11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

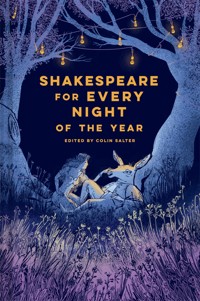

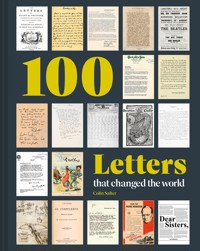

An intriguing collection of the most inspiring and powerful letters of all time. The written word has the power to inspire, astonish and entertain, as this collection of 100 letters that changed history will show. Ordered chronologically, the letters range from ink-inscribed tablets that vividly describe life in the Roman Empire to remarkable last wills and testaments, passionate outpourings of love and despair, and succinct notes with deadly consequences. Entries include: • A job application from Leonardo da Vinci, with barely a mention of his artistic talents. • Henry VIII's love letters to Anne Boleyn, which eventually led to the dissolution of the monasteries. • The scrawled note that brought about Oscar Wilde's downfall. • Emile Zola's 'J'accuse!' open letter, in support of an alleged spy and against anti-Semitism. • Beatrix Potter's correspondence with a friend's son that introduced the character of Peter Rabbit. • A last letter from the Titanic. • Nelson Mandela's ultimatum to the South African president. A stunning new edition with an elegant new cover, this fascinating book is perfect both for reading cover-to-cover and dipping into to discover the delights within.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 424

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

100 LETTERS

that changed the world

A montage of many of the letters included in the book.

100 LETTERS

that changed the world

Colin Salter

Contents

Introduction

c. 346 BC

The Spartans respond to a letter from Philip II of Macedon

44 BC

Caesar’s murderers correspond to work out their next move

c. 50 AD

St. Paul guides the principles of Christianity through his letters

c. 100 AD

Tablets reveal details of life at the edge of the Roman Empire

c. 107 AD

Pliny the Younger describes the eruption at Pompeii to Tacitus

c. 450 AD

Romano Britons plead for help from Rome as the empire fails

1215

English barons try to flex their legal muscle after Magna Carta

1429

Joan of Arc tells Henry VI she has God on her side

c. 1480

Leonardo da Vinci sets out his skills to the Duke of Milan

1485

Henry VII writes to English nobles asking for their support

1493

Columbus explains his discoveries to the king of Spain

1521

Martin Luther tells his friend,‘Let your sins be strong’

1528

Henry VIII writes a love letter to Anne Boleyn

1542

De las Casas exposes Spain’s atrocities in the New World

1554

Elizabeth I writes to Bloody Mary, begging for her life

1586

Babington’s plot is revealed in coded letters to Mary, Queen of Scots

1588

Philip II of Spain insists the Armada press on and attack England

1605

Lord Monteagle gets a carefully worded warning …

1610

Galileo explains the first sighting of the moons of Jupiter

1660

Charles II reassures Parliament that they will be in control

1688

The English nobility make Prince William of Orange an offer

1773

Ben Franklin’s stolen mail reveals a political scandal

1776

Abigail Adams tells husband John to ‘Remember the Ladies’

1777

George Washington employs his first spy in the Revolutionary War

1787

Jefferson advises his nephew to question the existence of God

1791

Mozart writes to his wife as he struggles to finish Requiem

1791

Maria Reynolds tells Alexander Hamilton her husband has found out

1793

Thomas Jefferson wants a French botanist to explore the northwest

1793

After murdering Marat in his bath, Charlotte Corday writes in despair

1805

On the eve of battle, Lord Nelson sends a message to his fleet

1812

Napoleon informs Alexander I that France and Russia are at war

1830

As machines replace farm labour, Captain Swing issues a threat

1831

Charles Darwin gets an offer to become the naturalist on a surveying ship

1840

The first postage stamp transforms the sending of letters

1844

Friedrich ‘Fred’ Engels begins a lifelong correspondence with Karl ‘Moor’ Marx

1845

Baudelaire writes a suicide letter to his mistress … and lives

1861

Major Robert Anderson reports he has surrendered Fort Sumter

1861

On the eve of battle, Sullivan Ballou writes to his wife, Sarah

1862

Abraham Lincoln sends General McClellan an ultimatum

1862

Abraham Lincoln spells out his Civil War priorities to Horace Greeley

1863

William Banting wants the world to know how he lost weight

1864

General Sherman reminds the citizens of Atlanta that war is hell

1880

Vincent van Gogh writes an emotional letter to his brother Theo

1888

A Chicago Methodist training school launches a money-spinner

1890

George Washington Williams sends a furious open letter to King Leopold II of Belgium

1892

Alexander Graham Bell writes to Helen Keller’s teacher Anne Sullivan

1893

Beatrix Potter illustrates a letter to cheer up five-year-old Noel Moore

1894

Pierre Curie sends Maria a letter begging her to come back and study

1897

Oscar Wilde writes a letter to Lord Alfred Douglas from Reading Gaol

1898

Writer Émile Zola accuses the French army of an anti-Semitic conspiracy

1903

Orville and Wilbur Wright send news to their father, Bishop Milton Wright

1907

John Muir lobbies Teddy Roosevelt about incursions into Yosemite

1909

Lewis Wickes Hine reports to the National Child Labor Committee

1912

Captain Scott: ‘We have been to the Pole and we shall die like gentlemen’

