Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

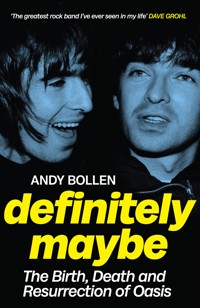

Ride the Oasis rollercoaster ahead of Live '25. Oasis were Artful Dodgers from a housing estate who created stadium anthems that connected with millions. They became the band of the people by giving the people what they wanted: rock 'n' roll. Ahead of the Live '25 Tour, Definitely Maybe offers a unique take on their story. The euphoric highs, spectacular implosions, chaos, excesses and sibling rivalry. How the Gallagher brothers captured the zeitgeist of the 1990s by embodying the hopes and frustrations of a disillusioned generation. In a rollercoaster ride from their humble beginnings in Manchester through Britpop jousts with Blur and legendary shows at Knebworth, Andy Bollen unveils how their relentless drive, swagger, Irish blood and English heart left an indelible mark on pop history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 408

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DEFINITELY MAYBE

A note on the author

Andy Bollen was involved in music from the age of fourteen. He worked in record shops, he was a DJ and he toured with Nirvana. He has written about football, sports and politics, as well as being a newspaper columnist and comedy writer for BBC TV and radio. His music books include Nirvana: A Tour Diary and Labelled with Love: A History of the World in Your Record Collection.

Also by the author

Nirvana: A Tour Diary

Sandy Trout: The Memoir

A History of Scottish Football in 100 Objects

Fierce Genius: Cruyff’s Year at Feyenoord

A History of European Football in 100 Objects

The Number 10: More Than a Number, More Than a Shirt

Labelled with Love: A History of the World in Your Record Collection

Classic Derbies and Epic Rivalries: A Journey Through the World’s Most

Captivating Football Clashes

DEFINITELY MAYBE

The Birth, Death and Resurrection of Oasis

ANDY BOLLEN

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

1

Copyright © Andy Bollen, 2025

The right of Andy Bollen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

ISBN 978 1 84697 719 0

eBook ISBN 978 1 78885 801 4

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf, S.p.A.

To Sharon Murray (née Galway)1965–2024

‘I live for now, not for what happens after I die. I’m going to hell, not heaven. The devil has all the good gear. What’s God got? The Inspiral Carpets and nuns.’

— Liam Gallagher

‘What inspires me to write music? It’s just what I do. And I’m fucking brilliant at it.’

— Noel Gallagher

‘Those two guys are arguably the best comedians Britain ever produced. It’s annoying how fucking funny they are.’

— Bill Burr

Contents

Preface

1. Knebworth & the Media Turn 1

2. King Tut’s 31.5.93 (Part 1)

3. Birth of Britpop, the Creative Evolution of a Scene

4. Back to the Future

5. Noel Joins, Made in Manchester & Top of the Pops

6. Marcus Russell & The Deal

7. King Tut’s 31.5.93 (Part 2)

8. Creation: How Does It Feel?

9. The Lost Art of A&R

10. Gestation Period

11. Definitely Not, Amsterdam, The Word & NME

12. T in the Park

13. King Tut’s 31.5.93 (Part 3)

14. Promo, Football & Northern Soul

15.Definitely Maybe, Review, Impact & Aftermath

16. ‘Live Forever’, White Heat, Wall of Sound

17. Death in Vegas

18. Noel Leaves the Band & ‘Whatever’

19. King Tut’s 31.5.93 (Part 4)

20. What’s the Story . . . with the Drummer?

21. Blur: What’s Their Story?

22.Morning Glory v. The Great Escape

23. King Tut’s 31.5.93 (Part 5)

24. Macca & Woolworths

25. Sibling Rivalry, Made in Manchester & Breaking America

26. Irish Blood, English Heart

27. King Tut’s 31.5.93 (Part 6)

28.Rashomon Ruffians

29. And in the End . . . Legacy

30. We Are the Resurrection & Reunion

Acknowledgements

Preface

With Oasis, it is impossible to pen the standard rock book. They are a band like no other and their life a drink-anddrug-fuelled working-class fairytale. Forget any high-brow deconstruction of song structure, lyrical meaning or a detailed search for the artist’s inner soul. No introverted navel-gazing or emotional heartache. No talk of vintage guitars and amplifiers or recording techniques and studio consoles. Oasis – both the band and their music – did not exist in a context of ambiguity. That’s not them. However, if you want a band willing to run into a burning building to get you out, or maybe fit a kitchen in a day, they’re your guys – or at least four of them are. They are a band best listened to loud and late, wham-bam thank you ma’am. The message is clear. Let’s go for it, party hard, forget the misery and bleakness of reality and turn it up.

I was there on that quiet Bank Holiday Monday evening in May 1993 when Alan McGee of Creation Records offered Oasis a record deal in King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut, Glasgow. My friend Ross and I were bored and remembered our pal, Derek McKee, DD, was playing in King Tut’s and put us on the guest list. I was an eye-witness to something unspectacular which proved to be one of the most significant moments in British music history. I thought Oasis were alright and couldn’t believe how animated Alan McGee became while watching them. During one particular song, he jumped with excitement as the lead guitarist played a solo. I eventually saw what McGee did and knew if I remained patient enough, the lads from Burnage would eventually return to the well.

