Ypres Diary 1914-15 E-Book

9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

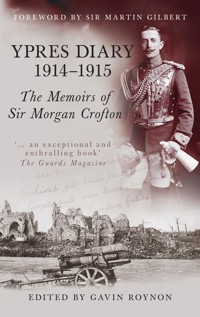

Sir Morgan Crofton fought in the Boer War and joined the 2nd Life Guards at 34 years old as a cavalry office. His diary charts his experiences on the front-line at Ypres from late October 1914 to the centenary of Waterloo in June 1915. Crofton describes a battlefield a world away from what he and any of his comrades had experienced before - one of staying still in trenches, being pounded by artillery and the terrifying new power of machine guns. He describes the bewildering pace of technological change as new weapons, such as gas and hand grenades entered the fray. His often acerbic commentary offers a fascinating glimpse into the mindset of the regular officer class and his outspoken scepticism informs our understanding of a lost generation of professional soldiers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

YPRES DIARY 1914–1915

YPRES DIARY 1914–1915

The Memoirs of Sir Morgan Crofton

EDITED BY GAVIN ROYNON

FOREWORD BY

SIR MARTIN GILBERT

To my son Nicholas who shares my love of history and accompanied me on my first visit to Ypres

First published 2004

This edition published 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© Gavin Roynon, 2004, 2010, 2011

The right of Gavin Roynon to be identified as the Editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 9780752469737MOBI ISBN 9780752469744

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Foreword by Sir Martin Gilbert

Acknowledgements

Maps of Western Front and Eastern Front

Ypres Then and Now – Editor’s Note

Biographical Note on Lieutenant Colonel Sir Morgan Crofton, Bt DSO by Edward Crofton

VOLUME I: OCTOBER 27 – DECEMBER 3, 1914

Sir Morgan Crofton leaves for the Front – arrival at Le Havre – continues via Rouen and Hazebrouck to Ypres – rejoins severely depleted 2nd Life Guards – put in command of Machine Gun Section – plight of horses – take-over from Somersets in the trenches – hauling out the corpses – death of Trooper Boyce – Dick Deadeye – wreckage of Zillebeke – new billet in Girls’ School at Eecke – ancient Cloth Hall at Ypres destroyed – three prisoners court-martialled – visit of HM The King and HRH The Prince of Wales.

VOLUME II: DECEMBER 4, 1914 – JANUARY 5, 1915

French 75mm field gun ‘the best in Europe’ – Archie Sinclair meets Churchill – battle-cruisers lost at Coronel – future of cavalry debated – organises new billets at Staple with the ‘Ancient Mariner’ – another girls’ school commandeered – ‘nothing succeeds like excess’ – visits Lt Col Trotter in hospital – officer casualties – news from the Eastern Front – three days’ leave – attends Hilaire Belloc lecture – his third Christmas on active service – receives presents from Princess Mary – aeroplane raid on Cuxhaven – New Year’s Eve ‘banquet’ – football against the Leicesters – Auld Lang Syne – bathing parade in the brewery – institution of the Military Cross – New Year greetings from Joffre.

VOLUME III: JANUARY 6 – FEBRUARY 18, 1915

Rides to Cassel, where Foch has his Headquarters – censors men’s letters – experiments by French artillery – effects of the blockade within Germany – à Court Repington’s article in The Times – Russian victory and huge Turkish losses at Sarakamish – resignation of Count Berchtold – shooting pheasant unpopular with French – outbreak of enteric – new French uniforms – returns to ruins of Ypres – sees carnage at first hand – wreckage of the Cathedral – criticism of the Belgian authorities – the British soldier as souvenir hunter – sleeps in nuns’ dormitory – direct hit on 1st Life Guards’ billet – terror in the rue des Chiens – a joke gets out of hand – Gen Kavanagh’s anger at surfeit of mail.

VOLUME IV: FEBRUARY 19 – APRIL 14, 1915

A few days’ leave – Lt X’s ‘nervous breakdown’ – a gruesome crossing to Boulogne – ‘felt like death’ – food crisis in Austria – Asquith’s response to German blockade – Neuve Chapelle offensive ‘nearly sensational’ – a missed opportunity – heavy casualties – naval attack on the Dardanelles – effectiveness of the Turkish floating mines – Russians capture Przemysl – the Bishop of London boosts morale – the Prince of Wales and his bearleader – au revoir to Staple – his new billet at Wallon-Cappel chez the Curé’s sister – ‘a most revolting creature of seventy summers’ – visit to St Omer.

VOLUME V: APRIL 15 – MAY 29, 1915

A general ‘one of the culprits’ – Neuve Chapelle more costly than Waterloo – billets doux from the enemy trenches – début of chemical warfare – asphyxiating gas attack overwhelms the French – Germans advance en masse – aviators rescued after plane crash – night march to Vlamertinghe – ‘brave little Belgium’ entirely wrong – gallantry of the Canadians – bad news from Russia – the molten crucible of Ypres – more heavy casualties at Frezenberg Ridge – Italy declares war on Austria – Asquith announces new Coalition Cabinet – Churchill ‘getting a danger to the State’ – 9th Lancers ‘lazy’ about gas respirators – and pay penalty.

