Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ylva Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

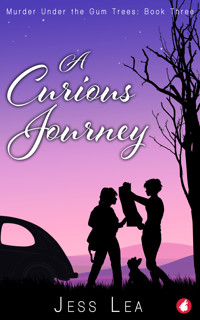

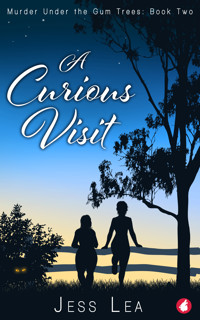

Secrets, scares, and sapphic romance in Tasmania's wilds. Partners in love, life, and earnest museum appreciation, Margaret Gale and Bess Campbell desperately need a break. Strict, meticulous ice queen Margaret has been fired for frightening her auction house customers, while free-spirited Bess hates her office job. While holidaying in Tasmania, they receive a call for help that leads them to a creepy, old house in the wilderness. There, they meet a mysterious woman from Margaret's past, who warns she's being stalked and something terrible is coming. What's going on? What secrets lie within Crossroads House? And why on earth are there hidden cameras around the grounds, recording everything that happens? Unexplained incidents turn sinister, endangering Bess and Margaret—and their trust in one another. But they don't give up easily… This sweet, eccentric sequel to A Curious Woman can easily be read as a standalone story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 456

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table Of Contents

Other Books by Jess Lea

Acknowledgements

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Other Books from Ylva Publishing

About Jess Lea

Sign up for our newsletter to hear

about new and upcoming releases.

www.ylva-publishing.com

Other Books by Jess Lea

Looking for Trouble

Murder Under the Gum Trees

A Curious Woman

A Curious Visit

Anthology

The Taste of Her – Vol 1 (e-book)

The Taste of Her – Vol 2 (e-book)

The Taste of Her – A Collection of Ten Erotic Short Stories (paperback)

Acknowledgements

Thanks to everyone at Ylva, especially Astrid, Lee, Julie, Jenny, and Daniela, who were so supportive of this sequel. Thanks to Rach for demanding more of “maritime Margaret”! And thanks especially to my partner, Sam, for reading the drafts with such care and enthusiasm, talking me through my dilemmas, and refusing to hear any notion of quitting.

Dedication

For Jenny and David, who made us very welcome in Tasmania.

Chapter 1

Bess Campbell adjusted her rainbow coat made of recycled plastics, then pulled on her emerald-green woolly hat. She’d knitted it herself in the shape of a Viking’s helmet, and it made a striking contrast with her red hair. If there were spirits haunting this place, why not give them some colour to enjoy? They spent enough time in darkness.

She said that to the guide leading the ghost tour, but he gave her a funny look.

The guide shone his lantern at the display wall. It was engraved with names: Martha. Maria. Susannah. Eliza. Ann. Few other details were known. She wondered what it said on the women’s tombstones, if they had them.

Shivering, Bess thrust her hands into her coat pockets and stamped her feet against the flagstones. No moon tonight. Icy breezes whipped across the yard, plastering her skirt to her legs. Normally, Bess liked being outdoors; she loved nature, found it invigorating. But she wasn’t sure about this place.

The prison walls were high, made of rugged sandstone. Weeds grew through the cracks. Behind her was the site of the old punishment cells. They had no windows, just small, rough vents too high to see out. Women condemned to those cells had to climb down underground, into the earth.

“That was a lesson,” the guide explained, “to show them where they were headed in the next life if they kept breaking the rules.”

There had been a lot of rules in the women’s penitentiary built here in Tasmania in the 1820s, back when the island off Australia’s mainland was still called Van Diemen’s Land: an infamously wild, cold, and dangerous prison colony at the edge of the world.

A woman could be punished for not working hard enough when washing laundry with frozen hands. She could be punished for swearing, or falling asleep in chapel, or eating more than her share of bread, or sharing her sleeping hammock too enthusiastically with another woman.

Talking was discouraged too. Visitors to the prison remarked on how the women and children moved about the place in silence, like ghosts.

While the story disturbed her, Bess longed to see a ghost. Or a bunyip or a UFO—anything unearthly and hard to explain. She’d always been drawn to the colourful side of life, to anything whacky, creative, and eccentric. That was why she had moved to the kooky small town of Port Bannir three years ago—to work in a quirky gallery and live in a tiny house in a field.

But then her lovable boss had been killed and the gallery taken over by new managers who didn’t like Bess at all. A year ago, they’d transferred her to the promotions team in their Melbourne office.

While city life was convenient in some ways, Bess knew her employers were sidelining her. After months of spreadsheets and Zoom meetings, her spirit felt starved. She missed her old job. She missed her beloved chickens, now living with her brother. Most of all, she missed the sense of adventure she used to feel every day.

This trip around Tasmania might help. Bess needed wilderness and beauty and strangeness in her life again.

The guide held up his lantern. “Through here were the nurseries. Hundreds of babies were kept crowded inside, neglected and half-starved. Those who survived were snatched from their mothers and sent away to the orphan school. They say some nights, when the wind blows down from the mountain, you can hear the screaming.”

Bess pulled her coat tighter, her skin creeping. Maybe she didn’t want to meet the spirits of this place after all. Could suffering, despair, and anger be so strong that they left an imprint on the locations where they occurred?

The guide began to talk about the women who’d been imprisoned here—thieves, poisoners, arsonists—and the sinister matrons who controlled them.

“You see where that cell is marked on the ground at the end? Once we had a blind visitor whose guide dog refused to go inside. And over there by the staircase? People complain that the photographs they take of that spot don’t turn out. All they get is a dark image.” The guide lowered his lantern. “I brought my daughter here when she was five. I left her alone while I went to fetch something. When I came back, I found her crying. She said a woman in black had been angry with her. But there was no one there but us.”

A door banged. The woman beside Bess jumped and let out a muffled shriek. The guide’s lantern swayed, light and shadows lapping across the walls. Footsteps rang out against the flagstones.

The guests bunched up together like an anxious herd. Those footsteps were coming closer. People whispered, “Is this part of it?”

