Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

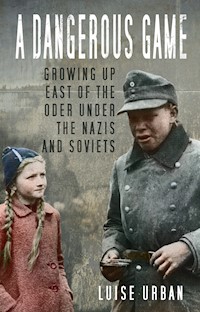

Luise Urban was born in 1933 into a world about to be turned upside down. Her family lived east of the river Oder. Fatefully, her family were not Nazi Party members and suffered as a result. As the Third Reich crumbled and the Red Army advanced, she was one of 15 million Germans trapped in a war zone during the terrible winter of 1945. Weakened by starvation and forced to flee their home, it was only the bravery of Luise's mother that saved the family from total destruction. The Oder–Neisse line (Oder-Neiße-Grenze) is the German–Polish border drawn in the aftermath of the war. The line primarily follows the Oder and Neisse rivers to the Baltic Sea west of the city of Stettin. All pre-war German territory east of the line and within the 1937 German boundaries was discussed at the Potsdam Conference in 1945. Germany was to lose 25 per cent of her territory under the agreement. Crucially, Stalin, Churchill and Truman also agreed to the expulsion of the German population beyond the new eastern borders. This meant that almost all of the native German population was killed, fled or was driven out by force. In A Dangerous Game, Luise relives that harrowing time, written in memory of her mother, to whom she owes her life. It is the story of a child, but it is not a story for children.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 405

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Meiner gütigen Mutter mit den klugen Augen.To my loving mother with eyes full of wisdom.

‘One day, early in February, I went outside to play in the yard. I had a little boy with me who was about six years old, he was the son of refugees staying with us. We were bombarding a tree with snowballs to see who could achieve the most hits. It was fun. A Russian soldier appeared in the driveway leading to our yard and took pot shots at us. Little Richard fell down in the snow, dead … I walked back into the house and said, “They have shot little Richard”.’

The author and publishers would like to thank Clare Agnew for all her help in the creation of this book.

The opinions expressed in this work are those of the author and in no way reflect the attitudes or beliefs of The History Press and its associated subsidiaries.

First published 2013

This paperback edition published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Luise Urban, 2013, 2022

The right of Luise Urban to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7524 9423 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Introduction

Foreword

The Wrong Side of a River

School

Things Go Wrong

Food, Always Food

Bidding Farewell to Grandfather

Mother Courage

Raus! Uhodi!

Home

Burying the Dead

The Scent of Lilac

The Order to Go West

West of the Oder

Our New Socialist Friends

To the Border

Climbing out of a Dark Hole

To England

About the Author

Introduction

It is not necessary to understand the military and political background to this story. As Luise Urban says herself, she has not delved into the historical record or attempted to verify facts. She has simply set down her own childhood memories of a horribly cruel period in history. Her experience, the sufferings of her own family and the torment of all those civilians (not to exclude the soldiers and POWs) east of the Oder are described with a terrible clarity. Some readers, however, may find these brief notes of use. Why, for example, is the Oder the defining border of misery? Why did the Russians treat Polish POWs and refugees with such appalling brutality?

Before the Second World War, Germany’s eastern border with Poland had been fixed at the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. Certain adjustments were made to the line to allow for the ethnic composition of small areas beyond the traditional provincial borders. Inevitably, some people were left, or felt they had been left, on ‘the wrong side of the line’. Upper Silesia and Pomeralia (eastern Pomerania) were divided, leaving areas populated by Poles as well as other Slavic minorities on the German side and Germans on the Polish side. A further complication was that the border cut Germany in two: the so-called Polish Corridor and the ‘Free City’ of Danzig, established to provide Poland with access to the Baltic Sea, were populated predominantly by Germans. History shows that when lines are drawn on a map and nations or countries are not ‘naturally’ defined over time by geographical features such as mountain ranges or rivers, tension or disaster often follows, from the Balkans to the Indian subcontinent, from Iraq to several modern African states such as Nigeria, where ethnic enmities led to the tragedy of the short-lived state of Biafra.

