Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

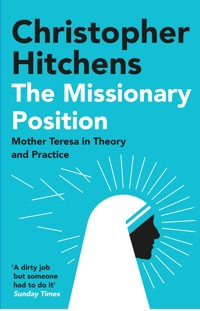

Recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, feted by politicians, the Church and the world's media, Mother Teresa of Calcutta appears to be on the fast track to sainthood. But what makes Mother Teresa so divine? In this frank and damning exposé of the Teresa cult, Hitchens details the nature and limits of one woman's mission to help the world's poor. He probes the source of the heroic status bestowed upon an Albanian nun whose only declared wish was to serve God. He asks whether Mother Teresa's good works answered any higher purpose than the need of the world's privileged to see someone, somewhere, doing something for the Third World. He unmasks pseudo-miracles, questions Mother Teresa's fitness to adjudicate on matters of sex and reproduction, and reports on a version of saintly ubiquity which affords genial relations with dictators, corrupt tycoons and convicted frauds. Is Mother Teresa merely an essential salve to the conscience of the rich West, or an expert PR machine for the Catholic Church? In its caustic iconoclasm and unsparing wit, The Missionary Position showcases the devastating effect of Hitchens' writing at its polemical best. A dirty job but someone had to do it. By the end of this elegantly written, brilliantly argued piece of polemic, it is not looking good for Mother Teresa. - Sunday Times

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 110

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS (1949–2011) was a contributing editor to Vanity Fair and a columnist for Slate. He was the author of numerous books, including works on Thomas Jefferson, George Orwell, Mother Teresa, Henry Kissinger and Bill and Hillary Clinton, as well as his international bestseller and National Book Award nominee, God Is Not Great. His memoir, Hitch-22, was nominated for the Orwell Prize and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

ALSO BY CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS

BOOKS

Hostage to History: Cyprus from the Ottomans to Kissinger

Blood, Class, and Nostalgia: Anglo-American Ironies

Imperial Spoils: The Curious Case of the Elgin Marbles

Why Orwell Matters

No One Left to Lie To: The Triangulations of William Jefferson Clinton

Letters to a Young Contrarian

The Trial of Henry Kissinger

Thomas Jefferson: Author of America

Thomas Paine’s “Rights of Man”: A Biography

god is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything

The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever

Hitch-22: A Memoir

Mortality

PAMPHLETS

Karl Marx and the Paris Commune

The Monarchy: A Critique of Britain’s Favorite Fetish

The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice

A Long Short War: The Postponed Liberation of Iraq

ESSAYS

Prepared for the Worst: Selected Essays and Minority Reports

For the Sake of Argument: Essays and Minority Reports

Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere

Love, Poverty and War: Journeys and Essays

Arguably: Essays

COLLABORATIONS

Callaghan: The Road to Number Ten (with Peter Kellner)

Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question

(with Edward Said)

When the Borders Bleed: The Struggle of the Kurds (photographs by Ed Kashi)

International Territory: The United Nations, 1945–95

(photographs by Adam Bartos)

Vanity Fair’s Hollywood (with Graydon Carter and David Friend)

Left Hooks, Right Crosses: A Decade of Political Writing

(edited with Christopher Caldwell)

Is Christianity Good for the World? (with Douglas Wilson)

Hitchens vs. Blair: The Munk Debate on Religion (edited by Rudyard Griffiths)

First published in 1995 by Verso, an imprint of New Left Books.

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Christopher Hitchens, 1995

Foreword to the Atlantic Books edition copyright © 2012 by Thomas Mallon The moral right of Christopher Hitchens to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Thomas Mallon to be identified as the author of the foreword has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 224 2

E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 840 1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Edwin and Gertrude Blue: saintly but secular.

Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgments

Introduction

A Miracle

Good Works and Heroic Virtues

Ubiquity

Afterword

Foreword

During the middle of the last decade, in his great period of political apostasy, Christopher Hitchens often entertained, along with his older left-leaning pals, a sprinkling of younger conservative journalists and operatives, all of them not only thrilled to be in his company—who ever wasn’t?—but also grateful and deeply reassured to have such a blue-chip intellectual on their side of the Iraq War, that historical moment’s great divide.

