28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

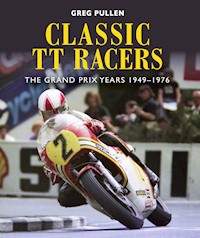

At 10 o'clock on the twenty-eighth of May 1907 the first Isle of Man Tourist Trophy motorcycle road race began. The riders pushed off on their 500cc single cylinder bikes and ten laps and 158 miles later, Charlie Collier aboard a Matchless would be declared the victor. This book is a history and celebration of the bikes of those early years of the TT races. It covers the events and personalities that led to the creation of the race and its challenging course; the early success of the British motorcycle manufacturers: Norton, Velocette, AJS and Matchless and their riders. The origins of the Italian Fours: Gilera and MV Agusta Quattro are covered and the influence and reign of the Japanese manufacturers too are covered: Honda, Yamaha, Kawasaki and Suzuki. There are also details of the technical developments that enabled the bikes to conquer the mountain course with world-record beating times.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

CLASSICTT RACERS

GREG PULLEN

CLASSICTT RACERS

THE GRAND PRIX YEARS 1949–1976

First published in 2019 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2019

www.crowood.com

© Greg Pullen 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 630 2

All images © Greg Pullen unless otherwise stated.

CONTENTS

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 CREATING A LEGEND

CHAPTER 2 BRITISH SINGLE DOMINATION

CHAPTER 3 VELOCETTE KTT

CHAPTER 4 MANX NORTON

CHAPTER 5 AJS PORCUPINE

CHAPTER 6 MATCHLESS G50

CHAPTER 7 THE ORIGINS OF THE ITALIAN FOURS

CHAPTER 8 GILERA QUATTRO

CHAPTER 9 MV AGUSTA QUATTRO

CHAPTER 10 MV AGUSTA TRE CILINDRI

CHAPTER 11 THE JAPANESE ARRIVE BEARING 2-STROKES

CHAPTER 12 HONDA RC181

CHAPTER 13 YAMAHA TZ350

CHAPTER 14 KAWASAKI H1/2R AND KR750

CHAPTER 15 SUZUKI TR/RG500

CHAPTER 16 EPILOGUE

Appendix TT Podium Placings 1949–1976

Index

INTRODUCTION

If you love motorcycles then the Isle of Man will be somewhere you’ve either visited, or plan to go to one day. Consider the long-lost factories of Norton, Velocette, Rudge, BSA, Triumph, AJS and all the rest: the TT is where these British firms built their world domination, and the TT is where Honda went first to steal it away from them.

Indian raced at the TT to prove they could build better motorcycles than Harley-Davidson, and Moto Guzzi taught the world that rear suspension was a good idea on the Isle of Man. The mountain course is where Norton debuted Borrani alloy rims – painted black to fool the competition into thinking they were plain old steel – and where the Gilera and MV Agusta fours were first taken when it was time to test them in competition outside their native Italy. Velocette developed the positive stop foot-change gearbox and Rudge the radial 4-valve head primarily to win at the TT.

For sixty or seventy years the Isle of Man TT races were simply the most important motorcycle races in the world. When a motorcycle road racing championship was proposed in 1948 there was never any doubt that the Isle of Man TT would be a part of it. From the start of the motorcycle World Championships in 1949 the TT classes became must-win races for both riders and factories. Whatever it took to win – money, a better rider, a new technology – it was taken to the Isle of Man. Eventually the mountain course would prove too challenging – read ‘dangerous’ – to remain part of the World Championship and 1976 was the last year in which TT results counted towards the various titles. This is the story of some of the motorcycles that raced in those twenty-eight years, and of a very special mountain course.

Inevitably any research project is as good as those who support it. I am especially indebted to Pat Slinn, who first visited a TT in 1948 – his father was there to develop a new BSA swing arm in the Clubman’s Junior TT. Pat returned as a BSA apprentice in 1958 and has visited the Island’s races every year since. He has worked with Ducati over the course of five World Championships for Mike Hailwood and Tony Rutter. Pat’s introductions to TT legends – he grew up calling Geoff Duke ‘Uncle Geoff’ – have been invaluable. So, too has his friend Bill Snelling who never returned from his first TT: he was so smitten with the racing and the island that he still lives there, the curator of a fabulous photographic archive that can be seen and bought via TTracepics.com.