The Oder–Neisse line (Oder-Neiße-Grenze) is the German-Polish border drawn in the aftermath of the Second World War. The line primarily follows the Oder and Neisse rivers to the Baltic Sea west of the city of Stettin. Hence Winston Churchill’s memorable and prophetic judgement of 5 May 1946: ‘From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.’ All pre-war German territory east of the line and within the 1937 German boundaries was discussed at the Potsdam Conference (July–August 1945). Germany was to lose 25% of her territory under the agreement. Crucially, some might say (including most certainly Luise Urban) callously, the ‘Big Three’– Stalin, Churchill and Truman – also agreed to the expulsion of the German population beyond the new eastern borders. This meant that almost all of the native German population was killed, fled or was driven out. The Oder–Neisse line would divide the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) and Poland from 1950 to 1990. East Germany confirmed the border with Poland in 1950. West Germany only officially accepted it in 1970. In 1990 the reunified Germany signed a treaty with Poland recognising it as their border.

The Third Reich’s last battle is usually identified as that for Berlin, a doomed last effort with the Führer directing it from his bunker. It can be argued, however, that the last concerted battle was actually directed by Generaloberst Gotthard Heinrici. He took command of Army Group Vistula (Heeresgruppe Weichsel) on 20 March 1945, before the enormous Soviet thrust towards Berlin was launched in April. Heinrici, not Hitler, decided that there was only one strategic course left for Germany: to hold the Soviets back along the Oder Front long enough for the western Allies to cross the Elbe River. The war was lost and Heinrici accepted it. All that was left was to bring the western Allies as far as possible east to save as many as possible of the German population from the fearsome revenge that would overtake them at the hands of the Soviets. Defending the Oder Front might force General Eisenhower to order his armies into the planned postwar Soviet Zone of Occupation, as outlined in the top secret western Allies’ plan, Eclipse, which was designed to prevent the Soviets from ‘overstepping the mark’ westward – into Denmark specifically – and gaining the access to the Atlantic she offered. Berlin, Heinrici ordered, would not be defended. OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, Supreme Command of the Armed Forces) decided on 23 April to defend the capital. This left Heinrici at odds with OKW over operations along the Oder Front. His defence against the Soviets was undermined. On 28 April, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel discovered troops under Heinrici’s command marching away from Berlin against the Führer’s orders. A furious Keitel tracked down Heinrici and accused him of treason and cowardice. Heinrici was relieved of his command the next day, as an endless procession of wounded and disarmed soldiers and refugees streamed past, fleeing from the Soviets.

This summary of events in 1945 east of the Oder tends to construct an inadequate or misleading ‘net’ of cause and effect to throw over the chaos that led to the deaths of millions of innocent people, including most members of Luise Urban’s family.

Foreword

I am living far away from the place of my birth and home to me is now a place where I have been asked constantly: ‘What are you doing here? Where do you come from?’ So, I will tell my story. Not because I think I am a gifted writer and the world should know about it. No, but because it is only reasonable to explain to my children where I come from and why I am here.

This is the story of my childhood. Sadly, it is not suitable to be read by children.

I am German, but have written this in English. To recall the past in German is far too painful and I could not, remotely, tolerate it. In addition, my extensive knowledge of German vocabulary and therefore better choice of words would make it impossible for me to pass on accurately the trauma I suffered as a child. To relive past events in English is the distancing mechanism I need to recount my early life. Writing in English means I can safely sit in a glasshouse and look out, or rather back, as what I am about to relate cannot hurt me any more. There is a barrier between me and the world I am describing. That world is crystal clear and I can give an almost detached account of it. It is with great sorrow that I must insist I am writing about events that truly took place.

You may throw as many stones as you like at my glasshouse. It will not break. I am indestructible.

The Wrong Side of a River

I was born on the wrong side of a river at the wrong time in history. The times I am writing about are the Hitler years and the immediate post-war years. It was a tragic time for the world and I had the misfortune of being born on the eastern side of that big river, the Oder.

My family was well-to-do with a sizeable property and a large house, which could not only accommodate four generations of one family but also one of my uncles with his family and a separate flat for a very kind, very old lady who had helped to bring up my father. When he got married she wished to live in his house so that she could be with her little Johnny.

I know little about the wide-ranging backgrounds of close members of my family, as all records were destroyed during the war. Out of 26 of us who lived in the house, only 9 survived 1945; and then there was no one left to ask. I know that my maternal grandfather was the descendant of an Italian rebel who had to flee Italy after the Garibaldi uprising. He settled somewhere in Slovakia and my grandfather stems from that lineage. He spoke German and Slavonic, which was his first language. He was a very stern, principled man with a keen interest in astronomy and the humanities and he was one of the few people that I know who could recite Goethe’s Faust from beginning to end by heart.