I’ve watched their incredible triumphs and spectacular disasters from the moment they caught Alan McGee’s eye in King Tut’s to T in the Park and Knebworth. Their meteoric rise to fame, explosive fallouts and those key moments where it went spectacularly wrong. Not just slightly wrong but the musical equivalent of a friendly-fire attack, a self-inflicted omnishambles of enormous proportions. This was a band encouraged to be themselves, to bring excess and disorder, and they delivered. Yet when the elements were stable, and they kept it together, Oasis played groundbreaking shows.

I grew to respect Oasis. As they developed and bloomed into this globally famous and successful band, I looked on with pride at every achievement, every obstacle, the first TV appearance, their first single, like a nervous uncle. How uncool is that?

I’ve walked around shaking my head in disbelief for over three decades at their music’s inconceivable impact on so many people. Every time I see Liam in the news, even now, I can’t believe he’s the same guy I saw on stage that night. When I watch Noel chat on a BBC4 documentary about Britpop, I smile. I bought into their story. I saw behind the façade and sensed the vulnerability under the bravado, the five working-class lads from a housing estate, the lucky guys who made the grade.

It turned out Oasis had songs, and songs are important to us: they are our lifelong friends, as constant as the stars. Here was a band capable of producing songs like ‘Live Forever’, ‘Don’t Look Back In Anger’ and ‘Wonderwall’. There was sensitivity, but it was mixed with volatility, frustration and passion. Oasis not only had songs, they had classics that connected across a huge demographic. At times this does read like a surreal fairytale. The concept of this seemingly rough-andready band playing a random gig in Glasgow after acting on a casual invite from a mate and ending up with a record deal and global success is extraordinary. That didn’t happen any more, did it? In my experience record deals were the result of months, sometimes years, of chasing, of hard graft.

What McGee witnessed did not register with me. I was standing beside him. He was bouncing off me. Oasis played four ordinary songs and McGee was drunk and high (by his own admission, not mine). Speaking to the Guardian in 1993, on the tenth anniversary of Creation Records, Alan McGee was already smitten with the band’s demo: ‘The music is a cross between The Kinks, Stone Roses and The Who, and the cover of this tape, which is incredibly rare, only ten ever made, is important because it’s a Union Jack going down the toilet. That sums up our country at the moment. I don’t want to herald them too much, but they’re already one of my favourite groups. Seeing them is what seeing the Stones must have been like in the early days. Brutal, exciting, arrogant.’

Time has shown how McGee called it right. He had an eye for the shape and sound of a band. The look, the dynamic. I thought they were another baggy Manchester band. And although, for the opening act in a four-band bill, they were loud, I could never see it becoming a pivotal moment in British rock and pop history. One thing is undeniably true: at that moment McGee was far better at his job than Oasis were at theirs.

The rumours about Oasis and McGee at King Tut’s spread like wildfire across the city. No one in their right mind believed he’d offered this band a deal without knowing anything about them. Yet, according to McGee, it was sheer luck. It was a Bank Holiday and he thought the venue would be closing earlier than usual. His friend was also in one of the support bands so he thought he’d show up unannounced and surprise her. That’s how he accidentally caught Oasis.

While everyone scratched their heads and got on with life, Oasis were uncharacteristically off-radar, keeping quiet, recording, rehearsing and getting it together. Many assumed their classic debut album Definitely Maybe was an effortless project. It was far from it. Noel, Alan McGee and their manager Marcus Russell found it a stressful experience. They got it right eventually by doing what they did best, recording live as a group. ‘The demos Noel had given me were better than the studio recordings,’ McGee says in his autobiography. ‘They were trying to record the instruments separately, something that never works for our bands. It was another of our links to the 1960s; our bands worked best when recorded live.’

Despite splitting in August 2009, Oasis still had this lingering aura. It turned out their music was generational. The kids of the original fans grew up loving the songs. Oasis had enormous TikTok and Spotify figures. When it was announced in August 2024 that they intended to get back together, the world went mad. On Saturday 31 August 2024, tickets went on sale and Oasis officially broke the internet.

This book tries to understand how it panned out from that night in May 1993 in King Tut’s by leading up to the night and looking at those behind the band who steered their career, from record deals to developing their stagecraft. We look at the musical backdrop of the time and discuss what drove the band, what made them tick and what pushed them on to become one of the biggest bands in the world. We also try to understand why their legacy is such that after witnessing them live, Dave Grohl said: ‘That’s the greatest rock band I’ve ever seen in my life.’

11 August 1996: Set List

The Swamp Song

Columbia

Acquiesce

Supersonic

Hello

Some Might Say

Roll With It

Slide Away

Morning Glory

Round Are Way (ending with Up In The Sky)

Cigarettes & Alcohol

Whatever (Octopus’s Garden at the end)

Cast No Shadow

Wonderwall

The Masterplan

Don’t Look Back In Anger

My Big Mouth

It’s Gettin’ Better (Man!!)

