28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

BSA was once the world's most successful motorcycle company, manufacturing more machines than any other in the world by the mid-1950s. And yet, after winning the Queens Award to Industry for exports in 1967 and 1968, it collapsed into bankruptcy in 1973. This is an epic story of rise and fall, even by the precarious standards of the British motorcycle industry. With over 170 illustrations, this book recalls the founding of the company and its foray into bicycle and then motorcycle production. It describes the evolution of the various models of motorcycles including specification tables and discusses the diversification into cars, commercial vehicles and guns for Spitfires. It recounts the successes - two Maudes Trophies and numerous racing victories, and documents the fall from grace to bankruptcy and beyond.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 320

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

BSA

THE COMPLETE STORY

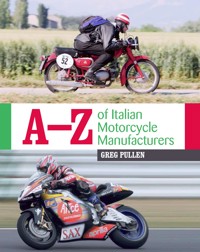

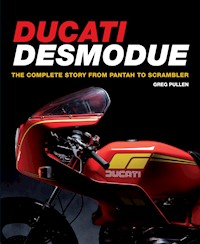

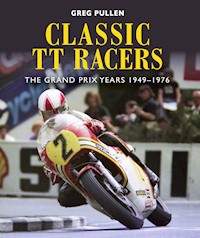

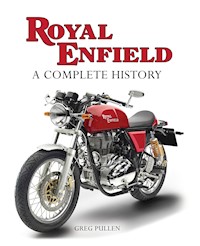

OTHER TITLES IN THE CROWOOD MOTOCLASSICS SERIES

AJS AND MATCHLESS Matthew ValeBMW AIRHEAD TWINS Phil WestBMW GS Phil WestDOUGLAS Mick WalkerDUCATI DESMODUE Greg PullenFRANCIS-BARNETT Arthur GentGREEVES Colin SparrowHINCKLEY TRIUMPHS David ClarkeHONDA V4 Greg PullenMOTO GUZZI Greg PullenNORTON COMMANDO Matthew ValeROYAL ENFIELD Mick WalkerROYAL ENFIELD BULLET Peter HenshawRUDGE-WHITWORTH Bryan ReynoldsTRIUMPH 650 AND 750 TWINS Matthew ValeTRIUMPH PRE-UNIT TWINS Matthew ValeVELOCETTE PRODUCTION MOTORCYCLES Mick WalkerVELOCETTE – THE RACING STORY Mick WalkerVINCENT David WrightYAMAHA ROAD-RACING TWO-STROKES Colin MacKellerBSA

THE COMPLETE STORY

GREG PULLEN

First published in 2020 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2020

© Greg Pullen 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 740 8

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

BEGINNINGS

CHAPTER 2

TROPHY CHASING – AND A THING FOR CARS

CHAPTER 3

A RETURN TO MOTORCYCLES

CHAPTER 4

A WORLD AT WAR

CHAPTER 5

EXPORT OR DIE – THE BIG TWINS

CHAPTER 6

RESTARTING THE SINGLES

CHAPTER 7

THE POLITICS OF GROWTH – AND SEEDS OF FAILURE

CHAPTER 8

THE BANTAM

CHAPTER 9

SCRAMBLING TO WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS

CHAPTER 10

PART OF THE UNION I: MODERNIZING THE SINGLES

CHAPTER 11

PART OF THE UNION II: MODERNIZING THE TWINS

CHAPTER 12

A DANCE IN TRIPLE TIME

CHAPTER 13

FIDDLING WHILE ROME BURNS

Appendix: BSA Production Models Year by YearIndex

DEDICATION

To Pat Slinn, for a life devoted to BSA and Ducati motorcycles.

Rocket 3 engine in a replica Rob North frame in Parc Fermé at the Manx Grand Prix/Classic TT.

Detail of an A65-based Norbsa – a Norton Featherbed frame with BSA power.

INTRODUCTION

BSA – or ‘The BSA’ as those who worked there referred to it – was once the world’s most successful motorcycle factory, making more machines than any other in the world by the mid-1950s and employing some 20,000 people. The factory won the ‘Queen’s Award to Industry’ for exports in 1967 and 1968, before collapsing into bankruptcy in 1973. It is an epic rise and fall story, even by the standards of the British motorcycle industry.

A warehouse on the far side of the canal, similar to and close to the BSA buildings.

