Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

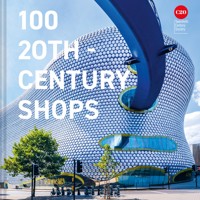

A showcase of Britain's most architecturally significant shops throughout the twentieth century and beyond. 100 20th-Century Shops is a fascinating insight into the heritage of Britain's changing high street and the diverse architectural styles of the 20th century. Entries in this book showcase 100 often instantly recognisable shops from across the country, from throughout the 20th century and stretching into the 21st, capturing the changing architectural styles of our beloved and rapidly disappearing retail environment. As the UK's retail landscape faces an existential crisis, now is an appropriate time to review and celebrate the architecture of our high streets. From Tudor-revival department stores and futuristic supermarkets to Art Deco shop fronts and post-war Festival style markets, the 100 shops featured here evoke a variety of design styles and traces the history and evolution of our cherished high street. The book also contains essays by respected writers Elain Harwood, Lynn Pearson, Matthew Whitfield, Kathryn A. Morrison and Bronwen Edwards on the design, development and decline of the high street over the last 100 years within a social and political context. This compelling book provides a glimpse into the wonderful shops that Britain has to offer and is a must-have for all fans of design history, architecture and retail.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 176

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Introduction

Catherine Croft

1916–1929

Markets, Arcades, Precincts and Shopping Centres

Elain Harwood

1930–1949

The Co-operative Movement and its Stores

Lynn Pearson

1950–1959

Department Stores

Matthew Whitfield

1960–1969

Multiples and Chain Stores

Kathryn A. Morrison

1970–1979

The Twentieth Century Boutique

Bronwen Edwards

1980 onwards

Acknowledgements

Further reading

Picture credits

Index

INTRODUCTION

What will be the future of shopping? Have we passed peak in-real-life shopping? Or will retailers and developers do ever more to lure us out to buy in person. What more can they dream up as a way to convince us that shopping is beyond a necessity but rather ‘an experience’, and an enjoyable social activity we can’t do without? In 2022 I was a judge for the World Architecture Festival’s Shopping award, and our winner was an enormous new complex just completed in Chengdu, China, which wraps shopping units around a completely fabricated ‘ecological park featuring mountain and river scenery’. Other large-scale entries featured an Olympic-standard skateboard park, a rooftop Ferris wheel and a massive yellow Pikachu Pokémon figure. But alongside these was a suburban development in Melbourne, Australia, inspired by Queensgate Market, Huddersfield (1968–70 by the J. Seymour Harris Partnership) and an exquisitely detailed Japanese pavilion, which fused a spectacle shop with a bakery and a play area. Globally shopping seems to be alive and well, but perhaps significantly, there were no UK entries shortlisted.

The double impact of easy internet ordering, and the Covid pandemic, seems to have sucked some of the vitality out of the UK high street. The options offered by online browsing make even the most comprehensive department store look parochial. The knowing exclusivity of the ‘curated’ collections of exclusive boutiques have been at least partially supplanted by the social media posts of online influencers. Repeated doom-mongering, mass sell-offs (including that of the Debenhams chain) and bankruptcies, prompted the Twentieth Century Society both to launch our department stores campaign and to compile this book. We wanted to celebrate a world that seemed uniquely threatened, and to explore ways in which these buildings could be imaginatively repurposed. Before we go to press, the austerity crisis makes the future of many of these amazing buildings seem bleaker yet. But our belief that shops are important, not just for their architectural quality, but for the social histories they embody, has been strengthened by the enthusiasm of our members and supporters for the topic, and the extent of media interest.

Department stores in particular have been studied for their role in the emancipation of women, offering both an alternative employment to ‘service’, and a public venue in which women could be respectably visible and meet away from the scrutiny of home. But many of us also relate to our local department store extremely personally: it is the place we remember going to be fitted for our first shoes or bras, where we compiled wedding lists and purchased school uniforms, tried out double beds and then pushchairs, all of which speak to events that act as markers of major life milestones, both joyous and possibly traumatic. One of my earliest memories is of being lost among the rails in Bentalls in Kingston. The planning inquiry into the future of the Marks &; Spencer flagship building on Oxford Street captured the public imagination and put the environmental arguments in favour of adapting and reusing shopping buildings centre stage, albeit with an assumption that their higher floors might well be reasonably and more profitably switched to alternative uses, such as office or residential conversion. Here was a ‘national treasure’, a company with a much-voiced commitment to sustainability, set on sending a solid and reusable building to oblivion. It seemed to be an act that combined both a hypocritical disregard of those environmental credentials, and a deliberate lack of regard for its own popular heritage.

