11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

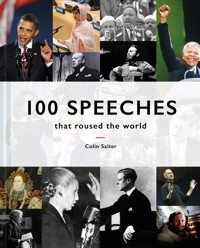

100 Speeches that Roused the World tells the stories behind the most inspiring, rousing and memorable speeches, from ancient Greece to the present day. A concise introduction and analysis of each speech is accompanied by key illustrations and photographs. 100 Speeches presents the power of the spoken word at its finest, from stirring calls to arms to impassioned pleas for peace. Speeches include: Sojourner Truth, "Ain't I a woman" (1851), Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address (1863), Emmeline Pankhurst "Freedom or Death" (1913), Winston Churchill, "Blood, Sweat and Tears" (1940), John F. Kennedy, "We choose to go to the moon" (1961), Martin Luther King, "I Have a Dream" (1963), Nelson Mandela on his release from prison (1990), Barack Obama, "Yes, We Can!" (2008) and Malala Yousafzai, "The right of education for every child" (2013). Others include Cicero, Elizabeth I, George Washington, Mahatma Gandhi, Vladimir Lenin, Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Enoch Powell, Eva Perón, Mao Zedong, Malcolm X, Margaret Thatcher, Richard M. Nixon, Maya Angelou, Steve Jobs and Oprah Winfrey. This is a classic collection of inspirational, momentous and thought-provoking speeches that have stirred nations, challenged accepted beliefs and changed the course of history.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 516

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Pictured in October, 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt prepares to make a national broadcast from the White House.

Contents

Introduction

c. 399 BC

Socrates

“I know that I know nothing”

c. 326 BC

Alexander The Great

Speech by the Hydaspes River

63 BC

Cicero

“O tempora! O mores!”

c. 31 AD

Jesus Christ

Sermon on the Mount

1305

William Wallace

“I have slain the English”

1588

Elizabeth I

“I have the heart and stomach of a king” 24

1649

Charles I

Execution speech

1775

Patrick Henry

“Give me liberty, or give me death!”

1789

William Wilberforce

Abolition of slavery speech

1794

Maximilien Robespierre

Justification for the “reign of terror”

1796

George Washington

Farewell Address

1829

Andrew Jackson

Speech to Congress on “Indian removal”

1851

Sojourner Truth

“Ain’t I a woman?”

1852

Frederick Douglass

“What to the slave is the 4th of July?”

1860

Thomas Henry Huxley

Oxford evolution debate

1861

Alexander Stephens

Cornerstone speech, justifying the confederacy

1863

Abraham Lincoln

The Gettysburg Address

1865

Abraham Lincoln

Second Inaugural Address

1877

Chief Joseph

Surrender speech

1895

Oscar Wilde

“The love that dare not speak its name”

1901

Mark Twain

Votes for Women

1913

Emmeline Pankhurst

“Freedom or Death” speech

1915

Patrick Pearse

“Ireland unfree shall never be at peace”

1917

Vladimir Lenin

“Power to the Soviets” speech

1918

Woodrow Wilson

Fourteen Points

1931

Mahatma Gandhi

“My Spiritual Message”

1933

Adolf Hitler

First speech as chancellor of Germany

1933

Franklin D. Roosevelt

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself”

1936

Edward VIII

Abdication speech

1938

Neville Chamberlain

“Peace for our time”

1939

Lou Gehrig

“The luckiest man on the face of this earth”

1939

Adolf Hitler

Obersalzberg speech

1939

George VI

Declaration of war against Germany

1939

Charles Lindbergh

Urging the US to stay neutral in WWII

1940

Winston Churchill

“Blood, toil, tears and sweat”

1940

Winston Churchill

“We shall fight on the beaches”

1940

Winston Churchill

“This was their finest hour”

1940

General de Gaulle

Appeal of June 18

1941

Vyacheslav Molotov

Radio speech on Nazi invasion

1941

Franklin D. Roosevelt

“A date which will live in infamy”

1944

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Announcing the Allies had landed in France

1946

Emperor Hirohito

Denouncing divine status

1946

Winston Churchill

“An iron curtain has descended”

1946

Albert Speer

Nuremberg Trial Testimony

1947

Jawaharlal Nehru

“Tryst with Destiny”

1948

David Ben-Gurion

Israeli Declaration of Independence

1948

Aneurin Bevan

Speech on the founding of the NHS

1949

Chairman Mao Zedong

“The Chinese people have stood up!”

1951

Eva Perón

Speech to the descamisados

1953

Queen Elizabeth II

Coronation speech

1954

Earl Warren

Racial segregation US schools ruling

1956

Nikita Khruschev

“Cult of the individual”

1960

Harold Macmillan

“The wind of change is blowing through this continent”

1960

Elvis Presley

“Home from the Army” press conference

1960

Fidel Castro

United Nations’ speech

1960

Mervyn Griffith-Jones

Lady Chatterley’s Lover Obscenity Trial

1961

John F. Kennedy

Inaugural Address

1962

John F. Kennedy

“We choose to go to the moon”

1963

John F. Kennedy

“Ich bin ein Berliner”

1963

Martin Luther King Jr.

“I have a dream”

1963

Harold Wilson

The White Heat of Technology

1964

Muhammad Ali

“I am the greatest!”

1964

Malcolm X

“The Ballot or the Bullet”

1964

Nelson Mandela

“An ideal for which I am prepared to die”

1966

John Lennon

“We’re more popular than Jesus” apology

1967

Timothy Leary

“Turn on, tune in, drop out”

1967

Earl Warren

Loving vs. Virginia

1967

Eugene McCarthy

Denouncing the Vietnam War

1968

Martin Luther King Jr.

“I’ve been to the mountaintop”

1968

Enoch Powell

Rivers of Blood

1969

Neil Armstrong

“One giant leap for mankind”

1969

Max B. Yasgur

“This is America and they are going to have their festival”

1970

Betty Friedan

Strike for Equality

1971

John Kerry

Vietnam Veterans Against the War

1973

Harry Blackmun

Roe vs. Wade

1974

Richard Nixon

Announcement of Resignation

1978

Harvey Milk

“You have to give people hope”

1980

Margaret Thatcher

“The lady’s not for turning”

1987

Ronald Reagan

“Tear down this wall!”

