Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

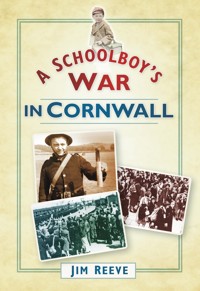

Although only children at the time, the Second World War had a permanent effect on the schoolboys who lived through the conflict. Watching a country preparing for war and then being immersed in the horrors of the Blitz brought encounters and events that some will never forget. Now in their seventies and eighties, many are revisiting their memories of this period of upheaval and strife for the first time. In this poignant book, the author shares vivid memories of his evacuation from war-torn London to the comparative safety of places like Newquay, St Ives and Redruth in Cornwall. From touching recollections of enjoyable days spent with loved ones to the dark moments of falling bombs, this is an honest account of a wartime child's formative years. Together with rare images and accounts from fellow evacuees who were sent to Cornwall to escape the ravages of war, this book reveals how these experiences are indelibly inscribed on the minds of wartime children.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 243

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A SCHOOLBOY’S

WAR IN CORNWALL

A SCHOOLBOY’S

WARIN CORNWALL

JIM REEVE

First published 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Jim Reeve, 2010, 2010, 2013

The right of Jim Reeve to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5275 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1

War is Declared

2

The Journey

3

We Settle In

4

Parents’ Visits

5

Schooling

6

Rumours Abound

7

Enemy Action

8

Mistreatment

9

Entertainment

10

Returning Home

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the many people who have assisted me in compiling this book and who have generously given me their time, shared their evacuation experiences and loaned me their precious photographs. I would especially like to thank Jim Wright of the Evacuees Reunion Association, who has been so helpful in supplying photographs and information; the editor of the West Briton, Richard Vanhinsbergh, for printing my letter in the paper, to which I had so many replies; the staff of the Redruth Library; the staff of the Truro Museum; Angela Broome, BA (Hons), at the Courtney Library Cornish History Research Centre; Steve Perry at his excellent Cornwall at War Museum in Davidstow, a museum not to be missed on any visit to Cornwall; Mr and Mrs May at the Great Western Hotel; Mr Cooley and Mr Stephen Smith at the Atlantic Hotel, who were so helpful; the voluntary staff at the Maritime Museum, Falmouth, and, in the order I interviewed them, Mrs F. Bishop; John Glyn; Eileen Penwarden; Roger and Wendy Watson; Madeline Fereday; Professor Ken MacKinnon; Edna Goreing; Dave Thomson; Mrs Sheila Nicholls; Mrs Jones; Ken Foxon; Yvonne Watson; Stan Mason; Sheila Sells; Harry Drury; Mrs Murt; Mary Garnham; Brian Little; Mrs J. Harris; Mr Clark; Mr R.A. Cook; Mrs Jean Pickering (née Desforges), who represented Great Britain in the 1952 Olympic Games; Mr Wills; Nancy Botterell; Ian Blackwell; Clive Mathison; Anne Vaughan; Elsie and Rose Bristol, Mrs Pellew (née Gribble); Mrs M. Pascoe; the three Horton sisters, Betty, Irene, and Olive; Peter Butt; John Reid; Mr Shire; Michael Duhig; Olive West; Mr and Mrs Trip; and Mrs Patricia Free (née Wood). Also, my gratitude goes to my editors, Sophie Bradshaw, Nicola Guy and David Lewis; my researcher and good friend Olive Norfolk; my wife, Joan, for her help, support, understanding and editing skills and, finally, to all the people who took us in during those turbulent times.

INTRODUCTION

It is important to record the wartime experiences of ordinary children who were evacuated before their memories are lost in the mists of time. This book sets out to log the experiences of children, often as young as four years old, who were evacuated from the danger zones that were targeted by the German Air Force. Many readers may disagree with some of the facts mentioned, but these are the memories of people as they recalled them, and one should bear in mind that the events took place over seventy years ago.

During the First World War, towns were bombed by the German Zeppelins and Gotha bombers and therefore it was realized that as we slipped reluctantly towards the Second World War, a scheme of evacuation had to be planned. As Stanley Baldwin MP said, ‘The bomber will always get through.’ As far back as 1931, a sub-committee was set up to examine the problem of evacuating the young and vulnerable away from the danger areas. The plans were well advanced by the time Chamberlain made his famous remark of ‘peace for our time’ from the window of 10 Downing Street after returning from Munich and giving his famous speech on the steps of the Lockheed plane at Heston Airfield in September 1938.

