Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

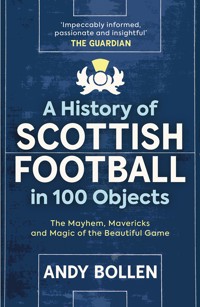

- Herausgeber: Arena Sport

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

From Socrates to Arthur Montford, via Bovril, Buckfast and, of course, pies, this is a unique journey through the extraordinary world of Scottish football. Packed with anecdotes and observations, Andy Bollen wallows in a nostalgic haze, a time of hatchet-men with moustaches, a magic sponge that should have been granted miracle status and big-money strikers who couldn't hit a cow's posterior with a banjo. Opinionated, forthright and funny, Bollen reluctantly concedes that tattoos, hair weaves and VAR are now part of the game. This idiosyncratic ride through the wonderful absurdity of Scottish football will chime with every fan.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 385

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This edition first published in Great Britain in 2019 by

ARENA SPORT

An imprint of Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.arenasportbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Andy Bollen, 2019

ISBN: 9781909715738

eBook ISBN: 9781788851688

The right of Andy Bollen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Polaris Publishing, Edinburghwww.polarispublishing.com

Printed in Great Britain by CPI Books Ltd

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

MAIN HALL: Mavericks & Characters

1. Chic Charnley & the Flashing Blade

2. Cult Heroes

3. Flawed Genius

4. Moffat v Souness

5. Gazza’s Magic Flute

6. The Hatchet Man and the Art of Tackling

7. Jinky’s Rowing Voyage

8. James McFadden’s Missed Flight

9. Willie Johnston’s prescription

10. Frank McAvennie

11. Jim McLean v John Barnes

12. Puskás in Drumchapel

13. Mo Johnston

14. Rab C Sócrates

15. Battle of Bothwell Bridge (2000)

GALLERY ONE: Tactics, the game & the duffers

16. The Coaching Badge

17. Duffer Signings

18. Goalkeepers

19. Giant Killer & Shockers

20. The High Press

21. The Ten Men Myth

22. Sand Dunes

23. Sitters (The Iwelumo Wing)

24. Strachan’s Stretching Machine

25. Think Tanks

26. Parking the Bus

GALLERY TWO: Media, Communication & Technology

27. Scotsport Arthur’s Jacket & Stramash

28. Bob Crampsey

29. Cliché

30. Fanzines

31. Football on TV

32. David Francey

33. Losing the Dressing Room

34. iPhone

35. Outside Broadcasts

36. Public Address Systems

37. Twitter

38. Adjutant v Alex Cameron

39. Wi-Fi

40. Scotsport Jumps the Shark

41. The Phone-in

WING: Culture

42. Agents

43. Aluminium Studs

44. Car Watchers

45. ‘Dirge of Scotland’

46. The Existential Side-Aff

47. Golf

48. The Lift-over

49. The Magic Sponge

50. The Mining Holy Trilogy Cliché

51. The Quagmire

52. The Smell of a Saturday Morning

53. Rod Stewart Cup Draws

54. Trialists

55. Urinals

56. The Vinyl Frontier

57. Bad Taste in Boots

HALLWAY: Hair, Tats and Tash

58. Comb-Over

59. Hairdos & Hair Don’ts

60. Mowsers

61. Tattoos

62. Weaves

COURTYARD: Food and Drink

63. Argentina 1978

64. Bovril

65. Buckfast

66. The Postmodern Fish Supper

67. A Pie

68. The Wagon Wheel (Macaroon Bar, Chewing Gum)

WING: Vice

69. FIFA

70. Barry’s Bar Bill

71. Betting & Gambling

72. Bung

73. The Copenhagen Five

74. UEFA

WING: Modern Life is Rubbish

75. Aberdeen’s Gallus Seagulls

76. After Dinner Speakers

77. Virtual Football

78. Crying Fan

79. European Coefficient

80. Gardening Leave

81. Officious Stewards

82. Snoods (and Gloves)

83. Hand over Mouth

84. Headphones

85. The Academy Player

86. Smoke Bombs & Flares

87. International Breaks/Winter Breaks

88. Mascots

89. Synthetic Surfaces

90. The Play-Offs

91. The Season Book

92. Time Added On

93. Vanishing Spray & Shocking Referees

94. VAR Goal Line Technology

95. War Chest

GIFT SHOP: Merchandise

96. Football Cards

97. Football Programme

98. The Overwrought Memoir

99. The Panini Sticker Book

100. The Replica Kit

EXIT

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To Sharron

INTRODUCTION

Welcome to the Alternative Scottish Football Museum. We hope you enjoy your visit. Please take your time to look around the exhibits on display in each of our great halls, wings, nooks and quiet, more reflective rooms.

I’m Andy Bollen, the museum curator, and I’ll be taking you on a guided tour through the eclectic history of Scottish football in 100 carefully selected objects that typify the game north of the border. Our exhibits range from Jimmy Johnstone’s oar to Aggie the tea lady’s trolley, Panini sticker albums and the unique taste of Bovril. Learn why Puskás and Socrates should have been Scottish, just how versatile a dubious meat pie can be, and explore a range of wonders old and new – from Arthur Montford’s jacket to the phone-in, Buckfast, vanishing spray, Twitter, VAR technology and flares (pyrotechnics, not 1970s attire). These exhibits distil the beauty of the Scottish game, standing as testament to the collective hypocrisy and foolishness which links these people, places and items to the nation’s favourite drug: football.