Live Forever

Encore

Champagne Supernova (with John Squire)

I Am The Walrus

1

Knebworth & the Media Turn

The bass drum hits you like a cannonball to the solar plexus. The drum tech is over-eager. He’s out of time with the pre-gig music playing through the PA. The stinging orange smoke catches your throat. You feel like you’re an extra in a Vietnam movie. The scene shifts to a slow-motion shot. Events become confused. It all starts to become surreal. Every movement and thought process is framed, like a jarring reel-to-reel in a movie projector. Sky becomes ground. Ground becomes sky. The horizon changes and is blocked by a mammoth electric pylon. There’s something bizarre but enjoyable playing with and mixing up your senses.

Distinctive smells: the countryside, the stink of diesel, fried onions. Electricity. There’s a deep, powerful humming of generators and seismic vibrations. The carnival’s in town. Guitar music on a loop; playing backwards. Booker T’s ‘Green Onions’. Booker T frying green onions. Beautiful girls in denim shorts run with impractically attired men, plastic Mods. Onions, fried onions. A moment caught in time, a photograph, a snapshot, frozen forever. You immediately sense its significance; this is something you will always remember. The distinct noise of huge helicopter blades, whip-crack-thud-whip-crack-thud, pound directly above you. The sound is in stark contrast to the motion; you smile at the stylish ease and grace, the precision of the engineering of the helicopter itself. Leonardo da Vinci was some man. Then you catch a glimpse. Yes, it’s them, they’re only fifty feet above you. There you see the unmistakable faces of Oasis peering down. You can see them point and shake their heads and see the genuine concern on their faces. They are worried about your predicament. Don’t be. We will see you on the other side, brother. Sooner than you think.

Hours later, and with only a few feet of movement in the queue, the fifth band are on. The band in the chopper were correct to be concerned. In a few hours, to huge applause and a whirling engulfing cacophony, Oasis stomp on stage, and you can hear the noise coming through the trees. You’re stuck on a tiny country road, in a traffic jam to end all traffic jams. The only thing you can see for miles and miles are cars. The best new band in the world were playing through the trees in a field and, for many, this queue was the story of August 1996, when Oasis played at Knebworth.

Knebworth was more synonymous with major label artists and often disdainfully referred to as Knobworth thanks to the acts who played there. It was a festival for those who moved millions of albums, a vacuous, hubristic statement. For some reason, there was an establishment acceptance that to play in the shadow of Knebworth House out across the estate to thousands of fans was an achievement. A field of dreams for former public schoolboys and now music business bosses, basking in the glory of their charges. A self-indulgent folly for millionaire rock stars, flying in for the open-air rock concert and ticking every sorry cliché in the book along the way. But then Oasis played there. It didn’t seem so bad.

Many fine bands have played Knebworth but for every Rolling Stones, I’ll give you Queen. For every Who gig, I’ll talk about Genesis. For every Devo show, I’ll ask you about Jefferson Starship. There’s a peculiar music industry doff of the cap to those who make it and find themselves playing there. So, take a bow, Santana, Status Quo, The Darkness and so many more.

In May 1996, 2.6m applications were made for the 250,000 available tickets. Blenheim Palace and Castle Donington had been considered before Marcus Russell decided Knebworth was the best option from the fans’ point of view. Most music fans were miffed when it was announced Oasis, a Creation band, were to play there. When I heard there was a guest list of 7,000 and an individual trailer for each band member I sensed that something felt wrong. And that was before I heard security was so tight the man who offered them a recording contract in a club in Glasgow less than three years earlier took three attempts to get in to see his band’s crowning glory.

Joining the band, and the quarter of a million who assembled for the two shows, was a specially selected mix of dance and rock acts. Bands who would keep the party going nicely till the kings of Britpop strolled on stage. Playing the first gig, on 10 August, were Ocean Colour Scene, Manic Street Preachers, The Bootleg Beatles, The Chemical Brothers and The Prodigy. The second gig had Cast, Dreadzone, Kula Shaker, Manic Street Preachers and The Charlatans (who had lost keyboard player Rob Collins a few weeks earlier in a car accident). Admittedly, these bands were an improvement on Knebworth’s usual major-label buy-on bands and heavy metal groups. It was an unusual decision to play there but it was chosen, despite the traffic jams getting in and out, as it was the most realistic venue that could come even close to satisfying ticket demand; plus, it was also one which matched the band’s uncompromising ambition.

Knebworth is a vast, sprawling estate near Stevenage in rural Hertfordshire. Historically, it was the perfect place for the Rolling Stones, Queen and Led Zeppelin to rock out. Yet Oasis naturally embraced the landmark gigs with their accustomed haughtiness, shrugging their shoulders as if to say, ‘Well, what did you expect?’ Now Oasis were like them, behemoths – giants of rock. This was the key. This was the journey; from King Tut’s to Knebworth, in three years. With a colossal, towering PA and gigantic video screens, nothing matched or beat the sheer size and scale of the Oasis shows. To be fair to the band, it was only £25 a ticket, not bad considering the number of decent bands on the bill. Touts could squeeze you in for anything between £250 and £300, and that’s what it cost those city types beside friends at the gig. You even got to see a terrific fireworks display at the end too. (More about that later.)