My great-grandfather on my mother’s side was very special too. His rooms were full of books and beautiful china, which he collected. When the day’s work was done, he used to read and read and read. He had a lovable weakness: he adored cooking for me, his eldest great-grandchild. Needless to say, I was happy to hang around in his rooms for the glorious food, with books and newspapers stacked high on the table.

No one taught me to read but with my great-grandfather reading aloud to me at times from newspapers I was able to make sense of the large, printed squiggles. It was hard though, because the print was the highly ornamental old gothic German print. But I cracked it without help. No one in my family took any notice of my ability to read at a very young age; apparently everyone in my immediate family could read long before school age. It was accepted as normal. Breathing, eating, drinking, reading – that’s what children did.

Sometimes my great-grandfather would speak to me in a strange language; it probably sounded like Dutch. He was actually descended from Dutch dam builders whom Frederick the Great had attracted to live and work in Prussia. They were expert dam builders and the Oder needed damming up with extensive earthworks, up to 30m thick in places. They lasted until they were destroyed in 1945. As a result of many years of neglect thereafter there were catastrophic consequences for the area.

I much later discovered that the language in which my great-grandfather spoke to me was not really Dutch but resembled closely the old Gothic, which was classed as a dead language no longer spoken and understood. It had clearly travelled from the south down the Rhine, pockets had survived and then, under Frederick the Great, it had come to the east of the Oder with the dam builders.

I had as a grown-up no difficulties reading the Hildebrand, the Hildebrandslied Saga in Old High German. The language diversity in my family was accentuated by my great-grandfather’s wife, great-grandmama Gauthier. She was from French aristocratic stock. Her family survived Bartholomaeus Night (the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572). During the night of 23/24 August many leaders of the French protestants – Huguenots – were assassinated, apparently on the orders of the Queen Mother, Catherine de’ Medici, and many more Protestants were murdered by the mob. Great-grandmama’s family escaped and fled to Prussia. Their descendants lived under the protection of Frederick the Great. Most of them settled in Berlin, but my great-grandmother followed her husband to a town east of the Oder and as a token of her love for him accepted German nationality to honour him, the first and only one from all her family to do so. Great-grandmama was a most beautiful woman. In their part of the house you would hear French; in my grandparents’ part you would hear Slavonic. But we all spoke German in public. In the 1930s and 1940s it would have been most unwise to utter foreign sounds, which could have fatal consequences.

I know little about my father’s family, except that they had suffered greatly in the First World War. Two brothers had gone down in U-boats and when my father was five years old his father was crushed by a heavy piece of machinery that had slipped off a railway wagon during unloading at Küstrin. His mother, whose father was Polish, was a very imposing figure – very clever, compassionate, with a heart of gold. She was propertied and although she had many proposals of marriage after she was widowed, she could not bring herself to remarry because no one could ever be as good and kind and caring as her beloved Gustav. She had a very hard time bringing up her children after the Great War, but all her children won scholarships for higher education. We saw nothing of her after 1945 as she managed to escape to East Berlin.

Much later, after my father had been released as a POW to the West of Germany, he asked the German Democratic Republic (GDR) authorities for permission to visit her because she had become very ill. Permission was refused. When a telegram arrived to say she had died, he was refused permission to attend her funeral. The reason: there was no point in travelling to Berlin now, as she was dead.

The same happened to my mother in 1983. Her father, my beloved grandfather, died in the GDR. But we lived in West Germany. Permission to attend his funeral was not granted. He was dead. So, why do you want to come to the GDR? To explain: in the early days of the GDR only visits from parents to children were allowed, or children to parents. The rules were relaxed later on. But the paperwork that went with these visits was formidable; every visitor was treated as a potential spy. You had to present yourself at the police station within one hour of arrival, you had to attend ‘enlightenment classes’, which you did with great enthusiasm – and it was, of course, a great joy for you to bring your relatives as well. Even if you learned nothing, at least the police knew where you were in the evenings. And your relatives better attend these classes as well because if they didn’t, they would disappear after you had travelled home, never to be heard of again.

It was virtually impossible to assist our East German relatives in any way. On one occasion my mother took several pairs of tights with her for her sister-in-law. On her way back to the West she was stopped by the GDR police and questioned about the now missing tights. My mother told them that she had thrown them away as they were laddered. ‘Next time,’ said the friendly policeman, ‘bring them back with you.’ Point taken. The GDR was leading the world – I have forgotten what in – they needed no assistance with anything and certainly no handouts.