VOLUME VI: MAY 30 – JUNE 18, 1915

British losses in May ‘good reading for the Germans’ – would Douglas Haig make a better C-in-C? – Ypres Salient ‘murder pure and simple’ – why preserve this muck heap? – contrast with Nature – how bird life must sneer – worse than pagan barbarism – our men pulverised – sleek deadheads at GHQ – drastic shortage of shells – Cpl Wilkins hit by rifle grenade – visit of Prince Arthur of Connaught – arrival of Kitchener’s Army – more casualty lists – off to England for four days’ leave – visit to the War Office – transfer to Windsor as instructor – Centenary of Waterloo.

Epilogue

Select Bibliography

FOREWORD

Ninety years have passed since the First World War began, amid an upsurge of confidence that it would be over within a few months – over and victorious; a confidence felt by all the warring nations. The fascination with that war has never faded: a fascination derived from our ever-growing knowledge of the scale and nature of the conflict. The diaries of Sir Morgan Crofton are an important addition to the contemporary literature of the war years, presenting many facets of an officer’s experience and emotion.

Sir Morgan Crofton took part in the First Battle of Ypres, a nightmare of a battle in itself, and the prelude to more than three years of trench warfare in the Ypres Salient, the linchpin of the Western Front. His descriptions of what he saw and experienced are graphic and revealing: a powerful testimony to the endurance and perception of a professional soldier, who showed wisdom and sensitivity amid the pressures and turmoil of war. His diary entries are by turn laconic and outspoken. They give a remarkable picture of the rumours and expectations, the daily drudgery and wry humour, the burdens and terrors of trench warfare.

The diarist was well placed to record these scenes. Born in 1879, he entered the Army while Queen Victoria was still on the throne, being gazetted Second Lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers in 1899. That same year he sailed to South Africa, where he was severely wounded during the campaign to relieve Ladysmith. For his war service in South Africa, he was awarded the Queen’s Medal with five clasps. Returning to Britain, he transferred first to the Irish Guards in 1901 and then to the 2nd Life Guards in 1903. In 1902 he had succeeded his brother as 6th Baronet of Mohill, Ireland, a title that goes back to 1801. A Captain in the 2nd Life Guards, he retired in early 1914 and went on the Reserve of Officers. He could look forward to living on his estates in Ireland. There, and in Hampshire where he had his other home, he was a Justice of the Peace. He could not know that his military career would resume so swiftly. When the First World War broke out in August 1914 he was thirty-four years old.

Soldiering was in the Crofton blood. Sir Morgan’s greatgrandfather, also Sir Morgan (the 3rd Baronet), fought at the Battle of Trafalgar as a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy. The 3rd Baronet’s son, Sir Hugh Crofton, fought in the Crimea, first at the Battle of the Alma and then at Inkerman, where he was severely wounded. He was awarded the Legion of Honour and the Order of the Medjidie. Almost a century later, Sir Morgan’s eldest son, Major Morgan George Crofton, served with the 14th Army in Burma in the Second World War, and was twice mentioned in despatches; his youngest son, Edward Morgan Crofton, served for twenty-one years in the Coldstream Guards and his grandson, Henry Morgan Crofton, continues the family tradition as an officer in the same regiment.

The most dramatic and traumatic nine months of Sir Morgan Crofton’s life are those covered by the diaries published here, from October 1914 to June 1915. His wartime service continued until the Armistice. During his service in the Ypres Salient he was twice mentioned in despatches, and was awarded both the Belgian Order of Leopold and the Croix de Guerre. From 1916 to 1918 he served as Provost Marshal in the East African Expeditionary Force, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and the French Legion of Honour. Later in 1918, he returned to the Western Front and saw active service as a Major in the Guards Machine Gun Regiment.

Crofton’s six handwritten volumes of diaries have been impeccably edited by Gavin Roynon, and turned into a single volume. Harrowing in its detail, it casts much important light on one of the severest and most decisive battles of the First World War and its aftermath. His editor’s note, ‘Ypres Then and Now’, is a fascinating survey of a small Belgian town that moved from relative obscurity to centre stage within a few months.

The power of these diaries is enhanced by Gavin Roynon’s dedicated editorial work. He has included biographical notes for many of those who appear in its pages, including the colonel who was most probably the tallest man in the British Army; and he provides historical explanations that place the diary in its wider context; the context of an ever-present, all-devouring war, on several fronts, drawing in and wearing down the manhood of many nations.

Sir Martin Gilbert Honorary Fellow, Merton College, Oxford

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Iam immensely grateful to Edward Crofton for entrusting me with the task of editing the first six volumes of his father’s diaries which gave me three years of fascinating research. It has been a rewarding and enlightening experience. The diaries provide a firsthand record of the traumatic events at Ypres in 1914 and 1915, and show how a group of young cavalry officers faced up to a totally new and devastating form of warfare. As Sir Morgan Crofton kept himself informed about theatres of the war elsewhere, we also have his critical commentaries on such key areas as the Eastern Front, the ill-fated Dardanelles Campaign and the War at Sea.

It has been a privilege to have such a rare primary source at one’s fingertips. I have tinkered as little as possible with the original, merely adding footnotes when a modicum of explanation is required, and endeavouring to avoid retrospective judgements. For the most part the text of this tour de force speaks for itself.

