39,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

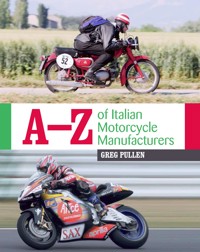

Italian motorcycles have a place in history - and many enthusiast's hearts - out of all proportion to the numbers that been built. If the number of motorcycles built by Italian manufacturers is small, the sheer number of Italian motorcycle factories will surprise readers. A-Z of Italian Motorcycle Manufacturers is the most complete directory of Italian motorcycles available today. In addition to covering the most famous Italian factories, this is a definitive guide to the marques that have had little or no coverage. Some might be familiar, while others are remembered for their racing achievements, and many will never had been heard of by most readers. This new book includes: entries for every marque where it was possible to establish when and where the factories were active; details of the most important motorcycles each manufacturer built, and the marques' greatest achievements; the history of the once great factories and finally, an appendix lists the other, less well-known manufacturers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

A–Z

of Italian MotorcycleManufacturers

GREG PULLEN

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

Paperback edition 2018

© Greg Pullen 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 488 9

CONTENTS

Part 1: INTRODUCTION

Part 2: A–Z OF ITALIAN MOTORCYCLE MANUFACTURERS

Appendix –Those Who Also Served

Index

Part 1

INTRODUCTION

The centre of Bristol was for many years given over to Italian cars and motorcycles. In the foreground is an early Laverda 750 twin with drum brakes. Behind it is a 900cc (actually 864cc) GTS Ducati, probably the most reliable of the bevel twins.

Italian motorcycles are revered out of all proportion to the numbers actually built. If you exclude sub-125cc machines and post-Cagiva-era Ducatis, only a few thousand of even the most successful models were built, compared to the tens of thousands that British manufacturers produced. Even today, the big four – Aprilia, Ducati, Moto Guzzi and MV Agusta – produce tiny numbers of motorcycles compared to the Japanese. Yet I would wager that as many people would recognize those Italian brands as would know the Japanese big four. That Ducati, in particular, are able to compete with the Japanese across the board is incredible given their size. Yet on racetracks and in road tests across the world, the Italians are rarely ‘also rans’. A Honda executive told me a few years ago that Honda is in MotoGP to sell millions of mopeds and scooters in the Far East. Ducati do not sell any small motorcycles, let alone mopeds, and consider building over 50,000 units a year, cause for celebration. As someone at the factory said: ‘When we win at racing, it is like everybody who works here is being given a big red parcel as a present’. The Italians can be absolutely ruthless business people, but with motorcycle manufacturing it is always more than that.

Part of this must be that overused word – passion. While top management is often dispassionate and focused on the bottom line, the same is rarely true of the people on the production line. I have been fortunate enough to visit the Moto Guzzi, MV Agusta and Ducati factories, and the enthusiasm on the factory floor is astounding. Italian motorcycles are usually built by people who believe they have one of the best jobs in the world, even if at times – especially during the 1970s and 1980s – there has been friction. But then, that was also true in England.

Moto Guzzi was one of the first manufacturers to offer rear suspension, operated via springs below the engine. Behind is a Morini, Aermacchi and (behind that) a rare Morini 350cc with 1980s’ rather slab-sided styling.

The Aguzzi referred to in the main text. Ridden from Italy, which sounds an achievement until you discover that hub-centre steering legend John Difazio walked.

The other thing about Italian motorcycles is the number of people who have wanted to build them. Initially, I expected to list well under a hundred marques, but quickly discovered there are mentions of almost 600 in Italy. And those were just the people who made formal and recorded plans: many others with a workshop must have looked at one of the many engines on sale as a standalone unit and thought about building a motorcycle. After all, the first TT-winning Norton had a Peugeot motor. Add to that the fact that, historically, Italy has always made fantastic motorcycle components – think Borrani wheels and Brembo brakes, for example, the latter often fitted to the best Japanese motorcycles. Indeed, when Gerald Davison, the first non-Japanese director at Honda, was running the NR500 ‘oval’ piston grand prix project, he was frequently frustrated that Honda Racing Corporation could not build small components as good as those he could buy off the shelf in Italy. So, new manufacturers found it easy to set up shop, if not stay the course. Many of the manufacturers survived only a year or so, leaving no record of the motorcycles they built. These are listed in the Appendix; but when the years a manufacturer survived, the region they were based in and some details of the motorcycles they built could be established, then they are listed in the main text.

