Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jentas Ehf

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Historical Romance

- Sprache: Englisch

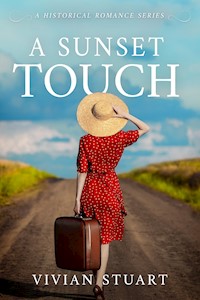

INTRIGUE. TENSION. LOVE AFFAIRS: In The Historical Romance series, a set of stand-alone novels, Vivian Stuart builds her compelling narratives around the dramatic lives of sea captains, nurses, surgeons, and members of the aristocracy. Stuart takes us back to the societies of the 20th century, drawing on her own experience of places across Australia, India, East Asia, and the Middle East. When Elizabeth Manners agreed to help take care of little Joey Randolph, she did so because she was sorry for the lonely, delicate little boy — but she certainly did not realise what a dangerous situation the child was in. It was a strange household in which she found herself. Joey's father, Jason Randolph, was pleasant enough on the surface. but Elizabeth soon realised that he was living under a great strain. And what about Kelly, his personal assistant and chauffeur, who wasn't like any chauffeur she had ever come across? Only when she found herself sharing Joey's danger did Elizabeth begin to appreciate Kelly's worth and to see him as something quite different from the arrogant. embittered man she had imagined him to be.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 369

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A Sunset Touch

A Sunset Touch

© Vivian Stuart, 1972

© eBook in English: Jentas ehf. 2022

ISBN: 978-9979-64-421-7

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchase.

All contracts and agreements regarding the work, editing, and layout are owned by Jentas ehf.

–––

For my daughter Vary—at her request and in the hope that she may consider it worthy of her.

Just when we’re safest, there’s a sunset touch,

A fancy from a flower-bell, someone’s death . . .

ROBERT BROWNING

CHAPTER ONE

‘There!’ Elizabeth Manners gave the injection with practised deftness. ‘You’ll feel better in a minute or two, Joey. Just lie still and try to relax the way I showed you, there’s a good boy.’

She smiled reassuringly down into her small patient’s thin, freckled face, watching for the adrenalin to perform its accustomed miracle. The boy’s struggle for breath became less agonising and gradually ceased altogether and, as the colour returned to his lips, he was able to purse them into an answering smile. But it had been a severe attack and Elizabeth wondered, studying him anxiously, what could have brought it on. During the past few weeks he had improved so much under the new treatment she had prescribed for him that she hadn’t expected this setback.

A neurotic element was, of course, always present in asthmatic patients and Joey Randolph was an unusually sensitive child. He was also very intelligent and, like so many American children, somewhat precocious. Being the only son of a widowed and extremely wealthy father, he was also rather spoilt—at any rate by British standards—and his relationship with his father was a complex one which, until now, had defied her efforts to analyse it. But Joey was a charming little boy and he had been a model patient, Elizabeth reflected indulgently, realising suddenly how fond she had become of him. Too fond, perhaps, for a mere locum tenens in a medical practice for which, very soon, her responsibility would be at an end . . .

She stifled a sigh. It might help Dr. Naylor to decide on future treatment if she were able to find out the cause of today’s attack. She took her stethoscope from her bag and, seating herself on the edge of the bed, helped Joey to unbutton his pyjama jacket. Her brief examination completed, she unclipped the earpieces and asked, with assumed casualness, ‘Nothing happened to upset you, did it, Joey? At school, perhaps?’

He shook his tousled fair head, his blue eyes meeting hers in puzzled innocence. ‘Not a thing. I quite like school now. I used to think it was kinda crummy, but the guys are all right. Say, c’n I sit up now?’

‘Yes, if you like.’ Elizabeth put an arm about the boy’s shoulders and, with her free hand, plumped up the pillows to give him support. ‘You’re quite sure that nothing upset you?’

‘Yeah, I guess so,’ Joey confirmed, but his tone was a trifle lacking in conviction and, sensing this, Elizabeth persisted, ‘You didn’t do anything to annoy your father, I suppose?’

This time his headshake was emphatic, admitting of no doubt. ‘Rile him, you mean? Why would I want to rile my dad?’ He spoke scornfully. ‘Anyway, he’s hardly been here all week. He had to go to Germany part of the time.’

It was true that Joey seldom saw much of his father during the week, Elizabeth reminded herself. Her calls at Ryecroft Manor had been regular and frequent since she had taken over Dr. Naylor’s practice in the small Sussex town of Longmead, eight weeks ago, and in consequence she was familiar with the day-to-day routine of the household. Jason Randolph was the executive head of a London-based American pharmaceutical company and she knew that, each morning at eight o’clock, his chauffeur-driven Cadillac conveyed him to Longmead Station, where he caught the eight twenty-eight express to London. At ten minutes to nine, the same car took Joey to the expensive private day school in Railton at which—provided he was well enough—he remained until four-thirty in the afternoon.

