18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

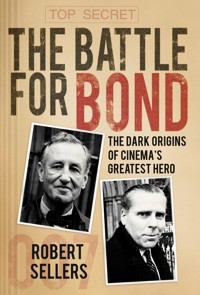

Cinema history was made with the release of Dr. No in 1962. Sean Connery became the face of the suave secret agent 007, and one of film's most iconic franchises was born. How different might that history have been if, instead, Thunderball was the first Bond film to be released, directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Richard Burton as James Bond? It seems absurd, but it almost happened. The Battle for Bond unravels this most controversial part of the James Bond legend using letters and private documents to recount a story in which Ian Fleming found himself in the dock accused of plagiarism, and the events threatened to turn the James Bond film-making world upside down. It is a tale of bitter recriminations, betrayal, multimillion-dollar lawsuits and even death. Regarded within the Bond fan community as one of the most important books ever written about 007, The Battle for Bond was the subject of controversial litigation when it was first published in 2007, and was, for a time, banned in Britain. With this new edition, Robert Sellers revives this fascinating chapter in film history, warts and all.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 483

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

To Martin, my brother in Bond.

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Robert Sellers, 2025

The right of Robert Sellers to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 687 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword by Len Deighton

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 The Irish Maverick

2 The First James Bond Movie Plot

3 Enter SPECTRE

4 The Deal is Done

5 Ian Fleming’s ‘Lost’ Bond Screenplay

6 Looking for a Writer

7 Hitchcock for Bond

8 Enter Jack Whittingham

9 Fleming’s Second Bond Script

10 Money Problems

11 The Search for James Bond

12 The First James Bond Screenplay

13 Disaster Strikes

14 Fleming the Plagiarist

15 Showdown in Nassau

16 Showdown at Goldeneye

17 Six Months to Save Bond

18 Casino Royale Spoils the Party

19 Publish and Be Damned

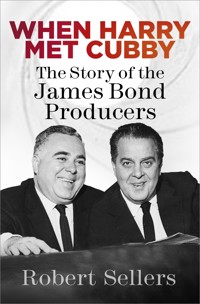

20 Enter Broccoli and Saltzman

21 The Court Case that Killed Ian Fleming

22 Bond Goes Head-to-Head

23 The Forgotten Man

24 Sleeping with the Enemy

25 Eighteen Weeks of Swimming, Slugging, and Necking

26 Beauties and the Beast

27 Bond Hits the Bahamas

28 The Machines Take Over

29 Spearguns and Sharks

30 Back to Pinewood

31 Thunderball Unleashed

32 ‘Warhead’: The Bond Film That Never Was

33 Connery Returns

34 Last Tango in Nice

35 Bahamian Balls-Up

36 The Bitterest Pill

37 McClory Bounces Back

38 The Adventure of a Lifetime

39 The Kidnapping of James Bond

40 Die Another Day

Appendix 1 The Cuneo Memo

Appendix 2 Ian Fleming’s First Script

Appendix 3 Ian Fleming’s Second Script

Appendix 4 Jack Whittingham’s First Screenplay

Appendix 5 Jack Whittingham’s Second Screenplay

Notes

Select Bibliography

About the Author

FOREWORD BY LEN DEIGHTON

Ian Fleming was a delightful companion with a dry sense of humour that was often misunderstood by his critics and notably by reviewers of his books. But the James Bond books were not intended to be comic in any way. Ian chose my first book – Ipcress File – as one of the books of the year but said in passing that he thought thrillers should not be humorous. Later I was lunching at Pinewood Studios with Harry Saltzman when the first public screenings of the first Bond movie, Dr. No, were making the audience laugh. ‘With us, or at us?’ Harry asked anxiously. ‘With us,’ said Harry’s employee, perhaps not wishing to be the bearer of any sort of bad news. ‘Then that’s all right,’ said Harry. From that decisive moment the James Bond movies were to be merry capers and Ian’s strictures set aside. Ian’s starchy English naval officer was played as a Scots-accented comic-strip character to an extent that Sean Connery eventually refused to continue the role. The episodes that Ian said he’d written as autobiography became incredible comedy. It’s as well he didn’t watch it happening. Although a noted wit, Ian was never a joker. Conservative by instinct, he had the determination of Bulldog Drummond coupled with the eccentricity of Bertie Wooster. But he was essentially practical. When he removed his perfectly tailored jacket – which he seldom did – his bare arms revealed short-sleeve shirts; but that was only because Ian hated formal cuffs and fancy cuff links.

The other major role in this sad story is played by Kevin McClory. While Ian was a man who could never have been an actor, Kevin never ceased to be one. I have no doubt that Kevin spent even more money on his suits and shirts and shoes than Ian did, and chose them with equal care. But while Ian was most at home in dark suits, club ties and polished Oxford shoes, Kevin’s light-coloured clothes and unbuttoned silk shirts were in a constantly dishevelled state. And Kevin brought his own disorder with him. I stood with him as he surveyed with apparent surprise his luxury hotel suite in Tokyo. It looked as if it had been vandalised. Around us people urged him to hurry if he was to catch the plane to Okinawa. He turned to the hotel manager and calmly booked the room for another three weeks in order to avoid packing. While Ian had the punctuality that is the mark of the professional writer, Kevin was invariably late – sometimes very late. Sometimes he didn’t turn up at all.

Ian was always cleanly shaven and his hair was always the right length: never too long, never too short. Kevin’s hair was long, white, windswept and wispy. Yet, when I heard someone ask him if it was true that he often flew from his Bahamas home solely to have his hair cut in New York, he didn’t deny it. It was a very special barber, said Kevin. So why not fly the barber to the Bahamas, I asked. Kevin smiled the mirthless smile with which he responded to direct questions. While Ian knew what he wanted, said it and usually did it, Kevin dithered and changed his mind so that people working for him were baffled and frustrated.