1912

The very final letter from the Titanic that was never sent

1917

Zimmermann offers Mexico the return of Texas, Arizona and New Mexico

1917

Lord Stamfordham suggests a new name for the British royal family

1917

Siegfried Sassoon sends an open letter to The Times

1919

Adolf Hitler’s first anti-Semitic writing, a letter sent to Adolf Gemlich

1935

Master spy Guy Burgess gets a reference to join the BBC

1939

Eleanor Roosevelt takes a stand against the Daughters of the American Revolution

1939

Albert Einstein and Leo Szilárd warn President Franklin D. Roosevelt

1939

Mussolini congratulates Hitler on his pact with Russia

1940

Winston Churchill pens a blunt response to his private secretary

1941

Roosevelt sends Churchill the poem that moved Abraham Lincoln

1941

Virginia Woolf writes a final letter to husband Leonard

1941

Winston Churchill gets an urgent request from the codebreakers

1941

Telegram reports that Pearl Harbor is under attack

1943

General Nye sends General Alexander a misleading letter … by submarine

1943

Oppenheimer gets the go-ahead to research an atomic bomb

1943

J. Edgar Hoover receives ‘The Anonymous Letter’

1943

The shipwrecked JFK sends a vital message with two Solomon Islanders

1948

Marshal Tito warns Stalin to stop sending assassination squads

1952

Lillian Hellman sends a letter and a message to Senator McCarthy

1953

William Borden identifies J. Robert Oppenheimer as a Soviet spy

1958

Jackie Robinson tells Eisenhower his people are tired of waiting

1960

Wallace Stegner composes a paean to the American wilderness

1961

Nelson Mandela sends the South African prime minister an ultimatum

1962

Decca sends a rejection letter to Beatles manager Brian Epstein

1962

On the brink of war, Khrushchev sends a conciliatory letter to Kennedy

1962

Kennedy replies to Khrushchev as tensions ease

1963

Martin Luther King, Jr. sends a letter from Birmingham City Jail

1963

Profumo’s resignation puts an end to British politics’ biggest sex scandal

1965

Che Guevara tells Fidel Castro he wants to continue the fight

1973

James McCord writes to Judge John Sirica after the Watergate trial

1976

Ronald Wayne sells his 10 per cent share in Apple for $800

1976

Bill Gates writes an open letter to computer hobbyists who are ripping off his software

1991

Michael Schumacher crosses out ‘the’ and becomes World Champion

1999

Boris Yeltsin admits running Russia was tougher than he expected

2001

Sherron Watkins sends a letter criticising Enron’s dubious accounting

2003

Dr David Kelly admits he was the source for critical BBC report

2005

Bobby Henderson asks Kansas to acknowledge the Spaghetti Monster

2010

Chelsea Manning writes to Wikileaks with a data dump

2010

Astronauts lament America’s lack of a space delivery system

2013

Pussy Riot singer trades philosophies with Slavoj Žižek

2013

Edward Snowden has a shocking revelation for the German press

2013

The whistleblowers appeal to future whistleblowers

2017

Letters – the next investment boom to follow art?

2018

Women in the entertainment industry demand change

2019

Greta Thunberg reads a letter to the Indian prime minister

Addendum: Helen Keller writes to Alexander Graham Bell

Index

Introduction

Ever since the spoken word evolved into its written form, letters have played a significant part in history. Some have played a pivotal role and shaped the fate of nations, others have recorded momentous events, while many have simply given us an insight into what it was like to live in times past.

Letters from the ill-fated transatlantic liner RMS Titanic have often turned up at auctions and commanded high prices. Ironically RMS is short for Royal Mail Ship.

Edinburgh,Scotland2019

Dear Reader,

I thought it was a good time to write you a short letter. This book is all about letters from history – letters from figures great and small. Within these pages you will find private letters, public letters and open letters; letters to be obeyed, disobedient letters; first letters, chain letters, last letters, lost letters, telegrams, and a couple of important messages sent on the eve of battle.

They may or may not have changed history, but all have historical significance. Pliny the Younger’s eyewitness account of the 79 AD eruptions of Vesuvius didn’t change history, but his letters to Tacitus describing the event have provided archaeologists with a vivid insight for the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum. His uncle, Pliny the Elder, died during the catastrophe, and his report was so accurate that his name is remembered by modern vulcanologists when they speak of Plinian eruptions.

Other letters are much more intimate in their contents. Here you will find an example of Henry VIII’s courtly letters to the latest love of his life, Anne Boleyn; letters that curiously ended up in the Vatican in Rome. They also include Pierre Curie’s first attempt to make his partnership with his future wife Maria (later, Marie) more than merely a scientific collaboration. After her spell as a student in Paris she returned home to her native Poland to continue her work there. He wrote her an impassioned letter and she came back to Paris.

Marie Curie is not the only scientist to have received a letter which ultimately led to world-changing scientific breakthroughs. The routine letter which advised a young Charles Darwin that there was a place as Naturalist on the surveying vessel HMS Beagle was an ordinary piece of correspondence, but as a result of that five-year trip he developed his theory of Natural Selection. There are letters from technological pioneers, including one from Galileo in 1609 describing the moons of Jupiter, which he had just seen through his telescope, and the telegram from the Wright Brothers immediately after their historic first flight. Leonardo da Vinci’s 1480 CV and covering letter to the Duke of Milan includes career highlights you won’t find on any other CV.