Other manufacturers turned to motorcycle production out of the simple need to protect jobs and wealth creation when the allies forbade them to continue building military equipment after the Second World War. Chief among these are Aermacchi and (MV) Agusta, who have since returned to aircraft production. Even the Vespa scooter was created for the same reason.

Readers may notice that many companies failed in the run up to the Second World War, and that there are an awful lot of 175s. Both are related to the rise of Mussolini’s Government: manufacturers that fell from favour found themselves put out of business, and 175s were given huge tax breaks to ensure affordable transport was provided alongside larger motorcycles, which were still largely a hobby for the wealthy. 175s could also be ridden without a licence or insurance. Ironically, it was the post-war swing from fascism to communism that would push Ducati into motorcycle production. It is important to realize how quickly attitudes in Italy changed, swinging after many years of Fascist and Nazi rule to communism almost overnight. When finally liberated in April 1945, the people of Bologna initially took the Ducati brothers off to face a firing squad, proof of how divided the country had become. Bologna city council actually sent a Ducati 900SS to Fidel Castro as a gift, and it now sits in a museum in Havana having clearly been ridden.

Tax and licencing breaks made 175cc motorcycles incredibly popular in Italy, including for racing. This is a MDDS (macchine derivate di serie), which was a sportier but still production machine eligible to compete in Formula 3 racing and production classes in events like the Motogiro.

Italy has very few natural resources, although it does have healthy deposits of bauxite, from which aluminium can be extracted. Post-war especially, the poverty of subsistence farming quickly gave way to commuting to factories that sprung up to make anything that might create work and exports. A nation used to a short walk into the fields suddenly needed a means of reaching towns and cities, where they might find work, leading to a boom for anybody who could sell them cheap transport. Again, the rules on who could ride anything below 175cc were almost non-existent, meaning this as the capacity many manufacturers focused on. It was also the reason that the famous Motogiro races, touring the public roads of Italy, limited riders to motorcycles of no more that 175cc.

And this is very much the A–Z of Italian motorcycles. There are no scooter manufacturers listed, unless they also produced motorcycles. And those manufacturers who only made sub-50cc mopeds are also absent. The vast majority used the same Franco Morini or Minarelli two-strokes, and were almost indistinguishable from one another. Given that there were perhaps 200 of them, they too have been omitted, unless they were especially important to the UK market or part of the range of a motorcycle manufacturer.

The year that manufacturers were established is also difficult to address with certainty. Whilst Moto Guzzi started as a motorcycle manufacturer, many did not. Early pioneers might have started out as bicycle manufacturers, as did Bianchi, taking the obvious step into building motorcycles when the internal combustion engine came along. Ducati had nothing to do with complete motorcycles until the communists had ejected everybody with the Ducati name from the business. Despite Ducati celebrating ‘90 years of excellence’ in 2017, it was actually 1948 before a complete motorcycle bearing the Ducati name was sold. I have tried to make it clear in the text when a firm built its first motorcycle, while putting the year the business was established – regardless of what that business was – in the heading. So the founding date I have given for Ducati is 1927, and I have tried to apply this policy throughout.

And, finally, a caveat on completeness. The occasional periodical I publish, Benzina, had a reader send a photograph of an Aguzzi that is reproduced here. During a lunch break amble he had stumbled across the bike in 1985, chained to railings in London’s Little Venice. A connoisseur of Italian lightweights, he persevered with notes through letterboxes until he found the owner, an Italian waiter. Despite the little fifty being unregistered, he’d apparently ridden it over from Italy about eighteen months previously. Filled with good intentions, my reader paid £25 for the Aguzzi and stuck it at the back of his garage.

With little to go on, apart from ‘Ducati’ stamped on various components, and the Franco Morini engine labelled ‘no3’ presumably reflecting the three-speed hand-change gearbox, I approached dating specialist Stuart Mayhew. He has a treasured old book that includes a census of all motorcycle registrations by region in Italy but it had no mention of Aguzzi. Yet he had come across others in Italy as proprietor of Morini specialist North Leicester Motorcycles, so it is not a one-off.

