16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

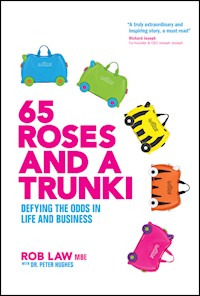

***BUSINESS BOOK AWARDS - FINALIST 2021*** An inspirational success story that shows how anyone can be a champion, overcome challenges and create a better world for yourself and others 65 Roses and a Trunki: Defying the Odds in Life and Business, is the extraordinary success story of entrepreneur Rob Law, designer and inventor of Trunki, the award-winning children's ride-on suitcase that's sold millions of units worldwide. Born with cystic fibrosis, Rob watched his twin sister die from the same illness at sixteen. Told he could not expect to live into his twenties, he made a promise that he was going to defy the odds and live a long and successful life. Despite being humiliated in Dragons Den where his business was described as "worthless", Rob went on to create a new category of consumer product, build a global business brand, become an accomplished athlete, get an MBE from the Queen, bring joy to millions of children all over the world and become a father to three children after being told he would die childless. After beating overwhelming odds on the road to success in his personal and professional life, Rob wrote this memoir to help anyone facing difficult challenges in life and business. From brand-building and harnessing your creativity to managing a chronic health condition and facing your demons, you'll learn how to defy the odds, follow your passion, keep fighting when experts are telling you to quit and overcome every challenge you face. 65 Roses and a Trunki is a life-affirming book. Drawing on key insights from personal and business psychology, it tells an inspirational story that can be your story too.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 324

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

65 Roses

A Promise

Astronauts and Spaceships

Horizons and Habits

Hospital and Hustling

Dragons and Strap Hooks

Self and Others

Guilt and Forgiveness

Pregnancy and Productivity

Cash and Copies

Courts and Losses

Toys and Toddlers

A Ride on a Trunki

AUTHOR'S NOTES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PICTURE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INDEX

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

i

ii

v

vi

vii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

213

214

215

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

‘Rob provides all entrepreneurs with an inspirational example of courage and determination – his life story is compulsive and compulsory reading.’

Sir John Timpson CBE, Chairman, Timpson

‘Rob Law's life is an inspirational lesson in humility and resilience.’

Richard Reed CBE, Co-Founder Innocent Drinks

‘A poignant memoir filled with physical bravery, entrepreneurial focus and a designers determination.’

Andrew Lynch, Associate Business Editor, The Sunday Times

‘A stunningly honest and personal book from a man who has looked inside himself to make sense of the world, of business and what drives us to achieve. It speaks directly to purpose and how vital that is in business and life.’

Paul Lindley OBE, Founder, Ella's Kitchen

‘Rob Law is an inspiration to us all. Read this book and you will understand why and how he's built a globally successful business and how he strives to ensure that each day counts. We can all learn something from reading these powerful pages; lessons to apply in our business, and in our life.’

Emma Jones MBE, Founder, Enterprise Nation

‘Rob doesn't have the words “no” and “can't” in his dictionary. In this powerful, moving book, he shares his incredible personal story with lessons for us all about resilience and self-belief. For anyone who's got a dream, this is essential reading – but I warn you now, your excuses for not taking action will ring hollow.’

Nadine Dereza, Journalist, Presenter & Media Director

‘Rob's account of his life with CF is heart-warming and deeply moving. His grit and tenacity are an inspiration.’

David Ramsden, Chief Executive Cystic Fibrosis Trust

“A truly extraordinary and inspiring story, a must read for all aspiring entrepreneurs. Rob shows how persistence, belief and hard work are the “must have” tools required to build a successful business and brand”

Richard Joseph, Co founder & CEO Joseph Joseph

“A wonderful book…Rob's frankness talking about cystic fibrosis and what he's doing to make lives better is inspiring”

Will King, founder, King of Shaves

“An inspirational story of resilience, hardship and humanity. I was hooked from page 1 and could not put it down. Truly anything in this world is possible.”

Tom Pellereau, Inventor and Winner BBC Apprentice.