I would smile quietly while these young men cheered him on and hear-hear’d. Just wait, I’d think, knowing the moment would arrive when the ideological fiddler would have to be paid, when the host would change the topic and the earnest and happy young men would be reduced to looking at their shoes and muttering Oh, well, yes, I suppose. I like to think of this as the Mother Teresa Moment, named for Hitch’s most incendiary cultural dissent but applicable to any subject that might startle the Christian soldiers of the Bush administration into remembering that, apart from Saddam Hussein, Hitch remained entirely his unreconstructed secular and socialist self.

Hitchens’s disdain for the “thieving, fanatical Albanian dwarf”—i.e., Mother Teresa—became so famous that new readers of The Missionary Position may be surprised to discover that the phrase appears nowhere in this slender volume. If the book’s main title produces a guffaw, its subhead (“Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice”) more closely tracks its spirit. Far from being some cackle of defilement, or even just a bit of bad-boy blasphemy, The Missionary Position is, in fact, a modest, rational inquiry, a calm lifting of the veil that drapes its sacred subject. “Once the decision is taken to do without awe and reverence, if only for a moment,” writes Hitchens, “the Mother Teresa phenomenon assumes the proportions of the ordinary and even the political.” The author wishes to examine his subject’s public pronouncements, her finances, projects and associates, and to judge “Mother Teresa’s reputation by her actions and words rather than her actions and words by her reputation.”

Does anyone have a problem with that?

What’s under the veil turns out to be pretty unsightly: Mother Teresa’s missions—backed by a yachtful of grifters from Haitian first lady Michèle Duvalier to 1980s S&L fleecer Charles Keating—are revealed to be less concerned with eliminating the poverty of the poor (and even their attendant physical pain) than with extending those things as their means toward salvation in the afterlife: “The point is not the honest relief of suffering but the promulgation of a cult based on death and suffering and subjection.” Hitchens’s most devastating source is “Mother” herself: She “has never pretended that her work is anything but a fundamentalist religious campaign,” through which the poorest of the poor, the least of these, must grin and bear it until they’re transmuted from being the last to the first.

Hitch being Hitch, he cannot, here and there, resist pouring it on for the reader’s edified delight. Commenting upon the decision of advice columnist Ann Landers to share one of Mother’s prescriptions for improving the world (“smile more”), he writes: “It is . . . doubtful whether a fortune-cookie maxim of such cretinous condescension would have been chosen even by Ann Landers unless it bore the imprimatur of Mother Teresa, one of the few untouchables in the mental universe of the mediocre and the credulous.”

But The Missionary Position remains less a polemic than an investigation rooted in personal passion. In the manner of such intrepid, also-departed colleagues as Oriana Fallaci and Ryszard Kapuściński, Hitchens traveled the world toward eruptions of what fundamentally agitated him, and that was tyranny. “This is,” he writes in the book’s original foreword, “a small episode in an unending argument between those who know they are right and therefore claim the mandate of heaven, and those who suspect that the human race has nothing but the poor candle of reason by which to light its way.” Preferring “antitheist” to “atheist,” Hitchens liked to draw comparisons between Christianity and North Korea, both mental kingdoms offering their inhabitants the chance to commit “thought crime” and to deliver “everlasting praise” of the leader.

This small book is part of a big career devoted to pulverizing cant, deflating oppression, and maximizing human liberty. Not a day went by that Hitch didn’t enter the lists against some iniquity. Nearly all his causes were noble; a few were quixotic and probably not worth his time. I remember one piece he wrote a half-dozen years ago in defense of free speech for David Irving, the Holocaust-denying historian. Writing against the clock, with his usual urgency, he made a slip of the keyboard in an attempted reference to one of Irving’s editors, putting down “Thomas Mallon” for “Thomas Dunne.” Oh, joy, I thought, seeing my name mistakenly next to Irving’s in the pages of The Wall Street Journal. I sent Hitch an e-mail that began, more or less: “I know that to the sons of British naval officers all of us Micks must seem the same, but . . . .” He responded late that night with “Oh, fuck,” or words to that effect—no apology, just an injunction to turn up, the next day, at a demonstration he was organizing to support the Danish cartoonists who’d recently had the temerity to draw the prophet Mohammed. I thought about going, knew that I should, and finally never made it. If you want one more epitaph to add to all the ones that already have been suggested for this dual man-of-letters/man-of-action, let it be: He Showed Up. Throughout his life and times, whenever and wherever something important was on the line, he presented himself.