The engine is by the nephew of Moto Morini founder Alfonso, Franco Morini. He started building engines in 1954, and the business grew quickly to make him the market leader in the production of small but powerful two-stroke engines. But all that really tells us is that the Aguzzi is 1954 or later.

The Ducati name is a red herring: Ducati is a common enough family name and appears on plenty of manufactured goods in Italy, and by 1955 Ducati had barely started building complete motorcycles.

So, Aguzzi was probably a dealer, engineer or even a blacksmith hoping to join the big time: unlike the British bike industry, where everything was made in-house, the Italians bought-in pretty much everything, so setting up as a motorcycle manufacturer was comparatively straightforward. The headlight fittings have shades of Meccanica Verghera (MV) lightweights, and the frame design definitely nods towards Ducati’s 98; beyond that nothing is known, so it cannot get an entry in the main text of this book. But it is an admission that while this should be the most complete A–Z of Italian motorcycles in print, there will be marques omitted that never got beyond building a handful of motorcycles before disappearing without trace. Aguzzi was one of them, but at least gets listed in the Appendix at the end of this book.

The other thing that made starting a motorcycle manufacturing business easy, at least until the Japanese came along with their mass production and economies of scale, was that it was often very easy to buy in complete engines, the most complex part of a motorcycle. It is also clear what a strong link the Italians used to have with Britain, regularly using JAP, Blackburne, Rudge Python and Villiers’ engines. From Germany came Sachs and Küchen engines. From France there were Chaise and Train. Within Italy, too, there were the hugely popular Minarelli and Franco Morini small-capacity, two-stroke singles, as well as, later on, Villa. In the pre-war period, small manufacturers would often sell engines along with complete motorcycles, and those engines could find their way into boat or farm machinery. Indeed, Ducati very nearly gave up motorcycle production around 1980 to become a diesel engine manufacturer.

Laverda’s mighty Jota was named in England by Roger Slater – the Italian language doesn’t feature a letter J. The 3-cylinder engine in the Benelli Tornado Tre was originally intended for a new Laverda.

So, of those that follow, this is a reference to each Italian motorcycle manufacturer in turn, with a brief history of how each started out, their most important (if not always most successful) models and their place in history, including racing achievements. There will be few starting with J, K, W, X or Y because those letters are not in the Italian alphabet, which might be a surprise for fans of Laverda’s Jota. It is also the reason that the German ILO engines, which many manufactures used, are usually correctly identified, even though the company’s logo stylized the initial I to look like a J, meaning that many records describe them as Jlo.

Some marques will be familiar, others never before mentioned in print, in English at least. All, I hope, are interesting and an insight into a country still obsessed with motorcycles and racing them as often as possible.

Finally, a thank you to those who allowed their photographs to be used, most especially Vicki Smith, Mykel Nicolaou and Made in Italy Motorcycles. Thanks also to the Bonham’s motorcycle team and others who were able to fill in the gaps in my research and archives.

Part 2

A–Z OF ITALIAN MOTORCYCLEMANUFACTURERS

ACCOSSATO (1973–89)

Founded by Giovanni Accossato in Moncalieri, near Turin. It produced 50, 80 and 125cc off-road motorcycles that won a world championship, three European championships and twelve Italian championships. They still offer motorcycle accessories, especially for racing.

ADRIATICA (1979–80)

Agricultural equipment manufacturers Giuliano and Alvaro Vernocchi established a road racing team and commissioned famed two-stroke engineer Jan Witteveen to build them a 250cc tandem twin in a Bimota frame under the Adriatica banner. This was followed by a V-twin version raced by Randy Mamola and Walter Villa that would be the basis of Witteveen’s work for Aprilia. Financial considerations persuaded the Vernicchis to abandon the project at the end of the 1980 season.

AERMACCHI/AERMACCHI HARLEY-DAVIDSON (1945–78)

Founded in 1913, Aeronautica Macchi – quickly abbreviated to Aermacchi or Macchi – was handily located on the shores of Lake Varese in the north of Italy to specialize in seaplanes. They raced against the British Supermarine S4, 5 and 6 (the forerunner of the Spitfire) in the Schneider Trophy challenges of the 1930s in legendary competitions. Aermacchi went on to build Italy’s finest Second World War fighter plane, the C205 Veltro.

This is the old Aermacchi factory, now home to Cagiva and MV Agusta. Its lakeside setting allowed seaplanes to be tested and the factory was clearly once hangars.