Any questions?

Wonderful. Let’s begin. Please follow me this way . . .

MAIN HALL

MAVERICKS&CHARACTERS

Exhibit 1

Chic Charnley & the Flashing Blade

Welcome to the main hall of the museum and to our first exhibit.

Traffic cones have become a familiar motif in the cultural fabric of Scotland’s biggest city, Glasgow.

There’s the famous one, set at a jaunty angle, on top of the Duke of Wellington statue. City chiefs regard it as vandalism and high treason, but it is loved by the people and stands as part artistic statement, part humour, part healthy disregard for authority. The coned statue, which stands outside Glasgow’s Museum of Modern Art, is now a city landmark in its own right.

Then there’s the other traffic cone, involving the footballer, Chic Charnley. It, too, has its own place in Glasgow and, by extension, Scottish football folklore.

Charnley is among the last of a generation of cult heroes to ply his trade in the Scottish game. His career spanned more than twenty years, starting at St Mirren in 1982, and taking in spells at clubs such as Hamilton, Hibernian and Dundee, yet he is probably best remembered for his four spells with Partick Thistle . . . and the seventeen red cards he amassed over his career.

Charnley was the classic football contradiction: the hot-headed rogue with a heart of gold; the bampot who could play; the prodigious, left-sided maverick who, when he stayed on the park, was (in Scotland at least) one of the modern greats.

It’s fair to assume that Charnley will be glad he’s out of a game that would be unrecognisable to him now. One full of academy players, strict diets, feeble tackling and softened by too much money, too soon. He came from the mean streets and played football for the love of the game, not money.

However, Charnley gains entry into the Alternative Scottish Football Museum not for this but, instead, for a clash he had with two locals who dared question his footballing ability.

In the 1990s, Scottish football was broke. Many clubs operated without training facilities or academies and would often train on any available public park they could find, placing their players at the mercy of local kids with seemingly nothing better to do than hit golf balls at them.

On one fateful occasion, after receiving abuse from a couple of locals while training in Ruchill Park with Partick Thistle, Charnley challenged his abusers to ‘take it outside’. Since they were already outside, he rescheduled, inviting them to return after training for a square-go. As a dedicated, professional athlete, he would let nothing get in the way of his day job.

The challenged pair returned later, wielding a samurai sword and a dagger and accompanied by a dog that appeared to have been spawned by Satan himself. Charnley, unfazed, attacked them with the only weapon he had at his disposal – a traffic cone left behind after training. Like Jackie Chan taking down a room full of assassins with whatever props were available to him, Charnley went to work. The devil dog soon realised that it was up against a wilder creature than itself and quickly scarpered. Seeing the dog head for freedom affected the focus of its owners and they, too, made a break for it, though not before one left Chic with a scar on his hand from the attack. As the erudite Observer journalist, Kevin McKenna, would explain in his column in April 2010, ‘Charnley had been raised in the neighbouring arrondissement of Possil where to survive the week was to have endured your own personal Passchendale.’

Of course, let’s not forget, this was Charnley’s workplace. How many people have staged a re-enactment of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai in their office? The incident, as bizarre and ludicrously lampoonish as it sounds, established a place for Charnley forever in Scottish football lore – and thus his place as the first exhibit in this museum.

Charnley’s default position was always to hit back and it was a trait that followed him throughout his tempestuous career. His trouble, though, wasn’t only fighting numpties in Ruchill Park, or flare-ups with opposition players. His charge sheet includes the time he smacked his St Mirren manager, Alex Miller, with football boots, not forgetting his ignominious exit from Clydebank for punching his coach, Tony Gervaise. There was also a fracas in Love Street when he played for St Mirren against Dundee United and cracked Darren Jackson’s jaw, which started an almighty riot in the tunnel and saw the opposing managers, Davie Hay and Jim McLean, come to blows.

Charnley’s career took him to seventeen clubs (he’s credited as playing for Cork City but didn’t), which included four stints at Partick Thistle, two at St Mirren and what many consider his most successful two seasons: at Dundee in 1996/97, and then at Hibernian the following season.

The transfers point to an impatient personality, someone who needed to be handled in a certain way. He was a lightning rod for chaos and havoc and it’s a wonder he managed stay in the game for as long as he did, drowning in systems and tactical strategies and strangled with over-coaching. He would thrive under managers who knew how to get the best out of him, managers like the inimitable John Lambie, who encouraged his direct style of play and allowed him the freedom to express himself.

Unlike most of today’s young stars, Charnley only played a few times for his secondary school team and some Boys Guild football. He was too busy watching his childhood team, Celtic, both home and away, when he should have been playing. It wasn’t until an uncle noticed his talent and pushed him to train that he narrowed his focus and joined Possil Villa and, later, the junior side, Rutherglen Glencairn.