On his return to the Manor, the little boy was looked after by an efficient but somewhat forbidding German housekeeper, Helga Gottfried, who with her husband Walter had been engaged by Mr. Randolph’s firm to run the house for him. They were an odd couple, excellent servants, Elizabeth had to admit, but in her opinion scarcely the right companions for a boy of Joey’s quicksilver temperament and uncertain health. They gave him no affection and were either unwilling or unable to converse with him and—until she had interfered—he had been in their company until six-thirty or seven, when his father got back from London. On the days when his asthma confined him to bed he had spent most of the time alone, for Helga had attended only to his physical needs and it was this which, finally, had driven Elizabeth to interfere.

Greatly daring—for he was not an easy person to approach—she had ventured to express her opinion of the effect that lack of the right companionship was having on Joey to Jason Randolph and . . . her mouth tightened, in remembered resentment. He had listened to her with his usual aloof courtesy but had obviously seen no cause for her anxiety.

‘You’re surely not suggesting that I should get a nurse for the boy, are you, Dr. Manners? Oh, come now, he’s not a baby—he’s six years old! Oh sure, I’m aware that nannies are a British tradition, but I’m not having my son pampered—no, by heaven I’m not! He’s a darned sight too soft as it is.’ He had sounded almost angry, she remembered, as if her suggestion had affronted him, but then, controlling his indignation, he had added, in a more placatory tone, ‘I’m not questioning your professional advice, Doctor. If it’s your considered view that Joey needs somebody younger than the Gottfrieds to be with him when he’s not at school, why, then I’ll have a girl from my office staff come here maybe a couple of days a week to keep him company. Or I’ll hire a tutor for him . . . although he goes to school most days, doesn’t he? It’s only when he gets an attack of asthma that he has to stay home. And aren’t you forgetting Kelly? Kelly’s young and he gets along pretty well with Joey . . . I’ll have Kelly spend more time with him, if you like. But not a nannie—my boy doesn’t require a nannie, Dr. Manners, that I do know.’

He had deliberately misunderstood her, Elizabeth thought, still conscious of a lingering resentment. She had never intended to suggest that he should employ an old-fashioned nannie—it was, in any case, unlikely that he would have been able to find one since, even in tradition-loving England, nannies were a dying race. And as for Kelly . . . oh goodness, he was the last person she would have chosen as companion to a delicate little boy like Joey, the very last!

Elizabeth’s smooth fair brows met in a frown. As a conscientious doctor, she had wanted to resolve the problems which Joey’s case had posed before leaving the practice—he had been the first patient she had seen, and her professional conscience as well as her personal feelings were involved. But the problem wasn’t solved and Kelly, she was convinced, could never be the answer to it.

Kelly—she was never quite sure whether this was his surname or his Christian name—carried out the duties of chauffeur, but he did not wear uniform and he appeared to occupy an unusually privileged position in the Randolph household. The Gottfrieds addressed him as ‘Herr Kelly’; they also took orders from him and cooked his meals, which he ate in the house with Jason Randolph when he was at home, or in a luxurious flat built over the garage if his employer entertained guests or was absent on a business trip abroad. She had once heard Kelly describe himself, on the telephone, as Mr. Randolph’s personal assistant—a claim that was borne out by the fact that he dealt with telephone calls and correspondence, in addition to driving and tinkering with the Cadillac which, she was forced to concede, he kept in an immaculate and highly polished state and drove extremely well.

He was a tall, dark-haired American of Irish extraction possessed of more than ordinary good looks, a magnificent physique and a pair of curiously cold blue eyes which seemed to her a contradiction. Her mistrust of him was, Elizabeth recognised, more instinctive than reasoned, but she hadn’t been able to overcome it. Very soon after making Kelly’s acquaintance she had decided that he was too glib of tongue, too well aware of his own animal attraction and altogether too smooth in manner to be trustworthy. He could turn on all the facile charm of his race at will, whenever he considered the effort worthwhile, quite shamelessly and without scruple, in order to get what he wanted. Precisely what he wanted she had, as yet, no idea, although she suspected that it was some sort of ascendancy over Joey, by means of which he could make himself indispensable to the boy’s father, and thus render his position more secure.