Marks & Spencer, Oxford Street, London by Trehearne and Norman with W.A. Lewis, 1929–30

Denys Lasdun’s Peter Robinson, The Strand, London, 1959, demolished 1996

I don’t really mourn the loss of shopping as a fun leisure activity. Maybe I was too scarred by the excruciating, sweaty embarrassment of Saturday afternoons wriggling on the floor of Top Shop and Miss Selfridge’s claustrophobic communal changing rooms, trying to squeeze into skin-tight jeans in the pre-Lyra early 1980s. But I do remember the excitement of Eva Jiřičná’s shops for Joseph, of their high-tech steel and glass, which felt unbelievably glamorous, and it was at the Katharine Hamnett Knightsbridge store, with its catwalk entrance way, that I first remember being aware of the work of Norman Foster. Shops allow us to appreciate architecture up close, to see and handle details and materials, and to participate in a highly choreographed spatial experience first-hand. It’s condensed architecture, with added graphics and bespoke furniture, designed to make an immediate impact on us and affect our mood and actions.

One clear message from this kaleidoscopic survey of some of the best and most fascinating shops of the twentieth century, is that today’s rapid evolution and transformation of the high street is far from unprecedented. In many cases, we are featuring not free-standing new buildings, but design-led fit-outs, intended as little more than transient stage sets. Some major works by leading architects had remarkably short lives. For instance, Denys Lasdun’s Peter Robinson on The Strand opened in 1959 and was demolished in 1996, none of Wells Coates’ work for Cryséde or Cresta survives, nor that of Patrick Gwynne for Freeman Hardy & Willis. The fact that Burton menswear stores often had billiard halls upstairs has been largely forgotten, as has the provision of lending libraries in branches of Boots, although both were deeply embedded in our culture – for instance in the film Brief Encounter, the heroine Laura’s weekly routine includes a regular trip to Boots to change her books and the practice was top of John Betjeman’s ironic list of ‘what our Nation stands for’ in his 1940 poem ‘In Westminster Abbey’.

Will automated tills and more sophisticated methods of scanning and billing continue to automate the shopping experience? Or will we return to more intimate and personal encounters in terms of both buildings and personnel? All of the examples brought together here show that shops have long been designed to do more than just facilitate the exchanging of goods. In researching her entry on the Croydon IKEA (page 226) Katrina Navickas found that a somewhat cynical blogger had compared a trip to IKEA to an outing to another converted power station: ‘It’s very similar to a trip to Tate Modern (3.6 million visitors per year). Looking. Shuffling. Self-awareness. Hunger. Flirting. Looking. Imagining. Not quite enjoying. Smugness. Not quite understanding.’ Perhaps that quote gives some clue as to where we have gone wrong, and what we need to challenge. If they are to survive, our shops need to support us having more fun, and more social interaction, and to use design to make that happen.

Catherine Croft

c20society.org.uk

Freeman, Hardy & Willis, Catford, south London by Patrick Gwynne, 1953, remodelled as a Curtess shoe shop in 1955

Burdon House

Location: 1–4 Burdon Road, Sunderland

Designed by: William Bell and Arthur Pollard, North Eastern Railway Architect’s Department

Opened: 1916

Listed: Grade II

The North Eastern Railway, responsible for lines from York into the Scottish Borders, had a reputation for innovation, sound economics and good design. Hence the building of prestigious shops to support offices for its staff in the heart of the city centre; the railway runs directly behind. It was also the first railway company to appoint a full-time salaried architect, in 1854, with William Bell occupying the post from 1877 to 1914. He adopted Queen Anne and classical styles, continued by his successor Arthur Pollard.