Thanks must also go to the motorcycle team at Bonham’s. I consult for them, but it is really for my knowledge of Italian motorcycles. Being able to ask Bonham’s specialists about the Velocettes especially was very much appreciated, as are the photographs they have kindly allowed to be included. Finally, and most importantly, thanks to my wife Joanna. A writer’s income is modest in the extreme and the hourly rate best not thought about. Yet Joanna makes sure I have the time and travel needed to complete works such as this, as well as encouragement. Without her and the wonderful stories that are there to be discovered this book would not have been finished. But I have enjoyed it, and hope every reader does as well.

This pretty valley is between two of the fastest parts of the TT course: Sulby Straight and Bungalow. Mike Hailwood once joked that his secret to a fast lap was to use the road through this valley as a short cut.

CHAPTER ONE

CREATING A LEGEND

While the rest of the world seemed happy to accept motorcycle and automobile racing on open roads, Britain was pretty much unique in absolutely prohibiting it. The 1903 Motor Car Act subjected the British to a blanket 20mph (32km/h) speed limit, despite warnings that the embryonic British motor industry was being stifled at birth. Reliability and performance could not be developed while it remained illegal to go faster than 20mph.

The ban became especially humiliating for British motoring enthusiasts when they realized that Selwyn Edge, who won the 1902 Gordon Bennett Cup, would be unable to defend his trophy on home soil as was traditional, and perhaps not at all. But the British Government held firm on the racing ban and speed limit and, with no purpose-built race tracks in existence, options were in short supply.

It’s a near-death thing. Few realize that behind the scoreboard is a cemetery, with Snaefell in the distance.

Almost since the beginning the Island’s Boy Scouts have acted as runners for the scoreboard.

Eventually a compromise was reached with the organizers and competing clubs, who agreed that the ‘British’ Gordon Bennett Cup of 1903 could be held in Athy, a market town in County Kildare in Ireland, some 50 miles (80km) south-west of Dublin. In gratitude to the Irish, the British team painted its car in a shamrock green livery and thus was created ‘British’ racing green.

But British motor sport couldn’t stake its entire future on the generosity of the Irish. So Julian Orde, secretary of the Automobile Car Club of Britain and Ireland, persuaded the Tynwald (the Isle of Man’s proudly independent government) to authorize the island’s first motor race. The Isle of Man is not part of the United Kingdom, although it does enjoy the protection of the British government and, of course, geographically is part of the British Isles. So the High Court of Tynwald – believed to be the oldest continuous parliamentary body in the world – passed the 1904 Manx Highways (Light Locomotive) Act, permitting a 52-mile (84km) ‘Highlands’ Course’ to be used for the 1904 Gordon Bennett Eliminating Trial. This was won by Clifford Earl in a Napier, as was the 1905 trial that was held the following May.

THE FIRST TT

Gordon Bennett became wealthy through journalism and newspaper publishing in New York, although he was of Scottish heritage. Nothing was too outrageous or dangerous for him, his stunts and fabulous motor cars leading to people shouting ‘Gordon Bennett!’ after him, the origin of today’s expression. Unsurprisingly he was soon using his connections and cash to start a fledgling motor car racing fraternity in Europe.

In September 1905 the Royal Automobile Club gladly jumped on Gordon Bennett’s bandwagon with an event dubbed the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy – soon abbreviated to the RAC TT. The island had its first TT, although not for motorcycles. Yet.

With your back to Snaefell there are the pits, a short walk to Douglas Promenade and the Irish Sea.

Having competed in the previous year’s Gordon Bennett Cup, motorcycles were allowed to enter a sister event to the 1905 Gordon Bennett Eliminating Trial. The Manx government was persuaded to allow a motorcycle competition to take place the day after the automobile trial, to qualify riders for the International Motorcycle Cup that was due to be held in Austria in 1906.

The poor hill-climbing abilities of pioneering motorcycles led to the organizers switching the two-wheeled trial from the steep mountain roads of the Highlands Course to a less daunting 25-mile (40km) route. This ran south from Douglas to Castletown and then turned north to Ballacraine, before returning to a start/finish line at Quarterbridge in Douglas. The route included Crosby and Glen Vine, following part of today’s current mountain course, albeit in the opposite direction. This 1905 event was that year’s International Motorcycle Cup, and the five-lap, 125-mile (201km) race was won by J.S. Campbell on an Ariel. He therefore became part of the British team to travel to the following year’s International Motorcycle Cup in Austria.

