Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

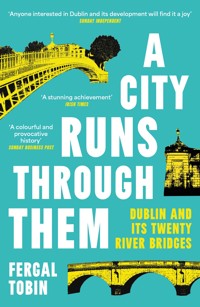

An original and fascinating history of Dublin that tells the story of the city through its bridges. Dublin started life on the south bank of the River Liffey and for six or seven centuries that is more or less where the town stayed. In all that time, there was only one bridge across the river. Then, suddenly, in the twenty years after 1670, three more bridges were thrown up and the north side was born. Within a century, Dublin was being talked of as one of the ten largest cities in the whole of Europe. Built over a span of a thousand years, the twenty bridges that now traverse the tidal section of the Liffey have each contributed to the city's development, as it pushed through the open fields north of the river and east towards the bay, so much so that it is possible to piece together Dublin's history by tracing their construction in chronological order. Starting with Church Street Bridge, Dublin's first, which dates back to the Vikings, and ending with Rosie Hackett Bridge, erected in 2014, Fergal Tobin charts the rise of Ireland's capital city as never before and reveals how, perhaps more than any other city in the world, it has been truly made by its bridges.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 382

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

By the same author

The Irish Difference

The Irish Revolution, 1912–15: An Illustrated History

The Best of Decades: Ireland in the 1960s

Published under the name Richard Killeen

Ireland: 1001 Things You Need to Know

A Pocket History of the Irish Revolution

Ireland in Brick and Stone

Historical Atlas of Dublin

A Short History of Dublin

A Brief History of Ireland

A Short History of the 1916 Rising

A Short History of the Irish Revolution, 1912 to 1927

The Concise History of Modern Ireland

A Timeline of Irish History

A Short History of Modern Ireland

A Short History of Scotland

The Easter Rising

A Short History of Ireland

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2024 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Fergal Tobin, 2023

The moral right of Fergal Tobin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978-1-83895-936-4

Design benstudios.co.uk

Map artwork by Jeff EdwardsEndpaper image: British Railways poster (London Midland Region), Dublin by Kerry Lee, 1954 (© Science Museum Group)

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

i.m. Nora Pigott (1914–2006)my mother

The business of Dublin is to show its face to England and its arse to Kildare.

Richard Killeen, attrib.

CONTENTS

Preface and Acknowledgements

A History of the City in 362 Words

Maps

Introduction

1. Fr Mathew Bridge

2. Islandbridge

3. Rory O’More Bridge

4. Grattan Bridge

5. O’Donovan Rossa Bridge

6. Mellowes Bridge

7. O’Connell Bridge

8. The Ha’penny Bridge

9. Heuston Bridge

10. Liffey Viaduct

11. Butt Bridge

12. Loopline Bridge

Water Break

13. Talbot Memorial Bridge

14. Frank Sherwin Bridge

15. East Link

16. Millennium Bridge

17. James Joyce Bridge

18. Seán O’Casey Bridge

19. Samuel Beckett Bridge

20. Rosie Hackett Bridge

Envoi

Notes

Bibliography

Illustrations

Index

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

UNLIKE MY PREVIOUS book, The Irish Difference, which started life as one thing and finished as another, this idea for a history of the Liffey bridges in the order of their construction has been nagging away in my head for years. Well, it’s done now for better or worse. I hope that the intention that lay behind the idea – that such a survey might prove to be a new and original way of tracing the development of Ireland’s capital city – has been realised.

A City Runs Through Them could not have been attempted, let alone written, without the work of a generation or more of outstanding scholars who have done so much to recover Dublin’s past. Their work is acknowledged both in the source references studded through the text and in the bibliography. In this connection, I must single out the late J.W. De Courcy’s The Liffey in Dublin as an exemplary work of scholarship. I know of no other work, on this subject or any other, so scrupulous, reliable and abundant.

I am of course grateful to those friends and colleagues who read and reviewed the text in draft and supplied helpful comments. They include Angela Long, Michael Fewer, Jonathan Williams, Sandra D’Arcy and Pat Cooke. It is hardly necessary to say that any and all remaining errors, omissions and other bêtises in the body of the text are their fault. I take the Nixon defence: I accept responsibility, but not the blame.

As before, I am grateful to the staff at Atlantic Books for the faith they have shown in the book. Will Atkinson as publisher and James Nightingale as senior editor have been vital supports as well as sure-footed professional advisers.

