Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

The invention of the aeroplane was the dawn of a new way of travelling. Its potential was quickly realised, and aircraft were developed to carry first mail and then passengers, over distances that would have previously taken many hours or even days. Successive aircraft changed how we experience flight and how far we could go, introducing new standards of on-board service. Flying became an experience like no other; modern airliners offer unparalleled levels of comfort and economic benefits for their operators with levels of automation hitherto unimagined. 50 Airliners that Changed Flying presents the exciting airliners which can genuinely claim to have changed air travel, from the early mail planes and piston liners through the emergence of the jet age, to the sleek and ultra-modern airliners of today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 114

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Matt Falcus 2018

The right of Matt Falcus to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-7509-8876-6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in India

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

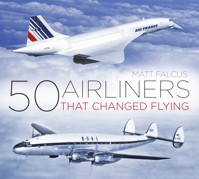

Cover Illustrations

Upper Front: Despite its technological advances, only two airlines ever ordered Concorde aircraft. (Author’s Collection)

Lower Front: The fuselage of the Constellation has a distinctive shape, with a bulbous forward fuselage that tapers to a point at the tail, and three vertical fins spread across a wide horizontal stabiliser. (Author’s Collection)

Back Left: Passengers enjoy the comfortable spacious interior of the Stratoliner.

Back Right: The Benoist Type XIV was probably the first aircraft to fly a scheduled passenger service.

Page 2: Sud Aviation Caravelle cockpit. (Author)

Page 4: As well as comfortable passenger cabins, the DC-3 was used as a troop transport during the Second World War. (Author)

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Introduction

1 THE EARLY YEARS

Wright Flyer

Benoist Type XIV

Sikorsky Ilya Muromets

Handley Page Type W

Junkers F13

Fokker F.VII

Ford Tri-Motor

Dornier Do X

Junkers Ju 52

Boeing 247

Douglas DC-2

Douglas DC-3/C-47

Short S.23 Empire

2 POST-WAR AIRLINERS

Beech 18

Boeing 307 Stratoliner

Lockheed Constellation/Super Constellation

Boeing 377 Stratocruiser

de Havilland Canada DHC-2 Beaver

Antonov An-2

Vickers Viscount

de Havilland DH.106 Comet

Boeing 707

Tupolev Tu-104

Sud Aviation Caravelle

Fokker F27

Grumman Gulfstream I

Douglas DC-8

Vickers VC10

3 JUMBOS, MASS TRAVEL AND UTILITY AIRCRAFT

Hawker Siddeley HS.121 Trident

Ilyushin Il-62

Boeing 727

British Aircraft Corporation One-Eleven

de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter

Boeing 737

Douglas DC-9/McDonnell Douglas MD-80

Britten Norman BN-2 Islander

Tupolev Tu-144

Embraer 110 Bandeirante

Tupolev Tu-154

Aerospatiale/BAC Concorde

Boeing 747

McDonnell Douglas DC-10

Airbus A300

British Aerospace 146

Boeing 767

Cessna 208 Caravan

Airbus A320

Boeing 777

Airbus A380

Boeing 787 Dreamliner

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank a few individuals for their help and support in producing this book. Jon Proctor, whose experience working in the airline industry and collection of images from those days is beyond compare. I’d like to thank my wife, Lucy, for her support in my aviation interests, and my parents for encouraging me to follow this interest from an early age. Finally, I’d like to thank Amy Rigg and all at The History Press for bringing this book to life.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Matt Falcus is a British aviation writer and author of a number of books. His interests in aviation started at a young age when watching aircraft from the viewing terraces at his local airport. In 2003, he began writing articles for consumer magazines such as Airliner World and Aviation News, and has written popular guides for enthusiasts both online and in print. He has also been interviewed on BBC Radio 4, Radio 5 Live, and collaborated with organisations such as British Airways, London City Airport and the Royal Air Force. Matt is also a private pilot.

