Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

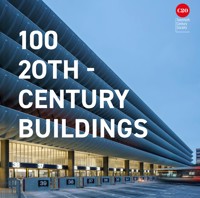

A stylish celebration of some of the greatest buildings in Britain, from the 20th century and beyond, by the country's leading organisation for the protection of 20th century architecture. This fascinating book showcases 100 standout buildings from 1914 onwards, representing the broad variety of 20th century British architecture. The structures celebrated in this book include the Royal Festival Hall, the Hepworth Gallery, Preston Bus Station, Battersea Power Station, the Barbican Estate, the Aquatics Centre and many more. The glorious photography in 100 20th Century Buildings is accompanied by insightful text from a range of expert architectural writers and enthusiasts including Alan Powers, Owen Hatherley and Rowan Moore, along with several longer essays on different aspects of the 20th-century built environment: the late Gavin Stamp on the inter-war decades, the much missed Elain Harwood on post-war architecture and Timothy Brittain-Catlin on postmodernism. From factories to art galleries, churches to health centres, office blocks to individual private dwellings, this book provides a captivating overview of the 20th century built environment.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 183

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1002OTH -CENTURYBUILDINGS

The TwentiethCentury Society

Edited by Susannah Charlton withElain Harwood

CONTENTS

ForewordHugh Pearman

IntroductionCatherine Croft

100 Years Timeline

1914–1929

The Inter-war DecadesGavin Stamp

1930–1944

1945–1969

Post-war Architecture Elain Harwood

1970–1989

PostmodernismTimothy Brittain-Catlin

1990–2013

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Picture Credits

Index

FOREWORD

The best thing about presenting a year-by-year account of a century’s buildings is that you can demonstrate the full breadth of architectural styles and movements over the period. It is nearly always the buildings of the relatively recent past that are most at risk – 30 years, say, is a dangerous age, when public opinion may still reject a given style, a building may require considerable refitting, and the wrecking ball can loom. But it is also the age when, in the normal run of things, the best buildings can be listed, which offers some protection.

But over the course of a century, you can look more widely. So it is with the period covered by the Twentieth Century Society. Our remit begins in 1914, the effective end of the ‘long 19th century’. Hence this book, first published in 2014. And hence the fact that, while a lot of our work concerns the finest post-Second World War buildings in the broadly modernist sphere, the longer timescale reveals everything from neo-classical (starting with the lushly Edwardian rear galleries of the British Museum) via the full-on Gothic Revival of Bristol University’s Wills Memorial Building, the Art Deco factories of London’s Great West Road, inter-war mock-Tudor, the golden age of streamline-moderne cinemas, and, harbinger of modernism, the glass curtain-walled Boots D10 building in Nottingham.

The traditionalist strand, of course, continued: look at the first post-war building listing, Sir Albert Richardson’s 1959 Bracken House for the Financial Times. ‘A living breathing Edwardian among the Teddy Boys’ as Alan Powers puts it. With its Michael and Patty Hopkins’ ingeniously bay-windowed 1990s central expansion, it is an object lesson in enlightened adaptation and re-use – and now pleasingly has the ‘pink ’un’ back in it.

There have been losses. Some were lost before the first edition of this book. Others have gone since, such as the 1999 Sainsbury’s Eco-store in Greenwich which was cynically demolished in 2016 for banal retail sheds. Some others such as Vauxhall Bus Station are under threat at the time of writing. But there are also plenty of victories to report, including a Grade I listing for the British Library and a raft of postmodern listings, from Stirling/Wilford’s No. 1 Poultry to John Outram’s pumping station on the Isle of Dogs.

Battersea Power Station, a 30-year saga, is finally safe, if visually overloaded with new development. And I hope Lloyd’s of London (Grade I) will long continue to stimulate debate, as it did between the writers of the first edition.