James Callaghan Charnley was a delightful player but his unstable behaviour often overshadowed his will to entertain. To the purist, he was a walking liability; to the fans, he was a wizard who clearly understood he wasn’t too far-removed from the punter paying at the gate. Perhaps his desire to entertain stemmed from an understanding that he’d not long left the terraces himself.

His greatest personal achievement occurred when he turned out for Celtic after then manager Lou Macari invited him to play in a testimonial match for Manchester United forward Mark Hughes. The call came while he was in the pub, midway through a mammoth session. He hung up the phone and decided to travel down to Manchester with pals, change into his suit and get dropped off at the team hotel with his boots in a plastic bag.

Charnley later claimed it was too much for him when, throughout the warm-up at Old Trafford, the Celtic fans sung his name. He was so moved by finally achieving a lifelong dream of pulling on the famous ‘hoops’ that all he did was cry. In one photograph from the match, Charnley is caught smiling as he skips away from United legend Eric Cantona, no shrinking violet himself. Charnley had deliberately kept his legs open to invite Cantona to nutmeg him, then quickly closed them and run off with the ball.

Charnley was one of the best players on the park that day. He set up two goals and did enough to earn a contract but Lou Macari, who would soon be sacked by the Parkhead hierarchy, took the fact Charnley holidayed with his Thistle teammates instead of accepting a three-week tour with Celtic in Canada as a snub and blocked a permanent move.

In April 2018, discussing the death of his mentor and friend, John Lambie, on Radio Scotland’s Sportsound show, Charnley gave his version of events. He stated Macari had spoken to an unnamed former legend at the club who advised against his signing. Like football tends to do, time moved on quickly and the moment passed. However, it’s a scenario many neutrals would’ve enjoyed.

Now working as a taxi driver, Chic Charnley is still seldom out of the news. He recently ferried a group of Rangers supporters whose bus had broken down to their game for free. They might be rival supporters but they were genuine football people needing to get to see their team. News also emerged of a woman who Charnley talked out of taking her life.

A maverick, a one-off and a true football man, Chic Charnley was, and remains, one of Scottish sport’s most fascinating enigmas.

Exhibit 2

Cult Heroes

Elevation to ‘cult status’ varies from team to team.

In a traditional footballing sense, the hero is usually regarded as ‘an honest big player’, with ‘loads of heart’, who is ‘solid in the tackle’, ‘gives his all’ and, preferably, is ‘one of our own’, having actually supported the club as a boy.

Such players are usually loved because they display regular elements of psychosis and brutal levels of dedication, which endear them to the support. They play with a ‘no nonsense’ approach, are commanding in the air and are physically dominant. It’s not a requirement but they usually have a broken nose and have lost their front teeth in battle. They’re often unfashionable and, no matter the opposition, always throw themselves in the line of fire.

They’re that guy.

In the 1970s, the legendary Manchester United player and Scotland internationalist, Jim Holton, married my mother’s cousin, Nessie McLaughlin. This promoted him instantly, as befits the warped outlook of a football-mad kid, to my uncle. Holton was the performance of the cult hero at international level. Powerful, unrelenting and committed. He even had his own terrace song, a reworking of the eponymous number from Jesus Christ Superstar: ‘Six foot two / Eyes of blue / Big Jim Holton’s after you.’ Incidentally, ‘Uncle Jim’ was six foot one and had brown eyes.

As for other club cult heroes, sometimes players who are otherwise awful become weirdly iconic in return for something as simple as scoring a single sublime goal. In 2002, the much-maligned Dutch centre-half Bert Konterman scored a 30-yard thunderbolt for Rangers against Celtic at Hampden in the CIS League Cup semi-final, laying waste to Celtic’s treble hopes in the process. Rangers also had ‘Big’ Tam Forsyth, or ‘Jaws’ as he was known. They also had the ‘Tin Man’, Ted McMinn.

At Celtic you’d think Bobo Balde would be a perfect candidate for cult hero status, but he blotted his copybook towards the end of his eight-year spell at Parkhead by choosing to run down his lucrative, £28,000-a-week contract from the fringes of the first team. Jóhannes Eðvaldsson and, in his two seasons he spent at the club, Thomas Gravesen would fit Celtic cult status. Then there’s ‘Mad’ Martin Hardie, a bona fide Partick Thistle icon. And, of course, it would be remiss to overlook the aforementioned Chic Charnley.

Airdrieonians goalkeeper John Martin was always good for a ‘red top’ photo op. So too Stevie Gray and Justin Fashanu, who, despite only making a handful of appearances for ‘The Diamonds’, nevertheless became a cult hero. Albion Rovers had Vic Kasule and Ray Franchetti. Motherwell had Brian Martin. St Johnstone had Roddy Grant. Hibs had George Best. Aberdeen had Doug Rougvie. Dundee United had Hamish McAlpine.

