24,71 €

Mehr erfahren.

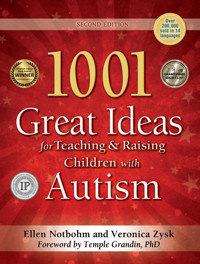

"Anyone browsing autism books might question that two authors could amass this many ideas and that all of them would be ‘great,’ but this book delivers.” — from the Foreword by Dr. Temple Grandin

Over 1800 try-it-now tips, eye-opening perspectives, and time-saving strategies abound in this revised edition of the 2004 multi-award-winning book that has been read and reread again and again by hundreds of thousands of people in fourteen languages around the world. Readers can easily find explanations and solutions that speak to the diverse spectrum of developmental levels, learning styles, and abilities inherent in autistic children, at home, at school, and in the community.

Ideas are offered in six domains: Sensory Integration, Communication and Language, Behavior, Daily Living, Thinking Social, Being Social, and Teachers and Learners. The Table of Contents details more than 330 subjects, making it easy to quickly pinpoint needed information.

- Accessible ideas that don’t require expensive devices or hours of time to implement.

- Relatable ideas and solutions to situations that most parents, educators, and/or family members will recognize.

- Functional ideas that help prepare the autistic child for a meaningful adulthood.

Awards for 1001 Great Ideas:

- Winner of the Eric Hoffer Book Award for Legacy Nonfiction

- Winner of the American Legacy Book Award for Education/Academic

- Winner of the American Legacy Book Award for Parenting and Relationships

- Silver medal, Independent Publishers Book Awards

- Gold award, Mom’s Choice Awards

- Finalist, American Legacy Book Awards, Cross-genre Nonfiction

- Teachers Choice Award, Learning magazine

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 611

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

1001

Great Ideas

for Teaching & Raising Children with

Autism

Ellen Notbohm | Veronica Zysk

1001 Great Ideas

for Teaching & Raising Children with Autism

All marketing and publishing rights guaranteed to and reserved by:

800-489-0727

817-277-0727

817-277-2270 (fax)

E-mail: [email protected]

www.FHautism.com

© Copyright entire contents Ellen Notbohm and Veronica Zysk, 2004, 2010, 2024

Book design © TLC Graphics, www.TLCGraphics.com

Cover by: Monica Thomas; Interior by: Erin Stark

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of Future Horizons, Inc., except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews.

The information presented in this book is educational and should not be construed as offering diagnostic, treatment, or legal advice or consultation. If professional assistance in any of these areas is needed, the services of a competent autism professional should be sough

Visit the authors’ websites; comments and new ideas always welcomed!

www.ellennotbohm.com, [email protected], [email protected],

Previous edition published as: 1001 great ideas for teaching and raising children with autism spectrum disorders. Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN for E-book Version: 978-1935274-26-1

ISBN for Print Version: 978-1-935274-06-3

Read more than 600 5-star reviews from parents and teachers on Amazon and Goodreads

“A keeper”

"A must-have”

“A life-saver”

“Great reference”

“Great ideas”

“Great explanations”

“Really helps”

“Covers everything”

“Easy to read”

“Easy to understand”

“Incredible resource”

“Definitely recommend”

Acknowledgments

ANY AUTHOR WHO ACCEPTS THE CHALLENGE of putting forth a book of 1001 ideas (or in this edition, nearly 2000 and all of them good, of course) knows it has to be an ensemble piece. We are indebted to the community of outstanding individuals who have enhanced our lives and our book with their expertise, their can-do, will-do attitude, and their devotion to children with autism and the broader world we all share. Through this book, we are but funnels for their collective wisdom and years of effort on behalf of countless children with autism spectrum disorders.

The fingerprints of so many exceptional educators, therapists, parents and friends are all over this book. To name only a few: Greg Jones, Mary Schunk, Julianne Barker, Veda Nomura, Nola Shirley, Lucy Courtney, Diane Larson, Sharon Martine, Marcia Wirsig, Jackie Druck, Terry Clifford, Annie Westfall, Sarah Spella, Robin Jensen, Jean Motley, Arielle Bernstein, Emily Polanshek, and Lacee Jones.

We send heartfelt thanks to the many autism professionals whose work awakened in us reservoirs of ideas we didn’t even know existed. Thanks go to Temple Grandin, David Freschi, Michelle Garcia Winner, Marge Blanc, Jim Ball, Linda Hodgdon, and Lindsey Biel for sharing their knowledge and expertise in ways they might not even have imagined.

Special thanks, as always, to our publisher and friend, Wayne Gilpin, and to our editorial director Kelly Gilpin. We appreciate your unfailing enthusiasm for all our projects.

To our adored parents, whether they are with us in body or in spirit, your presence is the safe haven that gives us courage to venture forth, discover the adventures that lie beyond the edge of our comfort zone, and set that example for others. Your influence is felt daily and only intensifies as time passes.

The significant others in our lives—be they husband, children or friends—have been 150% supportive of our efforts to produce all our books. There is a squirm factor in putting your own experiences and mistakes under a microscope, and they’ve been there for us as cheerleaders, confidants, sounding boards, and critics. You render us speechless—we who are word-smiths—in expressing how important you are to us.

We celebrate every autistic person who has entered our lives, furthering our understanding and our appreciation of their courage, their unique abilities, and their individuality.

ELLEN NOTBOHM

VERONICA ZYSK

Contents

Foreword by Temple Grandin, Ph.D.

Preface

Sensory Integration

Choosing the right sensory activities

Twelve warning signs of sensory overload

To activity and beyond! Fifty ways to get them moving

Learning to enjoy the outdoors

Outdoor bracelet

Summer fun, winter fun

Bring in the great outdoors

Sand table

Sand table activities

The not-so itsy-bitsy spider

A dozen things to do with a refrigerator box

Bathroom sensory activities

Water, water everywhere (they wish!)

Finger painting

Tactile food fun

Bite me: Recipes for edible clay

Child on a roll!

Swinging or spinning

Gross motor activities

Simon-says games

Kid-friendly contact games

Fine motor activities

So all can color

Fidget toys basket

Homemade fidget toys

Hair bbb-rr-uu-sss-hhh?

That sucks! Oral-motor development activities

Balloonarama

Fun with bubbles

The floor is so hard!

Vision and seeing

Larger than life

Figure-ground processing

Sensory survival kits

Teaching self-regulation

Coping with painful sounds

Headphones and earbuds, pro and con

Toe walking

What’s that funky smell?

Do you smell what I smell?

That’s heavy!

The human hamburger

It’s a wrap

Hideout

Bean bags

Comfort first when it comes to clothes

Clothing preferences—both sides now

More on clothes

Sleep on it

Sleep tips for road trips

Pre-event strategy

Sensory diet for low arousal levels

Distinguishing between needs and rewards

Hands-on learning

Deep pressure inputs for desk time

Please remain seated

You are now free to move about the classroom

Dealing with “stims” in the classroom

Sensory goals on the IEP

That back to school smell

Your child’s other classrooms

Unsafe, inappropriate, or just annoying?