The photograph of the award of the French Croix de Guerre to the town of Ypres and the trio of photos showing the destruction of the medieval Cloth Hall are by Photo Antony of Ypres. Most of the other photographs are original and were taken by Sir Morgan Crofton. He was an expert cartographer and drew the sketch map of the position of the 2nd Life Guards in the trenches at Zillebeke. Sir Martin Gilbert kindly gave permission to reprint his maps of the First Battle of Ypres and of the Ypres Salient from his Routledge Atlas of the First World War and the maps of the Western Front, 1914–15 and the Eastern Front, 1914–16, from his First World War.

The map of ‘The Fight at Klein Zillebeke’ first appeared in The Story of the Household Cavalry by Sir George Arthur. Three maps illustrating the Neuve Chapelle offensive and the area given up as a result of 2nd Ypres are reproduced by kind permission of The Times. I am grateful to A.P. Watt Ltd on behalf of the Lord Tweedsmuir and Jean, Lady Tweedsmuir, for permission to print as an Epilogue the extract from John Buchan’s The King’s Grace, 1910–1935. The ‘Desolation of Ypres’ illustration on the cover, was first published by UPP Paris, and every effort has been made to trace the copyright owner and to attribute the ‘Siege of the Empires’ map, but so far without success. The aerial view of the centre of Ypres first appeared in the Illustrated London News.

Much of the research has been undertaken at the Imperial War Museum, and I am grateful to the team of historians in the Reading Room, who have been a model of courtesy and invariably helpful. I wish to record a special vote of thanks to Roderick Suddaby, Director of Documents, for his invaluable advice and warm encouragement. My neighbour Malcolm Brown willingly drew on his long experience for my benefit and provided informative and witty answers to my questions, however naive.

Christopher Hughes at the Household Cavalry Museum, Windsor, has been immensely patient. He has frequently dug into the archives at my request to trace the service records of individual officers and men in the 2nd Life Guards who served in the Salient. David Woodd kindly researched the polo-playing career of Captain Noel Edwards, who died from gas-poisoning. Michèle Pierron, Librarian of the Musée de l’Armée in Paris, provided exact information about the value of the French franc in 1914 and directed me to various French sources, not readily available in the UK.

I am very grateful to Dominiek Dendooven for his willing guidance during my visits to the Documentation Centre in Ypres. He is the author of Menin Gate – Last Post. Several other kind individuals have helped me along the way. Kerry Bateman, Secretary of the Leicestershire Yeomanry Regimental Association, provided me with a factual report on the heavy casualties suffered by the Regiment at 2nd Ypres. Anne Baker gave me an insight into the early months of the Royal Flying Corps by showing me the archives which belonged to her father, Air Chief Marshal Sir Geoffrey Salmond. Dr Peter Thwaites provided helpful information about the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, where he is Curator of the Archives.

My longstanding friend and mentor, Patrick Wilson, read the text and made several helpful suggestions. Major Douglas Goddard and Margaret Marshall also proof-read sections of the diaries. I am grateful for their painstaking efforts and for pointing out various errors. David Simpson and John Anderson came to the rescue when I was floored by Crofton’s classical allusions. By recalling his father’s experiences in the war, Sir William Gladstone threw helpful light on the shortage of interpreters in August 1914. Jean-Paul Dubois kindly settled any queries I had about France and so further cemented the Entente Cordiale.

My wife, whose father was gassed while serving in France in 1918, has given me great support in this venture and gallantly accompanied me as we tramped far and wide over the battlefields of Ypres. I am equally indebted to my daughter Tessa, who firmly persuaded me to aim high where publishers are concerned – and her advice has borne fruit.

Finally, I must record my gratitude to Janet Easterling. She never complained at my endless updating of footnotes, as fresh information came to light. Without her hard work, good humour and professional approach, this project would never have got off the ground.

Gavin Roynon, Wargrave, August 2004

The Western Front, 1914–15. (First World War, Martin Gilbert)

The Eastern Front, 1914–16. (First World War, Martin Gilbert)

YPRES THEN AND NOW

Editor’s Note

‘I should like us to acquire the whole of the ruins of Ypres . . . A more sacred place for the British race does not exist in the world.’

Winston Churchill, addressing the Imperial War

Graves Commission London, 21 January 1919

Churchill was back in the Government as Secretary of State for War in Lloyd George’s peacetime Coalition. In the highly emotional atmosphere of the early months after the Armistice, there was a strong British and Canadian lobby for the centre of Ypres to be kept in ruins en permanence, as holy ground and a ‘zone of silence’. Happily, by the end of 1919 Churchill was putting his weight firmly behind the construction of the Menin Gate by Sir Reginald Blomfield. This would be dedicated to the huge sacrifices made by the British and Commonwealth Armies, and be the finest Memorial to the Missing.

The atmosphere is still emotional. No visitor can fail to be moved by the poignancy of the ceremony at the Menin Gate. Every evening at 8 p.m. the noisy traffic is diverted, ‘the busy world is hushed’ and silence falls. Eyes are riveted on the thousands of names carved into the walls of soldiers killed in the defence of Ypres between 8 August 1914 and 16 August 1917, who have no known grave. They number almost 55,000. (A further 35,000 British and New Zealand servicemen, who were killed after that date, are commemorated on the Memorial at Tyne Cot.) Then the Last Post is sounded, as it has been – except from 1940 to 1944 – every day since 1 May 1929.