“Rob is at heart a designer, one who brings empathy, curiosity, courage and a deep optimism to overcome every hurdle and aspire to make the world better. A life affirming book for all.”

Clive Grinyer, Head of Service Design, Royal College of Art

“At a time when the world is changing through a global pandemic, 65 Roses and a Trunki seems even more poignant to how we live, who we are and what we value. Rob Law’s inspiring and powerfully moving story grabs you from the very first page. It’s a powerful, honest and heartfelt story of survival against the odds. This is a book that everyone should read.”

Professor Steven West CBE DL, Vice-Chancellor President and CEO, University of the West of England

65 ROSES AND A TRUNKI

DEFYING THE ODDS IN LIFE AND BUSINESS

ROB LAW MBE

WITH DR. PETER HUGHES

This edition first published 2020

© 2020 Rob Law.

Registered office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Law, Rob, 1977- author.

Title: 65 roses and a Trunki : defying the odds in life and business / Rob Law

Other titles: Sixty five roses and a Trunki

Description: Chichester, West Sussex, United Kingdom : John Wiley & Sons, 2020. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020000665 (print) | LCCN 2020000666 (ebook) | ISBN 9781119628590 (hardback) | ISBN 9781119628637 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781119628613 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Law, Rob, 1977- | Businessmen-—Great Britain—-Biography. | Luggage industry—Great Britain. | New business enterprises—Great Britain. | Success in business-—Great Britain.

Classification: LCC HC252.5.L39 A3 2020 (print) | LCC HC252.5.L39 (ebook) | DDC 338.7/68551092 [B]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020000665

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020000666

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover Design and Images: Rob Law & Phil Dobinson

For Kate, your bravery still inspires me today

65 Roses

In 1965, Mary Weiss volunteered to work for the Cystic Fibrosis Trust after learning that her three children suffered from the disease. Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a chronic illness that affects the respiratory, digestive and reproductive systems. It clogs the lungs with thick, sticky mucus and impairs the functioning of the pancreas. The result is a life of relentless physiotherapy, nebulisers, antibiotics and hospital admissions of varying severity. While treatments are improving and evolving, it kills most sufferers in their youth or in their prime.

When Richard was diagnosed, Mary Weiss moved the family from Montreal to Palm Beach in Florida on the advice of her doctor, who had told Mary that her children would be likely to die before they were 10 years old and the sea air would give them a better quality of life in what little time they had left.

One day, Mary's four-year-old son Richard said to her:

– I know who you’re working for.

Mary was horrified. At the time, Richard confessed his knowledge of his mother's work, her eldest child, Arthur, was seven and the youngest, Anthony, was 16 months old, so she had not told any of them they suffered from cystic fibrosis or that they would be likely to die young. Her relentless phone calls aimed at raising money for the Trust were often done from home and now, confronted by her son, she feared the worst. He must have heard her use the words ‘cystic fibrosis’ many times and perhaps he had learned what it was and that he had it.

– What am I working for, sweetheart? she asked, nervously.

– You're working for 65 roses.

Mary burst into tears when she realised that when she said cystic fibrosis, her son heard 65 roses.

Time treated the family harshly. Arthur, the eldest child, died young and Richard also lost his battle with cystic fibrosis, while Mary continued to battle for a cure until her death at the age of 77 in April 2016.

One of Mary's many legacies is that children who suffer from CF still refer to the illness as 65 roses. As a sufferer myself, I'm touched by this story of how an ugly genetic illness came to be associated with the scented beauty of roses.

This ambiguity defines for me the delicate balance between life and death, success and failure. As with all such stories, luck plays a pivotal role. To get CF, both parents have to be carriers of the relevant genetic mutations, which means the odds of the disease being passed to me were 25%. As an entrepreneur, the odds of me creating a global brand and becoming a millionaire were vanishingly small. Yet, when the dice rolled, I got the illness and the global brand.

