Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

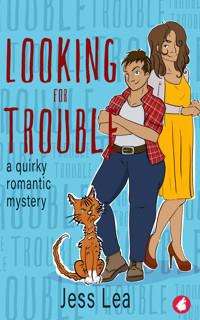

- Herausgeber: Ylva Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

They can't stand each other—until they have to save each other. Nancy is sick of living in the share house from hell, getting dumped by women who aren't that into her, and being stuck in dead-end jobs. It's time to chase her dream to become a political journalist, get her own funky inner-city Melbourne place, and meet Ms Right. Instead, she meets cranky George, a butch, tattooed bus driver and party volunteer who's dodging a vengeful ex-girlfriend. George thinks Nancy is stuck up; Nancy thinks George is the rudest woman she's ever met. The warring pair is caught up in the crazy election campaign of Clara West, a maverick running on the bizarre promise to shut down the internet. Rich, sexy, and dangerous, Clara will stop at nothing in the pursuit of power. Nancy and George must learn to trust each other and act fast if they want to stay alive.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 549

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table Of Contents

Other Books by Jess Lea

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Other Books from Ylva Publishing

About Jess Lea

Sign up for our newsletter to hear

about new and upcoming releases.

www.ylva-publishing.com

Other Books by Jess Lea

A Curious Woman

The Taste of Her – Vol 1 (e-book)

The Taste of Her – Vol 2 (e-book)

The Taste of Her – A Collection of Ten Erotic Short Stories (paperback)

Acknowledgements

Thanks to everyone at Ylva, especially Astrid, Lee, and Miranda. I’m so lucky to get to work with you! Thanks to Rach and Emma for their comments on the early drafts. And thanks especially to my partner Sam for her encouragement, humour, and insights into the strange world of Australian politics. I am truly grateful.

To my family

Chapter 1

Was this what it felt like to be dead?

Nancy clutched her head and squinted in the morning sun. On Northvale’s High Street, the air was murky with traffic fumes and takeaway coffee. A tram clanged past, making her wince. She groaned. I am never turning thirty again.

Students and office workers swarmed past her up the ramp to the railway station, their bumping and jostling making her queasy. What was wrong with her? She’d only gone to a wine bar on a weeknight, eaten seafood pizza at two a.m., then slept on a friend’s couch. That sort of thing had never been a problem before. But this morning her back ached, and her head felt full of gravel. Was she starting to get…old?

She paused to give her change to the woman who sat outside the 7-11, wrapped in a blanket. “Morning, Trudi.”

Trudi gazed up at her through tired eyes. “Are those the clothes you had on yesterday?”

With a sigh, Nancy turned away. If she was getting older, shouldn’t she be growing more dignified too? After all, she was an academic—an intellectual, a professional thinker. Cheer up. Maybe in her fourth decade, everything would get better. Maybe she would evolve into a distinguished, elegant woman, with a French sports car, an all-black wardrobe, and a witty reply to everything.

A kid on a scooter zoomed past, missing her by an inch. She squeaked in alarm and stumbled sideways to avoid a burger squished on the footpath.

Someone dressed as a koala held up a petition for a wildlife charity.

“Sorry, not today,” Nancy said.

“Aw, fark you, ya bourgeois bitch!” yelled a nasal voice from inside the costume. “You don’t care about the koalas at all!”

“I…I do, actually!”

The koala stormed off, lifting a furry middle finger at her.

Okay, so perhaps her new, sophisticated self would emerge tomorrow.

It was only one stop home. She should really walk, but she couldn’t face the exercise. At the entrance to the station, half a dozen people in red T-shirts handed out leaflets. Nancy tried to look past them. Pleasedon’t talk to me.

“G’day there.” The voice sounded older and a little gruff, with a raspy edge that suggested the speaker had once spent a lot of time smoking or shouting. “You look like a woman who knows her own mind. Got a second? There’s a by-election coming up here in Northvale, and we’re representing your Labor candidate, Martin Argyle.”

“I can’t talk now.” Nancy’s mouth felt like sandpaper. “I’m in a hurry.”

“Yeah, I can see that. Try-out for the Olympic team, is it?”

Was this person heckling her? A poor, honest, hungover citizen just trying to get home and shower? Nancy glared at the intruder blocking her path.

She was a solid woman with a greying crewcut, a keychain, and flannelette sleeves rolled up to reveal weathered olive skin and tattoos that looked more truck driver than hipster. With her square shoulders and ramrod-straight stance, she seemed taller than she was.

The woman grinned. “Only kidding. Top night, was it?” She winked. “I bet when you walk into a nightclub, rugby players run out screaming.”

Nancy stared at her. Really? Had things come to this? Not only had she turned thirty without developing an air of mystery or a sparkling wit, but now she couldn’t even catch the train home without some joker harassing her.

The fact that this woman was rather good-looking in a weather-beaten kind of way only made Nancy more annoyed. There was nothing worse than being spoken to rudely by someone you could (hypothetically) think was cute.

“If you must know, some friends took me out for sangria to cheer me up because I’m now indisputably a grown-up—with a PhD, no less—but somehow I’m still working poorly paid tutoring jobs and living in a share-house from hell. And I spent the night on their sofa, which was apparently made of cardboard and fencing wire, meaning I lay awake thinking of all the things I always imagined I’d be doing with my life by now and how I’d be spending it…with a woman who doesn’t annoy me and inspires me to do better.” She took a breath. “So, yes, it was a wonderful night. Thank you for asking.”

Oh dear. Offloading onto strangers wasn’t like her at all. She must be sicker than she thought. Had she hoped this campaigner would feel sorry for her, or get embarrassed and move away?

Instead, the woman laughed. “Well, it sounds like you should vote for our lot, then. We stand for decent wages, affordable housing, and healthcare for everyone—including physio for when sofas attack.” She took a step closer. “Come on, let me convince you.”

Was she for real? Nancy narrowed her eyes. All right, the woman was a little rugged and she had a clean, scrubbed smell about her, like plain soap, which was sort of attractive on the right person. And she had a no-nonsense air that wasn’t totally off-putting. An air of someone used to taking charge.

But Nancy shouldn’t get distracted by that. The woman was a pushy, insensitive pest, stopping her from getting home and lying down.

Nancy summoned a superior tone. “I teach political science at the university. I know why this by-election is happening.”

“Do you?” She hesitated.

“Yes.” Nancy folded her arms. “Because our last MP died. And I know why.”