My first motorcycle was a BSA, a faded green 249cc C15 registered the day I was born way back in the summer of 1959. My father was convinced we would end our lives together as well, horrified that I’d spent £60 of my own money on a motorcycle with a claimed 70mph performance, rather than step from my Puch M2 moped into the Austin A35 car he’d wanted me to learn to drive in. Of course I was happy to do that when friends with a full car licence needed a lift on a Saturday nights, but I wouldn’t pass my car test until three years later, long after I gained a full motorcycle licence and a Suzuki GSX1100. After all, we’d studied George Orwell’s Animal Farm at school and I was convinced the pigs had got it completely wrong: it was two wheels good, four wheels bad.

1959 C15 in rather better condition than the author’s first motorcycle.ARRIVISTO GREEN

But a seventeen-year-old’s sympathies tested the C15 to near destruction. All my motorcycle-mad friends had left school at sixteen and fallen into the arms of the Japanese importers and hire purchase. I stayed on for A levels, so had to take what I could on the (very, very) second-hand market. In isolation I loved the C15, but it wouldn’t start if it was hot, and the ammeter was lost to a hedgerow as I overtook the school bus one afternoon. And there was no way it could keep up with my friends’ oriental quarter-litre lovelies. The C15 went to a pair of lads, who pushed it up and down our street while my younger brothers giggled hysterically. Eventually the lads started it and I had cash in my pocket that would in due course help fund a Honda CB125S.

Then I went on to study business, the course based around the débâcle of a British motorcycle industry run by people who didn’t like motorcycles and understood them even less. I became part of a generation that ridiculed their elders’ ancient British steeds and embraced everything that BSA’s directors didn’t think their customers might want: push-button starting, professional dealerships, indicator lights, and the complete reinvention of the wheel at every opportunity.

And yet… as someone who fell in love with Italian motorcycles in general, and Ducatis in particular, I came to reappreciate the charms of a motorcycle with heritage, and also with that indefinable trait, character. One man singlehandedly changed my attitude towards British motorcycles, a man who rose from a plastering apprenticeship to owning a sizeable property empire. John Bloor turned the British motorcycle’s last stand at Meriden into a housing estate before plotting Triumph’s return. He understood that the revived marque didn’t need to be cutting edge but had to be utterly reliable, and have an authenticity that spoke to motorcyclists jaded by Japanese efficacy. His newly commissioned 3-cylinder motor especially was a peach, and the early Speed Triple a star. Bloor even bought himself one of the originals, an X75 Hurricane that was developed by BSA and would have been sold under that banner if history had played out differently.

BSA’s first step into life was not a great omen. In June 1861, at a meeting in a Birmingham hotel room, the decision was made to form a public company, The Birmingham Small Arms Company Limited, to manufacture guns. Unfortunately within a few years the market for firearms collapsed, and by 1876 the company faced ruin. It was only a chance encounter with a German immigrant that moved BSA into bicycle production, and ultimately motorcycles. This was initially via building bicycles that could be fitted with imported engines, finally showing an in-house designed and built 498cc side-valve single, listed as the BSA 3.5HP at the 1910 Olympia show. The model sold out for each of the following three years. Within a decade V-twins were added to the range and BSA started to diversify: cars, commercial vehicles, Browning .303s for Spitfires – BSA seemed to rise effortlessly to that number one position.

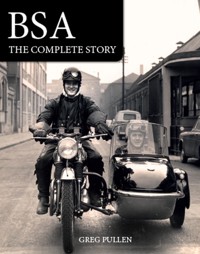

Pat Slinn on his way to Vienna and an international BSA meeting. Passenger Reg Read used to be an Ariel display rider.COLLECTION OF PAT SLINN

Pat Slinn with his homebrewed ISDT bike for a Classic Bike magazine photoshoot.

Although Honda had overtaken BSA as the world’s biggest bike builder as the Swinging Sixties dawned, BSA were far from beaten. Contrary to widespread belief ‘The BSA’ continued to invest in factories and development, with their finest machines appearing during this period, including the Gold Star and the Rocket III. The latter begat the Hurricane, stolen by Triumph management and today the most valuable of the production BSA/Triumph models.