So theoretically you could visit your East German relatives, but the East had exclusion zones, up to 15km and even up to 30km east of the river Elbe, which was the border with the West. And with great foresight old people’s homes were opened in those exclusion zones, so that no western spies could infiltrate the minds of the elderly. The regime worked hard to keep them sheltered and safe.

We had been robbed of all our earthly possessions, everything that previous generations had built up was gone. Far worse: most of our much loved immediate family had been cruelly killed in 1945. Now political dogma robbed us of even saying farewell to our remaining nearest and dearest.

I am writing all this from memory. I have not consulted historical records or anything that might help me to reconstruct the events of late 1944 to 1946 and a few years thereafter. I am truthfully recording what I saw and heard and lived through. I saw, obviously, through the eyes of a child and with a child’s mind, but I do have a good memory and my observations are historically correct. This is not fiction. This is the truth unfolding.

Although I was very young, a baby really, some events are crystal clear in my mind.

It must have been autumn judging by the colour of the leaves on the trees. My parents had arranged to meet somewhere in the afternoon and I was taken there in the pram by my mother. It must have been a special occasion for my parents, as they talked about it years later. I was overjoyed when I interrupted them and enthusiastically shouted, ‘Yes, I remember the place!’ and they said, you can’t, you were barely one year old and you were in a pram. And I continued delightedly, yes, and the pram was brown and cream and there was a small open travelling circus in a clearing; I described to them a scantily dressed young acrobat performing as a contortionist, announced and given a running commentary by an older compere dressed formally in a black suit. And lots of people laughed and shouted and clapped their hands. My parents looked at me at first in disbelief, but I was their first-born and naturally the most beautiful and cleverest girl in the world. So, if ‘Prinzeβchen’ said it was like so, then it must have been like so and both parents claimed: ‘She takes after me.’

I remember another occasion when I was given my first pair of ankle-high shoes. Children in those days wore high lace-up boots, which made for very weak ankle joints. No one seemed to have realised this. But I walked very early and so well that I was treated to grown up shoes. I walked into the yard which was very large. I walked into the orchard which was even larger. And as you might expect, my feet got tired from the unusual exercise and I twisted my left ankle. I was hurt, I fell and I could not get up. But I did not cry. So sure and aware was I of the security of my home and the loving care of my parents that I only had to sit there where I was, I would be rescued. And indeed, a little later my father came running towards me with arms outstretched, I was picked up and kissed and made a fuss of, a doctor was called, I was bandaged up and spoiled and given a lot of presents the next day – more plasticine, drawing paper, coloured pencils – there was no end to all the goodies and visitors and uncles and aunts with still more presents. I rather liked being injured, but when that was over I was back to high lace-up boots. That was when I was about 16 months old.

Another heartwarming image springs to mind. I remember with great affection sitting on a sand-coloured blanket on the fresh green grass in the garden under a large apple tree covered with pinkish-white blossoms, the sweet scent of them, the buzzing of bumble bees, the jubilant birds, the blue sky, the golden sun, the warm, soft air and the bright yellow dandelions dotted all around me. I see myself laughing and being consciously aware of the joy and beauty of spring; the month must have been May, so I was around 18 months old.

Children were royalty in our household, we were the most important people in the lives of our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents, but our upbringing was what one might call old-fashioned. I call it very strict and what we could do or not do was clearly defined. We could do no wrong. Meaning not outright wrong, better phrased as perhaps not quite right, but never wrong. There was plenty of room for talking and explaining.

Once I was frustrated and as I did not quite understand what was required of me I spoke up and said, ‘I cannot help it, I don’t yet have the reasoning of a grown-up.’ This was quite calmly accepted as a perfectly plausible explanation for my behaviour and my status was almost that of another grown-up engaged in a conversation among equals.

Great-grandmama Gauthier was the grande dame in our family. She was an exceedingly beautiful woman. Her whole demeanour commanded respect. She used to sit on a dais by the window from which she could overlook the entire yard and outbuildings arranged in a rectangle, with the house forming one of the sides. From that window she would supervise the comings and goings of everyone, people and animals alike. You could not reach the front door from the street or from the front field without first having to walk through the yard and you could not come from the fields at the back of the house without walking through the orchard and then through the yard. People always greeted her most respectfully and she ever so slightly bowed her head in acknowledgement.