INTRODUCTION

Sitting on board an Airbus A380, among more than 500 other passengers, it’s difficult to imagine that little over 100 years ago flight was a new, experimental endeavour. Early pioneers saw its potential in delivering the mail much quicker, and the onset of war meant great advancements in aeroplanes because of their ability to be used for military purposes. Yet flying one or two passengers was a novelty in those early days.

It took a number of years before the commercial possibilities of flying passengers and making money doing so dawned on aircraft manufacturers. The early limitations of aircraft, in terms of how far they could fly and how many passengers they could carry, certainly restricted their impact to small, expensive endeavours by a few entrepreneurial pioneers.

The first few decades of flight were an experimental time, with aircraft built in small numbers and their reliability being something of an issue. Yet by the 1930s great strides were being made to produce machines capable of comfort, range, speed and reliability that could be mass produced and prove suitable for the needs of air carriers all over the world. It did not take long before it became possible to link greater distances, across oceans and continents, with greater numbers on board.

With flying remaining the reserve of the rich, aircraft were developed with on-board luxuries reminiscent of the hotels and clubs one might visit, and heavily inspired by sea and train travel. Early airliners included wicker chairs in elegant saloons, with washrooms and impeccably dressed waiters. As aircraft grew in size, passengers would still regularly dress up to take a flight even into the 1960s.

Yet with the economics needed to make air travel pay, the advancement in aircraft turned in the direction of size and reducing costs. Aircraft and their engines became efficient at transporting large numbers of people over great distances, at speed, whilst reducing the cost of operating. In doing so, air travel was brought to the masses. Many might argue that, in today’s world of low-cost carriers and routes linking thousands of city pairs, it is more akin to taking a bus than a luxury train or ocean liner.

A busy scene of early piston airliners at New York La Guardia during the post-war boom in air travel, made possible by pioneering aircraft designers and manufacturers, and the airlines that saw the opportunity. (Jon Proctor Collection)

However, along the way many great leaps have taken place. Those early piston aircraft with open cockpits very quickly gave way to luxury airliners with sleeping berths, pressurised cabins and engines capable of flying at greater speed. These in turn gave way to the jet age, flying higher and further in comfort. Aircraft such as Concorde enabled travel at immense speed, while the Boeing 747 ‘jumbo jet’ became the so-called ‘queen of the skies’. Finally, today’s ultra-efficient airliners are built of composite materials that give strength at a fraction of the weight, and offer complex technology and computerised systems.

Great superpowers of aircraft manufacturing were established early on and were responsible for many great leaps and advances in design and technology. In the early days Britain, France and Russia were years ahead. Yet America proved that aircraft could be made commercially viable and produced in great numbers, creating important companies such as Boeing, Douglas and Lockheed. Europe’s response has been the collaborative Airbus, whilst aircraft manufacturing in post-Soviet Russia has always remained strong.

The aircraft in this book have all played a major role in developing air travel in some important or pioneering way. Many are household names and have enjoyed a long-lasting impact on the way we travel; others have long been consigned to the history books and now can only be enjoyed in museums, yet must be remembered for their innovative contributions. Others are still flying thousands of passengers every day all around the world. Either way, these airliners will forever be responsible for shaping how we fly.

The luxurious cabin of an early Imperial Airways aircraft. (Author’s collection)

WRIGHT FLYER

On 17 December 1903, the world was changed forever when two pioneering brothers took to the skies for the first time in a heavier-than-air craft from a blustery beach, in front of a crowd of onlookers. Everything we know today about flight and aircraft would come from that moment, including its development for military and commercial purposes.

On that day, Wilbur and Orville Wright assembled their Wright Flyer aircraft, having aborted an earlier attempt a few days prior, on the beach at Kill Devil Hills, near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Using a rail as a runway, the pair tossed coins to decide who would make the first flight, so confident were they that their aircraft would indeed break the confines of gravity.

Launching into the wind, the first flight left the rail and travelled a distance of 120ft, with Wilbur at the controls. The distance was less than the wingspan of a modern large airliner, yet it was enough to propel the brothers into history.