The woman’s smile faded. Her grip around the flyers tightened.

Nancy had seized the upper hand at last. “Bill O’Brien was the MP here for sixteen years and a member of your party for—what?—thirty years? Until it was recently revealed that he was never eligible to hold office at all, as he wasn’t an Australian citizen. His parents moved here from England when Bill was a baby and forgot to sort out his paperwork. Someone, probably a disgruntled family member, figured out the truth and leaked it to the press. Basically, Bill had been deceiving the public and breaking the law for years.”

“That was an accident! How was he meant to know?” The woman’s shoulders had stiffened, her jaw lifted as if for a fight.

“Still,” Nancy said, “it was a humiliating mistake, and the media had a field day. I wrote an article about it for Australian Political Science.”

“Did you, now?” Her tone rumbled a warning.

“And then Bill O’Brien…passed away.” Nancy faltered, realising too late that she should not have said all that. It was too harsh, too soon. But she couldn’t back out now. “After that fiasco, why should anyone trust your party to run the country?”

“Who are you: a talkback radio host?” Her opponent glared. “It was one mistake. And you’ve got a nerve blaming us for…for what happened to Bill. As if all you professional smartarses who wrote your bloody ‘articles’ about him had nothing to do with it!”

“George…” A girl of about nineteen sidled over. She smiled nervously. “Remember what we talked about in training? We’re here to educate people and build positive rapport with the community…”

“Oh, bugger off, comrade,” George said. “I was door-knocking for the party when you were in your pram.”

“Must be why Australians haven’t voted Labor for years, then,” Nancy said. “I’ve written about that too.” She stepped past them and moved up the ramp to the station platform.

From behind her, the younger woman said, “George, you didn’t even mention Martin—our candidate, remember? We’re meant to talk about his top five personal passion projects. Wait! You can’t chase people! We’re not allowed on the platform.”

George’s motorcycle boots clumped as she caught up with Nancy. “You know, I don’t like your attitude.” She looked Nancy up and down, then sneered. “You latte-sipping types move into these old migrant suburbs, you buy up all the houses, you make us put up with your bike lanes and your wood fires and your late-night cheese bars, and we don’t complain.”

Nancy raised an eyebrow. “I find that hard to believe.”

“But when you insult a decent bloke like Bill and hand our electorate over to the Greens or the Sex Party or some ‘ironic’ candidate dressed as a pirate, well, that’s where I draw the line.”

“Great. Draw it by yourself. My train’s here.”

The screen flashed, announcing the arrival of the 8:05 service. The crossing bells sounded as the train approached. Nancy stepped forward on the crowded platform.

“Have a nice day,” George said sarcastically. “Hope your head’s not sore or anything.”

Scowling, Nancy turned around to reply. A moving weight slammed into her, knocking her forward.

There was a roar and a blast of air as the train shot past. Nancy stumbled, her ankle giving way. She lost her balance and began to topple.

The train was so close: the bright paint, the glinting windows, the gap between the rushing metal giant and the rim of the platform. Wide enough to see down, wide enough to fall down…

“Hey!” Strong hands seized her arm and hauled her backwards. “What the hell?”

She clutched onto her rescuer. The train slowed. Gradually, the world stopped spinning.

“Jesus.” Nancy’s heart pounded as she steadied herself. She glanced up. George. Appalled, she let go.

The train had come to a halt, and people hurried on and off.

George shouted after the culprit, a man on a bicycle who’d hit Nancy in his rush to reach the last carriage. “Watch where you’re going, you clown! You come back here and apologise!”

The man gave them a blank look and loaded his bike into the train.

“Arse-hat,” George muttered. “You okay?”

“Um…yes, I’m quite all right.” Nancy cringed. “Thank you.” Her arm burned where George had grabbed her.

“No worries.” George looked away, shifting her weight from foot to foot, as if equally uncomfortable with how this exchange had turned out.

“Well…I’d better go.” Nancy hurried forward and elbowed her way into the packed carriage.

George stood, frowning, on the platform. She nodded what might have been a goodbye before the doors snapped shut.

* * *

Nancy stood under the shower, one hand braced against the ugly pink tiles with their faded pattern of seashells. The water pelted her shoulders.

I could have died back there.

She told herself to stop being so dramatic. Didn’t everyone nearly fall in front of a train at some point? Still, her knees wobbled. If that awful, rude, stroppy George hadn’t been there…

God, if Nancy had died today, what would she have left behind? A room full of second-hand books and furniture, some students she may or may not have inspired, and a few articles published in academic journals that had a readership of about ten? Even her last conversation had been nothing to be proud of—pontificating about a local by-election and poor dead Bill O’Brien.

Her stomach heaved, last night’s seafood pizza making a bid for freedom. She thrust her face under the water. Snap out of it.

The rattle of the broken ceiling fan and the clanking of the pipes almost drowned out the noise from the terrace houses on either side: the elderly neighbours on the left blasting Greek radio, and the woman on the right shrieking at her toddler, “Madeleine, Mummy doesn’t like it when you take Mummy’s phone! Madeleine, Mummy’s not angry, but you’re not being considerate of me!”

One morning, after listening to an hour of that, Nancy had thumped on the dividing wall and said, “Madeline, for the love of God, give the phone back, and please tell your mother to lower her voice!” She’d regretted it later; there was a complaint made to the landlord about Nancy’s “appalling rudeness.” But those ten minutes of shocked silence had been almost worth it.

She opened her eyes and looked at the ceiling speckled with mould, and the overflowing rubbish bin. A mummified grey sock had lain in the corner of the bathroom since last year. She’d refused to pick it up on principle, believing the culprit would be shamed into doing the right thing eventually. She was still waiting. When Nancy had first moved in here, she’d tried drawing up a cleaning roster. Someone had used it to mop up marinara sauce, then left it balled up in the sink.

If I’d died today, this would have been my last known address.

If she could just get enough saved up, she could make a deposit on a flat of her own. Then she could flee this house and live somewhere quiet and clean. Somewhere she could set up a real study, with a vintage writing desk, Toulouse-Lautrec posters in proper frames, and hundreds of books lining the walls all the way up to the ceiling. Somewhere with a view of flowering gum trees and a clear blue sky. Somewhere she would not find vomit in the umbrella stand or tennis shoes in the freezer.

