Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

1971 was a great year for cinema. Woody Allen, Robert Altman, Dario Argento, Ingmar Bergman, Stanley Kubrick, Sergio Leone, George Lucas, Sam Peckinpah, Roman Polanski, Nicolas Roeg and Steven Spielberg, among many others, were behind the camera, while the stars were also out in force. Warren Beatty, Marlon Brando, Michael Caine, Julie Christie, Sean Connery, Faye Dunaway, Clint Eastwood, Jane Fonda, Dustin Hoffman, Steve McQueen, Jack Nicholson, Al Pacino and Vanessa Redgrave all featured in films released in 1971. The remarkable artistic flowering that came from the 'New Hollywood' of the '70s was just beginning, while the old guard was fading away and the new guard was taking over. With a decline in box office attendances by the end of the '60s, along with a genuine inability to come up with a reliable barometer of box office success, studio heads gave unprecedented freedom to young filmmakers to lead the way. Featuring interviews with cast and crew members, bestselling author Robert Sellers explores this landmark year in Hollywood and in Britain, when this new age was at its freshest, and where the transfer of power was felt most exhilaratingly.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 613

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

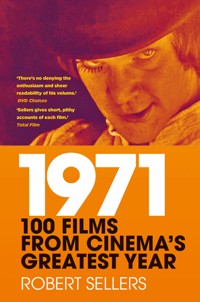

Front cover image: Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge in Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film A Clockwork Orange. (Wikimedia Commons)

First published 2023

This paperback edition first published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Robert Sellers, 2023, 2025

The right of Robert Sellers to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 492 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

100 Films

1Performance

2Murphy’s War

3The Music Lovers

4The Last Valley

510 Rillington Place

6Little Murders

7The House That Dripped Blood

8Death in Venice (Morte a Venezia)

9The Emigrants (Utvandrarna)

10When Eight Bells Toll/Puppet on a Chain

11Get Carter

12THX 1138

13Lawman

14Dad’s Army

15Vanishing Point

16The Andromeda Strain

17The Beguiled

18Just Before Nightfall (Juste Avant La Nuit)

19Taking Off

20Melody

21Trafic

22Summer of ’42

23Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

24Bananas

25Murmur of the Heart (Le Souffle au coeur)

26Billy Jack

27WR: Mysteries of the Organism

28Blue Water, White Death

29The Abominable Dr. Phibes

30Escape from the Planet of the Apes

31Big Jake

32Daughters of Darkness

33Carry On Henry

34The Ceremony (Gishiki)

35The Anderson Tapes

36Willard

37Klute

38Wild Rovers

39Le Mans

40McCabe and Mrs Miller

41Shaft

42Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory

43Drive, He Said

44Carnal Knowledge

45Walkabout

46Sunday Bloody Sunday

47Two-Lane Blacktop

48The Panic in Needle Park

49Blood on Satan’s Claw

50Godzilla vs. Hedorah

51The Devils

52Johnny Got His Gun

53The Hired Hand

54Villain

55The Omega Man

56The Decameron

57Let’s Scare Jessica to Death

58The Touch

59Beware of a Holy Whore (Warnung vor einer heiligen Nutte)

60The Big Doll House

61A Bay of Blood

62Out 1

63The Go-Between

64Company Limited

65Monty Python’s And Now for Something Completely Different

66The Last Movie

67Kotch

68The Last Picture Show

69Blanche

70The French Connection

71Wake in Fright

72Punishment Park

73Twins of Evil

74Hands of the Ripper

75Play Misty for Me

76The Big Boss (Táng Shān Dà Xiōng)

77A Fistful of Dynamite (Duck, You Sucker!)

78Fiddler on the Roof

79Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde

80Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb

81200 Motels

82Bedknobs and Broomsticks

83Mon Oncle Antoine (My Uncle Antoine)

84Duel

85Two English Girls (Les Deux Anglaises et le continent)

86A Touch of Zen (Xia Nu)

87Straw Dogs

88Man in the Wilderness

89Nicholas and Alexandra

90Bleak Moments

91Family Life

92Gumshoe

93The Hospital

94Macbeth

95Four Flies on Grey Velvet

96A Clockwork Orange

97Harold and Maude

98Mary, Queen of Scots

99Dirty Harry

100Diamonds Are Forever

The Good, the Bad and the Weird: The Best of the Rest

Notes

Select Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Vic Armstrong, Michael Attenborough, John Bailey, Derek Bell, Tony Lo Bianco, Erika Blanc, Michael Brandon, Timothy Burrill, Don Carmody, Kit Carson (2010 interview), Diane Sherry Case, Tom Chapin, Joan Churchill, John Cleese (2003 interview), Brian Clemens (2011 interview) Michael Deeley (2014 interview), Norman Eshley, David Foster (2010 interview), Clive Francis, Robert Fuest (2011 interview), Ellen Geer, Richard Gibson, Bruce Glover, Katherine Haber, Piers Haggard (2012 interview), John D. Hancock, Peter Hannan, Jo Ann Harris, Mike Higgins, Mike Hodges, Julian Holloway, Eric Idle (2003 interview), Henry Jaglom (2010 interview), Michael Jayston (2011 interview), Terry Jones (2003 interview), Tony Klinger, Hawk Koch, Harry Kümel, Valerie Leon, Mark Lester, Stephen Lighthill, Tom Mankiewicz (2010 interview), Michael Margotta, Kika Markham, Tom Marshall, Judy Matheson, Murray Melvin (2013 interview), John Milius (2004 interview), Donna Mills, Sofia Moran, David Muir, Danielle Ouimet, Tony Palmer, Anne Raitt, Alvin Rakoff, Angharad Rees (2011 interview), Anthony B. Richmond, Christian Roberts, Ken Russell (2005 interview), Ilya Salkind, Peter Samuelson, Christopher Sandford, Peter Sasdy (2011 interview), Jerry Schatzberg, Julio Sempere, Carolyn Seymour, Ralph S. Singleton, Mel Stuart (2011 interview), Michael Tarn, Damien Thomas, Beverly Todd, Patrick Wayne, Stephen Weeks, Michael Winner (2010 interview), Deborah Winters.

INTRODUCTION

What is the greatest year in movies? I guess there will never be a definitive answer. It’s all subjective of course. There’s no single greatest anything really – no greatest film, no greatest song, no greatest painter, no greatest football player. It’s always going to be a question of personal taste and opinion. But, as I’m the one writing the book, I guess my opinion holds sway, and in my opinion 1971 is pretty hard to beat.