The distance flown by the Wright Flyer was less than the wingspan of an Airbus A380. The only way a pilot could control the aircraft’s direction was by lying on his stomach, facing forward, and manipulating levers with his hips to control the surfaces of the wings and tail plane.

Where it all began. The Wright Brothers and their Wright Flyer in North Carolina in December 1903.

Little is written about the aircraft itself, or what else happened that day. The Wright Flyer was influenced by the work the Wright brothers had carried out previously with gliders. It was a biplane built of spruce, with an engine designed specifically for the job to power two propellers.

For the remainder of that ground-breaking day the brothers took turns flying a further three times, each over a greater distance, until a heavy landing followed by a gust of wind damaged the aircraft; it would never fly again.

The Wright Flyer could by no means be described as an airliner, however it certainly changed flying and led to the development of passenger-carrying aircraft as we know them today. The design was not without flaws, and the most important thing to understand is that the results of testing this aircraft helped determine what would or would not work on future aircraft.

The Wright Flyer was stored in a barn for many years before its historical significance led to it being displayed in exhibitions around the world. On 17 December 1948, the forty-fifth anniversary of its only flights, it was put on display in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, moving to its National Air and Space Gallery in 1976. It was fully restored in 1995.

BENOIST TYPE XIV

Those familiar with the appearance of the large, sleek airliners that whisk passengers around the world at speed today might be forgiven for thinking this small flying boat was nothing more than an early experiment in flight. However, it was the aircraft that proved air travel could be profitable, albeit in a very short timescale.

Thomas Benoist was an automobile mogul, having made a fortune from the early years of cars. Following the invention of the heavier-than-air aeroplane by the Wright Brothers in 1903, Benoist had become firm in the belief that air travel would be the next great leap from the automobile and set about designing and building his own aircraft.

Alongside business partner Paul E. Frasler, the entrepreneur built the Benoist Type XIV in 1913 to operate for Frasler’s new St Petersburg–Tampa Airboat Line in Florida. Widely regarded as the world’s first scheduled airline, the first flight was on 1 January 1914. The new aircraft had the perfect opportunity to bridge the 18 miles between St Petersburg and Tampa that otherwise had to be navigated by lengthy road, rail or boat journeys.

The Benoist Type XIV itself was not remarkable in many ways, featuring a standard design of the time and operating from water. However, it could operate with a single passenger alongside the captain at a ticket price of $5 each way. The airline was able to pay its contract fees easily and make a profit, proving the viability of air travel on routes where it could offer such an advantage over ground or sea routes.

The route didn’t last long due to political tensions; however, Benoist was spurred to build larger aircraft to cope with demand and opportunities were soon being realised around the country and the rest of the world to make air travel a commercial enterprise. The airline was born.

The Benoist Type XIV was likely the first aircraft to fly a scheduled passenger service.

SIKORSKY ILYA MUROMETS

Not long after the invention of the aeroplane, its potential was realised around the world. Igor Sikorsky was a prolific aircraft designer in Russia who had been responsible for a succession of experimental fixed-wing aeroplanes, leading to his monstrous (at the time) Ruskii Vitiaz four-engine biplane, nicknamed ‘Le Grande’.

Based on this design, Sikorsky went on to develop the Ilya Muromets class of aircraft, named after the Slavic folk hero. The principle behind the aircraft was to carry passengers and enter commercial service, serving the communities scattered throughout the Russian Empire, with luxuries built in that had rarely been seen before on board an aircraft, including a washroom and a spacious saloon for up to sixteen passengers.

The Ilya Muromets used four Argus AS I 100hp engines.

The initial S-22 model caused quite a stir and became the talk of Russia when it first flew in 1914. It had four Argus AS I engines delivering 100hp each, and would break all height records at the time by flying at 6,500ft (2,000m) above ground with a full payload of passengers. The range of the aircraft was 370 miles (600km).

The timing of the development of the Ilya Muromets coincided with the outbreak of the First World War. Despite its potential as a commercial airliner, the needs of the Russian military for a bomb-carrying aircraft far outweighed this, and all future development of the type shifted focus. It would be unrivalled in this new role and significantly help the war effort.