Ian had retained the still and inscrutable face that is the necessary part of an Eton education, while Kevin was a professional Irishman with a face that was mobile and florid; if I told you that it was the face of the fairground barker, I’m sure he would not have been offended. And yet both men had the sad-eyed, solemn faces that I have seen on many wealthy men. Were they both chronically unhappy? Yes, I think so – the incurable unhappiness that neither love nor power alleviates. Ian liked games of skill: bridge and golf were his passions. Kevin would play backgammon hour after hour with fierce abandon, and that is a game in which luck and skill are equally decisive. Kevin believed in luck. In Greenwich Village at about 2 a.m., he dragged me into a dark doorway having spotted a lit neon sign that said ‘Fortune Teller’. Having both been given a flattering and optimistic hand reading, he repeated this happy prediction to almost everyone we met over the next few days. Kevin wanted to be lucky and usually he was, but it didn’t make him happy.

Kevin was a rebel in every possible way. He combined spiteful provocation and generosity in equal measure. In restaurants with a group of his friends, I have seen him order food that he knew they would dislike. It didn’t affect him; he had no interest whatsoever in food, while Ian was a fussy and knowledgeable gourmet. Ian, a cosmopolitan linguist, was withdrawn in manner, while Kevin, permanently rooted in Ireland, overflowed with talkative Irish charm. When Kevin gave grand parties in his extensive Irish mansion, he would tell me to bring my mother along knowing how much she would enjoy it, and despite having hundreds of notable guests, he would make time to chat with her.

Both men served in the war. While Ian worked in Royal Navy intelligence in Whitehall, Kevin was a merchant seaman who, after his ship was torpedoed, spent many days in an open boat. Both men had networks of powerful friends, but Kevin’s provocative ways had earned him powerful and dedicated enemies, although his noisy support of Irish Republicanism came more from histrionics than from history. Ian’s chums, associates and supporters came from his London club, from the establishment of bankers, publishers, newspaper management and the aristocracy. Kevin’s companions were luminaries of showbiz, movies and Irish politics. For a confrontation in the London courts, Kevin was at a disadvantage.

Len Deighton

Oaxaca Mexico

2008

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank all those who kindly gave of their time to be interviewed for this book: Sir Ken Adam, Vic Armstrong, Ricou Browning, Earl Cameron, Barbara Carrera, Dick Clement, Len Deighton, Guy Hamilton, Richard Jenkins, Irvin Kershner, Jordan Klein, George Leech, Luciana Paluzzi, Molly Peters, Pamela Salem, Jeremy Vaughan, Sylvan Whittingham Mason and Nikki Van Der Zyl.

Special thanks must go to Sylvan Whittingham Mason. Without her support and efforts this book would not exist. Thanks also for the use of documents from the Whittingham family archive.

Extra thanks go to Mark Beynon of The History Press for resurrecting this book after so many years out of print.

The comeback of the decade: Sean Connery returns as 007 in Never Say Never Again. (Warner Bros/Kobal/Shutterstock)

INTRODUCTION

Cinema history might have been very different had the very first James Bond film not been Dr. No, starring Sean Connery, but instead Thunderball, directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Richard Burton as agent 007. It sounds preposterous and unbelievable, but it almost happened.

The story is the most fascinating, certainly the most controversial, in the entire history of James Bond. It began back in 1958 when maverick Irish film producer Kevin McClory collaborated with Ian Fleming and screenwriter Jack Whittingham on a screenplay entitled Thunderball. Had the project gone ahead, it would have been the first James Bond movie, a full four years before the series started in 1962. But it was never made, and when the audacious enterprise fizzled out Fleming used the screenplay as the basis for his new Bond novel without seeking permission from his co-authors. Feeling betrayed, McClory and Whittingham sued for plagiarism, resulting in one of the biggest media trials of the twentieth century, the outcome of which was to change the screen fate of 007 forever and put the man who created James Bond into an early grave.

McClory walked away from the High Court in London vindicated and with the right to make his own Bond movie. Instead, he joined forces with the official Bond team of Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman to make Thunderball as a one-off joint production. Released in 1965, Thunderball was one of the most financially successful films ever made.

Thanks to his court victory, McClory retained the right to remake Thunderball, resulting in 1983’s Never Say Never Again, which saw Sean Connery return to the Bond role after an absence of twelve years. It was a calamitous production and afterwards Connery lamented the fact that he never killed the producer. No one knew if he was joking or not.

For the next twenty years, McClory fought in vain to launch his own series of 007 films and to have his part in the creation of the screen James Bond recognised. This he did by bringing a massive lawsuit against the Bond makers that had the potential to turn the movie-making world of 007 upside down, and perhaps threaten its very existence.

***

Thunderball is my favourite Bond movie. For me, it epitomises all the best elements of the series: exotic locations, violent action, intriguing women, epic set-pieces, witty dialogue, great music, outlandish gadgets and Connery on top form.

Ever since I started my career as a film journalist and author, I wanted to write a book on Thunderball. However, the journalist in me wanted something more than just an obvious ‘making of’. Then one day, I found it. While googling, I came across a site run by Sylvan Whittingham Mason, the daughter of Jack Whittingham. I got in touch – this was sometime in 2005 – hoping she might talk about her late father and add a personal angle to the whole story. Sylvan turned out to be one of the most generous people I have ever met and was only too willing to help. This offer led to an amazing discovery.

Sylvan told me she had kept all her father’s private documents, including three completed draft versions of the Thunderball screenplay. That was not all. When I arrived at Sylvan’s home, lying on the carpet in the front room were several large cardboard boxes bound by red ribbon, brought in especially for the occasion from safe storage elsewhere. Inside were documents relating to the infamous 1963 Thunderball court case that had been used by the prosecution. McClory’s key lawyer, Peter Carter Ruck, had taken charge of them following the trial and, just before his death in 2003, he passed them on to Sylvan’s safe keeping. Now, here we were, opening them for the first time in over forty years. What secrets would they reveal? What treasures would be uncovered?

Most of what you are about to read, certainly the early section of the book, derives from what we found in those age-stained boxes. Inside were hundreds of private letters written by the main protagonists in the Thunderball saga, principally Fleming and McClory. There was Fleming’s court statement, McClory’s too, which ran for almost 100 pages, Fleming’s two attempts to write a screenplay, pre-production drawings, bank statements, telegrams, location recce reports, and so much else, all revealing hitherto unknown information and truths about this most controversial slice of Bond history.