But even one-bedroom flats were insanely expensive in the inner suburbs of Melbourne. She still had the scraps of her postdoc funding, and she took on freelance research gigs and spent long hours tutoring and marking, but it didn’t pay much, and it was taking ages to save up a proper nest egg. Especially with the pressure to spend every spare hour trying to get published so she might become eligible for one of the few permanent academic jobs one day. If she could beat her way through the hordes of other desperate PhDs, of course.

If she was going to get out of this fug and make a success of herself, she would need to develop some different qualities, soon. Maybe something like the killer instinct.

The door flew open.

“Hey!” She clutched at the slimy shower curtain, yanking it all the way to the wall.

“Carry on. Don’t mind me.” Jasmine, one of her housemates, sat down on the toilet.

“I do mind.” Nancy gritted her teeth. “You could have knocked.”

“You know my cystitis flares up when I have a panic attack.” Jasmine raised her voice. “My anxiety gets triggered when people knock on the front door. I think it reminds me of the time when I was eight and my dad got arrested for stealing all those rare plants from the park. You know, the police didn’t even offer us counselling.”

“Really?” Nancy banged her forehead gently against the tiles, then regretted it. Her hangover was really kicking in now. If she’d been feeling less wretched, she would have tried ordering Jasmine out of the room and possibly thrown a bar of soap at her, not that it had worked the last dozen times. It was hard to be assertive with people who didn’t notice or care what you said or did.

Jasmine said, “Plus, Ahmed was playing his stupid doof-doof music at one a.m.”

“Again?” Nancy had gotten used to sleeping with earplugs, but they only took the edge off.

“And when I yelled at him, he was like, ‘Well, I work nights, so this is five p.m. for me.’ I got him back, though. Six a.m., I tried out my new blender.”

Nancy shut her eyes. “Of course you did.”

“Anyway, I wasn’t going to answer the door because it made me so upset, but Joseph went and opened it, so I told the door-knockers what I thought of them. Hey, I didn’t know we had an election coming up. Do you think we’ll get a new prime minister? I don’t like the one we’ve got now. He looks tired, and I don’t think he exercises. I wrote a post about it.” Jasmine’s wellness blog had ten thousand followers, a fact that gave Nancy a small brain bleed every time she thought about it. Damn it, even Jasmine was more successful than her, and if that wasn’t an incentive to fix up her own life, nothing was.

“It’s just a by-election.”

“They gave me this.” Jasmine shoved a flyer beneath the shower curtain.

“Did you just hand me something you were reading on the toilet?” Still, her curiosity was piqued. “This must be the candidate that that George woman was campaigning for.”

“Who?”

“Um, no one.” Nancy was annoyed she’d remembered her name. Okay, George had rescued her, which was rather annoying in itself, but Nancy didn’t have to dwell on it, did she?

Her memory snapped back to that moment. The tight pressure of George’s fingers as she’d gripped Nancy and hauled her back. The way their bodies had slammed together, George’s broad ribcage surging with surprise, her breath against Nancy’s cheek. The sound of her voice ringing all the way down the platform as she shouted at that guy. George was wasted handing out pamphlets. She should have been a sergeant-major. Nancy could picture her in khakis and stompy boots, roaring at someone to drop and give her twenty push-ups.

Inwardly, she slapped herself. What did I just say about not dwelling on it?

She studied the flyer. The man on the front had a neat grey beard and twinkling eyes behind little round tortoiseshell glasses. He smiled benignly, standing in front of a happy, multicultural crowd of mostly young people. The slogan read, One Big Family.

She frowned. “Martin Argyle… Hey, I remember him.”

“I think that kimchi in the fridge might have gone off,” Jasmine said. “You can have it if you want. It was aggravating my reflux.”

“Martin used to be a lecturer at my uni.” She turned the water off. “He was a professor of environmental justice and really popular. You know, a cool older guy with a grey ponytail and an earring who talked about polar bears and said ‘shit’ in his lectures. He used to have all these starry-eyed students following him around.”

“So do I have to vote in this by-election?”

“If you’re recorded on the electoral roll as living at this address, then yes, it’s compulsory.” Nancy tried holding the clammy shower curtain in front of her without letting it touch her body while reaching for her towel and gripping the flyer between two fingers.

“That’s totally unfair! What if I don’t agree with any of the people who are running? They don’t speak for me.”

“Then you pick the candidate you hate the least.” Nancy wrapped her towel around herself. It felt damp. Had someone else used it? I have gotto get out of here.

“I saw an article on my feed that said most young people don’t identify with democracy anymore,” Jasmine said. “So it’s not very democratic that they still make us do it.”

Was it worth arguing about that? Nancy would rather escape. Clutching her towel, she clambered out of the bathtub, snatched up her clothes, and opened the door with her elbow.

Jasmine said, “But what if these candidates are all really evil or something? What if they’re, like, murderers?”

Nancy rolled her eyes and scuttled away to put some clothes on.

* * *

It wasn’t hard to get things done properly. All you needed was a good system and a bit of elbow grease.

After a morning’s campaigning, George could pack things up in less than a minute. Sandwich boards snapped shut and shoved under one arm; flyers stacked and secured with a rubber band. All items wrapped in plastic to avoid damage, then loaded into the boot of her car, which she’d parked in her secret ticket-free space behind the railway station. A quick tally of how many flyers people had taken and a note made of any feedback or “incidents,” although she might leave out what happened this morning. Her campaign T-shirt removed and folded neatly, just in case she got in a car crash on the way home. Not that it would happen, mind you; she was a top driver, had driven everything from forklift trucks to aged-care buses in her time. She patted her pockets—wallet, keys, phone—and bingo, she was done for the morning. While the kids she had to campaign with dithered around and posed for pictures.

She’d tried telling them how they could get organised and stop wasting time, but they’d looked at her like she was interfering.

Usually she felt satisfied with how well her system worked, but today she couldn’t concentrate. Her breath came fast, and her palms were sweaty. She wiped them on her jeans.

Our last MP died. And I know why.

Christ. She slammed the car boot shut. That bloody woman this morning. Bad enough that she’d talked like a snob and dressed like a scruffy student—George’s two least favourite types of people—but she had to shoot her mouth off about poor old Bill too?