Would I prefer the dice to have behaved as the odds predicted, making my health good and my bank balance empty? I never ask myself questions like that. We get the life we are given and all we can do is make the most of it, and that is what makes writing this book such a difficult task. Is it a book about battling terminal illness? Or is it a book about a product I designed while at university that changed the way children travel? Or is it perhaps about what it takes to start with nothing, be ridiculed by experts and go on to prove everyone wrong?

In fact, it is a book about all these things. Regardless of whether we are born with a genetic disorder that is likely to kill us in our youth, we will all, at some point in our lives, have to fight illness and misfortune. If we start our own businesses, we will all have to fight for the cash to keep our dreams alive. Most businesses will perform modestly and many will go bust. The rich and successful entrepreneur is the exception that proves the rule.

In sickness and in health, through success and failure, the course our lives take is often random and unpredictable, but how we deal with the randomness is not. That small slither of opportunity where we can manage the unpredictability that envelops us on all sides is what we can control. Fighting for your life or making your first million requires the same skills of courage, emotional discipline and a capacity to deal with unfairness and adversity without becoming a victim of either. This book is about those skills, what they are and how you can learn them. They are tools for life and I will do my best to teach them by telling my story about what it means to defy the odds in life and business.

A Promise

Lives turn on small details.

Mine turned on a knock on a door.

A tall, thin man with a scruffy beard came into the classroom. I didn't know he was coming for me, so I carried on with my work.

I heard whispers. I looked up and saw him talking to the teacher. They glanced across at me as they spoke. There was something in their gaze. I didn't like it. It's the way people look when something breaks the familiar patterns of the world and turning away isn't an option.

The tall, thin man with the scruffy beard walked towards my desk.

Whatever he'd brought into the classroom, it was for me.

There were five boys and one girl in our group. We'd just begun our A levels and this was the first day of An Introduction to Engineering, a three-day course at Loughborough University. The problem we'd been given to solve was how to design a retractable platform to allow people to get closer to the wing of an airplane during production.

This was the kind of problem I liked. It had a solution. It wasn't messy.

The tall, thin man touched my shoulder.

I froze.

– Rob, he whispered, you'd better come with me.

I followed him out into the corridor. I knew what was coming. I brushed my shoulder with my hand, as if to wipe the knowledge away. It stuck. I tried again.

– It's your father. He's on the phone and he needs to talk to you.

We went into his office.

– Dad? I said.

– Rob …

He paused.

I knew.

Please don't talk to me. Let me go back in.

– … It's Kate … he said, his voice frail.

Please, please, don't let it be.

– … she's not going to make it, Rob, and you'd better come to Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Small details, like a knock on a door, change lives.

Of course, I should have seen it coming.

Like me, my twin sister had been born with cystic fibrosis. Twenty months before the knock on the door she'd had a heart and lung transplant. She'd either been doing well or, as most of us do when faced with our deepest fears, we chose to see hope. On the anniversary of her transplant the local paper ran a feature headlined: ‘Brilliant new life for Kate aged 15’.

Along the top of the page ran another sentence in bold: ‘Celebrations one year on after breath of fresh air’.

The article continued in the same vein with the paper quoting Mum saying that Kate ‘is living a completely normal life and the beauty of the new lungs is that they won't clog up because they are not genetically hers. It was an awful life when I look back and a year later it was impossible to tell she ever lived in the shadow of death’.

A few months before the ‘shadow’ returned, we went to Canada for a family holiday to celebrate Kate's new future. When she got back, her body began rejecting the donated organs. Every day she got worse. She spent Christmas in Great Ormond Street. I still have the picture of her lying, asleep, on her bed, wearing a thin blue hospital gown. Behind the bed is a teddy and a balloon and cards and Kate just lying there, eyes closed, drifting away.