On this account alone she would have disliked him, she thought, because Joey was impressionable and almost pathetically grateful to anyone who took pity on his loneliness or made an effort to talk to him. And Kelly had made considerable efforts during the past few weeks, with the result that now, in the boy’s uncritical eyes, he was a hero who could do no wrong . . . and therein lay the danger. Far from pampering the frail little boy, Kelly was doing all in his power to toughen him—on orders, possibly, from the boy’s father, although that did not entirely excuse him because, at times, he went too far. As he must have done this afternoon . . . Elizabeth glanced covertly at Joey and then, conscious of a sudden, choking anger, lowered her gaze.

If Joey hadn’t annoyed his father—a previous cause of his attacks, as she had discovered—then there was only one possible explanation for the attack he had just suffered. Kelly, who had given him a riding lesson when he got back from school, must have tried his endurance too far and she would have to speak to him about it. Not that speaking to Kelly did much good, she reflected wryly. She had endeavoured to remonstrate with him before on the vexed question of overtaxing Joey’s slender reserves of strength, going to great pains to point out what dire consequences this could have, but he had made it clear, in his insolent, mocking way, that her protests were falling on deaf ears. Despite her degree and her professional authority, Kelly paid only lip-service to the advice she offered and then pursued his own course, treating her warnings with contempt.

A succession of different girls from Jason Randolph’s office had all failed, for a variety of reasons, to provide the kind of companionship Joey needed. Most of diem preferred the bright lights of London and the office work from which they had been somewhat high-handedly removed and, anxious to return as soon as possible to their accustomed environment, none had made more than a half-hearted attempt to win the boy’s affection. And one at least, Elizabeth recalled wryly, had been more intent on winning Kelly’s affections than those of her charge . . . so that what Jason Randolph had been cynically pleased to call her ‘experiment in psychology’ had come to an abrupt end. No more reluctant typists would make the journey from London to Ryecroft Manor and Kelly’s pleased smile, when he had told her that in future Joey’s care was to be entrusted exclusively to himself had been in the nature of a claim to victory.

‘Anyway, Doctor, you’re not going to be here much longer, are you?’ he had suggested, a derisive gleam in the cold blue eyes. ‘When Dr. Naylor gets back, he’ll be visiting Joey and I don’t reckon that he’s the kind to indulge in crackpot theories, like you’ve been doing. Anybody would think the kid was a cripple, the way you carry on about him.’

He was probably right about Dr. Naylor, Elizabeth thought with a pang, and there was nothing she could do about it, nothing at all, because now she . . .

‘Say, Dr. Manners . . .’ Joey’s croaking little voice broke into her thoughts and he asked, as if he had sensed their trend, ‘Do you really have to go away on Sunday?’

She felt a lump rise in her throat. ‘Yes,’ she answered reluctantly, ‘I’m afraid I do, Joey. Dr. Naylor is coming back, you see, and this is his practice. I was only looking after his patients for him until he was well again, after his operation. And now he is, so——’

‘I don’t like Dr. Naylor,’ Joey informed her. ‘He’s an old stuffed shirt. And he doesn’t do a thing when he comes to see me, just claps me on the head and says I oughta eat more.’

While privately sympathising with him, Elizabeth reproved him dutifully, ‘You shouldn’t say things like that, Joey.’

He eyed her miserably. ‘Well, they’re true. I wish you weren’t going away.’

‘So do I,’ Elizabeth confessed. She started to replace her instruments in her bag, suddenly anxious to get the parting over, although she had no reason to hurry. She had done the evening surgery and finished all her outstanding calls, in preparation for Dr. Naylor’s return. He would probably be in the house by this time—they had telephoned from the convalescent home, warning her to expect him soon after eight—but the prospect of spending the rest of the evening in his company held little appeal for her. His sister, who kept house for him, was nice, but Dr. Naylor was . . . what had Joey called him? A stuffed shirt . . . she permitted herself a brief smile, struck by the aptness of this description, and started to get to her feet, but Joey’s small hand caught at her sleeve, pulling her back.

‘Where are you going?’ he demanded huskily.

‘Back to Dr. Naylor’s house. I have to pack.’

‘I don’t mean right now.’ His fingers tightened their grasp on her sleeve and, through its thin material, she could feel how hot they were. ‘I mean Sunday,’ he explained gravely, ‘when you leave Dr. Naylor’s. Are you aiming to do another—what’s it called? Locum something?’

‘Locum tenens,’ Elizabeth supplied, and shook her head. ‘No, not at once, Joey. I shall go home for a week or so first, I expect . . . to Yorkshire, where my parents live,’ she added, anticipating the question. ‘I haven’t seen much of them lately. I was working in a hospital in London before I came here, you see—taking exams—which didn’t leave me much time to visit them.’