A HISTORY OF THE CITY IN 362 WORDS

DUBLIN BEGAN AS a Viking trading settlement in the middle of the tenth century. Location was key to its quick ascendancy among Irish towns. It commanded the shortest crossing to a major port in Britain. By the time the Normans arrived in the late twelfth century, this was crucial: Dublin maintained the best communications between the English crown and its new lordship in Ireland.

The city first developed on the rising ground south of the river where Christ Church now stands. The English established their principal citadel, Dublin Castle, in this area. Throughout the medieval and early modern periods, the town’s importance was largely ecclesiastical and strategic. It was neither a centre of learning nor fashion, and its commerce was modest.

The foundation of Trinity College in 1592 was a landmark event but the town did not begin to turn into a city until after the restoration of Charles II in 1660 and the arrival of the Duke of Ormond as his viceroy. The final victory of the Protestant colonial interest in Ireland ushered in the long peace of the eighteenth century. Then a series of fine, wide Georgian streets, squares and noble public buildings appeared, Dublin’s greatest boast. A semi-autonomous parliament of the Anglo-Irish creoles provided a focus for social life. The city prospered.

This parliament dissolved itself in 1800 under the terms of the Act of Union, and Ireland became a full part of the British metropolitan state, a situation not reversed until Irish independence in 1922 (Northern Ireland always excepted). The union years saw Dublin decline. Fine old town houses were gradually abandoned by the aristocracy – increasingly absent – and became hideous tenement warrens. The city missed out on the industrial revolution. Its commercial middle class migrated to new suburbs beyond the two canals.

Independence restored some of its natural function but there was still much poverty and shabbiness. The 1960s mini-boom was a false dawn. Only since the 1990s has there been real evidence of a city reinventing and revitalising itself. The 2008 economic crash was a form of cardiac arrest, leaving many unresolved problems. There is still much to be done.

A CITY RUNS THROUGH THEM

INTRODUCTION

THERE ARE MANY ways of telling a city’s history. Few things that have happened have happened entirely by accident or chance. Most are deliberate, and there is hardly a human action more deliberate than throwing a bridge across water. That is especially so in cities with well-articulated quarters on either bank, as in Paris or London or, on a more modest scale, Dublin. There are rivers in cities like Edinburgh or Brussels that you might miss completely, so tucked away are they. There are cities like Turin or Vienna where the substantial part of the city is on one bank only. There are places with no rivers at all.

Dublin started life on the south bank of the Liffey, on the rising ground that runs up to Christ Church. That rising ground is in fact a geological ridge that runs east–west parallel to the river and offers strategic control over its tidal reaches. And for six or seven centuries, that is more or less where the town stayed, with just a nervous north-side suburb in nearby St Michan’s parish: Oxmantown. Until the 1660s Dublin was at first little more than a village, then a town of some little consequence, but still small as such places go, in comparative terms, and still hugging the area around that ridge of rising ground that runs east from Kilmainham to what is now the west end of Dame Street.

In all that time, there was only one bridge over the urban Liffey. There was no need for more, there being so little on the far side. Then suddenly, in the space of fewer than twenty years after 1670, three more bridges were thrown up and the north side was born. (There were actually four, but one was soon destroyed in a flood and not rebuilt.) A process was begun that might be described as northing and easting. As the modern city formed, it did so by twin impulses: developing what had hitherto been open fields north of the river while simultaneously – albeit gradually but inexorably – pushing east towards the bay.

The purpose of this book is to trace the process by looking at these various river crossings chronologically, in the order of their construction. I begin this book as I shall finish it, deficient in knowledge of civil engineering. So how these bridges were actually constructed and made safe is less my subject than the municipal and political motivation behind these structures and the effect that each one had on its hinterland on either side of the river. From this patchwork quilt I hope to construct an impressionistic history of the city. It can be little more than that, for you will learn little here of the far-flung suburbs, remote from the river. What you may learn, however, is how the musculature of the city developed and how it determined the shape and purpose of the modern urban space.

Every Dubliner knows about north-side–south-side jokes: well, without the bridges there wouldn’t be any. The contrary theme of east and west may seem less obvious but is, in my view, more potent sociologically, as I hope the following pages demonstrate. Without that process of northing and easting, for instance, there would be no trace of that postal district and state of mind known as Dublin 4, the locus classicus of bourgeois amour propre – which would be an intolerable absence.

The book, therefore, does not follow the flow of the river from Islandbridge to the sea. Instead, it hops back and forth according to the construction dates of the bridges themselves. So this is jigsaw history: until all the awkward pieces have been properly placed, the overall picture remains unclear.