1990

Nelson Mandela

“We have waited too long for our freedom”

1991

Mikhail S. Gorbachev

Farewell Address

1993

Maya Angelou

“On the Pulse of Morning”

1997

Chris Patten

“A very Chinese city with British characteristics”

1997

Earl Spencer

“The most hunted person of the modern age”

1998

Bill Clinton

“I have sinned”

1998

Tony Blair

Address to Irish Parliament

2001

George W. Bush

Address to the Nation

2004

Osama bin Laden

Address to the United States

2004

Barack Obama

Keynote Address at the Democratic National Convention

2007

Steve Jobs

“Today Apple is going to reinvent the phone”

2007

Bill Gates

Commencement Address at Harvard

2008

Barack Obama

“Yes, We Can!”

2013

Malala Yousafzai

“The right of education for every child”

2016

“Emily Doe”

Stanford Rape Trial statement to court

2016

Stephen Hawking

Exploring the impact of Artificial Intelligence

2017

Ashley Judd

“I am a nasty woman”

2017

Mark Zuckerberg

Commencement Address at Harvard

2017

James Comey

Senate Testimony

2017

Elon Musk

Becoming a Multiplanet Species

2018

Oprah Winfrey

“Their time is up”

Introduction

Speeches have always been the greatest form of advocacy. The speaker’s careful choice of words, phrases, and sentences to persuade his or her audience is as creative an act as the poet’s or the playwright’s.

Speeches were at the heart of the earliest Western dramas from ancient Greece. Athenian society already had sophisticated rules for rhetoric and drama more than two and a half thousand years ago, and it’s fitting that the oldest speech in this book was given by Athenian philosopher Socrates in 399 BC.

Thanks to the ancient Greeks, speeches have become a formal part of our linguistic life. They can be simple declarations of love, defenses of high principles, or pleas in the pursuit of power—on screen, in court, or at rallies. Speeches may seem artificial but that’s precisely why they have their place in our legal and political processes. They are opportunities to think before we speak, to compose ourselves and make what we have to say really count. The 271 words which begin “Four score and seven years ago …” are among the most thoughtful ever spoken. In a few minutes its speaker Abraham Lincoln had a far greater impact at Gettysburg than Edward Everett, whose two-hour, 13,607-word oration preceded him that day.

A master of the art, Winston Churchill’s wartime speeches helped galvanize an isolated Britain.

Speeches invariably have a job to do. They must convince the listener of something; perhaps a speaker’s devotion, an apology, a government’s decision, or an accused man’s innocence. It is no surprise that some of the speeches we’ve chosen here were landmark legal rulings which advanced the rights of women and African Americans. Speeches really can change the world; but to do so, good speakers must know not only their own mind but all the rich, poetic tools of rhetoric at their disposal. They need to wield the power of language to full effect.

Speeches demand an audience, and above all speakers must be able to tailor their words to that audience—seldom will words simply spoken out loud do the job. Politicians are today schooled in the art of speech-making, but the best speakers in history have had a natural ability. Martin Luther King Jr.’s instinctive feel for rhythm and dynamics, born of the gospel music of his church, made his speeches some of the greatest ever given in the modern age. All the speech writers in the world can’t help you speak in public, but a charismatic speaker can turn an average speech or a difficult moment of history into a triumph of rhetoric. In the wrong hands such charisma is not without danger. Adolf Hitler was a mesmeric speaker, however abhorrent his ideas were.

The one hundred speeches presented here span nearly 2500 years of history. They mark pivotal moments in the story of humanity from the birth of nations to the end of empires. A handful mark significant cultural moments. The speeches were made in defeat or victory, anticipating imprisonment or liberation, sometimes urging cruelty and repression but more often arguing for social equality or scientific advancement. Kennedy’s speech declaring that “we choose to go to the moon” may have been motivated in part by the Soviet Union’s lead in the space race, but he expressed it in terms of America’s pioneering spirit and of a selfless quest for knowledge which could not fail to move his audience (and, importantly, persuade them to pay for it).

John F. Kennedy received a rapturous welcome when he spoke in Berlin.

Taken together, these one hundred speeches express some of the finest aspirations of the human heart. Of the one hundred, there are perhaps fifty which changed the world, and another fifty that mark the point at which the world changed. Malala Yousafzai’s original speech advocating education for girls in her native Pakistan was sufficiently incendiary to have the Taliban attempt her murder. The fact that they failed led to global condemnation and enabled her, once recovered, to deliver another speech at the United Nations.

Eva Perón. ‘Evita’ was a powerful advocate for her husband, Juan Perón.

More recent speeches, delivered after the invention of recording, have an automatic advantage in that we know how they sounded. Fine words are only half the battle, and the strength of many earlier speakers can only be judged by their reputation in the absence of video and audio evidence. We know how Churchill sounded when he defined the defiant British spirit in World War Two; but how did Queen Elizabeth’s famous evocation of Englishness come across to ordinary soldiers waiting to fight the Spanish Armada?

There’s a popular myth that Zhou Enlai, the Chinese premier, remarked in the 1970s—when asked to comment on the 1789 French Revolution—that it was “too soon to tell.” In fact he was commenting on the rather more recent Parisian student uprising of 1968. The final speeches in this book were given in the last ten years, and it is certainly too soon to tell what long-term impact they will have. But who could deny that, for example, Obama’s victory speech in 2008 was a profound moment in American and world history?

We close with Oprah Winfrey’s speech at the Golden Globes in 2018 which summarized the demands of women for greater respect in the workplace. Some observers believed it hinted at Ms. Winfrey’s own ambitions for public office. The “MeToo” movement described by Oprah Winfrey is righting that wrong at last, and perhaps her speech will eventually be seen to mark the greatest of all changes in the world, a move to complete equality between women and men.

