Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

What really makes the royal family tick? It's a question that royal watchers have pondered for as long as the monarchy has existed. And who better to ask than the army of servants and staff past and present who feed and clothe the royals, organise their days, polish their shoes, carry the deer and pheasants they shoot and even put the toothpaste on their toothbrushes? From medieval times, when the Groom of the Stool oversaw the monarch's lavatorial exploits, and courtiers accompanied the king and queen to bed on their wedding night and made bawdy remarks until ushered out of the room, below-stairs staff have had a unique insight into the lives of their royal masters. In this lively and colourful history, royal expert Tom Quinn goes behind palace doors to give a compelling glimpse of Britain's royals, ancient and modern. Here you will find the tales of the equerry who threatened to throw Queen Victoria out of her own stables, the junior footman who had to change his name on the orders of the queen, and the lady in waiting who, with Prince Philip's mother Princess Alice, regularly set fire to her rooms at Buckingham Palace. Perhaps most intriguing of all, we see, through the eyes of serving and recently retired staff, how today's royals live – including how the relationship between Meghan and Harry and William and Kate started with high hopes and descended into bitterness and anger.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 364

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

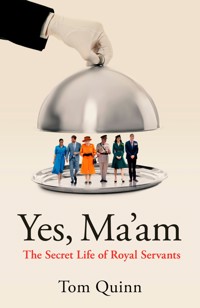

Yes, Ma’am

The Secret Life of Royal Servants

Tom Quinn

Contents

vii

‘One doesn’t think much about one’s ancestors… They might be a rather bad influence.’

– Queen Elizabeth II, to the author

‘There is, at all Courts, a chain, which connects the Prince, or the Minister, with the Page of the Back-stairs, or the Chambermaid. The King’s Wife, or Mistress, has an influence over him; a Lover has an influence over her; the Chambermaid, or the Valet de Chambre, has an influence over both; and so ad infinitum.’

– Lord Chesterfield, Let ters on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman, 1774

viii

Introduction

‘Children? Yes, I suppose some people see them as a sort of punishment…’

– Prince Philip, to the author

We are all intrigued by our own family histories and when we begin to delve into the past, most of us discover that long ago – and sometimes not so long ago – a family member worked as a servant. This is hardly surprising given that in 1900 there were an astonishing one and a half million people in the United Kingdom working as domestic servants.

Most were women from poorer backgrounds who were expected to work twelve-hour days six or six and a half days a week from the age of twelve or fourteen.

My own interest in the lives of domestic servants – including royal servants – began with my mother’s stories of working as a fifteen-year-old kitchen maid in a big house in Ireland in the 1940s. Much of the work was back-breaking and tedious, but the saving grace was, as my mother put it, ‘those marvellous girls I xworked with; the great gossip we had and the fun’. The fun included swimming in a lake on the estate, sleeping on the roof on hot nights in summer, shinning up a tree to escape the attentions of a ‘frisky gardener’ and gossiping about the family. For servants of the British royal family, the work might be just as exhausting, but there could be even more fun – who, after all, could resist life in a great palace, where so often even a humble kitchen maid became privy to the secrets of one of the most famous families in the world?

For centuries, servants were cheap and so the houses of the rich expanded, as it were, to accommodate them. Indeed, by the end of the nineteenth century, country houses were being built on such a scale that the servants often had to run from the kitchen to the dining room if the food was to be served warm.

After the introduction of inheritance tax and the changes wrought by two world wars, the vast houses and their rolling parkland found themselves deserted by servants, who preferred factory work. The mansions became unmanageable or were simply abandoned, and they began to be demolished: more than 1,000 big country houses were torn down in the century after 1875, according to the curators of a famous 1974 exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum.

But while all this was going on, one family at least was able to keep its mansions and palaces going, continuing to employ vast numbers of servants, as it still does today: the royal family.

For this glimpse into the hidden world of the royal servant I have themed each chapter to see how, for example, the kitchen staff or the ladies in waiting have changed over the centuries. To xithis I have added stories told to me by royal staff on the strict understanding that informants’ identities were protected. Some royal staff jobs have now vanished, but even when those jobs were filled there was something mysterious and highly secretive about them – what exactly did royal jesters and fools do, for example, and why were they employed for so long? There are also chapters on the outdoor staff – the gillies and gamekeepers – as well as chapters on what goes on in royal bedrooms and in the kitchens.