Elsewhere you can read the letter that gave J. Robert Oppenheimer the go-ahead to develop the atomic bomb, which is interesting for the fact that it doesn’t mention the atomic bomb. If that was Oppenheimer’s beginning, his end was the letter from William Borden which accused him of being a Communist spy. And the consequences of his work – nuclear weapons – nearly brought the world to extinction, averted only by the correspondence between Nikita Khrushchev and President Kennedy to resolve the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

Oppenheimer wasn’t a spy; but espionage is a theme that runs through much of the book. You can read about the scandal of letters secretly passed to Ben Franklin which revealed the true opinion of Britain’s governor of the Massachusetts colony; and you can read the letter from George Washington commissioning America’s first spy ring. The book also contains the letter suggesting that one of Britain’s most notorious spies, Guy Burgess, had passed through his Communism phase, as if it were a childhood illness.

Britain’s own spy network was well established by the sixteenth century, when it uncovered letters of collusion between Mary, Queen of Scots and a group plotting to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I of England. There’s also the story of the Bletchley Park codebreakers who wrote directly to Winston Churchill begging for more resources to help break the Germans’ Enigma code; work which would eventually turn the tide in favour of the Allies in World War II.

One of the most critical letters from history, sent by Russian leader Nikita Khrushchev to John F. Kennedy during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

Wars are history’s ugly landmarks – the milestones through time which change the lives of millions. The first letter in the book is an impertinent reply to an ancient Greek army demanding the surrender of its enemy Sparta. Elsewhere there are letters between allies (for example Roosevelt and Churchill, Hitler and Mussolini) and enemies (Napoleon of France declaring war on Alexander I of Russia), and between winners and losers. General Sherman’s letter to the citizens of Atlanta during the Civil War is a very human acknowledgment of the necessary horrors of war, while the telegram reporting the bombing of Pearl Harbor is stark in its brevity.

There are more personal accounts of war, too. Sullivan Ballou’s loving letter to his wife Sarah was found among his possessions after his death at the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861. Poet Siegfried Sassoon’s outspoken letter to his commanding officer during World War I may have helped him to survive the conflict. John F. Kennedy’s celebrated letter-on-a-coconut certainly saved his life when he was stranded on a Pacific Island after his patrol boat was sunk.

Modern espionage is as likely to be corporate or political as military. James McCord admitted the extent of his involvement in the Watergate Affair in a confessional letter which blew the scandal wide open. The whistleblower is a modern phenomenon and this book includes letters from those who exposed malpractice at institutions as diverse as Enron and the National Security Agency. Often at personal risk, these individuals have always brought about change and a new transparency which benefits us all.

In Britain, weapons inspector Dr David Kelly admitted in a letter to the Ministry of Defence that he had expressed misgivings about the veracity of a ‘dodgy dossier’ assembled to aid Tony Blair’s call to arms for the Iraq war. Once the news of that letter was in the public domain he was hounded by press and politicians alike. The fallout tainted the careers of all involved and drove him to take his own life. Suicide notes can be grimly fascinating, and we have included Virginia Woolf’s achingly sad last letter to her husband, as well as what was meant to be the last letter from French poet Baudelaire to his mistress. Despite stabbing himself in the chest he managed to miss any vital organs and survived to write his best work.

Better known for his rousing speeches than his letters, during World War II Churchill wrote a letter to support the Salute the Soldier campaign to raise funds for military equipment.

Other arts are represented in the book. The roots of Beatrix Potter’s popular Peter Rabbit books are in a letter she wrote to a young friend; Vincent van Gogh tried to explain his art to his brother Theo in a letter; and a letter from Mozart to his wife illustrates the frenzy of his final days of urgent composition. Pop music has largely replaced the classical repertoire in the public’s hearts. It’s incredible to think that the Beatles received a rejection letter from Britain’s leading record company at the start of their career.

Oscar Wilde is here too, but not for a letter with a string of witty bon mots. He wrote a celebrated letter from Reading Gaol, where he was forced to reflect on his wild living. Martin Luther King Jr. also found time in prison to write a long letter, in defence of the crime of civil disobedience for which he had been locked up. Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, a member of the feminist Russian punk group Pussy Riot, wrote philosophical letters during her detention for hooliganism which consider the vital role of public protest.

The neat handwriting of Queen Anne Boleyn, writing to thank Cardinal Wolsey for promoting her marriage to Henry VIII.

King and another famous prisoner, Nelson Mandela, wrote letters as part of the centuries-long fight for civil rights for Africans and African Americans. We have also included letters from Abraham Lincoln, George Washington Williams and Eleanor Roosevelt, which take stands on the subject. Addressing another aspect of social injustice, the book includes the Time’s Up letter of 2018, signed by three hundred women from the world of entertainment, which called for equality of the sexes and an end to male abuse wherever it occurs. We can only hope this brings about more change than the letter from Abigail Adams to her husband John in 1776, asking him to enshrine the rights of women in the American Constitution which he was about to help write. He thought she was joking.