A man, dressed as Father Christmas, stands next to her, holding an unopened present. He's staring at the camera, an uncertain look on his face, struggling to understand how his gifts can change anything. Only a few weeks earlier, we were on holiday. Playing Gameboy. Laughing. Squabbling. We saw the Rockies and stayed in Vancouver and Edmonton. We travelled through dense forests and, if I close my eyes, I can still smell the fresh, earthy scent of pine trees that takes me back to a time when the future felt safe. I, like our family in Canada, felt blessed that Kate was doing well. She wasn't well, of course, but feelings are insistent. They pester you until they're believed and maintaining a semblance of normality is enough for us to bury what we know. We keep feeling and hoping until our emotional illusions are shattered and we're left, stranded, staring at nothing, like detectives hunting a criminal only to find every house empty. We're a sluggish species, always playing ‘catch-up’ with our own lives and all it takes is a knock on a door to remind us, to wake us from our slumber, to hurl us, screaming, into a world we've buried.

Kate was dying and, despite the facade of denial, I knew it. When what we fear is too real to bear, we turn away. When the knock on the door came, I convinced myself it was just a knock, like thousands of other knocks I'd heard before. Even when I heard my father's voice, breaking as he spoke, I thought everything would be alright. It had to be because it wasn't just about Kate. It was about me. I suffered from the same illness and her destiny was also mine.

Mr Blackford drove me to London in a minibus. Just the two of us. He sat in the front. I sat behind. It was dusk when we left and the January sky loomed dull and grey. We drove in silence. I was numb. Facing Kate's death meant facing my own future and I was more comfortable building things, like retractable platforms, than I was imagining my body breaking apart. So, I built a wall. An imaginary one as solid as any wall that's ever been built and I stuck my illness behind it. If any of the bricks fell away, even if there was a crack in the mortar, then what broke through might be stronger than me, so I kept this ‘other life’ hidden, a secret I kept from myself.

As we travelled down the motorway, I took refuge in the reassuring hum of the engine. The silence trapped me and Mr Blackford in separate worlds. It kept the wall intact.

It was late when we arrived at Great Ormond Street.

Too late.

Kate was dead.

My Dad told me she died two hours before we arrived. They'd turned her life support off. They had no choice. Whatever they did, she was going to die quickly. An act of love, turning the machine off protected her from senseless suffering.

Mum cried uncontrollably. I hated seeing her heart break. There's worse off than you, she said to us when we grew tired of taking our medicine or when the shadow of our illness was too dark. Now, staring at Kate, my mother slipped into a dark hole, my father more helpless than I'd ever seen him before, my brother only eight years old, his world no longer safe, and me, numb, not knowing what to do or say.

The supports of my life were falling away and all I could do was stare at my sister, lifeless, her eyes closed. I have no idea how long I stood in the room, tracing the lines of the tubes that stretched from her body to the machines around her bed. I kept expecting her to move. Smile like she used to. Do something to annoy me. Anything. Everything inside me froze and I knew if there was a thaw in my heart, I'd lie next to Kate and die with her.

At some point, I must have left the room where Kate lay because someone asked me, my mother I think, if I wanted to stay or go back and finish the course at Loughborough.

I chose to go.

Nobody asked me why or if I was sure I wanted to leave.

If they'd asked me, I wouldn't have had an answer to give. I'd lived my life as if it was normal, as if cystic fibrosis was nothing more than an inconvenience and now I was facing the truth.

I hated the illness. It was alive, as close to me as death and as distant as a star. Me and not me. Mine and not mine. My only defence was to refuse to let it consume me.

We drove back in the same minibus, the silence brutal and comforting. This time, the numbness was more complete. Push a needle through my hand, I thought, and I'll feel nothing. I can't afford to.

When we got back to the university, it was the middle of a starless night.

I felt alone, my twin sister dead, killed by the illness we shared.

I remembered the knock on the door. A quiet, apologetic knock that tore my life in two. Such misery often comes from events that force their way into our lives with the fury of sudden storms. Yet these storms mature slowly in our sightline. It's the lag before they strike that gives us the comfort of denial. So we look away until our lives are shattered. It's a familiar pattern. This is mine:

I was told my life would be shorter than most.

Despite the relentless routine of drug taking and therapy, most days I felt well enough to deny this knowledge.

The more I carried on as normal, the more I convinced myself I wasn't ill.

Then my twin sister got sick and had a heart and lung transplant and I convinced myself she'd make a full recovery.

Then came a knock on the door.