George rubbed some mud off her bumper bar and tried to distract herself with all the things she should have said to that woman:

“You dozy idiot, can’t you watch where you’re going? You’re so damn clever because you went to uni-bloody-versity, but you don’t know how to stand on a platform? Do they not hand out degrees in that? You think I’ve got nothing better to do than scrape you off the tracks and chase down some lycra-loving wanker on a bike? And don’t get me started on them, they’re a bloody menace…”

But it wasn’t like her to yell at someone on the campaign trail. She’d worked plenty of elections before, dealt with plenty of hecklers and yobbos and slack-jawed numpties who couldn’t have named the prime minister for a million bucks. Why had she been so worked up by this woman?

The woman had seemed bright enough in a snotty sort of way. Like she watched the news and maybe even bought the actual newspapers. Sometimes George felt like the last person in the world who still did that. The woman had crazy-curly hair in a shade of chestnut brown, a heart-shaped face, and the sort of pale skin that was freckled all over. Unpierced ears and big, thick librarian glasses. Her hazel eyes had grown wide when she fell.

George remembered that moment of panic, the way everything had slowed as she bolted forward, snatched the woman and dragged her backwards and out of danger. She had felt the heat of the woman’s body through her thin shirt and noticed the smell of her. Coconut mixed with citrus, like a summer dessert.

Not that George went around sniffing strange women. Not that she had any bloody interest in any women right now.

After the last time around? After the last woman, who’d turned out to be not just toxic but actually dangerous? She would have to be off her rocker to go there again. George might not be anyone’s idea of an intellectual, but she liked to think she was smart enough to learn from her mistakes.

“Actually, I teach political science at the university,”she repeated mockingly under her breath. She looked around at her fellow campaigners, most of them university students. “Can I blame you for this lot, then?”

The campaigners were gathering together now, as Tyson, their organiser, said, “All right, beautiful people, let’s bring it in!” He clapped his hands, summoning them for what he called a “turbo meet.”

George knew this would involve everyone sharing one “takeaway learning experience” from today and offering one piece of constructive advice to another person. Last time, George had been reprimanded for talking about eighties prime minister, Bob Hawke (too long ago; younger voters wouldn’t know him), for asking one woman whether she was a union member (too judgemental about people’s choices), and for calling people “sir” and “madam” (too gender-binary). After the discussion, all the volunteers would hold up their phones with an emoji to represent in a non-confrontational way how they were feeling right now. Then there would be group hugs. George always left before that part.

By the time she made it over, Tyson had already started his speech. “Today was a four-star day, team. Tomorrow, I want five!”

“His majesty not joining us, then?” George jerked her thumb at a poster of Martin Argyle. She didn’t like candidates who left other people to pound the pavement for them.

Tyson gave her a look. “As I briefed everyone on our WhatsApp channel this morning, George, Martin is busy. He’s giving the keynote address at a conference on gender equality.”

“Is that why he’s got all these young women doing his shit-work for him?” George nodded around the group.

Tyson’s eyebrow ring bulged as he frowned. Maybe she could get it to pop right off his face? God knows, she’d been trying.

“Anyway,” Tyson said, “I wanted us all to take a moment to welcome a new team member. She’s been based in Martin’s office, but she’s eager to get more hands-on experience.” He waved towards a plump young woman with purple nail polish and a matching lock of purple hair falling over her brow. “Guys, this is Rocket.”

The group chorused, “Hi, Rocket!”

George smiled. “Rocket? Like the lettuce?”

The young woman flinched as if George had slapped her. “Like the thing that goes into space!”

“Oh. Sorry.”

“We love and respect everyone’s chosen names here,” Tyson said. “Right, George?”

She shrugged.

“Now, Rocket, why don’t you tell us about what drew you to Martin’s campaign?”

“Because Martin’s the best.” Rocket’s expression grew eager once more. “I met him when I was in a young leaders’ program at school, and he got me an internship in his office. He wants young people to have a proper say.” She punctuated each sentence with a determined nod. “Martin gives you stuff to do—real stuff, interesting stuff—and he sticks around and listens and truly cares about you.” She spoke rapidly, her gaze urgent, as if afraid the group might not take her seriously.

“We totally hear you,” said Ashley, another campaigner, to nods all round. “Martin’s the real deal.”

“And the party?” George prompted. “You’re committed to what we stand for?”

“Oh, yeah, Martin’s got the best values.” Rocket nodded hard.

George frowned. The party still hadn’t rated a mention.

Rocket said, “Martin’s all about love and inclusion, he stands up against hate, and he encourages you to be yourself and tell your story. And, like, I got bullied for years at school and then in my job at the restaurant, and no one took it seriously. They were just like ‘Suck it up, you’re being too sensitive,’ even when people were stealing my stuff and throwing garbage at me and posting awful things about me, saying I should kill myself, and I was having panic attacks, and still no one cared.” Her words tumbled out in a rush and she leaned in closer, until George could smell her minty toothpaste.

George fought the urge to edge away; she had a weird sense of being trapped.

“That was why I got into Martin’s campaign. To stand up against people like that.”

“You thought Australian politics would be a good place to make a stand against bullying?” George’s voice came out too loud and insensitive. It wasn’t the first time. “Sorry. It does sound like you had a rough ride. But if you go out door-knocking for the party, you’ll spend a lot of time getting told to eff off. Sure you can handle that?”

She had definitely said the wrong thing. Rocket’s hands trembled. George was startled to see tears in her eyes.

“Don’t take any notice of her, Rocket.” Ashley threw an arm around her. “You know what boomers are like; they’re emotionally maladjusted because they weren’t taught how to be actual human beings when they were growing up. And they’re totally entitled ’cause they always had everything handed to them.”

“Boomers?” George scowled. “I’m in my forties! And who are you calling entitled? I’ve been working since I was fifteen, you knucklehead!”

But nobody seemed to be listening. The other girls surrounded Rocket with pats and coos of reassurance.

Tyson said through gritted teeth, “George, could we have a quick one-on-one in five?”

“Sorry, I need to be home in ten.” She stomped back to her car, wishing she still smoked.

Was she being too hard on these kids? After all, they were giving up their time to volunteer for the same party as her, and they’d done nothing wrong except use weird words and grow stupid hair. It wasn’t their fault what had happened to Bill. She was the one who’d been his friend, and a fat lot of good she’d done for him. Was she just being a cranky old grump, no better than her own parents?

George sighed as she unlocked her car, climbed in, and slammed the door. Probably. But did these kids have to talk like they’d swallowed a dictionary—a dictionary she’d never even heard of? Did they have to be so wise and righteous and full of feelings? It made her uncomfortable, and it drove her nuts.