You were not allowed to call her nana or granny or something that familiar. She was addressed very formally as great-grandmama, followed by her maiden surname. When afternoon came I was allowed to visit her accompanied by my mother. Such a visit was a great honour and was quite a performance. I was washed and combed and polished until I shone, best dress was to be worn, always designed and hand sewn by my father’s mother, who was very fashion conscious. We would walk up to her room and knock. We were expected, of course, to be punctual. We were asked in and remained standing at a respectable distance from her dais, my mother within touching distance behind me. Upon a slight push from my mother in my back I would curtsy and wish her ‘Good afternoon, Great-grandmama Gauthier.’ Then she would say, ‘Good afternoon, mein liebes Kind, have you had a good day?’ I would curtsy again and say ‘Yes, thank you Great-grandmama Gauthier.’ Then ‘Mein liebes Kind, what have you learnt today?’ Upon that I got another push in my back from my mother, took another step forward, curtsied again and recited a verse. A four-liner as a rule. Then she thanked me and wished me good night. ‘Schlaf schön und träume süβ’ (‘sleep well and sweet dreams’). Another curtsy and a thank-you and with that we were dismissed.

My mother never had to suffer the shame of me forgetting my words. Their delivery was practised again and again. While I had my dinner, my mother would sit opposite me at the table with a book, Verses for Young Children. She would read some out to me and then we would choose one suitable to be recited in the afternoon. How to curtsy and when to curtsy was also well practised before my early afternoon rest. After all, I was under two years old – but nonetheless well trained for an audience with Great-grandmama Gauthier.

Then there came a day when the house fell silent. There was great sorrow, a lot of people dressed in black arrived, uncles, aunties, people I had never seen before, all in black, some crying. They carried huge bouquets and wreaths in green and white, some had small persons with them, small like me and like me dressed all in white. They were called cousins. That was news to me. I had not known that I was a cousin. It was so exciting. I wandered out of the house and there, like an apparition from a fairy tale, a most beautiful carriage drew up in front of the house, its polished black wood and shining glass sparkling in the bright sunlight. It was drawn by four black horses, the finest I had ever seen, decorated like the carriage with silver ornaments and tassels, wearing black and silver crowns on their heads. It was breathtaking. I was overjoyed and started running back to the house to tell my mother about this truly unbelievable, magnificent sight.

But I was held back; some men, including my father, were walking slowly past me carrying on their shoulders a long, black, shiny box decorated with silver ornaments and masses of white flowers. My great-grandfather walked behind them, crying and I remember clearly him saying, ‘I have always held her in the highest esteem.’ I did not know what this meant. It sounded as if his heart was speaking for him.

Great-grandmama Gauthier had died. Our family had lost with her a piece of history, a way of life gone forever and I am grateful that I can remember this glimpse of the past. This took place four or five weeks before my second birthday.

After that my grandfather took a great interest in me. The learning of poems continued; there was not a fairy tale I did not know. My grandfather seemed to know all the stories in all the books in all the world. I adored his readings and I placed my foot wherever he took his away.

But life became tough. I had to learn about work. As the future heiress of the property I had to learn all about it: how to look after the land, the animals, the trees, the people, the garden, the fences, and so many more things, not to mention the house itself. I was given my own garden, my own tools. This was not a game. I learnt to graft the cherry tree in my own garden when I was four. But long before even then I was told if ever you ask someone to do a job, know how to do the job yourself. I was instructed to clear a path alongside the house about 12m long; there was a gate at one end. This path was to be cleaned of any bits of straw or whatever should not be there, then raked smooth, showing a proper recognisable pattern, neat and tidy, please. The gate was then to be closed.

The fact that someone later on would have to open the gate again was neither here nor there. My job was: clean path, rake it, close gate at 15.30 and do this promptly and punctually. So, when is 15.30? Typical of our upbringing, there was no task that did not entail the learning of another. My mother was in charge of the time. I was used to her methods of teaching and time was learned on day one of path clearing.

My work was always inspected and favourably commented on by my parents or grandparents and this was quite important to me. I was also rewarded. My work was so good that I was rewarded with lessons in knitting. My first piece of art was not a straightforward piece of flannel or scarf. Oh no, it was one pair of socks requiring the use of five needles. Well, it was just not possible to learn one job without being jollied into learning another. But it made me feel important and quite superior. It was like being given a medal. Better still, I could have some chocolate or jelly babies or pink- and white-striped peppermint. But not as many as I would have liked. Sweets came in restricted quantities.