Demilitarized in the post-war era, Aermacchi – like so many other Italian aircraft companies – entered the motorcycle business, aiming to ride the wave of demand for cheap two-wheelers. Its first designer was Lino Tonti, later to become famous for his work at Paton, Bianchi and, especially, Moto Guzzi. Tonti’s stay at Aermacchi was brief but important, partly because he recognized the value of Aermacchi’s wind tunnel. Yes, it was Aermacchi, not Moto Guzzi, who were the first motorcycle manufacturer to use a wind tunnel.

From 1945, Aermacchi built a 500cc three-wheeler, the MB1, aimed at the small truck market. Their first motorcycle was Tonti’s 1951 two-stroke 125 Cigno (Swan), which had a folding dummy fuel tank to allow it to be ridden as a scooter or a motorcycle. Like many of Tonti’s designs, the cylinder was horizontal and, from 1952, doubled up to create a 250cc twin. Despite these advances, in 1955 Tonti was replaced with the ex-Alfa Romeo and Parilla designer Alfredo Bianchi. His first product was the fully enclosed Chimera, powered by a 175cc overhead-valve engine, looking very similar to Tonti’s work, with a horizontal cylinder and unit construction. This was not commercially successful but, when shorn of its bodywork to become the 175 Ala Rossa and 250 Ala Verde, a successful formula evolved based on Bianchi’s principles of light weight, compact construction, simplicity of design and ease of maintenance. Like Rolls-Royce he was only concerned with producing a power output, as he put it, ‘sufficient for the task in hand’.

The styling on Aermacchi’s Chimera 250 gives away the firm’s aeronautical past and access to a wind tunnel. KLAUS NAHR

A competition version of the Aermacchi-Harley-Davidson 250 Al’Oro raced by Angelo Tenconi in 1968. KLAUS NAHR

By 1957, these sporting models had established the Aermacchi blueprint of a spine frame with an underslung horizontal pushrod single that would last right up until 1973. The racing Aermacchis grew directly out of these humble street bikes, as much to reduce expense as for marketing reasons, but they worked. The company’s fortunes took a big leap forward in 1960 when Harley-Davidson bought 50 per cent of Aermacchi, requiring them to build small-capacity ‘Harley-Davidsons’ for the US market, to fight their British and, soon, Japanese competitors. By the mid-sixties, over 75 per cent of Aermacchi production was being shipped to the US.

Because Harley went racing under American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) rules, they also wanted a 250cc road bike that they could tune. So, Aermacchi’s first out-and-out racer was actually developed for short-track racing in the US. Known in America as the Sprint CRS (for dirt racing) or CR-TT (road racing), they were fitted with magneto ignition rather than the 6V battery and coil of European models. Elsewhere it was known as the Ala d’Oro (Gold Wing), the prototype debuted by Alberto Pagani in the 1960 German Grand Prix.

Results were encouraging, and so the first run of production racers was built for the following season, with a 350cc version (dubbed the ERS in the States) following in 1963. These early racers were none too reliable but, in 1966, a revamp brought a stronger five-speed engine producing more power, more reliably. The uncertain handling of the earlier bikes was also resolved with the introduction of a redesigned chassis with a forged tubular central beam. In this guise, the 350 Aermacchi usurped the British Manx Norton and AJS 7R as the machine of choice for the dedicated privateer, weighing a third less and being only slightly less powerful. But the Italian bike’s unit construction engine, lower centre of gravity and considerably smaller frontal area, more than made up for this and, although the Aermacchis were never fast enough to seriously test the works Honda, MV and Benelli fours, they still met with considerable success at grand prix level, as well as winning countless national titles. Aermacchi’s rider, Renzo Pasolini, finished a strong third in the 1966 350cc World Championship, behind Hailwood’s Honda six and Giacomo Agostini’s MV Agusta triple, a feat repeated in 1968 by Aussie privateer Kel Carruthers behind Agostini and runner-up Pasolini, by now beginning his term at Benelli. Although Aermacchi never won a grand prix, there were several second places, including in the 500cc class, in which the bikes competed by dint of overboring to stretch the capacity from 344cc to first 382cc, then 402cc and finally 408cc.

