone made by jewelry artist Matha Benson.

Figure 1-12.Hall Table by Jonathan Benson features fiddleback makoré, curly maple, and glass (32" x 48" x 18").

Figure 1-13.Samovar Wall Shelf, with holly and Swiss pearwood veneers by Jonathan Benson, combines painted and stained woods (36" x 56" x 12").

The ability to properly handle, cut, match, and attach veneers can open up an entirely new range of ideas to woodcrafters of any skill level. At the same time, a lot of wood can be saved by using veneers. Most of the veneering processes covered in this book do not take a huge investment of either shop space or money. A small shop or an individual can go a long way using the basic tools most woodworkers already have. The addition of a screw-type or vacuum-bag veneer press opens up even more possibilities (see Figures 1-9 through 1-16). I will also cover more complex and production-oriented processes for shops that do a lot of veneer work. Anyone with an interest in veneering can start with some of the basic processes and move on to the use of more sophisticated tools and techniques as needed.

Figure 1-14.Sidetable by Jonathan Benson features fiddleback makoré, stained and bleached woods, curly maple, and a glass top. (30" x 30" x 18").

Figure 1-15.Hands of Time tall clock, by Jonathan Benson, is made of purpleheart and curly maple (62" x 26" x 12").

Figure 1-16.Pedestal by Jonathan Benson is made with pomele sapele veneer, maple burl, and a marble top (43" x 15" x 15").

CHAPTER 2

From Forest to Shop

Wood is an organic, dynamic material that continues to react to its environment long after it has been cut, dried, and finished. Knowing how and why woods react to moisture, seasonal changes, and sunlight is essential to creating effective designs that will last for generations.

Wood growth creates the grain patterns and figures seen on solid wood and veneers. Slicing veneers from a log creates the most beautiful wood out of the rarest, most interesting logs, and the process can produce a variety of figure patterns. An understanding of the manufacture of veneer helps the craftsman know what to expect when purchasing the material. Proper storage also is important to keep veneers flat, intact, and ready to use. The veneers shown in Chapter 2 are not enhanced by any wood finish—they are all raw wood, not sanded or finished.

Beautiful feather figure in black walnut arises where a large branch merges with the main trunk. The two leaves are book-matched.

Figure 2-1. Many woods, such as these book-matched leaves of curly walnut, show light-colored sapwood alongside more deeply colored heartwood.

How wood grows

Wood grows by cell division: Cells divide outward to thicken and strengthen the tree’s branches and trunk, and new branch and twig cells also grow upward to allow the tree to compete for sunlight. The growing cells accept and transport moisture and nutrients, much like a sponge absorbs water. As new cells are added, the older cells die and strengthen. The outermost layer of cells just under the bark, where the actual cell division or growth occurs, is referred to as the cambium layer.

Figure 2-2. The way wood is sawn or sliced from the log determines the basic structure of its visible wood figure.

The dark-colored wood near the center of the trunk that ultimately supports the tree is known as the heartwood. Heartwood is most often used for woodworking. Sapwood, the layers of cells toward the outside of the trunk, transports sap, a mixture of moisture and nutrients, throughout the tree. Sapwood is often softer and lighter in color than heartwood, and is frequently discarded; however, particularly when matching veneers, the contrast in color between the heartwood and the sapwood can create a beautiful pattern to be used as a design element (Figure 2-1).

Wood cells are long, thin, and usually vertical. Individual cells cannot be seen by the naked eye, but long thin groups of cells known as fibers can be seen in most woods. The trunk grows outward during cell division, adding a new layer of wood each year. During the spring, a tree will grow relatively quickly, creating a layer of softer, lighter-colored wood. Then, in the summer and fall, growth slows, creating a denser, darker layer. The difference between the areas is seen as rings in the cross section of a tree (Figure 2-2), and cause what we see as the grain pattern in sawn boards. Different ways of sawing logs produce different grain patterns, as discussed on pages 20-21. Knowing how the cutting method affects grain pattern gives the craftsman a good idea of what to expect visually, a tremendous help in ordering and specifying wood and veneer.

Wood cells continue to absorb and give off moisture long after the tree has been sawn into boards or sliced into veneers. Summer’s high humidity causes the cells to swell, while low humidity and indoor heating during winter cause the cells to shrink. This expansion and contraction occurs across the width and thickness of the cells or grain but rarely along the length, and movement is much greater across the rings than in between them. Wood finishes can slow, but not stop, this seasonal movement of wood. Using quartersawn lumber (see here), however, can greatly reduce wood movement.