Just take a look at some of the filmmakers plying their trade in 1971 – Roman Polanski, Woody Allen, Steven Spielberg, Stanley Kubrick, Sam Peckinpah, Luchino Visconti, Sergio Leone, Peter Bogdanovich, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Robert Altman, George Lucas, Dario Argento, John Schlesinger, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Nagisa Ōshima, Ken Loach, François Truffaut, Miloš Forman, William Friedkin, Joseph Losey, Mike Nichols, Mario Bava, Nicolas Roeg, Louis Malle, Ken Russell, Satyajit Ray, Jacques Tati, Mike Leigh and Ingmar Bergman. Can any other year match that amount of creative talent on display?

And if it’s stars you want, how about John Wayne, Marlon Brando, Clint Eastwood, Steve McQueen, Paul Newman, Jack Nicholson, Jane Fonda, Dustin Hoffman, Warren Beatty, Al Pacino, Gene Hackman, Bruce Lee, Sean Connery, Michael Caine, Richard Burton, Peter O’Toole, Richard Harris, Julie Christie, Faye Dunaway, Dirk Bogarde, Anthony Hopkins, Goldie Hawn, Robert De Niro, Albert Finney, Burt Lancaster, Charlton Heston, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, Raquel Welch, Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave?

What was the state of play in 1971? Well, it was all change. As usual the British film industry was in a state of flux, but this time it faced falling off a precipice. The American studio money that had been pumped into British films during the heyday of the 1960s had virtually dried up. It was always a dangerous situation to have one’s indigenous industry dependent upon outside finance. At one time during the 1960s Hollywood was contributing over 80 per cent of the finance for British film production. This was never sustainable – and so it proved. Film producers now faced finding finance from new sources and the scarce few independent British companies around. Luckily, there was enough product already in the pipeline to make 1971 a healthy-looking year for British movies; but this really was the last hurrah. The rest of the decade resembled something of a wasteland until the industry picked itself up again in the 1980s.

Hollywood was changing too. It was the last embers of the studio system. The studios still wielded enormous power, but they were like dinosaurs, out of date and out of time. Some faced bankruptcy and had to sell off their backlots to property developers to stay afloat or sell out to non-media companies. Michael Margotta was a young actor under contract then to Columbia:

You could still feel the ghosts of the past. There was an executive dining room and if you went up to have lunch there you could still feel the atmosphere of what it was like before, when Harry Cohen ran the place and the executives couldn’t sit down until he sat down.1

This old guard was fading away and a new breed was on the march. The old guard knew it too. With a decline in box office attendances, along with an inability to recognise what audiences wanted to see, studio heads gave unprecedented freedom to younger writers and directors to make the kinds of film they wanted to make. This was really the start of the ‘New Hollywood’ that was to result in a decade of remarkable filmmaking. But it’s perhaps in 1971 that we see it at its freshest, that the transfer of power can be felt most exhilaratingly.

Much of the richness of the films of 1971 is due to the political and social situation of a USA still coming to terms with the political assassinations of the Kennedy brothers and Martin Luther King, along with the continuation of the Vietnam War that had led to unrest and riots on college campuses around the country. A lot of films tapped into this mood and embraced the spirit of the counterculture, while others clung desperately onto the tenets of the past.

It also helped that this movement coincided with the continuing decline in censorship, which had stifled the industry for decades, ushering in an explosive age of sex and violence on screen. The British censor perhaps suffered its most contentious and controversial period during 1971, dealing with such hot potatoes as A Clockwork Orange, Straw Dogs, Get Carter and The Devils.

What may be most striking about 1971 is just how many firsts there were. Steven Spielberg made his first feature-length film, Duel, which aired as an ABC TV Movie of the Week in America and received a theatrical release in Europe. George Lucas made his feature debut too, with THX 1138, a chilly dystopian vision of the future that is worlds away from Star Wars.

Clint Eastwood made his directing debut with Play Misty for Me. The year 1971 must rank as Eastwood’s busiest and most significant year, as it also saw the release of The Beguiled, and the iconic Dirty Harry. As San Francisco police detective Harry Callahan, Dirty Harry spawned a five-film franchise, and gave birth to some of the most quotable movie lines in history: ‘Do you feel lucky, punk?’ and ‘Go ahead, make my day.’ His arrival on screens came just two months after the introduction of another iconic cop, Gene Hackman’s Jimmy ‘Popeye’ Doyle in The French Connection.

In Melvin Van Peebles’s landmark independent movie Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, the police are painted as a force of oppressive white supremacist power. The extraordinary success of Baadasssss Song, combined with Gordon Parks’s Shaft, with Richard Roundtree as a Black private eye, initiated the blaxploitation genre that would flourish over the course of the next half decade. There was a boom in martial arts pictures too, starting in 1971 after the financial success of Bruce Lee’s first starring role in The Big Boss. Meanwhile, Mario Bava’s A Bay of Blood laid down the ground rules for every ’80s slasher movie to come.

1971 really has everything, from Godzilla to spaghetti westerns, Monty Python to Hammer horror, Carry On to Giallo. That’s why, for me, it stands out from any other year in movie history, just by virtue of the sheer variety of films on offer. What other year could possibly serve up both Harold and Maude and Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory?

Notes

Release dates pertain to the movie’s country of origin. For example, if it’s a British film, the release date in Britain is the one given. If the film is a co-production, then it’s usually the earliest release date that is noted. Release dates are courtesy of the American Film Institute and the Internet Movie Database.

100 FILMS

1

PERFORMANCE

This is a film that straddles two decades and two different worlds. Made in 1968, it’s very much a comment on what was happening as the 1960s began to draw to a close. It was a swansong to that most brilliant decade, and an introduction to the 1970s. Shelved by Warner Brothers, scared and repulsed in equal measure by its contents, it finally opened in the summer of 1970 in the USA, but British audiences didn’t get the chance to see it until the start of 1971. Launching the career of its co-director Nicolas Roeg, Performance pushed the boundaries of British cinema in terms of explicit sex and drug use, and made a studio executive’s wife vomit into her handbag.

The whole thing began as a star vehicle for Mick Jagger. The man chosen to bring it to life was painter-turned-filmmaker Donald Cammell. His story idea was, ‘what would happen if a London gangster stepped into the very different world of a rock star?’ This was the Kray twins meets the Rolling Stones. By the 1960s the East End thug had become almost a celebrity in his own right; the likes of the Krays hung around the fringes of showbiz, owned clubs and nightspots, and cultivated the friendship of stars. In Performance, Chas is a particularly vicious London gangster who is forced to go on the run when he murders one of his own. He finds refuge in a vast townhouse occupied by a reclusive and faded pop star called Turner, played by Jagger in his first film role. Slowly Chas’s identity is broken down, as he is subjected to psychedelic drugs and mind games.