Bess stepped forward. She didn’t want to miss anything.

The gate to the yard flew open. A black silhouette stood against the gloom. She was tall and lean, and the air around her seemed to hum with a strange energy.

In the dim light, her face appeared as white and angular as fresh-cut marble above her black clothing. Her features were strong with a certain stark beauty; her eyes were shadowy, her hair jet black. Her long fingers flexed as if searching for a neck to wrap around.

She stepped forward. Her gaze swept the crowd, her dark eyes glinting malevolently. “Would the owner of a blue Nissan Pulsar, numberplate XIR679, move it immediately, as it is taking up two spaces.”

Bess bit her lip, fighting not to laugh.

“If you’d done that at my museum, you would have been banned,” Margaret Gale said.

* * *

“You missed a good start to the tour while you were parking the car,” Bess told Margaret. The group, slightly shaken, had moved on to examine the matron’s cottage. “Thanks for dropping me at the entrance.”

“I wouldn’t have needed to, if certain people had learned basic driving skills.”

“Do you think it could make a good topic for a gallery exhibition? Haunted prisons of Australia?”

“Plenty of source material.” Margaret brushed a speck from her long black coat. She knew a lot about colonial relics, having once run a museum full of them.

Bess and Margaret had loathed each other back in Port Bannir when they first met. They were professional rivals with very different views on how to manage a gallery. Bess had thought Margaret a snarling control freak who needed to move with the times, while Margaret had considered Bess an incompetent, irritating hippie. It had taken them some time to recognise how much they both looked forward to their arguments and how much they really had in common.

“Haunted prisons are a scam, though,” Margaret said now. “When I was locked up for murder, I didn’t meet any ghosts.”

A pleasant-looking family turned around to stare at her.

Bess rushed to explain. “It was a false accusation; she was released…” It was hard to sum up quickly what had happened in Port Bannir.

The parents hurried their children away.

Unperturbed, Margaret examined the cottage door. Her indifference to what other people thought of her was a quality Bess found both attractive and maddening.

Someone’s phone sounded, disrupting the guide’s speech.

“They should bring back the punishment cells for that.” Margaret did not bother to lower her voice, despite Bess mouthing, “Be friendly!”

Margaret’s refusal to compromise and play nice was another thing that frustrated and occasionally delighted Bess.

As the group moved forward, Margaret said, “You’re still thinking about new exhibitions for that gallery of yours, then?”

“It’s not mine.” Bess pursed her lips. “My manager hasn’t let me make any decisions about exhibits in months.”

“Which is why all their recent shows have been abysmal.” Margaret might be bad-tempered, but she had always been loyal.

“Thank you.” Bess took her hand, ignoring the way Margaret stiffened and seemed to stop herself from pulling away. Margaret never minded when people thought her odd, but public acts of affection were foreign to her. It was one of the things they’d agreed to compromise on, just as Bess had agreed to respect Margaret’s detailed systems for bookshelf arranging and sock folding.

She squeezed Margaret’s long, cool fingers, touching the nails which were filed back smooth. “Are you enjoying our holiday?”

“I’m enjoying the ruins.”

“Wait till you see what I’ve got planned.” Bess knew she sounded overeager, but the past few months had been hard.

When she and Margaret had got together at last after many misunderstandings and some dangerous adventures, Bess had assumed they’d earned their happily ever after. Instead, real life had intruded once again: frustrations at work, changing living arrangements, family tragedy. She didn’t regret any of the time they’d spent together, but she wished it could have been smoother sailing.

They needed a break, a reset. Bess was determined that they would enjoy it. “I’ve got our itinerary planned. There’s lavender ice cream, llama walking, a petting session with Tasmanian devils, a honeybee encounter…”

“As long as I don’t have to do all four at once.” Margaret looked as if she would be happier lurking around another crumbling old prison, but Bess wasn’t having that. Ghosts were interesting, but life had to be lived too.

She gripped Margaret’s hand tighter, willing the warmth from her own skin to flow into her partner’s.

They followed the tour group outside again.

The guide explained, “Over there is the site of the old infirmary. It was freezing, dirty, and damp—you were more likely to catch a disease than be cured of one. Sometimes, on a still night, you can hear the sound of nails being hammered into wood as if someone were making a cheap coffin…”

Bess flinched and glanced at Margaret, who didn’t seem to react. Until a message beeped on Margaret’s phone, cutting through the quiet.

People turned to stare.

“Seriously?” Bess hissed as Margaret turned her phone to silent, the muscles in her face working in repressed embarrassment.

“It may have slipped my mind,” Margaret whispered without moving her lips.

“Who is it?”

“Hmm.” Margaret frowned at her screen. “Not a number I recognise.”

The guide finished and invited everyone to explore the compound. “But be sure to leave before ten because that’s when I lock up. And trust me, you don’t want to spend the night alone in here.”

A group of tourists ventured over and asked with big, hopeful smiles if they could take a picture with Margaret.

“No,” said Margaret. She stalked off to look at a display of historic manacles.

Smiling as hard as she could, Bess was left to explain to the tourists that Margaret was just another visitor, honestly, and not an actor playing a ghost at all.

* * *

Margaret could barely see the road. Her headlights lit up a few metres of bitumen rolling out like a conveyor belt, but there was no telling what lay beyond. A fallen tree? A car accident? A kangaroo springing from the bushes about to hit their windscreen? She cursed herself for agreeing to a late-night tour and a motel outside of town. She’d grown up in the country and should have known better.

The road was lined by murky shapes: bracken, tree stumps, dead animals swept aside by logging trucks. This island was lush and beautiful, but it was also the roadkill capital of Australia.

“You’re smouldering again.” Bess turned up the heater.

Margaret’s fingers began to thaw. “I’m concentrating.”

“I know a smoulder when I see one. It’s like I’m travelling with Lord Byron, if he used colour-coded packing cells in his suitcase and wiped down the whole motel room with disinfectant.”

“Do you know what people do in motel rooms?” Margaret shuddered. “You’ll thank me when you don’t get giardia. I can’t believe you nearly drank out of one of their mugs.”