There was nowhere else big enough for Oasis, and it was seen by McGee, the band and Marcus Russell as a true statement of the band’s popularity at that specific moment. It also feels symbolic that Oasis had reached their peak by the time they played Knebworth. Perhaps it was the scale and magnitude of the event. If it was a movie (a documentary movie was released twenty-five years later in 2021), it would be the perfect end, chapter over. If it was my band, I’d have walked away from it at its peak. Say thanks for the ride, but we can’t beat this. We’re quitting while we’re ahead. Two groundbreaking albums and two landmark live shows. ‘It’s over, thank you Knebworth.’ I wasn’t alone in thinking this. Guitarist Bonehead told the Guardian in 2009: ‘I always thought we should have bowed out after the second night at Knebworth.’ Then again, Noel was under pressure with the third album already written, and a recording contract to honour.

As the money came rolling in, Oasis were enjoying themselves. Not exactly seduced by the fame and fortune, but certainly living it large. You’ve got to accept that guys who grew up where they did, who had a tough time, are going to flaunt it a bit. Why should we be modest? We deserve it. When Noel became famous and made some real money, he bought his house in Primrose Hill and christened it ‘Supernova Heights’. And until 1999 it was infamous for its bacchanalian excesses. He then went on to buy even bigger and better houses in the country and abroad and spent freely on the cars, guitars and all the usual trappings. You could always tell Noel was a working-class hero because one of the first moves he made when his ship came in was to have his teeth done. And they are tremendous teeth. He suits them. He doesn’t have that look some celebs have when they get new teeth and come back from Turkey looking like they’re breaking gnashers in for a horse.

Oasis played the gigs with unwavering assurance and confidence. Their assuredness only served to make it appear that playing these career-defining gigs was an everyday occurrence. Nonchalance and self-belief were the order of the day. The band and management’s decision to play Knebworth split Creation staff. Some were unhappy about the gig’s corporate nature and the band’s change. To some, it was a crass corporate rock event, a million miles away from the spirit of what the true indie ideal was about. Others remained more pragmatic, thinking if it wasn’t for the Sony money they’d be dead and buried by now. For many, the Knebworth shows were a step too far, especially if witnessed as part of Creation’s natural arc. You go from the beginning, see Alan McGee’s journey from The Living Room, those first club nights and gigs above pubs in London, from The Legend! to The Television Personalities, from Primal Scream to My Bloody Valentine, from Teenage Fanclub to Oasis – the continuation of a sequence of remarkable events.

By August 1996, millions wanted to see Oasis. Some at the label also took a more practical point of view: this was the only kind of show that could satisfy demand by playing to 250,000 people over two days. With demand for tickets hitting the 3-million mark, the band would’ve had to play twenty-four separate shows at Knebworth to satisfy all those who desperately wanted to see them. Having reached the pinnacle, the subsequent problem that inevitably followed for the band, and Noel in particular, was – where do we go now? And how could he continue writing exciting songs with an edge, when they were so outrageously rich and successful?

Noel had written most of the songs on Definitely Maybe while working in a building site storeroom or unemployed, in his early to mid-twenties. That’s what gave them such vitality and desire. How do you write songs that connect with your audience when you are beyond wealthy, and worse still, now enjoy telling people how rich and successful you are by rubbing it in their faces? That’s how it felt in 1996. Noel in particular, once with a keen internal barometer of how to keep the man on the street onside, was acting way above his station; it had gone straight to their heads. They were heading for a fall.

Always clever enough to carry off playing the part of the cheeky rock star, Noel wouldn’t take those who supported the band for granted. He was always aware the fans put the band up there. He’d always kept it real, playing it perfectly, part confidence and part charm, but he was now turning into a caricature of a Loadsamoney type. The drugs do work, allegedly.

The show at Knebworth was as much about the band’s celebrity status as it was about the music. Oasis had reached this weird place in society where everybody, their mum and their granny were aware of them. They were hanging out with film stars, supermodels and all kinds of famous people and were protected by a ring of security more fitting for a visiting head of state.

Those present spoke about two things. The backstage marquees bigger than festival tents. No one’s arguing with the success and how much the band deserved it considering where they started from. What their fans and Creation staff who put in the hours working for them couldn’t buy into was how much this obsession with celebrity turned their heads. You also have to remember this feeds both ways. They were the band of the moment and Noel and Liam were the men to be seen with. They had moved on from being favourites of the NME and Melody Maker and were now prime targets of The Sun and The News of the World (the latter now gone; how sad, oh my).

The second issue raised was the fireworks. How it felt there was something symbolic afoot as they watched explosions and rockets crack and flash across the sky. Powerful blasts and cannon fire everywhere, whizzing, banging, snapping, hissing, a circling, cascading cacophony, a crescendo of noise. This sonic spectacle felt like a closing chapter and out of place for an Oasis gig. While promoting his autobiography around 2013, Alan McGee mentioned the fireworks and that moment too. It had a significant effect on him; it was out of character, maybe the noise shook him and made him realise he was growing apart from the band.