1

THE IRISH MAVERICK

Ever since James Bond’s literary birth in 1953 with Casino Royale, Ian Fleming dreamed of transferring his hero’s adventures to the silver screen. But each effort met with rejection and disappointment.

It all started so promisingly. On the evening of 21 October 1954, the American network CBS broadcast a live one-hour version of Casino Royale, starring Barry Nelson as 007 and Peter Lorre as the villainous Le Chiffre. Despite the inspired casting of Lorre, the production was a bastardisation of the novel and the character of James Bond, reducing him to an American private detective rather than the suave gentleman spy that readers knew. At one point in the proceedings, he is addressed as ‘card sense Jimmy Bond’.

Top movie mogul Sir Alexander Korda was so captivated by Fleming’s follow-up novel, Live and Let Die, that he called it one of the most exciting books he had ever come across and intended showing it to directors Carol Reed and David Lean for their opinions. British film company Rank then snapped up the film rights to the third 007 novel, Moonraker.

Nothing came of it, nor of Korda’s interest, nor that of Stanley Meyer, the Hollywood producer of hit TV series Dragnet. He wanted an option on both Moonraker and Live and Let Die, but Fleming was asking too much, and the deal collapsed.

In 1956, producer Henry Morgenthau III approached Fleming with the idea of doing an adventure television series for NBC, provisionally titled ‘Commander Jamaica’. Fleming set about writing a pilot episode that revolved around a gang of criminals on an island fortress sending Cape Canaveral missiles off course. When the project inevitably fell apart, Fleming used elements of the plot for his sixth Bond novel, Dr. No.

By 1958, it must have seemed to Fleming that neither the British nor American film and television industries were interested in his James Bond. However, a man by the name of Ivar Bryce was about to change all that.

Bryce had been a lifelong friend of Fleming. The two first encountered each other as children on holiday in Cornwall. Bryce was walking along a beach when he spied ‘four strong, handsome, black-haired, blue-eyed boys’ building sandcastles.1 Invited to join in, Bryce quickly singled out Fleming as the group’s natural leader. The year was 1917 and Fleming was just 9 years old.

The pair renewed their friendship at Eton, finding that they shared common laddish pursuits such as playing truant and meeting girls. Both men were uncommonly attractive. Fleming had a sort of matinee idol attractiveness, while Bryce’s part-Peruvian heritage gave him an exotic look. The writer Cyril Connolly was so taken by the pair that he commented, ‘It would be hard to imagine two more distinguished-looking young men; a Greco-Roman Apollo and a twelfth dynasty pharaoh.’2

Both men came from similar stock too: the upper echelon of British society. Fleming’s father worked for a prestigious banking firm, had considerable private wealth and counted Winston Churchill among his circle of friends. Bryce’s family fortune derived from trading in guano, widely used as a natural fertiliser.

Fleming’s sense of adventure and living life to the full also found resonance with Bryce. Fleming’s greatest fear was succumbing to boredom and, throughout the years, the two friends frequently holidayed together and indulged in numerous escapades. They were always sending letters and cables to each other suggesting some new outlandish enterprise, every invitation closing with the warning: ‘Fail Not’. So close were the two men that Bryce once said of Fleming, ‘There was very little in my life he did not know or share.’3

It was the prospect of getting married at the age of 43, to the former wife of Lord Rothermere, Ann Charteris, and the anticipation of fatherhood (Ann was pregnant) that led Fleming to create James Bond – as a distraction, he said. For his tale, he drew on his own wartime experiences in naval intelligence. Ann largely disapproved of her husband’s creation – an opinion that only marginally decreased as the series of books met with success. She always felt that Fleming should concentrate more on ‘serious’ journalism, such as the work he did for the Sunday Times.

Fleming and Ann honeymooned in Nassau and Bryce met them at the airport. Ann took an immediate dislike to Bryce, considering him a bad influence on her husband. In one letter in 1955 to Lord Beaverbrook, the proprietor of the Daily Express newspaper, Ann wrote of Bryce, ‘It’s a pity Ian’s so fond of crooks, particularly as Bryce is an unsuccessful one.’4

British born but an American resident, Bryce was a financier and philanthropist. Always on the lookout for new avenues to invest in, the movie bug had recently overtaken him after making the acquaintance of Kevin McClory, a young wannabe Irish filmmaker. McClory was something of an adventurer. Before going into movies, according to press reports, he had already driven across the Sahara in a Land Rover in twelve days, tried prospecting for tin in French Equatorial Africa and been a crocodile hunter in the Belgian Congo.

It was his flamboyant personality and zest for life that made McClory popular among the London elite and devilishly attractive to the most glamorous women in Hollywood. Such was his reputation with the ladies that, while working on Around the World in 80 Days, the crew used to call him ‘Around the girls in 80 ways’. He had a brief affair with Elizabeth Taylor and introduced her to her future husband, Mike Todd. He was also romantically linked with Shirley MacLaine. The actress recalled that McClory made a habit of calling her from all over the world, inviting her to do things like go to Bermuda with him to do some skin-diving. He always reversed the charges.

McClory heralded from artistic stock, a descendant of Alice McClory, the paternal grandmother of the Brontë sisters, and his parents were both actors on the Irish stage. Born in 1926 in Dublin, at school McClory didn’t fit in due to crippling dyslexia, although the disability had one advantage, enabling him later to ‘see and write visually for films’.5

Drawn to a world of adventure, McClory joined the Merchant Navy after leaving school in the early stages of the Second World War. On 21 February 1943, his ship was torpedoed in the North Atlantic and, along with other survivors, he managed to scramble into the captain’s lifeboat. For fourteen freezing and terrible days and nights they drifted, with McClory assisting in the burial at sea of eight of his shipmates. When they were finally picked up off the coast of Ireland, McClory was emaciated and suffering from severe shock and exposure. The sole of his boot had burst with the pressure of his swollen, frostbitten feet. Temporarily unable to speak, he spent nine months in hospital recuperating. The experience left McClory with a permanent stammer, but also a new reverence for life.