In this book I’ve tried to avoid over-emphasising the dull routine of a royal servant’s life; there is little need for a blow-by-blow account of the servant’s day, nor for a precise account of who reported to whom and exactly what each was paid. Instead, I have tried to provide a more impressionistic account of the world of royal service, an account that focuses more on the telling anecdote than on the exact tally of buckets of coal carried upstairs at Buckingham Palace or Balmoral. I’ve included servant tales that bring to life the ups and downs, the eccentricities and intimacies of such close proximity to the only family in Britain that still lives, in the domestic sphere at least, as it did in the eighteenth century.

The idea is to get behind the surface view of royal service, a view with which we are already familiar and which can be read about in countless books. In order to find out what really goes on below stairs – and indeed on the backstairs – we need to go through the green baize door to the hidden world that supports a small number of glittering stars – the kings and queens, princes and princesses we know almost too well.

Here you will find the stories of the equerry who threatened xiito throw Queen Victoria out of her own stables, the king who preferred his parrot to his children, the courtiers who couldn’t understand a word their new king said.

Other stories include the tale of the junior footman who had to change his name because Queen Victoria was horrified to learn he was called Albert (how dare a servant have the same name as her beloved husband!); how the late Queen Mother fell into the arms of one of her gillies while fishing and would regularly shout at the salmon in the river Dee at Balmoral; and how Prince Edward once told his driver to stop looking in his rear-view mirror.

Moving closer to the present, we find Queen Elizabeth II trying to fix a picnic table and insisting that using a screwdriver is far more difficult than being queen; Prince Philip worrying that if his son Charles read too much poetry, it might make him gay; and Prince Philip’s mother regularly setting fire to her rooms at Buckingham Palace.

The final part of the book looks at the huge complexities of living with royal staff in the modern world; seeing life through the eyes of staff at Kensington Palace, for example, we glimpse Meghan Markle dancing with Prince William and terrifying an Old Etonian equerry by trying to hug him!

Perhaps most intriguing of all, we see, through the shrewd commentary of serving and retired staff, how the relationship between Meghan and Harry and William and Kate started with high hopes, fun and happiness and slowly descended into bitterness and anger.

As this book tries to show, the lives of royal servants, from xiiibelow-stairs staff to senior advisers, give us a unique and uniquely intriguing glimpse into the royal family, ancient and modern. Here you can see them – everyone from the grandest courtier to the humblest kitchen maid – as they have never been seen before.xiv

Chapter One

Why everyone wants a servant

‘Ineverlikedanimalsquiteasmuchasmywifeorchildren –excepteatingthemofcourse.’

– Prince Philip

To understand the secret lives of royal servants, it is essential to understand the history of monarchy and the social hierarchies that underpin it, because those hierarchies have survived remarkably unchanged from medieval times right up to the present.

In the Middle Ages, everyone, from earl to kitchen maid, was effectively the servant of the monarch. Kings controlled the lives and fortunes of the landed aristocracy; the aristocracy controlled everyone else. The vast bulk of the population could be described as landless, illiterate serfs. They had no rights and no property; their daughters and wives and they themselves were entirely at the disposal of the local landed aristocrat. That aristocrat in turn held his land entirely at the whim of the monarch. All the most senior aristocrats in the land – the barons, earls, lords, knights 2and baronets – worked with and for the monarch because to do otherwise was to arouse suspicion. A great lord who did not attend court would quickly fall under suspicion: he must be plotting rebellion. Why else would he not attend his king, his lord?

So, in a sense, in this early period everyone was a servant and every class, except the very lowest, in turn had their own servants. Servants, as serfs or villeins, were effectively property in the Middle Ages and then slowly over the centuries they became paid servants and then, as they are known today, staff. To own villeins, to have servants and to pay domestic staff was and remains a key part of what makes the aristocracy and the royal family different from the rest of us.