She thought back to the woman she’d argued with this morning. What a snob—she’d clearly thought she was smarter than George—but at least she hadn’t backed down or fainted in horror when George had challenged her. At least she’d stood up for herself and shown a bit of spirit.

George almost smiled as she unfastened her large, heavy steering lock. No one else seemed to use those things nowadays; they all preferred state-of-the-art immobilizers or alarms that nobody paid attention to. But her car had never been broken into, had it? And the lock would make a handy weapon if any bastard ever tried to carjack her.

She stowed it under the seat. An old-fashioned blunt instrument, which no one seemed to have any use for these days.

Chapter 2

As Nancy walked to work, she scrolled through her feed. Another old classmate had contacted her on LinkedIn, and his job title sounded way better than hers. Two friends had gotten pregnant and were holding up their pee tests together. And Nancy’s mum was messaging her on Facebook; Nancy suspected she was worried about how her daughter’s life was shaping up.

“So, what is your job again?” Linda had asked, the last time they’d caught up. Then she’d added, “You know, dear, it’s not too late to become a teacher. I heard some of those teaching courses actually prefer the over-thirties. And you don’t know the children would throw spit-balls at you.”

She crossed through the park, her footfalls releasing the scent of fallen eucalyptus leaves and possum droppings. A huge white cockatoo perched on the children’s swing-set, watching her. It lifted its yellow crest and let out a mocking screech.

Exiting, she glanced around at the streets of Northvale. It was one of Melbourne’s oldest neighbourhoods, a ten-minute drive from the city centre. When Nancy was a kid, this part of the city had been smoky, noisy, and a bit rough. The signs had been in Greek, Italian, and Turkish, outside shops that sold sticky cakes, rococo furniture, and huge, spangled wedding dresses. These days, Northvale was still smoky and noisy, but the houses had quadrupled in price and there was a cold press coffee emporium on every corner. Much as she’d resented George’s remarks about “you latte-sipping types,” George hadn’t been wrong.

She reached the library and headed for the study zone. It was crowded down there, the desks scratched and covered in old graffiti, the air smelling of snack food and B.O. When Nancy had first dreamed of being an academic, she’d pictured herself in a book-lined, wood-panelled private study, with a crackling fire, leather armchairs, and a view of lawns and oak trees. Maybe she would have a big, old-fashioned globe of the world, too, and some dinosaur fossils on the mantelpiece…

She ducked as Angelique lobbed a screwed-up piece of paper at a guy playing noisy games on his phone.

“Oy, Sonic the Hedgehog! Shut the fook up!”

The young guy scowled but did as he was told. The students were scared of Ange. With her spiked black hair turning a funky silver at the temples, blue nail polish, and septum piercing, Angelique Singh exuded cool. Her Manchester accent helped too; it gave her the air of someone on a British cop show. Plus, she’d won prizes for her thesis—The Sociology of Computer Science—and been interviewed for a documentary about edgy young researchers shaking up academia. Even the vice-chancellor seemed impressed by Ange, and Nancy doubted she would be trapped here in the study zone for long. But what about Nancy herself? She took her seat.

“This student,” she said, opening an essay, “has misspelled my name, the name of the unit, and the name of the prime minister. In a political science subject!”

Angelique laughed. The two of them had met at a staff party, sniggering over the worst remarks they’d heard from their students. This had led to dinner at an Italian bistro in Carlton, drinks in a funky bar in Fitzroy, and a sleepless night in Angelique’s “ironic” single bed. Ange had said, “You’ve got such a non-traditional look…” Nancy hadn’t been sure what that meant, but she knew she should feel very lucky. Ange was brilliant, ambitious, and witty. If Nancy had listed the qualities she looked for in a girlfriend, Ange would have ticked every box.

And yet… Nancy tried not to dwell on an inconvenient feeling she had sometimes, a feeling that being with Ange didn’t excite her very much at all. Sure they had fun, and Nancy knew most people thought she’d done far better than she deserved. But a secret, ungrateful part of her kept asking: Is this it?

Her phone vibrated with an email. She read it, winced, and pushed her phone across.

Angelique glanced at it. “Oh, babe. That sucks.”

It was a generic message thanking Nancy for her interest in the position of Junior Lecturer but regretting that due to the high volume of applications, she had been unsuccessful.

“The university of Albury-Wodonga. Two hundred kilometres from decent coffee. I thought they would at least give me an interview.”

“Pff, forget it,” said Angelique. “Have you heard? There’s a new research associate job opening up right here. Full time, four years, good pay, your own office, and no teaching.”

Nancy frowned. “That does sound nice.”

“Nice? If you bagged that one, you could move out of that rubbish tip you’re living in, buy a car, save for a down payment on a cute flat…” Ange smiled encouragingly. “I’m totally going for it.”

“Oh. Great.” Nancy tried to smile back but felt her confidence evaporating.

Angelique rose to her feet and jerked her chin towards the stairs that led to the basement. “Hey, I need to talk to you about something.”

Downstairs, in the archival collection, she turned around. The look on her face was embarrassed, apologetic, and pitying.

“Listen, babe, there’s something I’ve gotta tell you…”

Nancy’s shoulders slumped. Somehow, she could not feel surprised. “Okay. Who is she?”

Angelique wriggled in discomfit. “Azure Anderson.”

“‘Azure’?” Nancy wanted to seem cool but didn’t succeed. “You’re in love with a paint sample?”

“You met her last week, remember? She did her doctoral thesis on the impact of reality TV on Gen Y understandings of sexual health.”

Nancy shut her eyes. “Oh, yes. I remember.”

“Babe, we never said we were exclusive.”

“No.” This was true; Ange had never even used the words “girlfriend” or “dating.” Nancy had assumed she found them too passé.

“Anyway, we’ve been hanging out, and she wants to take it to the next level. I never thought I’d be into monogamy, but she just blows my mind, and…”

“Okay.” Nancy summoned up a smile. “I get it. I’m”—she swallowed—“pleased for you.”

“Oh, babe.” Angelique beamed. “Really?”

“Absolutely.” Nancy managed a supportive nod. “If you’ve found happiness—”

“Oh, I totally have!” Ange hugged her. “I knew you’d be cool about this. Thanks, babe, you’re the best!” She planted a kiss on Nancy’s cheek. “See you around, okay?”

“Sure.” Nancy looked at her shoes. She glanced up in time to catch the glint of Ange’s studded belt around her hips as she climbed the stairs, up and away.