Communication and Language

Inquiring minds ask

Ask in reverse

Five important words: “I am here for you.”

Does he hear what you hear?

First things first: Get his attention

Jump right in

Feed language in

When speech gets stuck

Beyond single words

Don’t sweat temporary lapses

Visual strategies

Before using that visual schedule

When do we use a visual schedule?

Visual crutches?

Fit the language support to the child’s learning style

Tips for using your visual schedule

Expressive or receptive?

Assistive technology (AT) is more than a keyboard

Environment impacts speech development

Maintaining a language-rich environment

The two-minute rule for conversations

The two-second pause for responses

Snack time: It’s not just about the food

Time to say goodbye

Wordless books

Jump-start literacy for concrete thinkers

Repetitive-language stories

Make reading fun

Raise a reader: What parents can do at home

Say what you mean, mean what you say

You loved the movie—now read the book

Beware of idioms

Go fish for idioms

Phrasal verbs

Homophones

Flash cards: Pros and cons

Not just for tiggers: Trampoline fun

Profanity

Almost as easy as 1-2-3

Blueprint his work

Crossword fun

When out of reach is a good thing

The talking stick

I spy a conversation game

Language in motion

At the movies

Night and day

Communication objectives for an IEP

Reduce your student’s performance anxiety

Help peers understand language difficulties

Why we talk

Asking questions and making comments

With my compliments

The four steps of communication

Behavior

Strengths and weaknesses

Don’t ask why

What we “miss” in misbehavior

Behavior and personality: Consider both

Collaborative discipline

Consequential learning

“I’m angry!”

Sign language: Not just for baseball

Accentuate the positive

Construct a visual barrier

Two-step redirect

Resistant/avoidant behaviors

Hostile or aggressive behavior

Game plan for meltdowns

From bad to worse: How to avoid escalating a skirmish

Peer power and the two-minute warning

Flexibility required

Fun tips to encourage flexible thinking

Beyond the mirror: Memory books and photo travelogues

Helping a self-biter

Please remain seated

The gentle way to criticize

This argument is over

I hear ya—and this argument is over

A token system

Deals and contracts

Watch what you reinforce

Proximity praise

Seasonal interests all year long

Sibling secret knock

“I can’t” time capsule

Proaction versus reaction

More about reviewing behavior

More about enabling behaviors

Just the facts, please!

It was a good day

Daily Living

Matters of choice

Winning isn’t everything?

Just a minute?

Skill development through child’s play

Go ahead—scribble on the wall

Ideas for easing separation anxiety

Tips for happier haircuts

Tips for reluctant shampooers

Nail trimming

Just take a bite

Helpful eating adaptations

Narrow food preferences

Cooking co-ops for special diets

Help for resistant tooth-brushers

Your friend, the dentist

Cuts, scrapes, and bruises

Managing the hospital visit

Help for a runny nose

Potty training

Using public restrooms

Adaptive clothing fasteners

Stepping out

Snappy comeback

Restaurant dining, autism-style

Moving to a new environment

When mom or dad is away

Dress rehearsal for special occasions

To hug or not to hug

Shared sibling activities

Equal sibling time

The newspaper: Window on the world

Happy birthdays start here

A cake by any other name

Uncommon gifts for uncommon kids

Gift-getting etiquette

Frame it

Autism safety

Safe in the yard

Home safety for escape artists and acrobats

When your child isn’t sleeping

Relax through breathing

Explaining death to the child with autism

Change only one thing at a time

Help the medicine go down

A little more help

Spray vitamins

Reduce allergens, prevent ear infections

Medications: Be thorough

Start an autism book circle

So many books, so little time

I can do it myself—the preschool years

I can do more myself—as children grow

I can do a lot of stuff myself—the older child

You can do it yourself—the reluctant child

Guiding your child with autism to adulthood

Thinking Social, Being Social

Social referencing skills

Joint referencing

Social stories

Ask him to teach you

Relating to the outside world

Friendships with younger children

Guidelines for developing play skills

Friend to friend

Facilitate playground interaction

First in line—for a reason

Custom board game

Board game adaptations

Toy story

Mine! Mine! Mine!

Teach cooperation through play

Teach cooperation through food

Theory of mind skills

Perspective taking

Understanding emotions

Identifying emotions

Teach intensity of emotion

Separate feelings from actions

Understanding “polite”

Anger management

We can work it out

That’s private

I need a break

When “sorry” seems to be the hardest word

All’s fair?

The appropriate protest

I predict that

Asking others for help

Teaching honesty through example

Everyone makes mistakes

A word about “normal”

Teachers and Learners

It’s good for all kids

Respect the child

Walk a mile in these shoes

Probe beyond the obvious

Avoid teaching compliance

Designated teacher

Small group versus large group

Play to your child’s interests

Shrek’s social card

Privacy screen helps focus

Standing station

Hand fatigue

Body warm-up for classroom work

Houston, we have no problem with transitions

The bridge to circle time

Tips for successful circle time

Integrated play groups

Ready or not—here I come?

Off to kindergarten? Plan ahead

Beginnings and endings

The things-to-do-later bin

Think cultural, think socio

Partnership skills

Choosing a clinician

Choosing an educational program

Review tests

School-bus safety

Auditory processing difficulties

Fire drills—red alert

Teach one skill at a time

Reduce paper glare

Eyes wide open

Participation plans

Teaching concentration skills

Cueing or prompting?

Effective prompting

Is this a teaching moment?

Moments of engagement

Pause and plan

Selecting a keyboard font

What happened at school today?

Introducing new subjects to the child with limited interests

The learning triangle

Bring the outdoors inside

Love your classroom

Reduce clutter

Minimize fluorescent lighting

The whole classroom

Make wall displays meaningful

First-then rather than if-then

Teach fluency/precision

Seeing time

Program accommodations and modifications

Homework homeostasis

Appropriate IEP goals

IEP jargon

Paraeducator-pro

Help for the substitute teacher

Teachers’ rights in special education

Appropriately trained staff

Peer power

Art therapy

Beginning art for the photo-oriented child

Student teacher for a day

Color walk

Phonics hike

Language yes/no game

Name that classmate

Photo reminders

Pair a preferred item or task with something less-than-desirable

Concept formation

A-hunting we will go

What’s your name?

Mirror, mirror

Teach success

Is it okay to visit?

Designed with Asperger’s in mind

When, when, when?