There’s something about all these letters. They are a very direct link between us and those who wrote and received them, and the times when they were written. The paper and the ink and the writing are often tangible elements which bring their history alive.

I like a letter, sealed in an envelope, with a postmarked stamp, and delivered not to a virtual mailbox, but to a real one. Everyone writes emails these days and the letter seems to be on its way out. But however personal their contents, emails are never really personal, or private.

They’re not hand-written; no one has chosen the writing paper; and they can be read by anyone from your email provider to your national security agency. Emails all look the same; and they can be deleted by the accidental touch of a keyboard. They are never scented! There’s nothing to hold on to, nothing to keep, nothing to take out of your wallet or purse and re-read in a quiet moment; nothing to treasure.

Well, that’s that. I hope you like the book. If you do, why not send me a letter?

With very best wishes,

Colin Salter

The Spartans respond to a letter from Philip II of Macedon

(c. 346 BC)

A laconic phrase is the embodiment of verbal cool: a short, blunt, pithy, witty remark that deflates or dismisses a grander, more verbose person or idea. It was invented by the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta and named after their region of Greece, Laconia.

The Spartans had a fearsome reputation. Male Spartans began their military service at the age of seven with basic training. They were also educated in the arts, including the art of the reply: there were special punishments for ‘unlaconic’ answers to questions. From the ages of twenty to thirty they were pressed into national military service, and remained on call as reservists until they were sixty. If a Spartan man were called on to go to war, it was a tradition for his wife to formally present him with his shield and say, ‘With this, or on it’ – in other words, come back victorious or be carried back dead.

In nearby Macedon, King Philip II was the youngest of three brothers, whose father had unified Macedon (called Macedonia today) into a recognizable and powerful state. Warfare with neighbouring states was a family business. Although his father had lived to a ripe old age, none of his sons were so fortunate. It was only after a series of early deaths by assassination or in battle that Philip found his way to the top, when he deposed his nephew in 359 BC.

Despite his unorthodox rise, Philip proved to be an effective ruler. He reinvigorated the Macedonian army and set about restoring and expanding the country’s borders through military conquest. As Macedon’s reputation grew, sometimes the mere threat of invasion was enough to secure the surrender of a neighbouring state. In around 346 BC Philip wrote a letter to the leaders of Sparta, giving them the chance to give up without a fight. ‘You are advised to submit without further delay, for if I bring my army into your land, I will destroy your farms, slay your people, and raze your city.’ It was a cheeky offer; Sparta had been the dominant fighting force in the ancient Greek world for three hundred years. Since a defeat by Thebes in 371 BC, Sparta had been further rocked by internal slave revolts, and Philip may have sensed Spartan weakness and instability. But his letter is chiefly remembered today for the reply that he received from the Spartans.

Sparta replied simply: ‘If.’

Philip is reputed to have approached the Spartans on another occasion, writing: ‘Should I enter your lands as a friend or as a foe?’ This time the reply was just as terse: ‘Neither.’

Philip II was assassinated in 336 BC at the wedding of his daughter to a neighbouring ruler. He was succeeded by his son Alexander III, Alexander the Great. Although Alexander’s conquests extended to the subcontinent of India, the Macedonian army never did invade Sparta.

A Spartan hoplite, or citizen-soldier. The red cloak was part of the characteristic Spartan uniform, but it was discarded in battle.

The Philippeion at Olympia in Greece. This monument was erected to celebrate Philip’s complete victory at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC. His Macedonian forces routed the forces of Thebes and Athens and left him in command of all Greece … with the exception of Sparta …

Caesar’s murderers correspond to work out their next move

(March 22, 44 BC)

Scattered across various collections, there are twenty-seven letters from a remarkable correspondence between members of the conspiracy to assassinate Julius Caesar. These letters were written more than 2,000 years ago, and somehow, their contents have survived.

Julius Caesar, everyone’s favourite ancient Roman, was a brilliant military commander and a skilled politician. As a maverick general he fought unsanctioned wars, and after his move into populist politics he steered the Roman Republic towards dictatorship, with himself at the top.

Rome was ruled by a senate. While some senators showered honours and titles on Caesar, others were concerned that he was undermining the democracy of the Republic. Senator Cassius and his brother-in-law, Brutus, hatched a plot to remove the tyrannical leader. In 44 BC, on March 15 (the Ides of March, when traditionally debts had to be paid), Julius Caesar was stabbed twenty-three times on the pavement outside the Theatre of Pompey.

Assassinations don’t just plan themselves. The conspirators met in one anothers’ houses and naturally didn’t put much in writing before the event. Afterwards, however, all hell broke loose, and in a letter from Brutus to Cassius, written only a few days after the murder, he considered the conspirators’ options.

The fact that they had not been rounded up and executed already says something about the times. Caesar’s assassination was not entirely unpopular. Nor had it extended to killing his closest ally, Mark Antony: the conspirators’ only aim was the removal of a tyrant, not regime change.

However, Brutus noted that ‘it was not safe for any of us to be in Rome.’ Someone loyal to Caesar might easily seek revenge, and ‘I have determined to ask for permission, while we are at Rome, to have a bodyguard at the public expense; but I do not expect they will grant us that privilege, because we shall raise a storm of unpopularity against them.’