What is undeniable, though, is the extraordinary momentum that the bridges provided to the city’s sudden and precocious development. Prior to 1660, Dublin is an inconsequential little provincial town in an out-of-the-way location. Within a century, it is being talked of as one of the ten largest cities in Europe. Of course, much of that is speculation, as there was no certain way of counting people in a pre-censual age, although measuring urban footprint presented fewer difficulties. But population estimates can hardly have been so inaccurate or inflated as to be completely false. Who can say with certainty that Dublin was bigger or smaller than Naples or Madrid in 1780? But the mere fact that it was being discussed in the same breath as these great royal and imperial centres marked its advance from the margins of urban consciousness towards the centre. These estimates of comparative size, while never absolutely definitive, are generally accepted as roughly accurate by most modern scholars.

It might have happened otherwise. Who is to say? Dublin could have stayed on one side of the river, like Turin, and pushed south. But it didn’t. It went north, and in due time it swarmed all over the place. And without the bridges, none of that would have happened. Something else inscrutable might have quickened, and for all anyone knows, Terenure today might be regarded as the Boulevard Saint-Michel or the Upper East Side. But to the relief of many, that’s not how it all panned out.

Obviously, not all bridges are equal. While it is the purpose of this book to trace each one and its effect on the geographical and historical development of the city, some were obviously more critical to the Dublin that has actually evolved from the series of accidents, plans and contingencies that constitute any historical process.

The two bridges that I think have mattered most to the development of the modern city – the one we actually know in the twenty-first century – are Capel Street Bridge and O’Connell Bridge. Incidentally, for most of what follows in this book, I avoid as far as I can the ‘official’ names of bridges, which names have been subject to change over time. British ruling worthies, viceroys and their lady wives generally got bridges (and other items of public furniture) named for them. Unsurprisingly, that habit passed out of fashion at independence, and the bridges, like the mainline railway stations, were generally renamed for persons distinguished in the radical nationalist tradition. In one case, Rosie Hackett, the choice remains original and is a nod both to feminism and to the labour movement; in three others, literature is acknowledged in the persons of Joyce, Beckett and O’Casey. But in general the patriots scooped the pool.

Not that it was especially helpful in identifying which bridge was which. Most Dubliners would find it hard to tell you which one was Rory O’More Bridge – I could not have told you offhand before I began working on this book – and might prefer Watling Street Bridge, although even there many would remain a bit vague. Old-timers called it Bloody Bridge, the name that had the longest shelf life and the one that Joyce uses in Ulysses. But as we shall see, it was renamed for O’More.

Something similar, although not as stark, applies to one of the two most consequential bridges. Which one is Grattan Bridge? Some Dubs might struggle, or at least hesitate. And what was it originally? Ah yes, Essex Bridge – named for the viceroy whose patronage enabled it. Essex was his honorific; his family name was Capel, thus the name of the street that runs off it to the north. So calling it Capel Street Bridge, which most people do, makes everything clear, while official nomenclature, both anachronistic and modern, only causes degrees of confusion.

On the other hand, there is absolutely no confusion about which one is O’Connell Bridge (although in the old days it was Carlisle Bridge, named for yet another viceroy, as was the street that gave on to it from the north side, Sackville Street: what a well-mannered, deferential lot we were, never done tipping our caps to the quality). The bridge was not renamed for Daniel O’Connell until 1880 and the street not until as late as 1924. But even when they were Sackville Street and Carlisle Bridge, nobody was unsure of their location. Not so, as we have seen and will see later in some more detail, with the post-independence renamings.

Of all the twenty bridges covered in what follows, these two – at Capel Street and at the southern end of O’Connell Street – are the two that more than any others changed the entire orientation of the city.

It will be elaborated on in the book but it bears mentioning here in summary form. Prior to the building of Capel Street Bridge, the north side barely existed. Speed’s map of 1610 is our best guide in this. Across the river from the little town on the south side, huddling around Christ Church Cathedral, although by now well spread beyond the small embracing walls, there was only a scatter of habitation.

John Speed’s Dubline is the oldest surviving map of the city, published in 1611

The big thing that had been over there – St Mary’s Abbey, established as a Cistercian foundation around 1147, having previously been a Savignac house for a few years and possibly a Benedictine one as early as 9681 – had been razed in the state-sponsored vandalism known as the dissolution of the monasteries in the late 1530s. It was a substantial complex, whose sister house was Buildwas Abbey in Shropshire.