Hugh Pearman, Chairman, C20 Society

INTRODUCTION

This selection of 100 buildings has been put together by the C20 Society, from nominations made by our members and supporters, to mark the centenary of the period under our remit – buildings completed from 1914 onwards. There are plenty of buildings here that are really well known, but quite a few that aren’t. The purpose of the selection was not to nominate the ‘best’ or the ‘most representative’ building constructed in each year (that would be a very tricky and specious task) but to gather together some favourites, and show a diverse group that would demonstrate just how fantastic and varied the architecture of the last 100 years has been. Inevitably lots have been left out. My particular regrets include no Camden housing, and no Bill Mitchell sculptures. Some of the selected buildings are ones that would not exist today if the C20 Society had not campaigned to save them; a few, alas, have been demolished already. Together they make the most compelling argument possible for the ongoing necessity of the C20 Society’s work. There is still much work to be done to ensure the long-term survival of the best architecture and design of our period and, while the popularity of some of these examples is now well established, the merits of many remain contentious.

Many conservation groups focused on 20th-century architecture are very partisan – that is, they look exclusively at one style or type of building. For instance, there are many Art Deco societies, most notably in the USA – in Miami and Los Angeles, cities which were extensively developed in the 1920s and 1930s – and in Napier, New Zealand, which was rebuilt after an earthquake in 1931. DoCoMoMo, which has 59 chapters in many countries around the world, is exclusively interested in the architectural heritage of the Modern Movement – essentially functionalist architecture born of the machine age.

In contrast, the C20 Society has always been interested in all 20th-century buildings, regardless of the style they followed (including those which claimed to have no style, but be the pure product of objective problem-solving). As you will see, some in this selection were heavily influenced by what was being constructed abroad and extensively photographed and published in the architectural press here. Others draw only on British precedents, and could not have been designed anywhere else. We are aware that our own tastes have changed, as our knowledge has grown. There is no one person’s selection here; not everyone agrees all of the time. Our former Chairman Gavin Stamp always regretted the loss of Sir Edwin Cooper’s Lloyd’s building (see page 185), and never warmed to the Richard Rogers replacement, now widely regarded as a high tech masterpiece and listed at Grade I – at the request of the C20 Society. But we were able to agree that the latter was historically significant, and keep talking to one another.

Interior of Farnley Hey, West Yorkshire, by Peter Womersley, 1955 (see page 120).

Alexandra Road Estate, London, by Camden Architect’s Department, 1972–8.

The Society regularly researches buildings and proposes them for listing. Recommendations are passed to English Heritage, but the final decision-maker is a politician, in the Department of Culture Media and Sport – we’ve challenged the objectivity of several holders of the post. By law, we are consulted by every local authority planning department in England every time a building owner makes an application for permission to demolish or substantially change a listed building.

My first major case as Director of the C20 Society was Greenside (see page 78), a classic listed Modern Movement house, demolished by its owner who didn’t like it, and was not convinced it could be successfully refurbished. I had assumed that this type of house, now iconic and already recognised as a very rare example of pioneering design from a key period of innovation, would not be at major risk. However, it proved very vulnerable because it was a relatively small and dilapidated property, on quite a large plot, in a prestigious and unique location beside Wentworth Golf Course.

A larger new house on the site would have been worth many millions. Although ultimately the owner was convicted of unlawful demolition (a sentence which gave him a criminal record), for the C20 Society it was a frustrating demonstration of the weakness of our heritage protection system. The fine imposed was far less than the profit the owner looked set to make from rebuilding. Although we were subsequently successful in arguing that no new building could be erected, as the site had been returned to being a vacant plot in the green belt, the building was still gone forever. It made me realise that the Society had to concentrate not just on winning legal battles, but on doing our best to get as many people as possible to share our enthusiasm, and see the potential for keeping, maintaining and continuing to use and enjoy 20th-century buildings.

Louis Hellman cartoon from the Architect’s Journal, 21 July 2005, on the fate of Greenside.

To that end we regularly run visits and tours, including trips to many of the buildings featured in this book. We have organised conferences to further academic research, and published books and magazines on lots of previously largely unrecognised architects and little-known buildings. Right now we are still trying to explain that Brutalist buildings aren’t meant to be brutal, and that although postmodernism may be out of fashion, the best examples will come to be appreciated again in due course, if they manage to survive. We are also filling in the gaps with the architecture of earlier decades, searching out examples that are perhaps less flashy or obvious than some of their contemporaries – the ones that weren’t published in the magazines when they were new, and were less accessible to the dominant media hub of London.