Unable because of his stammer to find work as an actor, which was his ambition, McClory remained resolute upon a career in films. In 1946, he gatecrashed his way into a £4 a week job at Shepperton Studios as a runner, doing errands and fetching tea for directors. McClory worked his way up in the technical side of the British film industry, becoming a boom operator, location manager and assistant. McClory was location manager on The Cockleshell Heroes (1955), which was produced, ironically, by Albert R. Broccoli.

McClory worked on several pictures directed by John Huston, who became something of a mentor and role model. He was the boom operator on The African Queen (1951), shot on location in what was then known as the Belgian Congo.

Conditions were tough, and there were always three or four people waiting to use the portable toilets. One day, McClory rushed out with his trousers down round his ankles yelling, ‘Black mamba!’ He’d been sitting there when he looked up and saw the snake moving above his head. The crew watched in silence as it slid under the toilet door and into the long grass. Known to be aggressive and highly venomous, the mambas were also known to move in pairs. As Huston recalled, ‘From that moment, all symptoms of diarrhoea in camp disappeared.’6

McClory worked for Huston again on Moulin Rouge (1952) but really endeared himself to the director on Moby Dick (1956). Some filming took place in the ocean in the Canary Islands, using a massive working model of a whale constructed out of metal, wood and latex that was secured by a cable on the seabed. One day the cable broke, and the model began drifting away. Huston knew it couldn’t be replaced at this late stage and, grabbing a bottle of scotch, climbed on to the giant prop, shouting, ‘Lose this whale and you lose me!’

As the crew looked on in astonishment, McClory and one of the assistant directors jumped into the water and repeatedly dived under to secure the line. All the time, giant waves were hurling the whale out of the water and slamming it down again. ‘These men were risking their lives,’ Huston later said. ‘But they finally got the line secured and the whale was under tow again.’7

Next, McClory came into the orbit of movie entrepreneur and producer Mike Todd and he was appointed director of foreign locations on the epic Around the World in 80 Days (1956). Forming a small unit, McClory spent five months location-hopping 44,000 miles across the globe.

While shooting in Paris outside the Ritz Hotel, the police kindly blocked off the road from traffic, but several cars remained parked on the road, looking incongruous in what was supposed to be a period picture. No problem – McClory towed them away. Unfortunately, one of the cars belonged to the French Minister of Justice and McClory and his unit were kicked out of the city.

Sneaking back in, McClory shot Phileas Fogg’s balloon going past Notre-Dame. Just as the police arrived in two Black Marias, sirens wailing, McClory rushed out of the back door of the cathedral with the can of film and jumped in a car waiting to take him straight to the airport.

In Bangkok, a simple scene of a boat sailing down a river was ruined because of a busy rail track in the background. Local officials refused to help, so McClory got his assistant to hurl himself in front of an oncoming tram to stop it long enough to get the shot. The poor man was arrested for attempting suicide and McClory had to bail him out of jail. After the shoot, McClory joined Todd in Hollywood and helped in post-production, earning an associate producer credit.

One of McClory’s closest friends during the 1950s and 1960s was Jeremy Vaughan, who also knew Fleming well, as his neighbour in Jamaica. ‘Kevin was a smooth operator, an attractive character, but not a particularly pleasant one, certainly compared to his brother Desmond, who was one of the kindest people you could ever meet. If a friend were in trouble, Desmond would always be there. Kevin would just tell you to piss off, if you weren’t any good to him. He’s been very cruel to a number of people over the years who thought they were his friends. The overdriving thing with Kevin was that he just wanted to be a celebrity, he wanted to be famous. He probably had some semi-professional technical interest in making a film, but he really wanted the glamour. He wanted to be amongst the people that he thought he should be amongst.’8

McClory was a keen practical joker. He even formed a club of like-minded pranksters and jesters that included Errol Flynn and Trevor Howard. Early one morning in Hollywood, as a big nightclub was turning out, McClory drove up in an open-top car wearing a horror mask borrowed from a studio. All the departing partygoers shrieked with fright and ran back inside. This was typical of McClory’s adolescent sense of humour.

He also got a detective pal of his in New York to arrest people as a joke. Sylvan Whittingham Mason, the daughter of Jack Whittingham, recalls another of McClory’s regular japes: ‘He would see someone he knew in a restaurant and, on the basis that you don’t normally look at who is serving you, would borrow a uniform and pretend to be the waiter at their table and spill things everywhere till they looked at him and realised who it was.’9

Jeremy Vaughan recalls one prank particularly well: ‘In 1961 I owned a horse that won the Grand National and sometime after that Kevin and I hatched this plot. He and his wife, Bobo, were going to give a birthday party to John Schlesinger, not the film director, but a South African who was a multi-zillionaire. And the gift to Schlesinger from all three of us was what we thought was the one thing a super-rich man would never have, and that was a gold casket full of horse shit.’10

The best of the lot was at the expense of Peter Carter-Ruck, McClory’s lawyer in the Thunderball court case. Ruck visited McClory in the Bahamas, bringing with him some important documents, and was picked up by his client at the airport. What Ruck didn’t know was that McClory was driving an amphibious car and, without warning, he violently swung the steering wheel, and they careered off the road and into the sea. Splashing its way across the harbour, the car duly arrived at Paradise Island. ‘It was a little wet,’ Ruck later wrote, ‘with waves coming over the windscreen, forcing me to protect the contracts from the water.’11

Following the successful release of Around the World in 80 Days, McClory took a holiday to the Bahamas, his first visit there. He fell in love with the islands immediately, and walking along a beach one morning, a thought gripped him: ‘My God, if you took a wide screen camera underwater it would be fantastic.’12

The immense clarity and colours of the Bahamian waters bedazzled him. No one had made a major underwater-based picture since Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) and the Jane Russell drama Underwater! (1955), and movie equipment was advancing all the time. Not least, wide-screen techniques, which had been introduced in a bid to attract audiences away from television and back into cinemas. McClory’s friend Mike Todd had pioneered his own wide-screen process, Todd-AO, which had been used on Oklahoma! (1955) and his own Around the World in 80 Days.