Practice makes perfect

The right write stuff

Easy sports and PE adaptations

A tricycle by any other name

Acclimating to group work

A quick reference guide to successful inclusion

Curbing perseveration

Child on the run

Take it apart

Down with “up”

Down with “down”

Environmental learning preferences

Bridge the gap between schoolwork and “real life”

Use individual interests to promote math skills

Teach math kinesthetically

More math tricks

Teach spelling kinesthetically

My report card for teacher

Summer’s over: Back-to-school strategies

The effective advocate

Mediation alert

Ask these important questions

Creating positive partnerships

Endnotes

Index

About the Authors

Foreword

THE FRONT COVER OF THIS BOOK PROMISES 1001 GREAT IDEAS, which is an ambitious undertaking by itself. The back cover of this second edition promises 1800. Anyone browsing autism books might question that two authors could amass this many ideas and that all of them would be “great,” but I must say, this book delivers. It is crammed full of helpful ideas that parents and teachers can immediately put to use to teach children with autism.

During my childhood years my mother and teachers utilized many of the methods discussed in this excellent book. They recognized that when it came to teaching a child with autism, creativity, patience, and understanding, as well as an inexhaustible quest for ideas and strategies that made sense to me, were the key to helping me become the independent, successful person I am today. However, my journey from childhood to adulthood was not without its obstacles, and I’d like to share some of my experiences to demonstrate what a difference ideas can make in a person’s life.

I was lucky to be surrounded by a supportive team of adults from almost the very beginning. Excellent educational intervention, which began at age two-and-a-half, was crucial for my success. The most important aspect of my early intervention was keeping my young brain “connected to the world.” My typical day included speech therapy, three Miss Manners meals (where table manners were expected), and hours of turn-taking games with my nanny. I was allowed to revert to repetitive, autistic behavior for one hour after lunch, but the rest of the day I participated in structured activities.

I was nonverbal until age three-and-a-half, but even after that time, speech therapy was a very important part of my intervention. When adults spoke to me in a speedy, everyday manner, their words sounded like gibberish, so naturally I could not respond appropriately. All I heard were vowel sounds—consonant sounds dropped out. But when people spoke slowly, directly to me, I could understand what they were saying. My speech teacher carefully enunciated the hard consonant sounds in words such as “cup” or “hat” until I learned to listen for and eventually hear those types of sounds.

Playing turn-taking games occupied a major part of my day before I went to kindergarten at age five. Initially, taking turns was a real challenge for me. But daily games and other activities drilled the concept into me. Board games such as Parcheesi and Chinese checkers were a couple of my favorites. To enjoy playing them, I had to learn to wait for my turn.

Turn-taking was also taught with outdoor activities such as building a snowman. I made the bottom ball, then my sister made the middle, and then I made the head. My nanny had a box of “snowman decorations,” which was full of old hats and bottle caps that could be used to make eyes and noses. We had to take turns putting these things on the snowman’s head. I also had to learn to take turns in neighborhood games, such as skipping rope. Two people swung the big rope while one person jumped. I had to learn that I could not be the jumper all of the time. I had to let others jump sometimes when it was my turn to swing the rope. Turn-taking was further emphasized in conversation at the dinner table. I was allowed to talk about things that interested me, but I was taught to allow my sister and others to take turns talking.

Learning those functional life skills concepts early helped me a great deal when it was time to start elementary school. Yet I believe the structure of the classroom itself was particularly conducive to my learning style. It was an old fashioned 1950s classroom with only twelve or thirteen students per class, where everybody worked quietly on the same thing at the same time. If I had been placed in a noisy, chaotic classroom with thirty students, like too many modern classrooms, I may not have done so well.

Many other factors contributed to my success in elementary school, but there were two factors that helped me the most. First, my teachers educated my classmates about my differences. They not only explained the nature of my challenges, but they also taught my peers how to help me. The second key to my success was the close collaboration between mother and my teachers. The rules for behavior and discipline were the same at home and at school. If I had a temper tantrum at school, the penalty when I got home was no TV that night. The rules were very clear and there was no way I could manipulate my mother or the teachers to change the rules or the consequences. Be sure to differentiate between a tantrum (voluntary) and a meltdown (involuntary, usually due to sensory overload or being over-tired). Tantrums warrant consequences, but meltdowns usually indicate that accommodations are needed.

Nowadays, classroom accommodations and modifications are common, and even mandated by law. Therapists and teachers’ aides have become integral to Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). There weren’t any teachers’ aides in my school, but if I had been put in a larger classroom, an aide would have been essential.

Some of the most common accommodations necessary for children with autism are those that address sensory challenges, and this book provides a great deal of insight into this topic. Sensory issues in autism are really variable, yet problems in these areas can cause real pain and major meltdowns. They range from a mild nuisance to being extremely debilitating. Children can have auditory, visual, and/or tactile sensitivity—or under-sensitivity in any or all of those areas. Tactile sensitivity was one of my worse problems. For example, I could not tolerate being hugged, and wool clothes felt like sandpaper against my skin.

Like many children, my sensory issues were not limited to one sense. When I was in elementary school, the sound of the school bell hurt like a dentist drill hitting a nerve. There are some individuals who have such severe sound sensitivity they cannot tolerate public places such as malls and supermarkets. Another problem with those types of places is the constant flicker of fluorescent lighting, visible only to people who are visually sensitive. Pale-colored glasses and Irlen-colored lenses have helped many children avoid sensory overload in over-stimulating places. To my knowledge, the most effective colors are pale pink, lavender, purplish brown, and pale brown.

Visual sensitivity can be equally overwhelming at home and school. To avoid harsh fluorescent lighting, it may be a good idea to move the child’s desk over by a window, or put a lamp with a 100-watt light bulb next to his desk. Do not use compact fluorescent bulbs because many also flicker. Certain types of computer screens can flicker as well. LCD screens on laptops do not, so consider letting a child use an old laptop with an external keyboard and mouse instead of the school computers. Even paper can be visually offensive. If a child complains that words wriggle around on their paper, try printing the child’s work on pastel-colored paper to reduce contrast. Let the child pick the color.

Throughout this book, the authors address these same areas of challenge—language and communication, behavior, functional skills—and offer countless more sensory ideas and accommodations. I found the “Adaptations at home” and “Adaptations at school” sections on pp. 30-32 to be particularly helpful. You will also find lots of good tips for promoting healthy personal hygiene. Too often these important lessons are overlooked until the child is older and hygiene problems become more noticeable. I appreciate that the authors emphasize an overall healthy lifestyle; it’s a consistent theme. Getting plenty of exercise really helped me when I was a child. My mother used to say to me, “Go outside and run the energy out.” Scientific research continues to reveal the numerous neurological benefits of exercise, including the great calming effect it can have on people.