Scottish football has had many cult heroes, but they shouldn’t be confused with ‘fans’ favourites’. Paul Sturrock’s fifteen-year love affair with Dundee United is a good example of where the distinction must be made. A loyal servant? Yes. A prolific goalscorer? Absolutely. A hero amongst the terraces? Unquestionably. But categorically not a cult hero in my mind, despite many polls saying otherwise. Claudio Caniggia was a fans’ favourite during his short spell at Dundee, as were Franck Sauzee at Hibs and Jose Quitongo at Hearts – but none are cult heroes, in my opinion.

Players rarely stay at the same club long enough to establish their cult status. The cult hero would deck an opponent with a left hook, or go in goal if all the subs had been used up and the team needed a ’keeper. The cult hero would breach the club’s code of conduct by ignoring a drinking curfew forty-eight hours before a game. He’d get pulled over zooming around Edinburgh’s Old Town, going the wrong way down a one-way-street with Dwight Yorke and loads of lassies in the back . . . a typical night out for Russell Latapy during his time at Hibs!

Exhibit 3

Flawed Genius

‘Flawed genius’. A hideously overused expression yet, like most clichés, it endures as there is, generally, a huge dollop of truth contained within it.

I’m sure every country has its fair share of flawed geniuses but, in Scotland, there seems to be something in our DNA which produces more than the global average. We love the flawed genius so much, we even imported some to our game. George Best and Paul Gascoigne immediately come to mind.

More recently, Hibernian may have had Garry O’Connor, Derek Riordan and Anthony Stokes but they were wee laddies compared to George Best and his 1979/80 season at Hibs. At first, the public was dismissive of the mercurial Northern Irishman’s move to Edinburgh. This was Best in his ‘Fat Elvis’ period, a jaded star on both the wane and the wine. And yet he was handsomely rewarded for his trouble. Best reportedly received £2,000 a week from Hibs at a time when some of his teammates were on £120. Still, the investment paid off immediately, with 20,000 fans cramming into Easter Road to witness his home debut against Partick Thistle. At this juncture, it might be helpful to imagine the classic Irving Berlin number ‘Let’s Face the Music and Dance’. At the start, the song advises ‘There may be trouble ahead’. So it came to pass with Best and Hibs. On the eve of a cup tie against Ayr United, rescheduled for a Sunday because it clashed with a Scotland-France rugby international, the Hibs team decamped to the North British Hotel in Edinburgh. After the rugby, Best met up with French captain Jean-Pierre Rives and Debbie Harry of Blondie. At eleven o’clock the following morning, the party was just starting to wind down. Hibs won 2-0, no thanks to Best, who missed the game. It was an incident typical of his time in Scotland, which lasted just 325 days, during which he played twenty-two times for the Hibees and scored three goals.

Gascoigne lasted longer at Rangers – a whole four seasons, in fact – but his life off the field (and sometimes on it) was every bit as eventful. He scored thirty-nine goals in 103 games for Rangers but made as many appearances on the front pages of newspapers as their back.

Neither Best nor Gazza was Scottish but they clearly enjoyed the hospitality and genuine warmth shown towards them when they played here.

Jim Baxter is probably our homegrown version of George Best. Lavishly talented, regularly controversial and perhaps a little too well acquainted with the bevvy. Jimmy Johnstone’s career may have stalled if it hadn’t been for Jock Stein’s relentless attempts to keep him out of the pub. Then there were those like George Connelly of Celtic, an enormous talent but fragile and fraught with it. These were players who weren’t cut out for the job they appeared to excel in.

But none comes close to the flawed genius of Hughie Gallacher.

Born in Bellshill in 1903, Gallacher played 129 times for Airdrie, scoring 100 goals. As one of the cornerstones of the team’s Scottish Cup win in 1924, he caught the eye of Newcastle. After making the move to Tyneside, he soon became a firm favourite in the north-east of England, scoring 143 times in 174 appearances and captaining the club to its most recent league title in 1927. His drinking, though. It was the stuff of legend. Reportedly fond of a drink before a game, never mind after, Gallacher was eventually offloaded by Newcastle to Chelsea. During his four seasons with the ‘Blues’, he was arrested for fighting Fulham fans and fell out with the board over wages. The fact he managed to bang in eighty-one goals in 144 appearances was almost a footnote to his time there.

Gallacher was said to be the same man off the park as he was on it: fearless, ferocious and quick to anger. Imagine a composite of Diego Maradona, Liam Gallagher and Garrincha – a World Cup winner with Brazil and serial womaniser who succumbed to liver disease while in an alcoholic coma, leaving fourteen children behind – and you’re halfway to Hughie Gallacher.

Gallacher left Chelsea for Derby but spiralling debts and a costly divorce left him bankrupt. His transfer fee was given directly to the courts.

He represented Scotland twenty times scoring twenty-four goals and was one of the acclaimed ‘Wembley Wizards’, playing in the side that beat England 5–1 in 1928.

After bouncing around the lower leagues, he retired from football in the late 1930s and settled back in the north-east. At one point, he tried his hand as a sports journalist before settling on a new life as a labourer. When his second wife died, he started drinking heavily again and was involved in a domestic incident, an argument with one of his children. Gallacher overreacted, throwing an ashtray at his son, Mattie. The boy ran out of the house to look for his older brother, Hughie Jnr, and a neighbour called the police. Gallacher was arrested for assault and ordered to appear in court.