My grandmother was ready with a toy grocery shop, with scales, weights: 1gm, 10gm, 15gm and a few more. A wooden board and a knife with my name carved on the handle by my great-grandfather. Now I could cut up chocolate. 20gm for myself, 20gm jelly babies for my sister, 20gm chocolate for my grandmother’s coffee break and other such delights. I felt like a magnanimous queen giving gifts. I could do even more than that. I could tot up all the gifts I had handed out on each occasion, 20gm + 15 + 25, and so on. For this I was given an abacus with yellow and red beads. I would push these beads about with great enthusiasm; sometimes my gifts worked out to be 80 or even 100gm in one day. I was working so hard. My mother showed me how to write these numbers down on a piece of paper, then I could take this piece of paper and read it out to my grandmother, who said I was very clever, so I could go into the garden and get her three sprigs of marjoram. ‘You know the difference between marjoram and parsley, don’t you, my dear child?’ And the ‘dear’, now very proud, little child trotted off into the garden to fetch as requested. Had I missed something? Had ulterior motives been at work? I was too innocent to recognise unobtrusive guidance. School? That was still a long way away.

One particular incident delights me still today. I was to be in charge of goslings who had been given a run in the barn annex of about 2.5m x 3.5m that I had to keep clean. Animals living in a proper stable gave me real status. We had large numbers of geese and other animals on our land. But these four goslings were set aside for me to care for. They were to be let out early for grazing and like ‘the Little Gänsehirtin’ in the fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm, I set off with them even before breakfast, having crept out of bed quietly with a little hazel switch in my hand and a book – quite big and heavy – under my arm. I walked them about in the orchard, the sun shone brightly, it was so warm so early in the day, the goslings ate their fill and nestled down to rest, so I lay down on my tummy and opened my book. It was quite an old edition of Goethe’s works and a marker had been put by my grandfather on the page with Goethe’s ‘Heideröslein’. I read it, I loved it and started learning it by heart. To my great amusement and pleasure the goslings moved closer and started to settle on the open pages and as I learnt the lines I had to keep picking up the soft little creatures, read the verses underneath and quickly memorise them before they moved back onto the pages. I did not know if they had an interest in poetry, perhaps they mistook the shimmering rays of the sun on the white paper for water. I will never forget the wonderful morning when I was in a race with little goslings to see who could get at the print first. I lived an enchanted life.

When I was four, nursery school was considered. My mother took me there in the morning and collected me again in the afternoon. But the experiment got the thumbs down on day three. My mother considered nursery school, after what she had seen of it, as inappropriate and unsuitable for me. ‘Far too childish,’ was her verdict.

So I had few playmates, but there were those cousins and I had a most beautiful silver-haired little sister with big blue-grey eyes. I also had a tiny brother. I could not see what uses he had as he could not even walk. So I largely ignored him.

My mother’s mother was a passionate cook. In her younger days she had worked in a famous Berlin Hotel near the Kaiser’s palace. Outside that palace my grandfather was serving as a guard to the Kaiser. To be chosen as a guard was an honour. You received no salary, you provided your own uniform, you came from a good Prussian landed background and your family motto was ‘Do more than your duty’. My grandfather fitted the bill. My grandmother often passed him standing outside the palace on duty. Few words could be said between them because of the circumstances. But one day as she walked by, he said: ‘Well, Fräulein, when do we get married?’ Details were arranged during the following days as they could not speak openly to each other and only a few discreet words could be said as they were in the public eye. But their plans went ahead and my grandparents, once married, moved to the family property east of the Oder.

My grandmother pursued her culinary passion. This meant an awful lot of food was cooked and it had to be eaten. This in turn meant large dinner parties all the time. For me this meant best dress was to be worn every so often. As heiress I did not have to go to bed early, instead I was standing in the line-up in the hall greeting guests and sometimes saying goodbye at ever such a late hour. I was even allowed to sit at the table, having mastered the art of how to hold a fork – quite unlike how it is held today. I was not allowed to drink wine and I considered grown-ups pretty gullible because wine was really sour, unpalatable stuff. I was given elderberry juice. It is so healthy for you but it has its own dangers: never spill it. It stains. I was a very delicate eater and drinker. Small wonder.

I liked the parties, the lampions in the garden, the cheery faces, all the talking and singing and laughing, everyone speaking kindly to me. Often I was asked to recite poems. I was vaguely aware of being some kind of showpiece and I was eager to oblige and actually loved to be praised. I was not so fond of grown-ups’ food. You ate what was put on your plate, all of it. You smiled, said thank you and that was that.