It is important to address children’s physical needs first and foremost to create a comfortable environment where they can learn. A child who hurts or has painful gastrointestinal issues is not able to absorb learning and benefit from treatment programs. Once those needs are met, I can’t stress enough the importance of helping children develop their individual talents and strengths. My area of strength was drawing, and that became the basis of my livestock facility design business. My caregivers and educators provided me with tools to get started, such as a book on perspective drawing and art supplies, and then helped me expand my abilities through concrete lessons and remaining positive. They had that “can do” attitude reflected all through this book.

Like many other children with autism, I got fixated on certain subjects and sometimes needed prompting to try new things. For example, I loved drawing pictures of horses, but one day, my mother asked me to do a painting of a beach. She rewarded me by framing my painting. The authors of this book share hundreds of similar ways to think creatively in working with a child. To broaden children’s fixations, teachers and parents must help children develop their special interests into abilities that others people value. Having a career, or even a job you’re good at, can foster confidence, independence, and a lifetime of rewards.

As I was reading through this book, my mind was flooded with pictures from my childhood. So much of the wisdom of this book is timeless; some things just work whether it’s 1950 or 2010. Simple games such as skipping stones on a pond were some of my favorite activities as a child, and I think they can become part of other children’s fond memories as they grow.

In addition to the thousands of concrete ideas and activities, the authors offer genuine, commonsense advice that all parents and educators can quickly and easily use and appreciate, no matter what your level of experience with spectrum children. The advice on how to handle the dreaded trips to the doctor and the dentist is alone worth the price of the book!

1001 Great Ideas will become your go-to book as you support the child with autism in your life. Easy-to-read sections, full of bulleted tips, provide innovative solutions to infinite types of situations. The authors even carry their ideas one step further, offering extra suggestions for customizing the content to your child or student’s needs.

If every school and family used even some of the ideas in this book, the possibilities for improving the lives of children with autism would be limitless. And that’s what I call great.

— TEMPLE GRANDIN, PH.D.

1001 Great Ideas for Teaching and Raising Children with Autism Awards

Winner of the Eric Hoffer Book Award for Legacy Nonfiction

Winner of the American Legacy Book Award for Education/Academic

Winner of the American Legacy Book Award for Parenting and Relationships

Grand Prize Short List, Eric Hoffer Book Awards

Silver medal, Independent Publishers Book Awards

Gold award, Mom’s Choice Awards

Finalist, American Legacy Book Awards, Cross-genre Nonfiction

Teachers Choice Award, Learning magazine

Authors’ Note

“A day can go forever, but the years fly by” is a truism for many parents raising autistic children.

And so it has been for us and this book. As we write this Authors’ Note today, 1001 Great Ideas is marking its 20th anniversary. Year after year, it has reached millions of readers in 14 languages and won many awards.

The timelessness of the thoughts and guidance that make up 1001 Great Ideas is the key to its longevity and popularity within the autism community. Still, change has inevitably been afoot in the autism world in those twenty years. We acknowledge the following:

Vocabulary and language usage among both autistic and nonautistic people have evolved over the last several decades, and it will continue evolving to reflect growing knowledge, differences in cultures, individual preferences. No single format can represent all. At the time this book was written, the term “with autism” was standard and used to acknowledge the person apart from their diagnosis. Today, “autistic” is preferred by many. This may change yet again over time. We consider the terms autistic, with autism, with ASD (autism spectrum disorder), and on the spectrum to be interchangeable. Please “translate” in your head per your personal preference.

We recognize that the term Asperger’s is no longer a part of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual and no longer used to describe autistic persons. This book uses she/her and he/him, but we recognize and honor all gender preferences. This language too is likely to evolve over time.

We are forever grateful to the many readers who have forged connections with us, sharing their stories of how our book helped them shape their relationships and experiences with their autistic children, family members, teachers, and friends. What a joy it is to now enter this 20th anniversary year, welcoming a new generation of families to the adventure ahead.

Ellen Notbohm

Veronica Zysk

Preface

WHETHER OR NOT YOU BELIEVE IN FATE, karma, or serendipity, an impetus greater than mere coincidence brought the two of us authors together. Veronica had been an autism professional for more than a decade, the head of a national autism organization, a Vice President for our publisher, Future Horizons, a book editor and Managing Editor of the Autism Asperger’s Digest, the first national magazine focused solely on autism spectrum disorders. All these things—but not a parent. On the other side of the continent, Ellen was the parent of two sons, one with autism and one with ADHD, a writer and communications consultant—but with no professional autism credentials. Forces were set in motion when Ellen submitted an article about her son’s tussles with literacy to the Digest. Over the course of the ensuing year, conversation after conversation ended up in the same place: our vastly different experiences dovetailed beautifully to form a remarkable partnership. Many collaborative ideas got kicked around for months, and then came the opportunity to write this book together.

Our shared beliefs and values pervade our writing, and you won’t be able to miss them because they distill down to three elements on which we are very clear.

Sensory integration is at the core of our rubric. It drives both of us berserk that some folks in the field of autism still view sensory integration therapy as an as-time-allows add-on to “real” treatments, and when we hear from parents and professionals who regard it as unscientific hogwash or teachers who never, ever incorporate it into their classroom strategy. Is it because the topic is so intensely complex that many simply turn away from it, hoping for an easier solution? Such an attitude is certainly understandable. Neurology is a very, very complicated proposition. Katharine Hepburn in The African Queen provides us with the definitive approach. When the German officer protests that her journey down an unnavigable river is impossible, she responds: “Never. The. Less.”

Never in your parenting or teaching experience will it be more important to do whatever is necessary to put yourself in the shoes—in the skin—of another, especially one whose sensory systems are wired so differently. The child experiencing hyper-acute sensory responses to his world is in a state of constant self-defense against incessant assault from an environment that is spinning, shrieking, squeezing, and defying him at any given moment. To expect social or cognitive learning to take place under such conditions is simply unrealistic to us, thus we place major emphasis on sensory integration. You’ll see it throughout the book—in just the same manner that sensory inputs pervade real life not just for children with autism, but for all of us. For the child affected this way, sensory therapy must be the cornerstone of any treatment program. We know this because we’ve seen it up close in many children. As a preschooler, Ellen’s son exhibited extreme tactile, oral, aural, visual, and proprioceptive defensiveness. After seven years of focused sensory intervention, he was dismissed from both occupational therapy and adapted PE programs because his skills and sensitivities in these areas were no longer distinguishable from those of his peers. It wasn’t magic. It was sensory intervention. Sustained, patient, sensory intervention.

