Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

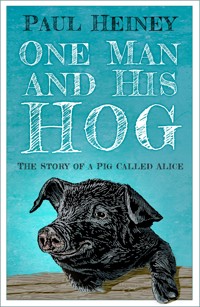

'To call Alice "just another pig" would be the gravest insult.' Alice the Large Black pig was Paul Heiney's best friend, his confidante and his therapist. This is the story of their tempestuous relationship with all its ups-and-downs, from her arrival as a 'large, black and expensive' Christmas present for his wife to her last days as the matriarch of his traditional farm. In One Man and His Hog, Heiney walks us through why lop-eared pigs are the best to raise (they can't see you coming), how to escape a sow that's decided you're her next mate (throw a bucket and run), and how, actually, pigs might have just got this whole 'life' situation sorted out.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 161

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2019

This paperback edition first published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Paul Heiney, 2019, 2025

Illustrations © Martin Latham, 2019, 2025

The right of Paul Heiney to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 356 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

Contents

Who Was Alice?

A Quick History of Pigs

My First-Ever Pig

Thirteen Pigs for the Price of One

A Pig – the Perfect Present?

Sleeping Next to a Pig

Persuading Pigs

A Nose for Food

Keeping Pigs – a Moving Experience

Alice – a Catastrophic Pig

A Palace for Alice

Alice Has Her Cake and Eats It

Huffing and Puffing

Alice Needs a Mate

True Love – Not Running Smoothly

Pig Sick

Why a Pig Will Never Get Lost

Who Could Take Her Place?

Let’s Give Polly a Ring

What is it about Pigs?

Thank You, Alice

1

Who Was Alice?

To call Alice ‘just another pig’ would be the gravest insult. She was far removed from the ordinary, the common-or-garden, the routine. She had qualities that elevated her above the commonplace members of that species. All pigs are special, as those who have kept them will tell you, but there was something about Alice that went way beyond. She had a profound effect on me. If anyone were to ask, ‘who has influenced you most in your life?’ my first thought would be Alice.

She was my friend for the best part of a decade. We talked to each other on a regular basis and she listened patiently. I tended and cared for her and in return she gave me comfort too. There is a deep kind of pleasure to be had in the company of a pig (especially Alice) and even more if, in a shared moment, you lean over the wall of her sty and stroke her back with a stick, because pigs like that. Alice would have rolled her eyes, if she could. Blissful hours can be spent just watching a pig, and before long you will find yourself in the same kind of meditative state of mind that mystics seek. There is much medicine prescribed to treat a weary mind, but if doctors would recommend an hour a day talking to a pig, what a boost that would be to our spiritual health.

Much praise has been heaped on the pig for the multiplicity of its gifts. We know from countless writers that a human in need of food can use every part of the pig ‘bar the squeak’. From their skin to their hearts, there is always something to be found that, with a little cooking skill, will make a fine feast. This much is well known.

But during those quiet moments that Alice and I shared, I often wondered if this pig had more to offer than just her flesh. Having watched how pigs behave – and in particular how Alice led her life and reared her offspring – I came to believe that, here before us, in every field and every sty where pigs are kept, there are lessons that we might learn to help us lead an improved life. Is it possible that pigs have a philosophy? Could it be that they have got life worked out to such an extent that their contentment is complete, and their troubles are few? I believe it to be so, and in the years during which I knew Alice I tried to unravel what this secret might be.

She was the only pig with whom I could hold a genuine conversation. It took time, of course, but soon I learned how to ask if she was happy with her sty, comfortable in her straw or generally at peace with the world. And if it was me who was going through a stressful patch – a common state of mental affairs for farmers large and small – then it was she who could calm me. In fact, she had almost medicinal potential as a soother of the fevered brow.

Alice inspired me in many ways. She forced me to think more deeply than ever before about the working relationship between a farmer and his animals, and what it tells us about ourselves. She also served to bring into sharp focus the damage that has been done to our respect for farm animals in the relentless pursuit of food that must be profitable, whatever the cost to an animal’s dignity. Some people will look at a pig and see only chops, where I observed deep truths.

When we talk about Alice, we are speaking of a figure who was a true giant amongst her generation. She captured the hearts and imaginations of thousands who had never even met her through my writings in The Times newspaper over twenty years ago, where she was often mentioned, and my recollections here are drawn from my diaries at the time.

As pigs go, Alice the Large Black pig was as influential a sow as ever lived and when she died, she was mourned the length of the country. She was the people’s pig. If ever a pig had greatness thrust upon it, it was Alice. Humbly born and expecting no more from life than the drudgery of rearing of piglets, Alice accidentally found fame. Call it charisma, call it star quality, Alice had it from the tip of her slimy snout to the very end of her curly tail. Once, from the far side of a crowded Oxford Street in London came the cry, ‘How’s Alice?’ She was known everywhere. A rock star would have been jealous of Alice’s mailbag, yet she took it like the lady she was and was patient and gracious with all enquiries. What a shame she didn’t live to see the growth of YouTube, for she would certainly have been an influencer to be reckoned with, and certainly more intelligent than some. Now and again she showed a certain impatience with time-wasters: no disgruntled duchess ever gave a look more thunderous than that given by Alice, the Large Black pig. But, on the whole, I was lucky. With all that public attention she could have turned into a monster, but she remained to the very end the sweetest pig in the world.