The government took measures under the Emergency Powers Act in August 1939 which enabled them to commandeer houses, restrict menus to one item, close theatres and cinemas and force factories to manufacture whatever was needed for the war effort to ensure victory. From 1 September, and for the next few days, 3,000 buses were commandeered, routes along main roads were changed to one way only and 4,000 trains took the children to safe parts of the country. The evacuees were not told where they were going, which created an air of excitement and anticipation. There were 1,200 helpers but everyone at the stations became involved; policemen carried cases and porters helped mothers with young children as everyone had a single purpose in mind: to get the children safely away. Whole schools were evacuated with their teachers but parents were not allowed to see their children off and stood outside the playgrounds in tears. The streets were alive with 1½ million children from every bomb-threatened area in the country. All of them carried a gas mask and food for the day. Their names were attached to their lapels. The declaration of the Second World War was two days away, but the invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 triggered ‘Operation Pied Piper’ and the great evacuation began. I remember it well!

When the children finally arrived at their place of safety, exhausted after their journey, they were lined up in village halls, schools and even sometimes on the station platform, where the foster parents picked out the ones they wanted. This often meant splitting up brothers and sisters. The badly dressed children from the poorer districts of the cities were often left till last. One woman, who is in her late seventies, commented, ‘It was like a slave market as I stood there waiting to be selected.’ The foster parents were paid 10s 6d per week for the first child and 8s 6d for further children. Householders who provided lodgings for mothers with children under school age were paid 5s per week, but the mothers had to provide their own food, etc.

Most children were treated well and many formed friendships which have lasted to this day, but to others the evacuation was a nightmare. Mrs Willingham from Bethnal Green, who was evacuated to Cornwall, had an appalling time and finished up being thrown down the stairs. She was bathed in cold water, even in the depths of winter. Some local children resented the evacuees and fights broke out. Evacuees often came from different backgrounds to those who fostered them; children from the slums were billeted with middle-class families who had no concept of what hardship was. Some children were so poor that they arrived without a change of clothes and their foster parents had to go out and buy new ones.

Inevitably, with vast numbers of people on the move, there were many mistakes. In some villages too many children arrived, giving billeting officers a headache in finding them places, while in others, the opposite happened. In fact, it was reported that some villages on the Yorkshire Moors turned out to welcome the evacuees in force but many of the villagers returned home disappointed because there were not enough children to go round. It is amazing that of all the children that were evacuated there was only one fatality; Michael Moscow, who came from London and was billeted in Market Harborough, was shot dead by his brother while they were playing with a shotgun.

The Minister of Health, Mr Walter Elliot, described the evacuation as the equivalent to moving ten armies. It was not compulsory and many parents were unwilling to part with their children. Of those that did go, 90,000 returned home within a short while because the expected bombing did not happen, but when the Blitz did start in earnest in 1940 there was another great exodus from the cities.

My mother was determined that Hitler was not going to drive her out of her home but quickly changed her mind when a bomb wrecked our house in 1940. Because my brother was a baby, my mother accompanied us and we finished up in the very classy Great Western Hotel in Newquay, Cornwall, which for me was a great adventure. Many children went to Canada, America and Australia but, sadly, the SS City of Benares, which was bound for Canada with ninety children on board, was torpedoed by the German U-boat U-48 and sank. Only thirteen children were saved by HMS Anthony, 500 miles off the north-west coast of Ireland, on 17 September 1940.

To celebrate the seventieth anniversary of the start of the evacuation, the Evacuees Reunion Association held a service in St Paul’s Cathedral on 1 September 2009, where approximately 2,000 evacuees gave their thanks for having come through the journey into the unknown.

Jim ReeveSeptember 2010

1

WAR IS DECLARED

The day before Hitler invaded Poland, the final of three warnings went out to ‘Evacuate Forthwith’. Mothers and families who lived in a region designated as an evacuation area, and who had volunteered to send their children to a reception area, began to say their goodbyes. For a while, children had gone to school with their gas masks, enough food for the day and carrying clothing, according to instructions that had been sent out by the schools on orders of the government, who did not know when the order to ‘Evacuate Forthwith’ would come. The only person in the schools who knew the destination of the children was the headmaster and he was sworn to secrecy. Parents did not know where their sons or daughters were until they received a postcard from their child once they had arrived at their destination.

At first it was decided that children should go with their schools, but given one child from a family could go to a senior school and another to a junior school, it was soon realized that they would be split up. There was such an uproar that the government soon changed its mind and children from the same family went together, although many were often separated when they reached their destinations.