Well, the good life did not last. The parties were getting quieter, voices were kept down, sometimes the talk turned into a whisper. Something to do with a party, some undefinable unease and feeling of some kind of danger crept into life.

One day three men arrived to talk to my mother. My grandparents joined in but I was sent out of the room. I became frightened. What had happened was this: my mother had been awarded the Mother’s Cross, given in recognition to women with three or more children. My mother did not wear the Mother’s Cross; she also cancelled Mother’s Day as superfluous. If you want to be good to your mother then you can be good every day of the year, not just on one.

A large picture of a man’s head was hung on the main wall of the sitting room. It said underneath ‘Unser Führer’. And a big book was placed in a prominent space on the reception room table. The title was Mein Kampf. The picture and the book had been given to my parents on their wedding day as a gift by the registrar and my parents seemed to have forgotten to display this gift in their home. Now they had done so, oil had been poured on troubled waters; all seemed fine. But more officious-looking people arrived talking to everyone in the house about a party and saying that one should be in it, but no one in the whole house was in it. I did not understand any of it, except that it was not a good thing not to be in it. The consequences would affect us in years to come. Little did we know what wrong we had done.

One day two people with two large bags and three little girls arrived on our doorstep. There was much hugging and kissing and crying and questioning. Surprise was shown by everyone in our house. They were clearly much loved and made most welcome. The three little girls were also cousins. I had so many by now. And the grown-ups were a new uncle and auntie I had never seen before. They were going to live with us for a while. It was all so very exciting.

I was not told then what had really happened. But I found out that they had lived south of Danzig, well east of the Oder in Germany. After the Great War that part of Germany had been made over to Poland. This area, populated by Germans for hundreds of years, was now renamed ‘The Polish Corridor’. It had changed their lives drastically. They did not want to be Polish. They also believed that this turn of events would not be of long duration. But it was. Years later, when their little girls were of school age, they had to give school a miss because they were stoned on their way there. German women could only go shopping in convoy because of frequent attacks on them by some Poles. They were denied access to a doctor and in winter they were refused coal.

Winters could get very cold where I lived, the ground was frozen up to a whole metre deep, and as mercury freezes at -39°C, no one bothered to look at the thermometer on cold days, it would not tell you more than it was at most -39°C. We wore special clothing in winter, finger gloves inside mittens and then hands were put inside a muff which we children wore on a ribbon round our necks. We also wore double shoes. I really mean it. One pair was made of lined leather and a second pair, a little larger, was pulled over the top. They were called Galoschen. They had no laces, they were buttoned.

Not having access to coal and therefore no heating meant your chances of survival were slim in the long run. So my new uncle and aunt had packed two bags with treasured belongings, took their three girls and walked out on their property, their house, their fields, their lives’ work and had run for it. Better empty handed but alive.

My uncle was very knowledgeable in the production of certain foods and was soon made manager of a local factory and they all moved into a very, very large house. I loved my new family members, they were all so cheerful and musical. They had such beautiful voices, like almost everyone in my family. Did I mention that all of my family loved opera? There was hardly an aria or duet or a chorus from any opera that I had not heard. My new auntie could go one better: she knew all my little poems and if they had been set to music she would sing them for me. She knew not only the folksong version but also the versions created by famous composers.

How little joy was left for all of us and how short a life for most. Thinking back to that time now, I feel ice-cold terror creeping up on me. What a mercy that we could not look into the future.

School

Then in 1939 came the day in early September when I was allowed to go to school. What a highlight of my life. I wore the biggest bow ever in my hair. I had a creaking, squeaking new leather satchel, a gigantic cone-shaped stiffened paper bag in my arms, almost as big as me, the top held together with crêpe paper and a huge bow. It was filled with chocolates and sweets of all kinds and all the family and uncles and aunts accompanied me to school. There we met other children also accompanied by their families and, like me, carrying big, big sweetie bags. We were introduced to our teacher, quite an elderly gentleman who had taught my father when he was a little boy. What an incredible day.

The school building had large rooms with big windows and a huge school yard with very high iron spiked railings all round it. I was used to climbing quite tall trees and saw at a glance that these railings would be hard to climb. I naturally thought that the school yard was for playing in. I could not have been more wrong.