By the way, don’t imagine this is going to be one long, drippy lovelorn tale. If you think all this love and affection that I have been hinting at so far is going to be maintained, think again. She could be stubborn, abusive, violent and a complete bitch, all within the space of five minutes. No petulant rock star could outdo Alice when it came to temper. This relationship, believe me, was up and down like a yo-yo. But that, of course, is all part of the mystery of a pig called Alice.

2

A Quick History of Pigs

You had only to look at Alice to realise that whoever invented the pig did a damned good job. There are estimated to be 800 million of them now, honking and squealing in every corner of the world, although the loudest din will come from China, which has over half the world’s pig population. That’s a lot of piggies. And they produce a mighty mountain of meat – 60 million tons of pork a year in China alone, making it the world’s most widely consumed meat.

It is a remarkable success story for a creature with a miserable beginning. The wild boar, from which our much friendlier Alice is descended, was not the sort of creature to meet on a dark night, nor one to find yourself within snapping distance of. You couldn’t possibly be fond of a wild boar. It’s a surly, bristled creature with mean eyes and a threatening snout, and the sharpest of teeth that could rip you apart with ease. Nevertheless, the police in Logroño, Spain, have one as their mascot and take it around on a lead, like a dog. It is far from clear whether it is the armed officer or the long-haired boar with a body the size of a muscular pony that is more likely to deter crime. It would be those evil tusks that would do you most damage, assuming you hung round for long enough, which you wouldn’t because the boar has an ability to threateningly raise its fur along the length of its spine till it looks like a dragon from a children’s book. One glimpse of that and your courage would surely evaporate. In fact, where wild boar hunts are written of in Scandinavian texts and Anglo-Saxon writings, they are described as being for only the truly courageous. Remember also that in the list of the Labours of Hercules, catching the Erymanthian Boar comes fourth. Assuming his tasks were in ascending order of difficulty, he would have already tackled a monster lion, a serpent and a hind with golden antlers before getting round to this wildest of pigs. Incidentally, his next task was to clean the Augean stables, which might be thought of as a bit of a doss after all that wild animal grappling. In fact, the stables, which housed a thousand cattle, had never been cleaned in thirty years. The inventive Hercules re-routed the flow of two rivers to eventually wash them out and thus avoid himself a truly Herculean effort with a muck fork.

But how do we get from the feared wild boar to the tractable, kindly creature we know and love – the farmyard pig? What happened to that vast family, of which Alice was a part, that reformed the wayward boar into the domesticated pig? When did those nasty pieces of sharp-toothed work transform themselves into cuddly Miss Piggy? How did fear and loathing of a species end up with the very same being beloved by generations of children, most recently through Pigling Bland, The Sheep-Pig, and, of course, Wilbur from Charlotte’s Web?

It all started badly. For example, take what was known as the ‘Irish Greyhound Pig’, which was very similar to the earliest of pigs. They had long legs and great strength at their back end and were said to be able to jump over a pony if not a five-barred gate. They were, however, bony and not covered with much meat, carried coarse hair and had pendulous wattles hanging from their throats. It was a direct descendant of the pigs that had roamed the forests of Ireland since prehistoric times. Although now extinct, an Englishman, Sir Francis Head, came across similar animals in Germany and wrote:

As I followed them this morning, they really appeared to have no hams at all; their bodies were as flat as if they had been squeezed in a vice; and when they turned sideways their long sharp noses and tucked-up bellies gave to their profile the appearance of starved Greyhounds.

The Rural Cyclopaedia, written by Revd John M. Wilson in 1848, pulled no punches and the author showed little Christian compassion to this clearly indifferent animal:

It is ugly, bony, razor-backed, lank, coarse, greedy, a voracious eater, a most unkindly feeder, and exceedingly difficult to fatten; and even in its best state, it yields pork and bacon far inferior to those of almost all the improved breeds. Its best recommendation is that it has disappeared from all comparatively enlightened parts of Ireland and is rapidly disappearing from even the remote and most neglected districts. Yet, with unutterable absurdity, it is still preferred to every other hog by a few of those halfmad antiquity-loving peasants who can see nothing but horror and ruin in any kind of deviation from the practices of their fathers.

The long, slow transformation of the pig started around the time of the early Bronze Age (2000 BC) when domestication kicked off with the intention of dissuading the ever-greedy pig from destroying every crop it could find. Having lived in an unconfined way since their creation and able to wander and do damage where and when they could, teaching them to live confined lives was an optimistic task for an ancient stock-keeper.