After the Second World War, Harley-Davidson had built their own 125cc two-stroke, the Hummer, based on the same DKW design BSA had also been gifted for the Bantam as part of war reparations. By the 1950s they needed a replacement and knocked on doors across Europe to find a lightweight manufacturer to help them out. Most factories already had loyalties stateside, so Aermacchi was almost Hobson’s choice. Initially, the bikes were rebadged existing designs but that changed when Harley took full control in 1974.

Inevitably, the two-stroke revolution had come to Varese, and the advent of Yamaha’s production racers especially was matched by Aermacchi’s own two-stroke motors and early success with Pasolini, newly returned to the fold. In 1974, Harley then bought the remaining half of Aermacchi’s motorcycle business, allowing Macchi to focus on their renewed interest in aircraft.

A fine collection: in the foreground is one of Aermacchi’s attempts to hold back the Japanese two-stroke racing machines: a liquid-cooled 125cc. KLAUS NAHR

Incredibly versatile, the Aermacchi single was sold as a racer, a sporting roadster and a small cruiser-like version.

An Aermacchi in all but name, the Harley-Davidson RR 250 and 350s were developed and built in the old Aermacchi factory.

Harley-Davidson intended to get serious about lightweight motorcycles and the European market. Harley could see what the British had missed – that the Japanese weren’t going to be happy building small-capacity motorcycles, and were creating a new generation of riders who would start with one manufacturer’s lightweight and then stick with the badge on the tank as they climbed the capacity ladder. So Harley wanted a first rung on their ladder and some credibility with a Woodstock generation who didn’t get the tough loner image their post-war fathers had craved. Rockers, Angels and black leather were now for a hard-core minority: the rest of the world was in glorious Technicolor, and meeting the nicest people on a Honda. Harley could see the nearly men in Aermacchi’s race shop just needed cash and encouragement to be winners. If the old Aermacchi factory could also create a range of two-stroke road bikes to bathe in the race shops’ reflected glory, Harley felt they had a plan to conquer Europe and the lightweight market in the US.

Although the two-stroke racers and road bikes were funded by Harley-Davidson, they were really Aermacchi’s. The same people were designing and building them in the same factory. Only the money, marketing and road-bike styling came from Harley-Davidson. Despite advertising to the contrary, the new road bikes had nothing whatsoever in common with the twin-cylinder, liquid-cooled racing motorcycles beyond where they were designed and built. The racing would bring credibility that should transfer into sales of a range of half cruiser, half dirt-bike, single-cylinder roadsters.

As well as being nervous about the Japanese moving into large-capacity motorcycles, Harley’s shareholders’ recurring nightmare was that their heavyweight V-twins were usually bought by older, more affluent riders who might be retiring in the near future. Having acquired Aermacchi’s skills and the Varese factory, Harley went about cracking the lightweight market with an advertising budget that set magazine editors’ hearts racing. Harley was then owned by American Machine and Foundry (AMF), a huge leisure-industry business whose main income came from bowling alley equipment. They wanted to grow Harley’s customer base and reclaim some of the leisure bike market from the Japanese. If they could open up the European market too, so much the better.

The new engines were two-stroke singles in 125cc, 175cc and 250cc capacities, all available as a road or dirt bike, although in practice the difference amounted to knobbly tyres on different wheels and higher exhausts for the off-roaders. The choice of two-stroke engines seems odd today, but was obvious at the time with only Honda building four-stroke lightweights. The rumour mill had it that, like the racing engines, the power plants were Yamaha clones, but it was not so. All the design work was done in-house by the old Aermacchi crew with an eye on future motocross success. The 250cc cylinder head even had a bolt where a second spark plug could be fitted, and the heavy clutches gave away the racing intentions. ‘Harley-Davidson’ managed a 1978 podium finish in the AMA National Motocross with a 250cc developed in Varese, and the later Cagiva version won a Gold Medal as late as 1981. A double-cradle chassis had no trouble taming some of the lightest bikes in the class.

John Warr, whose grandfather set up the legendary Warr’s motorcycles in the King’s Road, London, remembers the bikes arriving:

It was great. Harleys are a bargain today, but back in the seventies they were really expensive compared to cars, never mind other bikes. The two-strokes were an affordable way for people to get into Harleys, and we sold loads as second bikes to owners of big twins. They were great bikes – certainly part of my riding education, and I’ve still got a few. I’m surprised Harley doesn’t make more of that part of their heritage, especially the racing success.