The highest ambition of the aristocracy and the royal family traditionally is to show that they do nothing menial for themselves. When the rising middle classes grew wealthier in England in the eighteenth century, they wanted above all else to ape royalty and the aristocracy by also paying others to do their dirty work. To be part of the leisured classes was to have arrived. And this aspiration lasted well into the twentieth century and to some extent continues into the twenty-first.

I can remember my own mother-in-law’s proudest boast was that she had never had to work; she had employed a full-time nurse for her children as well as a nanny, a cleaner, a gardener and a housekeeper. She always looked astonished when I asked what she did while the nurses and nannies were looking after the children. ‘Why, nothing I suppose, but I had a busy social life having tea with friends and shopping.’

This desire of the middle classes – even the lower-middle 3classes – to have at least one servant – a maid of all work, as she was known in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – was linked to the desire to move up the social scale. Only the very poorest could not afford at least one skivvy. Aristocrats might have hundreds of servants. The monarch might have as many as a thousand.

Servants conferred status; the British obsession with class held and still holds that the highest social classes are most esteemed because they can afford to pay other people to do everything for them.

This book is about royal servants and their relationships with each other and with those who employed them, but it is also about how royal servants themselves sought status by having servants of their own; the world below stairs was just as socially stratified as the upstairs world of kings and queens. Well into the twentieth century, senior servants treated lowlier servants with the same kind of disdain and haughtiness with which they themselves were treated by those who employed them and by those who were even farther up the servant hierarchy.

Of course, the higher up the social scale one happened to be, the greater the range of servants, until at the very top we find the royal family keeping people to work for them but also, in earlier times, to amuse them; at its worst, the royal family even kept people as little more than pets. These, if you like, are the secret servants of the royal family whose lives we will try to explore in this book.

Then there are the vast numbers of servants who were employed rather than simply kept – though, as we will see, the line 4between being kept as a companion and employed as a member of staff was often blurred. Henry VIII kept a fool, a jester, who was fed and clothed but never paid. Elizabeth II paid her senior staff, her courtiers, but many of them felt – as they would have felt with no other employer – that they simply could not leave and seek employment elsewhere and were lucky to be offered the chance to be royal companions, paid or unpaid. As they had numerous servants themselves, being a royal companion gave them something to do that was not tainted by the idea it might involve any work.

Queen Victoria’s ladies in waiting were paid handsomely, but they would have been horrified at the suggestion that they were really just foot soldiers in that army of people paid to be at the beck and call of the monarch. It was only snobbery and an obsession with status that refused to accept that a paid companion wasn’t that different from a paid nanny or footman or gardener.

* * *

The secret lives of all royal servants, whether companions or below-stairs staff, are fascinating, and though we can only piece together their lives in earlier ages through historical records, many of which have only become available more recently, the situation is easier as we move into the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Many of the dozens of royal staff I have spoken to over the past four decades can recall life as a servant in the royal palaces 5going back to the 1890s because their parents and sometimes grandparents were also employed by the royal family.

One of the interesting changes this book also examines is how ‘servant’ became a dirty word; all royal servants are now known as royal staff. The change is a recognition that historically there was always something slightly demeaning about being a servant – what Victorian domestic servants called the ‘shame of cap and apron’.

What made being a servant demeaning was not the work itself but the acknowledgement by society itself that servants were a lower sort; they were inherently inferior to their masters, whether royal or otherwise.

And it is certainly true that we have moved from employers, including royal employers, deliberately emphasising their superiority to a situation where, quite rightly, royal employers are permanently terrified they will be accused of treating their servants as inferiors.

But what was formerly explicit is now implicit. The royal family now treat their staff with consideration and at least superficially as equals, but the old social barriers are still there and just as difficult to cross as ever they were.

Where medieval servants often slept on the floor, a member of the royal staff today may have his or her own flat at Buckingham Palace or a cottage in the grounds of Windsor Castle. But he or she will not be invited to tea.

There has been a vast change in attitudes, but deference, however uneasily maintained, is always there. Even today we suffer 6from a lingering sense of awe at the idea of the landowning aristocracy, which is to a large extent what royalty is; we think of them as somehow special. To work for them in any capacity is, for some, to be especially privileged; to work for the royal family, the ultimate aristocratic family, even more so.