But it worked. Fifteen hundred years later, pigs were kept and gorged on by the Romans, who made pork their principal form of meat. But the pig as a successful commercial animal, rather than just a casual source of food, is a much more recent development. Robert Bakewell, born 1725 and described by the Breeder’s Gazette as ‘the patriarch of animal breeders’, had made a major contribution to the development of cattle and sheep by breeding in a methodical way, although his influence on the pig was insignificant except upon a breed known as the Small White. Bakewell preferred to work in secret, so exactly what he did with the Small White we shall never know, except to say that as a breed it is now extinct. Some of his breeding resulted in pigs that were described at the time as ‘rickety’ or ‘fools’. However, his work with Leicester sheep and Longhorn cattle led to a wider understanding of how desirable traits in animals could be preserved and enhanced through selective breeding, which was a major breakthrough in animal husbandry. But perhaps his success with pigs suggests that they might have been cleverer than him. I have always detected a certain arrogance in pigs and it is quite possible that Bakewell’s piggy subjects simply thought that they could not be improved upon and so ignored his experiments. By behaving like ‘fools’, they may have been making a fool of him.

The problem with the Small White, and all other pig breeds around that time, was that their keepers were not farmers but aristocratic hobbyists whose main interest was taking them to shows, winning cups, and being proud of them. They wanted to be seen owning pigs that were eye-catching: fatness was all that mattered. A glance at the engravings of the time shows pigs of the most hideous conformation, and a modern health adviser would surely be gasping as they struggled to speak the words ‘morbidly obese’. And they were – fat as pigs. The result was that they hardly appealed to any palate, no matter how much the poor consumer might have enjoyed a bit of fat on their meat. In fact, it was more a case of a bit of meat on their fat.

To make it even more difficult for them to hold on to a slender frame, pigs became a convenient method of waste recycling. They were the first consumers of junk food. The big London breweries at the end of the eighteenth century fattened no less than nine thousand pigs a year on brewers’ grains and all the other waste that came from the rapidly expanding brewing business. They were useful too to the dairy farmer who had to dispose of whey, the by-product of cheese making. Boy, did pigs grow fat on that as well.

Fatness trumped everything when it came to pigs. The lashings of lard that surrounded pig meat were colossal by any measure, and the old wild boar suddenly found that it had been transformed over a couple of thousand years into a ridiculed creature, and not a productive or nutritious part of the army of animals that farmers reared to make themselves a living and provide us with food. It is probably from this time that the use of the word pig as an insult took hold. Anyone who was lazy, filthy or greedy was now called a ‘pig’. Gluttons were said to ‘eat like pigs’ or ‘have the table manners of a pig’. These days, in urban jungles, wayward youths will call the police ‘the pigs’, meaning they are seen as the lowest form of life. Middle-aged pink-faced men of conservative views are now being called ‘gammons’; the creators of this insult presumably being unaware that the gammon is one of the pig’s sweetest and richest gifts and to be revered. But it all goes back to those selfish, hobbyist aristocrats, probably fat themselves, who believed that, when it came to pig, big was beautiful and that was all that mattered. So horrified was the Revd Henry Cole that he wrote to the Royal Agricultural Society in 1852 having observed the pigs at a show in Brighton:

My pain arose from witnessing animals unable to stand, and scarcely able to move or breathe, from the state of overwhelming and torturing obesity, to which they had been unnaturally forced. Nor could one of the unhappy prized pigs, or of those exhibited to contest the prize, stand for one moment. And, if punished by being partially raised to gratify the brutish curiosity of a few, they laid themselves down, or rather fell down immediately. And it appears, that several died in their cart-conveyance to the scene of this cruel and unchristian exhibition.

In the nineteenth century, breeders began to realise that by judicious mating of breeding stock drawn from a wide range of differing breeds of pig, a more acceptable and leaner kind of meat could be produced. All of a sudden, the pig found itself in the ascendency. Gone were the old beliefs, best expressed by William Cobbett in his Cottage Economy when he wrote of the pig:

If he can walk two or three hundred yards at a time he is not well fatted. Lean bacon is the most wasteful thing that a family can use. In short, it is uneatable except by drunkards who want something to stimulate their sickly appetites.

I wonder what view Cobbett would take of a modern supermarket display of bacon, bred for minimal fat, a sliver of it twixt meat and skin, so slender that a magnifying glass might be needed to spot it? Cobbett was right, though, but only up to a point; bacon or pork with no fat is a tedious and flavourless kind of meat to eat. But there are limits, and perhaps a pig that is so fat that it can’t get from one side of field to another without a lie down to get its breath back, might not produce the healthiest of foods.

And what has any of this to do with a pig like Alice, except that, clearly, she was a pig herself? She was of a breed called the Large Black, doubtless a creation of the genetic meddlers like Bakewell and those who came after him. And yes, she had a certain stoutness about her, I can’t deny it, although I would never have dared to mention it in front of her –