‘You couldn’t take me with you, could you?’ Joey asked eagerly. ‘I wouldn’t be any trouble.’

‘Well . . .’ Elizabeth hesitated, hating to disappoint him. Her parents wouldn’t mind, of course—they never minded who she brought home with her and the big, shabby old farmhouse in the Dales was elastic in its capacity to welcome unexpected guests. ‘I’m afraid your father wouldn’t let me take you,’ she said at last, reluctantly, and saw the eagerness fade from the boy’s upturned face.

‘No, I guess he wouldn’t.’ His voice was adult in its resigned acceptance. He had everything and yet he had nothing, Elizabeth thought, and took his grubby little hand in hers, feeling him tremble. ‘Where will you go, after you’ve seen your folks?’ he persisted, and she knew that he was willing her to promise she would come back to him.

‘Well, I have a hospital appointment that I’m due to take up in the autumn—that is, in the fall. Until then, I shall probably fill in time by doing locums for other doctors who need a holiday, like Dr. Naylor,’ she told him evasively, anxious not to drop even a hint that her appointment was to the hospital in West Bengal where, with a team of volunteers from her London teaching hospital, she had spent five heartrending weeks, helping to care for the flood of refugees from East Pakistan at the height of the cholera epidemic in June.

To a child like Joey, India would, of course, seem half the world away and their parting final and irrevocable if she told him her destination, but . . . Elizabeth looked down at him wondering, a trifle wryly, why this one child should matter so much to her that she now regretted her promise to return to Quadrabad. This one well-fed, privileged and protected child ought not to matter, she reproached herself. Had she not watched many other children die, most of them exhausted and starving? Had she not watched, powerless to save them from their inevitable fate, powerless even to alleviate their suffering because the help she and her colleagues had brought them had come too late . . . the lump rose again in her throat.

But perhaps that was why he mattered; perhaps that was why she wanted so much to help him as if, in some way she could not attempt to explain, helping Joey Randolph would make up for those others whom, for all her skill and training, she had failed to help. Aware that she was in danger of betraying her feelings, she again made to rise, but Joey clung to her, sobbing.

‘Don’t go!’ the little boy gasped. ‘Please . . . stay with me, Dr. Manners, just for a . . . just for a while longer.’

Elizabeth heard the tell-tale rasp of his breath, forewarning of another attack and, careful to speak quietly and calmly, she bade him lie still. ‘Take a deep breath, Joey . . . come on, you can. Now another . . . that’s the way. I don’t want to have to give you another injection so soon.’

‘I . . . I’ll try. But you . . . you will stay with me, won’t you?’

‘All right, just for a few minutes, then. But only if you concentrate on breathing slowly and deeply.’ Elizabeth resumed her seat on the end of the bed, subjecting him to a thoughtful scrutiny as, obediently, he tried to do as she asked. But it was a struggle and she knew that she hadn’t yet got to the root cause of his attacks. That they were psychological she was convinced, and the nature of this one added to her conviction. ‘Joey,’ she said, with a swift change of tone, ‘I don’t have to leave Longmead until Sunday evening. How would you like it if I took you to the Safari Park in the morning? Do you think your father would let you come with me, as a—well, as a farewell treat?’

As suddenly as it had begun, the threatened asthma attack petered out; Joey’s breathing returned to normal and the sobs ceased. ‘Oh gee, that would be swell! I’d like it just fine, Dr. Manners, truly I would!’ He was grinning at her in excited delight. ‘I’ll ask my dad the minute he gets home. But he’ll let me go if I’m with you, I’m sure he will. Shall I call you and tell you if he says it’s okay?’

‘Yes, you do that, Joey,’ Elizabeth agreed. ‘And now I really must go or the Naylors will start wondering what’s become of me.’

She left him, smiling, and now he let her go without demur, having achieved his object and postponed their parting. He was just a spoilt, neurotic child, she told herself severely, as she went downstairs—hadn’t she proved it, a few minutes ago? And yet . . . she shook her head. It wasn’t true; every instinct she possessed cried out to her that it went deeper than that. He was spoilt . . . but his problem wasn’t solved and she would have to leave with it unsolved, because there was no more time in which to find the answer.

In the hall, Helga Gottfried was waiting for her, a gaunt, grave-faced woman in a black dress, her grey hair neatly but severely dressed in two coils about her ears. She listened, without change of expression, to the instructions Elizabeth gave her, promised to take a meal up to Joey at once and added, in her correct but heavily accented English, ‘Herr Kelly has just now gone to the railway station to meet the train of Herr Randolph.’