Lack of space prevents us from reproducing entire speeches here. Fidel Castro’s four-and-a-half-hour lecture to the United Nations was never going to fit, while Neil Armstrong’s first words spoken on another planet was not diffcult. To convey as much as possible of the longer speeches we have included edited highlights. We hope the original speakers will forgive us and not feel that we have distorted their meaning. The full texts of almost all the one hundred speeches are widely available online.

In the electronic age it sometimes seems as if speeches have had their day. Speeches have given way to the soundbite, which has been elbowed sideways by the 140 characters of a tweet. So it was reassuring, that at Senator John McCain’s memorial service in 2018, Barack Obama was asked to speak, and once again we heard a politician weighing his words carefully and sounding presidential.

Martin Luther King Jr. delivering his “I have a dream” speech in 1967, from in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

Anyone with a vision of a better future still wants to talk about it, whether it’s Stephen Hawking talking about Artificial Intelligence or Elon Musk reviving the spirit of Kennedy in his push to Mars. Those seeking change are moved to the finest words, and we should listen.

Colin Salter 2018

Oprah Winfrey announces “Their time is up” at the 2018 Golden Globes.

Socrates

“I know that I know nothing”

(c. 399 BC)

Socrates saw himself as an irritant sent by the gods to sting the Athenians into action with his satire and criticism. He was charged with corrupting the youth of the city and with disregarding the city’s gods. Plato, a student of Socrates, was present at his mentor’s trial and later wrote down Socrates’s defense of his actions.

None of Socrates’s own writings survive, and we rely on Plato for a sense of the man and his philosophy. Although Plato wrote his record of the trial in the form of dramatized conversations between Socrates and his accusers, his presence at the proceedings must make it a reasonably accurate version of the arguments, if not the words themselves.

Plato’s style of writing is known as Socratic, and it is probably how Socrates himself rehearsed his arguments – by encouraging his audience or his characters to ask questions and then answering them philosophically. Although he denied it, Socrates was a follower of sophism, in which wise men were paid to impart their wisdom to rich men’s sons using the powers of philosophy and rhetoric. In such relationships, there was a clear opportunity (or danger) of subverting the young with unconventional ideas. Socrates took very public pride in his nonconformity.

At his trial, however, he denied wisdom and protested his ignorance. He had once been told at the Oracle of Delphi that there was no one wiser than him; he claimed that he only believed the assertion because oracles never lie. He searched among the learned, among poets and even among politicians for wise men; but although he found knowledge and even genius in a few, Socrates found no one who used these things wisely.

“Yet,” he countered, “each man is thought wise by the people, and each man thinks himself wise; therefore, I am the better man, because I know that I know nothing.” This, he argued, was the real reason behind the accusations against him. “For those who I have examined, instead of being angry with themselves [for not being wiser], are angry with me!”

Socrates claimed that he could not have corrupted youth because he was not a sophist; and he was not a sophist because he chose a life of unpaid poverty. He was not paid to teach; young wealthy Athenians simply followed him around and asked him questions, having nothing better to do. None had come forward as witnesses for the prosecution.

In the charge of ignoring Athenian gods in favour of his own, he argued that his gods forbade him from acting unethically, thereby admitting that he followed his own spiritual path and not that of Athens. But he insisted that he was respectful of authority, even though he admitted, “all day long I never cease to settle here, there, and everywhere, rousing, persuading, reproving every one of you.”

Socrates demonstrated that respect for his accusers when the verdict was returned by a jury of 500 of his peers: guilty. He was sentenced to death, but by tradition he was allowed to propose an alternative punishment. By convention a condemned man might escape death at this stage by suggesting he be exiled from the city or by the payment of a large fine. Socrates accepted, as his philosophical position dictated, that the city fathers were right to condemn him. Instead of a fine, he suggested that he should be kept in financial security by the city for the rest of his life, since his existence provided such a useful service of questioning its values. When this proved unacceptable to the judges, he offered to pay a desultory sum, a hundred drachmae, as a fine. His supporters quickly tried to avoid offence by raising the amount to three thousand; but the judges had had enough of his wisdom.

The death sentence was upheld. Socrates refused to flee the city as was expected of men in his position. To do so, he said, was to show a fear of death and a disrespect of the rule of law unbecoming of a philosopher. Instead, he drank the offered cup of poison.

Wherefore, O judges, be of good cheer about death, and know this of a truth, that no evil can happen to a good man, either in life or after death. He and his are not neglected by the gods; nor has my own approaching end happened by mere chance. But I see clearly that to die and be released was better for me; and therefore the oracle gave no sign. For which reason also, I am not angry with my accusers, or my condemners; they have done me no harm, although neither of them meant to do me any good; and for this I may gently blame them.

Still I have a favour to ask of them. When my sons are grown up, I would ask you, O my friends, to punish them; and I would have you trouble them, as I have troubled you, if they seem to care about riches, or anything, more than about virtue; or if they pretend to be something when they are really nothing, then reprove them, as I have reproved you, for not caring about that for which they ought to care, and thinking that they are something when they are really nothing. And if you do this, I and my sons will have received justice at your hands.

The hour of departure has arrived, and we go our ways – I to die, and you to live. Which is better God only knows.

SPEECH GIVEN AT TRIAL, AS RECORDED IN PLATO’SAPOLOGY OF SOCRATES

A first-century sculpture of Socrates held by the Louvre Museum in Paris – believed to be a copy of a lost bronze statue by Lysippos. His last words were, to a wealthy friend, “I owe Asclepius a rooster. Please pay my debt.” Thus he sought to fulfill his commercial obligations as, by dying, he was fulfiling his social contract with the state.

Alexander the Great

“The utmost hopes of riches or power ... will be far surpassed”

(c. 326 BC)

In a long and successful campaign, Alexander the Great of Macedonia conquered all of Greece, Egypt and Persia. Now he stood at the border of a vast prize – India. But his armies, weary from ten years of constant battle, wanted to go home. Alexander had to convince them that it was worth going on.