Yet that earlier dissolution of monastic and other religious establishments, with its incalculable artistic losses at the hands of fanatics, was a moment of caesura. Nothing much happened in urban development that can engage the historical memory for the next hundred years or so, but when things started to happen, they happened in a rush. This was in the 1670s and ’80s, when suddenly four new bridges were thrown across the urban river where hitherto there had only been one. Of these four, Capel Street Bridge was not the first – that distinction belongs to O’More/Bloody/Watling Street Bridge a bit upriver – none the less it was by far the most transformative.

As we shall see in chapter 4, the effect of building this bridge was to open up and urbanise the north shore of the river. It was filled in and developed in a remarkably short period of time, considering the inertia antecedent. It was not alone in this: as we’ll see in chapter 3, O’More Bridge was material in this respect as well, as were all the other bridges thrown up at this time. But none were as decisive in turning Dublin from a huddling little trading town on one side of the Liffey only to a proper two-sided city as we have come to know it. Look at Charles Brooking’s map of 1728 – not much more than a century after Speed’s – and you are hard pressed to believe you are looking at a rendering of the same place. The early north side is full.

Dublin’s north side developed exponentially in the century between Speed’s and Brooking’s maps

Moreover, the river is progressively contained. The original embanking went back to Dublin’s earliest days, but it was only with the sudden growth of the burgeoning town that the process became urgent and continuous, so that the North Wall – running all the way down to what is now the East Link Bridge – was in place as early as the first decades of the eighteenth century, although constantly in need of updating and repair until it reached its modern state around 1840. Look at any of the old maps of the town, say pre-Brooking, to see how ragged was the natural course of the Liffey, all little indents, pools and irregularities. The quay walls imposed a sort of Enlightenment order on this undisciplined state of nature. Before it was anything else, Dublin was a harbour town. Its life blood was marine commerce; therefore, that commerce, as it expanded, required engineering infrastructure even that far downriver, well away from the town, to sustain itself.

It is ironic that Dublin’s classical age – the Georgian period, to employ a shorthand that is almost accurate – should have been born on the north side and most of its early heroic architectural achievements located there, considering the sad shambles into which so much of it has been allowed to fall in modern times. That’s for a later plaint in the body of the book. But it makes the point that without the north side the Dublin that we actually know is literally unimaginable. Capel Street and O’Connell Street as undeveloped green fields, anyone?

The manner in which the story that follows is told tells us something about Dublin. This question of using the Liffey bridges as the prompt or the hinge on which the historical development of the city is hung is only possible for a small city, and one with not too many bridges. And Dublin, for all its occasional bouts of self-congratulation – which are fair enough: no one should be ashamed to cheer for their team – is a small city. It is a small city, but one with a very large footprint for its population. This low-density sprawl makes it difficult to facilitate an excellent, integrated and efficient public transport system.

You couldn’t write a book like this for London or Paris. London is just too vast; Paris has a ridiculous number of bridges. In London, it would not be difficult to write sensibly about Westminster Bridge and to identify its contribution to the history of the city. Likewise London Bridge, obviously, or Waterloo Bridge. But Chiswick Bridge or even Kew Bridge? By the time you’d got from Teddington – the tidal reach of the Thames – down to Tower Bridge, you’d have a baggy, incoherent book. As for Paris, don’t even think of it.

But it’s manageable for Dublin, even allowing that all twenty bridges are not equal in their historical significance and – to be fair – some are of minimal significance, if even that. I have tried to reflect these inequalities in the text. But in the cases of the bridges that have the greatest importance, their contribution to how the city actually developed has been crucial. Once more, the most obvious examples are Capel Street Bridge and O’Connell Bridge, for the reasons set out earlier in this introduction. There is, however, something to say about all of them.

So: time to cross that bridge now that we have come to it.

ONE

FR MATHEW BRIDGE

THE BRIDGE ON this site was, until 1670, the only urban river crossing on the Liffey. It lies just to the west of the Four Courts, upstream a little from the old walled Viking and early Norman town. It stands at or very close to Áth Cliath, the ford of the hurdles. This was a fording place across the river at low tide: the hurdles refer to what is supposed to be a series of timber mattings that gave pedestrians a degree of grip as they made their way across. This ford gave the town that grew up beside it its name in the Irish language: Baile Átha Cliath, or the town of the ford of hurdles.