“Your flying tackle to stop me was impressive,” Bess said. “You’re a great loss to women’s rugby.”

“Thank you.”

“Please tell me you’re enjoying this trip a little.”

“I always enjoy your company.” How strange to think that she had once considered Bess the most aggravating woman she’d ever met. Nowadays, Margaret could not imagine being without her.

She thought back to a hike they’d taken yesterday near Cape Raoul at the southern end of the island. Bess had led the way to the lookout point over the jagged cliffs. The sea foamed and churned far below.

Yelling “Wow!”, Bess had scrambled over the rocks to get closer, until a massive gust of wind blew her coat out like a sail and Margaret had to haul her to safety, Bess laughing in delight. Her freckled cheeks were pink, her red curls damp under that ridiculous Viking hat, her buxom body panting from exertion.

Margaret wondered yet again where this woman got her energy from. It’s not like me to be this lucky.

It reminded her of the way she’d felt when she and Bess had first got together two years before. A startled, unexpected joy, a sense that the future might indeed turn out to be better than the past.

Then new problems had come crowding in, and little by little, that lovely optimistic feeling had been tugged away. Could she recover it again out here?

Bess said, “How about that sea yesterday? Majestic!”

Margaret didn’t dare take her eyes off the road. But she breathed deeply, inhaling the scent of the other woman’s organic shampoo, a light herbal aroma. Bess always smelled like a garden.

Her tone a little too casual, Bess added, “I wouldn’t mind being buried at sea. To return to the elements, become part of that wild, primal energy… When you think about it, it’s the most spiritual way to go.”

“Humph.” Margaret knew what Bess was hinting at: a brass urn sealed in plastic and stowed with care in Margaret’s locked suitcase.

She wasn’t sure why she had brought the urn with her, except that she didn’t like to leave it at home. You heard of burglars breaking into houses while the owners were on holiday and trashing everything. And Tasmania wasn’t such a bad place to take someone’s ashes. Her family had gone on a trip here once when Margaret and her sister Deirdre were children and their mother was still alive, before things went wrong for the Gales once and for all. Margaret couldn’t remember much about that holiday, but she thought Deirdre had enjoyed it.

Still, she wasn’t prepared to have the conversation Bess had been dancing around, about what to do with Deirdre’s ashes. Knowing Bess, the conversation would involve a lot of talk about workshopping, healing, and radical acceptance. Probably with some moonstones and rose quartz thrown in.

Margaret didn’t scorn the idea as she once would have. Actually, it gave her a kind of tender pain to know that Bess cared. But she couldn’t think about those things now. She’d spent enough time organising Deirdre’s funeral, managing her will, closing her bank accounts, paying her medical bills, sorting through her belongings…all the bureaucracy of death. She couldn’t give any more time to that tonight.

Changing the subject, Margaret said, “Not a bad tour this evening, despite the silly ghost talk. Some of the displays needed updating, though.”

Bess sighed. “You must miss your own museum.”

“I never think about it.” Margaret cringed at the obvious lie. That museum had been her life’s work: a bluestone nineteenth-century courthouse filled with artefacts from sailing ships, the whaling industry, and Antarctic voyages. She’d devoted each day to the history she loved and the tourists she hated, and it had given her life structure and discipline. When developers had forced her to sell the place, she had managed to negotiate a good price, but it left her feeling like she’d lost a limb.

As if she’d heard Margaret’s thoughts, Bess said, “Do you think that’s why you struggled when you went to work for that antiques auction house?”

“I did not ‘struggle’.” Margaret sniffed. “If I told people the truth about what their grandparents’ old junk was worth, and if I refused to sell preposterous figurines of television characters, that wasn’t struggling. It’s called having professional standards.”

“I thought it was called getting sacked.” Apparently even Bess could only put up with Margaret’s snapping for so long.

“I was not sacked. It was a mutual separation.”

But where she would head next, Margaret had no idea. Changing careers at her age? And right now, when all the world apart from Bess seemed so foolish and irritating, so poorly run and badly designed and…grey? Her vision blurred and she blinked hard. Don’t you fall asleep.

Something burst from the darkness and shot across the road. Margaret stamped on the brake.

The car screeched to a stop, jerking them forward and back.

Bess gasped.

The bushes waved on the side of the road as a long tail slipped inside and vanished.

“God.” Margaret squeezed the steering wheel. “Are you all right?”

“I’m fine.” Bess loosened her grip on the seatbelt.

Recalling Bess’s history with car accidents, Margaret berated herself for her carelessness. “I’m sorry. It took me by surprise.” Her voice shook. “What was it—a cat?”

“A possum, maybe.” Bess pressed her face to the window, but nothing moved in the darkness.

“Terrible driving,” Margaret said, angry with herself. “I put you in danger. I should have hit it.”

“No, you shouldn’t.” Bess gazed out into the night. “Do you think it could have been a quoll? Those spotty animals with the fluffy tails and the pretty little faces?”

“I’ve no idea.” Margaret got the hire car moving again, driving slower than before and scanning the road until her eyes watered. The rush of adrenalin had left her jittering.

No more country driving after dark, she decided as she turned into the motel carpark. It wasn’t safe.

Still, as she climbed out of the car, she felt a rush of dizziness so intense she had to clutch the door handle. She’d been so lifeless for so long. Was it possible that what Margaret secretly craved was not healing and peace but a little bit of danger?

* * *

In the motel room, Bess gathered up her silver spotted pyjamas and cruelty-free toiletries while Margaret checked her phone. There was an email from a neighbour who’d been collecting her mail: two more bills had turned up in Deirdre’s name. One was from an insurance provider who explained they could not close her account until the account holder contacted them personally. Margaret gritted her teeth. She would call them tomorrow and ask if they had a Ouija board. The other bill was from a phone company whom Margaret had informed about Deirdre’s death. Their computer system had addressed it to “The Deceased”.

And she had a missed call and voicemail from that unfamiliar number again. They must have come through during the ghost tour after she’d switched her phone off.

“Everything all right?” Bess stood in front of the bathroom mirror, brushing out her thick, wavy red hair.