Royal staff frequently stay in post for life and they are fiercely protective of their royal employers’ secrets. It is almost as if some version of the famous Stockholm syndrome is at work: we may recall that kidnap victims often grow to sympathise with, even, support their captors. Something similar happens with royal staff and it is a phenomenon as old and as inexplicable as the royal family itself.

* * *

There has always been something secretive about life in royal service – the royal family don’t really want people to know exactly what the royal gamekeepers do to ensure there are enough pheasants for a shooting day, for example. They don’t, as Princess Margaret famously said, want to tell people what they had for breakfast or what sort of loo paper they use. They don’t want the private thoughts of below-stairs staff to be more widely known, but the royal family – or The Firm as the late Diana Spencer called it, using a phrase coined by her father-in-law, Prince Philip – employs a wide range of people from an extraordinary range of backgrounds and as with any group of disparate people who work together there are disagreements, petty jealousies and examples of outrageous and eccentric behaviour. Life as a servant 7in the royal family is by turns bizarre, entertaining, mundane, intriguing and rich in gossip and backbiting.

Perhaps most interesting of all are the stories the servants have to tell about their day-to-day experiences living with and attending to members of the royal family. Some of these stories reflect badly on individual royals, but others show the kindness and deep affinity royal family members occasionally have with their staff – and, as we will see, both aspects of servant life in the royal family have been true for as long as we have had a royal family.

The curious nature of royal service – that staff often feel uniquely privileged, just as their ancestor servants must have felt – has two important effects: first it tends to engender loyalty, especially if the staff are aristocratic companions (courtiers and ladies in waiting), and it occasionally creates uniquely close bonds even between relatively lowly staff and their masters. It is this close bond, an intimacy that does not always happen in other areas of employment, that has produced many of the stories recounted here. They are stories that reveal the strange, amusing, often bizarre, but until now largely concealed side of a unique family and a unique way of life.

Many biographers and historians today adopt a chiding tone – we writers are constantly on the lookout for ways in which the past fails to live up to our standards. It is as if we cannot believe that our own mores will, in turn, come to seem foolish, archaic, perhaps callous, a century or more from now; I have kept that very much in mind while writing this book.

Much of Yes,Ma’amconcerns how history, and especially the history of the royal family, is about making friends and 8influencing people. We like to think that nepotism, jobs for the boys – whatever we like to call it – is largely a thing of the past or a thing that afflicts dictatorships elsewhere in the world but not us. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth.

Britain never scores particularly well on the Transparency International corruption perceptions index because corruption is embedded in today’s society much as it was in the past. Let’s take a few examples: a large payment to a political party will often guarantee a peerage; ministers and MPs regularly leave political life and move into extremely lucrative jobs with private companies who are employing them solely in the hope that they will be able to influence former colleagues in Parliament; some ministers leave politics and within months have secured a dozen or more lucrative jobs for which they have few qualifications other than their previous influential positions. One former Cabinet minister left politics to become the editor of a national newspaper while having little experience as a journalist.

So, when we look at the past, at the royal court in Tudor, Elizabethan or Victorian times, we should resist the temptation to condemn. As power shifted from the royal family to Parliament, corruption moved with it, but the royal family’s social status remained and for those who love status, the appeal of working as a servant for the royal family remains as strong as ever.

* * *

In the next chapter, I look back at the history and context of power that has produced the modern royal servant. That he or 9she feels different from other servants, and indeed from people doing other paid jobs, is entirely the product of more than a thousand years of royal and aristocratic history.10

Chapter Two

Everyone is owned by the king

‘We have school fees and staff to pay,houses to keep up –that’swhywegetpaidratheralot.’

– Former courtier, author interview

‘IhopeI’mnotatouristattraction.’

– William, Prince of Wales

After William the Conqueror’s victory at Hastings in 1066, everything in England became – overnight, as it were – the new king’s property. And by everything we really do mean everything – land, houses, animals and people, with the possible exception of the many religious houses, monasteries and abbeys. These last were nominally the new king’s property, but no English king at this time would have interfered with a realm under the jurisdiction of the Pope.