Meanwhile Brutus was trying to make a deal with Mark Antony that would get them out of the capital. He seems to have asked Mark Antony for a governorship, but ‘he said that he could not possibly give me my province.’ So ‘I decided to demand for myself and our other friends an honorary ambassadorship, so as to discover some decent pretext for leaving Rome.’ He is resigned to living in exile, at least for a time: ‘If there is a change for the better, we shall return to Rome; if there is no great change, we shall live on in exile.’

If Mark Antony hoped to step into Caesar’s shoes as leader, he was to be disappointed. Caesar had named his great nephew Octavian as his successor; and Caesar had already concentrated such power in his own hands that a return to the more democratic Roman Republic was impossible. Dictatorship-by-emperor was the future for the new Roman Empire.

Octavian’s first act was to declare the conspirators to be murderers. Civil war broke out between supporters of Julius and Octavian and their opponents. Brutus and Cassius fled to Greece, where they raised an army. But after they were defeated by the joint forces of Octavian and Mark Antony at the Battle of Philippi, both men committed suicide.

Letter from Decimus Brutus to Marcus Brutus and Cassius

… Being in these straits, I decided to demand for myself and our other friends an honorary ambassadorship, so as to discover some decent pretext for leaving Rome. This Hirtius has promised to obtain for me, and yet I have no confidence that he will so do, so insolent are these men, and so set on persecuting us. And even if they grant our request, it will not, I fancy, prevent us being declared public enemies or banned as outlaws in the near future.

‘What then,’ you say, ‘have you to suggest?’ Well, we must bow to fortune; I think we must get out of Italy and migrate to Rhodes, or somewhere or other; if there is a change for the better, we shall return to Rome; if there is no great change, we shall live on in exile; if it comes to the worst, we shall have recourse to the last means of defending ourselves.

It will perhaps occur to someone among you at this point to ask why we should wait for that last stage rather than make some strong effort at once? Because we have no center to rally around, except indeed Sextus Pompeius and Caecilius Bassus, who, it seems to me, are likely to be more firmly established when they have this news about Caesar. It will be time enough for us to join them when we have found out what their strength really is. On behalf of you and Cassius, I will make any engagement you wish me to make; in fact Hirtius insists upon my doing so.

I must ask you both to reply to my letter as soon as possible – because I have no doubt that Hirtius will inform me about these matters before the fourth hour – and let me know in your reply at what place we can meet, where you would like me to come.

Since my last conversation with Hirtius I have determined to ask for permission, while we are at Rome, to have a bodyguard at the public expense; but I do not expect they will grant us that privilege, because we shall raise a storm of unpopularity against them. Still I thought I should not refrain from demanding anything that I consider to be reasonable. …

Vincenzo Camuccini’s 1844 painting of the murder of Julius Caesar held by the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome.

St Paul guides the principles of Christianity through his letters

(c. 50 AD)

Letters (or epistles) attributed to Paul the Apostle make up almost half the New Testament of the Bible – thirteen of its twenty-seven books. It’s a large body of work, and it built the Christian Church on the foundations of the four Gospels.

Paul was born during Jesus’ lifetime; in fact, the two men were of similar age. But Paul, then known as Saul, was a devout Jew, a Pharisee dedicated to the persecution of Christ’s followers. On the road to Damascus to arrest some Christians, not many years after Jesus Christ’s crucifixion, Paul was confronted by a vision of Christ who asked him, ‘Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?’ Saul replied, ‘Who are you, Lord?’ and Christ said, ‘I am Jesus whom you persecute.’

Paul was temporarily blinded by the experience, which is related in the New Testament book Acts of the Apostles. When he recovered his sight three days later, he converted at once to Christianity and travelled widely, spreading the Gospel and encouraging local Christians to form groups or churches together. His letters to these churches were intended to support and strengthen their faith. Paul’s advice, and his clarifications on matters of theology, have been guiding principles of Christianity ever since.

Paul’s theology focuses on Man’s redemption through Christ’s crucifixion – the idea that Christ died for our sins. Followers of Jesus were assured forgiveness and salvation at the end of time with Christ’s Second Coming. ‘For he who has died has been freed from sin,’ he wrote in his Letter to the Romans, ‘for sin shall not have dominion over you, for you are not under law but under grace.’

In the hope of this heavenly promise, Christians had a duty to set themselves apart from the sinful ways of the world. Paul argued that a higher moral standard and faith in Jesus were more important than blindly obeying the laws of the land. ‘We walk by faith, not by sight,’ he told the Christians at Corinth. ‘Do not be conformed to this world,’ he advised the Roman church, ‘but be transformed by the renewing of your minds.’

These are aspects of Christianity that we take for granted now, but it was Paul’s letters that defined them for the earliest Christians. Whether or not you count yourself a Christian, many of the principles that Paul laid out are universal. Behind many of them are a generosity of spirit and a simple love for one’s fellow man. In another letter to the Corinthians, Paul explains it beautifully:

‘Love is patient, love is kind, and is not jealous; love does not brag and is not arrogant, does not act unbecomingly; it does not seek its own [will], is not provoked, does not take into account a wrong suffered, does not rejoice in unrighteousness, but rejoices with the truth; bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.’