We know that one reason people feel wary of taking on 20th-century buildings is that they are not sure how to set about repairing them, or how to sensitively upgrade them to meet modern expectations. We know that underfloor heating has frequently failed and that, while single glazing may have been a reasonable choice when electricity was cheap and plentiful and no one had heard of global warming, it is hard to live with now. Friends still giggle when I tell them I’m off to teach my annual course on the Conservation of Historic Concrete, but it is not an oxymoron. For many years ‘concrete cancer’ was feared an insurmountable problem, and now concerns over the safety of RAAC (Reinforced Autoclaved Aerated Concrete) components are quite reasonably intense. Some buildings will no doubt require major interventions, however, most concrete buildings are very robust, and can be repaired much as stone buildings can. Concrete can age and weather beautifully, developing a patina – though I accept that it doesn’t always manage it. The myth that many of us wanted to believe, that buildings could be made from materials that would need no maintenance, was just that: a myth. Looking back at what architects were actually saying, it’s hard to work out where the myth actually came from – many were scrupulous about specifying the necessity for simple housekeeping (clearing gutters, painting windows), which we know are equally essential with buildings of earlier periods. And of course, some elements of building fabric have needed replacing, but then what’s the fundamental difference between re-laying an asphalt roof and re-thatching a cottage?

Some 20th-century buildings required enormous amounts of traditional craft skills. In some cases this is very apparent, but in others the care which went into working out details is forgotten; top quality concrete relies on very good carpentry skills to make formwork, and many buildings which have a factory aesthetic are in fact bespoke. Having said that, if factory-made elements are used, there is no good reason why we should consider them fundamentally less worth saving than hand-crafted ones. Much can be learned about the world at any date from the materials used in the buildings erected then, whether facts about transport and trade links, the availability or lack of labour, or the priorities of one function over another.

Much of this evidence can be lost in overly drastic makeovers, and ‘retrofit’ projects which all too often retain little beyond a building’s structural frame. While buildings of earlier centuries are generally ‘restored to their former splendour’, with much effort made to keep as much historic fabric as possible and research and replicate materials, 20th-century buildings are often totally reinvented. At times this is a sensible thing to do, but some schemes go too far and, although billed as conservation projects, they actually preserve little of what made the original structure special in the first place. The recent redevelopment of Park Hill flats in Sheffield is a classic example of this. Images of the site once it had been stripped out show just how much went in the skip. Now a kind of fetishistic false history has been created in the flats by exposing the bare concrete frame, once clothed with modest timber architraves and plaster finishes. The Design Museum’s move to the old Commonwealth Institute building in Kensington raises similar issues. Again, little more than a skeleton has been kept: just the structural components of the hyperbolic paraboloid roof remain. What will be the long-term verdict on what’s been termed architect John Pawson’s 21st-century ‘rebirth’ of a building that arguably did not need major surgery? The C20 Society would have preferred a solution that was more compatible with the original concept of a building whose interior provided a particularly mesmerising experience.

These buildings don’t need melodramatic make-overs – they don’t need the equivalent of false eyelashes, a fake tan and 6-inch heels. They need a little gentle tidying up, new services and sympathetic owners who will take pleasure and pride in them. Unlike classic cars, classic architecture can’t stay in the garage until it is sunny outside and everything is freshly polished. While an unfashionable work of art can be relegated to the basement store to be appreciated again at a future date, a demolished building cannot be rebuilt. The C20 Society exists to ensure good examples do survive, even when commercial pressure and market forces might favour redevelopment. This is a book of photographs but I hope it is a book that will make readers want to go and see buildings for real. Architecture impacts on all the senses, and is part of all our lives. The best 20th-century buildings enrich us all.

Catherine Croft

Director, C20 Society

www.c20society.org.uk

Hockley Circus, Birmingham, by William Mitchell, 1968.