Wood figure and wood movement

Figure refers to the visual patterns that appear on the surface of the wood (Figure 2-3). The patterns occur for a variety of reasons, including the wood fibers themselves, genetic mutation, disease, stress, or chance. Unusual figure sometimes appears when, for example, a crotch or feather pattern develops where two branches come together. Burls (Figure 2-4), cancerlike growths often caused by a wound or insect infestation, sometimes develop near the roots or on the trunk of a tree. When cut open, burls often have a complicated grain pattern that travels in all directions. Other processes, including genetic mutation, cause curl, swirl, blister, quilting, mottling, and bird’s-eye patterns (Figure 2-5 through 2-10), but do not appear in all species of wood. Still another type of figure occurs when a tree has grown on a hillside or has partially toppled but continues to grow, creating compression of the grain on the underside of the trunk, and stretching of the grain on the upper side (Figure 2-11).

Figure 2-3. Waterfall figure ripples across a sample of bubinga, a tropical hardwood from Africa. The unfinished sample is flat; the three-dimensional effect is due to light refraction.

Figure 2-4. Burl veneer shows the irregular edge of its growth. The white lines indicate where it will be cut for figure matching.

Figure 2-5. Fiddleback figure in makoré, a rare hardwood, resembles curl or fiddleback in American maple, though it is more richly colored. The book-matched samples here also show the reversal in light refraction from one side of the veneer leaf to the other.

Figure 2-6. In quilted mouabi, the reflective whorls arise from the wood grain curving in and out of the surface. The two leaves here are book-matched.

Veneer TERMS

Clip, clipped. The process of straightening the long edges of veneer leaves is called clipping.

Flitch cut. Flitch cutting is slicing the veneer from a log along its length or from a slab (like peeling a carrot).

Flitch. A stack of veneer sheets sliced from the log and kept in sequential order, so the grain and figure match from one leaf to the next, is called a flitch.

Leaf, leaves. Sheets of veneer are also called leaves.

Rotary cut. Using a sharp knife to peel the veneer from a round log, similar to paper towels unrolling, is rotary cutting. The process is used mostly to manufacture plywood from crosswise layers of veneers and is used to cover large plywood and MDF panels with decorative veneers.

Wood grain, grain pattern. Long fibers that make up wood are the wood grain. Grain runs in the direction of the tree trunk, but it can also run toward a cut surface, “with the grain,” or away from it, “against the grain.” Grain is a factor in how wood appears.

Wood figure, figure pattern. The wood figure is the appearance of wood influenced by knots, straightness of the tree trunk, color changes between heartwood and sapwood, stains caused by minerals and chemicals in the wood, and marks made by weather, insects, or other trauma throughout the tree’s life.

Figure 2-7. This African satinwood veneer shimmers due to the refractive properties of the wood grain.

Figure 2-8. Curly, or fiddleback, maple veneer will show as lighter and darker bands when finished.

Figure 2-9. Pomele sapele shows many small blisters or bird’s eyes in its figure. This sample is flat—the three-dimensional effect is entirely due to light refraction.

Figure 2-10. Quilted figure is also common in sapele and bigleaf maple.

Highly figured woods are rare and valuable. In addition, particularly with the burls and such unusual figure as curl, bird’s eyes, and quilting, the grain often has grown in many directions at the same time. The drying process and later seasonal expansion and contraction may cause the cut wood to split apart if not handled properly. One way to prevent splitting is to initially slice or saw these woods into thin veneers because veneers are inherently more stable than thicker solid wood.

Many design and construction situations do not allow for any wood movement. Methods to compensate for movement in solid wood construction are limited. Quarter-sawing lumber is one such method. Quartersawn wood moves less in width and more in thickness, but because the boards are relatively thin compared to their width, wood movement is less of a problem. Another solution to wood movement involves frame-and-panel construction. In this method, a panel is placed in a groove within a frame and allowed to float without being glued in place. Floating allows the panel to expand and contract across its width without affecting the overall dimensions of the frame. Veneer offers another approach to dealing with wood movement that allows for much more design flexibility. When thin veneers are securely glued to a stable surface (called a substrate), any movement across the grain is nearly eliminated. (For a complete discussion of substrates, please see Chapter 4).

Figure 2-11. The leaning trunk of this black cherry tree shows compression rippling, which will appear as curl in the wood cut from it.