Followed by a vigil at Great Ormond Street Hospital where I arrived too late to make a difference.

The journey back to a university and the resumption of an engineering course, gave me the space to embrace the necessary illusion of normality.

If you think this pattern is strange, it isn't. We all do it because we must, the only difference being that you probably have the luxury of a more plausible denial than me and denial is built in just the same way as retractable platforms or children's ride-on suitcases. It begins with a compulsion to create and is sustained by a process of trial and error that never ends. It doesn't matter that nothing is ever completed to the point of perfection, not lives, not products, not businesses, nothing. The key is that you have to persist and it's this very act of persistence that creates an illusion of progress. It routinises our lives and, where there is routine, there is belief that storms will pass us by.

I remember a quote from Ernest Hemingway:

‘How did you go bankrupt?’ Bill asked.

‘Two ways’, Mike said, ‘Gradually and then suddenly.’

That's how it happens. We persist in our routines, every day making the world more familiar, more solid, less likely to break. In business, we come to the same office, speak to the same people, nurture the same clients, analyse the same projections, and all the while the ground is shifting under our feet.

… Gradually

Then one day, we notice that this gradual shifting has taken a turn for the worse: the ground isn't there anymore and we're falling, fast.

… and then suddenly

People who die, like businesses that fail, don't want it to happen. We fight to keep breathing like we fight to keep cash in the bank and balance sheets solvent. Stopping breathing or going bust are demons we deny. We're good at denial because we're hopeless optimists, continually misreading the world, making it more benign, tamer, than it is. The pay-off is that we sleep at night, imagining tomorrow or, at worst, the day after tomorrow, will be better than today. The downside is we don't see the danger until it's too late. Later, when we look back at the devastation, we wonder how it was we missed the signs.

… Kate had cystic fibrosis.

… A heart and lung transplant at 15.

… What did I expect the outcome would be?

The answer is I expected her to live and hope was the last thing I lost.

In Greek mythology, Pandora, the first woman, is created by Zeus to punish the human race for the theft of fire from the gods. She's given a jar and when it's opened all the evils that inflict us are released into the world. When the evils escape, human life is full of suffering. However, one evil remains in the jar: elpis, the Greek word for hope or expectation. When I first heard the story I never understood why hope was an evil. I do now. For anyone who has seen a loved one die of cystic fibrosis or cancer or any long illness where emotions swing from hope to despair in weeks, days or even hours, living in constant expectation of recovery against all odds is both what keeps us fighting and breaks us when the battle is lost. Perhaps this ambiguity is why elpis stayed in Pandora's jar: hope, despite its capacity to wound, also sustains us in our darkest moments. I didn't know it at the time of Kate's death, but the degree of serenity in our lives is in direct proportion to the lowering of our expectations: if we expect immunity from suffering, we will live lives of quiet, corrosive desperation. If we expect nothing, we are likely to live a happier life, because we are less at the mercy of events outside our control.

After Kate died, I decided that most things that happen to us are unbearably random and it was easier to immerse myself in my passion for design and creativity than it was to expect anything to work itself out for the better. When I'm designing, creating, planning, I'm absorbed in the moment, without a past or a future, a pure present, free from suffering. So that's where I've lived the best parts of my life, the place where everything I've ever designed is created and where I go when I'm fearful of the illness that stalks my life.

I must have slept a few hours before going back to the classroom at Loughborough University.

At first, my classmates were that awful mixture of pity and fear, shuffling their feet, talking to me in whispers and broken sentences. I didn't want to talk about Kate. I wanted everything to be normal. They must have sensed that because, after these awful moments without any emotional geography, they got on with the day. And so did I.

I spoke to my parents in the evening. They asked how I was.

– I'm okay, I said, and the course is good.

They talked about arranging the funeral.

– I don't know when it will be yet, Mum said.

– Okay, I said.

I didn't say anything else. To myself or to them.