Unhappily – or perhaps not, given what was to follow – the British riders who arrived in Austria were appalled at what they were found themselves asked to race against, and their collective disappointment would lead to the creation of the Isle of Man motorcycle TT.

Even before it started, the 1906 International Motorcycle Cup was plagued by recriminations. The wicked continentals were, the British claimed, cheating by bolting monstrous engines into flimsy chassis to create pure racing motorcycles that, while within the regulation weight restrictions, bore little resemblance to any production models available to the public.

This made the continentals’ machines uncatchable in a straight line but, the British argued, would send motorcycle development down an – admittedly fast – blind alley. The host nation’s Puch factory was openly using a mechanic riding a sidecar outfit stuffed with spares to shadow its riders. Even the French protested about that, but all complaints fell on deaf ears and were ignored by the sport’s ruling body, the Fédération Internationale des Clubs (FIC). This played a significant part in that organization being replaced by the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme (FIM), motorcycle racing’s primary and overarching governing body to this day.

Lap times are still-hand painted on the scoreboard.

While today’s racing fans might complain that manufacturers wield too much power over race organizers, it was ever thus as the demise of the FIC illustrates. Even in those early days the needs of manufacturers held sway in the real – but then rarefied – world of selling motorcycles. Pioneer manufacturers needed to prove to potential customers that their motorcycles offered robustness, good fuel economy and a modicum of comfort. Flimsy bicycles with heavyweight V-twin engines might win sprint races but they were, to British minds at the time at least, unlikely to promote and popularize motorcycling as an activity rather than as a spectator sport. After all, the industry was likely to sell far more motorcycles if everybody could join in.

So, on the long train journey home from Austria, Freddie Straight, the ambitious secretary of the British motorcycle sport’s governing body, the ACC (Auto Cycle Club), the brothers Henry and Charlie Collier (owners of Matchless motorcycles) and the enthusiastic UK-based aristocrat, the Marquis de Mouzilly St Mars, discussed setting up an alternative to the International Motorcycle Cup.

They ultimately decided upon a race for road-legal motorcycles, based on the RAC TT, to be held on the Isle of Man. The final format was proposed by the editor of The Motor Cycle at the ACC’s annual dinner in London on 17 January 1907. Competitors in the two classes would need to focus on fuel consumption – singles needing to average 90mpg (2.61ltr/100km) and twins 75mpg (3.14ltr/100km) – if they were to complete the course. Fuel would be measured into each entrant’s tank at the start of the race to ensure compliance and, emphasizing the desire to develop touring motorcycles, there were regulations requiring the inclusion of saddles, tools, mudguards and silencers. In practice, riders would also choose to drape spare tyres and inner tubes across their shoulders in anticipation of the inevitable punctures.

The lowland circuit used for the International Cup on the Isle of Man in 1905 had proved gruelling and difficult to manage, so the Auto Cycle Club, hubristically believing the British team would win in Austria, had already plotted out an alternative course for the following year’s event. This, the St John’s Course, was to be adopted for the first TT. The proposed route passed by the old open-air Manx Parliament site in St John’s parish and the race started by the nearby school of that name. – this was fortuitous in that blackboards could be brought outside to record lap times. Across the road was an open field that was literally a paddock – for horses – that was set aside for marshalling and repairs. The name stuck, although these days horsepower rather than real horses is what motor sport fans expect to see in a race meeting’s paddock.

The pits used to be on the other side of the slip road, right on the course; the current arrangement is far safer.

Riding an anti-clockwise course, riders would head north towards Ramsey from Ballacraine to Kirk Michael, following some six miles of the current mountain course. Then they would double back along the coast to Peel, before returning to St John’s. Altogether it was a 15.8-mile (25.4km) route designed to showcase rider and machine capability, rather than bring about a demolition derby.

The St John’s course had roads that were narrower than those of the mountain course, especially the coast road that runs with the Irish Sea on the rider’s right for many miles. Although lacking Snaefell’s climbs, the St John’s course challenged with sharper corners and ran through very few builtup areas. A ten-lap race was envisaged, with a compulsory ten-minute break at half distance. After all, these were the days when a rider was expected to be able to change a broken exhaust valve or ruined tyre and still go on to win a race.