“I observe, gentlemen, that when I would lead you on a new venture you no longer follow me with your old spirit.” We rely largely on a historian called Arrian for the text of this speech, and for our knowledge of Alexander’s conquests. Although written down in the second century AD, five hundred years after the events that it describes, Arrian’s account of the military life of Alexander the Great is based on earlier histories, now lost. These were written by two men, Ptolemy and Aristobulus, who both served with Alexander. Arrian’s version, therefore, has some authority.

Alexander, King of Macedonia, knew that his troops were jaded. So very far from home, they must already have looted wealth beyond their wildest dreams as they swarmed over most of the known world to the east. No wonder the enthusiasm had begun to drain from their battle cries. They were ten years older, and so were their wives and children. Was another notch on the imperial bedpost worth it?

Their leader mustered many arguments to convince them it was. Firstly, it would be easy. “These natives either surrender without a blow or are caught on the run – or leave their country undefended for your taking.” Secondly, they had come so far, and there was so little left to conquer, “a small addition to the great sum of your conquests. The area of the country still ahead of us from here to the Ganges is comparatively small.” This was not strictly true. Alexander and his troops were on the banks of the Hydaspes River (now the Jhelum River) in northwestern India, some 1,500 miles from the Ganges delta. Furthermore, Alexander’s claim that they would be able to sail home afterwards because the Indian Ocean was connected to the Caspian Sea did not hold water.

A Greek silver tetradrachm coin of Alexander the Great, from around 323 BC.

Alexander reasoned that a soldier’s job was to fight, and that a man’s work “has no object beyond itself.” But he also made a military case for pressing on. To leave the job of conquering the world half done would be to leave the door open to insurgents from territories not yet subdued. It was worth a little extra push, surely? “For well you know that hardship and danger are the price of glory, and that sweet is the savour of a life of courage and of a deathless renown beyond the grave.” This was a direct appeal to his men’s machismo; after all, if they wanted to avoid danger, they could all just have stayed at home defending Macedonia’s borders.

As Alexander reeled off the list of conquered kingdoms, there was no denying the scale of their success so far. He was at pains from the start of the speech to credit his men for it. It had been won “through your courage and endurance.” He returned to the theme at the end: “You and I, gentlemen, have shared the labour and shared the danger, and the rewards are for us all.”

Finally, Alexander appealed to any fighting soldier’s greatest self-interest: loot. “The conquered territory belongs to you; from your ranks the governors of it are chosen; already the greater part of its treasure passes into your hands, and when all Asia is overrun, then indeed I will go further than the mere satisfaction of your ambitions: the utmost hopes of riches or power which each one of you cherishes will be far surpassed.”

That individualization – “each one of you” – was a masterstroke. And it worked. The army stayed and won a tactically brilliant battle to take control of the Punjab. But it sustained relatively heavy losses. When Alexander began to size up Bengal, the next kingdom to conquer, his generals decided that enough was enough. Alexander, unbeaten in battle, conceded defeat and advanced no further than the banks of the Indus River. King of a vast empire, he died in Babylon three years later, at the age of just thirty-two.

For a man who is a man, work, in my belief, if it is directed to noble ends, has no object beyond itself; none the less, if any of you wish to know what limit may be set to this particular campaign, let me tell you that the area of country still ahead of us, from here to the Ganges and the Eastern Ocean, is comparatively small. You will undoubtedly find that this ocean is connected with the Hyrcanian Sea, for the great Stream of Ocean encircles the earth.

Moreover I shall prove to you, my friends, that the Indian and Persian Gulfs and the Hyrcanian Sea are all three connected and continuous. Our ships will sail round from the Persian Gulf to Libya as far as the Pillars of Hercules, whence all Libya to the eastward will soon be ours, and all Asia too, and to this empire there will be no boundaries but what God Himself has made for the whole world.

But if you turn back now, there will remain unconquered many warlike peoples between the Hyphasis and the Eastern Ocean, and many more to the northward and the Hyrcanian Sea, with the Scythians, too, not far away; so that if we withdraw now there is a danger that the territory which we do not yet securely hold may be stirred to revolt by some nation or other we have not yet forced into submission.

Should that happen, all that we have done and suffered will have proved fruitless – or we shall be faced with the task of doing it over again from the beginning. Gentlemen of Macedon, and you, my friends and allies, this must not be. Stand firm; for well you know that hardship and danger are the price of glory, and that sweet is the savour of a life of courage and of deathless renown beyond the grave.

SPEECH BY THE HYDASPES RIVER

Charles Le Brun’s portrait of Alexander with Hephaestion (in the red cloak) a friend and key general.

Cicero

“O tempora! O mores!”

(63 BC)

Marcus Tullius Cicero was a Roman politician who reached the pinnacle of the political system when he was elected consul for the year 63 BC. When in the course of the year he was handed evidence incriminating a rival in a plot to overthrow the government, he saw an opportunity to make his mark on the political stage.

When, O Catiline, do you mean to cease abusing our patience? How long is that madness of yours still to mock us? When is there to be an end of that unbridled audacity of yours, swaggering about as it does now? Do not the nightly guards placed on the Palatine Hill – do not the watches posted throughout the city – does not the alarm of the people, and the union of all good men – does not the precaution taken of assembling the senate in this most defensible place – do not the looks and countenances of this venerable body here present, have any effect upon you?

Do you not feel that your plans are detected? Do you not see that your conspiracy is already arrested and rendered powerless by the knowledge which every one here possesses of it? What is there that you did last night, what the night before – where is it that you were – who was there that you summoned to meet you – what design was there which was adopted by you, with which you think that any one of us is unacquainted?

Shame on the age and on its principles! The senate is aware of these things; the consul sees them; and yet this man lives. Lives! Aye, he comes even into the senate. He takes a part in the public deliberations; he is watching and marking down and checking off for slaughter every individual among us. And we, gallant men that we are, think that we are doing our duty to the Republic if we simply keep out of the way of his frenzied attacks.