‘I see . . . well, perhaps you’d be kind enough to tell Mr. Randolph, when he comes in, that I have given Joey an injection and that he is now perfectly all right. If he wants to speak to me, I shall be at Dr. Naylor’s . . . he can telephone me there.’

The housekeeper inclined her head. ‘Very good, Doctor.’ She accompanied Elizabeth to the door and stood politely on the steps until the visitor had climbed into her car, then, with a stiff little bow, she vanished, the heavy front door closing behind her.

Dr. Naylor had returned when Elizabeth re-entered his small, comfortably furnished house in Longmead’s main street and, at his invitation, she occupied the time before their evening meal by giving him a report on the patients she had seen and treated during his absence. She had been careful to keep her case-notes and call lists up to date, and since these were all filed ready for his inspection, her report did not take long, and they both responded at once to his sister’s call that supper was ready.

Conversation over the simple but well cooked meal was of local affairs and patients, after which Dr. Naylor launched into a detailed and occasionally critical account of his treatment in the famous London hospital to which he had gone for his operation. He had, however, nothing but praise for the convalescent home he had just left, and when coffee was served and he continued on this topic, Elizabeth exchanged a surreptitious glance with her hostess and excused herself, on the plea that she had packing to do.

‘Of course, my dear—off you go,’ Gertrude Naylor bade her readily. ‘And take the coffee tray up with you, if you like . . . we shan’t want any more. Anyway, I think Edward ought to have an early night, don’t you, because he’ll be back in harness tomorrow.’ Her brother offered a half-hearted protest and she smiled, taking Elizabeth’s arm to walk with her to the hall. Satisfied that he could no longer hear what she was saying, she went on, ‘I’ll pack him off, don’t worry . . . in plenty of time for us to watch that play on ITV, so come down when you’re ready, Elizabeth. Oh dear!’ Her plump, homely face clouded over. ‘You know, I am going to miss you terribly when you leave us, I really am . . . and it’s the first time I’ve ever said that about one of my brother’s locums, so you can take it as a compliment!’

‘It’s sweet of you to say so,’ Elizabeth began, reddening, ‘but honestly, Miss Naylor, you——’

‘I mean it,’ Gertrude Naylor put in warmly. ‘It’s been lovely having you and, quite apart from the wonderful way you’ve coped with the practice, I’ve enjoyed your company more than I can tell you. It’s been almost like having a favourite niece to stay and I do hope that you . . .’ She broke off at the sound of a car drawing up outside followed, a moment later, by the shrilling of the doorbell. ‘Goodness, who can that be?’ she exclaimed and, crossing to the window, peered shortsightedly through it. ‘I think it’s Mr. Randolph’s car, Elizabeth . . . yes, there’s that good-looking young man who always drives it. Do you suppose he wants to speak to you or to my brother? You called on the little Randolph boy this evening, didn’t you?’

‘Yes, I did,’ Elizabeth confirmed, frowning in some perplexity. If Joey had had another attack, presumably his father would not have wasted time by sending Kelly to fetch her—he would have telephoned. ‘I’ll see what he wants,’ she offered and, with Gertrude Naylor hovering with unconcealed curiosity at her elbow, went to open the front door.

Kelly, as always dressed with casual elegance, stood on the doorstep. He greeted her with exaggerated politeness—no doubt put on for Miss Naylor’s benefit, she thought uncharitably—and after apologising for the lateness of his call said, still apologetically, ‘Mr. Randolph wondered if he could have a word with you, on a matter of some importance, Dr. Manners. He asked me to tell you that it wouldn’t take long and’—he gestured towards the gleaming Cadillac—’he figured it might save time if I ran you out to the house and waited to take you back.’

‘Well, I suppose if it’s important . . .’ Elizabeth stared at him, puzzled as much by his manner as by the unexpected invitation from Jason Randolph who, in all probability, only wanted to explain why he couldn’t give her permission to take Joey to the Safari Park next day. Although perhaps . . . ‘Is Joey all right?’ she asked, her tone more brusque than she had intended.

Kelly grinned, the familiar mocking gleam in his eyes as they met hers. ‘Oh sure, Joey’s fine—tucked up in bed asleep.’ He moved, with long-limbed grace, towards the car. ‘Are you coming?’

Elizabeth hesitated and from behind her Gertrude Naylor whispered encouragingly, ‘I expect Mr. Randolph wants to thank you for all the trouble you’ve taken with his little boy. I think you should go, my dear—and don’t worry about your packing. I’ll do it for you. I always do Edward’s and he says I’m quite good at it. If there should be a call that can’t wait until you get back, I can telephone you at the Manor.’ She added, emphasising her words with a gentle push, ‘It’s nice to be thanked sometimes, you know. So often people aren’t a bit grateful to their doctors, however much is done for them.’