With Britain failing to win the 1906 International Cup, by serendipitous good fortune plans were fully in place to host what the British felt would be an altogether better race. The inaugural international Isle of Man motorcycle races, which had been expected to be the 1907 International Cup, were ready to run as the first motorcycle TT even before it was called that.

And so on 28 May 1907 the TT was born to a cold, grey morning on the Isle of Man. At 10 o’clock the first riders pushed off on their 500cc single-cylinder Triumphs, Frank Hulbert and Jack Marshall riding away to Ballacraine, presumably oblivious of the historical significance of their actions. Ten laps and 158 miles later, Charlie Collier aboard a single-cylinder Matchless would be declared the victor. Averaging 38.2mph, he actually bested the performance of the winner of the 2-cylinder class, Rem Fowler, on a Peugeot-engined Norton. The Isle of Man was on its way to being one of the most famous destinations for motorcycle enthusiasts on earth, something that is perhaps more true today than it was in those pioneering days.

THE MOST BEAUTIFUL RACE COURSE ON EARTH?

Yet the first thing that must surely strike visitors to the Isle of Man, especially during the forty-eight weeks of the year when motorcycling largely abandons the island, is the breathtaking scenery. Sweeping, sandy beaches are sheltered by sheer rock faces that fall away inland, yielding up wooded springs and friendly paddling streams. Narrow lanes squeeze between fuchsia hedges and ancient stone walls as if they were tendrils of some long dead mycelium. Feral chickens ambush picnickers, making the most of the absence of foxes on this rock between Ireland and Great Britain. Then there is the mountain, Snaefell (Norse for ‘snow mountain’), which can be brooding in swathes of mist or majestically beautiful, particularly in late summer and autumn as the heather drapes the towering landscape in a purple cape. All the while the sheep stare benignly at visitors to one of the most beautiful and eerily peaceful places on earth.

Go there other than during the Southern 100, TT, Classic TT and Manx Grand Prix, and you might never realize the island has a great motorcycling heritage. Mona’s Isle might be home to one of the most important, oldest and historic motorcycle racing courses on earth yet, in 2007 when its residents were invited to take part in celebrations marking the centenary of the first-ever motorcycle TT, many of the indigenous population didn’t fully realize its international significance.

As with the Spa Francorchamps circuit in Belgium, no amount of time spent viewing on-board racing footage prepares you for experiencing the climbs and descents of the Isle of Man’s mountain course at first hand. Even more shocking is that when a rider warns that a corner is blind, they don’t just mean a late apex – they mean you ride with an open throttle alongside solid stonework, trusting absolutely that your recollection of what comes next isn’t fatally flawed. Then, as you climb up into the clouds, it can feel as if you’re about to launch skyward before you snap left – and there’s the road again, cut into the green and black of Snaefell.

This is a Monza-esque, full-throttle red line of tarmac across a mountainside that offers nothing but a steep and unforgiving drop punctuated by dry stone walling and rocky cuttings. But, unlike Monza, the TT course wasn’t built for racing, but rather is a circular route of public roads co-opted to prove the worth of motorcycles and their riders. This is what makes it a course, rather than a circuit: the latter is a fixed and permanent racing venue, which means that you can ride a circuit of the course or just use it as part of the public highway. The pedantry of the English language!

Winner of the twin-cylinder class of the first TT, Rem Fowler.IOMTT.COM

Rem Fowler’s motorcycle was a Peugeot-engined Norton.

The highest point of the course, near Brandywell, is some 422m (1,385ft) above sea level, lying in the shadow of Snaefell’s 621m (2,037ft) summit which, in the clearest weather, allows you to plainly see five kingdoms: England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Heaven. It adds a dramatic dimension to the Island’s emerald splendour.

But eventually you are brought back to earth, remembering Conor Cummins’ crash up here in 2010. The top men aim 200bhp and nearly 200mph of rider and motorcycle between the faulted and folded sedimentary rocks, between houses and telegraph poles. Danger and exhilaration or, as Bianchi and Alfa Romeo racing legend Tazio Nuvolari put it, ‘women and engines; joy and pain’.