On 31 October 2001, the Duke of Edinburgh and Princess Astrid, daughter of King Albert of the Belgians, attended the 25,000th Last Post, followed by a special service in St Martin’s Cathedral. In 2002, the 75th anniversary of the unveiling of the Menin Gate Memorial by Field Marshal Lord Plumer and the foundation of St George’s Memorial Church, Ypres, were commemorated. This church, in which so many families, regiments and schools have presented memorial plaques, has become a British military shrine. The Friends of St George’s enjoy widespread support and make an annual pilgrimage to the war graves, memorials and battlefields of the Salient. The Chaplain told me that, in 2003, 170,000 people made a pilgrimage to his church – a figure of which many cathedrals might be envious. The historic ties which bind Ypres and Britain together are as strong as ever.

Yet, long before the defining events of the twentieth century, the medieval city of Ypres had stamped itself on the pages of history and enjoyed strong links with England. In the Middle Ages trade was the key to the prosperity of Ypres. For centuries, sheep-farming in medieval Flanders had produced the wool needed in the cloth industry. High-quality Flemish cloth was in demand, and to meet the increasing demand for woollen garments, wool was also imported from England. Thus, the earliest visitors from these shores were neither soldiers nor tourists, but wool merchants. Ypres prospered. Her population rose so rapidly that by 1260 she had 40,000 inhabitants – about ten times that of contemporary Oxford.

In the same year, construction began on the Lakenhalle or Cloth Hall. Reputedly completed in 1304, the massive, but elegant, building, where the wool-trading took place, was a symbol of the wealth and influence of contemporary Ypres. One of the Gothic glories of Europe, 125m long and boasting a superb belfry 70m high, the Cloth Hall stood for more than six centuries. It was to be totally destroyed by incendiary shells on 22 November 1914. Sir Morgan Crofton, who had arrived the previous week at the Front, reports the catastrophe in his diary. He took some photographs of what resembled one of El Greco’s more hellish scenes and gives an eyewitness account of the carnage.

Happily, the medieval builders and craftsmen had no premonition of the horrors which would ultimately destroy St Martin’s Cathedral as well as the Cloth Hall. The Hundred Years’ War was approaching. In 1383, English soldiers were attacking Ypres and experienced the mud of Flanders for the first time. The German nation did not yet exist and Richard II’s foes were the French. The besieging armies, led by the Bishop of Norwich, took the outlying areas, but not the city.

But Ypres suffered in the long term. The Hundred Years’ War caused the import of English wool to cease and the weaving industry declined. Flemish weavers crossed the Channel to find work in East Anglia and Ypres ceased to be the commercial capital of Flanders. Spanish rule was established in 1555, and the province became part of the Spanish Netherlands. Sectarian religious wars were rife. Not for the last time, Ypres saw a massacre of the innocents when zealous Protestant ‘reformers’ slaughtered Roman Catholics – and vice versa.

Spanish control yielded to French, and Louis XIV instructed his great military engineer Vauban to build a ring of defensive walls around Ypres, with bastions for the artillery. Centuries later, the British soldier found these walls an invaluable backdrop as he sheltered behind them in his dugout. The core of Vauban’s defensive works, including the Lille Gate, survived the four years of battering they received from German shells. Today, visitors should doff their hats to him as they enjoy the fine ramparts walk overlooking the canal.

Only in 1830 did Belgium become independent, and a kingdom in 1831. Aware that Belgium would make an admirable springboard for the invasion of England, the British Government negotiated the Treaty of London, which guaranteed Belgium’s neutral status. Signed in 1839 by the major European powers, no treaty has cost Britain more dearly. It was to honour this famous – or infamous – ‘scrap of paper’ that Great Britain, under Asquith’s premiership, declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914.

Before the First World War Ypres had enjoyed relative obscurity, but now it leapt into undesirable prominence. By the end of the third week of August, Brussels had fallen, the British Expeditionary Force was falling back alongside her French Allies, and German troops reached the little town of Meaux, about 20 miles from Paris. Von Moltke faltered, and, following the crucial Allied victory at the Marne, both sides sent troops rapidly northwards in an attempt to outflank each other. They clashed in Flanders, and the First Battle of Ypres, fought from 19 October to 22 November, reaped a terrible harvest of casualties. The war of movement was over.

It is during this battle that Capt Sir Morgan Crofton arrives at Ypres to join his regiment, the 2nd Life Guards. Pitchforked at once into the trenches, he jots down his experiences in standardissue Army notebooks and provides the reader with a personal and powerful account of his experiences. From the six handwritten volumes of his ‘Anglo-German War Diary’, we gain a clear insight not only into the grim privations men suffered, but also the camaraderie and close friendships formed. ‘Bored in billets, terrified in trenches.’

Nor does Crofton hesitate to be controversial. ‘Poor little Belgium’, the Christmas Truce (‘this is WAR, Bloody War, not a mothers’ meeting’), the state in which the French ‘always’ leave their trenches, the breakthrough at Neuve Chapelle that proved such a damp squib but cost ‘nearly double the loss of the British contingent at Waterloo’, Churchill’s demotion in the Cabinet, the dire British shortage of shells – all are exposed by Crofton’s pen.