Seized by the commercial and entertainment value of an underwater adventure movie made in the Todd-AO process, in December 1957 McClory contacted John Steinbeck, the author of The Grapes of Wrath. He proposed a collaboration on a script about treasure hunters in the modern-day Bahamas. Steinbeck had worked in Hollywood but his interest in films, as he described in a letter to McClory in December 1957, had ‘diminished to the vanishing point because of the lack of creative originality among picture makers’.13

But Steinbeck was strongly drawn to McClory’s idea and, after several meetings with the Irishman, his enthusiasm increased. ‘Such a film,’ he wrote, ‘would be a work of art as well as being financially attractive, which is another way of saying that one hell of a lot of people would pay to see it.’14 Though a short treatment was written, the project faded away.

Back in the States, McClory bumped into an exuberant Mike Todd following the box-office success of Around the World in 80 Days. Todd invited McClory to come and work for him again, but the Irishman was keen to strike out on his own and explained his plan to make the ultimate underwater picture. Todd liked the idea. McClory then began to talk about another script that he felt had a lot of appeal and human interest. It was based on a short story by American writer Leon Ware about a boy who runs away from home to live on the San Francisco bridge. McClory wanted to switch the location to London and use Tower Bridge and a Cockney child. Todd listened, unconvinced, and urged McClory to make the underwater film. Puzzled, McClory asked why. ‘Well, I know you Kevin and if you make this bridge film you’ll go to festivals and win a lot of awards. But remember, you can’t eat awards.’15

Ignoring Todd’s advice, McClory went ahead with his script for The Boy and the Bridge, and it was his search for backers that led him to Ivar Bryce. The pair first met in January 1958 when McClory was out in the Bahamas working on his treasure hunter film. Bryce revealed an interest in the movie business and requested that, should McClory have any suitable projects, to get in touch with him in New York.

Bryce certainly had money to spare, with homes in Vermont, New York, London and Nassau. Best of all was Moyns Park, a country mansion in Essex with several hundred acres of park and woodland, where Bryce and his wife Josephine indulged in their passion for breeding horses and entertaining friends in suitably ostentatious fashion. Josephine Hartford was Bryce’s third wife, the granddaughter of George Huntington Hartford, founder of the large American A&P supermarket chain.

That April, during a trip to New York, McClory contacted Bryce regarding The Boy and the Bridge. Bryce liked the idea, liked McClory’s fun-loving enthusiasm even more, and agreed to back it. Together, they formed a business partnership called Xanadu Productions, named after Bryce’s beach house in Nassau. In the terms of a contract dated 6 May 1958, Bryce agreed to provide the necessary finance and McClory agreed to act as the film’s producer/director and assume the day-to-day management duties of the business, being paid a salary and expenses. He was also authorised to withdraw monies from the partnership bank accounts. Any net profits would be equally divided between them.

The day after signing the agreement, McClory sailed to England and rented a small London town house at 7 Belgrave Place, converting the downstairs rooms into an office for Xanadu and living in a two-bedroom apartment upstairs. Here, he revelled in a luxurious bachelor’s lifestyle that included his own manservant and a sports car. In Hollywood, he had owned a Cadillac.

Pre-production on The Boy and the Bridge began. In collaboration with his brother Desmond and Geoffrey Orme, a prolific screenwriter whose work included several of the popular Old Mother Riley films of the 1940s starring Arthur Lucan, McClory completed a script. Meanwhile, he had begun to hire key crew personnel. Notable among these was Leigh Aman, whom McClory first met on The African Queen. Aman had a long pedigree in British film, working first for Alexander Korda on films such as The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933), then for Ealing Studios and latterly John Huston. Aman had been a major in the Royal Marines during the war and took a leading part in the D-Day landings. His skill and experience as a production supervisor was to lend crucial support to the fledgling McClory, who had never made a picture of his own before.

The Boy and the Bridge began shooting in August 1958 and proved to be an experience that was both creatively stimulating and personally rewarding for McClory and Bryce, despite a strain on their relationship when the picture went over budget. The high-society connections of the two men allowed things to run smoother than they might otherwise have done. The government stepped in to allow the use of Tower Bridge for extensive location shooting and Princess Margaret attended the film’s premiere in Mayfair.

Buoyed by the potential success of The Boy and the Bridge, after seeing a rough cut, Bryce suggested to McClory they continue their movie-making partnership. ‘There are so many pictures screaming to be made,’ he said, in a letter to the Irishman dated 7 December 1958.

During a reading spree, McClory came across one fascinating true story, which no doubt appealed to his adventurous spirit, that of Dr John Williamson, who in 1943 discovered a vast diamond mine in Tanzania. Bryce, meanwhile, was toying with adapting Paul Gallico’s new novel, Flowers for Mrs Harris, a story he found particularly touching and appealing. It concerned a London charlady who wins the football pools and travels to Paris to achieve her dream of buying a Christian Dior dress.

Another of Bryce’s ideas related to the true-life story of one of the FBI’s most notorious criminals. Captured and held in a special detention fortress, he bragged about how childishly insecure it was and proved it by escaping. After his rearrest, the boss of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, made a deal with the criminal that if he designed an escape-proof establishment in New York he could choose whichever prison he wanted to spend his life sentence in. The criminal agreed and produced a blueprint for a building that the FBI built and maintained for years. When asked which prison the criminal wanted to stay at, he replied, ‘Alcatraz’. But why, seeing how Alcatraz was the toughest prison in the country? The man answered, ‘But all my friends are there.’

One gets the feeling from Bryce’s 7 December letter that he was immensely enjoying the buzz of being a part of the film world. Enmeshed as he was in the high-finance world of tax experts, lawyers and bankers, Bryce couldn’t help but find that all ‘Terribly dull in comparison to our enterprise, which will have an impact on countless inhabitants of this mortal world’.

His mind now full of ‘grandiose ideas’ and dreaming of ‘future peaks to climb’, Bryce had clearly decided that The Boy and the Bridge, far from being a one-off production, should be the launchpad for a whole slew of films from Xanadu, under the aegis of himself and McClory. For Bryce, the success of their debut feature represented ‘Fame for you, a warm reflected glow for me, some lovely real money to jingle in our pockets and throw carelessly back into further and grander exploits’.

Among those grander exploits Bryce had in mind was a James Bond film. ‘Have you read any of the Bond books?’ Bryce asked McClory one day.

The Irishman shook his head.