How veneers are cut

Because veneers are such an efficient use of a limited material, the best logs usually are separated and sent to the veneer mill. There, they are stripped of bark and milled to the size and shape that best utilizes the particular characteristics of each log. The way of cutting the veneer from a log will yield different grain patterns and types of figure. The resulting grain or figure pattern for each type of cut also will vary according to the wood species. The basic methods for cutting veneer from a log are illustrated in the sidebar on pages 20 and 21. All methods use a large knife to slice the veneer from the unseasoned log.

Rotary Cutting

Rotary cutting involves placing the log between two centers, then rotating it against the knife. As the knife moves in at a set distance and pressure, the veneer peels off, much like paper unrolling. The grain pattern usually is quite uniform but cannot be book-matched. Rotary-cut veneer is used for the face of construction-grade plywood as well as the core material of some plywood. Rotary cut veneer covers large areas quickly, without the need for seams, and is good for lower-cost surfaces that need a uniform appearance, such as doors, wall paneling, and plywood. Because there are few seams to telegraph through the paint, it also works well for surfaces that are to be painted. Bird’s-eye maple is one of the few types of premium veneer cut this way. Rotary cutting maximizes the number and consistency of bird’s eyes in each sheet.

Flitch Cutting

When sheets of veneer are sliced off the log (Figure 2-12) and kept together in sequential order, the resulting stack is known as a flitch (Figure 2-13). Veneer cut in this manner is referred to as flitch-cut veneer. Changing the orientation of the knife to the annual rings within the log creates a variety of grains and figures, which vary from species to species. Knowledge of wood characteristics is needed to best utilize each log. Veneer Slicing and Figure on pages 20-21 shows examples of common types of flitch cuts, and the resultant grain patterns and figures. To order veneer, the exact way the veneer is cut from the log is less important than knowing the types of grain and figure patterns available. Knowing the appearance of pattern and figure can create design possibilities and inspire new designs.

Figure in Veneer Species

Photos of veneers in my own inventory show examples of the color and figure available. Many of the species are not available as solid wood, and some, such as the pre-1992 vintage rosewood, are extremely rare. (Rosewood is protected; it is illegal to possess rosewood cut more recently than 1992). The samples have not been sanded or finished—what you see is the raw veneer. The examples are a fraction of the myriad of species and cuts available.

After proper orientation of the log and knife are established, the log is cut to shape and conditioned by being boiled or steamed in large vats of water or chemicals. The conditioning softens the wood fibers, allowing them to be sliced cleanly without tearing, ripping, or splitting. An additional run of the log through the metal detector helps operators find and remove nails or other items that might damage the valuable, vulnerable knife edge. Veneers cut with a nicked knife exhibit either a raised mark or a trough running diagonally across each sheet (Figure 2-14). Veneers cut with a dull knife will have grain torn out on every other sheet. Both defects can add a lot of sanding time, particularly with harder woods, and should be avoided.

Figure 2-12. A veneer-slicing machine moves the log against a heavy knife, which slices the veneer leaves. (Photo courtesy Erath Veneer Corporation.)

Figure 2-13. Flitch-cut veneers are carefully stacked in sequential order as they come off the slicing machine.

Clipping

Sheets of veneer are clipped, or cut straight along both long edges, to create sheets or leaves of uniform size with straight, uniform edges. Clipping usually removes the sapwood from each sheet.

Some wood species, and many burls, are available not clipped and have a rough or natural edge. With burls, which usually are odd-shaped before they are cut, the lack of clipping greatly reduces waste. Also, rough-edged veneers are good for capitalizing on the contrast between the sapwood and heartwood of a particular species because the sapwood has not been trimmed (Figure 2-15).

After clipping, veneer sheets are run though a dryer for specific times and temperatures, depending on thickness and species of wood. The sheets are then restacked in the order in which they came off the log and kept in a humidity-controlled environment until being shipped or used. Veneer sheets that require paper backing receive it at this point in the production process. Veneer without any factory backing or adhesive is known as “raw” veneer.

Buying veneers

After cutting and processing, the veneer is sent to a distributor. Large distributors cater mainly to large customers, providing rotary-cut sheets of veneer to plywood manufacturers for use as face veneer or paper-backed sheets of uniform, not unusual, quality to furniture and cabinet factories. Distributors are able to provide full flitches, which can number in the thousands of square feet. The rotary-cut sheets and paper-backed veneers are by no means bad. Large manufacturers of furniture, cabinets, and wall paneling want to be able to sell a consistent product nearly identical to the pieces they advertise, so color and figure uniformity is required. That requirement usually eliminates unusual grain patterns and figures from the veneered plywood and paper-backed veneer markets.