Designed in 1914, the style of Burdon House was classical, executed in local ashlar with giant pilasters. Perhaps it was ownership by the railway that allowed the scheme to be completed in wartime. The shopfronts survive unusually well, with a double row of small top lights over the main shopfront, in rusticated surrounds. The bowed corner unit has long been a bar, while student accommodation now occupies the other floors.

Elain Harwood

Heal’s

Location: Tottenham Court Road, London

Designed by: Cecil Brewer, in partnership with A. Dunbar Smith

Opened: 1916

Listed: Grade II*

Ambrose Heal transformed his family’s bed-manufacturing business into makers and retailers of Arts and Crafts furnishings of a wholesome, high-minded kind. Rebuilding premises at 196 Tottenham Court Road, he employed his cousin, Cecil Brewer, with A. Dunbar Smith, in 1912–16, the latter the date on the building. Heal and Brewer visited the Deutsche Werkbund exhibition in Cologne in 1914, and the latter confessed himself ‘all agog with German things afloat in my head’. The steel-framed, stone-clad façade completed under wartime conditions, is an early example of ‘stripped classicism’ with decorative panels by Joseph Armitage. It set a standard for structural clarity and decorative restraint. The recessed arcade with projecting blinds on special bronze brackets is a notable feature. The shop was extended to the south by five bays in 1936–8 by Edward Maufe, whose wife Prudence worked for Heal’s, and to the north in 1961–2 by Fitzroy Robinson & Partners in a modern yet respectful idiom.

Alan Powers

Brights, later House of Fraser

Location: Old Christchurch Road, Bournemouth

Designed by: Reynolds and Tomlins (attributed)

Opened: c.1920

Listed: Grade II

Brights Stores was founded by Frederick Bright in 1871 in The Arcade, next door to its current building in Old Christchurch Road. Around 1905, Brights enlarged their store with an innovative new iron-framed extension, accommodating shops and showrooms with a restaurant and offices above. A decade or so later, the store, then Bright and Colston, was upgraded and its nineteenth-century north and east elevations remodelled in fashionable Art Deco style. This work has been attributed to the Bournemouth-based architects who designed the streamlined Dolcis store on the corner about 15 years later. The Old Christchurch Road elevation is clad in cream tiles, supplied by Carter and Co. of Poole, forming pilasters and arches which frame the windows and define the bays, while terracotta panels, decorated with sunbursts in blue and brown faience, express the floors of the steel-framed structure behind. Early twentieth-century staircases, cast-iron columns and decorative plasterwork survive inside.

Coco Whitaker

Piccadilly Chambers

Location: 1, 3 and 5 Piccadilly, York

Designed by: Walter Brierley with James Rutherford

Opened: 1921

Listed: Grade II

Walter Brierley, nicknamed the Lutyens of the North, designed over 300 buildings across Yorkshire and beyond throughout his 40-year career at the turn of the century. The profound impact that his prolific output had on the built fabric of York has cemented Brierley as a quintessential author of the city, bringing Wrenaissance and later neo-Georgian design to its historic streetscape.

Piccadilly Chambers was one of Brierley’s last works and sits at the south end of Parliament Street, the city’s main market until 1955. The building – a bank and offices originally including shops – is firmly neo-Georgian, of warm red brick above a chaste ground floor of local stone. However, it features a delightful angled corner wholly of ashlar with giant Corinthian pilasters across the upper floors. Though opened in 1921, the rainwater heads are dated 1915, a clear example of delays caused by the First World War.

Finn Walsh

Former Woolworths, Preston

Location: 30–31 Fishergate, Preston

Designed by: William Priddle

Opened: 1923

Frank Woolworth opened his first store in America in 1879. The first British store opened in Liverpool in 1909, followed in 1910 by a second in Fishergate, Preston. This relocated to its current site in 1923, trading until the collapse of Woolworths in 2008.