Land owned by William by right of conquest is still owned by the crown. Even today, the presumption is that if land can’t be proved to belong to someone else, it is the crown’s. And what 12does the crown own? Well, it owns 286,000 acres of agricultural land in the UK; it owns all of London’s Regent Street and half of St James’s; it owns more than half the UK’s foreshore (coastal land under water at high tide) and it owns all the gas, oil and coal under the seabed out to twelve miles from the coast.

Crown Estate profits in 2023/24 reached £1.04 billion. Now, only a portion of this goes to the royal family, but the amount is decided not by Parliament but privately by the Prime Minister in private consultation with the royal household. The monarchy gets 12 per cent of Crown Estate profits each year (known as the sovereign grant) and the sum is predicted to be £124.8 million in 2025.

But on top of this and entirely originating, like the Crown Estate, from William’s victory at Hastings is the income King Charles receives from the Duchy of Lancaster, a huge estate of land and other property that produced £27 million income for the king in 2023/24. The Duchy of Cornwall produced similar profits for William, Prince of Wales.

Apart from these monies – from estates that cannot be sold – King Charles’s private wealth is estimated at somewhere between £600 million (according to the most recent SundayTimesRich List) and £1.8 billion (according to TheGuardiannewspaper). His private investment portfolio even includes rental property in Transylvania.

Given this extraordinary medieval level of wealth, is it any wonder Charles and other members of the royal family employ hundreds of gillies, gardeners, footmen, press officials, bag 13carriers, butlers, maids, stable hands, grooms, nannies, equerries, private assistants, secretaries and chauffeurs?

Land was always the key to power and prestige, and land was William I’s to give or withhold. With the land ownership came peasant ownership: all the villeins who lived on the newly conquered land provided the lower servants for the new lords in their soon-to-be-built castles. Britain’s richest landowner, the 7th Duke of Westminster, would not be Britain’s richest landowner today if his ancestor who fought alongside William at Hastings had not been gifted a huge chunk of the newly conquered country by his friend the king. Westminster’s wealth, like that of the monarchy, is effectively the spoils of war writ large.

The pattern of land ownership we see in Britain today still echoes the gifts of land given to his favourites by William I, but until relatively recently the land held by the nobility could be and occasionally was confiscated from even the greatest nobles.

Aristocrats stayed close to the monarch, advising and entertaining him, mostly to ensure he (or she) remained convinced of their loyalty. The monarch controlled, effectively owned, his nobles; the nobles in turn controlled, indeed owned, those who lived on the lands they were given by the king. The nobles were kept in check by the threat of violence and the ordinary people were kept in check by the same means.

No one should think for a minute that the knowledge that the royal family’s wealth has come to them simply through an ancient act of war lessens the ruthlessness with which the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall are now managed. Royal wealth 14gained and held by the threat of violence in medieval times is now held and managed using the law and the threat of legal action. When, for example, Bristol City Council wanted to build a footbridge over the river Avon for the use of local citizens, the Crown Estate demanded more than £117,000 as its fee for what was described as an ‘air-space levy’. The original fee demanded was £300,000, but after years of legal argument it was reduced. The fee was charged because since the conquest the monarch has owned the riverbed!

The execution of Charles I established that the monarch did not have absolute rights and absolute power; that land and property could no longer be appropriated at the whim of the monarch. As time passed, we came to believe that the great traditional landowners – the Dukes of Bedford, Westminster, Atholl and Beaufort, among many others – had somehow earned their wealth and land. In fact, they had simply hung on to what had been given them by one violent king or another; they had hung on into an age when there was no danger they might lose their land by the very means with which they took possession of it in the first place – currying favour.