Which was true, Elizabeth thought, only somehow she did not anticipate thanks from Joey’s father, who had always struck her as a man who believed that money was sufficient recompense for any services rendered . . . and the account for hers, when this was sent in by Dr. Naylor, would be a fairly large one. She bit back a sigh and obediently went out into the street. Reaching the car, she saw that Kelly was holding its rear door open for her, but he waved a casual brown hand in the direction of the passenger seat in front.

‘You care to sit with me, Doctor?’ he enquired. ‘There’s no extra charge, if you do. And I guess we could talk a whole lot better if I don’t have to keep twisting my neck around to listen to you.’

He had reverted, in the absence of an audience, to the halfbantering, half-derisive tone he normally used to her and she wondered, regretfully, how anyone who looked as attractive as he did could be so . . . so odious. ‘If we have anything to talk about,’ she returned icily, and had the satisfaction of seeing his grin momentarily fade.

‘We have one subject in common, don’t we?’ he demanded, recovering himself quickly. ‘I reckon we could argue about Joey most of the night . . . although I wasn’t intending to argue with you. To be honest, I thought you’d want to know what happened at the riding school this afternoon.’

Elizabeth climbed into the passenger seat with what dignity she could muster and, as he got in beside her and switched on the engine, she said quietly, ‘Personalities apart, I would like to know what happened. You see, Joey had a very bad attack and——’

‘I know, I saw him,’ Kelly put in with what, for him, sounded like concern. ‘Poor little kid . . . it turns me up to see him gasping for breath the way he does. But all the same . . .’ He left the sentence uncompleted. Leaving Longmead’s main shopping centre, the powerful car gathered speed and Kelly added, more to himself than to her, ‘I said I wasn’t going to start an argument with you and so help me, I won’t.’

‘Well, what did happen at the riding school?’ Elizabeth asked, matching his restraint. ‘I’d be grateful if you’d tell me.’

He shrugged. ‘That’s just it, Doctor—nothing, really. I took Joey for a cross-country ride, nice and quiet, you know . . . and I picked a well-mannered pony for him, so he’d have no trouble. We popped over one or two gaps and small fences and he was doing fine, enjoying himself and managing the jumps pretty well. When we got back, I asked him if he’d like to try going round the school-fences in the paddock and he said he would, if I’d give him a lead. He was following me along when suddenly I heard him let out a yell. I looked back over my shoulder and I saw his face—it had gone all white and scared, with the sweat pouring off it.’ He hesitated, a frown drawing his dark brows together, and Elizabeth prompted, quite gently, ‘What did you do?’

Kelly repeated his shrug. ‘I went on, of course,’ he said, his tone defensive. ‘What else could I do, for God’s sake? I couldn’t let him flunk out, with his old man for ever telling me that he’s a big boy now. The next thing I knew, the pony had refused and Joey was clinging on round its neck, sobbing his heart out and gasping for breath.’

‘You could have pulled up,’ Elizabeth told him reproachfully. ‘You could have given him a chance to recover, surely, instead of just going on. You——’

‘There you go again!’ Kelly complained. ‘Making out it’s my fault—I ought to have known you would. Well, this time it wasn’t my fault, Dr. Manners. The kid was just plain, old-fashioned scared and he covered it up by having himself an attack of asthma . . . which rather debunks your theories, wouldn’t you say? He comes up against something that scares him—or something he feels he can’t face up to—and bingo! He starts puffing and wheezing and carrying on, and you rush around, accusing me or the Gottfrieds of roughing him up. Do you honestly think you’re being quite fair to us?’

Perhaps, she wasn’t, Elizabeth told herself, and said, quite mildly, ‘There has to be a reason for his fear, don’t you see? With a hypersensitive child like Joey, who has too much imagination, you can’t force him to stop being afraid. It only makes him worse if you do, and compels him, because he has no other defence, to take refuge in an asthma attack. But he does that subconsciously and he couldn’t prevent the attack now if he tried. In my opinion—that is, my professional opinion—it is essential that we should try to understand his fear and free him from it, by removing the cause or causes. That’s what I’ve been trying to do.’

‘It can’t be done,’ Kelly said with conviction. ‘Fear’s a thing you can’t cure, believe me.’ He spoke with bitterness and, a trifle startled, Elizabeth turned in her seat to look at him. ‘I’m speaking theoretically,’ she began, ‘but——’ Savagely he cut her short, his good-looking face oddly white and tense beneath its coating of healthy tan.