The tabloids now lauded Oasis. They talked up the shows. Suddenly the band had transcended from being a Manchester band with a couple of decent singles into this entity or commodity who shocked and thrilled with their behaviour. The press excitedly proclaimed that Knebworth was the fastest sell-out in history. Some papers decided to go as far as calling it the gig of the century. I would have plumped for Led Zep at Madison Square Garden, New York in 1973 or The Beatles at Shea Stadium or Candlestick Park or a random gig by the Ramones in CBGB’s in the East Village. I have an A4 poster in a drawer promoting The Cramps and The Fall at Glasgow Tech in 1980, which always sounded like fun. (I was too young, aged 13-ish at the time, but the idea of seeing Kristy Marlana Wallace, AKA Poison Ivy, in the flesh would have been too much to take.) What about Jimi Hendrix at the Isle of Wight or Woodstock? The Who live at Leeds? Nirvana at Reading in 1991, Killing Joke at Glasgow Barrowland in 1985 or how about Primal Scream at Hanger 13, Ayr Pavilion, 1993? I could happily do this all day.

The reality was that Oasis had become far too big. They towered over Creation and suffocated the development of bands attempting to come through. Creation had now become Oasis. The major problem was that the band’s popularity had grown exponentially. Those in favour of them playing Knebworth could say, well Oasis are produced and distributed by an indie in the UK, but the truth is they were seen by most at Creation as a worldwide Sony band.

From performing as The Rain, then changing their name to Oasis, then Noel joining and their relentless rehearsals in The Boardwalk, the Oasis story is genuinely mind-blowing. The same band had gone on this rare and remarkable odyssey. From being another average Manchester-sounding band with a soft spot for The Stone Roses to walking onto that stage at Knebworth. (There was a symbolic moment, a passing of the torch, as the band were joined onstage by The Stone Roses guitarist John Squire to play ‘Champagne Supernova’ during the encore.) The same band I was nonplussed about at King Tut’s were playing Knebworth. They were now one of the most famous rock bands the UK ever produced and in the process went on to sell well over 22 million copies of (What’s The Story) Morning Glory?

These sales figures made it tough for any artist to remain level-headed and the press quickly flipped, demonising Oasis and ridiculing their wealth. Noel was an easy target with his house ‘Supernova Heights’, his chocolate-brown Rolls-Royce – which he couldn’t drive – and his newly immaculate teeth. At first, everyone was rooting for the band, but once they achieved so much success, it seemed that they rounded on them. The tabloids were brutal. But the people they were attacking were from Burnage. They didn’t give a toss.

Where were the reports in the press about Blur’s country houses and wealth? A competent tabloid editor can twist, manipulate and nuance anything they want to get their side of the story across; after all, it’s their job. Perhaps Oasis liked to flaunt it whereas Blur were a little cuter about it. The line always read something like, ‘Well, they’re working-class northerners who’ve got lucky and can’t stop bragging about their good fortune and wealth.’ The situation was polarised and oversimplified and on many occasions inaccurate. Blur were chess-playing, cricket and cheese-loving cads. They weren’t. Oasis fans wanted the shocking, lurid leanings of The Sun and The Mirror.

The fact that Oasis made it so big – and connected with the masses – still takes me by surprise. I never envisaged such a vast swathe of the general public looking to Oasis and tuning into their music. They appeared accessible, looked like the common man, acted like the common man and spoke for the common man, so when the common man thought they were getting too big for their boots they enjoyed seeing them self-destruct, they relished seeing Liam lose teeth after the nightclub fracas in Germany. There was a definite change towards them, slowly controlled by the music press and the media in general. To the newspapers, they were a busted flush. From 1994 to 1997 they had their fun with the band and then moved on. Apart from the Rolling Stones, I can’t think of a band before or since who generated so many column inches.

The continued concept and ploy of ‘any publicity is good publicity’ had eroded and diluted the public’s opinion of the band, and Liam in particular. Now it was so clichéd and predictable. Liam would act up, retaliate first, then strike out without thinking. It was hardly news if everyone was waiting for it to happen. There they were, splashed across the newspapers, in another drunken brawl, getting into slanging matches with the paparazzi. Liam, especially, always took the bait. No matter how tough it was for him to turn the other cheek, the reporters and photographers knew how easy it was to goad Liam into a reaction and provoke him into flying off the handle. What if Liam was in on it and knew that, say, if he headbutted a Sun photographer, the free publicity would secure a sell-out show and another 5,000 albums that week? All by getting his brawling mug on the front cover of the tabloids.

Despite not knowing it at the time, Knebworth, perhaps by default, was the end of a chapter and the end of the Oasis we’d grown to love. Or at least it was the end of the beginning. Playing there was a statement. In playing to such colossal crowds, Oasis were saying, OK, look at all these people who are into us. Let’s see if we can get the same reaction in Rio, Barcelona or Sydney. Creation may have enjoyed the ride up until now but Sony must have been thrilled.