Shoulder to shoulder with sensory intervention is the significance we place on communication and language therapy. There simply can’t be any argument that a child who cannot make his needs known and thereby met is going to be a simmering cauldron of frustration and despair. Research in the early part of the decade suggested that 40% of our children with autism are nonverbal, and that a majority of these children will never develop functional language. We just don’t agree, and that incites us to be vocal with parents and professionals about the importance of giving children—all children—on the spectrum a means of communication. Whatever form it takes—sign language, PECs, assistive technology, verbal language or any combination of these or other options—what is critical is that the child has what constitutes a functional communication system for her. Imagine going through your day unable to keep pace, comprehend, or contribute to the conversation around you, not possessing the means or the vocabulary to tell your boss or mate that you hurt or need or want, being unable to decode the symbols on a page or the sounds coming out of a telephone. As with sensory integration, when either receptive and/or expressive language is obstructed, the day becomes a minute-to-minute struggle to merely cope; no true learning can take place in such an environment. Doug Larson tells us, “If the English language made any sense, a catastrophe would be an apostrophe with fur.” Any speech language pathologist or English Language Learner teacher will tell you that English is arguably the most treacherous language on the planet. For concrete thinkers like our kids with autism, the English language, with its inconsistent rules, abstract idioms, nuances of sarcasm, homophones, multiple-meaning words, and seemingly nonsensical words like pineapple (which contains neither pine nor apple) is a desperate morass. Early, intense, and ongoing language/communication therapy is crucial and, happily, it is an area where a little awareness enables adults to make a difference at every hour of the day. We’ve included hundreds of ideas in this area so you can do just that.

Overreaching all of this is our most heartfelt conviction that the ultimate power to live with and overcome autism lies in our willingness to love the child or student with autism or Asperger’s absolutely unconditionally. Only when we are free of “what-if?” and “if he would just...,” will we have a child who himself is free to bloom within his own abilities (he has many), his own personality, and his own timeline (not ours or what is “developmentally appropriate”). It is no less than you wanted for yourself as a child, and it is no less than what you want for yourself as an adult. A child who feels unconditional acceptance and perceives that the significant adults around truly believe “he can do it” has every chance of becoming the happy, competent adult we always hoped and dreamed he would be.

In the years since we published the first edition of this book, we have between us, as authors, co-authors and editors, worked on many more books, some of which have risen to the top of the autism category and remained there, many winning multiple prestigious awards. In all the books on which we collaborated, the messages of this, our original book, remain consistent. The ongoing popularity of 1001 Great Ideas coupled with years of amassing new ideas demanded that we create this second edition—a significantly updated and expanded version of the original work. You’ll find far more than the 1001 ideas the title claims, as we delve more deeply into complex subjects like social thinking, language/communication, and the adult’s role in shaping a child’s behaviors. We also explore topics not addressed in the original work.

Autism is an edifying experience, if you will let it be so. Each day you embrace its presence as part of your life is another day of understanding it and your child, and integrating that wisdom into your collective experience.

The gift of a rich and meaningful life for you and your child with autism awaits you.

1

Sensory

Integration

There is no way in which to

understand the world

without first detecting it

through the radar-net of our senses.

DIANE ACKERMAN

OF ALL THE BAFFLING ASPECTS OF AUTISM, perhaps none is more baffling to the layperson than sensory integration. Sensory integration is the ability to process and organize sensations we receive internally and externally. Sensory input travels to the brain through our neural network, where it is interpreted and used to formulate a response. Sensory processing happens without conscious thought; it operates in the background and most people never stop to ponder how their senses function or the part they play in daily life.

There are as many as twenty-one sensory systems at work in our bodies. Most of us recognize the traditional five: sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. Five other senses are commonly attributed to humans: equilibrioception (our sense of balance or vestibular sense), proprioception and kinesthesia (sensing the orientation and motion of one’s limbs and body in space), nociciption (pain), temporal sense (sense of time), and thermoception (temperature differences).

Through a complex series of atypical signals/connections between the sensory organs and the brain, the child with autism or Asperger’s experiences sights, sounds, touches, smells, tastes, and gravity in a manner profoundly different from that of typically-developing children and adults. Every minute of daily life for a child on the autism spectrum can be a battle against invasive sensations that overwhelm their hyper-acute sensory systems. Or conversely, their senses may be hypo-active, requiring major effort to alert their bodies so that learning and social interaction can take place. Layered on top of that may be an inability to filter and process more than one sensory modality at a time.

Step for a moment inside the body of a child with sensory integration difficulties in this excerpt from Ellen’s book, Ten Things Every Child with Autism Wishes You Knew:

My sensory perceptions are disordered. This means that the ordinary sights, sounds, smells, tastes and touches of everyday that you may not even notice can be downright painful for me. The very environment in which I have to live often seems hostile. I may appear withdrawn or belligerent to you but I am just trying to defend myself. Here is why an ordinary trip to the grocery store may be hell for me:

My hearing may be hyper-acute. Dozens of people are talking at once. The loudspeaker booms today’s special. Musak whines from the sound system. Cash registers beep and cough, a coffee grinder chugs. The meat cutter screeches, babies wail, carts creak, the fluorescent lighting hums. My brain can’t filter all the input and I’m in overload!

My sense of smell may be highly sensitive. The fish at the meat counter isn’t quite fresh, the guy standing next to us hasn’t showered today, the deli is handing out sausage samples, the baby in line ahead of us has a poopy diaper, they’re mopping up pickles on aisle 3 with ammonia—I can’t sort it all out.

Because I am visually oriented, this may be my first sense to become overstimulated. The fluorescent light is too bright; it makes the room pulsate and hurts my eyes. Sometimes the pulsating light bounces off everything and distorts what I am seeing—the space seems to be constantly changing. There’s glare from windows, too many items that distract me (I may compensate with tunnel vision), moving fans on the ceiling, so many bodies in constant motion. All this affects my vestibular sense, and now I can’t even tell where my body is in space.

We have said in all our books and will say it again here: sensory integration dysfunction is at the root of many of the core difficulties of autism spectrum disorders. It affects behavior, communication, nutrition, and sleep—critical functions that dictate the quality of the environment your child must live in, minute to minute, day to day, year to year. Addressing and treating sensory dysfunction should always be near the top of the what-to-do-first list.

There are two over-arching thoughts to keep in mind when considering the thousands of aspects of your child’s sensory integration needs.

First, sensory training can look and feel like play. Play is the medium through which children learn. Play puts fun into functional, grabs a child’s attention, and holds his interest. An engaged brain is a brain ready to learn. The wonderful thing about sensory training is that opportunities and learning moments happen all around you at any time of day, at home, at school, out in the community.

Second, your school may offer occupational therapy support, and/or you may contract with a private agency outside of school, but those hours are finite and few. Consistent, ongoing sensory integration therapy happens at home. Placing your child in the hands of a professional for a few hours a week is the beginning—an excellent beginning—but the bulk of the work will come in the home setting. If this seems daunting, go back and read the previous paragraph. It can also be playful.