‘Then why don’t you read them and tell me what you think.’16

In January 1959, McClory purchased copies of the first four Bond novels: Casino Royale, Live and Let Die, Moonraker and Diamonds Are Forever. He didn’t just read these books; he analysed and digested them. ‘I enjoyed them but didn’t think they were particularly visual. That each and every one of them would have to be rewritten for the screen – written in a visual sense.’17

McClory also believed that much of Fleming’s work was ‘steeped in sadism’,18 which, if transferred to the screen, would be unpalatable to a mainstream audience. However, in James Bond 007, McClory knew that Fleming had conceived the most exciting character that, if put into a cinematic formula in the right way and using strong box-office ingredients, could be highly successful. ‘He leapt out of every page he was in,’ said McClory. ‘And clearly could be a great fantasy figure for film audiences of all sexes and ages.’19

It wasn’t long before McClory was craving a meeting with Fleming, and Bryce dutifully obliged. Fleming obviously responded positively to the encounter, despite McClory’s criticism of his work, because he sent the Irishman some specimen material, including a new Bond short story called Risico, later published with other stories in 1959’s For Your Eyes Only. In the covering letter, dated 29 April 1959, Fleming argued, ‘I would have thought that either Diamonds Are Forever or Live and Let Die would make good films.’ Alluding to McClory’s contention that his books required rewriting for the cinema, Fleming confessed, ‘The trouble about writing something specially for a film is that I haven’t got a single idea in my head, whereas if you were to decide on one of my books, such as Diamonds Are Forever, I could probably embellish it with extra gimmickry.’

On 7 May, McClory and Bryce met Fleming at Claridge’s Hotel and declared Xanadu’s intention to produce the first James Bond film. Fleming agreed to this but asked McClory to send him an official letter on the company’s headed paper confirming their interest. A few days later, McClory was suddenly struck down by a duodenal ulcer, which he blamed on the intense amount of work involved on The Boy and the Bridge. From his hospital bed, McClory wrote to Fleming on 11 May, confirming, ‘Xanadu Productions have decided that we would like to go ahead with our plans to make a full-length motion picture feature based on the character created by you, James Bond. We are at present exploring the wonderful and secretive world of Bond, and hope to be able in the very near future to make a choice of the novel we should like to film.’

Where producers and studios had failed to recognise the potential of 007, it had taken a relatively inexperienced filmmaker to see what should have been staring more seasoned professionals in the face. But what no one could possibly have realised at the time was that bitter seeds had been sown for forty years of lawsuits, court cases, injunctions, betrayals, deaths and broken lives.

2

THE FIRST JAMES BOND MOVIE PLOT

Flattered that someone in the movie business was finally taking a serious interest in his character, Fleming wrote to McClory the day after receiving his offer, on the 12th, ‘After seeing your work on The Boy and the Bridge there is no one who I would prefer to produce James Bond for the screen. I think you will have fun doing it and a great success.’ Just about to leave for Venice, Fleming stated his hope that by his return to London, ‘You and Ivar will have made up your minds on your choice of a James Bond story’.

However, McClory’s approach to Bond was to be radical. He was now convinced that the only way to proceed was to ditch the idea of filming an existing novel and instead create a totally new Bond scenario, out of which would emerge an original screenplay geared entirely to the requirements of a modern film audience. What is more, the Bond character would fit perfectly into his own desire to make an underwater picture in the opulent setting of the Bahamas.

In the late 1950s, the Bahamas was an unreachable paradise for most people: a world of millionaires, private yachts, splendid houses and beautiful women, a playboy’s haven ideal for someone like Bond. McClory positively bristled with the creative possibilities of merging these two elements together: Bond and the Bahamas – it simply couldn’t miss.

Once this was agreed, the search was on for a suitable story. McClory was later to claim that he was responsible for throwing into the mix the notion of an atom bomb and, influenced by a film about Al Capone that had just been released starring Rod Steiger, the Mafia would be a useful ingredient, too.

It was at this moment that an American lawyer and writer called Ernest Cuneo joined the team. A former legal adviser to Franklin D. Roosevelt, both a respected and cultivated man, Cuneo had known Fleming since the war when the author was with British Naval Intelligence and Cuneo worked for General William Donovan, the head of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services), the forerunner of the CIA. They first met in 1941 in New York, at the office of William Stephenson, the man called ‘Intrepid’ and a famed spymaster. Cuneo was to become Fleming’s closest American friend.

After the war, Fleming saw Cuneo whenever he was in the States. During one trip in 1954, the pair took off by train to Chicago. Cuneo always liked to describe how the train was already pulling into Albany before Fleming had finished instructing the steward how to mix the perfect martini. In Chicago, Fleming wanted to visit the location of the St Valentine’s Day Massacre and annoyed Cuneo by calling it America’s greatest shrine.

The two men travelled on to Los Angeles, where Fleming insisted on paying a visit to the LAPD, and then to Las Vegas, visiting each of the famous casinos and betting $1 on a game of blackjack. Fleming used much of the material from this cross-country trip in his novel Diamonds Are Forever. He even gave a character in the book, a Las Vegas cab driver, the name Ernest Cuneo.

Cuneo was also Ivar Bryce’s American solicitor and represented his interests regarding The Boy and the Bridge. Now, he flew into London to bring his highly charged legal brain to bear upon Bond. Buoyed by the news that The Boy and the Bridge had been selected as Britain’s sole representative at the Venice Film Festival (‘A thousand congratulations,’ Fleming wrote to McClory upon hearing the news. ‘This is a feather in your cap as tall as the Eiffel Tower!’1), a meeting took place at Bryce’s home of Moyns Park. In attendance were Fleming, McClory, Cuneo and Bryce. Here, ideas bounced around regarding a possible scenario for the Bond project, something to tie in with McClory’s concept of an underwater adventure. This was a notion that appealed to Fleming, being a keen scuba diver himself.

During the meeting, Cuneo carefully jotted down a rough plot based on the group’s discussion. After returning to Washington, he sent a memo to Bryce dated 28 May 1959. This was, in turn, handed to McClory, who later claimed that Bryce told him, ‘I do not know whether it is any good but have a look at it. It seems to use most of your ideas and so we might like it.’2 McClory then sent a copy to Fleming.