Of all the goings on, the debauchery, the coke, my abiding memory of the Knebworth shows were those reports of Liam driving about the VIP area in a golf buggy trying to hit famous people, including Ant and Dec. Sounds too funny to be true. It appears it was true. Here’s what caterer Alex Vooght, speaking in the documentary, Oasis Knebworth 1996, recalls: ‘I remember standing at the front of the marquee I was working in, and Liam had spotted Ant and Dec. He clocked them and drove straight for them in his golf buggy, and they had to dive out of the way like cartoon characters.’

2

King Tut’s 31.5.93 (Part 1)

‘One Night in May 1993’ was one of many titles for this book. Here’s what I wrote in my diary:

Boyfriend/18 Wheeler gig, 31 May 1993.

Standing beside Alan McGee, he was excited, practically going nuts, animated watching one of the support bands, a Manchester band called Oasis. They were loud, a bit aggressive, and angry, the singer and the guitarist stood out. The frontman snarled, had that nasal tone and sounded like a Stone Roses/Manchester-type band. They were workmanlike, tense and angry, but nothing too remarkable. They were very loud. Their songs were long. They slaughtered ‘I Am The Walrus’.

Clearly, my A&R skills are rusty. I kept a diary at this time because I was involved in bands. It seemed important then, to keep notes on what was happening with other bands and gigs I’d been to. With hindsight, I could’ve changed it and eulogised about witnessing the future of rock ’n’ roll in Oasis and predicted they would go on to play iconic gigs, write generation-defining songs and make classic albums that would resonate through the ages. In the brief passage, I repeat two words twice, loud and angry, and that’s how I would describe Oasis on that night. (I also repeat Manchester; make of that what you will.) Later, downstairs, when asked at the bar what had just happened with Oasis, I was mocked when I said Alan McGee had just offered them a deal. I saw him and the guitarist shake hands on it. I wouldn’t have offered them a pint never mind a recording contract. I honestly felt a bit sorry for them; to me they sounded a bit dated.

People constantly ask me what it was like to have been there. What were Oasis like? The clearest and most consistent memory I have about one of the most talked of moments in UK rock ’n’ roll history was how unremarkable it was. I usually smile and shake my head when I think about it. I remember a rigid, workmanlike band on stage. They were well-drilled but performed like a band who rehearsed far more than they gigged. They needed to relax more on stage. Sometimes it’s easy to rehearse the soul out of a song. One gig is better than three rehearsals.

There was little interaction and what there was came from the lead guitarist. He was the boss. It’s outlandish to think they became this major sensation. That’s the real Oasis story. How a band could go from the one we witnessed in May 1993 and transform into a group that would play such a significant part musically and culturally. They became central figures in politics, football, fashion and the whole phenomenon of Britpop. I normally finish by saying McGee was either a genius or lucky. In truth, probably a bit of both.

It was so unspectacular. There was no way you could envisage it becoming such an iconic moment. I was not thinking, wow, in decades to come, millions will regard this a momentous and significant night. It was anything but. We were hanging out at a gig waiting to watch our mate’s band and then friends of support band Sister Lovers ambled on stage and played loud, long songs.

The night Alan McGee offered Oasis a deal at King Tut’s has become fabled. There’s a self-perpetuating aura around this evening in 1993. It’s now one of those nights that has drunkenly meandered into the realms of mythology. It’s surreal to consider it’s up there with the most talked about moments in rock and pop history. That’s a lofty position when considering the many noteworthy moments rock ’n’ roll has thrown up. Is it up there with 9 February 1964 when The Beatles played the Ed Sullivan Show? Dylan being called a Judas at Manchester Free Trade Hall in 1966 for going electric or the Sex Pistols swearing on the Bill Grundy Show? Is Oasis at King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut that momentous? The gig is now afforded a similar eminence. But its ordinariness continues to amaze me.

The myths and rumours of the night have grown to such an extent that if you believed them, Oasis would’ve been playing to a crowd the size of Knebworth. Other than the main players in the drama, the bands, crew and staff, there were around fourteen people present to watch the band perform. I know, because it was one of the lowest crowds I’d ever seen at King Tut’s. It was so quiet you could do a rough head count. The history books and detailed, exhaustive research have given us a figure of sixty-nine paying punters in total, for the night. I’ve played sold-out shows at King Tut’s and it’s a beast of a place to perform in when it’s full. When filled to its 300-capacity, it’s a hot and lively venue. That night, I was surprised at how quiet it was.

For the romantic dreamers among us, this only added to the band’s enduring appeal. This story, from near-empty venue to being lauded by millions. That figure of sixty-nine doesn’t include the guest list, which wouldn’t be too big if the crowd was so small. But, remember, they weren’t upstairs at the venue. When Oasis played, most were still downstairs in the bar. But that’s OK. That’s what happens when a night like this occurs. Those present stay quiet, while those who stayed at home watching TV get to have an opinion and lie about being there. Those who were nowhere near King Tut’s add their partial truth to the legend and, by the time the anecdote reaches you, Oasis were about to bomb the venue down if they didn’t get to play and when they did, they performed like rock messiahs. They were Led Zep, Bowie and The Beatles but with bigger and bushier eyebrows. No, I’m sorry, they weren’t.