All the sensory ideas in our book come with the caveat that there is no substitute for working with an occupational therapist who is well versed in autism spectrum disorders. He or she will provide the foundation of knowledge that helps you better understand how senses are impaired by autism or Asperger’s, can set up a sensory diet for your child (a daily plan of stimulating and/or calming activities), and tweak the plan as you discover what works and what doesn’t.

Believe—really believe—that no child wants the negative or punitive feedback he gets for his so-called “bad behavior,” especially when those inappropriate behaviors are beyond his control, rooted in the dysfunctional way his sensory organs and his brain communicate. Regulating over- or under-active senses is an essential first step in helping the child master socially acceptable behavior. This achievable and worthwhile process requires patience, consistency, and an ever-watchful eye for discerning sensory triggers. Start slowly and stay the course.

Choosing the right sensory activities

Sensory integration activities should be fun for your child or student. Follow these guidelines:

Choose activities in which your child can lead, guide, or direct the play This is the first step in his later being able to initiate a play activity, with you or others.

When you find something that works, share it across other venues of your child’s life. Consistency between home and school enhances retention, will maximize his success, and with it, his self-confidence.

In choosing age-appropriate activities for your child, remember that there may be gaps between his chronological age and his developmental age. The right activity accommodates his skill level and current sensory and social tolerance threshold. Example: mixing cookie dough is a great sensory activity, but having two or three friends/siblings/helpers in the kitchen at once may be too much. The activity may be successful only as one-on-one time with Mom.

Any activity that can comfortably incorporate family members is a bonus. But ...

Activities should not impose excessive burdens on the family budget, schedule, space, or patience. There is such thing as too much. The beauty of so many sensory activities is that just a few minutes here and there can have a cumulative effect over time.

We’ve amassed many ideas for sensory activities that you can incorporate easily into your child’s day. Some of the ideas are appropriate for both home and school; all are designed to get you thinking beyond the traditional activities that might initially come to mind.

Twelve warning signs of sensory overload

Ideas in this book and others, as well as suggestions from your occupational therapist and other professionals, offer myriad ways to enhance your child’s over- or under-stimulated sensory systems. Your child will embrace some, others not.

It is natural to want your child to engage in enjoyable sensory activities “to the max,” but is more better? Emphatically no, say occupational therapists. Too much of a good thing can overload delicate senses, triggering that dreaded meltdown. Familiarize yourself with these twelve warning signs of impending overstimulation:

Loss of balance or orientation

Skin flushes, or suddenly goes pale

Child is verbalizing “Stop!”

Child steadfastly refuses activity

Racing heartbeat, or sudden drop in pulse

Hysteria, crying

Stomach distress: cramps, nausea, vomiting

Profuse sweating

Child becomes agitated or angry

Child begins repeating echolalic phrases, or some familiar non-relevant phrase over and over again (self-calming behavior)

Child begins stimming (repetitive, self-calming behaviors)

Child lashes out, hits, or bites

If any of these occur, stop the activity at once. Your child’s behavior is telling you the activity is too much to handle. Resist the urge to think your child “should” be able to handle it, or handle it just a little longer. Consult your occupational therapist as to how often and how much of the activity he or she recommends, and ways to create a more appropriate sensory diet for the child.

To activity and beyond! Fifty ways to get them moving

Physical activity is critical to any child’s overall health, and the social interaction that takes place during such pastimes can be beneficial too. All physical activities provide your child with multi-sensory input—opportunities to retrain the brain and help their sensory systems function more as they should. With repeated practice, fine and gross motor skills will get better, even with more impaired children. Individual or group movement activities help build coordination, motor-recall, muscle-memory, control, and spatial awareness. They teach timing, predicting, following/reacting to directions, and adapting to changes. Physical and social feedback can motivate children to work through the initial awkward learning stage and experience success. When they do, you’ll also see self-esteem skyrocketing.

In exploring physical activities for your child, liberate yourself from any constraints you may have as to what constitutes a legitimate sport. Although many children with autism or Asperger’s enjoy soccer, basketball, and baseball, team sports are not for everyone. Myriad rules can be confusing, the jumble of bodies upsetting, the auditory and olfactory sensations overwhelming, and the expectations of team members stressful.

Some parents (not you, of course) are of the mindset, often to the detriment of their child, that Chase isn’t playing a real sport unless he’s on the school football team. As a concept, it simply isn’t true. Our kids can excel at various activities when given the chance, proper guidance, and gradual exposure. And there is a lot to be said for seeking out the less populated sports. Many children thrive in the “big fish in a small pond” environment these sports offer. They may be much more welcoming of beginners, even offering sample courses or mini-lessons. If they don’t, explain your situation and ask about it. The worst that can happen is they say no, and the manner in which they say no will give you an idea of whether or not your child will be welcomed there. So if the concept of competition is too challenging for your child, let it go for now. There is every possibility he may grow into it later, and if not, building an association of physical activity with fun has a much more profound life impact.

Where you live will partially dictate your choice of activity. Denver denizens may find surfing difficult to pursue; ditto for aspiring skiers in Miami. But it’s never an excuse for the truly motivated. Remember the 1988 Olympic Jamaican bobsled team? They were the masters of adapted sports, outfitting their bobsled with wheels to practice in their tropical locale. What everybody remembers about them is their spunk and their sense of fun, not that they finished last. Six years later in Lillehammer, they in fact finished ahead of both USA teams in the four-man event.

The list below suggests many ways to enjoy sports and physical activity outside the typical arena of team sports. There is no magic about the list; it’s comprised of regular activities that have been around forever.

How to choose? Before trying something new, give some thought to how an activity matches your child in the following ways:

Interest level. Don’t force your child into something that doesn’t appeal to him. Start with high interest areas that will be naturally motivating and rewarding.

Energy and affect level. A low energy child might find frisbee or yoga perfect, but basketball or tennis too upsetting for her system.

Muscle tone and coordination. Both can improve over time with engagement, so start out at an easy pace and build from there. Take a walk around the park a few times before venturing off on a four-mile hike.

Individual, two-person, or team activities? Your primary goal is regular movement and fun exercise. A no-stress enjoyable bike ride around the neighborhood with just you may engage her more than a dance class with several other kids.

Fun versus winning. If your child just can’t stand to lose, steer him to non-competitive, individual sports. There’s no win/lose angst involved in fishing, hiking, rock climbing, etc. And keep in mind that in many children with autism or Asperger’s, the concept of competition is not readily present, but must be taught. Is the angst about winning possibly coming from you?

Use technology to create a bridge from home to outdoor or group activity. Rent a few martial arts, exercise, or dance DVDs to test them out with your child.

What we want to impress upon you here is that abundant possibilities exist and to not overlook the obvious when you’re planning for physical recreation. Pursued at an individual pace, these activities may give your child more room for growth and achievement than he had before, bettering your chances for both success and enthusiasm. In the marathon of life, isn’t that real success, after all?