CATILINE ORATIONS; ACCUSING CATILINE OF LEADING A PLOT TO OVERTHROW THE ROMAN GOVERNMENT

C icero is regarded as one of the finest orators of the Roman Age. Reverence for classical Greece and Rome made him a role model for future writers and speakers throughout Europe well into the eighteenth century. The four speeches known as the Catiline Orations, which he made in accusing the leader of the 63 BC conspiracy, are considered among his best.

Lucius Sergius Catilina – Catiline – stood against Cicero in the consular elections for 63 BC, and lost. His campaign platform – debt relief for ordinary Roman citizens – displeased the elite in whose hands the election lay. It was a bitter blow for a man with a long family history of public service to live up to. Catiline wanted revenge and built a secret coalition of soldiers and senators with their own axes to grind, who between them mustered an army of some 10,000 men.

When Cicero learned of the rebellion, he called a special meeting of the senate and ambushed Catiline with a short but hard-hitting speech. His introductory remarks consisted entirely of rhetorical questions – fifteen of them in less than two hundred words. “What is there that you did last night, what the night before, where is it that you were, who was there that you summoned to meet you, what design was there which was adopted by you, with which you think that any one of us is unacquainted?”

These were questions that required no answer, accusations disguised as questions, which rained down on Catiline like hailstones. Cicero continued with a declaration that has become a byword for corruption in society: “O tempora! O mores!” Literally “Oh, the times! Oh, the values!” loosely translated as “What have we come to in this day and age?” Catiline tried to discredit his accuser by comparing Cicero’s humble origins with his own noble ones, before yelling threats as he stormed out of the chamber.

In the coming days, Cicero spoke twice in public about the plot. Aware that Catiline’s election platform might have made him popular with the masses, he told them that Catiline had gone not into self-imposed exile as he claimed, but to join his rebel forces. When several of Catiline’s co-conspirators were captured and made to confess, Cicero spoke in reassuring terms, declaring the public to be safe because he (with no false modesty) had prevented an uprising that had threatened great loss of life. “You see this day, O Romans, all your lives, your wives and children, this most fortunate and beautiful city, by the great love of the immortal gods for you, by my labours and counsels and dangers, snatched from fire and sword, and almost from the very jaws of fate, and preserved and restored to you.”

Finally, in the fourth oration, Cicero addressed the senate again. Consuls were supposed to be impartial in matters of law, but Cicero chose his words with such skill as to enable other speakers to call for the death sentence for all the conspirators. And he was very careful, in the most self-effacing manner, to take as much credit for the successful removal of the threat. “I ask nothing of you but the recollection of this time and of my whole consulship. I recommend to you my little son, to whom it will be protection enough if you recollect that he is the son of him who has saved all these things at his own single risk.”

The conspirators were duly executed by strangulation. Catiline was killed in battle while on the run with the rump of his army. Cicero continued to be a political operator in Rome until he misjudged his last opponent, Mark Antony. In revenge for his searing verbal and written attacks, his head and hands were cut off and nailed up in the Roman Forum, where Antony’s wife is reported to have pulled out Cicero’s persuasive tongue and stabbed it repeatedly with a hairpin.

A bust of Marcus Tullius Cicero held by the Museo Capitolino in Rome.

Jesus Christ

Sermon on the Mount

(c. 31 AD)

Of all the passages of the New Testament of the Bible, chapters five, six and seven of Matthew’s Gospel are among the richest. They contain a detailed account of Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, a speech to his followers that laid out the principles of Christianity.

Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth. Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.

Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God. Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God. Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake.

Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you. Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt have lost his savour, wherewith shall it be salted? It is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out, and to be trodden under foot of men.

Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hid. Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house. Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven.

SERMON ON THE MOUNT

J esus began his ministry at the age of about thirty when he was baptized by John the Baptist. He preached in Galilee and performed miracles, and by the age of thirty-one he had built up a large following. Perhaps in search of a natural amphitheatre to amplify his voice he walked up into the mountains of the region and began to address the multitude.

The Sermon on the Mount is the longest continuous speech by Jesus in the Bible. Phrases and sayings from it have entered the English language and are so widely used that you may not even realize where they come from. “Salt of the earth” and “light of the world” are just two of the metaphors employed, both of them to describe Jesus’s followers and their effect on daily life, improving and illuminating its condition.

“Turn the other cheek”, “go the extra mile”, “no man can serve two masters”, “ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find.” It may seem dismissive or disrespectful to assess the founder of a religion purely in terms of oratory, but the words attributed to Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount show a genius for the simple metaphor, the catchy slogan that encapsulates an entire moral idea.

The Sermon on the Mount reveals a fine orator, capable of holding and persuading an audience. Nowhere are the speaker’s rhetorical instincts better revealed than in the opening section on the theme of happiness, known today as the Beatitudes. The title comes from the Latin word ‘beatus’, which is usually translated as ‘blessed’ but also means ‘happy’. “Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.” In all, the word is used nine times to describe different ways to be morally and spiritually happy, in a rhythmic call and response.

As if all these rhetorical treasures were not enough, the Sermon on the Mount is also used to unveil an example of a good prayer to offer up to God – so good that it has become the central prayer of Christianity, the Lord’s Prayer.

The sermon closes with more vivid imagery for its audience, a simple choice that must surely have been illustrated by the mountains at hand: “Whosoever heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them, I will liken him unto a wise man, which built his house upon a rock: and the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell not: for it was founded upon a rock. And every one that heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them not, shall be likened unto a foolish man, which built his house upon the sand: and the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell: and great was the fall of it.”

The Sermon on the Mount remains the single most defining text of Christianity, and many of its moral commandments are common to other religions too. Leo Tolstoy and Mahatma Gandhi corresponded on its message of nonviolence, for example. Although theologians continue to debate its finer points, it is a masterpiece of the spoken word, packed full of big ideas yet presented with poetic simplicity for the masses.