Children were not the only ones evacuated. Mothers with children under school age, pregnant women and invalids also left and a number of hospitals were emptied out. Many evacuees were lucky enough to be sent to Cornwall and set out in this chapter are some of their experiences of how their parents came to make the decision to send them away to safety.

The first evacuation, which started on the 1 September 1939, was well organised considering the number of people involved but, to a certain extent, was a waste of time and money because the expected bombing of the cities did not take place. There was some bombing of ports and shipping but not towns. In view of this, parents began to believe that the government had exaggerated the risk and had got it wrong and it is estimated that 90,000 children returned home.

My mother had made up her mind that the war was not going to force her to leave home and so she decided not to have me or my brother Billy evacuated when the war started on 3 September 1939, until her mind was changed one night a year later after the Blitz had started in earnest. We lay on a mattress on the basement floor, under an old, wooden kitchen table, listening to the symphony of death as bombs cascaded out of the night sky onto London. Mum spread herself across us like a broody hen, gathering us beneath her great frame. Terrified, my Aunt Milly curled up beside us uttering, ‘Oh my God, that was close. Lou, you must get the kids inoculated.’

‘You mean evacuated, don’t you?’ Milly always got things wrong and Mum was always correcting her. Another bomb exploded and I remember snuggling closer to Mum. Suddenly our whole world seemed to implode and chunks of glass flew across the room. Lumps of plaster crashed to the ground, sending up clouds of dust. To add to the chaos, Billy started screaming.

Mothers were urged to evacuate their children.

In July 1940, as we lay there under the table with Billy yelling in my ear, I was terrified and then, suddenly, a loud noise penetrated the air in one long, continuous note, a sound we would welcome each time we heard it, for it would mean we had survived another enemy raid. Very carefully, we crawled out of our sanctuary, trying to avoid the glass which was scattered across the floor. Mum carried Billy in her arms while Aunt Milly took my hand and led me up the stairs. I remember looking up and, to my surprise, seeing the sky and wondering why? Then I realized the front door was hanging off at an angle and clinging to the frame by one hinge. Just as we reached the top of the stairs I saw a helmet poke over the limp door with ARW (air raid warden) painted in white on it. In a cheerful voice he shouted, ‘You alright down there?’ and with one accord we shouted back ‘Yes!’

The air was filled with dust as we stepped over the rubble and glass and carefully climbed the stairs. Our house had three bedrooms. Mum and Dad had one, Billy and I had another and the third was used as a storage room. Mum stepped into ours and screamed. Looking round Mum, I saw daylight where our window had been. ‘Look, look at Jimmy’s bed. Thank God he wasn’t in it!’

My heart missed a beat as I saw a great window lintel lying across my bed. Had I been in it, I would have been killed. Mum was still carrying Billy on one arm but with the other she encircled me and pulled me to her. With her great arm around me all the fear of the previous night vanished. She always had that power to make me feel safe. The other rooms had not suffered as much, although the windows were out; it might have been that our room was at the front of the house. We discovered later that a bomb had fallen a little way up the road. When we went into the kitchen, we were surprised to find it had hardly been touched. Mum sat down and said, ‘Let’s have a cup of tea, I think it’s safe. I can’t smell gas.’ So we sat in the kitchen drinking strong, hot, sweet tea, which seemed to be the cure for all the ills of the world in those far-off days.

We all started to clear up the mess except Billy, who was left in the playpen in the kitchen with his favourite teddy bear. I was warned to mind the glass but I suspect I was more of a hindrance than anything else. That afternoon some men came round and boarded up the windows and made some temporary repairs to the damage in our room and declared that the house was safe. They promised they would be back when they had some glass. To my knowledge, we never saw them again as I can remember how dark it was until we were evacuated.

While I drank my tea I thought back to how it had all begun. I did not understand this talk of war. The adults seemed to talk of nothing else, but up to then there had been no bombing or anything to give me a clue as to what it was all about. Our only sources of news were the radio, or wireless as we called it, the newspaper or the cinema. The television was in its infancy and only had 25,000 viewers; we were not one of them. Actually, television was first broadcast from Alexandra Palace in August 1936. Its range was limited and only London and the eastern counties could receive it. We beat the Americans to television by five years and it was not until 1941 that they first broadcast. Screens were black and white of course. Everything went out live, there were no retakes like today, and if there were any mistakes they were there for all to see. The television showed such things as plays and sports, for example, the Boat Race, boxing matches and the FA Cup. Then at midday on 1 September 1939, they stopped broadcasting until 1946. Apparently it was believed that the short wave frequencies could guide enemy aircraft to their targets. The other factor was that many of their technicians joined up or transferred to radio, which was thought to be the better service. We are lucky today with twenty-four hours of coverage; in those days it was restricted. In our house we did not even have electricity; our lighting was by gas with mantles, which, if touched after being used, would shatter into hundreds of pieces. Of course, as a child I was curious and could not help climbing up and seeing them disintegrate.