I could name most of the people there. Alan McGee and his sister, Susan, were to my left. Eugene Kelly, to my right. Then behind us, my friends Ross Clark and Derek McKee and a few other guys from Boyfriend. There was also a Japanese couple, friends of 18 Wheeler, who I remember thinking, poor kids, coming so far to see this band on a Monday night in Glasgow. Paul Cardow and Murray Webster were there, members from the other bands were scattered around, though not many. Most of the bands playing were in the dressing room tanking into their rider or downstairs chatting in the main bar. There were two or three from the Oasis crowd dotted around the seating at the back behind the mixing desk and on the bench down the side of the venue. There were staff, busy running around. I see Frankie, Gerry Love’s girlfriend at the time, working at the upstairs bar, and William Fyfe the bar manager, who was busy earlier keeping an eye on the Manchester crew while working betweeen the live venue and the downstairs bar. You get the idea. It wasn’t lunchtime in the Cavern in 1962.

3

Birth of Britpop, the CreativeEvolution of a Scene

It’s a wet Thursday evening in March 1991. Aren’t they always? I’m heading to London on the overnight bus. I find my Tufty Club badge, which I thought I’d lost in the lining of my biker jacket. It’s a sign. It’s fallen through a small hole in the pocket. Fortunate moments occur when I wear it. ‘Lucky Badges’ became a song that never saw the light of day with the opening line: sometimes I feel like I’ve fallen through a hole in my pocket. The Lucky Badges were also the name of a fictional band in a short story I wrote at school. One teacher loved it and she sought me out to tell me. Ellen Hughes her name was – Mrs Hughes. It was someone in Nirvana who explained to me that, in America, a badge is called a pin.

Every time I wear the badge, it brings me luck and love. I’m visiting a friend who lives down in London. The original idea was to see Blur play at The Venue in New Cross, but my friend’s shifts get in the way. I’m befriended by Morag and Gill – because, I’m told much later, ‘You know how to wear a biker jacket and we love your Tufty Club badge.’ I’m still not entirely sure what knowing how to wear a jacket means but from the moment they got on the bus in Glasgow, we just clicked and got on immediately. They’re a cool mix of indie rockabilly with a slight edge of Goth. It turns out we share a few friends. We are acquainted with people from bands and have several mutual friends who attend the Glasgow School of Art. It’s a small world.

They share their considerable carry-out (booze bought from an off-licence) with me and because of roadworks the normal eight-hour journey becomes almost eleven hours. I know my friend was on his last nightshift and probably still sleeping, so I suggest we go and get a bit of breakfast from a greasy spoon. When I see how cheap it is, I insist on buying as I want to return their carry-out generosity. More coffees and teas are ordered and after a few hours of exchanging stories, addresses and phone numbers, it’s almost lunchtime, 12.30-ish, and now we aren’t hungry, we’re thirsty. Gill suggests we go to this cheap little boozer she knows with a marvellous jukebox, the name of which escapes me.

I can’t believe my luck, as if it’s another sign, and by one o’clock we were in this small place right across from where I was staying, close to Great Ormond Street. It was beside the Celtic Hotel on Guilford Street, at Russell Square. I remember it from an album cover by the Battlefield Band from my record shop days. I went over to check and my pal was sleeping. I could hear him snore and so I left my bag with a beautiful Irish nurse across the way who knew him. She kindly gave me a notebook and pen to leave him a note. If she wasn’t heading for duty she joked, she would’ve loved to come and join us. She loved the badge too.

I’m convinced back then people were warmer and nicer to each other, especially if you liked music. Few had a mobile phone and if they did, they were so big you would look like a total lunatic carrying it around, so no one bothered. It’s still 1991, remember, so we don’t have texts, or emails on our phones, no X (Twitter), WhatsApp, Facebook or TikTok. The internet had only just been invented. It was still two guys with electronic paper cups and a bit of fraying string between them but it was called the internet. If you were going to meet someone, you’d arrange to meet them at a given place and a certain time and wait till they showed up, and in the old days they usually did. This was a time before phone boxes became toilets or non-existent; instead, they were used as crucial modes of communication. So when someone gave you a phone number or an address, you wrote it down and kept in touch, maybe you even wrote a letter.

They, the girls, want to go to their friend’s place who they are staying with, get a sleep, change and head to this club above a pub, near the Post Office Tower, which, they excitedly explain to me, was run by Alan McGee years before. By now he was running a record label and dealing with Teenage Fanclub, My Bloody Valentine and Primal Scream. That always stayed in my mind. As if it was some kind of indie music shrine, or maybe a guarantee of a cool and tasteful indie night. He hadn’t been near the place for years. I can’t remember if it was the Adams Arms in Conway Street where the first Living Room club nights were held. But Alan’s presence or maybe the attitude of an upstairs night above a pub close to the Post Office Tower always reminded me of the seminal birth of Creation – and the opening titles of The Goodies.