The most likely site for the Sermon on the Mount is a hill near Tabgha in Israel, overlooking the sea of Galilee. A Roman Cathlic church, the Church of the Beatitudes, was built there in 1938.

William Wallace

“I have slain the English”

(August 23, 1305)

Not all cinematic histories are accurate. Braveheart, the biopic of Scottish ruler William Wallace, is wider of the mark than most. Its very title was not applied to Wallace but to his successor, Robert the Bruce. However, its depiction of Wallace’s mock trial and torturous execution are uncomfortably close to the truth.

A fter the death of King Alexander III of Scotland there was a political vacuum in the country, which Edward I of England was quick to fill. He installed a weak king, John Balliol (now known in Scotland as Toom Tabard, ‘the empty coat’), then deposed him and invaded Scotland.

Wallace was one of a number of leaders of small, local rebellions throughout the country that eventually joined forces and began to inflict significant defeats on the English both in Scotland and in northern England. He took the title of Guardian of Scotland, since John Balliol was still alive but in exile in France.

But Edward sent another army, which crushed Wallace’s forces at Falkirk, and from then on Wallace was a fugitive. He resigned as Guardian but conducted diplomatic missions overseas in search of support for Scotland. In 1305, he was betrayed by a Scottish knight who supported King Edward, and taken to London to be tried.

The trial was a mockery, and William Wallace was not allowed to speak in his own defence. But when one of the charges was read out – of treason against the English king – he could bite his tongue no longer:

“I can not be a traitor, for I owe him no allegiance. He is not my Sovereign; he never received my homage; and whilst life is in this persecuted body, he never shall receive it. To the other points whereof I am accused, I freely confess them all. As Governor of my country I have been an enemy to its enemies; I have slain the English; I have mortally opposed the English King; I have stormed and taken the towns and castles which he unjustly claimed as his own. If I or my soldiers have plundered or done injury to the houses or ministers of religion, I repent me of my sin; but it is not of Edward of England I shall ask pardon.”

The decision of the judge was a foregone conclusion, and he was sentenced to the traitor’s death; to be hung, drawn and quartered. In a gratuitous process of barbaric cruelty the prisoner was strangled with a rope but not killed. Then, still alive, he was made to watch as he was mutilated and his severed organs burned in fire. Finally, he was beheaded and his body cut into four pieces, in Wallace’s case, to be displayed at four northern towns.

One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter. Edward of England may have disposed of a troublesome revolutionary; but the Scots, taunted by the show of Wallace’s arms and legs in Newcastle, Berwick, Stirling and Perth, became more determined than ever to regain their independence. Led by Robert the Bruce, now King Robert, they did so decisively in 1314 at the Battle of Bannockburn.

Scotland’s fortunes waxed and waned in the following centuries, and in 1707, after the disastrous Darien Scheme almost bankrupted the country, decided their future prosperity was better served by joining England in the United Kingdom. The memory of Wallace, Bruce and Bannockburn has been romanticized since then, not only by Hollywood but authors of historic fiction such as Sir Walter Scott and Nigel Tranter. Robert Burns wrote the ballad ‘Scots Wha Hae’ in 1796; and the Wallace Monument, a Gothic tower near Stirling, was erected in 1869. William Wallace was no saint, but his memory is still invoked by Scottish nationalists today.

Ican not be a traitor, for I owe him no allegiance. He is not my Sovereign; he never received my homage; and whilst life is in this persecuted body, he never shall receive it. To the other points whereof I am accused, I freely confess them all. As Governor of my country I have been an enemy to its enemies; I have slain the English; I have mortally opposed the English King; I have stormed and taken the towns and castles which he unjustly claimed as his own. If I or my soldiers have plundered or done injury to the houses or ministers of religion, I repent me of my sin; but it is not of Edward of England I shall ask pardon.

TRIAL STATEMENT

A painting of William Wallace held by the Stirling Smith Art Gallery, Stirling, Scotland.

Elizabeth I

“I have the heart and stomach of a king”

(August 9, 1588)

England was under threat, and ill-prepared to defend itself. There was not enough money in the coffers to maintain a large standing army; the one that Elizabeth I addressed at Tilbury had been hastily assembled to face an attack by the approaching Spanish Armada. The queen’s speech is one of the earliest on record to appeal to the Englishman’s sense of his country, his sovereign, and his God.

Let tyrants fear. I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and goodwill of my subjects; and therefore I am come amongst you, as you see, at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live and die amongst you all; to lay down for my God, and for my kingdom, and my people, my honour and my blood, even in the dust.

I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm: to which rather than any dishonor shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.

I know already, for your forwardness you have deserved rewards and crowns; and We do assure you in the word of a prince, they shall be duly paid you. In the mean time, my lieutenant general shall be in my stead, than whom never prince commanded a more noble or worthy subject; not doubting but by your obedience to my general, by your concord in the camp, and your valor in the field, we shall shortly have a famous victory over those enemies of my God, of my kingdom, and of my people.

SPEECH TO THE TROOPS AT TILBURY IN PREPARATION FOR THE ANTICIPATED INVASION BY THE SPANISH ARMADA

Elizabeth’s predecessor on the English throne was her Catholic half-sister Mary I, who was married to the Spanish king Phillip II. With Mary’s death Phillip lost his influence over the English throne and sought to regain it by deposing the Protestant Queen Elizabeth. The Spanish Armada was a fleet of 130 ships whose mission was to carry troops from Flanders (modern-day northern Belgium) to invade England in support of the claim to the English throne of another Mary, Queen of Scots, a devout Catholic.

Elizabeth responded by supporting Protestant rebellion in the Spanish-held territories in northern Europe centred on Brussels, and in 1587, she ordered the execution of the Scottish queen after the discovery in 1856 of an assassination plot. The Armada set sail from northern Spain in May 1588, and on July 19 was sighted off Cornwall. A series of skirmishes with the English navy forced the Armada into a weak defensive position off Calais. The Spanish fleet was dispersed in a final English assault on July 29 and fled to the North Sea.