It was not without occasional danger. The annals record a catastrophic event in 770 when an army, apparently returning from a victory and perhaps flushed with alcohol, was caught by a sudden incoming tide: many were drowned. This is a reminder that the entire stretch of the Liffey covered in this book is tidal, from Islandbridge at the western margin to the point where it empties into the bay below the East Link Bridge. And Dublin Bay is tidal, very. The tidal rhythm basically occupies about six hours each day, giving two high and two low tides in any twenty-four hours. On the day I type this, the difference in height between the first high and the first low tide is 2.15 metres or (in old money) 7.05 feet, a fairly typical tidal range, although it can on occasion go as high as 3 metres. So, eastward on the river estuary the tide is full and generous when flowing but leaves a rather desolate sandscape – with orphaned pools of water here and there – when fully out.

That desolate scenario is repeated upriver at low tide, so that even today, with the river firmly embanked at Fr Mathew Bridge, it is hard not to conclude that the troops who drowned in 770 were either reckless or unlucky, or perhaps both. Did they decide to take their chance against a fast-flowing tide? It’s hard to account otherwise for what actually happened, fuelled perhaps by drink and victors’ bravado. Of course, the river was not embanked in those days and flowed unimpeded in its natural channel, making it both wider and shallower at this point. At any rate, this incident, for which the annalistic evidence appears reliable, is a reminder that, hurdles or no hurdles, the fording point was not free of hazard.

But why was there a ford here at all? After all, there was no town nearby, not yet, nor would there be the beginnings of one for the best part of another two hundred years. And for six centuries and more after its modest foundation by the Vikings in the late tenth century, it was a place of little consequence in the great affairs of the world. So why was there a ford here?

Look seaward, then landward. This was obviously a site of some importance. All the later significance attached to Dublin derived from its marine approaches. Its bay is the only great, dramatic opening for shipping on the east coast of Ireland. The Boyne, just over forty kilometres north of the Liffey, has no such reception room. Although its valley for some distance inland has been settled since Neolithic times, the river enters the sea at Mornington in a manner that is best described as apologetic. Dublin Bay, on the other hand, is a fabulously extravagant marine drawing room that bids you in.

The ford was where it was not because of the sea or the river, but because of the roads to landward. This was the point at which four major roads from the Irish interior converged. Why here? There was no town, no settlement, nothing permanent. Intelligent inference is the best that can serve. These internal roads led towards Dublin Bay to facilitate commerce with Roman and later with Anglo-Saxon England, for which the bay provided a point of goods inwards and outwards. It opened the shortest sea route to the rich midlands and south of England for the trading of whatever there was to trade. In Roman times, the principal connection was with the fortified town of Deva Victrix, a Roman fort (castrum) from which it takes its modern name, Chester. A sufficient number of Roman artefacts have been discovered at Irish archaeological sites to render a Roman commercial presence in Ireland beyond dispute.

The ancient roads that converged on Dublin ran through flat country, giving easy access both ways. The one exception was the Slí Cualann, coming from South Leinster and the Waterford region. It encountered the natural barrier of the Wicklow Mountains, immediately south of the modern city. But even there, while it was difficult to go through the mountains, it was perfectly possible to go round them. There was a coastal littoral to the east which offered one option; moreover, to the west the mountains quickly fell away down to the plains of Kildare. All in all, the road system offered easy access from Dublin Bay to the interior, and it offered the interior easy access to Dublin Bay.

An archaeological illustrator’s impression of the hurdled ford

So, from ancient times, before we have any secure written records that mark the beginnings of history proper, there is sufficient circumstantial and archaeological evidence to suggest that the Dublin Bay area was some sort of a trading entrepôt. There is no evidence of any permanent settlement until the arrival of the Vikings in the late eighth century, but again it would not be wholly unreasonable to suppose that there may have been seasonal trading camps in the area from time to time.

So who laid the hurdles that formed Áth Cliath? The hurdles amounted to a matting of latticed timbers secured to the river bottom by some means or other. That suggests something more than a temporary gimcrack, which in its turn suggests some sort of regular – if not actually permanent – human presence. If the fording point was, on this speculation, a commercial pinch point, it was in the interest of those traders and merchants who functioned there to maintain it in a state of regular good order.

Nor was it all ford. The site chosen for the crossing also contained an island in the river. This was Usher’s Island, long since gone as a physical feature, but very handy in the long ago. It survives vestigially in the name of one of Dublin’s south quays, opposite where it once stood (see chapter 17). It would have made every sense to have taken advantage of such a fortuitous feature in selecting the site of the ford. So, in aggregate, a number of factors combined to make this the remote spot near which would later cluster the early permanent Viking settlements that were the physical beginnings of Dublin: the converging roads; the convenient ford; the ready access to the bay for commerce.