Cammell wanted Marlon Brando to play Chas, but in the end cast James Fox. As part of his research Fox visited Ronnie Kray in Brixton prison. However, it was the participation of Jagger and the prospect of tapping into the youth market that enticed Warners into supplying the £400,000 budget. Roeg, an acclaimed cinematographer, joined Cammell as co-director when shooting began in August 1968. The exterior of Turner’s mansion was shot in Notting Hill, while the interiors were in an altogether different house that was found by the production team. This house was in the process of being renovated, which made it perfect to create the claustrophobic and bohemian rooms that Turner inhabited. According to Peter Hannan, who was on the camera unit as focus puller, this house was situated just off Sloane Square. Hannan has fond memories of the shoot. Roeg had personally asked him to do it and the two later became good friends. Hannan would later shoot Roeg’s Insignificance (1985), along with films like Withnail & I (1987). At close quarters Hannan observed how Roeg and Cammell complemented each other in the unusual dual role of director: ‘Donald would rehearse the actors in the green room or any room he could find, but the visuals were Nic. They worked really well together.’1

As for working with Jagger, who had no previous acting experience, Roeg told Hannan, ‘If they’re a star, they’re an actor.’ This was something he said about David Bowie too, when he cast him in The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976). Initially, Jagger had no discipline. Hannan says:

He’d say his lines and walk off the set, still saying his lines. He didn’t know where the shot started or where it finished. But he was very good. Between set-ups, quite often he would just be sitting on a chair or a stool singing beautiful blues. He was an amazing blues singer.2

Hannan noticed a lot of hangers-on all over the set, girls that Jagger knew. There was also ‘super groupie’ Anita Pallenberg, who had previously dated Brian Jones, was currently going out with Keith Richards and reportedly had an affair with Jagger during the shoot. Then 26, Cammell asked her to appear as the strong-willed girlfriend of the washed-up Turner. Jagger’s real-life girlfriend, Marianne Faithfull, had been approached to play the role, but she was pregnant at the time.

Performance conveys a vivid sense of the criminal underworld of London, probably because there were actual bona fide villains involved, like John Bindon. He’d fallen into the acting game when director Ken Loach spotted him holding court one night in a Fulham pub and cast him in his working-class drama Poor Cow (1967). Hannan recalls:

I became quite close to John Bindon. Quite often we’d meet for a drink. Sometimes we’d go to a pub in Fulham, his home manor: ‘Let me introduce you to the lads,’ he’d say and point, ‘This one’s carrying, carrying, not carrying, cop, cop, carrying’, and when he said ‘carrying’ it meant he had a gun on him.3

Another pub Bindon frequented was the Star Tavern in Belgravia. Hannan says:

There was an upstairs bar, and they’d all be crooks up there. But as long as you were with Johnny you weren’t in any trouble. He was well respected by the lords and ladies of this world, people like Princess Margaret.4

Famously, when Performance was unveiled at a test screening for Warner executives it was a disaster. They hated it. ‘At those executive screenings, once somebody doesn’t like it, no one likes it,’ claims Hannan. ‘They all agree with each other. They’re all yes people.’5 Shocked by the more permissive elements in the picture, its dense storyline and the decadent behaviour of the characters, Warners refused to release the film in its present state. Cammell took off to Los Angeles to recut it, changing things around a bit, reducing the violence and sex and the insinuation of a relationship between Turner and Chas. At another test screening the alleged throwing-up incident took place, forcing it to be halted. It would take Warner Bros another eighteen months to gather up the courage to release it to the American public and then finally to the UK.

Performance did find a loyal audience, but it was never a commercial success. Only later did it build a reputation and the kind of cult status that few films manage to acquire. Numerous books have been written about it, along with academic theses. It certainly left its mark on a few of the participants. Fox would later admit that it had been a traumatic film to make. In a way, he felt like the character Chas, this straight actor thrown into a maelstrom of personal anguish and extreme drug-taking. He’d be sitting there on the set with the script every morning, studying his lines, while his co-stars deliberately walked around smoking joints to piss him off. Shortly afterwards, Fox left acting altogether to become a Christian evangelist. He didn’t make another film until 1978. Others affected were Pallenberg, who emerged from it all a heroin addict, and Cammell, who took his own life in 1996. ‘He was a very interesting man,’ says Hannan.6 His was a unique talent, although he only managed to make three further feature films. One of his personal projects was a historical epic about Nelson and Lady Hamilton that would have recreated some of Nelson’s great sea battles. ‘But no studio was prepared to pay for it,’ says Hannan, who was going to work on it. ‘The script was a million pounds a page, really.’7

(UK/US: London opening 7 January)

2

MURPHY’S WAR

By the early 1970s such was Peter O’Toole’s reputation as a hellraiser that, when director Peter Yates and producer Michael Deeley cast him in Murphy’s War, they came up with a cunning plan to keep him under control. Deeley relates:

Because of one’s fear that Peter might be unreliable, pissed out of his mind or something, we decided to cast his wife Siân Phillips to play opposite him. Of course, she’s a great actress, but stuck in the jungles of Venezuela, we thought she would be our insurance. In the event it was totally unnecessary, because Peter behaved with absolute perfection in every way. Actually, he was the glue that held that film together.8

Murphy’s War was based on a 1969 novel by Max Catto, who served in the RAF during the Second World War. It takes place during the last dregs of the conflict, when a British merchant ship is sunk by a German U-boat and the survivors are machine-gunned to death in the water. One of the sailors, Murphy, makes it ashore to a missionary settlement on the Orinoco in Venezuela. Looked after by a nurse, the only female role in the film, he learns that the submarine has taken shelter somewhere up river, and sets about obsessively plotting to sink it by any means.

Peter Yates was a ‘name’ in Hollywood after helming the Steve McQueen crime hit Bullitt (1968), and Deeley’s previous picture was the classic The Italian Job (1969). With such a pedigree Paramount agreed to provide most of the finance. Deeley and Yates were handed a list of ten actors by the studio, and told to make their choice; Paramount’s preference was for Robert Redford. Among the ‘usual suspects’ were a couple of left-field choices, chief among them O’Toole. A Connery or a Lee Marvin would have given a perfectly fine bravura performance, but Yates was aiming for something quirkier than your regular war movie. In that regard O’Toole was the perfect fit.