I mention all this simply to drive home the point that for centuries everyone was a servant because everyone feared their livelihoods and status – and land – might vanish in an instant if they displeased the monarch. Monarchs were happy to be loved – both by their aristocratic servants and by those lower down the social scale – but they preferred to be feared. And as the nobility feared the violence of their master the king, so too did the peasantry fear their overlords. Only the small merchant class 15in medieval England seem to have escaped some aspects of the crushing power of the violence of hierarchy; certainly, they were subject to the crown, but they were not owned in the way the villeins were owned, nor were they subject to the whims of the monarch in the same way as the aristocrats. Their wealth came from trade, not land, and monarchs have always been careful not to interfere with trade since the wealth of a nation depends on it. When William the Conqueror defeated Harold and took control and ownership of England, he gave his followers land, but he didn’t hand the City of London over in a similar way; instead, he sold it back to the merchants who had created and maintained its wealth. It was an acknowledgement that, small in number though they might be, the London merchants were somehow different.

* * *

Geneticists tell us that human faces, like all ape faces, have evolved to be flat, relative to most other mammals, because apes are violent, quarrelsome creatures that fight continually. If you have a flat face and you fight not by biting but by punching, you are less likely to suffer a serious facial injury in a fight compared to a mammal with a snout. As human societies evolved, fighting became ritualised and organised but no less frequent. According to Chris Hedges, writing in the NewYorkTimesin 2003, the best guess is that ‘of the past 3,400 years, humans have been entirely at peace for 268 of them, or just 8 percent of recorded history’.

Through war and conquest, both external and internal, all 16human societies have worked out some sort of hierarchy and just as ape societies establish hierarchies through violence, so too human hierarchies are or were originally established on the basis that might is effectively always right; the biggest, toughest ape is always at the top. Even today when there is a coup in a particular country it is often the head of the military – the biggest ape – who takes over.

I make this point at some length because traditional monarchies are rather similar, with the most powerful individual at the top by right of birth and everyone below that individual subservient to him or her. Before modern democracy in England, might always made right, which is why at Bosworth Field, in 1485, for example, Henry Tudor was able to kill Richard III and become top dog (or top ape) with absolute power over everyone from the greatest earl to the lowliest ploughman. No one has ever felt sorry for Richard, because he would have killed Henry just as readily as Henry killed him. In this case, as so often in battles between rivals for a throne, might made right and the winner took everything.

If we go back much further to discover the origins of monarchy (and the origins of royal servants), we can safely assume that violence lies close to its heart.

Archaeological evidence strongly suggests early farming communities in England and Europe made their own decisions about how to live in what were often remote, isolated areas. Squabbles and fights no doubt there were and the toughest and most persuasive no doubt usually got their way, but this was small-scale stuff.17

Then came bands of armed knights – in TheTimeTraveller’sGuidetoMedievalEngland, Ian Mortimer refers to them as ‘brigands’ – who laid claim to large tracts of land that included many small, formerly self-governing farming communities. The knights told the farmers that all the land they farmed and lived on was now owned by the knights and that they would kill anyone who disagreed. For a more recent example we need look only to Australia, where Captain Cook planted the British flag in 1770 and claimed the whole of the island continent for George III. Behind the claim was the knowledge that the indigenous people did not have anything like the might of the British crown to dispute the assertion. Australia today is run by the descendants of Europeans because those Europeans were better at killing the original inhabitants than the original inhabitants were at killing the Europeans.

Ancient isolated farming communities were subdued by force and the knights – the brigands, or criminals, if you like – made themselves overlords, a situation that in many ways continues to this day, especially if one believes the old dictum that property is nine-tenths of the law. When the brigands took control of the land, they took control of people on the land.

But the knights were in turn eventually controlled by a more powerful force as one among them became first among equals and then, to use a phrase made famous by George Orwell, some found themselves to be more equal than others and thus were kings gradually established as overlords of the overlords.

But what has all this to do with the lives of royal servants, you may ask? Well, in a sense all royal servants, from the lowliest 18kitchen maid to the most aristocratic courier, are descended from servants and aristocratic companions whose roles were fixed a thousand years ago. And though the threat of violence has largely vanished from these relationships, the social gulf between maids and monarchs, lords and earls remains.

By the later medieval period, almost everyone worked for the monarch or the nobility. The land the common people worked was owned by the local lord, who would take a percentage of their produce each year. They could never own their land, they had a duty to fight for their lord if he went to war and, as Ian Mortimer points out, their masters had control not just of the lives of the villeins but also of their bodies. If a villein’s daughter married a peasant owned by a neighbouring lord, the girl’s father had to pay his master not just for the loss of the daughter but also for the loss of the children that daughter would be assumed to produce. This may seem extraordinary today, but then universal human rights are both a social construct and a very recent phenomenon.