The Missionary Position appeared in 1995, eight years before Mother Teresa’s beatification, an occurrence that Hitchens had seen rushing our way. He notes in his text how Pope John Paul II was readying so many candidates so quickly for this enhanced status (“the ante-room to sainthood”) that the process had begun to “[recall] the baptism by firehose with which Chinese generals Christianized their armies.”

In the event, Hitchens played a necessary, if negative, role in Mother Teresa’s elevation, testifying before an official church body as to her unworthiness. He explained the task, undertaken in 2001, in the magazine Free Inquiry: “The present pope . . . has abolished the traditional office of ‘Devil’s Advocate,’ so I drew the job of representing the Evil One, as it were, pro bono. Fine by me—I don’t believe in Satan either.” The writer’s wife, Carol, can recall sending Hitch off to Father David O’Connor of the Washington, D.C., archdiocese to perform this strange and futile exercise in debunking, and then welcoming him home to lunch in their apartment on Columbia Road, as if he’d just come back from a radio interview.

Another, even more significant, development—this one, too, coming years after The Missionary Position—was the publication of Mother Teresa’s letters. The spiritual doubts they were discovered to contain created a sensation worthy of the cover of Time. Let me present just one extract: “Jesus has a very special love for you,” Mother Teresa wrote to the Reverend Michael Van Der Peet in 1979, the year she received her Nobel Peace Prize. “As for me, the silence and the emptiness is so great that I look and do not see, listen and do not hear.” No, let’s quote one more passage, just in case this was some momentary slip: “I am told God loves me—and yet the reality of darkness & coldness & emptiness is so great that nothing touches my soul.”

You mean you’re not sure?

Had these letters been available to him in the 1990s, I can hear Hitchens asking Mother Teresa just that question, face-to-face, as she showed him around the Calcutta orphanage. And it seems to me that the existence of such doubts makes her enterprise all the more breathtakingly presumptuous: She in fact was not one of “those who know they are right.” She felt no certainty that the poverty she was barely palliating would lead its sufferers toward an eternal reward. It is one thing to take Pascal’s wager and bet on the existence of God, no matter what one’s doubts may be. But to lead thousands of others to the gaming table, insisting that they double down with their one paltry handful of chips?

After his cancer diagnosis, I often prayed, on my knees and through all my own doubts, for Hitch. Not for his soul; just for his earthly continuation. Nothing bothered me more during the long months of his illness (and suffering) than having to watch interviewers ask him if he might now not be ready to change his mind on matters cosmic. He met such inquiries with a sort of Christian forbearance, treated them as one more teachable moment in which he could explain his position. And throughout this grim period, by his conduct and example, he provided me with one specific religious certainty, the only one I’ve had in a very long time: If God does exist, He would have been deeply disappointed in any renunciation of nonbelief by Christopher Hitchens, that spectacular piece of His handicraft, the worthiest foe among all His brilliant, wayward sons of the morning.

Thomas Mallon

February 2012

One may safely affirm that all popular theology has a kind of appetite for absurdity and contradiction. . . . While their gloomy apprehensions make them ascribe to Him measures of conduct which in human creatures would be blamed, they must still affect to praise and admire that conduct in the object of their devotional addresses. Thus it may safely be affirmed that popular religions are really, in the conception of their more vulgar votaries, a species of daemonism.

David Hume, The Natural History of Religion

Nothing to fear in God. Nothing to feel in death. Good can be attained. Evil can be endured.

Diogenes of Oenoanda