But it is the decision after the Second Battle of Ypres to hold on to the Ypres Salient at all costs which most arouses the diarist’s ire. Years later, in his History of the First World War, Liddell Hart regrets that Haig did not ‘fulfil his idea of withdrawing to the straighter and stronger line along the canal through Ypres. It would have saved cost and simplified defence.’

Long before the historians had their say – and before the war is even one year old – Crofton, who is on the scene, cuts starkly to the heart of the matter:

The Salient at Ypres is simply an inferno. It is not war, but murder pure and simple. The massacre which has been going on here since April 22 is not realised at home. From May 1–16, we were losing men at the rate of 1,000 a night. Why we don’t give it up now, God alone knows. As a strategic or tactical point Ypres is worthless. . . . The town is a mere heap of rubble, cinders and rubbish. . . . We cannot conceive why the Salient is not straightened and given up. Hence why keep Ypres to impress people?

These words were written on 5 June 1915. When Crofton confided this blistering attack on the Higher Command to his diary he did not know there would be a Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). Nor could he have predicted that, by the end of the war, more than 200,000 British and Imperial troops would lie dead in 170 different military cemeteries, all contained within the few muddy square miles of ‘the Immortal Salient’.

‘For your tomorrow, we gave our today.’ When we look – through Sir Morgan Crofton’s eyes as well as through our own – at the plethora of names on the Menin Gate, we are left with the sickening conviction that thousands of them need never have been there.

Gavin Roynon

AFTERNOTE

In May 2003, Edward Crofton and I visited Ypres and many of the surrounding villages where Sir Morgan Crofton had billeted the troops of the 2nd Life Guards from 1914 to 1915.

During our visit, in a moving little ceremony, Edward officially returned to the Dean, Jaak Houwen, the fine leaded fragment of the East Window and the key of the West Door of the Cathedral, which his father had saved from the rubble eighty-eight years earlier (see diary entry for 8 February 1915, p. 162–5).

The Kaiser’s ‘Explanation.’

Biographical Note on Lieutenant Colonel Sir Morgan Crofton, Bt DSO

As Sir Martin Gilbert so ably describes in his Foreword, we are a military family. Our forebears and descendants have served the forces of the Crown for over two hundred years. In addition to those of my ancestors to whom Sir Martin specifically refers, my father’s father and his two brothers were also commissioned, and this military tradition has continued into the twenty-first century.

My father did not have a particularly auspicious start in life. Born the younger son of the youngest son of the previous generation, his father died when he was three years old, leaving him and his elder brother to be brought up by their mother. Times were difficult and the two boys spent their early years commuting between their maternal grandfather in Colchester Garrison, and their paternal grandmother (the widow of Colonel Hugh Crofton) at Marchwood in the New Forest. While his brother attended Eton, my father followed members of his mother’s family to Rugby. His two surviving Crofton uncles had also both died early, and so when his brother died aged twenty-four he was on his own.

In 1897 he was appointed Second Lieutenant in the Militia Forces, and in 1898 he was successful as an Infantry candidate at the literary examination for entry to RMC Sandhurst.* The following year he was awarded a Commission in the Army.

From the outset of his military career he pursued a particular interest in military history, and his knowledge of the subject over ensuing years was profound. He became a notable contributor to military journals, and was an acknowledged authority on Napoleon and the Waterloo Campaign. The publication in 1912 of his booklet on the role of the Household Cavalry Brigade at Waterloo earned him many plaudits. This was followed in the same year by an article on The Relative Values of Certain Present Time European Agreements which was reviewed as being remarkable for its political insight and accurate diagnosis of the European situation. He rightly underlined the dangers of a Europe in which the five great empires were polarised into two armed camps by the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente. This insight may explain the commentaries on Central European and Near Eastern campaigns, which he includes in his diaries.

My father enjoyed a distinguished career after the Armistice. Following retirement from the Regular Army in 1919, he served in 1922 as Commandant of the Schools and Depot of the Ulster Special Constabulary. Throughout this period, he continued his military writing and developed his skills as a cartographer. He compiled the highly detailed and intricate campaign maps for Liaison 1914, written by his old friend Sir Edward Spears. He was High Sheriff of Hampshire, the county in which he lived, in 1925/6 and a Gold Staff Officer at the Coronation of His Majesty King George VI. For a time in the 1930s he was a ‘Blue Button’* with a firm of stockbrokers in the City of London. In 1942 he was appointed Commanding Officer of the 28th (Bay) Battalion of the Hampshire Home Guard, remaining in command until the Home Guard was disbanded in December 1944. He died in 1958, ten days after his seventy-ninth birthday.

Divorce had necessitated his retirement from the Army in 1914, and so it was perhaps fortuitous that events unfolded as they did later on that year, enabling him to return to the Colours. Thus his diaries were born, and they represent a vivid and candid account of his daily experiences on the Western Front in the early months of the First World War. As with others of his generation who were fortunate enough to survive, the horrors of this conflict left an indelible impression on him. He never held back from saying what he thought and, as the reader will soon discover, political correctness was not in his make-up. I therefore believe that the genuine and heartfelt opinions which he expresses accurately portray the acute sense of frustration and despair which became so prevalent on the Western Front during those four terrible years.