First Letter of Paul to the Corinthians

Chapter 13

1 Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal.

2 And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing.

3 And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing.

4 Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up,

5 Doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil;

6 Rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth;

7 Beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things.

8 Charity never faileth: but whether there be prophecies, they shall fail; whether there be tongues, they shall cease; whether there be knowledge, it shall vanish away.

Paul’s Letter to the Romans

Chapter 13

1 Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers. For there is no power but of God: the powers that be are ordained of God.

2 Whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God: and they that resist shall receive to themselves damnation.

3 For rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil. Wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? Do that which is good, and thou shalt have praise of the same:

4 For he is the minister of God to thee for good. But if thou do that which is evil, be afraid; for he beareth not the sword in vain: for he is the minister of God, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil.

5 Wherefore ye must needs be subject, not only for wrath, but also for conscience sake.

6 For this cause pay ye tribute also: for they are God’s ministers, attending continually upon this very thing.

7 Render therefore to all their dues: tribute to whom tribute is due; custom to whom custom; fear to whom fear; honour to whom honour.

A painting of St Paul writing his epistles, attributed to the French painter Valentin de Boulogne and dated to c. 1618 to c. 1620.

The Chester Beatty Library in Dublin holds this Egyptian find, an early copy of St Paul’s Letter to the Romans.

Tablets reveal details of life at the edge of the Roman Empire

(c. 100 AD)

In the 1970s, hundreds of letters were unearthed during an archaeological dig at Vindolanda, a Roman fort in the north of England. They were written in the last decade of the first century AD, and at the time they were the oldest examples of handwriting ever found in the United Kingdom.

Vindolanda was an uncomfortable posting for any Roman soldier. ‘Vindo’ comes from the same root as the modern English word ‘winter’. One of the most northerly outposts of the Roman Empire, it could be bitterly cold, and the high average rainfall of the region was compounded by the location of the fort on wet ground. To give themselves some insulation from the elements, the Romans took to covering the packed-earth floors of their barracks with a crude carpet of straw and moss.

Dropped items were easily lost in this tangle of fibres, which was frequently topped with fresh layers. It’s thanks to this damp environment that so many items have been preserved. The letters are written in ink on thin sheets of wood about the size of a postcard. All are in Latin: some are written in a previously unknown script, which has now been deciphered, and some are in a form of shorthand that has yet to be understood. Some are letters received at Vindolanda and others are drafts of letters sent out from there to other forts in the area and further south in Roman Britain.

Around 750 letters have so far been transcribed, and they paint a vivid and previously unseen picture of daily life in this little corner of Rome. The sheer volume indicates that literacy was much more widespread than had been assumed; the letters are by members of all ranks, not just the officer class, and indeed not only by members of the army. There are messages from shoemakers and plasterers as well as wagon mechanics and men in charge of the bathhouse.

One must have accompanied a parcel: it reads in part, ‘… I have sent (?) you … pairs of socks from Sattua, two pairs of sandals and two pairs of underpants.’ Another, from the wife of an officer in a neighbouring fort to the wife of one at Vindolanda, is an invitation to a birthday party:

‘Claudia Severa to her Lepidina, greetings. On 11 September, sister, for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival, if you are present. Give my greetings to your Cerialis. My Aelius and my little son send him their greetings.’

Most of the letter has been dictated to a scribe, but Claudia Severa adds in her own hand at the end: ‘I shall expect you, sister. Farewell, sister, my dearest soul, as I hope to prosper and hail.’

It is one of the earliest pieces of Latin known to have been written by a woman.

Vindolanda was a Roman auxillary fort close to Hadrian’s Wall and occupied between 85 AD and around 370 AD. Two towers have been reconstructed at the site near the village of Bardon Mill in Northumberland.

Over 750 wooden tablets have been found at Vindolanda and more continue to be unearthed. They provide intimate details of everyday life in a Roman garrison, including the confirmation that Roman soldiers wore underpants (subligaria).

Birthday invitation from Claudia Severa to Sulpicia Lepidina

Claudia Severa to her Lepidina greetings. On 11 September, sister, for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival, if you are present. Give my greetings to your Cerialis. My Aelius and my little son send him their greetings. (2nd hand) I shall expect you, sister. Farewell, sister, my dearest soul, as I hope to prosper, and hail. (Back, 1st hand)

To Sulpicia Lepidina, wife of Cerialis, from Severa.

Memorandum on fighting characteristics of Britons

… the Britons are unprotected by armour. There are very many cavalry. The cavalry do not use swords nor do the wretched Britons mount in order to throw javelins.

Pliny the Younger describes the eruption at Pompeii to Tacitus

(c. 106/107 AD)

Pliny the Younger (61–c107 AD) was a Roman lawyer and magistrate. Pliny the Elder was his uncle and a celebrated author. Both men experienced the eruption of Vesuvius, which buried Pompeii in 79 AD, and the nephew’s letters describing the events are history’s earliest eyewitness accounts.

How many letters must Roman lawyer Pliny the Younger have written in his life, for as many as 247 of them to have survived? He was a prolific correspondent, and historians value his insights into the life of imperial Rome. His letters to and from the emperor Trajan about the legal position of early Roman Christians are fascinating documents of their time.