On that first day speeches were made to which I paid no attention. There was too much to see and I was thinking about the contents of my Schultüte, which could be opened when I got home as a reward for going to school. Some older children sang for us, which ended my first day of school. I skipped home triumphantly and there I could empty my enormous sweetie bag and distribute all the sweets. It was like dipping into Aladdin’s cave. And all because I was so fantastic and clever and had gone to school.

I loved school and all my new friends. I knew the way well and was allowed to go by myself. I did not walk, I ran all the way, even waving my books to show everyone I met that I was a big girl and on my way to school. One day, it was the same September, I was running home; I could not wait to get back to tell everyone what I had learned that day. Halfway home I met my father coming towards me carrying a suitcase. He put it down and laughed and picked me up and swung me round and said, ‘Run, little princess, run; run up to the field with the railway line. I am going on a journey. I will be on the train and will wave to you. Everyone is already there waiting for you.’

Now, that was something really exciting. I laughed and waved as he hurried away from me and he waved back until he was round a bend in the road. I arrived breathlessly at the top of our field which was crossed by a railway line. Apart from my immediate family a lot of other people had already gathered there. But they were so quiet. I felt uneasy, something was wrong, why shouldn’t you cheer when someone came by on a train and wave? But not so, some older women even cried.

My mother held my sister’s hand and had my little brother on her arm. ‘Come here, my child and wave when Daddy comes by.’ The train arrived. I could not believe so many heads looking out of the windows, so many arms waving. The air was full of voices. I recognised Daddy, laughing and waving. ‘Bye bye, keep your beak up, good luck.’ And the train disappeared in the distance. Then all was silent, except some women were crying helplessly. I was puzzled. People looked devastated. What was all that about? My mother ushered us home.

Home was strange, also silent, empty. Where was everyone? My uncles all gone. Only my great-grandfather and my grandfather were left. My grandfather was not allowed to go on the train. He had a crippled left arm. He had suffered his injury to his arm in the Great War before I was born. He was in a Prussian regiment with that motto, ‘Do more than your duty’. I was always awed by this as it summed my grandfather up so perfectly. All the people who had helped to work the fields had also disappeared, as had all the horses. ‘Just like the Great War,’ my grandmother said. ‘The men and horses go first.’

I did not understand. What was to become of us? I knew enough about farming to grasp immediately the enormity of it. Who would sow the rye and plough the fields and in spring plant the potatoes? How would we get food for ourselves and the remaining animals? My grandfather had about 200 special rabbits. They were chinchillas and needed lots of hay in winter. Who would bring it in from the meadows? Max Schmeling was a friend of my grandfather. He also bred chinchillas and often called at our place. I did not know that he was a famous boxer. He was just uncle Max – and a very jolly uncle he was, who didn’t find it beneath him to ‘talk rabbit’ with a little girl. Anyway, between the two of them they knew someone who knew someone and one day in autumn a large wagon, loaded high with hay, arrived in our yard drawn by two huge Belgian horses. They were ‘exempted’ horses, whatever that was. And in times to come I became well acquainted with them.

The house became quieter still. All the women went to factories, except my mother. She had more children than the other women in the house and was expecting another. So she was put in charge of all the other children so that their mothers could also go to work. Now all my cousins were her children as well. This meant she had no time to work in the garden or in the fields. This was a disaster. I was very young, but this situation filled me with panic. It meant no food, not for us, not for the animals, for no one.

Then my grandmother was ‘enlisted’. She was actually very ill with a heart problem. But the person who had come from the Party said she should work for her Fatherland and also asked whether she expected any pay or whether she would volunteer. I remember her saying to my mother that evening, ‘What could I possibly say but just ask for the minimum to pay for essential services?’ My grandfather with his crippled arm was also ‘volunteered’. That left my mother with nine children in our big house, with me being the eldest, and my great-grandfather. The outlook was more than bleak, like staring into an abyss.

The sting in the tail was this. We were not in the Party. That meant all men not in the Party were called up first to fight for their Fatherland, whether they had one or a dozen children. There was no promotion, so they remained on a private’s pay leaving their families in financial distress. Family men were denied leave for Christmas. The disadvantages were accumulative, particularly as Party members were allocated extra food ration cards as a reward for loyalty to the Führer. In later years my mother said, ‘We had been downright stupid. Forget principles and high ideals. Of prime importance is to stay alive and bend with the wind and adapt and survive whatever is thrown at you.’

There had been many people who had been cleverer than us, but later it turned out that my mother was a highly intelligent and quick-witted learner and she became a survivor extraordinaire; in a class of her own.