The Commonwealth Institute, London, by RMJM (Grade II*), 1962, before the site was radically developed as housing and the Design Museum.

100 Years Timeline

Social and Political History and International Landmarks

Year

UK Architecture and Planning

First World War begins

1914

C20 Society remit begins

1916–20

Experiments with new materials and techniques, like prefabrication and Crittall windows, prompted by inflation having pushed up the cost of building materials

First World War ends

1918

1919

Housing (or Addison) Act promises ‘Homes for Heroes’

Erection of temporary Cenotaph in Whitehall (see page 46)

1924

Royal Fine Art Commission created to look into questions of public amenity or artistic importance

Empire Exhibition, Wembley

Mechanical vibration of concrete

L’Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris – title gives us the term Art Deco, popularised by Bevis Hillier in the late 1960s

1925

New Ways, Northampton, by Peter Behrens for W. J. Bassett-Lowke is the first Modern Movement house in Britain

General Strike

1926

1927

Vers une Architecture by Le Corbusier published in English as Towards a New Architecture

The first ‘talkies’ seen in Britain; Decline and Fall by Evelyn Waugh published

1928

Big new super cinemas start to be built

Wall Street Crash

1929

High and Over, Amersham, the first truly modern house in the UK

Stockholm Exhibition – a model for the Festival of Britain

1930

Empire State Building, New York

1931

Charles Holden’s Sudbury Town is the first modern London Underground station

Royal Corinthian Yacht Club, Burnham-on-Crouch, by Joseph Emberton

1932

Hoover Factory, Great West Road (see Firestone Factory page 58);Boots D10 factory opens (see page 66)

Hitler comes to power in Germany; Jewish emigration starts; Unemployment in the UK rises to 2.5 million

1933

1934

Penguin Pool, London Zoo, by Lubetkin and Tecton and Lawn Road Flats (see page 73)

The Modern House by F. R. S. Yorke published

1935

Highpoint One by Lubetkin and Tecton; De La Warr Pavilion (see page 74)

Jarrow March; Constitutional crisis as Edward VIIIabdicates the throne in order to marry Mrs Simpson

1936

Crystal Palace burns down

1937

Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer leave for USA as little work in UK

Glasgow Empire Exhibition

1938

Pillar to Post by Osbert Lancaster published

Second World War declared 3 September

1939

1–3 Willow Road, Hampstead, by Ernő Goldfinger

1940–1

Introduction of building licences imposes controls on raw materials (to 1954)

First Mies van der Rohe skyscrapers in Chicago

1942

Beveridge report on a social security system to challenge the five giants of ‘Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness’

1943

Exhibitions on Swedish and American housing propose prefab housing

6 June: Normandy Landings: D-Day

1944

Fine Building by Maxwell Fry published

Education Act makes all schooling free and establishes the 11 plus, and grammar, secondary modern and technical schools

Town and Country Planning Act enables local authorities to compulsorily acquire sites for redevelopment and introduces the listing of historic buildings

Second Word War ends; Labour, under Clement Attlee, wins

the General Election with its first ever majority

1945

1946

Programme to build housing, schools and factories to cope with bomb damage and baby boom

Powell and Moya win competition for Churchill Gardens flats in Pimlico, London

New Towns Act: Stevenage the first New Town – 13 more follow by 1950; Hertfordshire programme of prefabricated schools begins

Coal shortages, electricity failures and a run on the pound

1947

New controls on building introduced by Stafford Cripps; Restrictions on private house building rigorously enforced; Town and Country Planning Act, the major post-war legislation covering redevelopment, compensation, green belts and the listing of buildings

Nationalisation of coal industry (Act of 1946)

Frederick Gibberd appointed architect of Harlow

Start of National Health Service in May

1948

Royal Festival Hall commissioned as centrepiece for the Festival of Britain (see page 104)

Nationalisation of electricity industry

First national Code of Practice for reinforced concrete in the UK (CP114)

Equitable Savings and Loan Association in Portland, Oregon, is the first curtain-wall building