Mick Walker, the late racer and historian of Italian motorcycles, imported the bikes to the UK and worked hard to save the Italians from themselves:

The first year the bikes sold well. But problems with quality control meant bad publicity and warranty claims which hit sales. The bikes were also about 10–15 per cent more expensive than the competition. And you got the impression AMF weren’t really interested – although Harley had London headquarters, the two-strokes were kept in Whitstable with the bowling alley machines.

Although the road bikes were basic by the standards of most of their competition, things started well in Europe and America. Magazine tests praised the bikes’ combination of Italian handling and American looks, and initial sales were promising. They should have boomed when race fans watched open-mouthed as Harley won their four world championships.

The Harley-Davidson Sprint was produced in Varese exclusively for the US market with an electric start.

Harley/Aermacchi also had a great new rider, Walter Villa, a man Enzo Ferrari called ‘biking’s Nicki Lauda – a thinking racer’. Englishman Chas Mortimer, a faller in Paso’s fatal crash and whose 125 GP record was only recently matched by Bradley Smith, remembers him well:

I’d moved to Italy and lived with Walter and his wife Francesca in the winter of 1969 to 1970. The bike he raced was really an Aermacchi design with the Americans picking up the bills and taking the glory. But some Yamaha partscould be used as spares, andYamaha pistons were found in Pasolini’s bike after his fatal crash.

Two-strokes like this 250cc were intended to replace the expensive to build Aermacchi. Again, all built in the Varese factory that would be bought by Cagiva, who simply rebranded the bikes Cagiva HD.

The brilliant Walter Villa, whose ceaseless testing complimented his and the Aermacchi engineers’ natural talents, brought four world titles to Harley-Davidson. Despite Harley running a huge advertising campaign linking the racer to their small two-stokes the public remained unconvinced. LOTHAR SPURZEM

The frames of the later Harley-Davidson factory racers were by Bimota.

According to Chas there wasn’t much to choose between any of the 250s in those days, and part of Villa’s success was his constant testing because even small differences could give you an advantage. ‘The quick guys came past you on the straights,’ remembers Chas, who finished third in the 350 championship in Villa’s victorious 1976 season, ‘but that was probably because they’d come round the last corner faster than you.’

Villa repaid Harley’s cash with interest, landing the 250 World Championship in 1974, 1975 and 1976, the cherry on that final trophy being a matching 350 crown. 1977 was less kind and, although he still managed third in the 250cc title chase, he was beaten by his new team-mate Franco Uncini and Morbidelli-mounted world champion Mario Lega. Perhaps he was less enamoured with the new Bimota frames (at least they weren’t made by Harley), although the 350 Yamaha on which Johnny Cecotto won his world championship in 1975 had a Bimota frame as well. For 1978, the 250 and 350 classes were a Yamaha benefit, with Villa only able to take the Harley to sixteenth place, jumping ship to Yamaha at the end of the season.

Yet sales of the road bikes that the racing was supposed to generate ebbed away and, in 1978, Harley-Davidson sold the Varese factory to Cagiva and gave up on lightweights and world championship road racing. Today, Harley-Davidson never mention their world championships, probably because they realize it was really achieved by what was Aermacchi in all but name. Business studies’ students must wonder what goes on in Harley’s boardroom because, in a nightmare case of déjà vu, Harley bought the Varese factory back from the Cagiva group in 2008 (by then making MV Agustas) only to sell it back to Cagiva for one euro a year later.

Cagiva did show a proposed road-going version of the Aermacchi/Harley-Davidson 250 twin in 1980, but Yamaha killed it with their own 250LC at half the Varese bike’s projected price. Cagiva instead turned their attention to Ducati.

AESTER (1932–35)

A Turin factory that built 150cc and 500cc four-stroke motorcycles.

AETOS (1913–14)

These were a handful of motorcycles built by the Pozzi company of Turin powered by a 3½ horsepower 492cc V-twin.

AGOSTINI (1991)

A brief run of 50cc two-stroke mopeds using the Franco Morini engine but with no connection to the multiple world champion Giacomo.

AGRATI (1958–65)

Originally a bicycle component manufacturer that expanded into scooter and moped construction. Also sold under the Garelli name between 1960 and 1965. They were also the importers of many Italian motorcycles to the UK during the 1970s.