Gallacher continued to drink heavily and, suffering from what would today undoubtedly be diagnosed as depression, he struggled to forgive himself for hurting his own son. At the age of fifty-four, he went to Low Fell in Gateshead, to a spot known locally as ‘Dead Man’s Crossing’, where he threw himself in front of an oncoming train.

Mercifully, society’s attitudes towards mental health, alcoholism, gambling and other addictions have since changed dramatically and for the better. Today, there are better structures and systems in place to provide treatment and support.

Being a ‘flawed genius’ is a heavy burden to bear – but in an ever-awakening society, it thankfully no longer needs to be carried alone.

Exhibit 4

Moffat v Souness

For twenty-seven years, Aggie Moffat was St Johnstone’s tea lady before, at the age of sixty-two, she hung up her apron in 2007.

The way many people show unstinting loyalty and unbridled devotion to a club is one of the peculiarly charming aspects of football. Unlike Aggie, however, most manage to stay out of the spotlight.

Aggie started out by washing the strips at the Perth club’s old Muirton Park home in 1980, while her late husband, Bob, made sandwiches. Such invaluable members of staff aren’t there for the money or the glory, yet they give more – considerably more – than many of the handsomely rewarded staff.

Aggie soon took on catering duties and, over the course of her career, looked after a string of managers and hundreds of players. She seemed to do everything: the laundry, the tea, the cleaning, you name it. According to local legend, she also made a mean pot of soup.

In the outlandish and often infantile arena of professional football, Aggie staunchly insisted on politeness and old-fashioned manners. She didn’t like players getting above themselves and kept the big heads in place while, at the same time, keeping a maternal eye on many of the younger players, often taking them under her wing.

Most football clubs have many similarly invaluable staff behind the scenes who don’t take any nonsense. Managers, coaches and directors love them. They possess hearts of gold, are loyal and are cheap to employ. They are the pillars behind the scenes and everyone knows it’s important to look after them and treat them with respect.

So it was that Aggie rose to national prominence in 1991 when she had a spat with the then Rangers manager, Graeme Souness.

Many of the players Souness came up against in his twenty-one-year career, lived in fear of his ferocious reputation – but Aggie Moffat proved a formidable adversary.

It was 26 February 1991 and Rangers were heading toward a third Scottish League title when Souness’ men dropped points to the mid-table ‘Saints’. Souness was livid with his side’s performance and, in his post-match outburst, let rip, smashing a pot of tea against the dressing room wall. When Aggie learned of this, she confronted Souness in the corridor, facing up to one of the most uncompromising players the country has ever produced. She hailed from a time when you took pride in your belongings, your own space, and it didn’t matter how big you thought you were; you behaved appropriately or suffered the consequences.

Naturally, the tabloids lapped it up when they learned that Souness had been brought to task by a tea lady. The story became one of class warfare and, just for good measure, it unfolded right in front of St Johnstone’s owner, Geoff Brown, who found himself in the role of peacemaker. ‘Leave it, Graeme,’ he could be heard to implore. ‘It’s not worth it!’

Like most major heavyweight clashes, the two would have a rematch. The second contretemps was caused by dirty boots in the dressing room. Souness would later claim the petty arguments with a tea lady were the tipping point, the straw which broke the camel’s back and convinced him to leave Rangers and take up the offer of the manager’s job at Liverpool.

On the one hand, you had Souness claiming he had grown sick of the parochial ways of Scottish football. On the other, you had certain elements of the press pointing the finger at Aggie Moffat for driving Souness from his high-profile job at Rangers. In reality, the architect of the move was Souness’s agent, who couldn’t drive his client to Anfield quickly enough.

Aggie quickly learned how the media worked and, as if imbued by the spirit of Muhammad Ali, she began to shoot from the hip. ‘He’s just a plonker,’ she opined. ‘He always will be. I never liked the man and I never will. If he had come back next season I would have finished it. His nose would have been splattered all over his face. That’s the only thing I regret not happening. That I didnae finish it. I should have broken his big nose.’

Aggie Moffat will always be remembered for her run-ins with Souness, yet that doesn’t tell anything like the full story of a devoted football club employee who didn’t seek the limelight, worked hard, and whose husband and family were everything to her.

Muirton Park and, later, McDiarmid Park were her workplaces and she was immensely proud and protective of them. Everybody who crossed their doors was expected to behave. It was that simple.

News of her death broke during the writing of this book. The outpouring of tributes, especially from those she looked after, were overwhelming and emotional. I considered removing this exhibit, before deciding that it perfectly summed up what makes Scottish football so special – how something as trivial as a fall-out can be elevated so quickly into a dramatic national story.

Aggie died on 14 April 2017 at the age of seventy-two. She is, and long will be, both dearly missed and fondly remembered.

Exhibit 5

Gazza’s Magic Flute

In truth, any football museum wishing to cover sectarianism deserves to be met with incredulity. It’s not an easy topic to deal with but it would be remiss to ignore it. And so this alternative museum includes a flute to remember the time that Paul Gascoigne mimicked playing ‘The Sash’ – a famous Northern Irish loyalist song, forever intertwined, in Scotland at least, with sectarianism – during an Old Firm clash in 1998.