* * *

George was opening the garden gate when her phone rang.

“George Karalis.” The gate squeaked, making her frown. She would get some oil and fix it this afternoon. Might give the lavender a prune while she was out here. She couldn’t stand a messy yard.

Her frown deepened as she recognised the voice on the line. It was the receptionist at one of the chauffeur car companies she drove for. The woman sounded anxious as she explained for the fifth time this month that a client had cancelled and George’s services would not be needed.

“This is not convenient. Are you trying to tell me something?”

The woman squeaked a denial, then insisted she had to take another call, and rang off.

George chewed her lip. She had an idea of whose hidden hand was behind all these cancellations; it was just the kind of thing her former boss would have done. Unless she was being paranoid? Hard to say.

The letterbox was full of envelopes: gas bill, water bill, house-insurance due. Her shoulders knotted up; she tried to relax them. She’d never paid a bill late in her life. She’d always worked hard and done all right for herself, but she’d never been able to shake the fear of ending up broke and helpless. Blame her parents, who’d grown up poor, worked two jobs each, and barely knew the meaning of the word “holiday”.

Never mind, she would sort it out. There were other chauffeur companies out there. If she had to go back to driving squawking rich teenage girls to their school formals and holding their hair back while they spewed—well, she’d been there before.

Except she’d left messages for two other car companies yesterday and had not heard back yet.

“George?” Old Mrs Morgan tottered over to the fence. For a woman with two hip replacements, she could move fast. “How are you, love? You look tired.”

“Fine, thanks, Mrs M.”

“Come round later, then. I made cornflake biscuits.” Mrs Morgan beamed. George had made the mistake of praising those horrible things once and had been picking them out of her teeth for five years since. She prided herself on being honest and had no problem telling most people to go jump, but she was genetically programmed to be polite to old ladies.

“That’s kind of you, Mrs M.”

“When you come around, maybe you could change the battery in my smoke alarm, love?”

“Okay—”

“And look inside my roof, will you? I think I’ve got possums again.”

George held back a sigh. “No worries, Mrs M. Why don’t I get my ladder and see to it now?”

“Oh, that’s good of you, love. And I see you have a secret admirer. Do I hear wedding bells?”

“Beg your pardon?” George followed Mrs M’s pointing finger to an object on her doormat: a gigantic yellow floral arrangement tied up with a bow. Bright marigolds, yellow chrysanthemums like powder-puffs, snapdragons bulging with greenish-yellow buds, the dense golden frills of carnations, and canary-coloured roses, their velvety petals swirled up tight.

It must have cost a bomb, but George didn’t like it. And there was no reason for anyone to leave it here. There were no women in her life now, and after her last relationship had turned so ugly, she told herself that was how she wanted it. She’d had relationships go down the gurgler before, but this one had been different. This one had left her spooked.

She reached down warily, as if a snake might come shooting out and clamp onto her wrist, but there was only a white card.

Thanks again for all your work, it read. Things aren’t the same without you. Hope you are enjoying your other jobs?

There were three kisses, neat little crosses in a row. They made George think of triple-X-rated girlie shows or treasure maps where X marks the spot. Or maybe just someone checking boxes on a form.

She felt a creepy shiver. Only one person would be rich and spiteful enough to taunt her like this. A person who didn’t like being dropped, it seemed.

“Who’s it from?” Mrs Morgan asked. “Do tell!”

But George hurried inside, hauling the flowers after her as if they were proof of a crime.

* * *

Nancy leaned against the window of the tram as it trundled through the streets. Was she upset about breaking up with Angelique? Or was she depressed about not feeling more upset? Maybe being with Ange had never really set her world on fire, and maybe Ange had seen her as more of a sidekick than a girlfriend, but surely three months of hanging out with an attractive, clever, popular woman should have meant more to Nancy than this?

I nearly died this morning, and I wasn’t thinking about Ange at all.

Surely by now she should have got her love life sorted or at least have a suitable woman on the horizon? Instead, she’d drifted apart from her previous girlfriend when the girlfriend took a lecturing job in Canada. And the girlfriend before that, a palaeontologist, had left her to go looking for fossilised molluscs in the Galapagos Islands. She’d discovered a new sub-species and a blonde Swedish researcher, and Nancy hadn’t heard from her since. It had all been very civilised. Nancy seemed to specialise in polite breakups.

Sometimes she wondered what it would be like to experience passion—crazy, reckless, come-what-may passion. Would she ever feel that way? Would any woman ever feel that way about her?

She thought back to this morning, to being snatched away from death under that train. It had been a horrible moment, sweaty and sickening. But a thing like that could have made for a romantic story some day, a couples’ story about “how we met.” If only the woman she’d met hadn’t been that bull-in-a-china-shop George, whom Nancy had not liked one bit.

Someone had left a pamphlet on the seat beside her, promoting Martin Argyle’s campaign.

An idea stirred. What if she did apply for this new job at the university? God knows, she wanted it. But she would need to do something special to get the employers’ attention, something to nudge herself to the front ahead of the other candidates. Ahead of Ange.

What about an article covering this by-election? A fiercely contested struggle in a fashionable part of town might make for a good read. And it would show her employers that she, Nancy, was socially aware, up-to-the-second, connected to people who mattered….

She heard the yelling from inside the share-house before she’d got the door unlocked. Jasmine and the new guy—Raj?—were arguing about who had blocked the kitchen sink with lasagne, while their exchange student, Joseph, had made the mistake of sweeping under the couch. When Nancy stepped into the hall, he was waving around a used condom on the end of the broomstick and demanding to know which of “you filthy animals” had left it there.

“Don’t look at me, mate.” Ahmed strolled past wearing nothing but board shorts slung low. “Never use ’em; it’s like going for a surf with your jeans on.” He wandered into the kitchen, cracked open Nancy’s apple juice, and took a swig.

She walked upstairs, shut herself in her bedroom and leaned against the door, picturing the headlines: Northvale Woman Runs Amuck, Massacres Entire Household…

That was it: this morning’s near-miss had been a warning from the universe. She had to change her life now.

She picked up her phone and searched for the details of a magazine called Conspirator. Conspirator was sold in independent bookshops and groovy record stores. It featured articles by the sort of public intellectuals who opened writers’ festivals and made award-winning indie films. Everyone at the university read it.

She began drafting a pitch to the editor: I have a concept for an article, and I think you’re going to like it.