The movie’s title, Murphy’s War, was a play on the old adage ‘Murphy’s Law,’ which says that anything that can go wrong will go wrong. That certainly summed up the making of the picture. For Deeley, who went on to produce The Deer Hunter (1978) and Blade Runner (1982), Murphy’s War was fun but an enormous challenge, and the toughest film he ever worked on. The location was an absolute killer. Shooting on the Orinoco River, the unit were miles from any kind of civilisation and surrounded by hazards: piranha fish in the shallows and poisonous snakes just about everywhere else. ‘It was a dangerous location because if you fell into the water, you’d be dead. It was that serious.’9 Tracks were cut through the rainforest to location sites only to be impassable again within a week, reclaimed by the vegetation. One night the river rose 15ft, totally submerging one of the sets.

To make matters worse, an old, converted ferry that was going to accommodate the crew got stuck on a sand bank as it approached the mouth of the Orinoco, a mile from the location, demanding the use of small flat-bottomed boats to move everyone back and forth. One morning a party that included O’Toole and Phillips, along with Deeley and his wife, were halfway across when the weather turned bad and the sea began to cut up rough. As Deeley recalls:

The fella who was driving the boat suddenly had hysterics and got down on his knees and started praying. The boat was now completely out of control. Luckily, our stunt arranger Bob Simmons knocked the guy out, seized the wheel and took over. But it was very nasty for a moment.10

O’Toole flourished in the hostile surroundings, living it like some kind of adventure. ‘Peter was the absolute soul of the picture,’ confirms Deeley. ‘And I’ve never seen this with an actor before.’11

Up river, the crew came across a compound owned by a former German officer, who’d clearly decided not to hang around after the war was over for fear of his record emerging. Inevitably, this compound became a frequent destination for drinking and socialising. ‘It was amazing,’ says Deeley. ‘My wife and I were walking down to his hut one night when a huge anaconda wound its way out of a tree into one’s path.’12 It was that kind of place. The officer himself was a genial host, despite being eaten away by leprosy.

After a couple of weeks O’Toole and Phillips were rehoused in a hotel in the nearby town of Puerto Ordaz; a helicopter ferried them into the rainforest for filming. The chopper was manned by a French stunt pilot called Gilbert Chomat, and on weekends O’Toole and Phillips were taken on jaunts round the area, landing on mud banks to search for pre-Columbian artefacts or visiting some of the local tribes.

The scenes involving the burning and sinking of the merchant ship were done later in Malta, at one of the world’s largest exterior water tanks. After his experiences on Lawrence of Arabia (1962), where he had suffered countless injuries, O’Toole decided never again to handle his own stunts: ‘Films employ stunt men, for a reason!’ This changed on Murphy’s War, where in Malta he swam through water filled with burning oil and explosives going off around him and in Venezuela took the controls of a seaplane; his terror-struck face on-camera was not acting.

The gruelling circumstances in which Murphy’s War was made certainly paid dividends on screen, as this offbeat war film is wholly authentic, stunningly shot by Oscar-winning cameraman Douglas Slocombe. O’Toole delivers a whimsical and hard-edged performance, as his obsession to avenge his shipmates turns to madness. Even the discovery that the war is over and the German nation has surrendered doesn’t stop him: ‘Their war … not mine!’

Murphy’s War didn’t fare particularly well with the public or the critics on release. Deeley himself feels the film is flawed due to Yates’s insistence that Murphy be killed off at the end. He survives in the book:

Yates had this passion to make a picture which mattered, but this was not a film which mattered, it was a film which was meant to be a lot of fun, an adventure movie. So, Yates wanted to have this great sad ending, this anti-war message or something, which is such shit, and I think that’s why the picture didn’t do as well as it could have done.13

(US/UK: London release date 13 January)

3

THE MUSIC LOVERS

When Michael Caine wanted Ken Russell to direct the third Harry Palmer feature, Billion Dollar Brain (1967), producer Harry Saltzman wasn’t so sure. A bold talent, to be sure, winning plaudits for his BBC art programmes, Russell had made only the one feature, a black and white comedy called French Dressing (1964). Caine was adamant, however, so Saltzman made a deal that he would bankroll any film of Russell’s choosing if he agreed to make Billion Dollar Brain. Russell accepted and, after the work on it was finished, he turned up at Saltzman’s office to remind him of his promise. ‘Yeah, yeah,’ said Saltzman, asking what Russell wanted to do. ‘I’d like to do a film on Tchaikovsky.’ Russell saw Saltzman grimace. ‘Come back in a week,’ the producer said.

A week elapsed and Russell duly returned. ‘Ok, what about the Tchaikovsky film?’ Saltzman’s face was beaming this time. ‘The Soviets are doing one already,’ he gleefully reported, ‘with Dimitri Tiomkin and he’s already started putting together the score!’14

Russell did finally get to make his Tchaikovsky picture, but not for Harry Saltzman. After the critical and commercial success of his adaptation of the D.H. Lawrence novel Women in Love, United Artists (UA) were keen for Russell to do another picture with them. ‘I said, “Yes, a film on Tchaikovsky.” Their faces fell. They asked what the story was about and I said, “It’s about a homosexual who falls in love with a nymphomaniac.” They gave me the money instantly.’15

Russell’s first choice to play Tchaikovsky was Alan Bates, with whom he’d just worked on Women in Love. ‘But when he read the script, he got cold feet. He didn’t want to play two sexual deviants one after the other.’16 It was Russell’s agent who suggested Richard Chamberlain, then still best known for his role in the hit US television series Dr Kildare. ‘He was the romantic figure everybody expects Tchaikovsky to be who knows nothing about him,’ according to Russell. ‘And I thought he was very good in the film. He played it with just the right touch, the closet homosexual beneath the surface.’17 For Chamberlain it was the biggest challenge of his career to date. As a closeted gay man himself, not coming out publicly until much later in his life, the actor could certainly relate to the need for duplicity and tortured aspect of the composer’s private life.

Melvyn Bragg’s screenplay remains fairly faithful to many of the known details of Tchaikovsky’s extraordinary life, such as his dealings with Nadezhda von Meck, a Russian businesswoman and patron of the arts whose regular financial allowance freed Tchaikovsky to dedicate himself wholly to composition. Most notorious of all was his marriage to Antonina Milyukova. This was no marriage of love, rather one of convenience; for her it was status and money, for him an attempt to both hide and perhaps subdue his homosexuality. As related in the film, the marriage was an immediate disaster, causing Tchaikovsky to have a nervous breakdown and even attempt suicide. Although the couple separated after a few weeks, they remained married, with Antonina continuing to believe in the possibility of some kind of future reconciliation.