The moment is forever remembered both for its idiocy and the scandal it prompted.

This being Scotland, the media stoked the fires, bringing the story into the mainstream and catching the interest of folk not normally interested in football. Folk like politicians, who quickly jumped on board, turning the story into a wider societal issue. Before we knew it, Gazza stood accused in the court of public opinion of being the lightning rod of everything Orange.

The mercurial Englishman, it was widely agreed, was guilty of little more than bad judgement and being what your nan might have called ‘a bit of a stirrer’. The more serious questions should have been asked of those around him who knew better than to goad him into it. In truth, you also have to question the mentality and motivations of those who get upset by a man pretending to play an invisible flute. I may be wide of the mark here but I truly think most football fans, with any degree of common sense, thought Gazza was an idiot, not a raging bigot.

The SFA’s Jim Farry described it as ‘unprofessional and inflammatory’. He made it sound like Gazza should have practiced his scales and his imaginary flute-fingering before bringing his party piece to the pitch.

I wasn’t upset by Gazza’s invisible flute playing but, as soon as I saw it, I knew he’d get slaughtered. There’s a blatant double-standard there, of course. It’s not uncommon for a player to be subjected to vile abuse from the stands for ninety minutes yet, when they retaliate with ‘something inflammatory’, they’re accused of starting a riot. For the record, no riots followed Gazza’s moment of madness

To me, the whole episode was more ‘Monty Python’ than anything more sinister. He was being daft and trying to provoke a reaction from fans on both sides. Gazza was the type of player who would have jumped into the Clyde if it got him a laugh.

I’m perfectly willing to go out on a limb and say Gazza didn’t know about the Battle of the Boyne and 1690 when he did this. Of course, when he did it again later in his Rangers career, playing an invisible flute whilst warming up in front of Celtic fans, it proved what many had long assumed: that his brains were solely confined to his feet.

The incident cost Gazza £40,000 – two weeks’ wages. An expensive lesson.

Exhibit 6

The hatchet man & the art of tackling

The ‘hatchet man’ has become something of a lost figure in Scottish football. A man forgotten in the mists of time. He was a different breed of player and should not, under any circumstances, be confused with a team’s ‘hard man’. The hard man can be five foot nothing and more like a wee, narky, Al Capone; the mental guy who loves a fight and often deliberately goes looking for one as soon as the ref blows his whistle. The hatchet man, on the other hand, was (past tense here) usually a cult hero centre-half or holding midfielder: ferocious, hard as nails and the type of guy who, after hanging up his boots, would become a God-fearing prison officer. The hatchet man was always acutely aware of his job. He revelled in knowing exactly how to intimidate his opponent. He was focussed, singular, calculated. He knew how to ruthlessly win the ball and then, if the ref allowed play to continue while his opponent floundered on the turf in agony, find the silky creative midfield playmaker.

His weapon of choice – the imperfectly timed and viciously executed tackle – is a dying art and widely frowned upon these days, yet in the era of Ralgex, the magic sponge (with more bacteria than a decaying fox) and a halftime ciggie, it was an intrinsic part of the game. In the glory, gory days of blood and snotters, the two-footed lunge was the norm; the crunching, late, over-the-top tackle, a rite of passage. Three factors have combined to bring the art of tackling to the edge of extinction: foreign managers, referees, and literally hundreds of television cameras capturing every moment of brutal savagery.

Awarding the dubious honour of ‘football’s most notorious hatchet man’ is surely dependent on your age. For my generation in Scotland, it would have to be Gregor Stevens. He played for many clubs in the 1970s and 1980s, including Motherwell, Leicester City and Rangers. He brought a mix of scything brute force and psychotic pragmatism to his game. Stevens will always be tarred with what some people might consider a distinct lack of natural talent and it was probably frustration at this that made him dirty as a player – yet he was able to carve out a long football career in between red cards, suspensions and fines because managers such as Jock Wallace saw the value of having an ‘enforcer’ on the field. They understood they couldn’t have silk without steel.

Graeme Souness could be brutal and, as he approached the end of his career, he had earned the right to play on the edge at times.

Older fans will fondly remember John Blackley at Hibs and Dave Mackay at Hearts. Celtic’s Roy Aitken never took any prisoners, was 100% committed, hard, but also fair. Cammy Fraser played in a struggling Rangers side before the Souness revolution. Terry Hurlock briefly joined Souness from Millwall for £375,000, played thirty-five games, was booked twelve times and sent off once, but his robust contributions are still fondly remembered by the Ibrox faithful. Dundee United had Davie Bowman and Aberdeen had Doug Rougvie.

Scotland can occasionally have its moments of violence but the scarcity makes it more enjoyable when the odd brawl flares up. For some strange reason, even during the darkest days, players would knock the living daylights out of each other on the park yet be best mates off it. Players like Bertie Auld and John Greig were hard because it was the only way they could survive. So, as we look back to the era of the hatchet man, maybe we should celebrate the fact that the players from both sides were able to share a drink together afterwards, leaving their competitive thuggery out on the field – just as we now leave them in the past.