Water sports: swimming, swim lessons, swim team, synchronized swimming, aquacise for kids, diving, surfing/boogie boarding, rowing, canoeing, rafting, fishing

Fun on wheels: Big Wheel, tricycle, bicycle with training wheels, two-wheeler, alley cat, tandem, scooter, roller skates, skateboard

Racket sports: tennis, racquetball, handball, badminton, ping-pong (table tennis)

Take-aim sports: bowling, golf, miniature golf (putt-putt), archery

Running/walking/jumping: kids’ biathlon or triathlon, jogging, trampoline, hiking, track and field events

Snow sports: downhill skiing, cross-country (Nordic) skiing, snowboarding, tobogganing, snow-shoeing, ice skating (figure or speed), ice fishing

Martial arts: tai chi, tae kwon do, karate, judo, aikido, kick-boxing, capoeira

Equestrian: horseback riding, kids rodeo

Play activities: jumping rope, hop/jump balls (handle on top), hula hoops, tether ball, pogo stick, jai-alai (scoop-toss games), or Velcro

®

-disk catch games, lawn or floor hockey, Frisbee

Coordinated movement: tap dancing, ballet, hip-hop or ethnic dance, jazz or modern dance, yoga, baton twirling, gymnastic/tumbling, rock climbing. (Look for non-competitive studios that focus on fun rather than skilled competitions.)

Learning to enjoy the outdoors

Nature is its own classroom, filled with awe-inspiring sights, sounds, tactile sensations, and smells. Even though your child may have sensory sensitivities, it’s important that he be exposed to new experiences to develop, grow, and even become less sensory defensive. The key is in slow and measured contact, using his reactions as your gauge.

Quiet nature settings are most conducive to your child having a good experience. Get away from the constant noise and echoes of the cityscape, the omnipresent electronics, the pervasive visual clutter and hordes of people— the sense of “ahhh” will be tangible for everyone. Go to a park in the early morning quiet, find a small babbling stream, or a field with tall grass. Look for interesting rocks to take home. Take a blanket and spend the afternoon looking for pictures in the clouds, or counting the birds that fly by. Take a woodland/nature walk: identify ten things you see, ten things you hear, ten things you can touch, ten things that are fuzzy, or hard, or bendable. Explore! (See also A-Hunting We Will Go in Chapter 6.)

Outdoor bracelet

Sturdy sticky duct tape is the beginning of a neat outdoor bracelet. Tape it sticky-side-out around her wrist and let her fill it with sticks and leaves, sand and shell bits, grass and flower petals. Note: Will she melt down when you cut it off later? Make the loop big enough that she can slip it off her hand, or fold ends and secure with a paperclip on her wrist for easy undo later.

Summer fun, winter fun

Reinterpret some of your favorite summer activities for winter. A few to get you started:

Get out the sand castle molds and make snow castles instead; packed snow behaves much the same as packed wet sand.

Use rectangular food storage containers to make bricks for forts and igloos.

Write messages or draw pictures in the snow with a stick. Take a photo of your message (“I love Grandma”) and put it in a photo snow globe as a special gift to a loved one. (Photo snow globes are available at craft stores and photo/electronics sections of some stores, especially at holiday time.)

Is your child a

Cat in the Hat

fan? Mix a few drops of red food coloring in a spray bottle and spray the snow pink, like Little Cats A, B, C, D, and E.

A tire swing left over from summer is good for snowball-throwing target practice.

Or use that tire swing to let go and land in a mound of snow.

Practice that tennis or baseball swing with snowballs. If it splats, you know you hit it.

Get out that slippery-slide and ice it down; use it as a bowling lane or shuffleboard alley.

Remember: Children with autism or Asperger’s are frequently insensitive to temperature. Since they won’t tell you when they get too cold, keep checking to make sure they are properly protected at all times.

Bring in the great outdoors

Some kids don’t enjoy the great outdoors because they come in contact with so many things that, to them, are dirty or yucky Acclimate them slowly and at their own pace by bringing the outdoors in. A small wading pool on your kitchen, bathroom or mud-room floor can be a mini-ecosystem. Dirt, sand, twigs, rocks, pinecones, nuts, seed pods, a square of sod, can all be shoveled, sorted, stacked, and otherwise manipulated from a safe spot in her inside world. She can wear plastic gloves to touch things at first. As they become more familiar to her, she may find it easier to transition to enjoying them outdoors.

Sand table

Sand play is great for stimulating the proprioceptive sense, which activates through input from joints. For variety, alternate filling the table with:

Rice (a few drops of food coloring can add interest)

Beans/lentils

Kitty litter (the kind made from ground nut shells, corn, recycled newspapers or wood, other green materials)

Potting soil or dirt

Popcorn (unpopped or popped)

Birdseed

Oatmeal, bulgur, millet, other grains

Home aquarium rocks

Pea gravel

Sand table activities

There’s more to sand table play than scooping sand, filling buckets and dumping it out again. Important sensory and motor development in eye-hand coordination, vestibular sensation, and proprioception are inherent in these activities. They offer opportunities to teach opposite concepts, such as in/out, here/there, or full/empty Help children explore the terrain through activities that require them to push/pull/drag/dig on a repeated basis:

Dig for hidden objects

Combine with water play, especially to change the texture of the material.

Play with action figures or animal figurines. They can march, crawl, jump— whatever keeps them moving through the substance.

Play with construction vehicles—making hills and roads, and digging holes.

The not-so itsy-bitsy spider

Your little Spiderman will enjoy turning his room or playroom into a life-size web with a ball of string, yarn, kite string, or unwaxed dental floss. Wrap the string around doorknobs, dresser knobs, bed legs, chair spindles, anything sturdy. Have him crawl, climb through, and otherwise navigate the maze. At the end of the day, give him scissors to cut his way out.

A dozen things to do with a refrigerator box

Children often love the large box something comes in more than the item itself. For your child with autism or Asperger’s, oversized boxes are the beginning of many wonderful sensory-therapeutic experiences. Many kiddos on the autism spectrum enjoy enclosed spaces like closets, cubbies, and hidey-holes. A large appliance box is ideal. Adapt a refrigerator box to your child’s interests and needs.

Make a quiet place. Paint the inside a calming color and furnish with pillows, books, stuffed animals, headphones, and music.

For the outer space aficionado, cut star shapes in the top.

For the tactile-input seeker, line the insides with favorite textured materials such as fur, corduroy, sandpaper, etc. Or fill pockets with textured items (marbles, seeds, etc.). Hang clear vinyl shoebags for inexpensive ready-made pocket space.

Some kids bliss out on bubble wrap—imagine a whole “room” lined with it.

Paint the interior with chalkboard paint and he can change the landscape whenever he feels like it.

A small-screen TV or DVD player turns a simple box into a movie theater.

A sleeping bag and flashlight make it a campsite.