For the role of Antonina, Russell cast Glenda Jackson, despite the fact the two of them did not end up on the best of terms after finishing work on Women in Love. By far Jackson’s toughest scene was set in a railway compartment, where she writhes around naked on the floor, bringing herself to ecstasy, as her husband, unable to perform sexually, looks upon her white, lanky flesh with disgust. As Russell cried ‘action’, crew hands rocked the set violently and a champagne bucket, followed by glasses and some cutlery, fell on Jackson, cutting her skin. ‘Wipe the blood off,’ roared Russell, ‘it will never show.’ Next, she was bombarded by heavy luggage. ‘Never mind, get on with it,’ said Russell. ‘The bruising doesn’t show.’ To cap it all, the renowned cameraman Douglas Slocombe, fell right into her lap, managing to splutter, as a way of apology, ‘It’s alright, I’m a married man.’18

Chamberlain found there to be a certain sadism in the way Russell directed this sequence, filming it over and over again. Indeed, he gave serious thought to giving up acting after finishing the film, confessing to the American film critic Rex Reed that he’d never been so depressed and that it took him many weeks to get over it. He admitted to liking Russell, but found him to be excessively demanding in his working methods. ‘It was no fun. That picture nearly put me in a looney bin. But I loved the film.’19

The Music Lovers is typical Ken Russell: controversial, flamboyant, excessive and, in places, quite bonkers. Of all his features on the lives of composers, which also included Gustav Mahler and Franz Liszt, it’s by far the best, and is one of Russell’s most satisfying films. It ends darkly with Tchaikovsky’s death from cholera, after drinking a glass of unboiled water. Was this an error of judgement or, as some have suggested, suicide? As for Milyukova, she spent twenty years of her life in an asylum, diagnosed with chronic paranoia.

(UK/US: New York opening 25 January)

4

THE LAST VALLEY

James Clavell was an interesting figure in cinema. He’d been responsible for the screenplays of such diverse films as The Fly (1958) and The Great Escape (1963). On the strength of his successful adventure novel Tai-Pan, and the film To Sir, with Love (1967), which he both wrote and directed, Clavell had the means to forge ahead with a very personal project, a screen adaptation of J.B. Pick’s historical novel The Last Valley. ‘That was a project he had wanted to do for a long time,’ says actor Christian Roberts. ‘The success of To Sir gave him the opportunity.’20

With its seventeenth-century setting requiring vast warring armies, this wasn’t going to come cheap; it ended up costing almost $7 million. A package was put together by Clavell’s agent, Martin Baum, who also happened to be the head of ABC Pictures, the film division of the US television network ABC. A decision was also made to shoot the picture in the expensive Todd-AO process, becoming the last film to be shot in this process for twenty years.

As befits this kind of historical drama, marquee names were essential and Clavell chose Michael Caine and Omar Sharif. The two met for the first time in a Paris hotel and it didn’t take long for the conversation to turn to the thorny question of billing. Sharif suggested that top billing go to whoever had the fattest pay cheque. Caine agreed. Back in London, Caine discovered Sharif was getting $600,000. Immediately he rang his agent and instructed him to hold out for $750,000. He got it, his biggest fee for a movie up to that time, and grabbed top billing too.

Using a German accent that he later recycled for The Eagle Has Landed (1976), in The Last Valley Caine plays the hard-bitten leader of a band of mercenaries during the Thirty Years’ War, a religious conflict fought in Europe and one of the longest and most brutal wars in history. The mercenaries lay waste to any village they encounter, until they come upon a fertile, idyllic valley, seemingly untouched by the devastation surrounding it. Sharif, as a teacher on the run, has also taken refuge there and aids Caine’s captain in arranging a truce with the local inhabitants, pledging to protect them from invasion in return for food and shelter.

Caine took on the role because it was a million miles away from the cockney strut of Alfie and Harry Palmer. It also said something about war and religion, especially prescient at the time with the troubles in Northern Ireland. For Clavell, the story’s depiction of soldiers pillaging and destroying brought to mind America’s current involvement in Vietnam. Clavell knew something about war. He served as a captain in the Royal Artillery during the Second World War. Captured by the Japanese in 1941, he spent three years as a prisoner of war in the notorious Changi Prison in Singapore, an experience that inspired his first novel, King Rat, in 1962.

For his supporting cast, Clavell brought in an interesting bunch: Florinda Bolkan, Nigel Davenport, Michael Gothard and Brian Blessed. Christian Roberts was just 27 and had played one of the juvenile leads in To Sir, with Love. ‘James was very much a father figure to me as he knew To Sir had changed my life. He was always giving me friendly advice.’21

Filming took place in Austria and the cast were based in a hotel in Innsbruck. Most nights the cast played poker. ‘After winning a few hands Sharif said he would not play anymore as he was a professional Bridge player and it would be unfair,’ recalls Roberts. ‘Caine continued to play.’22 Sometimes the cast would go out to a local club for dinner. ‘On arrival, when they saw Sharif, the band would play the theme song from Dr Zhivago,’ says Roberts. ‘Caine used to say, “Why don’t they ever play Alfie?”’23

Filming was long but enjoyable, except for one terrible incident when the veteran Czech character actor Martin Miller, who had complained that morning about having to shoot in high altitude up in the mountains, suffered a fatal heart attack and died. Work was suspended for the day.

Most of the actors were required to ride a horse, something Caine never cared for. Having stipulated that his horse be small and docile, Caine was more than a bit put out to be presented with the biggest damn horse he’d seen in his life. Despite its fearsome appearance, this, Caine was told, was the calmest out of all the horses. Caine took it for a gentle trot, and all seemed well. On the first day of shooting, he mounted his steed in full costume, only this time it bolted, with the actor barely hanging on to its mane. A jeep followed and finally caught up with them 3 miles distance. Back at the set Caine let rip. ‘I have a filthy temper sometimes, bordering on the psychotic, and on this occasion, I ranted and raved for about ten minutes.’24 It turned out that his character’s sword was slapping against the horse’s side, urging it to go faster.

With an intelligent script and expert direction, stunning photography and one of John Barry’s most majestic scores, The Last Valley did quite good business in Britain. America was a different story, where it was a box office disaster par excellence and no doubt contributed to ABC Pictures ceasing production in 1972 with millions in losses, having never turned a profit.