Given that Cuneo’s memo stands today as the first story outline for a James Bond movie, it was sent with a cautious covering note: ‘Enclosed was written at night, mere improvisation hence far from author’s pride, possible author’s mortification. Haven’t even re-read it.’

Clearly, Cuneo took inspiration from the Mike Todd film that McClory had recently worked on. ‘Assume that part of the essential formula for Around the World in 80 Days was a fast-moving plot, suspense, variety of scene, excellent photography and big-name stars in bit parts.’ As Cuneo understood it, the film would have to qualify under the Eady Plan. Set up in 1950, the Eady Plan was a British Government-sponsored protectionist subsidy for home-produced films. If the Bond picture qualified under the rules, a significant portion of its costs would be underwritten. Cuneo observed that, to qualify, the cast and crew had to be at least 75 per cent British.

The story was also required to take place largely in the Bahamas, where Xanadu productions hoped to establish a permanent home. As early as February 1959, McClory and Bryce broached the idea of setting up a studio in the Bahamas and making more films on the island. The ambitious plan was to convert an old aircraft hangar at Oakes Field, located in the island’s capital Nassau, into two sound stages and employ some 100 British, American and local technicians. McClory took Bryce to the prospective site on at least one occasion, walking over the roof of the hangar and showing him how it could be soundproofed to meet their purpose.

Setting up base in the Bahamas made sound commercial sense. As part of the British Commonwealth, it was within Eady subsidy boundaries, and as a Bahamian corporation, any profits the Bond picture earned in America would not be US taxable. Astutely, Cuneo suggested that shares could be sold in the upcoming film, ‘assuring Xanadu Bahamas promoters a profit before it started shooting’.

Cuneo set down, ‘Now, combining all of the latter, following is a basic plot, capable of great flexibility, but containing all elements, as outlined, financial and artistic. Offhand, a myriad of similar plots could be generated, but the following is illustrative.’

In Cuneo’s story, an enemy agent has infiltrated the USO, an organisation where performers travel the world giving morale-boosting shows to Allied forces. His intention is to detonate an atomic bomb on an American military base. Bond and his CIA buddy, Felix Leiter, are assigned to the case. Going undercover as an entertainer, Bond seeks the theatrical advice of Noël Coward and Laurence Olivier (in cameo roles, one presumes) to work out a suitable routine for him.

Bond identifies the spy and follows him to the Bahamas. There, Bond discovers that an Eastern Bloc power has a fleet of trawlers in the area, equipped with an underwater hatch for the secret transfer of atomic bombs via submarine. Before the bombs can be planted, Bond leads a team of scuba commandos on a daring underwater raid on the baddies. At the same time, above the waves, a large concert is taking place on the island featuring the likes of Frank Sinatra. Bond, naturally, emerges victorious. (For a longer version of this script, see Appendix 1.)

Cuneo included in his outline the hope that the US Government would be willing to co-operate by allowing them to film at certain US installations, perhaps even aboard their new aircraft carrier, Independence. He also suggested that the plot could be engineered to take place throughout the British Commonwealth – everywhere from Hong Kong to Gibraltar – to comply with the Eady Plan. As for star cameos, Cuneo reasoned that many entertainers holidayed or worked in Miami and could be flown over to Nassau ‘for half an hour, cost very low. Keven knows how 47 stars were bought into 80 Days for peanuts.’

The response to Cuneo’s story outline was swift and positive. Fleming called it ‘first class’, with ‘just the right degree of fantasy’ and ‘a wonderful basis to work on’. He was right. The stepping stones had been laid for Bond’s historic move to screen stardom.

3

ENTER SPECTRE

Despite Fleming’s glowing appreciation of Cuneo’s work, the writer saw problems with it, too, like the lack of a heroine for his hero to dally romantically with. Cuneo had suggested one of the female entertainers could turn out to be CIA. ‘Love interest easy to insert,’ he wrote offhandedly.

In a fascinating memorandum dated 15 June, Fleming proposed a new character: a beautiful double agent under M’s orders who assists the enemy. Her name – Fatima Blush. It is from Fatima that Bond learns details of the spy plot. In the underwater finale, Fatima would be on the enemy’s team and, Fleming wrote, ‘Her appearance in tight-fitting black rubber suiting will make the audiences swoon’. As the battle progresses, the spy discovers Fatima is a double agent and, while attempting to sabotage her aqualung, he is killed by Bond. ‘The curtain goes down as Bond and Fatima kiss through their snorkels,’ Fleming envisaged, adding, ‘My imagination has slightly run riot over this last scene but you see the point.’

Perhaps too much. At the subsequent trial, McClory stated that he thought Fleming’s idea of hero and heroine kissing through their snorkels ‘infantile’.1 Indeed, when the passage was read out in court there were bursts of laughter.

After this memo, neither the character nor the name Fatima Blush reappeared in any of the subsequent treatments or screenplays relating to Thunderball, nor in the novel or the 1965 film. Fleming, too, never reused it. But it was too good a name to ignore, and it was resurrected for the black widow SPECTRE assassin played by Barbara Carrera in the rogue Bond picture Never Say Never Again.

In his memo, Fleming turned next to Cuneo’s proposed use of guest stars: ‘I am all for the light relief of the actors, but this should be kept very separate from the main espionage plot, which must be kept serious and entirely credible.’ Fleming was adamant that, if the film was to work, its use of atomic bombs needed to be expertly researched and presented accurately. ‘This story needs to be solidly tethered to the earth with technical and factual background or we shall be dangerously on the verge of farce.’

By far Fleming’s biggest criticism was the use of communists as the principal villains: ‘It might be very unwise to point directly at Russia as the enemy. Since the film will take about two years to produce, and peace might conceivably break out in the meantime, this should be avoided.’ So, what to put in their place?