By the third and final day of the course, life felt normal again. I let habit and routine take me to a place where I could get on with living, a sanctuary like the emotion that kept the poet Matthew Arnold from breaking under the pressure of a lost love: ‘we forget,’ he wrote, ‘because we must’. That's why, on the second night after my return, I went to the pub with my classmates. I don't remember much, only the name, the Frog and Firkin, the rattle of shoes on wooden floors and foam on my lips, the residue of waves I'd sunk with my beer. My forgetting was, of course, brittle. I knew I could never forget the twin sister I loved or the image of her, lifeless, in a hospital bed. But I knew I had to do my best to move on with my life or be crushed by the loss. The illusion held for as long as I was away from home. Physical separation can bring emotional distance in its wake and, when I returned to school, Kate's friends stood in the drizzle to greet me. The illusion shattered and I wept uncontrollably, unable to recover myself until I was alone.

Between death and burial there's a hiatus, a gap in the rhythm of a life that's finished and not finished at the same time. I can't remember much of what I did during that time. I remember feeling numb and, when that feeling thawed, overcome with rage at the unfairness of everything. What had Kate done to deserve this? She was kind and brave and funny and smart. And now she was dead.

Yet, my mother's grief was, if anything, more unbearable.

In this hiatus, people came to visit. Dozens of them. Every time a new face arrived at the door, the wound in Mum's heart deepened. I watched her repeat the same grief over and over again and I grew to dread a knock on the door and hate the people who came to give their condolences. They meant well and, when a person dies, especially one as young as Kate with her whole life ahead of her, it opens buried grief we all carry for the losses we've suffered and the losses we know are to come. It's often only through the suffering of others that we truly feel our own pain.

Despite this, I hated the impact on Mum. She, more than anyone, didn't deserve this. She'd taught us to feel blessed we were alive. She made sense of our suffering and now all I could see was her pain, haemorrhaging in the direction of every visitor that came. She greeted them with what strength she had left. When the door closed behind them, she sank, exhausted and overwhelmed.

I wanted a deal with God: turn the clock back, I said, make all this pain not happen and I'll …

That's where I got stuck. There was nothing I could give, real or imagined, big enough to cut this deal. Paralysed by guilt at being the first born, the one who survived, I had nothing to give except my life.

Minutes, hours, days passed and the funeral got closer. Mum and Dad busied themselves with the practicalities of the funeral. It gave them a purpose, a way of loving Kate that anchored her presence, however fleetingly, in the proximity of the world.

We drove the short distance from our small hamlet to Tarvin Church, where the funeral was held. A dark, grey January day. I don't think it rained. I bore the coffin with my uncles. I remember the hollow crunch of my shoes on the gravel, music I can't name and faces pressing against me.

After the service, we buried Kate in a far corner of the graveyard. The long, slow walk from the church door to the grave felt like it would never end. It did, of course, and afterwards, Mum wrote a letter to friends and family. In the fourth paragraph she wrote, ‘In August, we had the best family holiday we could have had’ and, as if to prove how quickly things change and how unprepared we are, the fifth paragraph begins:

During this holiday Kate showed signs of not being quite right … On our return, September and October were spent trying to find out why she was less than 100% … All the tests carried out could find nothing wrong … After still no signs of a reason, from the multitude of tests carried out, her breathing started to deteriorate …

That's how tragedy unfolds, a slow, unfathomable descent into our deepest fears. Mum's response to this is typical: ‘It is,’ she wrote, ‘so hard to understand why’.

The question of meaning or purpose, the ‘why’ question, is the hardest one to answer. In the years immediately after the Second World War, the Jewish psychiatrist Viktor Frankl was interned in Theresienstadt in 1942 before being moved to Auschwitz and finally to a labour camp. Only he and his sister, Stella, survived. Determined to make sense of his suffering and the wasted lives of his family, Frankl wrote Man's Search for Meaning, in which he wrote that ‘those who have a “why” to live for, can bear with almost any “how”’.

More than 60 years after the publication of Frankl's book, the author Simon Sinek returned to the same themes in his groundbreaking business book, Start with Why, in which he wrote: ‘very few people or companies can clearly articulate why they do what they do. By why, I mean your purpose, cause or belief – why does your company exist? Why do you get out of bed every morning? And why should anyone care?’ He concludes that people ‘don't buy what you do; they buy why you do it’.