For Caine, the failure of The Last Valley was one of his bitterest disappointments. He’d given what he thought to be one of his best performances, ‘and all to no avail,’ he wrote in his autobiography. ‘I knew the day we finished it that it was not going to work.’ As for Clavell, he would not direct another feature film. Instead, he returned to writing books, just to see if he still had it. The result was the bestseller Shogun.

(US/UK: New York opening 28 January)

5

10 RILLINGTON PLACE

The infamous serial killer John Christie, who was estimated to have murdered at least eight women, including his own wife, was a role that Richard Attenborough had no real appetite to play when he was first approached about it. And yet he accepted it at once without seeing the script. His friend, the actor and producer Leslie Linder, had been told that an MP was trying to introduce a private member’s bill into the House of Commons to reintroduce capital punishment to Britain, which had been abolished in 1965. Both Linder and Attenborough were firm advocates against capital punishment. Attenborough had been opposed to it all his life, according to his son Michael:

Famously his hero Mahatma Gandhi said, an eye for an eye turns the whole world blind. And that’s what my father believed, that as an act of revenge what you’re doing is stooping to the level of the killer himself. On a purely moral ground he thought it was abhorrent.25

Of all the arguments against capital punishment it was the argument that if you get it wrong there’s no going back that Attenborough found the most convincing. ‘I remember dad saying that you can argue the moral case endlessly, but nobody surely can come up with an argument that justifies hanging the wrong man. And Timothy Evans was the classic case in point.’26

Timothy Evans was hanged in 1950 for the murder of his wife Beryl and baby daughter. The young couple were living at Christie’s squalid tenement at 10 Rillington Place, Notting Hill. Only much later did it emerge that Christie was guilty of the crime and had framed Evans in a bid to cover up what was a killing spree that went back to the 1940s. It was in March 1953, after Christie had moved out of the ground floor flat that he rented, that a new tenant discovered a number of hidden bodies. Christie was caught, tried and executed.

The wrongful conviction of Evans is viewed as one of the great miscarriages of British justice and a factor in the subsequent abolition of the death penalty. In 1961 journalist Ludovic Kennedy wrote his successful book 10 Rillington Place, which subsequently led to a posthumous pardon for Evans. Now it was Linder and Attenborough’s hope that a film of Kennedy’s book might act as a warning against the failings of capital punishment and drown out the voices of those who wished to bring it back.

Having committed to playing Christie, Attenborough carried out extensive research. He read all the reports about the trial, along with pieces written about Christie himself. He met the policeman who arrested Christie, and even visited Madame Tussauds Chamber of Horrors exhibit. All this, and a gruelling daily make-up routine, helped build up a picture of who Christie was, and Attenborough was later to say that never before or since did he become so totally immersed in a role. This had a deeply troubling effect. During shooting he didn’t really speak to anybody and, at lunch, would often sit alone in his dressing room. At the end of the day, he felt uncomfortable going back home to his wife and family, feeling almost ‘unclean’, in his words. Michael recalls:

It’s no coincidence that I visited the set very late on in the shooting. I think my dad felt quite apprehensive about any of the family coming. But having lunch with a man looking and sounding like John Christie was bloody spooky.27

Attenborough had brilliantly perfected Christie’s accent and soft-spoken voice and even off the set continued to use it. This was not unusual; almost with any part Attenborough played the physical or vocal characteristics of the character would often stay with him. Michael reports:

He did a film called Guns at Batasi, in which he was playing a regimental sergeant major, and he used to rehearse all his parade ground shouting and yelling in the cellar. Then when he’d come up and you’d sit down for lunch with him he’d still talk in the manner of a sergeant major.28

Director Richard Fleischer brought the same kind of realism and non-sensationalism to the horrific crimes of Christie that he did with his dramatisation of the life of the Boston Strangler, Albert DeSalvo, a few years earlier in a film starring Tony Curtis. His approach is especially potent in the hanging scene of poor Evans, played brilliantly by John Hurt. This was the first time a British film had recreated an actual hanging, and real-life retired executioner Albert Pierrepoint, who had hanged both Evans and Christie, served as technical advisor to ensure complete authenticity.

10 Rillington Place is a deeply unsettling experience. The fact that the film was shot on the real location adds immeasurably to the pervading atmosphere of evil. The entire street was due for demolition, but the council agreed to pause until filming had been completed. Attenborough would recall how the commotion of a film unit brought so many sightseers and souvenir hunters, taking bricks from the house, that the police were called in. Then, after Fleischer’s crew were finished, the demolition crews arrived, and the area redeveloped beyond all recognition.

It was an unpleasant feeling working inside No. 10, standing on the same floorboards beneath which some of Christie’s victims had lain. However, the bulk of interior shots were completed at No. 7, along with some work at Shepperton Studios. One thing Fleischer does well is to convey the squalor of the area and period. ‘The social and physical conditions of the time were so important to the movie and so important to dad,’ says Michael.29 Despite his fervid anti-capital punishment views, Michael recalls his dad jokingly saying to him one day, ‘I have a feeling I’d hang those who forced people to live in houses like that.’30

Despite the critical favour in which Attenborough was held as an actor, he didn’t like watching himself, so whenever there was a press show he would ask Michael to go in his place and afterwards pass judgement. Attenborough had recently made a film called Loot, based on the Joe Orton play, which came out at the end of 1970. It just so happened that the press shows for Loot and 10 Rillington Place fell within a short space of time of each other. Michael saw Loot first and met his father for lunch afterwards. ‘Look, I’m not going to beat about the bush, you are way over the top. I’m sure you had a great time making it, but it’s an outrageous performance.’31 About ten days later Michael saw Rillington Place and talked to his father as usual afterwards. ‘And I kicked off by saying, “I’m so glad I was honest with you about Loot because I can honestly tell you, and you will be able to believe me, that you were wonderful, extraordinary, terrifying as Christie.”’32

Attenborough always ranked 10 Rillington Place and his own performance among his career highlights, although, according to Michael, it wasn’t a film he liked to talk about. Perhaps he didn’t want to dredge up all those awful feelings he’d had inhabiting Christie. It’s a performance that one is surprised to learn didn’t gain him either an Oscar or BAFTA nomination, although that kind of thing never bothered him. As Michael says, ‘He was never somebody who cared hugely about awards.’33

(UK/US: London opening 29 January)

6

LITTLE MURDERS

Author and celebrated cartoonist Jules Feiffer’s play Little Murders opened on Broadway in April 1967 and, just five days later, closed after a barrage of brutal notices. At one performance there were fewer than fourteen people sat in the audience. The play was inspired by the assassination of John F. Kennedy and, mere days later, the slaying, live on television, of Lee Harvey Oswald. Feiffer viewed this as nothing less than a total breakdown of all forms of authority. The country had descended into madness: it was no longer the place he had been raised in, the rules had changed, something had gone wrong. These feelings were merely heightened when the Vietnam War kicked in. At the time Feiffer felt that no one was really talking about these issues in the way they should have been. At the time he was a cartoonist at The Village Voice, a news and culture paper published in New York. This was far too heavy and complex a subject for a mere six panels of satiric art, and so Feiffer began to write it as a novel. When it dawned on him that he wasn’t a novelist he began to adapt it into a theatre piece and, to his delight, discovered that he was a pretty good playwright.