The girls don’t make it to their friends: we all stay out. I get lazy, see a phone box and instead of running over the road, I wake up my friend who is knackered and content to let me do my own thing. Before we know it, we’re into happy hour, then the next thing it’s late and dark and we’re heading to this club. I’m in a small, tight club above a pub and something is happening. You can sense it. There’s a distinct look and sound, a nod to the classic Mod, R&B and 1960s garage rock. A cool club, full of people in bands, some who would eventually have a role in the Oasis story. Members of Blur and Ride casually mingle.

The place is packed to the rafters. There’s a Mod look and style to the fashion as if the kids have just jumped off their scooters. Smart jackets, striped T-shirts, tight-fitting tops, hipster trousers. Think pictures of The Who circa 1968. Crucially, however, it doesn’t feel like they’re trying too hard. There’s no snobbery. You would expect with everyone so cool and hip there would naturally be an element of exclusivity but it’s the opposite. It’s mainly full of music fans contributing, DJing, organising and running things, and punters who seem to love the music.

Each song powers through, the drumming has a driving backbeat. The girls are beautiful, cool, and some have beehives, wear miniskirts, bright colours, and sport high hemlines. There’s also a punk aspect to their fashion. The guys are in drainpipes and wearing Chelsea boots with their hair modelled into a Bobby Gillespie circa Primal Scream 1987 fringe. This is a scene. This is what it’s like to be at the start of something. Let’s bottle this. We could make a million. This could happen. The sounds are fantastic. They follow a direct line, there’s a natural flow as each song overlaps into the next. There’s music from one of my favourite eras, the 1960s. Garage, Mod and psychedelic punk pop. There’s The Yardbirds’ ‘Over, Under, Sideways, Down’ and then The Kinks’ ‘You Really Got Me’, then we’re off with The Kingsmen’s ‘Louis Louis’ and the hipsters and beatniks pick up the pace as The Litter’s ‘Action Woman’ and The Haunted’s ‘1-2-5’ kick in. Bam!!! There’s a Mod nod to Motown, with The Marvelettes singing ‘I’ll Keep Holding On’. There’s an energy, a happening feel. We move to northern soul and Betty Everett sings ‘Getting Mighty Crowded’, and it is; the place is jam-packed and musically it’s all converging and making perfect, rhapsodic sense.

Is this just a random group of cool young people coming together for a night out? Yes. But are they conscious of the fact they’re cultivating a scene? Is it a concerted effort or is it all happening naturally? Is this the beginning of a movement? Here in a small club, in London in 1991? I thought it was so cool, so hip, so bang on the money that I came out of my shell and danced to the bar. Two cider and blackcurrants for my friends and a Jack and Coke for the man who knows how to wear a biker jacket.

In a few months’ time, Nirvana, Sonic Youth, The Smashing Pumpkins and The Pixies were welcomed from the edges into the UK mainstream. Suddenly, having played small clubs across Europe to pockets of faithful fans, all these bands seemed to come through. Sonic Youth had been playing festival shows across Europe and had invited label mates Nirvana to tour with them. Then Nirvana played Reading in 1991; if you’d like to see it in action, this period is chronicled in Dave Markey’s movie 1991: The Year Punk Rock Broke. All these bands brought their brand of punk and independent music into the mix from across the Atlantic. Some thought they were far too commercial. I just thought they were professional, seemed well-managed and knew exactly what they were doing.

Pubs would open the dusty function suites upstairs and give small club nights a chance and soon there’d be nights on a Tuesday, Wednesday or Thursday and there was something of a backlash across London. In a few years, Blur were the first band to actively question the credibility of those same American bands. Albarn was especially vociferous around this time, although by 1997 he was more relaxed. He eventually embraced Graham Coxon’s love of lo-fi underground American bands like Pavement. Songs like ‘Beetlebum’ and ‘Song 2’ yielded hit singles and a return to form on their critically acclaimed album of the same year, Blur. But in 1991, he chose to champion British bands of the 1960s like The Kinks and The Small Faces and deliberately adopted a pro-British anti-grunge stance. Ironically, the friction created by the emergence of American bands acted as a catalyst to the UK music scene at the time.

In the same year, this time in December of 1991, on a Thursday, I was in a club called The Syndrome on Oxford Street. It was a similar gathering of hip bands and tasteful indie people. This time the music was more from British-based indie bands. The Television Personalities and tracks from My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless, which had come out around this time, were also playing. Again the vast majority of the sounds were based on garage punk and 1960s Mod groups.

Cool people, wearing cool jackets, with cool badges, and some are so cool that while the music is pumping they’re reading a Penguin classic; I can’t help but notice one coquettish hipster reading Virginia Woolf. A couple in front of me read a fanzine and I overhear them talking about Calvin Johnson of Olympia’s Beat Happening. They smile as I nod approval at mentions of Sub Pop and their chat about bands like Mudhoney and Nirvana. I was drummer of the band Captain America, and we had been invited to open for Nirvana on their Nevermind tour. We had just played the last night of the UK leg at Kilburn National. If I may be forgiven for a monumental piece of namedropping, by coincidence it was the end of tour party and we left a free bar and headed to this club. I was standing with my friends Kurt Cobain, Krist Novoselic and Dave Grohl.