And if the landowner wanted to rape a female peasant, it was simply accepted that he had the right to do it. In a diluted form, this kind of power – the power of master over servant – survived as late as the early twentieth century. In her 2012 memoir TheMaid’s Tale, former maid Rose Plummer’s account of her days in service, she recalls how aristocratic employers saw the sexual harassment of female staff, some as young as twelve, as perfectly acceptable.

Aristocrats and the royal family have only very recently come to terms with the idea that their servants are entitled to their 19own lives. But even though formally no longer serfs and villeins, royal servants have been subjected to an informal yet powerful pressure emanating from the unthinking assumption that royal needs must come first.

When Marion Crawford told Queen Mary she wanted to leave to get married after twenty years of royal service, for example, Queen Mary was indignant. She told Crawford that it was quite impossible and asked how on earth Crawford expected the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret to manage on their own. Not one word about Crawford, her life, her desire to marry or her future husband. Lower down the social scale, the same assumptions persisted: in his semi-autobiographical novel Buddenbrooks, Thomas Mann explains how it was simply assumed in the family that Ide Jungmann, their servant, would work for the family, without marrying or having children, until she died.

Royalty and the aristocracy have always resisted reforms to the way they manage their estates and their servants – as late as 1909, the House of Lords, at that time overwhelmingly dominated by hereditary peers, rejected the idea that a small basic pension should be introduced by the government for the poor. Hereditary peers at the time insisted that theywould provide for their pensioned-off estate workers – but only if they chose to do so.

* * *

I argue in this book that royal servants are in many ways the direct descendants of the villeins, the slaves, who worked without pay and without rights for those medieval kings and their brigand 20aristocrats. Gradually, societal changes – most especially the execution of Charles I, which destroyed the idea that the monarch could do as he pleased – led to former serfs and slaves being paid and enjoying limited and then gradually evolving rights, but at least until the twentieth century most of those rights taken from the monarch were taken in order to protect the privileges not of the servant classes but of the nobility.

Royal servants have always been part of the endless battles for power. If you could kill a king, you could become one. But then you needed the safety of loyal retainers to ensure you kept what you had taken. After Henry VII killed Richard III at Bosworth, he knew his hold on the crown and his right to that crown were shaky. To protect his weak position, he made sure the servants with whom he surrounded himself were not drawn, as they traditionally would have been, from the upper echelons of the aristocracy. That was too dangerous, as the nobles might have done to him what he had done to Richard III. So, for Henry VII’s reign the gentry found themselves in elevated courtier positions previously held only by the aristocracy. Instead of being an earl or a lord, Henry’s Groom of the Stool, for example, was Hugh Denys, the son of a Gloucestershire farmer.

* * *

‘They also serve who only stand and wait’ – that famous phrase from John Milton fits nicely with the theme of this book, because according to many former and serving royals servants I’ve 21spoken to there is an awful lot of hanging around when you work for the royal family.

But while they are standing around, or fetching or carrying, advising or comforting their royal masters, royal servants (or staff as we must now call them) are more aware than anyone of what really goes in in the royal palaces: they see at first hand the squabbles and petty jealousies, the arguments and tantrums that inevitably take place in what is by any standards one of the strangest families in the world. And royal staff frequently have unique insights because they are descended, in some cases quite literally, from those early villeins and flattering nobles; that they are expected to have a higher level of devotion to their work and their masters than staff who work for other families is entirely a legacy of the old order examined in the previous chapter.

Royal staff may in some senses still be treated like serfs, but they are also acutely aware of the upside of working for the royals in the twenty-first century. The royal family is so nervous of criticism that staff are now treated very well – although salaries are still often poor – and modern royals at least attempt to put on a more human face. It is too easy to assume that the royals are invariably dull, serious, demanding and unkind both to each other and to the people who work for them. That is sometimes true but by no means always – as a member of the Kensington Palace staff explained to me:

They [the senior royals] can be really light-hearted and jokey with each other – the late Queen and Prince Philip were a hoot. 22Occasionally, I had to ask to be excused before breaking down in fits of giggles. I once forgot myself in front of them and almost dropped a valuable plate. I instinctively mumbled, ‘Oh shit.’ The Queen spluttered as she started to laugh and said, ‘Well, quite.’