In view of the fact that we had no electricity, our radio was run by an accumulator which we had to get charged at our local garage. The batteries were so heavy that Mum had to run them down to the garage on the pram. The process took a couple of days so Dad bought a spare battery so we had one charged all the time. There were 8½million radio licences across the nation and although the sets looked primitive, being run on glass valves inside square boxes or the cat’s whisker, and the sound sometimes faded, they were our main source of entertainment.

All this talk of war puzzled me and so one day I asked, ‘Mum, what is war?’ She looked at me, not quite knowing how to answer the question, and after a few moments replied, ‘It’s like you and your brother. When he wants something and you will not give it to him, what do you do? Fight! Countries are like that. Old Hitler wants more power and space and so he’s fighting us for it.’ I still did not quite understand.

Before war was declared in 1939, there was a sense of fear and trepidation in the adults. We children were excited and played soldiers with sticks as guns. Little did I know that some of our soldiers were so short of rifles that they were drilling with broomsticks! My father had joined the Territorials long before there was any talk of war and soon I noticed that he started going out for training more and more. He was out most nights and when he was made up to a sergeant, I remember Mum sitting in front of the fire in the front room sewing on his stripes. During the day he worked as a porter at Euston station and in later years he became a union leader. Although we were proud of him, he was like most fathers in those days – very strict! If I cheeked Mum or could not tie my shoelaces, he would pull my trousers down and bend me across his knee and whack me with his slipper until I bawled my eyes out. In those days it was an accepted way of keeping discipline and the saying was ‘children should be seen but not heard’.

In September 1939, somehow everybody knew that Chamberlain was going to make a statement on the radio; it was on everyone’s lips and grown-ups talked of nothing else. He had been to Munich in the previous September and came back waving a piece of paper on the steps of a plane. He declared ‘peace for our time’ but had surrendered part of Czechoslovakia. Hitler was not satisfied with this and stormed into Poland on 1 September 1939.

There was a sense of excitement and fear as we sat round the radio in the front room, Dad and me on one side and Billy sitting on Mum’s lap on the other, each leaning forward to catch every word. I knew by the worried look on Mum’s face that it was important. Suddenly, in solemn tones, the announcer said, ‘the Prime Minister.’ After that, I only remember the words ‘and therefore we are at war with Germany’ because the radio faded. For a moment, we just sat there, stunned. Within moments there was a loud wailing and Dad shouted, ‘That’s the air-raid warning. Get downstairs, in the basement. We’ll get under that old table.’ We rushed downstairs, Billy bouncing around in Mum’s arms, while Dad urged me on. There was not enough room for Dad under the table and so he lay beside us, on an old sheet on the floor with his hands over his head. I don’t know how long we stayed there but, to a young, energetic boy, it seemed a lifetime. I listened hard, expecting any moment for a bomb to come through our ceiling and kill us all.

After what seemed hours, a loud, continuous wail filled the air and not knowing what it was, I snuggled into Mum for safety. Dad laughed as he rose from the floor and shook his head, ‘That must have been a practice run. I’m going outside for a smoke.’ Everybody smoked in those days; normally if you were working class it was Woodbines. Suddenly, he came rushing in calling, ‘Lou, Lou, [that was Mum’s name] come and look at this!’ We all trooped out into the back garden and at first I did not see what he was going on about until he pointed to the sky. I looked up and there were these giant silver balloons swaying about on long ropes.

‘What are they, Dad?’ I asked. Taking a puff on his cigarette he looked down at me, for he was over 6ft tall, and said, ‘They’re part of the air defence. It’ll stop planes flying low and machine gunning us because if they touch one, they will go up in flames.’ I was fascinated but could not see how they were going to deter the might of the German Air Force.

Soon after that day, Dad started packing up his kitbag and he and Mum seemed to cling to one another. Mum had tears in her eyes as she watched Dad moving around the house gathering up his things. He had been called up. The government conscripted men between eighteen and forty-one. In 1941, the age was put up to fifty-one but it was never really implemented and as far as it is known, no men over forty-five were called up. As Dad was in the Territorials, he was one of the first to go. Later, I learned that the government had brought in other powers, such as being able to seize any property they wanted; in restaurants there was a choice of only one meal; kites were banned; road signs were removed to confuse any enemy spies, and the government gave any wife whose husband had joined up protection against eviction.