* * *

It was time for a little mayhem.

Clara West closed her silver laptop, slid it into the safe, and locked the door.

She admired the cherry wood plane of her desk. With the computer gone, that gleaming, burnished space would look good in pictures. Like the empty roads in car commercials, it symbolised freedom and possibility. It needed something to warm it up, though. Another potted plant? Or… She rifled in the bottom drawer and found the framed picture of her late husband, which she kept on hand for times like this.

“May as well make yourself useful.”

John had been snapped on his yacht, gleefully holding up a hooked fish. That wretched yacht—the nuisance and expense! The dreary afternoons spent slathering on sunscreen and drinking the esky dry of wine, biting her tongue not to point out that they could have been in Sydney harbour, or Noosa, or Spain. Not to mention his tantrums over maintenance and the politics of that tedious yacht club. She rolled her eyes. Boys and their toys.

Still, John had loved that silly little boat, bless him. Right up until that warm, still night up the coast when a squall had blown up out of nowhere, taking down the yacht and John with it. It was a miracle that Clara had survived with barely a scratch. But she’d always been a light sleeper, while poor John had been dead to the world.

She smiled. Well, everything happened for a reason.

She gave the picture a quick polish, then placed it where it would be more visible to a visiting journalist than to her.

She stood up, pulled at her jacket until it hung straight, then stepped over to the window. From this office, she’d run her successful activewear company and managed the share market ventures and offshore accounts she’d inherited from John. She had doubled their worth in the past year.

Her office afforded a panorama view over the city, past the station yards, the Melbourne Cricket Ground, the Botanical Gardens, and the miles of suburbia stretching all the way to the Dandenong Ranges, a green haze of mountains on the horizon.

That was what success gave you, she decided. A clear view of the bigger picture which most people, tangled up in their daily struggles, never got to see.

Then she looked straight down. Thirty storeys. From here, the cars were like colourful toys, and the people scurried to and fro, seeming tiny and less human from this angle. If you fell from here, you would be unrecognisable when you hit that pavement.

But she had never been afraid of falling.

Chapter 3

A sign hung across the entrance to the town hall, welcoming people to a forum hosted by the student association.The three main candidates for the by-election would be speaking. Nancy stood taller. Your chance starts here. Don’t blow it.

To her surprise, Conspirator magazine had accepted her pitch.

“Can’t believe no one suggested it before,” the editor said.

Now she just had to write it. And make it original, provocative, insightful, the sort of thing that would catch the eye of her prospective employers and move her job application to the top of the pile. She gulped and double-checked that she’d brought her favourite notebook and her lucky pen.

People bustled around the hall, setting up. Above the stage hung a sixty-year-old portrait of Queen Elizabeth, and the walls displayed a collection of nineteenth-century paintings of the Australian bush. She studied them. Lonely human figures dwarfed by gigantic gumtrees, sunlight filtering through the greyish-green scrub and campfire smoke. Straying cattle, bark huts, wallaby traps. And bush graves, and lost children.

“Hey there!” A young woman waved.

Nancy recognised her from the train station. Tonight, she wore a red T-shirt with the slogan One Big Family and little round tortoiseshell glasses, like the pair worn by Martin Argyle on his posters.

“Welcome! I’m Ashley.”

“Nancy.”

“Great to see you!” Ashley’s smile was warm, supportive, and just slightly patronising, as if she found it remarkable that someone over twenty-five had managed to leave the house for the evening. “What made you decide to come?”

“Well…” Nancy ordered herself to sound confident. “I’m writing an article about the by-election for Conspirator magazine.”

“Wow, you write for them?” Ashley’s tone was perplexed, like she was struggling to match Conspirator’s funky brand with the woman standing in front of her. Nancy wondered what the problem was. Her age? Her haircut? Or just the faint air of dorkiness that she suspected always clung to her?

“Nice glasses.”

“Oh.” Ashley giggled. “I needed a new set, and some of us thought it would be fun to surprise Martin. He doesn’t mind it when we prank him; he’s really down-to-earth, even though he’s so brilliant.”

The organisers were doing well; they’d even got the sound system functioning with scarcely a screech. One woman directed operations. Simultaneously, it seemed, she managed to install the accessibility ramp to the stage, chat with the Aboriginal elder who’d come to deliver the Welcome to Country, and fix the tea urn which wheezed in the corner.

Nancy recognised her. It was George, from the railway station.

Should she speak to her or sneak off? Nancy hesitated. But George saw her. She paused, then lifted her chin in a brusque greeting, as if inviting Nancy closer.

Curious, Nancy sidled across. “You look busy tonight.”

“Well.” George sounded stiff. “It keeps me off the streets.” She rocked on the balls of her feet. “You all right after that tumble yesterday?”

“Fine, thank you.” This was all the more uncomfortable because, secretly, Nancy had always had a bit of a thing for butch older women. Ever since her totally unrequited crush on Ms Todd, her Year 9 P.E. teacher. That was the only time in her life Nancy had tried to develop an interest in soccer.

She said, “I thought the student association was running this event. Are you a mature-aged student?”

George snorted. “Hell, no. I don’t think universities let the likes of me in. But the association’s full of young party members, and they need all the help they can get.” She paused, her breathing easy beneath her ironed, button-down shirt. It fitted her well, as if she might have had it made for her. “We didn’t meet properly yesterday. I’m George Karalis.”

“Nancy Rowden.”

George’s handshake was firm, her nails short and smooth. There was a swordfish tattooed on her forearm and an old leather-and-steel bracelet around her wrist. It was frayed but spotlessly clean. Nancy imagined running her finger along it, then wondered why she had just imagined that.

She said, “I’m surprised there’s no acknowledgement here of Bill O’Brien. You know, the, um, late MP.”

George’s mouth tightened. “Yeah. I’ve—I’ve been trying to sort that.”

“I didn’t mean to criticise you.”

George shook her head, signalling she’d rather change the subject. Why did the topic of Bill O’Brien seem so sensitive to her?

Nancy said, “I’m writing about the by-election for Conspirator magazine.”

“Is that right?”

“I thought I’d try and speak with some of Martin Argyle’s volunteers. Maybe I could interview you too? You know, for a…different perspective.”

“A grumpy old perspective, you mean?” George almost smiled. “I’m here for the party, not the candidate. Be careful interviewing me. I speak my mind.”

Nancy held back a smirk. “Gosh, you don’t say?”