Edward Crofton

* The Royal Military College Sandhurst at Camberley, Surrey. In 1938 the decision had been taken to amalgamate with the Royal Military Academy Woolwich. However, the advent of war in 1939 caused the decision to be shelved until 1946, when planning for the new Academy recommenced. The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst was officially opened in the following year and remains in this form to the present day.

* The term ‘Blue Button’ enabled the individual to obtain share prices from jobbers on the floor of the Stock Exchange. However, it did not authorise trading in shares. Holders wore a blue button to denote the practice, which ceased in 1986 with the advent of the ‘Big Bang’ in the City of London.

VOLUME I

OCTOBER 27 – DECEMBER 3, 1914

TUESDAY OCTOBER 27

Captain Sir Morgan Crofton, Bt 2nd Life Guards

Herewith a copy of telegram received from War Office. Please arrange to hand over your duties as Area Staff Officer, South Eastern Area, as soon as possible to Captain F.W. Ramsden (late Coldstream Guards) 5, Upper Brook Street, W. (Telephone Mayfair 3717).

As soon as you have handed over, please report to this office and then proceed to Windsor to join Depot 2nd Life Guards.

Horse Guards,

G.Windsor Clive

Whitehall,

Major

S.W.

General Staff, London District

27 October 1914

I returned to my flat from the Marlborough Club, where I had gone after finishing my daily round in the South Eastern area, reaching home about 6.30 pm, and then found the above communication from the London District Office enclosing a War Office wire, directing me to rejoin my Regiment at Windsor for duty.

This was because of the heavy losses in officers which the 2nd Life Guards were sustaining in the desperate attempts of the Germans to reach the sea at Calais which had resolved themselves into a series of terrific struggles round Ypres. This memo was very welcome, for it had for a long time been very irksome to be at home in a comfortable staff billet, when the Regiment was going through such strenuous times in Flanders.

The Regiment had left Ludgershall Camp on October 6th, being railed to Southampton for Ostend and Zeebrugge, where it disembarked early on October 8th, and came under the orders of General Sir Henry Rawlinson* commanding the newly formed IV Corps.

The Regiment in conjunction with the 1st Life Guards and the Blues** forms the 7th Cavalry Brigade under Brigadier General Kavanagh. This Brigade, and the 6th Brigade consisting of 10th Hussars, Royal Dragoons and 3rd Dragoon Guards, forms the 3rd Cavalry Division, and is under the command of Major General Byng.†

I was thankful to give up the Area Staff job, although it had been useful and very essential. I had to survey, and lay down the Defence plan for every vulnerable point in the South Eastern Area of London. These included power stations, gas works, bonded stoves, purifying stations, sewage works, the Charing Cross railway bridge (a ticklish job, with trains coming from every direction, every few minutes), and the Penge and Chislehurst Tunnels.

I had a good liaison with every police station in my area. These jobs keep me very occupied every day of the week from 9 am to dark. The tunnels were tricky to inspect, as were also the Vickers Works at Erith. However, this was now finished and I could now return to my Regiment on service. I therefore got onto Ramsden and arranged with him to hand over all maps, plans, notes and details of all sorts connected with the South Eastern Area at 10 o’clock the following day.

* Rawlinson led IV Corps throughout 1915 and was then promoted to command the newly formed Fourth Army for the Somme Offensive. A strong advocate of beginning the Battle of the Somme with limited attacks, he was overruled by Haig. After the Armistice, he served in Northern Russia and then became Commanderin-Chief, India in 1920. He died in 1925.

** Royal Horse Guards.

† Later FM Viscount Byng of Vimy. He was the inspired commander of the Canadian Corps, who captured Vimy Ridge in April 1917. His special link with the Canadians was recognised by his appointment as Governor-General of Canada in 1921. A fine portrait by Philip de Laszlo hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

WEDNESDAY OCTOBER 28

Handed over to Ramsden as arranged, and reported (11 am) myself to GOC London District, Sir Francis Lloyd, who was very kind and friendly, and thanked me for my work.

Packed and left for Windsor by the 3.40 pm train from Paddington.

Reported at 5 pm to the OC 2nd Life Guards Reserve Regiment, Colonel Oswald Ames. (The tallest man in the British Army,*a dear man but not very quick or enterprising.) Trooper Hosegood told off to me as Batman, for the time being.

THURSDAY OCTOBER 29

Went to London after lunch to buy kit and get ready for the Front. Got 2 pairs of ankle boots, a British Warm and a pack saddle trunk. Wired Fuller, my groom at Woodside, to bring up my charger and saddlery to Windsor. Returned to Windsor 6 pm.

There were a lot of strange faces amongst the officers at Windsor. Some had been there weeks, and did not seem to me to be particularly anxious to leave the comparative peace and security of the Cavalry Barracks.** Ames did not have enough ‘Ginger’, he was too kind and friendly to push some of these people out. I suppose this sort of thing always happens in war. All the Regular officers were abroad, either with the Regiment or on Staff Duties, and a stream of individuals arrived from all sources, of all kinds, some ex-officers retired from various Regiments. Some Planters, many Civilians from every Profession.

Most of these were quite excellent, keen, brave and most anxious to get out and do a job of fighting. Some had come hurrying home from South America, Canada, East and South Africa. The real offenders, who should have known better, were nearly all retired ex-officers who had been called up from obscurity and soft lives.