Why do they do it? Because they love the challenge of the last traditional motor sport event on earth. Yet, although safety has improved beyond all recognition, the 4-cylinder bikes that largely rule the TT are now so quick that it seems the Senior TT is unlikely to ever run in rain again. So the TT remains undoubtedly the most dangerous sporting arena in the world, although Sammy Miller puts it more bluntly. The Irishman was a road racer of note at the TT, riding for Mondial and Ducati in the 1950s, before becoming famous as a trials maestro. This is what he has to say about the TT in the twenty-first century: ‘Madness. 200mph through there? You’ve got no chance.’ Yet reminded there were more fatalities in the sport when he was active in road racing, his thoughts on his fellow competitors are even more sobering. ‘We could be losing one a week. Sometimes I don’t think you need to think too much as a racer. You don’t want to be flying along thinking “What if the gearbox gave up now?”’

It’s odd to think how little human life was valued in the early years of the twentieth century. In the USA, board-track racing spectators would pay to be photographed next to dead riders and their machines, left where they fell to boost income for race organizers. Helmets were only thought of after T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) was killed on his Brough Superior, causing a young Hugh Cairns, one of Britain’s first neurosurgeons, to start research on the head trauma suffered by motorcyclists when they crashed. A single-cylinder motorcycle with a handful of horsepower might seem unimpressive today, but was quite capable of killing a pioneering motorcycle racer. Even by the late 1960s the mountain course was unquestionably the most dangerous race track on earth. Horrendously tricky to learn, and brutally unforgiving of even minor errors, it is easy to understand why even the most fanatical motorcycle enthusiast might consider the TT a distasteful and unwelcome reminder of a bygone age: a time when human life was seen as a tradable and disposable commodity.

A rider might achieve greatness on the Isle of Man, but he stood a higher chance of being killed there than at any other sporting event in the world, a fact that remains unequivocally true today. The very nature of racing on closed roads racks up the odds of something going catastrophically wrong: machinery fails; conditions are unpredictable; stone walls are immovable. Inevitably, people die. Racing along public roads, flashing between buildings, speeding up and over a mountain before charging down to a rocky coast has never been less than hazardous, and motorcycle racers think only of glory and self-satisfaction in achievement, never believing it will be them who one day – perhaps even today – has to pay the ultimate price.

Guthrie’s Memorial on Snaefell, the mountain section of the course.

FREEDOM OF CHOICE – BUT SOMETIMES NOT

A rider chooses to submit himself (and occasionally herself) to the challenges of racing on the Isle of Man. But for a brief period many were given no choice. When the world motorcycling championships were first run in 1949, only two of the six rounds were held on purpose-built circuits, as opposed to courses that included closed public roads. These circuits were Monza in Italy and Bremgarten in Switzerland, but the latter banned most motor sport altogether after the 1955 disaster at Le Mans, when a car crashed into the crowds killing over eighty people.

But gradually the co-opted courses shrank to became permanent circuits and much safer, while the Isle of Man remained, well, the Isle of Man. Yet as a round of the World Championship riders – especially if employed by a team or factory – were often obliged to race there. Inevitably, eventually one star too many was killed, Morbidelli’s Italian rider Gilberto Parlotti, and the top riders sensed a change of mood. Parlotti had been a good friend of MV Agusta’s superstar rider Giacomo Agostini, who led the revolt. His masters, also Italian, took his wishes to heart and, given that at the time riders could drop their poorest results from the season’s final tally, it was less likely to affect World Championship standings than it would now.

Initially the sport’s governing bodies, the international FIM and its British equivalent, the Autocycle Union (ACU), felt the stars would drift back or that factories would force riders’ hands. It didn’t happen and when the sports’ newest and greatest superstar, Barry Sheene, made it plain that he would never return to the TT, the powers that be realized they were on the losing side. 1976 was the final year that the Isle of Man hosted a World Championship Grand Prix, Silverstone on the mainland being awarded the prize of hosting the British Grand Prix. Most thought that would bring an end to the TT races, but the return of Mike Hailwood in 1978 and 1979 reinvented the event. Ironically it now thrives, and has made stars of its greatest riders. Guy Martin is probably as well known as Valentino Rossi, and John McGuinness’s and Michael Dunlop’s names trip off motorcycle enthusiasts’ tongues as readily as do those of most MotoGP stars.