Its natural position combined with human activity marked it out as the site of the island’s principal town from the beginning. The many Irish marine raids on Roman Britain – one of which produced St Patrick – had been a consistent feature of the early centuries AD. Many must have launched from Dublin Bay. It is not easy to imagine where piracy stopped and trade began, that is supposing that they could be segregated at all and were not part of a common, tangled warlord system. We don’t know what was traded either way, although it is likely that Irish volunteers for the Roman army were a feature; that would have been consistent with ordinary Roman practice on other margins of the empire. We don’t know for certain if slaves were traded, as they were to be in Viking times to come, but it is a reasonable speculation. The entire ancient world depended on forced labour: slaves were an irreplaceable part of every ancient economy and society, without which none could have functioned. No slaves, no Aristotle.

The coming of Christianity to Ireland in the fifth century AD resulted in the development of many monastic sites. In fact, monastic organisation was to remain the defining feature of the Irish Christian Church for centuries. In this, it echoed other church organisational structures at the margins of early Christianity, where Roman influence had been weak or nonexistent: the Coptic Church of Upper Egypt and Ethiopia is a good example, as are the wilds of Arabia Deserta with its famous monastery of St Catherine.

However, and here’s a crucial difference, in the post-Roman heartland of Latin Christianity, roughly co-terminus with the nerve centre of Charlemagne’s empire astride the Rhine, ecclesiastical organisation was diocesan. Each diocese was based on a town; such towns were a necklace of commercial and military settlements of Roman origin that survived the collapse of the empire and then furnished the musculature of the diocesan system of church organisation.

Ireland, having no towns, had not the means to establish dioceses along continental lines, so the monasteries filled the gap. The first monastery along the Liffey of which we have solid knowledge dates from the seventh century and was situated downstream of Átha Cliath, at the eastern end of the long gravel ridge running in from Kilmainham, just before it falls away towards the top of what is now Dame Street. The site is now occupied by Dublin Castle. In the seventh century, it had the advantage of both height – thanks to the ridge – and the presence of water on three sides: the Liffey itself at the front and the Poddle – long since culverted – wrapping round to the south and east as it approached its confluence with the bigger river. In particular, the Poddle formed a tidal pool later named in Irish as Dubh Linn, the dark pool. This was anglicised in due course as Dublin and gave the city its name in the English language. The fact that Dubh Linn and Átha Cliath were different settlements, albeit contiguous, accounts for the linguistic difference in the Irish and the English names of the modern city. The Irish form of the earlier settlement stuck, as did the anglicised form of the latter.

Then the Vikings came.

The early Scandinavian settlement, on the rising ground that ran up from the river to the gravel ridge, was protected by earthen defences. But as the little town acquired a sense of permanence, stone wall defences were built. The earliest are estimated to date to about 1100 and were later augmented and extended in stone by the Normans. The Vikings also threw the first bridge across the Liffey. It was built just beside Átha Cliath – that is, just west and upstream of the walled town itself.

Why there? On the face of it, it would surely have made more sense to connect the settlement directly to the north bank from what is now the end of Winetavern Street, within the walls, on the line of what is now O’Donovan Rossa Bridge (although no one calls it that; it is simply Winetavern Street Bridge to most Dubliners). But to do that might have been to weaken the defences of the town. After all, a bridge can be crossed from either end; had the bridge been built there, it would probably have necessitated a defensive barbican on the south side, which may have been beyond the engineering or financial capacity of the potential defenders. Just as likely, perhaps even more so, is the significance of that proximity to Átha Cliath, because that marked the point at which the Slí Midluachra, one of the four principal roads of ancient Ireland, met the Liffey and by extension the sea. This road ran along the east coast from south Ulster. Its position seems to have accounted for the location of the ford of Átha Cliath – likewise, on the same principle, of the bridge.

So they built their bridge here, a bit upstream of the walled town and beside the old ford. No one knows the foundation date, but a wooden structure appears to have been in position by 1000. The other advantage of this location was that it either opened up or gave access to a pre-existing Norse suburb on the north bank. This was Oxmantown – the town of the Ostmen or east men – which was sufficiently well-established by the late eleventh century to merit its own parish church, St Michan’s. It is no accident that this very first bridge over the Liffey opened up or gave access to a northern suburb. This is precisely what happened on a much grander scale when Dublin bridge-building really took off six hundred years later, in the 1670s and ’80s.