Fleming’s suggestion turned out to be the most significant contribution to the entire Thunderball storyline, and one of the most important regarding the future of James Bond – the creation of super-villains SPECTRE. An international terrorist group that is run with all the corporate efficiency of Microsoft or Shell, SPECTRE became Bond’s recurring foe in the early films and in subsequent novels. As laid out in Fleming’s memo, SPECTRE was ‘an immensely powerful, privately owned organisation manned by ex-members of Smersh, the Gestapo, the Mafia and the Black Tong of Peking’. Its ruse, Fleming suggested, was ‘placing these bombs in NATO bases with the objective of then blackmailing the Western powers for $100 million or else’.

Their headquarters, Fleming reasoned, might be ‘some large and well-guarded chateau in Normandy and we must be given a real idea of the hidden powers of both SPECTRE and the Secret Service’. To this end, Fleming confirmed that he had received full Foreign Office clearance for depicting the British Secret Service, ‘as I have done in my books and nothing in the Cuneo story would appear to be a breach of security’.

Like all great ideas, more than one person has claimed responsibility for coming up with SPECTRE. McClory later argued that using some form of international terror group was his suggestion. The Bond books, he felt, were too obsessed with the ‘red menace’ and it would work better if the enemy agents were not aligned to any specific government or political doctrine, but rather a private force. Strangely, the Irishman’s court statement only reveals that it was his idea to replace the Russians with the Mafia. No mention is made of SPECTRE. Significantly, various journalists covering the trial reported that it was agreed in court that SPECTRE was an invention of Mr Fleming.

As for the origin of the word itself, as any well-read Fleming fan will know, the author had used variations of it before. In the novel Diamonds Are Forever, the villain’s hideaway is called Spectreville, while in From Russia with Love, the decoder Bond steals is called a Spektor, changed obviously to Lektor in the film version.

Upon receiving Fleming’s comments on the Cuneo outline, McClory’s first inclination was to screw it up and throw it in the bin, fearing that if the author’s suggestions were followed, ‘We were very much in danger of creating another far-fetched plot steeped in sex and sadism which might be excellent for a novel but would not be suitable for transfer visually to the screen by Xanadu’.2 McClory now firmly believed that Fleming’s earlier confession about not having a single idea in his head when it came to writing specifically for movies was correct as far as a James Bond screenplay was concerned.

4

THE DEAL IS DONE

Much was beginning to happen in the world of James Bond. As Fleming described it to Bryce in a letter dated 2 July, ‘Conflicting bids for and interests in part or whole of the James Bond sausage have been coming thick and fast’. American television executive Hubbell Robinson had made a firm bid of $10,000 for a ninety-minute TV version of From Russia with Love, and wanted an option on a television series with a maximum of forty-four episodes – ‘for a fat fee’, stated Fleming. Another American producer was offering a similar proposal, plus movie rights. And there was an offer of £20,000 and 15 per cent of the profits on a British television series. In ‘desperation’, Fleming appointed MCA as his agents for all film, television and dramatic rights to the Bond books. Put in personal charge was the respected Laurence Evans, who also represented Alec Guinness and Ingrid Bergman. ‘So I’m in good company,’ boasted Fleming.

Fleming accepted the bid from Hubbell Robinson but stalled on everything else in deference to the Xanadu proposal. However, in the same letter of 2 July, Fleming urged Bryce to hurry up and make a definite offer or he would accept the other bids. ‘Xanadu will of course get a most favoured treatment if and when they express a firm interest.’

Fleming, influenced by MCA, was obviously out to get the best possible deal and made the point that any company, ‘friend or foe’, who acquired the copyright to make Bond films had to make a down payment. If the planned From Russia with Love TV special and Xanadu’s Bond film succeeded, all past and future Bond material would acquire a greatly enhanced value. ‘And I am urged by MCA not to mortgage the future, except at a worthwhile price.’ Fleming then tempered his greed by saying, ‘I fear I must think of all these considerations since James Bond is my entire stock in trade and I have not got the energy to create a new character.’

Fleming was happy to act as creative consultant on the film, even write a draft script, providing he be paid a fee, as any writer would, along with a percentage of the gross profits. ‘I think that you should be clear in your mind how far you really want to go with this James Bond project and what terms Xanadu is prepared to lay on the line.’ Then it would only be a question of putting the proposal to MCA, ‘And I shall naturally press them to accept any reasonable offer. But I cannot afford to put the whole James Bond copyright in escrow in exchange for shares in a non-existent company.’ Xanadu was in the process of being re-formed in Nassau, with a hoped-for capital of $3 million from various potential backers.

Then came the crunch. ‘My own recommendation is that you have made one successful film, perhaps too expensively. You should now make a second successful film watching the costs a bit more carefully. This film should be a James Bond film and thus be likely of success under Kevin’s brilliant direction.’ Fleming had been impressed with The Boy and the Bridge when he saw it at a private screening at Shepperton Studios and wrote to McClory saying that, in his opinion, it was a ‘small masterpiece’ for which the Irishman was ‘solely responsible’.1

Put simply, Fleming was offering Xanadu first refusal on the character of James Bond for movie exploitation. ‘And in him you have potentially a very valuable property if you can sign him up for several years.’ McClory was only too aware of this. Why else were he and Bryce so eager to secure not just any old rights to make a Bond film, but the rights to make the first Bond film? And having acquired these rights, there was no reason, suggested Fleming, why the Bond character could not then be sub-leased, first to Hubbell Robinson’s TV From Russia with Love, then back to Xanadu for the feature film or later to a television series. Another interesting Fleming proposal was that the same thing could apply, in lesser degree, to various subsidiary characters, such as M and Felix Leiter.

One gets the impression, reading this letter, that Fleming was desperate for Bryce to buy into Bond, to have someone he knew and respected own the film copyright to his character rather than some faceless company or Hollywood producer. The concluding paragraph strikes a particularly friendly note: an apology for sending Bryce so much food for thought. ‘But the whole thing is getting a bit too big for me and, before MCA finally devours me, I thought I ought to give you a last clear think.’ He then added a PS, ‘If anything isn’t clear to you in this letter, it isn’t clear to me.’

Fleming’s letter did the trick and within days Bryce got in touch to make a firm offer – Xanadu wanted to go ahead with the Bond film. As payment Bryce agreed to send Fleming a cheque for $50,000, which the author would use to take shares of equivalent nominal value in Xanadu. ‘I am really overjoyed that everything is now settled in this splendid and expeditious fashion.’