If meaning or purpose, ‘why’ is the primary driver in life and business, then everything else we chase, like wealth or success or happiness, is just an effect of our ability to ground our lives and our businesses in a strong sense of purpose. ‘Success, like happiness’, wrote Frankl, ‘cannot be pursued, it must ensue’.

In the weeks after Kate's funeral, I found it hard to find any meaning in her death. I withdrew into myself and, if there was any purpose in my life at that time, it was for Mum to stop hurting. I had more empathy for her than I did for myself. I often struggle to feel compassion for myself. Only when I'm in hospital for treatment or when the cystic fibrosis impairs the routine of my life, do I even get close to feeling for myself the love I feel for my parents, my family and for Kate.

So I went as often as I could to Kate's grave. Sometimes I spoke to her. Other times I stood in silence, not sure what to say or feel. As teenagers Kate and I were very different people. She loved books, while my dyslexia made it difficult for me to read. She excelled at school until her health declined, while I was put into the special needs class. What bound us was the illness we shared.

At junior school, we were kept together to take our medicine and to make sure we didn't eat fat. We looked with envy at other children playing outside while our daily routine was driven by managing our illness. This routine didn't just affect our school lives. It began first thing in the morning when Mum made sure we did our physiotherapy to keep our airways clear. This involved breathing in different patterns and moving the body into various positions, mostly with head tipped lower than the body. Once in this position, I'd tap on my chest like a drum to create a percussive effect which drained secretions and ventilated my lungs. We also took our drugs and nebulisers before we went to school and the routine repeated after school with more physiotherapy, nebulisers, and ended last thing at night with more drugs before bed. Dad once drilled a hole in the living room wall through which a small plastic tube passed, which meant we could nebulise our drugs without Mum, Dad, and David, my younger brother, inhaling the fumes.

Despite the many ways in which cystic fibrosis distanced me from my friends, I craved normality. Some days I didn't do my physiotherapy and went running with my father. As a teenager I began weightlifting to build body mass, which enabled me to store the energy I'd need if I fell ill. I took up cycling. It gave me freedom and allowed me to visit friends in nearby villages. At 13, I started a paper round. Driven by an unarticulated drive to defy my illness and live a normal life, I created my own routines and found meaning in turning my illness from a dark, unmanageable shadow that hung over my life to a practical problem to be solved.

After Kate's death, Mum became committed to a kind and gentle Christian faith and threw herself into raising funds to find a cure for the illness that killed her daughter and that would, one day, kill me. That was never going to be my path to meaning. I had no religious or philosophical answers to the question of why Kate died or why I and many others live with incurable illnesses or find ourselves victims of circumstances beyond our control. Of course, it's all unfair but moaning about unfairness when you can do nothing to change what you're moaning about is a certain path to misery.

What, then could I do?

I couldn't let my life get stuck in visits to Kate's grave or in grief. I hated watching Mum collapse under the weight of grief then pull herself up only to repeat the cycle again. If there was a meaning in this suffering, I found it in an act of defiance. I had no control over the fact that Kate died. I had no control over the fact that I, too, might die from the same illness. But I did have control over what I did with my life. Whether I chose to be crushed under the weight of what I was carrying or whether I chose to live my life well.

I chose to live.

I made a promise to myself. I promised that Mum would never grieve over me. Kate was the last child she would lose. Determined to defy my prognosis, I took control over my life in the best way I knew, which was to solve the problems I was good at solving and forget about the ones over which I had no control. Those problems were practical ones and they were the key to my survival. From an early age, I loved making things, finding out how things worked, moulding fragments of the world to my will. I had a prodigious imagination and imagined making extraordinary things. I also had the self-discipline to make it real. I couldn't solve the problem of senseless suffering. To this day, I can't watch a hospital scene on television where a life support machine is being turned off, without crying. I also can't listen to my partner telling me her problems without wanting to find a practical solution. While that may be irritating for her at times, for me it's the cornerstone of my survival and my success.