Deprived of their transport for the time being, the Spanish troops in Flanders nevertheless remained a threat. Elizabeth’s job in speaking to the ragged assembly of English recruits was to fire them up with a sense of nationality and superiority. In her speech, she placed herself firmly both at the head of her troops and by their side in battle; in a speech of just over 300 words, she used the word ‘my’ fifteen times, five of them in variations of the protective notion of ‘my people’.

When she said that, “We shall shortly have a famous victory”, it was not the royal ‘We’ but an implied alliance between the people and the Crown. At the beginning and at the end of the speech she drew together her religion, her country and its citizens in the phrase, “my God, my kingdom, and my people.”

She had by then been on the English throne for twenty-nine years, and displayed in her Tilbury speech a surprisingly good understanding of the common people of her kingdom. Having appealed to their patriotism, she gets down to the nitty-gritty: “I know already, you have deserved rewards and crowns; and we do assure you, they shall be duly paid you.” Plunder and the queen’s shilling were great motivators for the soldiers in a volunteer army.

It’s a remarkably personal speech from a monarch who, in the Tudor period, would have had very little direct contact with the ordinary population. Its most intimate moment is the point, at the very heart of the speech, when she confronted the question of her sex. She was a woman, not a warrior, after all; a queen (and a virgin queen at that), not a battle-hardened general. She met her critics head on: “I know I have the body of but a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.” She emphasized the point by wearing a helmet and a breast plate of armour. Combined with a white velvet cloak and mounted on a white horse, her appearance must have been dazzling to the unwashed masses who heard her.

The survival of many contemporary accounts of the queen’s performance at Tilbury confirms its effect. Its patriotic rallying cry made an immediate impact, one which only grew in the weeks and years that followed. Although the threatened invasion of England never came, Elizabeth’s impassioned appeal has become a defining moment of Englishness to rival any drafted by Shakespeare or Churchill.

The portrait of Elizabeth I, circa 1588, held by the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Charles I

“I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown”

(January 30, 1649)

Charles I was the latest in a virtually unbroken line of monarchs who ruled Britain by divine right. He occupied the throne, he believed, by the authority of God, not of man. His high-handed approach to the government of his country led to civil war and, ultimately, his own execution. As he awaited the executioner’s axe he addressed the expectant crowd with remarkable royal dignity.

B elieving in his absolute authority to rule the country as he saw fit, Charles I had found many ways to anger his subjects. He imposed taxes directly, without consulting Parliament. As king he was also Head of the Church of England, a Protestant denomination. But he tried to impose a very high Anglican version of Christianity on England, and he married a Catholic French princess. Many of his more puritanical Presbyterian subjects were offended.

In Scotland, where he tried to install bishops in a country generally opposed to such a church hierarchy, war broke out. Armed opposition to his style of rule then spread to the whole of Britain, which became bitterly divided by civil war from 1642 onwards. When he was at last captured, Charles was tried for treason, an offence that carried the death penalty. He was found guilty, and the death warrant was signed by Oliver Cromwell, leader of the Parliamentarian forces.

Charles accepted the ruling as an act of God, although he protested his innocence. He wore two shirts on the cold January morning of the execution, lest his shivering be mistaken for fear. He had refused to defend himself at his trial on the grounds that he did not recognize the court. Now, however, as the moment of his death approached, he spoke thoughtfully about his religion and his hopes for his country and its people. “My charity commands me to endeavour to the last gasp the peace of the kingdom.”

He was critical of the use of force to govern and insisted that it was the Parliamentarians who started the armed conflict. He suggested a national synod to debate the form that national religion should take. As for the people, he called for “laws by which their life and their goods may be most their own.” But he drew the line at democracy. “It is not for having share in government, Sir; that is nothing pertaining to them.”

Charles broke off twice during his speech to warn other people on the scaffold about the axe. He wasn’t concerned so much for their safety as for the sharpness of the blade – any chip or blow to it would dull the edge and make for a messier execution. In a final exchange with his executioner, he told him, “I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown where no disturbance can be.”

The decision to kill a king was a shocking one and his enemies had to go back to the Roman Empire to find a law that might justify it. Many, even in Cromwell’s camp, were opposed to carrying it out; and when the deed was done, the crowd of 10,000 did not roar in a bloodthirsty manner but gasped as one, “a moan as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again” according to one onlooker.

Following Charles’s death, the monarchy was formally abolished and Britain became for a few years a republic, and then a protectorate under the supreme leadership of Oliver Cromwell. Cromwell closed down first the House of Lords and then the House of Commons. The irony was plain for people to see – one absolute ruler had been replaced by another – and within a year of Cromwell’s death the monarchy was restored in the person of Charles’s son, Charles II.

For the King, indeed I will not argue. The Laws of the Land will clearly instruct you for that; therefore, because it concerns My Own particular, I only give you a touch of it.

For the people, and truly, I desire their Liberty and Freedom as much as any Body whomsoever. But I must tell you that their Liberty and Freedom consists in having of Government; those Laws, by which their Life and their goods may be most their own. It is not for having share in government, Sir; that is nothing pertaining to them. A subject and a sovereign are clean different things, and therefore until they do that, I mean, that you do put the people in that liberty as I say, certainly they will never enjoy themselves.

Sirs, It was for this that now I am come here. If I would have given way to an Arbitrary way, for to have all Laws changed according to the power of the Sword, I needed not to have come here; and therefore, I tell you, and I pray God it be not laid to your charge, that I am the Martyr of the People.

In troth, Sirs, I shall not hold you much longer, for I will only say thus to you. That in truth I could have desired some little time longer, because I would have put then that I have said in a little more order, and a little better digested than I have done. And, therefore, I hope that you will excuse Me.

I have delivered my Conscience. I pray God, that you do take those courses that are best for the good of the Kingdom and your own Salvations.