Medium and small distributors cater to smaller manufacturers and workshops looking for limited quantity, high-quality flitch-cut raw veneers. Most can provide anything from one sheet to an entire flitch (Figure 2-16), and there are hundreds of species available. Distributors and dealers can be found on the Internet. Most of these companies post photos of the veneer from the actual flitch you will be buying. In addition, there is an increasing number of businesses that sell veneer in joined, matched, and backed sheets, made of more unusual types of wood and grain patterns, for the high-end furniture and construction markets. Many of the distributors also sell tape, glue, and other veneering supplies.

Most distributors will send a small free sample upon request. Many sell sample packs containing 4" by 6" samples of twenty or thirty diverse woods, which are great to have around the shop for inspiration. I make sample boards of the most popular species by gluing a small piece of veneer to a thin substrate and then sanding and finishing it. Displaying the samples allows me to show clients what the finished product might look like. I also keep a fair amount of veneer inventory in my shop, so when I bid on a job I can make a sample board from the flitch of veneer I plan to use. I cut the sample in half, send the client one half, put their name on the back of the other half, and keep it, eliminating confusion later.

Flitch-cut, un-backed raw veneer is most often sold in lengths of 8' to 12' and known as full-length veneer, unless specified otherwise. Veneer also can be ordered in shorter lengths, which are referred to as shorts. Ordering veneer in an even number of sheets produces most matching patterns. Also, including an extra 15 to 20 percent more than you think you’ll need is beneficial because ordering additional veneer a few weeks, or even a few days, later will probably mean the flitch originally ordered from is gone or the grain pattern has changed, and the veneer will not match.

Figure 2-14. A nick in the slicing knife will leave a raised track across the face of the veneer.

Figure 2-15. These leaves of cocobolo have not been clipped—they retain the sapwood and the spreading shape of the tree trunk.

Figure 2-16. A flitch of fiddleback makoré shows a very similar pattern from one leaf to the next.

Veneer Slicing and Figure

The way the veneer mill slices the log affects the appearance of the veneer. The effect can be controlled by the orientation of the knife and log during the cutting process. There are two broad categories of veneer slicing: rotary and flat.

Rotary slicing

The log is placed between two centers and rotated while a wide, heavy knife is pressed into it, creating a long roll of veneer—much like paper unrolling. The figure repeats at intervals corresponding to the log’s circumference. Rotary cutting can be centered, off-centered, or split.

Rotary Slicing

Plywood is produced by rotary slicing. The process yields a continuous sheet of veneer with a consistent wavy grain pattern that generally repeats along the length. This method is very efficient and yields large sheets of veneer with a consistent grain pattern, but it does not necessarily create interesting figure and character.

Half Round Slicing

In this method of slicing, the veneer closely follows the annual rings in the log. The result is wide, closely matched sheets with a wavy grain pattern. This veneer is good for covering large areas with a plain figure. This slice will also produce the most eyes in bird’s-eye maple.

Rift Slicing

This method can produce a linear grain pattern that closely resembles a common rift-sawn board. In some species rift slicing will emphasize the figure pattern known as mottling.

Flat Slicing

In flat slicing, the log is held stationary with respect to the knife, which advances into the log by the thickness of each successive leaf. Most veneer slicing machines have a stationary knife. A heavy apparatus grips the log, moving it up and down against the cutting edge. Flat-sliced veneers can be crown cut, quarter sliced, or quartered and then flat sliced.

Plain Slicing (Flat Slicing)

Plain slicing is the most common method for producing flitch-cut veneers. It produces exactly matched consecutive sheets of veneer with a grain pattern resembling a flat-sawn board. The pattern will change slightly as the knife moves deeper into the log. If the edges are not clipped, some sheets will have uneven edges or will contain sapwood, which can be used to create interesting contrasts in color.

Quarter Slicing

Quarter-slicing will produce exactly matched quarter-sawn sheets with a strong linear pattern. It can also emphasize mottled figure in some woods. The quartered logs also can be rotated 90° to slice the veneer starting from the outside of the trunk, tangential to the curve of the annual rings. This will maximize the yield of quilted figure, which usually appears only near the surface of the log.

Lengthwise Slicing