Open your own restaurant. Your picky eater may even surprise you and sample something new. Don’t forget to practice ordering and paying the check.

Install a steering wheel. He’s a race car driver, a bus driver, a truck driver, fireman, or pilot.

Staple silky fabric on the ceiling and sides, put a rug on the floor, and add some pillows. Your caravan princess can daydream to her heart’s content.

Line the inside of the box with reflective paper and hang a disco light or one of those multi-colored Christmas tree toppers from the ceiling. It’s like being inside a kaleidoscope. (Use caution if the child has strong visual impairments.)

Language lesson: create games that teach the spatial vocabulary and concepts. This version of Simon Says emphasizes spatial terms: “Simon Says go

inside

the box. Shake your foot

outside

the box. Hide

behind

the box. Run

around

the box. Throw the beanbag

over

the box.”

Bathroom sensory activities

Bath time is sensory time! Capitalize on this everyday opportunity to calm and soothe the hypersensitive child, or to give additional sensory stimulation to the hyposensitive child.

Play with kitchen implements such as basters, colanders, ladles, funnels. An old rotary eggbeater and some liquid bubble bath, baby bath, or dish soap combine for a fun sensory exercise. Whip up a bowl of bubbles, a towering tub of suds, a wading pool full of froth, and a ferocious shark, or magical mermaid.

Add food coloring to cups of water.

Introduce textured items such as a bath mitt, washcloth, loofah sponge, back brush.

If your child likes the scent of peppermint, chamomile, or other herbal tea concoctions, give her a few tea bags to steep in the tub with her.

After the bath or shower, towel-dry him or her with lots of pressure.

Rub body lotion on his or her arms and legs (only if the child enjoys it—and can tolerate the scent).

Brush teeth with a battery-operated toothbrush.

Water, water everywhere (they wish!)

Many children on the spectrum are fond of any kind of water play with its many textures, temperatures and smells. That may be good or not-so-good, depending on your child. Stay attuned to aspects that might interfere with the overall experience and make it unappealing.

Washing dishes, especially in soapy water up to his elbows

Playing in mud: thick and oozy or thinner and grainy

Filling water cans and watering garden flowers

Playing in puddles—stomping (especially with bare feet), stirring with a stick, tossing in pebbles

Washing the car or bike or dog with bucket or hose

Playing with a water wiggle or other toys that hook up to a sprinkler or hose

Floating on a raft or inner tube

Diving for objects (weighted rings, coins)

Finger painting

Most of us fondly recall this favorite childhood activity as a chance to get our hands squishily messy in an appropriate way. That good sensory feel to us might not feel so good to your child or student. Introduce finger painting to a tactile-defensive child in gentle increments. Start by letting him use a cotton swab. Then move to rubber or plastic gloves (such as food service gloves). As he becomes more comfortable, cut off the fingertips of the rubber gloves— one at a time (for instance, per week), if necessary.

QUICK IDEA

Commonly used sensory rewards can lose their luster quickly. Test the appeal quotient of a sensory reward often. If it no longer holds the child’s interest, it’s no longer rewarding.

You needn’t spend major money on finger paints. You can make easy-mix, non-toxic paints from ordinary household ingredients, and your child may be more interested in the activity if he participates in creating the paint. Make a simple paint by combining equal parts flour and water, then adding food color. Or, dissolve one part cornstarch in three parts boiling water, adding glycerin for shine (monitor the temperature closely as it cools and don’t let little fingers dip in until safe).

Finger painting outside can be especially fun if either you or your child worry about mess. He may enjoy painting on leaves or rocks instead of paper. As interest grows, introduce substances that differ in texture and viscosity, such as shaving cream, pudding, or bath gel. Mixing in rice, cornmeal, or grits adds another layer of sensory input.

And, think beyond fingers: paint with feet or toes or even elbows.

Tactile food fun

Even for the child who doesn’t like to get his hands dirty, helping you make a snack or part of dinner might be an acceptable way to experience tactile sensations. (And it’s never too early to start teaching everyday life skills.) Try these ideas:

Mixing/patting/rolling out cookie dough by hand

Mixing guacamole by hand, including mashing the avocado with fingers first

Beating pudding or pancake batter with a rotary beater

Mixing cake batter by hand with a whisk

Churning butter in a jar until it firms up

Creating cookie shapes in dough with cookie cutters or with a cookie press

Kneading bread dough

Making figures out of marshmallows or gum drops; joined by pretzel sticks or toothpicks

Bite me: Recipes for edible clay

Clay and play dough are great sensory experiences, unless you spend the time taking your child’s hand away from her mouth as she tries to eat the stuff. Make her day—with edible clay.

Note: Do not use these recipes if your child is allergic to peanuts.

Recipe #1: Combine 1 cup powdered milk, 1/2 cup creamy peanut butter, 1/2 cup honey. Spray your child’s hand with non-stick cooking spray and set her loose. She can eat the shapes she makes now or refrigerate for later. Adding pungent spices like cinnamon or nutmeg brings another sense to the experience.

Recipe #2: Combine 3 1/2 cups creamy peanut butter, 4 cups powdered sugar, 3 1/2 cups light corn syrup, 4 cups powdered milk.

(Recipes adapted from SurprisingKids.com)

Recipe #3: Chocolate Play Clay. Melt 8 oz. semi-sweet chocolate in a double boiler. Stir in ¼ cup plus 1 tablespoon corn syrup. The mixture will stiffen, but keep stirring until combined. Transfer to a plastic bag and refrigerate until firm. Knead pieces until pliable enough to shape (or eat). Use sparingly, as ingesting too much can bring on stomach upset in some children.

QUICK IDEA

The same daily sensory factors that affect a child—lighting, smells, sounds, colors, temperature, visual stimuli—can affect the accuracy of assessments and the effectiveness of therapy. Practitioners: Be sensory sensitive in all arenas.

Child on a roll!

Rolling can be a delightful whole-body experience for your child—up or down or across different textures. Watch for signs of dizziness, nausea, or disorientation—warning signs that sensory activity is too intense—and be ready to stop immediately. Kids can roll:

On the grass: on level ground or down a hill, and then he can crawl back up the hill on his tummy

On the carpet: thick and plush, sisal, or indoor/outdoor

While inside a blanket: wool, cotton, fleece, velux, thin or thick

While inside a large box: cut off top and bottom to form a tube

Swinging or spinning

Many kids with autism or Asperger’s love to spin and swing. Occupational therapists and speech-language therapists frequently work together as language often emerges while children are swinging or involved in some fun large movement activity. Be creative with swinging and spinning.

Regular playground-type swing

Hammock or net swing

Tire swing

Platform swing (carpet- or foam-covered plywood sheet)

Pipe/bolster swing (fabric-covered large, capped, plastic pipe) they can lie over stomach-down

Trapeze