Garelli were famous for two-strokes long before the sports moped craze. The Ducati is a 450 Desmo ridden by the author on two Motogiro recreations.

AIM (1976–86)

Assemblaggio Italiano Motocicli (Assembling Italian Motorcycles), were based first in Prato, then in Vaiano in Tuscany. At first these off-road motorcycles had 50cc and 125cc Sachs engines. From 1976, mopeds were offered with Franco Morini engines, both with automatic single-speed gearboxes and four-speed manual gearboxes. Eventually, 100cc, 175cc and 250cc models appeared but AIM had to retrench to 50cc and 80cc models, as they fought, unsuccessfully, for survival.

ALATO (1923–25)

131cc motorcycles built by brothers Mario and Giulio Gospio in Turin.

ALCYON ITALIA (1926–28)

In 1910, Cesarani of Caravaggio, east of Milan, started importing French Alcyon motorcycles. Eventually, a 350cc was built under license for the Italian market under the Alcyon Italia banner, initially in Brescia, which had strong connections to both car and motorcycle racing. Production was expanded with a Turin factory from 1925 to include the Alcyonnette 98.

ALDBERT (1951–58)

Small sports motorcycles, including the 175cc Razzo, the Gran Sport 175 and 160cc Turismo Sport and Super Sport models. Based in Milan.

ALFA (1923–26)

125cc and 175cc motorcycles, plus larger capacity models, using JAP engines and Blackburne engines. Based in Udine in north-east Italy.

ALIPRANDI (1925–31)

Milan factory that used various engines, including 175cc and 250cc Moser JAPs. From 1928 there were also 350cc and 500cc models. From 1930 to 1932 they offered motorcycles with 175cc Ladetto, and 246cc and 346cc JAP, engines with overhead valves under the OASA banner.

ALPINE (1944–62)

One of the first moped manufacturers, based in Pavia, and also a supplier to other manufacturers of their 48cc two-stroke engines. This was developed into a record-breaking 75cc motorcycle, and finally into a 125cc.

ALTEA (1938–41)

Originally marketed as Sei, after founder Adalberto Seiling – who had also established Motocicli Alberico Seiling (MAS) in 1922 – and rebranded Altea in 1939. The first motorcycle was a single-cylinder, side-valve 350cc with an external flywheel and unit construction, three-speed gearbox, built in Milan. It was followed by a 297cc side-valve single and an overhead valve 200cc with a cantilever style rear suspension. The same engine was also used to power a small motorboat in 1940 but, due to the war, Altea closed its doors for the last time in 1941.

AMR (1979–85)

Based in Casarza Ligure, east of Genoa, these were 125–350cc motorcycles powered by German Sachs engines.

ANCILLOTTI (1967–85)

Originally a motorcycle repair and tuning business established in Florence in 1907. A Tuscan factory was built in Sambuca Val di Pesa in 1965, with the launch of an off-road range of motorcycles in 1967. Models of 50–450cc were produced, although it was sales of the smaller motorcycles that allowed production to reach up to 3,000 units a year. Powered by bought-in engines by German Sachs, or Italian Franco Morini, Tau and HIRO motors, ultimately they could not compete with the Japanese.

ANCORA (1923–40)

Based in Milan, motorcycles were originally offered in touring and sports versions powered by a two-stroke 147cc British Villiers engine. In 1924, a new model with a 247cc Villiers two-stroke engine was launched, and subsequent offerings, which included a 175cc and a three-speed 350cc, were in essence developments of the earlier models.

ANZANI (1920–24)

The Italian pioneer Alessandro Anzani began to build engines in France, as did his compatriot Ettore Bugatti. Initially, these were for airplanes and motorcycles but, after establishing a factory in Milan, from 1922 he built overhead-valve, 500cc V-twins, alongside a few side-valve 750cc and 1000cc versions.

APE (1923–25)

Established by Ermanno Agostinelli and Luigi Perone in Cirenaica, in the far south-east of Italy, the name is a combination of the first letters of their surnames, but is also Italian for bee. APE used French 98cc Train engines to offer a sport and touring motorcycle. None are thought to survive. They have no connection to the Piaggio APE three-wheelers.

APRILIA (1960–)