“Another call.” Margaret studied the number. “Has Deirdre’s oncologist thought of one more charge to add to the bill? Or are her cretinous in-laws ringing again to ask how much money she left them?”

“At this time of night? Probably a wrong number.” Bess took out her toothbrush. “Hey, I’ve been thinking: do you reckon we should get an Asian-style squat toilet installed at our place?”

Margaret put down her phone. “What are you talking about?”

“I’ve been reading this amazing book about gut health and good bacteria, and it says the best position is actually—”

“I withdraw the question. And absolutely not.”

“You’re so conventional,” said Bess around a mouthful of toothpaste. “Well, do you think I should become a foster mother for rescue goats? I’ve been reading about that too.”

“Oh, that’s easier.” Margaret checked their maps for tomorrow. “No.”

Bess spat out her toothpaste. “Have it your way.” She arranged her vegan cosmetics along the sink, nudging too close to Margaret’s toiletries.

“We said you would keep your things on the left-hand side.”

“Fine.” Bess moved everything farther away, although she made a point of leaving her cactus and kale recovery lotion next to Margaret’s toothbrush.

Margaret narrowed her eyes. “Are you trying to provoke me?”

“Play your cards right…” She grinned, then pulled Margaret down for a kiss.

Margaret stiffened in surprise, then returned the embrace.

Bess pressed her warm, full body up against her, sliding her arms around Margaret’s waist.

The tension in Margaret’s muscles began to seep away, as though she were sliding into a soothing bath. She felt Bess’s lips moving as she smiled, felt the laughing flutter of her breath. Her kisses were often like this: light-hearted, joyful. Disarming.

That was not a thing Margaret was used to—not a thing she had ever wanted before she met Bess. Could one person change you that much?

A few minutes later, while Bess sang Dolly Parton songs under the shower, Margaret decided to stretch her legs. She should check that message too.

The night sky was clear, the air crystal-cold and scented with eucalyptus. In the bushland behind the motel, things rustled and crunched and squeaked.

“Margaret?” She didn’t recognise the woman’s voice in the recorded message. But there was something about it—an alto pitch, crisp consonants, a slight breathiness—that made her listen hard.

She thought she had heard that voice before, a long time ago.

“I hope you’re the right Margaret Gale,” the voice said. “Otherwise some poor stranger is about to be confused…” A quick note of laughter, like a bird’s cry. Margaret frowned. Again, there was something familiar about it.

“You might remember me,” the voice went on. “We met on graduation night, 1997. Vivienne Bolt.”

Margaret froze. Her breath hung in the cold air.

“I’d love to do all the what-have-you-been-up-to-all-these-years guff,” said the voice, “but Ivy, my grandmother, has fallen asleep at last and I don’t know how long I’ll have. So I’ll cut to the chase.”

Margaret gripped the phone. She remembered that voice now, with its rounded vowels and hint of an English accent, although Vivienne had been born and bred in Australia.

Back on graduation night when they’d met, Margaret had asked Vivienne about her unusual way of speaking. “Snobby relatives,” was Vivienne’s reply, “and the most God-awful elocution teachers at boarding school. Two-hundred-year-old harpies who hit us with walking sticks—truly! God forbid we should sound local.” Her white-blonde hair blew in the night breeze, the black shapes of trees in Melbourne’s Alexandra Gardens behind her. In the lamplight of the gardens, Vivienne’s pale skin had an eerie glow. “I’m not from any country,” she laughed, and Margaret had thought of sprites, of mermaids.

Now Margaret stood motionless as the past returned without warning, slicing through the present.

Vivienne’s message continued: “I looked you up online and phoned your employer. By the way, their silly receptionist really shouldn’t give out phone numbers to any nicely spoken lady who calls claiming to be an old friend. I wanted to ask your advice about something, but they said you’d left and were travelling here, and I thought: perfect!” That laugh again. “For me, I mean.”

She cleared her throat. “Margaret, I need a favour. My grandmother is ill and I’m staying at her house at seven Renfeld Lane, outside a town called Mount Bastion. You won’t have heard of it; it’s rather a dump. But… Well, strange things have been happening.”

Margaret held her breath. Strange was right. Vivienne Bolt calling her? Vivienne, whom she had imagined long gone, whisked away twenty-five years ago? How could Vivienne be here in rural Tasmania of all places?

The voice said, “I’m afraid this will sound completely barking, but I promise I’m compos mentis. It’s just… I think someone is trying to harm us. My grandmother has a large antique collection; all her money is tied up in it. Ghastly things, but valuable. I’m trying to sort out her finances to make sure she’s looked after because she’ll need to go into care soon. She’s getting worse, poor old girl, and there’s only so much I can do.”

A pause.

“But things have been going missing. A silver-plated Art Deco cigarette lighter, a porcelain nymph, an amber paperweight. Things small enough to slip into a pocket. I noticed it this week when I was cleaning her disaster of a house. And now I wonder how many other things have been swiped!”

Vivienne took an audible breath. “It’s not just the thefts. Someone scared away the two carers I hired to help look after Ivy. One of them left after her car tyres got slashed three times in our driveway, and the other quit when she found a piece of glass in a sandwich she’d left for herself in our kitchen! And— Look, I know it’s a drafty old building and perhaps I’m letting the atmosphere get to me, but sometimes I swear I hear noises. Something moving around in the house. It makes my skin creep.”

She laughed again, this time a little desperately. “I don’t dare report it. Ivy would have a fit if she knew; she’s so ill, and she’s devoted to her collection. And this is a small town. Ivy relies on the local businesses for groceries, medication, transport. If the police started questioning her neighbours, things could become very difficult.

“Listen, Margaret, I’m thoroughly embarrassed to call you out of the blue and drop this in your lap, but I remembered how you said you planned to start your own museum one day, so I did some research into you. I hope that’s not too intrusive, but you must know there are intriguing stories online about a museum you used to run. It’s clear you know a lot about antiques, and you’re a—a friend of mine. Could you stop by? Look over Ivy’s collection, help me do an inventory, figure out the extent of the loss, advise me on what to do? It would be ever so useful. And perhaps…perhaps with your brains, you might be able to figure out what’s happening.”