Pliny the Younger’s father died when he was a boy, and he was raised in Rome by his uncle, whom he greatly admired. Pliny the Elder had a post in charge of the Roman naval fleet at Misenum, west of Naples. While the nephew and his mother were visiting the uncle in 79 AD, Mount Vesuvius on the other side of the Bay of Naples, began to erupt.

When Pliny the Elder heard that people were in danger, he set sail from Misenum with a fleet of light ships to rescue them from the shore below Vesuvius. Faced with the fear and panic of those around him when he arrived, he tried to soothe them by appearing unconcerned – coolly taking a bath, a meal and a nap. This delay to his return to Misenum was fatal. Almost trapped in his bedroom by falling debris, he escaped to the shore but was overcome by noxious fumes and fell down dead.

Twenty-five years later the Roman historian Tacitus wrote to the younger Pliny to ask about his experiences of the eruption. In two replies, Pliny gave such detailed and accurate descriptions of the unfolding disaster that today volcanologists describe similar volcanic events as ‘Plinian eruptions’.

As so often with history, it is the little moments affecting ordinary people that make Pliny’s recollections leap off the page. He notes the flight of people from their houses, which are shaking from the earthquakes, to the fields where ‘the calcined stones and cinders fell in large showers, and threatened destruction. They went out,’ Pliny recalls, ‘having pillows tied upon their heads with napkins; and this was their whole defence against the storm of stones that fell round them.’

The terror of the population is palpable. ‘You might hear the shrieks of women, the screams of children and the shouts of men; some calling for their children, others for their parents, others for their husbands … some wishing to die, from the very fear of dying; some lifting their hands to the gods; but the greater part now convinced that there were no gods at all and that the final endless night of which we had heard had come upon the world.’

Of his uncle’s relaxed approach to rescue, he paints a very human picture. ‘It is most certain that he was so little disquieted as to fall into a sound sleep; for his breathing, which on account of his corpulence was rather heavy and sonorous, was heard by the attendants outside.’ Pliny the Elder is, for a moment, no longer a natural historian of repute but a fat man snoring.

Of the letters themselves, he tells Tacitus: ‘You will pick out whatever is most important; for a letter is one thing, a history quite another. It is one thing writing to a friend, another thing writing to the public.’ But in fact, such is the quality of Pliny’s writing that he has done both.

Letter from Pliny the Younger to Tacitus

… It is with extreme willingness, therefore, that I execute your commands; and should indeed have claimed the task if you had not enjoined it. He was at that time with the fleet under his command at Misenum. On the 24th of August, about one in the afternoon, my mother desired him to observe a cloud which appeared of a very unusual size and shape. He had just taken a turn in the sun and, after bathing himself in cold water, and making a light luncheon, gone back to his books: he immediately arose and went out upon a rising ground from whence he might get a better sight of this very uncommon appearance. A cloud, from which mountain was uncertain, at this distance (but it was found afterwards to come from Mount Vesuvius), was ascending, the appearance of which I cannot give you a more exact description of than by likening it to that of a pine tree, for it shot up to a great height in the form of a very tall trunk, which spread itself out at the top into a sort of branches; occasioned, I imagine, either by a sudden gust of air that impelled it, the force of which decreased as it advanced upwards, or the cloud itself being pressed back again by its own weight, expanded in the manner I have mentioned; it appeared sometimes bright and sometimes dark and spotted, according as it was either more or less impregnated with earth and cinders. This phenomenon seemed to a man of such learning and research as my uncle extraordinary and worth further looking into. He ordered a light vessel to be got ready, and gave me leave, if I liked, to accompany him. I said I had rather go on with my work; and it so happened, he had himself given me something to write out. As he was coming out of the house, he received a note from Rectina, the wife of Bassus, who was in the utmost alarm at the imminent danger which threatened her; for her villa lying at the foot of Mount Vesuvius, there was no way of escape but by sea; she earnestly entreated him therefore to come to her assistance. He accordingly changed his first intention, and what he had begun from a philosophical, he now carries out in a noble and generous spirit. He ordered the galleys to be put to sea, and went himself on board with an intention of assisting not only Rectina, but the several other towns which lay thickly strewn along that beautiful coast. Hastening then to the place from whence others fled with the utmost terror, he steered his course direct to the point of danger, and with so much calmness and presence of mind as to be able to make and dictate his observations upon the motion and all the phenomena of that dreadful scene. …

A classic engraving of the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. Pliny the Younger survived; his uncle, Pliny the Elder, perished.

Romano Britons plead for help from Rome as the empire fails

(c. 450 AD)

In the declining twilight years of the Roman Empire, Rome gradually withdrew from its outlying provinces, including Britannia – Roman Britain. The well-ordered society fostered by the Roman presence collapsed into chaos. The Dark Ages were descending …

By the time the last Roman soldiers left Britain in 407 AD, the land we now call England was under attack on all sides by Picts, Scots and Saxon marauders. Even while Roman troops still remained in Britain, the Romano Britons had felt it necessary to appeal to Rome to send reinforcements. In 368 AD the neglected garrison of Rome’s remotest outpost, Hadrian’s Wall, had revolted over conditions there and joined forces with the barbarians. Rome sent an expeditionary force, which crushed the rebellion, but in the 390s the Britons asked for further help to hold back the tide of Pictish raids from the north. ‘Owing to inroads of these tribes and the consequent dreadful prostration,’ they wrote, ‘Britannia sends an embassy to Rome, entreating in tearful appeals an armed force to avenge her.’