EXECUTION SPEECH

The triple portrait of Charles I, painted by Sir Anthony van Dyck around 1635, part of the Royal Collection.

Patrick Henry

“Give me liberty, or give me death!”

(March 23, 1775)

At the second of a series of conventions in Virginia that campaigned for American independence from Britain, Patrick Henry called for the state’s militia to be used against occupying British troops. His powerful words carried the day and set in motion the events that culminated in the American Revolution.

P atrick Henry already had a reputation as a fiery speaker. In 1760, as a young attorney he successfully upheld a new law enacted in Virginia, which had been overruled by the British king. His sense of the injustice of London rule may have stemmed from that moment. In 1765, he was a vocal opponent of the Stamp Act, by which the paper used in the American colonies for everything from newspapers to playing cards had to come from Britain and bear a British stamp to prove it.

In 1775, he was a delegate at the Second Virginia Convention, a gathering of those actively seeking an end to the state’s colonial status. Tensions were high in the thirteen colonies ruled from London; there were British soldiers everywhere, so the Convention met in Richmond, not Williamsburg, which was the state capital at the time. A petition calling for reconciliation had earlier been handed to the British governor and some delegates believed it would be sensible to wait for his response before deciding on any further action.

For Patrick Henry, however, enough was enough. “It is natural to man,” he began, “to indulge in illusions of hope.” But what, he asked his more cautious colleagues, were they hoping for? His argument against hope took the simple rhetorical form of a series of questions and answers, mostly addressing the presence of British troops in such historically high numbers. “Are fleets and armies necessary to a work of love and reconciliation? Have we shown ourselves so unwilling to be reconciled, that force must be called in to win back our love? Let us not deceive ourselves. These are the implements of war and subjugation – the last arguments to which kings resort.”

It was clear, he reasoned, that all peaceful attempts at reconciliation over the past ten years had failed. “There is no longer any room for hope.” He paused, before confronting his audience with a crescendo of their shared dreams. “If we wish to be free – if we mean to preserve inviolate those inestimable privileges for which we have been so long contending – if we mean not basely to abandon the noble struggle in which we have been so long engaged, and which we have pledged ourselves never to abandon until the glorious object of our contest shall be obtained…” and if they really wanted all this, he declared, “We must fight! I repeat it, sir, we must fight!”

There were more questions. “They tell us, sir, that we are weak, unable to cope with so formidable an adversary. But when shall we be stronger? Will it be the next week, or the next year? Will it be when we are totally disarmed, and when a British guard shall be stationed in every house? … Shall we acquire the means of effectual resistance, by lying supinely on our backs, and hugging the delusive phantom of hope, until our enemies shall have bound us hand and foot?” The alternative to battle was slavery, he suggested. It was a persuasive image, given that most of his audience were Virginia plantation owners who possessed many slaves. “Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!”

Patrick Henry won the day, and the Virginia militia was committed to a revolutionary war, which led the following year to a declaration of independence. Henry would serve two terms as governor of post-colonial Virginia. Also in the room that night in Richmond were two future presidents of the United States: George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, both Virginian tobacco growers whom Patrick Henry’s vision must have guided through the years.

They tell us, sir, that we are weak. Sir, we are not weak if we make a proper use of those means which the God of nature hath placed in our power. Three millions of people, armed in the holy cause of liberty, and in such a country as that which we possess, are invincible by any force which our enemy can send against us.

Besides, sir, we shall not fight our battles alone. There is a just God who presides over the destinies of nations; and who will raise up friends to fight our battles for us. The battle, sir, is not to the strong alone; it is to the vigilant, the active, the brave.

Besides, sir, we have no election. If we were base enough to desire it, it is now too late to retire from the contest. There is no retreat but in submission and slavery! Our chains are forged! Their clanking may be heard on the plains of Boston! The war is inevitable and let it come! I repeat it, sir, let it come.

It is in vain, sir, to extenuate the matter. Gentlemen may cry, ‘Peace, Peace,’ but there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

“GIVE ME LIBERTY, OR GIVE ME DEATH!” SPEECH

A Currier & Ives hand-coloured lithograph of the speech, published in 1876 to commemorate the centenary of the Revolution.

William Wilberforce

“A trade founded in iniquity, and carried on as this was, must be abolished”

(May 12, 1789)

A great many people got rich on the back of the slave trade, whether in the buying and selling of human beings, the use of them as cheap labour, or the sale of goods produced from their crops. Wealthy British politicians turned a blind eye to the barbarity of slavery, until William Wilberforce forced them to look.

W illiam Wilberforce was a reluctant parliamentary poster boy for the antislavery movement. He accepted the role because speaking out against the trade was a moral imperative. Slavery had been illegal on English soil following a 1772 court case, but slavery in the colonies and the business of slave trading was not. Others in Wilberforce’s circle were far better informed, and he relied on their research as he threw himself into the task, “provided that no person more proper could be found.” Eventually, it was his friend Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger who persuaded him to address Parliament on the matter. “Do not lose time,” Pitt argued, “or you will lose the ground to another.”

He was nervous when he rose for the first time to address the issue in the House of Commons. He had been an MP for seven years by then, but was daunted not only by his new mission, but by the weight of opposition that he knew he faced from the House. He was at pains to be dispassionate, simply to present the facts, not to blame. “I mean not to accuse any one, but to take the shame upon myself, in common, indeed, with the whole parliament of Great Britain, for having suffered this horrid trade to be carried on under their authority. We are all guilty.”

He excused the merchants of Liverpool, who greatly profited from the trade, by allowing that the business of slavery was such a large one that they may have lost sight of slaves as individuals. He described conditions aboard the slave ships: “If the wretchedness of any one of the many hundred negroes stowed in each ship could be brought before their view, and remain within the sight of the African merchant, that there is no one among them whose heart would bear it.” But he was not so generous with a certain Mr Norris of Liverpool, an apologist for the slave trade for whom “interest [has drawn] a film across the eyes so thick that total blindness could do no more.”