Feiffer’s comment on the malaise and horror of contemporary America is interpreted through a mismatched New York couple, eccentric photographer Alfred Chamberlain, whose art is photographing piles of dog poo, and idealistic interior designer Patsy Newquist. When she saves Alfred from being mugged outside her apartment, Patsy finds herself attracted to him and tries to find ways to turn him into a suitable husband.

Following its Broadway debacle, Little Murders fared much better on the London stage, where it was the first American play produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company. In 1969, Alan Arkin directed an off-Broadway revival, and this time the play was a success. Maybe the timing was now right. In the face of the recent assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the shootings at Kent State University and a climate of anti-war demonstrations, Feiffer’s satire rang a bit truer. Arkin was also to give the play the right kind of satiric insanity that the original Broadway production lacked.

On the back of this new-found success, Elliott Gould, who had appeared in the ill-fated 1967 production, obtained the screen rights and tried to interest Jean-Luc Godard into directing. This would have marked Godard’s first American production. Feiffer had seen Godard’s surreal road trip film Weekend (1967) and suggested to Gould they try to get him. Godard flew to New York for some meetings, but Feiffer was to recall that it was obvious right from the start that the French filmmaker was there just for a payday from backers UA. Nor did he do much to hide his disdain for the whole lot of them. It was suggested that the screenplay be written by the team of David Newman and Robert Benton, of Bonnie and Clyde fame. According to Godard, UA reneged on the deal he had with them; the studio wanted to keep the Newman/Benton screenplay but ditch him. Maybe the reason was that Godard had totally turned the project upside down and wanted the film instead to be about a French director who comes to New York to make a film called Little Murders but finds he is unable to do it. Goodbye Godard, hello Alan Arkin, despite Arkin never having directed a feature film before. He was also persuaded to play a scene-stealing supporting role as a manic and paranoid detective trying to solve 345 motiveless homicides.

Little Murders is a surreal satire of urban alienation and is among a group of outsider-type movies that came out in 1971, such as Carnal Knowledge, Harold and Maude, Minnie and Moskowitz and A New Leaf. Alfred and Patsy’s relationship plays out against a backdrop of a New York that often resembles an urban battlefield, with random muggings, sniper shootings, garbage strikes and blackouts. There’s a scene where Anthony takes the subway, his shirt covered in blood, and his fellow passengers blithely ignore him, which anyone who has lived in New York can certainly relate to. Several contemporary reviewers commented that Feiffer’s view of urban violence had become more relevant than ever, with noted critic Roger Ebert calling the film ‘a definitive reflection of America’s darker moods’.

Elliott Gould reprised his role of Anthony in the film and, for a while, considered Jane Fonda for the role of Patsy, before casting noted stage actress Marcia Rodd to reprise her role from the off-Broadway revival. Little Murders also reunited Gould with his MASH co-star Donald Sutherland, who agreed to do one day’s work on the film as a favour to his friend. Sutherland plays a New Age reverend that performs Alfred and Patsy’s wedding ceremony.

This is an edgy, risky and frightening comedy. After seeing it, Jean Renoir wrote to Alan Arkin telling him, ‘This film will never be forgotten.’ Unfortunately, largely, it has been. It deserves far more notice.

(US: New York opening 9 February)

7

THE HOUSE THAT DRIPPED BLOOD

In British horror, Amicus were really the only rivals to Hammer’s crown. The company’s headquarters was in a small purpose-built hut on the back lot at Shepperton Studios. It was run by two American producers/screenwriters, Max Rosenberg and Milton Subotsky. Generally, Rosenberg was the least visible of the two, usually away somewhere raising money; it was Subotsky that was more involved on the creative level. Generally, people liked working for them, despite the fact that things were done as cheaply as possible. ‘I would much rather have worked for Amicus than I would for Hammer,’ admits assistant director Mike Higgins. ‘They had a nice production team there; it was a family kind of situation. And it was fun.’34

Ever since the enormous success of Dr Terror’s House of Horrors in 1965, Amicus specialised in the portmanteau film. These typically featured four or sometimes five short self-contained tales linked by a framing device, and their popularity has given them a special place in British horror movie history. Torture Garden followed Dr Terror into cinemas in 1967, and garnered such a lukewarm reception that Amicus didn’t return to the format until The House That Dripped Blood, whose surprise success, especially in America, resulted in a production line of anthologies over the next three years: Tales from the Crypt (1972), Asylum (1972), Vault of Horror (1973) and From Beyond the Grave (1974).

For Dripped Blood Amicus followed the same pattern that was used on Torture Garden: a selection of four short stories from the acclaimed American writer Robert Bloch, the author of Psycho. The framing device is simple yet effective, a Scotland Yard inspector’s investigation into a disappearance leads him to an old house where numerous strange occurrences have taken place.

Another trademark of the portmanteau horror film is its generous use of stars and familiar faces. The House That Dripped Blood is no exception, featuring as it does Britain’s two great horror icons in Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing. The cast also includes Ingrid Pitt, Denholm Elliott and Jon Pertwee, then starring in the title role in television’s Doctor Who. While the film itself took something like five weeks to shoot, actors were only needed for about a week to film their individual episode.

New Zealand-born actress Nyree Dawn Porter, who had recently starred in the BBC’s hugely popular drama serial The Forsyte Saga, appeared in one of the stories. At the time she was suffering from the recent tragedy of her husband dying from an accidental drug overdose. ‘She was a lovely lady,’ remembers Higgins. ‘But she was still trying to get over what had happened and was taking sleeping pills in order to sleep. I was particularly attentive to making sure that she was ok.’35

The most fondly remembered episode is probably the one featuring Pertwee as a horror movie star who buys a cloak for his vampire costume from a mysterious shop, only to discover it belonged to a real blood sucker. This story was a personal favourite of Subotsky. Unlike the rest of the film, this was deliberately played for laughs. Pertwee’s pompous horror star was actually a send-up of Lee. After the premiere Lee, who had enjoyed the segment enormously, approached Pertwee asking who he’d based the character on, totally oblivious that it was him!