Vivienne exhaled. “Listen to me blathering on! Are you still listening? I know I’ve got no right to ask you for anything after all this time, but…I’ve got nowhere else to turn, Margaret.”

A computerised voice took over: “To return call, press two. To replay message—”

Margaret hung up and stared into the night.

A bloodcurdling screech ripped through the darkness, making her jump. There must be a masked owl in the bushland nearby. It was a sound that had always made her think of witches.

Chapter 2

“But who is this Vivienne?” Bess asked the next morning.

Margaret’s jaw was firm as she drove, her eyes narrowed in concentration. But since that was her resting face, it didn’t tell Bess much.

“I met her at university in Melbourne. Or rather, the night after I graduated from university. She’d done her honours in fine arts and was about to head to Rome on a scholarship.”

“Nice work, if you can get it.”

“We skipped the graduation party because everyone else was drunk and obnoxious,” Margaret said. “We went for a walk around the city and along the Yarra River instead. Then we went our separate ways and I never heard from her again. Strange that she would contact me now.”

Bess thought there was something curious about Margaret’s tone. Did she sound distracted? Vague, even?

Still, Bess was determined to make the best of things. “Well, it’s a mystery. Let’s go and solve it! I’m always up for an adventure, and I like meeting new people. It puts water back in my well.”

“Here we are.” A sign directed them off the highway towards Mount Bastion.

This town had not been on Bess’s list of places to visit on their Tasmanian holiday. As they pulled onto the main street, she could see why. Some parts of Tasmania were heaven for tourists, with breathtaking views, fluffy native animals, fine wine, and gourmet food, but Mount Bastion was not one of those places.

Instead, the town had a general store, two dilapidated pubs, a tatty-looking Chinese restaurant, and a community centre whose sign said Open Most Tuesdays. No school or doctor’s surgery. Whatever industries had once sustained the area were long gone. Port Bannir had been like Manhattan compared to this.

Incongruously, there was an antiques shop in an old Edwardian building. She wondered where they found customers.

As they drove down the quiet street, two locals turned to watch.

“Shall we find somewhere to have lunch? Or did your friend invite us to eat with her?”

“She’s not my friend,” Margaret said. “I told you, it’s been twenty-five years. And no, the message about theft and sabotage didn’t mention lunch. But given the broken-glass-in-the-sandwich story, I’d suggest we buy something in town.”

One pub was shut. The other bore a sign: Kitchen closed due to illness.

Seeing Margaret raise her eyebrows, Bess said, “Let’s try the general store.”

When they pushed open the doors to the shop, the people inside turned to stare. Bess saw their own reflections in a fridge door. Margaret was tall and thin, her short dark hair slicked back. She was clad in black, including black leather boots and matching gloves. Bess was short and plump, and wore cats-eye glasses, a jacket in psychedelic patterns, and a hand-knitted hat in the shape of an octopus with tentacles streaming down her back.

The place fell silent. If a piano had been playing, it would have stopped.

Bess took two juices from the fridge and made a point of smiling as she approached the counter. After all, the energy you put into the world was the energy you got back. Most of the time.

“Petrol station’s down the road,” someone blurted out. “They sell maps, if you’re lost.”

“Thank you.” Bess kept smiling. “But we are exactly where we want to be.”

Margaret ordered a sausage roll in a less friendly tone. Then she said quietly to Bess, “Do you mind us stopping here? I don’t know what’s happening with Vivienne. But we won’t stay long.”

“Of course I don’t mind. I love new places, new people…” Bess turned to the woman behind the counter. “Are any of your pies vegetarian?”

The woman stared at her as if she’d ordered peacock tongues in jelly. “No.”

Well, maybe not all new people. Bess ordered a pasty that looked fossilized, her tone a little less perky now.

She turned back to the counter. “We’re looking for number seven, Renfeld Lane. Do you know—?”

“Nope.” The reply came before she’d finished asking. The woman busied herself at the register. When Bess looked over her shoulder, everyone else seemed engrossed in other things.

While Margaret paid, Bess studied the community noticeboard near the door. There were ads for sheep dip, pest exterminators, mental health crisis lines, and a Rotary Club dance scheduled for that night. And a large poster, tacked over the top of several others. It showed a portly man with long silver curls, a leather Akubra hat, a swirling scarf, and a smug look.

“Dorian Visser LIVE. Local writer in residence reads from his critically acclaimed work, Crossroads House: Inside Australia’s Most Haunted Homestead”.

She was about to call Margaret over when a message sounded on her phone. “Oh wow.”

“Good news?”

“Yes!” Bess caught herself. “Well, no. Our chief curator has broken both legs skiing, just when his second-in-command went away on maternity leave.”

“My sympathies to them both.”

“But it’s left the gallery short-staffed.” Bess chewed her lip. “And they need to start planning next season’s exhibitions.”

“Really? Perhaps now they wish they hadn’t spent months turning down your ideas and inventing meaningless tasks to keep you busy.”

Bess studied the message. “This could be my chance.”

“After how they treated you, they don’t deserve to benefit from your hard work and talent.”

“Maybe not, but I can’t quit right now, can I?” Bess spoke without thinking, then regretted it. She didn’t mean to make Margaret feel as if her own unemployment was forcing Bess to stay in a job she hated just to pay the bills—although there was some truth in it.

“If I could get one more strong exhibition under my belt, I could leave on a high note,” she continued. “It would look great on my résumé, and it would make me feel better about my time there. Plus it would make those bozos realise how wrong they were to take me for granted.” It wasn’t good karma to dwell on bitter thoughts, but you had to give yourself permission to be imperfect sometimes. “So stuff ’em.”

Margaret shifted from one pointy-toed boot to the other. “I am…sorry. The way your employers have treated you has been unacceptable. And it started because of me.”

When Bess’s previous boss, Leon, was stabbed to death in his own gallery, many people in Port Bannir had assumed Margaret, his business rival, was responsible. Bess’s new employers had been happy to go along with that explanation, and they had not liked it at all when Bess had believed in the woman’s innocence and set about proving it.