It was this internal rivalry and associated ill-judged government policy that killed BSA, as it eventually did the rest of the British motorcycle industry. Taxing domestic enterprise at every opportunity while allowing unrestricted imports discouraged investment at home, while it was encouraged in Japan’s protected home market. Hubris – a word to be used a lot – meant that neither the British government nor industry saw imports as a threat. Eventually this led to racing victories in the all-important US market being achieved with empty showrooms, bodges to speed up deliveries, and a reputation for disastrous reliability. Panic-stricken directors finally realized they didn’t have a grasp of what motorcyclists wanted, and brought in outsiders who knew even less. A glorious slice of British history and industry imploded, leaving the most deserving – the factory workers, suppliers, dealers and motorcyclists – hugely impoverished.

BSA Motorcycles – The Complete Story tells the story of this astounding rise and fall. As well as what became of the factory – it still sits forlorn and unacknowledged at the side of a Birmingham canal –there will be insight from those who worked at the factory, and those who oversaw the Japanese takeover of the industry. The highs – two Maudes Trophies, racing victories, those Queen’s awards – will be contrasted with the rapid fall from grace. There will be references to the non-motorcycling production – which included Daimler cars – and a possible future in the ownership of Mahindra, which has hinted at a new range of BSA motorcycles after paying three million pounds for the rights to build them.

In writing this history I owe a very special thanks to three people in particular: world sidecar champion Stan Dibben, who worked at the factory building Gold Stars from 1949 to 1952, and competed and tested for BSA. To Chris Smith, daughter of Jeff, for her insights and introduction to her father; his book, Jeff Smith: Trials Master, Motocross Maestro is essential reading. But most of all thanks must go Pat Slinn, a man most famous for his connections to racing Ducatis during the 1970s and 1980s. But Pat started as an apprentice at BSA, and worked in the experimental department as his father had before him. To say he had an insight into the factory is a massive understatement, and without him I could never have written this book.

Gratitude is also due to Gerald Davison, a man who raced a Greeves and then a Honda, before working for Honda, ultimately at director level. Finally a huge thanks to Bonhams for allowing the use of some of the many photographs of motorcycles they have sold.

CHAPTER ONE

BEGINNINGS

There was only one place I could start this story, and try to understand the feelings of those involved in BSA’s heyday: Birmingham’s Bullring is now a huge temple to those who prefer to worship in a shopping centre, but it was once where Birmingham’s motorcyclists congregated. The name comes from the iron hoop to which a bull’s nose ring was joined by a length of rope, ready for the auctioneers’ gavel. I feel a measure of trepidation when asking about the factory’s whereabouts at the Bullring’s taxi rank, but needn’t have – the driver knows exactly the location of what is left of the BSA factory. Almost £10 later I’m standing in front of what was once the biggest motorcycle factory on earth, a surprising stillness around me after the traffic jams of the journey here.

Armoury Road in 2017.

All roads lead to Birmingham.SIMISI1

The buildings are still easily recognized, if unloved. One is a car workshop, rammed with discarded bumper panels. At the far end a single-storey building, in red brick like the other original edifices, has bright, polished letters along one side set into blinded windows – BSA: Birmingham Small Arms, advertised as the ‘long-established air-rifle manufacturer and retailer, also selling scopes, pellets and silencers’. This is all that’s left of a proud history that gave the Armoury Road I’m standing in its name. No blue plaque, no tourist information board, nothing. The canal that runs from the end of the road has recently been refurbished in a multi-million pound investment that failed to find a few pounds to remember what was perhaps Birmingham’s finest hour.

Overlooking the canal is another sad and unloved building, gradually decaying, a metaphor for the decline of British industry through the 1960s and 1970s. A sense of entitlement grasped a nation that had been the world leader in innovation, enterprise, and the belief that to be born British was the greatest gift any child could wish for. On the other side of the world the Japanese embraced the post-war possibilities, while Britain – bankrupt and stripped of empire by World War II – was bereft of ambition. Those in the boardroom felt they could return to their unquestioned old world authority, while others, who had seen those men fight, decided it should be the working man who held the levers of power.

‘People would come into work with their fishing rods, expecting a walk-out,’ remembers Pat Slinn, who, like his father, worked in the experimental department. ‘I’d ride my Bantam in round the back to avoid the pickets, but most people just fancied a day off.’ Perhaps they should have been more careful of what they wished for. I walk back to the city centre along the beautifully restored – but completely deserted – Grand Union Canal, the smart gravel towpath pleasingly litter free.