Woolworths quickly developed a distinctive, albeit largely traditional style for their shops and employed their own architects, William Priddle serving from 1919 or earlier until his death in 1932. Like Burton, Woolworths used Priddle and his assistants to brand an expanding chain. His elaborate white faience frontage has eight two-storey columns topped by vaguely Egyptian Moderne capital decorations: 1922 was the year Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered, but the motifs were used into the 1930s. The central vertical panel has a tall oriel window. White faience, probably by Shaws of Darwen, was a practical self-cleaning surface for Preston’s rainy, sooty weather. The building now houses a branch of Next.

Aidan Turner-Bishop

Kennedy’s Sausages

Location: 305 Walworth Road, London

Opened: c.1923

Listed: Grade II

Kennedy’s sold sausages for cooking at home, and pies for consumption straight away. When the firm ceased trading in 2007 after nearly 140 years, the Twentieth Century Society put all their surviving premises across south London forward for listing. This branch is one of several with an original timber shopfront and grey granite stallriser, and four stained glass transom lights in an Art Deco sunburst design. The distinctive fascia is of polished glass and has a makers’ mark reading ‘W. Piggot Ltd (brilliant process)’; letters of V-section were impressed into copper sheets with steel dies and then covered in glass.

The interior is clad in coloured tiles, green beneath the timber dado rail and primrose yellow up to the picture rail, and some original fittings remain. Since listing, several businesses have occupied the site, but it is currently empty. We hope that newly available grant funding will make proper restoration feasible.

Catherine Croft

Reliance Arcade, Market Row and Granville Arcade

Location: Brixton, London

Designed by: R. S. Andrews and J. Peascod (Market Row); Alfred and Vincent Burr (Granville Arcade, now Brixton Village)

Opened: 1925–37

Listed: Grade II

These three market buildings thread through the centre of Brixton, crowded with small shops and stalls. They were twice proposed for total demolition, in the 1960s and again in the early 2000s, when the Twentieth Century Society applied for listing.

The subsequent list description notes the significance of the Egyptian frontage inspired by the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922, interiors featuring black vitrolite, and use of both concrete and steel truss roof structures to let in plenty of light, but the application was initially turned down. Only after a campaign backed by the local MP emphasised the historic significance of the markets to the Afro-Caribbean community was the complex listed: ‘The successful adoption of the markets is the clearest architectural manifestation of the major wave of immigration that had such an important impact on the cultural and social landscape of post-war Britain, and is thus a site with considerable historical resonance.’

Catherine Croft

Vigo House, Empire House, Westmorland House and New Gallery

Location: 115–131 Regent Street, London

Designed by: Sir John Burnet and Partners

Opened: 1925

Listed: Grade II

The rebuilding of John Nash’s Regent Street by the Crown Estates, mainly carried out in the 1920s, was widely condemned for its poor taste, but the block on the west side just north of the Quadrant, incorporating the New Gallery as a cinema, designed in 1920–25, has usually been judged a success. Commissioned by a former Edinburgh patron, R. W. Forsyth, proprietor of a successful menswear business, John Burnet relied increasingly on Thomas Tait, who was able to modulate the classicism of his senior partner towards plainer forms. The Times grouped it among designs showing ‘steady progress in designing for masonry and brickwork in well-proportioned masses, instead of relying on the trimmings of style’, while for Howard Robertson, the block had ‘one of the finest fronts in Regent Street’, although he was less happy with the curved corners and their heavy domes. Sculpture was contributed by Sir William Reid Dick.

Alan Powers

Liberty’s

Location: Regent Street and Great Marlborough Street, London

Designed by: Edwin T. Hall and E. Stanley Hall

Opened: 1926

Listed: Grade II

Designed in 1914 but held back for over ten years, Edwin T. Hall and his son, E. Stanley Hall, produced an unusual Portland stone façade on Regent Street with a concave upper story bearing a narrative frieze and stone figures appearing to look over the parapet. For the larger, side-street block they had greater freedom. Within its original shop, Liberty’s (founded in 1875) had already adopted a ‘Tudor feeling’ and the early 1920s marked a high point of enthusiasm for this look. ‘The Tudor period is the most genuinely English period’ wrote Ivor Stewart-Liberty in 1924, on completion of his half-timbered shop commissioned from the same architects. Oak from old warships reaffirmed the nostalgia and provided a dark background for displaying the company’s famous fabrics. A jumbled rather than unified street view disguised the successful modern business. The company is still trading under the original name in the Tudor building.