Exhibit 7

Jinky’s Rowing Voyage

It barely seems plausible that somebody with such wonderful balance, skill, low centre of gravity and a mind capable of intricate movement and trickery could be so hopeless on a boat. And yet when Celtic’s Jimmy Johnstone was cast adrift in a rowing boat, his seamanship wasn’t helped by the fact that he was without any oars – and was completely plastered!

Can you imagine such capers today? Messi, Neymar or Ronaldo, adrift off the coast of Largs on a boat? This, though, was a different time, a time when footballers lived in, and remained part of, the community. Even those who moved to leafier parts of town stayed in touch with school friends, remained connected to the community and kept their feet on the ground. These were the halcyon days of Scottish football, when coaching manuals and badges were set aside and managers considered players getting pissed together as ‘team building’.

Arguably one of the best footballers this country has ever produced, ‘Jinky’ Johnstone is fondly remembered for this comical incident which happened while staying at Largs with the international team. It almost came with the territory that the impish maestro, an exuberant whirling dervish on the pitch, full of trickery and mischief, was also the clown prince off it.

It was late on a Tuesday evening in 1974. Scotland had just beaten Wales, and were weeks away from heading to West Germany for the World Cup. The manager, Willie Ormond, allowed his players to partake in a few drinks, knowing they would sweat it out in training before the final Home Internationals match against England that Saturday. It was around five in the morning when the players were thrown out of the pub and were walking along the seafront back to their hotel. As many a poet, writer and playwright will attest, the sea wields an intoxicating strength, reminding us of our insignificance before its vast power. It lures us with a magnetic pull and being on the lash until the early hours of the morning helped entice the players toward the water . . .

When inebriated, an anomalous logic takes hold. One which makes the idea of rowing out to sea seem like a perfect way to clear the head. Easily cajoled, Jinky jumped aboard a small rowing boat and was shoved off by his pals. He stood up and started singing, unaware that the boat was caught in the tide and was now setting sail for the horizon. Davie Hay and Erich Schaedler were the first to notice things were going awry. They manfully decided to go out and save the day. However, both of the boats they chose started leaking. Denis Law recalls seeing Jimmy’s boat getting smaller and smaller as it faded into the distance. In the end, the coastguard was called and the stricken winger’s rescue made headlines as the national team built up to the traditional end of season match against England.

Johnstone woke up in the hotel the next morning and started piecing together events of the previous evening. When he managed to make it down for a late, late breakfast, around midday, Law started singing, ‘What shall we do with a drunken sailor’. The manager wasn’t happy and Jinky was cast adrift yet again – this time to face the baying press pack, who wouldn’t buy the excuse that he’d decided to go fishing. The way the press painted the picture, it was almost as if he had been heading for the Atlantic bound for Nova Scotia. The reality was that he was on the Firth of Clyde. It would have taken the skill of Columbus and Magellan to navigate by Millport and down around Arran, by Campbeltown and then Islay, before setting sale across the Atlantic. They made a pariah of him.

It would be inaccurate to assume that generation was forever drinking. In Johnstone’s case, especially under Jock Stein at Celtic, he was expected to be supremely fit. Remember, Stein had moulded and trained a team fit enough to out-run, out-pass, out-jump and out-fight a much-fancied Inter Milan in the searing heat of Lisbon in the 1967 European Cup final. Rangers’ players also won the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1972 in the baking heat of Barcelona. Not to glorify the archaic notion of ‘running it off’, these players could get hammered and still perform for club and country at an elite level. Modern medical teams and fitness coaches understand that alcohol is bad for you but it is also undeniable that, when players bonded like they did in the 1960s and 1970s over drinking sessions, they reached more finals and qualified for more competitions than the current generation of athletes.

It says something about the love and respect for Jimmy Johnstone, or maybe about the Scottish psyche, that despite being at Celtic from 1961 to 1975, winning the European Cup, nine successive league titles, four Scottish Cup and five League Cup titles, scoring 130 goals in 515 appearances, finishing runner-up in a further European Cup final in 1970, the infamy of the Largs boat incident endures. Johnstone was far from perfect and, in some ways, this made him even profoundly beloved.

The common man related to him, perhaps seeing something of themselves in his frailties. They could envisage being as daft when drunk and behaving in as disorderly and boisterous a way. Only a few could dream of being able to play football like him.

Disappointed by the media’s broadly hostile reaction to his rowing expedition, Jinky produced one of his best performances for Scotland that weekend, giving England’s Emlyn Hughes a torrid time. At the end of their 2–0 win, the players did a lap of honour – and Jinky duly threw two fingers up at the press box.

The esteemed journalist, Hugh McIlvanney, summed the whole incident up perfectly: ‘It was probably quite characteristic of Jimmy that he went through all that nonsense on the Ayrshire coast then proceeded to perform like an inspired demon against England at Hampden’.