During the shooting of the segment, Higgins played a practical joke on the production office when he phoned up Subotsky’s secretary pretending to be from Chipperfield Circus and discussing the possibility of lending them a vampire bat:

I said I was in charge of the bats and before we let it go, we wanted to make sure that they had the correct environment to keep the bat safe. I could hear her getting more anxious as I went on. Then I said, ‘These are rare and delicate creatures from the upper reaches of the Amazon – and they only eat blooooood.’ At which point she ran out of the office in hysterics.36

There are a few neat in-jokes in this segment. One of the vampire cloaks has a label declaring it to be the property of Shepperton Studios, where the film was actually made, and Pertwee’s dressing room is littered with publicity photos, including one of him with Bessie, the famous old car from Doctor Who. Other neat references litter the film, including Lee’s character reading Lord of the Rings, the actor’s favourite book, and the estate agent handling the sale of the doom-laden house is called A.J. Stoker.

As for the house itself, this was actually real and situated in the grounds of Shepperton, although only the exterior was used. The house was later demolished to make way for a housing estate. There was very little location shooting to speak of. A second unit crew were sent out to Weybridge high street, where one of the buildings was mocked up to look like a wax museum for the Peter Cushing story. For one shot the crew wanted to capture normal passers-by and so hid a camera across the street. They began rolling, all seemed fine, until this one woman stopped and began to peek inside the window of the fake wax museum. The first assistant director was stood next to Higgins, picked up a loud hailer and blasted, ‘Heh, lady in the red hat.’ Of course, everybody in the street started looking round. ‘And the lady in question was terrified,’ recalls Higgins.37 The ideal course of action would have been to just let things go; the lady would have got bored and walked on. But no, this bloke blasted out more orders. Higgins says:

Then everybody was rushing about to see where the camera was, and of course it caused absolute chaos and there was the first AD yelling, ‘Don’t move, go away from the window, don’t look at the camera.’ It was chaotic.38

The House That Dripped Blood may not be the best of the Amicus portmanteau films, but it’s a solid example. One of the strangest aspects about it is the virtual lack of any blood or gore. Indeed, the British film censor was all for bestowing it with an A certificate, only for Subotsky and Rosenberg to demand they be given an X (suitable for over-14s), since that guaranteed the usual horror crowd. Subotsky’s stated desire to make a horror picture for younger audiences had perhaps succeeded a little too well.

(UK/US: London opening 21 February)

8

DEATH IN VENICE (MORTE A VENEZIA)

For a long time, Luchino Visconti used to carry around with him a copy of Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice and it was his ambition to one day bring it to the screen. For him, it wasn’t really a tale about death but, as he called it, ‘intellectual death’, an artist’s search all his life for absolute beauty, which he finds in a young boy. This man, who knows he has not long to live, goes to Venice for the last summer of his life and sees in this child the essence of everything that is beautiful and pure; ‘a young god,’ in Mann’s words.

Unfortunately, Visconti could raise only a small portion of finance from Italian sources; the rest of the money he sought in America. This came from Warner Brothers despite them making no secret of the fact that they would have preferred the story to be about a little girl being lusted after, rather than a little boy. Or, as Visconti heard one studio executive say, ‘A dirty old man chasing a kid’s ass.’

For his star, Visconti only wanted Dirk Bogarde; the two of them had recently worked together on The Damned (1969). Visconti likened Bogarde to a dead pheasant, hung from the neck, whose body is ripe. In other words, he was exactly ripe for this role. Bogarde was under no illusion that this would be the biggest challenge of his career. When the script finally arrived four days before filming was due to start, he declared himself to be genuinely ‘scared’.

The film was almost scuppered when Visconti failed to reveal that he didn’t actually own the rights to Mann’s novella. They lay with the actor José Ferrer, who had bought them from the Mann estate back in 1963 with the intention of directing rather than starring, only for him to relinquish the director’s chair to Franco Zeffirelli. Stars like Burt Lancaster, John Gielgud and Alec Guinness all turned the role down, Guinness later admitting it to be among his biggest career mistakes. A deal was finally made for the rights, after several days of anguished phone calls between lawyers, and Visconti’s film was back on.

Bogarde was under no illusion that he was in fact playing composer Gustav Mahler. Others say that the character of Aschenbach is modelled more on Mann himself, who took a similar vacation to Italy in 1911, and there saw a young Polish boy who became the inspiration for Tadzio. Bogarde was made to resemble both Mann and Mahler, with a little moustache and pair of vintage spectacles. His famous white silk suit was also vintage. They were going to put a false nose on him too, but due to the heat it kept falling off. Mann’s protagonist, Aschenbach, is a poet, but Visconti changed him to a composer. This gave him the excuse to memorably fill the screen with Mahler’s lush third and fifth symphonies. When the film came to be screened in Los Angeles, the reception was icy cold. Bogarde and Visconti knew it had fallen flat in the room. There was complete silence. Suddenly one of the Warner executives asked who wrote the music. Visconti told them it was Mahler. Impressed at least with that aspect of the film, the executive pondered whether it was worth putting this Mahler fellow under contract. This story sounds apocryphal, but Bogarde always insisted it happened.

Visconti’s European trek to find the right boy to play Tadzio concluded in Stockholm where he discovered 15-year-old Björn Andrésen. Tadzio is the object of Aschenbach’s yearning, not lust or any other feelings. Bogarde would admonish any reporter who suggested his character was gay. Visconti, too, stated that the love Aschenbach feels for Tadzio was not homosexual, but love without sexuality. Death in Venice would turn Andrésen not into a mere star but an instant icon, his face became the embodiment of youthful beauty. The role completely eclipsed his life. This is a boy who never really wanted to act in the first place; he was much more interested in chewing gum, girls and playing the guitar. Fifty years later he would describe his troubled life in the documentary The Most Beautiful Boy in the World.

Bogarde admired Visconti greatly; best of all Visconti left him alone. They never once discussed the film or the part. Visconti merely told him to read the book. Bogarde did, something like thirty times, but still wanted to discuss it with Visconti, who told him to read the book again. During filming Visconti gave Bogarde just one piece of direction. It was when he was in a boat and Visconti screamed down a megaphone for him to stand up when the sun hit his face. This was because Visconti had already edited the sequence in his head and where the music was going to go. It wasn’t until he saw the finished film that Bogarde realised his movements were being orchestrated in large measure to fit with certain passages of Mahler’s music.