However, it wasn’t my affair. It was Ames’s funeral. I made it quite clear that I insisted on going out with the next reinforcements.

*Probably true, as his height was 6ft 8½in! Ames had retired in 1906, but rejoined the 2nd Life Guards in August 1914.

** Renamed Combermere Barracks by the 1st Life Guards in 1900 after Lord Combermere (Colonel of 1st LG until 1865). But the 2nd Life Guards and the Blues refused to use the new name! It is still the home of the Household Cavalry in Windsor. The original barracks, completed in 1804, were built on a plot of land given by Eton College. In earlier centuries, the site housed a leper hospital.

FRIDAY OCTOBER 30

To London again to finish my kit buying.

SATURDAY OCTOBER 31

Finished equipping myself. Was inoculated against enteric* at 9.30 pm.

Fuller and Horse arrived from Marchwood, with all kit, so I am now ready for all eventualities.

SUNDAY NOVEMBER 1

Stayed in all day and wrote letters. Inoculation began to work, felt very cheap!

MONDAY NOVEMBER 2

Got a day’s leave to go to Woodside** to settle up matters there. Arranged to close the house for the ‘Duration’. Returned to London at 7 pm. Reached Windsor at 8.

TUESDAY NOVEMBER 3

Went to London to try on my British Warm, make a few 11th hour purchases. Got hair cut!

* Enteric fever or typhoid.

** His home at Marchwood near Southampton in the New Forest. It was destroyed by a bomb in December 1940.

WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 4

Went to London to see my Lawyer. Had tea with my Mother at Buckingham Gate. Returned Windsor 7 pm.

It struck me in London that there was a profound air everywhere of anxiety as to the Battle for the Channel Ports.* Now approaching its climax before Ypres. I felt more and more restless at not being in it. The casualties seem very very heavy.** From what we hear the Regiment seems to be in the thick of it day and night, and we are expecting that substantial reinforcements will soon be called for.

The Composite Regiment has been disbanded, and its component parts have been drafted to the 3 Regiments in the 7th Cavalry Brigade, which will help to fill the depleted Cadres. Anyhow we shall soon hear something definite.

About 8.30 during Dinner the Orderly Room Corporal appeared with an Order, just received, from GOC London District that 5 officers were to proceed as soon as possible to the Front, 2 to the Blues, 2 to the 1st Life Guards and 1 to the 2nd. This is my chance!! A few words with Ames clinched it.

THURSDAY NOVEMBER 5

Sent for to report to the Orderly Room at 8.30. Told to pack instantly and leave for the Front that evening. Ward-Price† (the brother of the Daily Mail Special Correspondent) and I were ordered to join the Blues. Packed and left Windsor by the 12.05 train.

Reported to Colonel Holford, 1st Life Guards, at Knightsbridge Barracks at 2.30. We arranged to leave for Southampton at 9.50 pm.

Wrote letters until 3 o’clock. Sent some wires and said goodbye all round. Went to my Mother’s flat and stayed with her until 9.15 pm, when I left for Waterloo to catch the train, picking up my luggage at the Marlborough Club en route. At the station I met Mathey (an ex-diamond expert) and Goodliffe, late 17th Lancers, both of whom were joining the 1st Life Guards.* Holford came to see us off, and Lady Holford gave me some letters for her son, Stewart Menzies, the Adjutant of the 2nd Life Guards.

We reached Southampton Docks at midnight – an exciting day.

* The British Expeditionary Force relied on the Channel ports of Boulogne, Calais and Dunkirk for reinforcements of men and munitions. The fall of Ypres would have left the route to the coast wide open.

** This was true. See 15 November.

† Severely wounded on 13 May 1915, 2/Lt L.S. Ward-Price was later transferred to the 2nd Life Guards. He volunteered for the Royal Flying Corps, but was killed in an aerial action over France in January 1918. His fate was discovered from a report in a German newspaper.

FRIDAY NOVEMBER 6

Midnight. Having arrived at Southampton Docks Station, we then had a long walk in the dark to where our ship was berthed. We received our tickets and warrants from the Transport office, and went to board the Lydia about 1.15 am. Berths were allotted to us. Mine was 155, but as all four were put into it we objected and succeeded in getting a larger one into which Ward-Price and I went. Slept well until 9 am.** Cabin like a monkey house.

Had a bad and expensive breakfast at 9.30. Beautiful fine hot day, the sea like glass. Humorous Canadians issued us tins of Bully Beef and a loaf of Bread at 1 pm to each of us as rations for 2 days! Nowhere to carry this simple food so made it up into a parcel, which on landing fell into the sea.

Reached Le Havre at 2, and after threading through Minefields came alongside the quay at 2.45.

Several very large steamers came in with us, with the 8th Infantry Division on board. Landed about 3.15, and after considerable difficulty secured a cab, and having piled in our kit and luggage drove off into the town to report our arrival.

Reached the office of the Base Commandant about 4 pm. Found a mob there of recently landed officers milling round an unfortunate staff officer of the Gordon Highlanders† who was half suffocated. Joined the mob and helped the process! His piteous appeals of ‘It’s getting too hot here, gentlemen, please stand back’ produced little effect. Room finally cleared of all but myself.

Received orders to leave for Rouen by the 5.50 train. Went off and got lunch with Ward-Price, who got very muddled over 2 glasses of Chablis.