Players like Jimmy Johnstone remind us of a time when footballers weren’t robots and drilled monkeys – they were men of the people; imperfect, normal men who conquered the improbable. They made mistakes, they achieved greatness and, most magically, they walked among us.

Exhibit 8

James McFadden and the Missed Flight

The happiness James McFadden bestowed upon the nation is, frankly, difficult to quantify. He brought sunshine and hope to minds lost in the dark psychosis of Scottish football’s hurt locker. He was an exceptional footballer who also brought an emotional authenticity, which connected to the hearts and minds of an increasingly disenfranchised Tartan Army. Here was someone who showed an early capacity for lager bampotry, a tendency to lose it with a late tackle and the knack for scoring an opportunistic wonder goal.

McFadden’s game was built upon incisiveness and intelligence. His gallus swagger was coupled with a precocious impatience for those who weren’t on the same wavelength. He also had an eye for a pass and an innate habit of ‘knowing where the goal was’ and yet, in terms of pace and movement, he had about as much mobility as the Duke of Wellington’s statue.

There were many moments in his forty-eight international caps and fifteen goals where McFadden showed his class. In the first leg of a play-off for the 2004 European Championships against the Netherlands in November 2003, he scored the only goal in a 1–0 victory. And who could forget that wonderful night in September 2007 when his effort from thirty-five yards out flew into the net and propelled Scotland to victory over the 2006 World Cup runners-up?

Headlines the next day proclaimed it to be ‘the shot that echoed around the world’. There were also dramatic goals against Lithuania and Ukraine in the same year.

Every time Scotland won a free-kick within thirty-five yards of the opposition’s goal, there was an air of legitimate expectation around the stadium. When ‘Faddy’ was at his peak, free-kicks were as good as penalties. He was that good. He was a match-winner, plain and simple.

McFadden was also part of the Scotland side that went into the final game of the 2008 European Championships campaign with all to play for. Standing in their way? The reigning world champions, Italy. In the end, the Scots lost narrowly, going down 2-1 thanks to an injury time winner that stemmed from a free-kick that never should have been awarded.

McFadden had endeared himself to the Tartan Army from the outset after ‘missing a flight’ in Hong Kong following his international debut under the maligned Berti Vogts. ‘Missing a flight’, for what it’s worth, is a euphemism for a youngster being let off the leash, a long way from home. Initially, it was reported he had slept in. It was later suggested he had gone AWOL. In the end, it was agreed he was on the ubiquitous boozy night out with teammates and ‘got lost’. The long and the short of it is: he missed the flight.

As far as managers or SFA blazers are concerned, ‘missing a flight’ is a monumental error. However, if you have a bit of footballing élan and are also a demon in the swally stakes, you’re loved by the fans. ‘Missing a flight’ ensures lifelong membership into the booze-bag hall of fame.

The latter stage of McFadden’s career was blighted by a cruciate knee ligament injury that deprived him the opportunity of unleashing his true potential at the highest level, on a platform it deserved. McFadden was the personification of the silky player with a lightning fast creative mind but who was, in terms of physical pace, as slow as a week in the jail. He was a player who had the toolkit to become world-class. In truth, he should’ve become one of the finest footballers the country has ever produced but a combination of bad luck, bad timing and, arguably, bad decision-making curbed what should’ve been a golden career.

After a short spell at Sunderland – his third English side – McFadden appeared happy and settled as a player-coach and assistant manager at the club where it all began for him, Motherwell. He was keeping fit, training with the youth team and made sporadic appearances to cover for the Motherwell first team when the squad was thin on the ground. He became a free agent after leaving the Fir Park side and, after training with his Everton teammate and then Queen of the South manager, Gary Naysmith, was offered a short contract with the ‘Doonhamers’. When Alex McLeish became Scotland manager in March 2018, he named McFadden as one of assistant coaches.

More recently, he has been a regular pundit on BBC Radio Scotland football shows and has proven to be a natural conversationalist with a sharp and eloquent voice. As long as international football exists, there will always be a place at any radio station in Scotland for James McFadden to come in and have a chat. Unlike his self-belief on the park, off the park, he is modest about his achievements and claims if he had played one game for Scotland it would’ve been enough. To play forty-eight? A dream come true.

James McFadden was a mercurial talent with the ability to leave fans spellbound. He was two caps short of the SFA Scottish Hall of Fame, so his inclusion to the alternative museum is a ‘thank you’ from the fans for his efforts – and, of course, for that one night in Paris.

Exhibit 9

Willie Johnston’s Prescription

Football can be ruthlessly vindictive.

Willie Johnston travelled to the World Cup in Argentina in 1978 playing the best football of his career for West Bromwich Albion. Weeks later, he returned like a pantomime Pablo Escobar, his reputation in tatters after failing a drugs test at the tournament.

He will be forever entwined into the fabric of Scottish football history, harshly judged by those who would say there’s no smoke without fire, and that an innocent mistake is a mistake nonetheless. The Scottish psyche can be malicious at times, delighting in witnessing people enduring misfortune. It often seems that we love to see someone in the public eye getting caught out and revel in watching their life unravel.

In 1757, the esteemed Scottish philosopher David Hume wrote Four Dissertations