Back in the hotel room I email a photo to Chris Smith, daughter of BSA’s world champion Jeff. The family lives in Wisconsin close to the great lakes, running Motorsport Publications which distributes UK magazines and books to US readers. Chris and Jeff are unequivocal: they never want to see the factory again – it would be just too heart-breaking. I’d met Pat Slinn earlier in the nearby National Motorcycle Museum. After falling silent in the middle of the first hall he stops and raises his hands in the air: ‘What happened to it? Where did it all go?’ he asks. This is an attempt to find out.

These innovative part-reinforced concrete BSA buildings were some of the first of their type in the world. Sadly today they are unloved and used for car repairs.

IN THE BEGINNING

Birmingham (originally Bermingehame) means the home of the Beorma, some long-forgotten Anglo-Saxons. By the early twelfth century it had grown into a town, and in 1166, King Henry II gave the Lord of the Manor, Peter De Birmingham, the right to hold a market, which was soon drawing merchants and craftsmen to the area. By the late fourteenth century Birmingham was known for its metalworking, helped by the proximity of iron ore, coal and surrounding streams turning watermills that powered the bellows of the many forges.

In 1570 a writer observed that Birmingham was ‘full of inhabitants and echoing with forges’, the metalworking industry fast taking over the area. Tudor Birmingham gained a reputation as a place where cutlers made knives, nailers made nails, and blacksmiths worked at their forges. Inevitably this work included making swords and, in turn, an evolution to gunpowder weapons. But each tradesman tended to work alone, and even by the time rifles were being made, there would be specialists for barrels, stocks or even trigger guards. Mass production it was not, and a few men with foresight realized that there needed to be a coming together of like-minded – but variously skilled – smiths.

The Birmingham Small Arms Trade Association gave the city’s master gunsmiths a chance to join forces in 1854, with John Dent Goodman elected as chairman the following year. This was a group of men (perhaps as few as fourteen, perhaps as many as twenty-four) intending to supply munitions (particularly handmade muzzle-loading rifles) for the Crimean War.

Presumably the union was successful because, meeting together on the Friday evening of 7 June 1861, the association decided to form a public company, the Birmingham Small Arms Company Limited, in the Gun Quarter of England’s second city, with Goodman remaining chairman. The War Office promised the BSA gunsmiths free access to technical drawings and to the War Office’s Board of Ordnance’s Royal Small Arms factory at Enfield – as in Royal Enfield. New machinery developed in the United States (US) had been installed at Enfield, and greatly increased output without needing more skilled craftsmen.

The great and the good of Birmingham viewed the expansion of Enfield with suspicion, knowing that the dedicated factory’s proximity to London and its long history of producing firearms gave it an advantage over the loose-knit gunsmiths of Birmingham. Throughout the evolution of the British rifle the name ‘Enfield’ is prevalent, meaning the Royal Small Arms Factory in the town – now suburb – of Enfield – hence its eventual renaming as ‘Royal Enfield’. This factory, north of London, was where the British government had produced muskets since 1804.

Birmingham’s canals are used for leisure today, but were essential to the city’s prosperity.WONJONG OH

The first British repeating rifle was developed in 1879, and adopted as the Magazine Rifle Mark I in 1888, commonly referred to as the Lee-Metford. ‘Lee’ was James Paris Lee, a Scottish-born Canadian-American inventor who designed an easy-to-operate turn bolt and magazine to work with it. ‘Metford’ was William Ellis Metford, an Englishman instrumental in perfecting the smaller .303 calibre – the calibre of the Spitfire’s Brownings. These developments led to the Lee-Enfield repeating rifle, which served as the British Empire and Commonwealth’s main firearm during the first half of the twentieth century. It was also the British Army’s standard rifle from its adoption in 1895 until 1957, so if Birmingham couldn’t persuade the government to allow them to be part of the project, its firearms industry was doomed.

Lee-Metford Mk II .303.ARMÉMUSEUM / SWEDISH ARMY MUSEUM

The BSA’s stated purpose on establishment in 1861 was to make guns by machinery and, although no mention is made of it, the only significant conflict by this time was the American Civil War, the Crimean War having ended in 1856. This would prove the fallibility of building a city’s future around weaponry: there are times in history when wars are thankfully rare, and they are often unpredictable. BSA, like Royal Enfield, would have to find an alternative revenue stream, and they would both fall upon the same idea: the motorcycle.