Greatly struck by the number of women in the streets in deep mourning.* Watched the 1st Battalion Hertfordshire Regiment march through the town en route for the Rest Camp outside. Very strong and fine Battalion – grand fellows.

At 5.15 we drove to the station after picking up Goodliffe and Mathey. Given a Chrysanthemum by a small girl in the street, and shook hands with several unknown persons in various stages of cleanliness! Put our luggage consisting of 4 valises, 4 boxes, 8 saddles and 6 various into a first class compartment, and got into the next one ourselves. We were told that we should reach Rouen in 3 hours. As a matter of fact it took 6, arriving there at midnight.

Reported our arrival to the Station Staff Officer, a seedy individual with a hacking cough. Told to go into the Town for the night, and report at the Remount Depot at 8.45 in the morning.

We collected our kits and stepped over several officers’ valises which were spread out on the platform, in which their Batmen were soundly sleeping. We then sallied out into the town to find a Hotel, followed by half the population of the place!

* Capt H.W.P. Mathey and Capt H.M.S. Goodliffe.

** Other ranks had a rougher passage. Tpr George Frend, aged nineteen, and his brother Will crossed to Le Havre on the same night in a small ship used for transporting horses. ‘We dossed down in the cattle pens almost in darkness, but before we got down to it, Will and I, we saw a notice about our heads – “This Scupper may be used as a Urinal only”. From a document lent by Col Nigel Frend.

† The 2nd Gordon Highlanders had suffered severely at Zandvoorde on 30 October. Along with the 1st Grenadier Guards, 2nd Scots Guards and 2nd Border Regiment, they formed part of the 7th Division, described by Cyril Falls as ‘In infantry, possibly the best division in the British Army.’ See his Life of a Regiment – The Gordon Highlanders in the First War, 1958, p. 13.

SATURDAY NOVEMBER 7

12.30 am. Found Hôtel de Paris near River Quay. Hall crowded with various officers more or less all in varying stages of alcoholism. Rum looking lot! Our arrival hailed with considerable levity. The Patron, an individual of villainous aspect, introduced himself to us. We decided to stay here pending Orders. To Bed, after a supper of Beer, Omelettes and semi-raw Beef, at 2.

8.45 am. We taxi to the Remount Depot which was 3½ miles away, out near the Race Course, and report ourselves. We were told to ‘Stand By’ and to report every day at 8.45 and 3 until we get Orders to move.*

Decide to live in Camp so as to be near Orders. Return to the Hôtel de Paris at 12 to collect kit. Lunch at a Restaurant near the Cathedral, and return to Camp at 3.30. No tents, but are allowed to use the Mess Marquee to sleep in. Return to dine in Rouen at the Hôtel de la Poste, where we got a bath. Back to our Marquee and bed at 11.30.

* Belgian and French women bereaved as a result of the war wore deep black: ‘widows’ weeds’ were a common sight in France up to and including the 1950s.

SUNDAY NOVEMBER 8

Damp, cold and misty day. Got tent and put it up. Ward-Price and I in one, Goodliffe and Mathey in the other. Also got servants. Ward from 17th Lancers as Batman, Young, 2nd Life Guards, as Groom.

No orders. Told that they may be expected any day.

Lunched and dined at Hôtel de la Poste, where I bumped into a certain MacCaw, 3rd Hussars, with whom I had once been on a course at Aldershot. He was now acting as DAAG,** and as such was responsible for the posting of Officers as they joined the Depot. I explained quite definitely that I did not want to go to the RHG but to my own Regiment, 2nd Life Guards. He said that he would see what he could do. So I pushed in at once for Transfer.

After dinner, sort out kit and repack valise, etc. for the Front. Return to tent, very damp, to bed at 11.

MONDAY NOVEMBER 9

The battle for Ypres had been raging since 19 October. It was vital to get the horses to the troops in Flanders as soon as possible. Many horses were frantic after the sea crossing and liable to lash out. Here Crofton skates fairly lightly over the ‘strenuous efforts’ needed to choose and equip his horses.

Trooper George Frend was at the same Remount Depot outside Rouen and witnessed the pandemonium. ‘Thousands of horses had recently arrived from Canada, Australia and the Argentine. There was no kit to groom them with; there were no bridles to put on them, but they had to be taken to water two miles away twice a day; each man riding one and leading two with nothing but head collars and ropes. Horses and men went spare all over the country and to my knowledge, at least two men were killed.’

Getting the horses to the right station and on to the right train was the next hazard. Crofton’s horses get lost en route, but despite being hauled over the coals by a choleric general, he keeps his cool . . .

Awakened at 6.30 by an excited Orderly who ordered us all to pack at once, collect Horses and Saddlery, and get to the Station. Scene of great confusion followed. Got packed and succeeded in choosing hurriedly from line of 500 Horses, 2 Chargers and a Pack Horse. The Saddles fitted badly, and we couldn’t get Bridles on. However, after strenuous efforts we succeeded in getting ready around 10.30.

Start off for Train. Baggage waggon late, so leave Servant to pack on it and follow at once. Groom rides 2nd Charger and loads Pack Horse. All now start off riding to the Station. Great difficulty in finding Station as there are four in Rouen, and we are not told which one to go to.