Oxmantown grew in extent after the arrival of the Normans to the city in 1170. As the newcomers began to dominate and bully the existing population of the walled town, many found it expedient to cluster on the north side among their own people, a kind of voluntary ghetto. Indeed, the bridge was referred to in the thirteenth century as Ostmans Bridge, merely one of the myriad names it has had over the years.

This was to be the only bridge over the urban Liffey until 1670. Even then, it was not always there. Although rebuilt at the time of King John in 1214 to replace the old Viking structure, it was dismantled in 1316 and its materials used to strengthen the town’s defences against an anticipated attack by the forces of Edward Bruce – Robert the Bruce’s brother – who had invaded Ireland with the intention of setting up an independent kingdom there. That danger passed and the bridge was rebuilt only to be destroyed by flood waters in 1385. The town decided that it could do so well without it that it was not rebuilt for over forty years, until 1428. But from that date, there has always been a bridge on this site.

It has had many names at different times, including Dublin Bridge – thus echoing London Bridge when that was the only bridge across the Thames. The 1428 structure survived, in various states of repair and disrepair, until it was replaced by the present structure in 1818. It had long been acknowledged that the old bridge had been in ever-deteriorating condition, and it was clear that sooner or later it would have to be replaced. The wonder is that it took as long as it did, because doubts about its safety were voiced as early as the turn of the seventeenth century. So it took more than two hundred years of prevaricating and patching up before the current structure was erected.

It was renamed yet again, this time as Whitworth Bridge, to acknowledge Charles, Lord Whitworth, who was lord lieutenant (or viceroy) at the time. He also had a suburban road in Drumcondra named for him, running along the north bank of the Royal Canal, onto whose southern bank projects the boundary of Mountjoy Prison, opened in 1850; it was here that, years later, Brendan Behan, then serving time for membership of the IRA, heard the ringing of the warden’s triangle to waken the prisoners each morning: ‘and the ould triangle went jingle jangle / all along the banks of the Royal Canal’. Whitworth Road has retained its viceregal name to this day, which is more than can be said of the bridge.

Engraving showing the River Liffey, with the Four Courts and Whitworth Bridge

In 1922, on the establishment of the Irish Free State, it was decided to revert to the simple name of Dublin Bridge. That didn’t last long. In 1938, its name was changed again to honour Fr Theobald Mathew (1790–1856), the great mid-nineteenth-century temperance campaigner. In 1838, he himself took a pledge of total abstinence, saying ‘here goes in the name of the Lord’. He then began a public campaign to wean Ireland off the ravages of alcohol, using the slogan ‘Ireland sober is Ireland free’. This echoed the contemporary nationalist campaigns of Daniel O’Connell.

Fr Mathew’s campaign was an astonishing success, so much so that in the six years up to the outbreak of the Famine in 1845, the revenues raised in Ireland from the sale of spirits fell by nearly 50 per cent.

His successful trespass into this alcoholic territory was impressive by any standard. Ireland lived down to its own caricature: it had an enormous problem with alcohol, not least illicit alcohol. Illegal hootch – poitín – was rife. In south Ulster, ether-drinking was common. Ether, which is a distillate of alcohol treated with sulphuric acid, is required to be adulterated to make it tolerable for human consumption; the adulterate was usually poitín. It was very effective and gave the drinker a tremendous high.

It was a problem that could be contained and ameliorated for a while, but like a dormant volcano it had a nasty habit of re-emerging. By the end of the nineteenth century, with Fr Mathew long in his grave, another priest – Fr James Cullen SJ – felt the need to found the Pioneer Total Abstinence Association, once again to combat the revival of the demon drink. As with Fr Mathew’s campaign, it was hugely successful, and for years it was commonplace to see men’s jacket lapels bearing the Sacred Heart insignia which was the Pioneers’ symbol.

Along with other ostentatiously Catholic causes, its best years were those of the mid-twentieth-century Catholic hegemony, from which the latter-day Irish are now fleeing headlong in secular embarrassment. You’d be pushed to see a Pioneer pin on any lapel these days: it’s seriously uncool. But as recently as the 1950s – that is, within living memory, just – the Pioneers numbered almost half a million people out of a population of just under three million. However, by the early twenty-first century it was back to business as usual. According to the World Atlas, Ireland was seventh in the world in alcohol consumption in 2017, measured in litres per capita. That doesn’t sound too bad until you see the countries that are above it: Estonia, Belarus, Lithuania, Andorra, the Czech Republic and Austria. So ignoring Andorra – too small to be statistically relevant – Ireland has the second-highest consumption rate among countries that never suffered from prolonged Soviet occupation.