Dad never showed me any affection but I remember him standing at the door, kissing Mum goodbye, and then he put his arm round me, drawing me close so that the material of his uniform tickled my nose and I could smell the distinctive scent of khaki. He whispered, ‘You’re the man of the house now. Look after your mother for me and behave yourself.’ He kissed Mum again and we stood at the door and watched him till he turned the corner at the end of the street. We were on our own and I had this great responsibility of looking after Mum.

The day after our first air raid, after Aunt Milly had gone home, Mum put Billy in the pram, which bounced along, while I held on to the handle and ran alongside. I noticed changes in our road; there were gaps in the row of terraced houses and rubble lay everywhere. Some of the houses had no slates and their finger-like rafters reached for the sky. I had no idea where Mum was taking us but there was a sense of urgency in her stride. ‘Mum, where are we going?’ I blurted out as I ran along beside her, my legs hurting. ‘I’ve got to get you away,’ she replied, ‘it’s too dangerous.’

We turned the corner and there in front stood this tall, ornate building which I think was the Town Hall. Like most important buildings, it had sandbags piled up to the first floor. Some authorities protected their buildings in various other ways, often by constructing some sort of fence and filling boxes with earth.

She parked the pram just inside the door and asked the porter where she should go to get us evacuated. The man looked down at her and smiled, ‘You should have gone the first time, love. Mind you, a lot have come back. The room’s on the first floor’ and he pointed up the winding stairs. Mum carried Billy, while I trailed behind as we climbed the steep, black marble stairs. I was fascinated by the paintings of what must have been previous mayors and the wooden panels. Exhausted, I looked up at Mum waiting at the top of the stairs. ‘Come on, Jim,’ she encouraged.

We walked along the very long passage, our steps echoing on the marble floor. In the distance sat a lady at a desk. Mum spoke to her and she indicated for us to sit down. Mum spoke to me in a whisper, ‘Jimmy, pull your socks up.’ They were always hanging round my ankles and seemed to be a constant worry to Mum but not to me. Suddenly, I jumped as the sound of a buzzer went off. ‘You can go in now,’ the lady said and opened the door. As we went through the door I saw a man sitting at a desk in the distance. He seemed to be miles away and we walked towards him, trying not to make too much noise. As we got close I could not help noticing that he had a moustache. The only person I had seen with one was Hitler. The man indicated to Mum to take a chair and while they talked I looked round the room, fascinated by the size of it and the decorations, especially the ceiling. It had, what many years later I learned, was egg and dart. Suddenly, my mum nudged my shoulder, waking me from my daydreams. ‘The man spoke to you. Where do you want to go, the country or the seaside?’

You were never told where, that was kept secret. I had never left London before except on a coach trip to Southend, where we went out on a boat, and based on that, I made the right choice and blurted out, ‘The seaside.’ I spoke for both Billy and me; well, he could not speak, so somebody had to reply for him!

So it was decided that we were going to the seaside, if we lived long enough, for each night the German bombers returned, laying waste London. Mum decided that while we were waiting for a letter to come notifying us when we were going, we would not be safe under the table down in the basement, so each night she would pack some sandwiches, cold tea in a bottle, a few blankets and would walk to the Bethnal Green tube station, where she thought we would be safe. At first the London Underground authorities would not allow people to go down into the tube but public pressure soon changed their minds. Little did any one realize that on 3 March 1943, 173 people would lose their lives in Bethnal Green tube station, including forty-one children. Apparently as the crowds started to troop down the tube, a bus pulled up and people started streaming off just as the ack-ack started firing. Some people thought it was a bomb while others were frightened of the shrapnel raining down on them from the shells. They panicked and rushed forward, tumbling down the stairs onto the men, women and children in front of them who were crushed underfoot or against the walls. There was an account later of a child being lifted over the heads of the crowd and thereby being saved. The tube did accommodate vast numbers of London’s citizens and at Bethnal Green that night, there were over 1,000 people. The slaughter was never reported and from accounts I have read, the next morning all the bodies had been cleared away and those on the platforms only heard rumours of the tragedy. The only thing that remained was piles of shoes. It was felt that if it was reported it would be bad for morale. Luckily for us, we were far away in Cornwall when this happened.

Newquay harbour, far away from the bombing in London.