The key point is that royal service is still somehow special; royal staff certainly don’t see themselves as serfs but they are expected to be highly discreet – highly secretive – and to see working for the royals as somehow a special privilege. In this sense, royal staff echo the ancient idea of serfdom in which service to a noble or a king is seen as its own reward.

Many royal staff endure long hours for little pay, sometimes for the whole of their working lives, simply because they are so dazzled by the idea that they are working for the royal family, even if they are only in the kitchen. And there is still an obsession with social hierarchy in royal service – an obsession that would not be unfamiliar to royal staff 600 years ago.

Senior staff, especially courtiers, are still mostly aristocrats or at least public school educated; in some cases, they are descended from families that have worked for the royal family for centuries – the Keppels, and the Dukes of Norfolk, for example. Courtiers do not see the kitchen staff as their equals – one courtier I spoke to about the vastly different salaries of aristocratic staff compared to domestic staff said, ‘You see, they simply don’t need a great deal of money – after all, they don’t need to pay school fees as we do.’

* * *

23It is difficult to imagine now, but servants have always been just as snobbish as their employers, perhaps even more so. Only the inexperienced or desperate would work in a small household with one or two servants; the aim was to work for the nobility at least, and that was often seen as a stepping stone to the ultimate in servant status – the royal family.

But if a servant couldn’t quite make the royal family, he would do almost anything to escape working in a middle-class household. A valet describing his life in ToilersinLondon, published in 1889, said, ‘It’s only the aristocracy who treat servants properly … The aristocracy know how to behave to a gentleman even if he happens to be a servant.’

It’s easy to think everything in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – perhaps the heyday of servant life – was serious and worthy, rather as we think of that world as monochrome simply because photographs and film from the time are black and white. There wascolour and there wasfun and surprisingly that was especially true in the royal family. The middle classes, always worried about their status, felt it was proper and more refined to be harsh with their staff; the royals, by contrast, often treated their servants extremely well. The late Queen Elizabeth II loved joking with her staff – standing next to one of her security team on one famous occasion outside the gates of Balmoral, she was asked by a passer-by (who clearly had no inkling who this tiny woman in a headscarf was) if she had met the Queen. Without a flicker, the Queen replied, ‘No, but he has.’ At which she pointed to her security detail.

Similar examples are legion and I have one from my own 24experience. I was allowed to be part of a small group surrounding Queen Elizabeth at a large country show; I’d been given special permission to join her entourage as she had heard I was there on behalf of one of her favourite magazines. Unfortunately, her security detail did not seem to be aware of my special permission and I suddenly found myself unceremoniously manhandled away from the Queen. The Queen stepped across to where I was being dragged away and said, ‘He really isn’t a rabbit to be picked up by the scruff of the neck, you know. I think you can safely put him down. He looks fairly harmless.’ And with that I was released with a grudging apology from a very fierce-looking but rather small (and absurdly well-spoken) security man. As we continued on our way, with the Queen herself a yard or two ahead, I asked my assailant if he had to carry interlopers off frequently. ‘Secrets of the trade,’ he replied. ‘Happens all the time. Most people who get too close are harmless, but you never know – it’s the little old ladies that worry me. I can boot you over a hedge, but I can’t do that to Mrs Warren aged eighty from Tunbridge Wells who might be angry with the Queen for some unknown eccentric reason and want to whack her with an umbrella. And I can tell you, I’ve had to deal with the umbrella brigade a few times.’

* * *

Most of the major changes that have transpired in the way royal servants are treated occurred during the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. Earlier generations had not felt the wind of egalitarianism blowing as Elizabeth did. Queen Mary, her grandmother, 25disliked ever seeing any of the lower servants bustling about her various palaces, and a strict regime ensured that cleaning and cooking went on well out of her sight, but then she had grown up in an age when lower servants were seen as a necessary evil.