Rebuilding of bombed cities, notably Plymouth and Coventry begins

Iron and steel nationalised by second Labour government

1950

Frederick Gibberd wins limited competition for Heathrow Airport

Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House in Falls River, near Chicago

1951

Festival of Britain takes place

The first of Pevsner’s Buildings of England series is published

Conservatives return to power; they encourage more, yet cheaper, schools and housing

Gibberd’s The Lawn, in Harlow, is Britain’s first ten-storey ‘point’ block

Queen Elizabeth II accedes to the throne on the death of George VI

1952

Golden Lane housing competition for the City of London won by Geoffry Powell of Chamberlin, Powell and Bon

London’s last trams run; iron and steel denationalised

Town Development Act encourages the expansion of towns like Swindon

The Coronation causes a demand for television sets

1953

Changes in housing policy encourage slum clearance, putting pressure on city centres

1954

End of building licensing in November

Opening of the London County Council’s (LCC) first large comprehensive school at Kidbrooke, London

ITV launched, and the film Rock Around the Clock promotes new youth culture

1955

Reyner Banham’s essay ‘The New Brutalism’ published in the Architectural Review

Waiting for Godot opens in Britain, Look Back in Anger is premièred

1956

LCC eases restrictions on tall buildings in London

The Suez Crisis delays several building projects

Span’s first scheme Parkleys (Richmond borders) opens, a landmark in low-cost housing

Start of Vietnam War (1956–75)

This is Tomorrow exhibition

White Paper on technical education creates Colleges of Advanced Technology

Macmillan becomes Prime Minister, and says Britons ‘have never had it so good’

1957

Housing Act controls rents and evictions after Rachman scandal. Many large landowners prefer to sell up to local authorities for redevelopment

Nottinghamshire County Council opens its first prefabricated (CLASP) school, designed to ride subsidence caused by mining

The first publicly funded theatre opens in Coventry

Sussex University College founded, the first of a programme of new universities around the country

Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey first performed

1958

Arne Jacobsen appointed architect for St Catherine’s College, Oxford; Competition for Churchill College, Cambridge launched

Preston Bypass, Britain’s first stretch of motorway, opened

M1opens from Watford to Crick

1959

Schemes for tall towers include Millbank Tower, Centre Point and the Economist Group

Penguin Books found not guilty of obscenity in the Lady Chatterley’s Lover trial

1960

St Paul’s Bow Common by Maguire and Murray is first centrally-planned post-war church

The first birth-control pill

Opening of Keeling House, London and Park Hill, Sheffield: high-density flats on slum clearance sites

New universities approved for York and Norwich; Chamberlin, Powell and Bon masterplan for Leeds University

The Beatles perform for the first time at the Cavern Club, Liverpool

1961

First proposals for the Brunswick Centre by Leslie Martin and Patrick Hodgkinson, as a medium-rise, mixed-use development, after tall towers are rejected (see page 226)

John Darbourne, aged 23, wins competition for Lillington Gardens in Pimlico with a medium-rise brick scheme

Boom in building means shortages of building material and labour, and government encourages prefabrication

Cuban Missile Crisis

1962

Basil Spence’s Coventry Cathedral opens, with Britten’s ‘War Requiem’

Hard winter delays building and increases unemployment

1962

Centre Point by Richard Seifert and Partners, and Millbank Tower by Ronald Ward and Partners completed, dramatically changing London’s skyline

Profumo scandal; John F. Kennedy assassinated 22 November

1963

Completion of Leicester University Engineering Tower by Stirling and Gowan (started 1959)

Robbins Report on technical education, recommending the widening of higher education and provision of more courses in applied science and technology

Buchanan report, Traffic in Towns, is a best-seller: it recommends the organisation of towns into precincts separated by improved roads, and the segregation of pedestrians and vehicles

Labour win narrow election victory; Harold Wilson government elected on a modernisation agenda

1964

Ministry of Housing and Local Government looks at low-rise, high-density housing with scheme at West Ham

South East regional plan estimates another 1,250,000 people will need to be housed over the next 20 years, and proposes three new cities in the region

George Brown imposes a ban on new office buildings in London