Alan Powers

Markets, Arcades, Precincts and Shopping Centres

Markets date back to Roman times, controlled by royal charters from the Middle Ages. These were street markets, and it was only in the seventeenth century that some form of cover was introduced, initially for fish and meat. Substantial indoor markets date only from the nineteenth century. Some towns erected specialist retail markets for foodstuffs and dry goods, though most separated only meat and fish – the most essential for reasons of hygiene and smell. Sheffield’s historic castle area saw the development of fish and meat markets (rebuilt in 1928–30), the dry goods Norfolk Market, the Castlefolds wholesale market and the open-air Sheaf Market, a flea market held on Tuesdays and Saturdays – every level of small trader was thus catered for within a small area. Nottingham’s historic open-air market was swept out of the Market Square into new covered markets opened in 1928 on a slum clearance site in Huntingdon Street, leaving the old square to be reconfigured as a formal setting for the new Council House. In another project that also involved slum clearance, the Corporation of the City of London took over Spitalfields Market in 1920 and doubled its extent by 1928. Though the 1897 buildings survive, those of the 1920s have been demolished, a pattern seen across the country.

Markets assumed a symbolic importance in the war, for they continued trading after conventional shops had been bombed out and provided a lifeline for local economies; even Marks & Spencer took a market stall after Plymouth city centre was destroyed. In consequence they assumed an important position economically and as architectural features when bomb-damaged cities came to be rebuilt. In other towns and cities, the large, prime sites occupied by market buildings made them targets for redevelopment as part of new shopping precincts. New markets provided architectural drama in new town centres at Hartlepool and Huddersfield, unlike at Nottingham, where the replacement for the Central Market was a nondescript adjunct to the Victoria Centre opened in 1972. The best post-war markets were virtuoso pieces of engineering, and survivals include arched concrete shells at Plymouth (1959), umbrella-like shells at Huddersfield (1968–70), cantilevered ‘gull-wing’ roofs at Bury, built in 1968–71, and cranked cantilevers at Hartlepool (1967–71). The markets at Plymouth, Coventry and Huddersfield are listed, but others of equal bravado have been destroyed, as at Sheffield, Blackburn and Accrington. Only Swansea Market, opened in 1961, made a feature of an arched steel roof, a token of support for local industry. All had to combine a broad span, only Huddersfield having columns, with large areas of glazing to bring natural light to the heart of these enclosed buildings, all set in the centre of an urban block surrounded by small shops and cafés.

Similar lighting problems on a smaller scale faced the builders of shopping arcades, single malls of specialist luxury shops that created specialist retail space while also linking two or more major shopping streets. They grew out of colonnaded shopping pavements and exchanges, and first appeared in Paris. The first in Britain was the Royal Opera Arcade, in London, opened in 1821. Arcades assumed a civic grandeur when the concept was translated to Italy, and the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II built in Milan between 1865 and 1877 inspired buildings as diverse as the Letchworth Arcade of 1922 (after Ebenezer Howard included a shopping galleria or ‘Crystal Palace’ in his vision of a garden city), Exchange Buildings of 1924–9 in Nottingham and Milton Keynes Shopping Building of 1975–9.

Queensgate Market, Huddersfield, J Seymour Harris Partnership, 1968–70

More arcades were built in the interwar period than has hitherto been recognised, and details often survive well, such as glazed roofs and terrazzo floorings; covenants and leasehold terms ensure a high survival rate even for shopfronts. The Harris Arcade of 1929–31 in Reading, incorporating an earlier motor showroom, has shop fronts of metal and timber painted to resemble bronze with Art Deco details. A more rough-shod but colourful complex survives at Brixton, south London, where the Reliance Arcade of 1925, Market Row of 1928 and the former Granville Arcade of 1937 were threaded through and behind existing buildings. From its origins as a working-class market, Brixton Market became the centre of small businesses for the local Black community and is being repurposed again for street food sellers. These examples are among only a handful of interwar arcades to be listed.