She grasped Margaret’s arm, feeling the sinewy strength there. “Totally worth it.”

Through the shop window, she sensed several people staring as she craned up to kiss Margaret firmly on the mouth.

And stuff you too, she felt like calling back over her shoulder. But she managed a big, joyous smile instead. Living well was the best revenge.

“Now let’s go and meet Vivienne. I can’t wait.”

* * *

“Oh boy,” Bess said fifteen minutes later as they pulled up outside a set of high iron gates that must have been elegant a hundred years before. Now they were half swallowed by creepers. Welded into the gates were the words Crossroads House.

The property backed onto a national park and was framed by blue gums, blackwoods, and silver banksia trees. The grounds of the house must have been pretty once, but now the lavender bushes and hollyhocks were fighting for survival against blackberries and weeds.

Bess felt sorry for places like this. They made her want to jump the fence with some garden shears, a shovel, and a sack of organic mulch.

“What…?” Margaret stared, her mouth hanging open. “She can’t live here?”

The house was a ramshackle old mansion with sagging gable windows, moss covering the roof, and paint peeling off the pillars that held up the front porch.

Trying to stay positive, Bess said, “Well, it’s got character.”

“It’s got termites.”

“Come on, it’s interesting.” Bess always defended the downtrodden, even houses. “What would you call that architecture?”

“Criminal?” Margaret winced. “I can see it’s been altered a few times. Stolid Victorian manor farm meets Edwardian new money, meets Art Deco hangover, meets whatever they were thinking when they added those gargoyles.”

“But if the owner fixed it up, it could be worth a lot of money.” Bess led the way through the gates. “I wonder why she hasn’t?”

“Perhaps I got the address wrong.” Margaret hung back. “Vivienne wouldn’t live somewhere like this.”

“Don’t be silly. It’s just a building.” Bess pressed forward along the gravel path that was overgrown with flatweed. As she neared the entrance to the house, she said, “Places only seem good or bad because of the meanings we attach to them. If we can let go and just breathe into the moment—”

“In that house? We’d breathe in black mould.”

“—then we can calm those judgemental thoughts and accept things as they are,” Bess finished, pitching her voice loud enough to cover Margaret’s disbelieving snort. “Try a one-minute meditation with me.”

“No, thank you.”

“You can’t spare one minute?” Bess had reached the front steps but saw no reason to rush. She shut her eyes and spread her arms wide. “Right now, I’m wriggling my toes and noticing the ground underneath me.” The awareness made her smile. “I’m becoming conscious of my breathing and how each breath is different from the last, like the moments of our lives.” She shook her shoulders to loosen any tension. “And I’m repeating to myself, ‘I am safe, I am loved, I am forgiven’.”

She knew Margaret would dismiss this as hippie nonsense, but Bess wished she would not. If Margaret could bring herself to believe those things, surely she would be happier.

Finishing with a big, delicious exhale, Bess spun around to demonstrate how much better one minute made her feel. She caught her foot in a rabbit burrow, toppled, and sat down hard on the gravel, crashing into a heavy object that tipped over, drenching her in something wet, cold, and smelly. The object hit something else, which shattered.

Water soaked through her clothes; she had fallen over a birdbath. Evidently no one had cleaned it in a while, and she was spattered with pond scum and slimy leaves. The birdbath had broken in two when it hit the other object, which looked like it might have been a garden statue. A nymph maybe? There wasn’t much of it left.

Margaret helped her up. “Are you hurt?”

“I’m fine.” Bess looked down at the broken items. “But that’s not good.”

“I’d say you did a few hundred dollars’ worth of improvements.”

The front door of the house opened. Two women appeared in the doorway, one in a wheelchair. The younger one was slender with piercing green eyes and long white-blonde hair pulled back. She looked to be in her forties, but her skin was flawless and very pale as if she had never been allowed outdoors. There was a delicate air about her, but her sharp cheekbones and pointed chin hinted at a kind of strength.

The other woman must have been past ninety. She was stick-thin, her body shrunken and hardened as if life had drained the juices out of her. Her brittle white hair was yanked back and skewered to her skull with an expensive-looking silver pin. Matching silver pendant earrings dragged her withered earlobes down towards her shoulders. Her hands, gripping the arms of her wheelchair, were gnarled and veiny but looked like they had once been strong.

The two looked like a very old but powerful witch and a sad fairy held prisoner by her spells. They stared at Bess as she stood next to their broken ornaments, drenched and dripping slime from her octopus hat.

In a voice that sounded like a deep croak, the older woman said to the younger one, “Get rid of them. You know I won’t have people here.”

The younger woman flinched as if she knew the rules only too well.

* * *

Margaret felt as if she’d put her weight on a step that wasn’t there. The younger woman was Vivienne?

For twenty-five years, her memories of Vivienne had run on a loop in some darkened cinema at the back of her mind. Vivienne smoking French cigarettes without filters, her hair gleaming like platinum under the wet streetlight. Vivienne talking about the Louvre, the Tate Modern, the Uffizi, her young voice world-weary as she explained that they were all right but not what they used to be—now, the Buchmann Galerie in Germany, that was interesting, cutting edge. She wouldn’t mind going there.

She and Vivienne had walked along the wall of the moat outside Melbourne’s National Gallery, looking over the darkened city with cheerful disdain. Below her in the water were hundreds of coins tossed in for luck, now wearing away. “People are such sheep,” Vivienne had said. “You have to make your own luck.” The wall sloped higher until her lace-up high heels were level with Margaret’s heart. Margaret had held out her arms to help her jump down.

How could Vivienne be here?

During those twenty-five years since graduation night, she had wondered sometimes what Vivienne was doing. The young Margaret had pondered the question while she struggled along in junior curator jobs whose pay mocked her education and ability. And later on she’d wondered about it again as she worked to set up her maritime museum while battling a hostile town and caring for an ageing, angry father.