Fr Mathew and his clerical successors may, therefore, be regarded as Sisyphean, condemned to an endlessly virtuous futility. You can appreciate why the old bridge was finally named for him. He was important in himself as the progenitor of a huge and significant social movement and, in particular, one so heavily associated with a public projection of Catholic virtue in a hyper-Catholic era. Not that it has done much to enhance his historical memory: most Dubliners couldn’t tell you where Fr Mathew Bridge is. To them, and to all of us, it’s simply Church Street Bridge and there’s an end of it.

This is fair enough, for Church Street – named for the church of St Michan, which dates from the 1090s – has a fair claim to be the oldest established Dublin street outside the walls. Here, in Oxmantown, was Dublin’s first north-side suburb. It is clear from John Speed’s map of 1610 that Oxmantown is well developed, if sparsely in comparison with the walled town south of the river. In the course of time, this suburb would push north along the line of Church Street to embrace Broadstone and Phibsborough up as far as the Royal Canal at the top of Whitworth Road. That was all to come later, in the eighteenth century, as Rocque’s great city atlas of 1756 testifies. Speed’s map is invaluable, however, because it shows the town while it was still a town, before the heroic period of development that began in the 1660s and turned it into the city mapped by Rocque and his successors.

The general point is plain and will, I fear, be repeated quite often in this book, if only because the ineluctable logic of geography proposes repetition: without the bridges, there is no north side, or nothing much worth mentioning. The entire physical development of Dublin – what I referred to in the introduction as the process of northing and easting that turned the town into a city – depends almost completely on the various bridges that are the subject of this study. No bridges, no north side. No north side, no city.

The north side of the river had every advantage for development, most of all rising ground. Much of the land to the south-east of the walled town – the part that eventually ended up as the centre of fashion and desire – was low lying and swampy. But north of the river was all uphill, well above any flood line. And, indeed, once extra-mural development began, it began to the north, across the river. Wealth likes an eminence and could find it here. But even on the north side, development was more focused on the north-east rather than the north-west quadrant, despite the latter having the temporal advantage of Church Street, the longest established main drag. A telling detail in this regard is that in the 1830s almost 900 solicitors – out of a total of about 1,500 – were living in the new north-east residential streets centred on Mountjoy Square. Very few were living west of Capel Street, despite the presence of the Four Courts there. A similar pattern applied to barristers: by 1836, more than a quarter of those who had taken silk were living in Merrion Square, no less – the finest address in the city and even more remote from the Four Courts.1

Church Street led north to Broadstone and to Phibsborough – both developed from the eighteenth century on. It grew to include buildings of distinction – the Blue Coat School, the King’s Inns, Broadstone rail terminus, some churches of modest but definite architectural accomplishment – but it never established itself as a centre of fashion. As we shall see in due course, the process of northing and easting created a sort of fashionable crescent, sweeping in time first from the north-east quadrant and then across the river to the great squares and gardens of the south-east: Merrion, Fitzwilliam and St Stephen’s Green.

All of this left the north-west quadrant, centred on Church Street and its later extensions, something of a fashion orphan. And so it has remained until recently, when a gradual process of gentrification has brought forth a solid extension of bourgeois professionals into the area around Stoneybatter and Manor Street (see chapter 17). Even at that, the city authorities’ ambitious attempt to create a new civic centre based on the long rectangular open space of Smithfield has not been a success – without being an outright failure.

The city just does not want to move west, or at least its beating heart does not. In reality, the western suburbs beyond the Phoenix Park are a vast and depressing sprawl for the most part. It may be populous but the energy and the force is not there, out in the nondescript housing estates either side of the upper Liffey valley.

Yet it is none the less to the west that we turn next. The earlier statement that there was only one bridge over the river until 1670 is only half-true. It is absolutely true of the urban core. But a few kilometres upstream, near the river’s tidal reach at Islandbridge, there was, as the name suggests, a bridge. The first version of it dates from 1577 and it is to it, to its successor structure and to its fascinating neighbourhood that we next direct our attention.

TWO

ISLANDBRIDGE

THE WHOLE INTERPRETATIVE thrust of this book has to do with the process of northing and easting. Thus Dublin grows from a town to a city by expansion from the central southern core around Christ Church across the Liffey to the north side. That’s where it first establishes its city credentials, mainly in the north-east quadrant, before sweeping back across the river to settle the south-east quadrant, which remains to this day the principal locus of fashion and display.