‘Hell, you’re all theories, aren’t you?’ he flung at her. ‘What do you know about fear? I’ll bet you’ve never been scared in your whole blameless life, Doctor Elizabeth Manners! Well, I have, see, so I know what I’m talking about. I’ve been so scared that my guts turned to water . . . and not just for a few minutes, not even for a few days, but for weeks on end. And I didn’t have any out—I could have had asthma attacks until I was blue in the face and they wouldn’t have done me any good. Take my word for it—I know what it is to be afraid. I really do know.’

He had never spoken to her so frankly before and, suddenly sensing the pain that was in him, Elizabeth put out a hand to touch his as it gripped the wheel. He was a veteran, she remembered; Jason Randolph had mentioned it once. ‘Where was this?’ she asked. ‘In Vietnam, Mr. Kelly?’

‘Why don’t you just call me Kelly, like the rest?’ he demanded accusingly. ‘Yeah, it was in Vietnam.’ He brushed her hand aside, as if contemptuous of the small gesture of conciliation she had attempted to make, his gaze fixed on the road ahead. ‘You want me to tell you about it?’

‘Well, yes, if it would . . . if you feel you can, Mr . . . I mean Kelly.’

‘So you can apply your theories to me?’ Kelly suggested wryly.

She shook her head. ‘No. But sometimes it helps a little to talk about it.’

He gave her a swift, sidelong glance, easing the pressure of his foot on the accelerator as they approached the Manor gates. Turning into the long drive, he slowed down almost to a crawl. ‘I don’t talk about it usually, not to anyone,’ he said. ‘I want to forget the whole God-awful thing. But you’re going away and I don’t reckon we’ll see each other again, do you? So . . . you ever hear the term “fragging”, Doctor?’

Elizabeth frowned. She had read an article quite recently, in one of the newspapers, about the effects of drug-taking among American troops in Vietnam, she remembered, and there had been something about fragging in that. It . . . memory returned and she answered, ‘Yes, I think so. Doesn’t it mean that soldiers who are afraid of going into battle shoot their commanding officers, so that they can’t be ordered to fight?’

‘Yeah,’ Kelly confirmed. ‘That’s what it means, more or less. It’s another word for murder. Sometimes it’s a bullet in the back, sometimes it’s a grenade, rolled under the guy’s bed or lobbed into his quarters when there’s nobody around to see where it came from. Whatever way it’s done, the result is the same. An officer, who’s been trying to do what he was sent out there for and win the war, gets killed or maimed and his company or his platoon don’t have to fight. They can stay alive and keep on hoping that the next officer who’s posted to them is as scared as they are, and not what they call a “glory hunter”, who’s liable to take chances with their lives. If he is, then he gets the same treatment and so it goes on.’

‘But that is murder!’ Elizabeth exclaimed, shocked by the weary cynicism in his voice. ‘How can they go on doing it? Surely they must——’

‘Be found out, you mean? No.’ His headshake was emphatic. ‘The whole bunch are in it together and no one can prove a thing, if they all stick to the same story. All they have to worry about are their own consciences, and after a while out there, you get too scared and too demoralised—or too hopped up—to have a conscience. You . . . oh, what the hell!’ Kelly broke off abruptly. He was silent for so long that Elizabeth, nerving herself to ask the question, ventured uncertainly, ‘Did you—Kelly, were you so scared that you shot your commanding officer?’

‘Good grief, no!’ He turned on her, his blue eyes blazing beneath their level dark brows. ‘It takes a junkie to do that and, whatever you may think of me, I’m no junkie. I’ve even got a conscience, but you’ll have to take my word for it.’

‘I . . . I’m sorry.’ She had hurt him, she realised, and was instantly contrite. ‘Then what—why . . . I don’t under stand——’

‘It’s simple,’ Kelly stated flatly. ‘I was one of the two hundred or so officers who were fragged. One of the lucky ones, I guess—I only got shot in the back and I survived. My platoon sergeant, who was the real glory hunter and the bravest guy I ever knew, the one who kept me in line . . . they gave him a grenade under the bed and there wasn’t enough left of him to identify. He’d saved their hides I don’t know how many times, when they were green rookies, but they killed him just the same. And my second-in-command, a kid of nineteen I was supposed to be training . . . he had his head blown off from behind, the first time he went into combat.’ He let out his breath in a long, rasping sigh. ‘Both of them went before me. After they’d gone, I had five long weeks, waiting, just waiting, knowing what was coming to me next time we were ordered into the combat zone . . . if I didn’t let that bunch of so-called soldiers I was supposed to be commanding have it their own way and flunk out. You just don’t know what fear is, Dr. Manners, until you learn to be more afraid of the guys in your own outfit than you are of the enemy. That’s why I . . . oh, for God’s sake, I don’t know why I’m telling you all this! I suppose I want you to understand—but you can’t, can you? You can’t even begin to understand.’