It had cheered her up in a strange way to picture Vivienne poring over medieval manuscripts at the Vatican or restoring seventeenth-century folios of Shakespeare’s plays in the British Library. Still looking poised, chic, and somehow otherworldly as if these expert jobs would suit her well enough until a better opportunity arose. Perhaps to become an advisor to some top-secret government agency or marry into minor royalty.

Never would Margaret have imagined Vivienne living in a rotting old house in a town much shabbier and lonelier than Port Bannir, caring for an elderly relative who seemed worse than Margaret’s dad.

This was all wrong.

She felt thrown off balance and, quite unreasonably, betrayed.

* * *

“Please don’t feel dreadful,” Vivienne said for the fifth time.

Bess, who believed you should apologise for accidental breakage once, then pay for repairs and move on, longed to reply I don’t, but clearly you think I should.

The visit was not going well.

Breaking those garden ornaments had been a bad start. Vivienne had insisted on lending Bess some dry clothes, which was nice of her, in theory. Then she fossicked through her wardrobe, pulling out size-eight garments that wouldn’t fit before handing Bess a frilly pink robe (“antique Edwardian peach lace,” she’d said) which clashed eye-wateringly with Bess’s red hair.

Not that Bess believed in body anxiety or restricting women’s colour choices. But she suspected that Vivienne did.

If Vivienne was subtly unwelcoming, there was nothing subtle about her grandmother. When Ivy wasn’t squinting at Bess through cloudy eyes and barking loudly, “Who’s the blob with the red hair?” and “Why did you let her break my things?”, she was grabbing at Vivienne and snarling, “Who are you anyway? Where’s my Viv?”

“I’m sorry about her,” Vivienne whispered to Margaret. “Her pain medication makes her confused.”

Which was terrible, of course. Bess tried to feel pity for them both.

Despite its rundown exterior, Crossroads House was neat and functional inside. It needed repairs—there were patches on the walls covered in rough plaster, and the furniture looked at least eighty—but the two women seemed to live here comfortably enough. There was a stairlift installed against the wall by the staircase to transport Ivy up and down.

Bess spotted an alcove in the wall at the top of the stairs. It held a display pedestal with some item in a glass box. She squinted. “Is that an animal’s skull?”

But her companions had walked on.

The walls of the entrance hall were decorated with black-and-white photographs of the property in its heyday. Cattle grazed in sunny fields while workers hurried around, filling carts with timber and stone. In those pictures, Crossroads House was new and ostentatiously wealthy—every roof tile and brick seemed to gleam. People posed in the driveway next to vintage cars: men in three-piece suits and waxed moustaches, women in Edwardian lace and enormous hats.

Where had it gone, all that bustle and success?

Ivy snapped at Vivienne, “Why would you invite strangers here? You know we don’t do that.”

Bess wanted to ask Why don’t you? But after the birdbath incident, she didn’t think she should cause further tension.

Maybe Ivy was worried about protecting her antiques. The place was full of them. Delicate brass and enamel carriage clocks bonged on the sideboard, and blue and white Chinese vases sat on occasional tables. Dainty porcelain shepherdesses peeped out from glass cabinets.

Bess knocked over two brass statuettes and an umbrella stand. She wasn’t really clumsy, but she was used to living in a tiny house furnished with sturdy, brightly coloured things she’d made, knowing that if they got broken, she could mend them or turn them into something else.

What was the point of living in a gigantic house and tiptoeing around your own belongings?

Still, she could have stayed positive about Crossroads House. It was Vivienne’s behaviour that Bess found hard to excuse.

Their hostess had barely asked Bess a single thing. She was too busy questioning Margaret and listening intently to her replies as if preparing to write Margaret’s biography.

When Margaret described running her own museum, Vivienne clasped her hands, saying, “I knew you would do something distinctive. You were always one to follow your own passions and to hell with everyone else.”

Vivienne raised her perfect eyebrows when Margaret talked about the difficulties of managing staff, suppliers, and visitors. “I can’t image how you did it, Margaret—every single day? I simply can’t bear dealing with people.”

And she waved a dismissive hand when Margaret mentioned leaving the auction house where she had worked in the city. Vivienne declared, “Most people who work in those places are cretins. If they didn’t have the brains to appreciate you, you were right to withdraw.”

Listening to the conversation as she trailed behind, Bess could not help comparing Vivienne’s responses to her own. Back in Port Bannir, she had ticked Margaret off for being too hard on her staff. She had urged Margaret to wait and reflect instead of leaving that auction house in a huff. And the first time they met, Bess had gotten into an argument with Margaret over an antique dildo and told her crossly that her maritime museum was cold, unwelcoming, and dull as dishwater.

Was she, Bess, the negative one here? The idea disturbed her.

On the other hand, she wanted to roll her eyes at Vivienne and say, Come on. You can’t think every single thing Margaret’s done is that damn impressive.

And what about Margaret herself? Her manner was strange. Gone was her usual haughtiness, her sharpness and air of authority. Instead, she seemed awkward, almost baffled, and she kept darting nervous glances at Vivienne as if she could hardly believe this was happening. What was that about?

With an effort, Bess told herself to cheer up and change the subject. Breaking into their conversation, she said, “So, Vivienne, tell us about this house. It must be an amazing place to live.”

“Oh!” Vivienne looked startled, as if she’d forgotten her second visitor. She’d walked ahead of Bess; now she turned to look back. Her hair, held back with a clip, swayed between her shoulder blades in a single gleaming curl. “Well, I suppose it is. Some parts of the estate date back to 1837.”

“Really?” Bess thought about mentioning the poster she had seen in town which claimed that Crossroads House was haunted.

But Vivienne was speaking to Margaret again. “Of course, it needs major repairs. More than we can afford right now.”

“What’s she saying?” Ivy demanded. “Money? You’re not getting my money, missy.”

“I don’t want your money, Ivy.” She never called the older woman Gran or Nanna, Bess noticed.

“What would you know about money?” Ivy said. “Burrowing away in a library all your life like a little mole? Reading books for a living? Ridiculous. Why aren’t you married?”

“I restore and preserve rare volumes at the State Library in Hobart,” Vivienne reminded her.