Why does the TT still thrive? I would suggest that what the TT and Classic TT offer is access. At a MotoGP event the spectator experience has been diluted beyond recognition, ostensibly in the name of safety but, older fans suspect, in the pursuit of profit and especially television coverage. When my generation started going to races in the mid 1970s there was a good chance of bumping into Barry Sheene, Kenny Roberts, Phil Read and Giacomo Agostini. That is unthinkable now, yet at the TT not only is there a fair chance of bumping into John McGuiness, there is also a fair chance he and wife Becky will stop and chat to you. And then when he’s racing you can pick a viewing spot a few feet from the course and feel the rush of air as he passes.

Museum and guardian up by Bungalow.

Almost at the highest point of the course riders enjoy the privilege of riding in the tyre tracks of heroes.

The Joey Dunlop memorial up above the Bungalow section of the course.

You can also have little idea of what it is like to ride a MotoGP circuit on a MotoGP bike unless you have very deep pockets. But the TT course is always there, and on Mad Sunday the mountain section is one way only and speed limit free. Since the racers use motorcycles based on those in showrooms – albeit sometimes expensively modified but still closely related to what you can buy – you can get to know how deep a TT racer’s talent goes, and briefly understand why they do it.

But why does the Isle of Man government do it? The TT is horrifically expensive to run: prize money alone is around £250,000, never mind the appearance fees and cost of actually running a race that involves preparing public roads for 200mph motorcycles. The answer is in the Great British holiday: like the equivalent United Kingdom coastal resorts the Isle of Man used to benefit hugely from tourism, a business now largely lost to Jumbo Jets and the sunny climes of southern Europe. But the Isle of Man has the TT races and today well over 40,000 people come to see them, some for a full fortnight. They pay for hotels, bed and breakfast, meals out and much more: the Isle of Man’s autonomous status means that its government keeps all of the tax revenue so generated, which explains the TT’s survival.

The chapters that follow are a history and tribute to some of the most important and successful motorcycles that raced during the TT’s years as host of the British round of the motorcycle World Championship. The selection criteria were that the motorcycle must have at least secured a podium finish in the Senior (500cc) TT, then the Blue Riband class of the World Championship. A motorcycle that won a Senior TT during that era gets included automatically. Dominance in the only other race always run at the TT – the 350cc Junior – is also a reason for inclusion. Happily this gives a more-or-less chronological order that illustrates early dominance by British singles, the success of the Italian multis and the eventual rise of the 2-strokes and Japanese factories.

CHAPTER TWO

BRITISH SINGLE DOMINATION

It is hard to believe that shortly before its collapse in the 1970s BSA was building more motorcycles than any other factory in the world. Today all that is left of BSA’s Birmingham factory is car repair workshops and such, plus a small building that has a BSA sign outside and still makes small arms, the origins of the name BSA (Birmingham Small Arms). There is nothing else to mark out one of the glories and stupidities that were shared between the British (in truth English) motorcycle industries.

BSA took its world dominance for granted, and the people who made the money had no interest in motorcycles or even in engineering. After a sales manager took lunch in the BSA’s directors’ dining room he was taken to one side and told he should never again bring riding attire into such hallowed quarters. BSA chairman Sir Bernard Docker allowed his wife to order a Daimler (then – how the mighty fell – a subsidiary of BSA) with gold plating, ivory fittings and zebra-skin upholstery. This sort of behaviour was often funded by tax writeoffs or simply designated as necessary company expenditure, ultimately costing Sir Bernard his position. It seems unlikely, however, that he and his fellow leaders of industry suffered from the collapse of the British motorcycle industry as much as those who actually built the motorcycles, owned dealerships or otherwise relied on Britain’s world-beating factories. And of course everybody suffered when government found its tax revenues in freefall.

How this hubris came to pass is not difficult to see. France and Belgium had led the way in the early days of automotive design and manufacture, but the two world wars destroyed their early lead. Italy and Germany then took up the baton, but again war left them in ruins. The British had an open goal and even dismissed lightweights from Japan and Italy as mere fodder for those just starting out, expecting riders to eventually graduate to a large-capacity British motorcycle. How wrong they were.

Despite building grand prix twins, Triumph achieved little at the TT during its years as the British Grand Prix.