Rome again sent a legion, which dealt with the immediate problem. But as soon as it returned to Rome, the raids resumed, this time by Scots and Saxons from across the North Sea. The Brits wrote another letter. ‘Again supplicant messengers are sent with rent clothes and heads covered with dust. Crouching like timid fowls under the trusty wings of the parent birds, they ask help of the Romans, lest the country in its wretchedness be completely swept away.’

Rome reluctantly obliged, but it had problems of its own; elsewhere in the empire the Vandals and Visigoths were overrunning Europe, and troops were dispatched from all parts of the empire, including in 407 AD all those remaining in Britannia, to fight them off. In fury at being abandoned the Britons threw out the Roman civil administration in 409 AD, giving Emperor Honorius the excuse he needed in 410 to wash his hands of troublesome Britannia altogether.

Without any support from Europe, Britannia was now defenceless. Raiding parties from Ireland attacked Wales and the southwest; the Picts reasserted themselves in the northeast; and by the 440s there were Saxon settlements along England’s eastern shores. In around 450, Britons made another desperate appeal to Rome for help. They wrote to Flavius Aetius, the leading Roman general of his day, and in a letter headed ‘The Groans of the Britons’, they spelled out their plight. ‘The barbarians drive us to the sea, the sea drives us to the barbarians; between these two means of death, we are either killed or drowned.’ This time, there was no reply from Rome.

As a last resort a British king called Vortigern hired mercenaries from Europe – led, according to tradition, by the brothers Hengist and Horsa – who promptly turned on him in an event known as the Treachery of the Long Knives. They opened the door for a huge immigration of Angles, Saxons and Jutes from the European continent, who brought their lifestyles, culture and language to Britain. The Groans of the Britons were the dying gasps of one period of English history and the birth cries of the modern English language and modern England.

An illustration of King Vortigern meeting the mercenaries Hengist and Horsa on the Isle of Thanet, Kent. The two brothers led a wave of immigration to southeast England.

English barons try to flex their legal muscle after Magna Carta

(June 19, 1215)

The Magna Carta, the Great Charter, marked a turning point in English democracy. Under pressure from his nobles, King John relinquished the absolute power that monarchs assumed. A recently discovered letter shows just what a revolutionary moment the king’s signature at Runnymede had been.

Politics and power were ruthless games in the Middle Ages. As young men, King John’s elder brothers had rebelled against their father, Henry II, and John himself had tried to overthrow the rule of his brother Richard Lionheart, while Richard was fighting the Third Crusade in the Middle East. Despite losing that family squabble, John became king upon the death of Richard in 1199.

As king he earned the nickname ‘John Lackland’ by losing large parts of England’s Angevin territories through war in France. He offended his French barons, who deserted him, and without consultation imposed new taxes on the English barons to fund another French campaign.

The barons objected, and what began as a chaotic chorus of disaffected baronial voices became a more organised campaign of military rebellion that captured the cathedral cities of Lincoln, Exeter and London itself. King John was forced to negotiate a peace for his kingdom through the Archbishop of Canterbury.

A peace treaty, the Magna Carta, was the result. It outlined limits to the king’s abuse of traditional feudal practice; in other words, how he conducted business with the barons. It offered written guarantees of access to judicial procedure regardless of wealth, not only for the nobility but for all freemen. And it established a sort of League of Justice, a council of twenty-five barons to oversee and enforce these devolved privileges – by force if necessary. This was a new kind of government, and England’s baffled enemies could only joke that England now had twenty-six kings.

It is a document still revered by legal systems around the world for enshrining basic human rights. But at the time, in 1215, it seemed not to be taken very seriously by either party to its signing. The rebels reneged on a promise to give back London; and far from accepting a peace, John renewed his attacks on them. The civil war that ensued only ended with John’s death the following year.

A newly discovered letter, however, proves that, at least at first, some of the barons were trying to exercise their new powers. Only four days after the signing of the Magna Carta, five of the new council members wrote to the authorities in the county of Kent. It advised them that the barons were to be present at the swearing in of twelve knights, to be appointed in Kent as in each county ‘to enquire into evil customs committed by sheriffs and their ministers, in regard to forests and foresters, warrens and warreners, riverbanks and their keepers, and to ensure the suppression of such evil customs.’

This was one of the terms of the Magna Carta, and the letter was making clear that there was a new rule of law: whatever evil customs the sheriffs and their ministers, foresters, warreners and riverbank keepers had been getting away with until then, was going to stop. Here was a new broom, intent on sweeping clean. The sheriff of Kent and all the king’s bailiffs were to be in no doubt that it was to the council that their oaths should be sworn, and not to the king.

The letter was recently discovered by scholars copied into a manuscript held in Lambeth Palace Library. It is the bottom paragraph of the text. The document sheds new light on the balance of power between the King and the barons.

Letter of five of the twenty-five barons, appointing four knights to oversee the swearing of oaths and the appointment of an inquest by twelve knights in the county of Kent.