Ivy just snorted. The job sounded interesting to Bess; under different circumstances, she would have asked Vivienne about it.

“But when Ivy fell ill…” Vivienne continued.

“I’m not going into any bloody nursing home, missy, so you can stick that idea where the sun don’t shine.” Ivy clawed on a side table. “Where are my glasses?”

“You broke them this morning, remember? We’ll get them replaced in the city.” Vivienne said, adding tiredly, “Heaven knows when.”

Then she turned to Margaret, and the energy rushed back into her voice. “You got my message. Perhaps we could talk?”

“Certainly.”

Vivienne hesitated, glancing at Bess. “It’s delicate.”

Are you for real? Bess felt like demanding. She’d had enough of this. She imagined flinging off this frilly pink robe and stomping out of here in her underwear.

Instead, she took three deep breaths and waited for the moment to pass. When it did, she realised she didn’t care. Why was she getting upset? They were only here for the afternoon, and most likely she would never see either of her hostesses again. She trusted Margaret, so what did it matter how anyone else behaved?

“I might take a walk around your garden.” Fresh air would do her good.

As she left, she saw Vivienne lay an imploring hand on Margaret’s arm.

* * *

To say Margaret felt dismayed would be an understatement. If she weren’t so averse to melodrama, she would have said her past had been violated. How could Vivienne Bolt be living like this?

This woman was Vivienne but not Vivienne: a faded negative of the girl from graduation night. She had Vivienne’s ethereal beauty, her sharpness, her sarcastic drawl that seemed to draw you into a private joke against the rest of the world. And like on graduation night, she behaved as if she and Margaret had known each other for years.

But where was her optimism, her ambition? Where was that air of certainty that she could go anywhere and do anything if she deemed it good enough for her? Where was that sense of fun that had radiated from the young Vivienne as they’d strolled down St Kilda Road in a light mist of rain past the well-dressed crowds outside the theatres, with Vivienne expertly pretending to be a noisy American tourist, an expensive callgirl, a Russian spy? And the young Margaret, who rarely laughed at anything, pressed her lips together and shook with suppressed mirth.

What had happened to all of that?

“Sorry to leave you stuck here.” Vivienne nodded around the sitting room as she wheeled Ivy out the door for her nap. “Won’t be long.”

The old woman complained, “Who’s stuck? Why are you here? And who’s that long streak of misery in the black coat?”

Margaret shrugged. She’d been called worse.

Walking around the room, Margaret wrinkled her nose at the smell of damp that air fresheners couldn’t quite cover. She didn’t care for this place. Yes, Margaret liked historical relics, but her passion was for seafaring history with its importance to the rise of the modern world, its stories of peril and desperate endurance, its grim majesty. Scrimshaws carved from whales’ teeth, wheelhouses lashed by briny waters, surgeons’ kits, powder kegs, battered old maps, medals from battles on the high seas. Artefacts that even now seemed to carry a whiff of seaweed, rum, and blood.

Those items made Margaret feel invigorated. Ivy’s fussy ornaments and dark, stuffy rooms had the opposite effect.

Returning, Vivienne asked, “Are they any good? Ivy’s poured so much money into this wretched collection. At the expense of the rest of the house, as you can see. I hope the antiques she chose are actually worth something.”

“I’ve not had a chance to look closely. But I’d say, put together, they would make a nice little nest egg.”

“That’s a relief. Come and see the spare room; there’s more in there.”

Despite the size of the house, Vivienne and Ivy only seemed to use a few rooms. The east wing was shut up completely, Vivienne told her, pending repairs they couldn’t afford.

Vivienne led her upstairs and opened the door to a bedroom at the top. “Ivy bought these years ago.” Margaret looked inside and reeled.

The room was full of dolls. Porcelain dolls with leather bodies and hoop skirts, naked Kewpie dolls with wings, clown dolls with ball-joint bodies and sheepskin hair, World War I soldier dolls, character dolls with faces like real children and blue glass eyes. They were lined up on the bed, the windowsill, the top of the wardrobe. They peeped out of drawers and boxes. Some sat on little swings hung from the ceiling.

“Ivy says there’s ten thousand dollars’ worth.” Vivienne wrinkled her nose. “Repulsive, aren’t they? Come in, though. We won’t be disturbed here.”

“Are you sure? It looks disturbing to me.”

Vivienne shut the door behind them.

“You haven’t told me yet what you’ve been doing these twenty-five years,” Margaret said. How strange that all of their earlier conversation had been about Margaret herself.

“Oh, don’t worry; I haven’t been locked up here for a quarter of a century.” Vivienne sighed. “Although it feels like it some days.”

“When we said goodbye, you were about to head off on a scholarship to Rome.”

“Yes, magical stuff. The blue Italian skies, the ruins, the art, the carbohydrates…” Vivienne shrugged the way she’d done on graduation night as if to say, It’s more amazing than most people could imagine, but it’s nothing special to me.

“And what about after that?” Margaret pressed, still trying to reconcile this Vivienne with her own memories. “You talked about going to Cologne, Seoul, Tokyo…”

“All that and more.” She flashed a crooked smile. “I’ll tell you the full story one day. But for now, my time is dictated by Ivy’s medication regime and dodgy bladder, so I hope you’ll forgive me if we cut to the chase.”

It was dismissive, but Margaret couldn’t blame her. She had looked after dying people; she knew the score. She’d never imagined Vivienne, the ultracool loner, having to do it, though.

“In your message, you said someone had been stealing from Ivy and harassing her carers. And you thought somebody had been inside the house.”

“Yes.” Vivienne hesitated. “Well, perhaps. It’s hard to tell. By the time Ivy called me and I travelled down here, she was already really ill. I’m not sure what might have gone on before I arrived. Even if she remembered, she might refuse to tell me out of sheer bloody-mindedness. Still, I need to do the right thing by her. I know she’s rather an old nightmare, but she’s been on her own too long.”

Intrigued, Margaret said, “A property this far out of town… It’s an interesting choice for a thief. You’ve never noticed strange cars coming and going?”

“No.”

“Do you have visitors? Employees? Carers?”