BSA settled on a 25-acre (10-hectare) site at Small Heath on the condition that the Great Western Railway would build a station nearby. By 1863 the factory was complete, standing alone in open countryside, a square, red-brick fortress with towers at each corner, apparently mainly employing women, judging by photographs of the era. It was set south of the Coventry road and what is now the A45, to the south-west of the city centre and squeezed between the new Small Heath train station and one of the final sections of the Grand Union Canal, which absorbed the older Warwick and Birmingham Junction Canal. This ensured swift loading and excellent links to Manchester and London, as well as to the ports of Liverpool and Bristol.

When you visit Birmingham it’s never long before a proud local will tell you that ‘Birmingham has more miles of canal than Venice’. Is this true? The exact numbers depend on where you draw the city boundaries, but the system adds up to around 100 miles (160km) of canals. It was certainly one of the most intricate canal networks in the world, the life-blood of Victorian Birmingham and the Black Country. At their height, the canals were so busy that gas lighting was installed beside the locks to permit round-the-clock operation. Boats were built without cabins for maximum carrying capacity, and a near-tidal effect arose from swarms of narrowboats converging on the Black Country collieries at the same time each day.

In 1866 BSA acquired a munitions factory in Adderley Park, about two miles (3km) north of the Small Heath site and again between a train station and a waterway, this time the Birmingham and Warwick Junction Canal, which connected to the Warwick and Birmingham Junction Canal. This allowed BSA to fulfil a government order to upgrade 100,000 muzzleloading Enfield rifles. In 1873 the Adderley Park Rolling Mills became home to the Birmingham Small Arms and Metal Company, to fulfil an order from the Prussian army. Following the government’s switch to the Martini-Henry rifle in 1871, BSA followed suit, producing these from 1874.

Unfortunately the demand for firearms collapsed as peace became established around the world, leaving the founding fathers of BSA’s business plan in tatters. By 1876 they faced ruin, and on 19 August 1878, the factory closed and remained shut for a year until a small order for guns encouraged the managers to reopen. They also sought diversification, realizing that being entirely reliant on one product – firearms – was foolhardy. This attitude of seeking out new products and markets would come to define BSA, ironically until a focus on two very particular motorcycles precipitated its demise.

THE FIRST TWO-WHEELED BSAS

Happily, in 1880 a slightly odd visitor came to the factory, one Edward Carl Fredrich Otto, who had built a novel type of bicycle with a large wheel on each side of the rider, rather than in front of and behind the saddle. He had been introduced by Messrs Smith and Lamb of Ipswich, with a request to manufacture his Otto Patent Safety Dicycle (rather than bicycle). BSA’s directors allowed Otto to demonstrate the ‘dicycle’ by lifting it on to the boardroom table and riding back and forth, while he explained how to balance the machine and the oddball steering. He completed his party piece by riding down the staircase and into the street.

Advertisement for the Otto Dicycle.

It was a historic moment, and the directors were convinced that the future of BSA lay with the production of road transport. They agreed to manufacture the Otto dicycle, and on 2 July 1880, a contract was agreed for BSA to build 210 at £8 15s each, less tyres, the first being delivered on 20 September. Despite this first contract resulting in a loss, a second contract was agreed to supply 200 Ottos at £13 each, with tyres. In all, a total of 953 machines were built and sold by the Otto Bicycle Company of 118 Newgate Street, London, at £21 apiece.

So having diversified into bicycle building, BSA introduced its own design the following year before adding tricycles to the range. These were branded with badges carrying the three crossed guns, which, although it had been used within BSA for some time, only became officially registered in 1881. This ‘piled rifle’ trademark was to become a familiar sight throughout the world, an instant explanation of a huge motorcycle factory’s origin.

Unknown sampler of an Otto Dicycle circa 1882.

In August 1885 – the year Bianchi was founded, still famous for its bicycles – BSA was awarded a bronze medal for their safety bicycle at the International Inventions Exhibition, and BSA’s production of so-called safety (that is, easy to stay aboard compared to the Penny Farthing) bicycles, and tricycles, steadily increased. But in 1887, the government – more specifically the British Empire’s – demand for rifles and ammunition was such that the company abandoned bicycle and tricycle manufacture. The people at the top of BSA were gunsmiths and, to free factory floor space to build more Lee-Metford rifles, between 1888 and 1893 BSA returned to its roots, turning production over entirely to the magazine rifle. But within five years, the market for armaments collapsed once again and a return to bicycles was contemplated.