‘I am trying to. But I . . .’ To her own surprise, Elizabeth felt tears in her eyes and her voice wasn’t steady as she added, ‘Thank you for telling me. I—I’m glad you did.’

‘You are?’ His tone was cynical again. ‘I guess I was prompted by my own conceit. I didn’t want you to go away, wherever you’re going, with too low an opinion of me, or to imagine that I’m being hard on Joey, because I’m not. What I’m doing is for his own good and I believe that, just as firmly as you believe in those theories of yours.’ They came in sight of the house and Kelly swung the big car expertly into the semicircular stretch of gravelled drive which led to the front door, pulling up outside it with a flourish. He did not immediately get out to open the car door for her and Elizabeth waited, grateful for the opportunity to compose herself before her interview with Jason Randolph.

She had misjudged Kelly, she thought unhappily, and as a result had been less than fair to him. She started to say so and to offer him a belated apology, but he waved her to silence. ‘Save your breath, Doctor—you don’t have to apologise to me. It’s kind of late for us to start handing out olive branches to each other, isn’t it? Pity—we could maybe have made something of Joey between us, if you didn’t have to leave here. You, with the soft and gentle touch, acting as the antidote to what I’m trying to teach the poor little kid. But that’s the way it goes, I guess.’

‘Yes, I suppose it is,’ Elizabeth conceded regretfully, still feeling guilty on his account now, as well as on Joey’s. Although perhaps Joey . . .

‘At least quit worrying about him,’ Kelly urged, as if he had read her thoughts. ‘Sure, I know you’re fond of the kid. Well, so am I, in my own way, and I’ll do the best I can for him, I give you my word. All right . . . no hard feelings?’

He was offering her the next best thing to an olive branch, she realised, and for Joey’s sake, she must accept it—albeit with reservations. What he had told her of his experiences in Vietnam made him even less suitable as a companion for Joey than she had originally thought . . . but the matter was out of her hands and there was nothing she could do about it except, perhaps, drop a carefully veiled hint to Dr. Naylor.

‘No, no hard feelings, Kelly,’ she echoed, meaning it.

‘Good!’ He eyed her with his usual mockery, but he was smiling. ‘What I’ve just said is not to be repeated, you understand—not to anyone. The Great White Chief in there’—he jerked his head in the direction of the lighted window of Jason Randolph’s study—’doesn’t know a thing and I don’t want him to, not now, not ever. I aim to keep this job. It may not seem like much of a job to you, but it pays all right and it suits me, see? So not a word to my boss. I want your promise on that, before I let you out of here.’

‘He’ll hear nothing from me,’ Elizabeth assured him.

‘Thanks, Doctor.’ Kelly leaned across her to open the door on her side of the car, his hand—whether intentionally or inadvertently she did not know—brushing against her bare arm and sending a small thrill coursing through it, from wrist to elbow. ‘I’ll be around when you want to go back. Just say the word.’

She nodded and, bracing herself, got out of the car and crossed stiffly to the front door, pausing for a moment before ringing the bell.

CHAPTER TWO

Jason Randolph was seated at his desk when Elizabeth was shown into his study by the taciturn Walter. He looked up with a welcoming smile and thrust the papers on which he had been working into an open briefcase at his side. ‘Ah, good evening, Dr. Manners! It’s very good of you to come out here again at this late hour.’

He came to meet her with extended hand, a tall, commanding figure in well-cut dark brown slacks and a lemon-coloured shirt of the leisure-wear variety, open at the neck and worn with a loosely knotted silk scarf in lieu of a tie. The casual clothes and their fashionably subdued colours enhanced the smooth bronze of his skin, although this, Elizabeth was aware —since he had once, in a moment of expansion, confided the fact to her—was the result of regular exposure to the artificial rays of an ultra-violet lamp.

‘I don’t have time to take exercise in the sun,’ he had told her in explanation, ‘or to play games any more—I wish I did. So I have to make do with my sun-lamp, massage and twice weekly sessions at a gym, followed by a sauna bath. I figure it’s important to keep fit in my job . . . and to avoid putting on weight, of course. They work, but they’re substitutes for the real thing, aren’t they?’