George’s tone changed, growing more thoughtful. “Hey, I found that other article you wrote. About Bill O’Brien.”

“Really?” Nancy was surprised by the thought of George reading an academic journal. She seemed like the sort of person who would think that was a waste of time. Deep down, Nancy had assumed most of her readers were colleagues at the university who probably only read her stuff in the hope of finding a mistake and pointing it out to her. “You subscribe to Australian Political Science?”

“Oh, yeah. I don’t even buy my groceries till I’ve forked out for that thing.” George rolled her eyes. “I can use a library, you know.”

“I wasn’t implying—”

“Imply what you want. I don’t care.” George narrowed her eyes. “You’re not a bad writer.” It sounded more like a provocation than a compliment. “If you’d cut out all the ‘semiotics’ and ‘hegemony’ stuff, it might have been an okay read.”

“How generous of you.” Nancy eyed her warily.

“Pity you can’t make up your mind about things.”

“Excuse me?”

“Well.” George rolled her shoulders as if limbering up for a struggle.

Nancy got the sense she’d been mulling this criticism over for a while, whatever it was going to be.

“You wrote about how people treated Bill when he was kicked out of office. The media harassment, the threats, the voters who said he’d betrayed them, the colleagues who cut him loose…”

“That’s right.” Nancy winced. “Of course, I wrote that article before he—before he died.”

“Yeah, but you never came out and said what you really thought about what happened. Your article was all ‘moreover’ and ‘notwithstanding,’ yada yada. But you didn’t say what should have happened instead.” Her brow furrowed. “You didn’t say whether there was anything people could have done to fix things.”

“Well…” Panic seized her. God, was that true? Was her writing really bland and indecisive? Would her employers think so, too?

Her voice came out defensive as she said, “Listen, journal articles have to be written with a certain sophistication. Detachment. You have to look at the nuances, the complexities…”

“And I’m too thick to understand that, am I?” George scowled.

“No—”

“Oh, forget it.”

And George had stalked away before Nancy could ask what her problem was now.

Then a voice called from the doorway, “Is this a private party, or can anyone crash?” Martin Argyle had arrived.

Excitement rippled through the crowd, and people hurried over. Martin was flanked by a woman with bright red hair who held his coat and papers, and a man with an eyebrow ring, who waved some people closer and shooed others away.

“Sorry to have kept you all.” Martin seemed to be speaking normally, but somehow his jovial voice carried right across the hall. “We found a distressed rainbow lorikeet in my garden, so we had to take it to a bird shelter.”

There were nods of approval. Then there came a blast of music; apparently several people had cued it on their phones. A dozen students stepped out of the crowd, all wearing red T-shirts emblazoned with One Big Family. Grinning, they assumed zany poses.

Really?Had flash mobs become cool again? Nancy grabbed her phone, sensing this would be worth photographing.

Toni Basil’s “Mickey” blared out and the young volunteers launched into a dance routine, complete with claps, high-kicks, body rolls, and even a somersault. They sang along breathlessly, replacing the name “Mickey” with “Marty.” Thankfully, someone had cut out the saucier lyrics.

Martin Argyle doubled over with laughter. He clapped. “You got me! Bravo!”

He gave every impression that this was a spontaneous prank, a surprise to him too. But Nancy looked over to where the Green and Liberal candidates stood abandoned. If Martin had thrown cream pies in their faces, they could not have looked more furious.

The song ended with cheers, giggles, and hugs. Martin Argyle had his arm around a chubby young woman with a tuft of purple hair, apparently asking her to teach him the sideways-shimmy move.

The man with the eyebrow ring caught Nancy staring. “Hey, I hope we’re not too crazy for you! But old-fashioned politicians aren’t allowed around here!”

She smiled politely, feeling a little stunned. When she looked behind her, George had vanished into the crowd.

* * *

“You’re a treasure, Glenn.”

Clara West hung up her phone with a satisfied smile and looked out her windscreen into the darkened carpark. It was empty now. Somewhere nearby, water dripped onto the concrete.

Numbers: that was all an election boiled down to. Funny, back at school, she’d never been much good at maths. Hard to see the point, then. But numbers: percentages, growth rates, the probability of one result or another…over her years in business, she had come to enjoy all that.

She’d come to enjoy gambling, too, perhaps more than she should. Still, she never risked what she couldn’t afford to lose.

The clock glowed on her dashboard. She would have to get moving if she wanted to make this funny little forum. It should be entertaining in its own way.

But there was something she needed to do first. She opened the photos folder on her phone and looked at the picture that beamed back at her. Her face twitched with something like emotion. When the picture was taken, she’d fancied herself in love.

Then she hit “delete”, erasing the happy snap. She did the same to the next photo and the next, one memory after another vanishing in an instant.

No digital record was private nowadays and in cyberspace anyone was fair game. She’d learned that the hard way when there had been attempts to hack her finances and email accounts. It was as if people thought they would find something disreputable there, which was just insulting. And she’d heard of the sorts of things that went on via the dark web. You could find people there to commit murder for you, supposedly, although she couldn’t understand why anyone would do it that way. What had happened to relationships, to trust?

Anyway, the World Wide Web made her uneasy. She didn’t care for the thought that there were people out there who knew things she didn’t and did things she couldn’t control.

She shook off the thought of losing those photos. Of course, she had secured one or two under very firm lock and key in case she needed future…leverage. Well, you never knew. But there was no reason to carry them around in her pocket, for heaven’s sake.

Who needed the past? Souvenirs, regrets, happy times now conspicuous by their absence? Not her. She might have one or two faults, but no one had ever accused her of being sentimental. Love had turned out to be as unreliable and absurd as she’d always suspected it would be, and she had dealt with it accordingly.

Some soldiers went into battle with photographs of their loved ones tucked against their hearts. But Clara had always fought best and most ruthlessly when she was alone.

* * *

“This is bullshit.” George grabbed the long spoon from the punch bowl and prodded Tyson in the back with it. She couldn’t reach Argyle himself; he was surrounded by admirers, too busy slapping backs and posing for pictures.

She snapped at Tyson, “Got a second, maestro? I need a word with the boss.”

“Not now, George.” He had recovered his composure and smiled left and right, aware of all the photographs being taken nearby. “Martin’s busy.”

“Doing what? Judging So You Think You Can Dance?” George moved sideways, stopping him. “I said I want a word.”

He made a show of sighing reluctantly. “All right, George. What is it this time?”