Bicycle sales had skyrocketed while BSA had been away, thanks to the invention in 1887 of the pneumatic tyre. John Dunlop was a Scottish vet working with his brother James in Downpatrick, south of Belfast, who first made pneumatic tyres for his child’s tricycle before developing them for bicycle racing. He sold his rights for a modest sum, unaware how pivotal his invention would be, his only reward being a sort of immortality as his name remained when the Dunlop Rubber Company was established in Birmingham in 1901.

BACK TO BICYCLES

By a stroke of good fortune a Mr George – apparently known as Billy – Illston called at the BSA factory to see his friend Mr Clements about a billiards match, and noticed that some of the shell-making plant was idle. He urged his friend, and anyone else at BSA who would listen to him, to use the redundant machinery to make bicycle parts. In return he would become the company’s first commercial traveller, living solely on the commission he earned. So early in 1893, BSA started to make bicycle hubs, examples of which were exhibited at the Crystal Palace Show later in the year.

By November 1893 Illston was working full time for BSA, selling hubs and other components across the country. The trade price of hubs was 15s (shillings) (75p) per pair in dozen lots; Brown Brothers of London contracted for 2,000 pairs. Success came quickly. People used to the precision of gun making did not relax their standards when they turned to other work, and the BSA hubs were soon joined by bottom brackets, chain wheels and other parts, which were soon acknowledged as the finest available. It was these components that built BSA’s early reputation for quality.

As the cycling boom continued, more buildings sprouted up at the Small Heath site, soon doubling the factory’s floor space. In the first decade of the twentieth century the expansion continued, BSA now very much a bicycle maker in the public’s imagination.

Then in 1902, Triumph launched their first motorcycle, expanding rapidly from bicycle production with funding from Dunlop tyres. The vehicle was an immediate hit, powered by a single-cylinder four-stroke Belgian Minerva engine with automatic inlet valve and battery/coil ignition, clipped to the downtube of a Triumph bicycle frame.

Minerva had started out manufacturing bicycles in 1897, before expanding into light cars and motorized bicycles in 1900. It might be hard to believe now, but Belgium was at the forefront of the internal combustion engine’s development, its head start destroyed by World War I. The company took its name from the Roman goddess of wisdom and strategy, and as the sponsor of arts and – most importantly – trade. They produced lightweight clip-on engines that were mounted below the bicycle front down tube, specifically for Minerva bicycles, but also available in kit form suitable for almost any bicycle. The engine drove a belt that turned a large gear wheel attached to the side of the rear wheel opposite to the chain. In 1901 the kit engine was a 211cc unit allowing comfortable cruising at around 20mph (30km/h), and half as much again on full throttle.

1904 Minerva-powered BSA in the National Motorcycle Museum.

In these pioneering days the horsepower rating was not as universal as it is today, where the quoted brake horsepower (bhp) is a measure of an engine’s ability to turn a brake of some sort. While this empirical measurement was available to engineers from the birth of the internal combustion engine, British tax authorities at least insisted on a theoretical calculation based upon the engine’s specification, determined by the RAC in the UK. This equated one horsepower equal to 2sq in (12.9sq cm) of piston area, and came to be known as the Treasury Rating. Perhaps even more oddly, manufacturers would list models by this rating rather than give them a name: it was the 1930s before this really changed, and even the fabulous Coventry Eagle Flying Eight was thus named after its RAC 8 HP rating, despite producing around 30bhp.

Thus while Minerva claimed 1.5bhp at 1,500rpm, the motor was rated at 2.25HP in the UK. These kits to turn bicycles into powered two-wheelers were exported as far as Australia. Minerva struggled to build on their early success, hampered – hammered even – by two world wars and the Depression, but were still making Land Rovers under licence for the Belgium army as late as 1956.

Triumph sold 500 of their Minerva-powered motorcycles in 1903, and started prototyping with British JAP (John Alfred Prestwich) motors for an expanded range. The same year BSA experimented with a motorcycle with a BSA pattern frame fitted with a Minerva 233cc engine, similar to the contemporary Triumph’s. Yet, initially at least, BSA seemed happy to supply frames and rolling chassis for others to bolt Minerva engines on to. Instead, BSA set about designing and developing their own motor in house, a long gestation period indicative of how they wanted to be certain it would be reliable, economical and fast enough to become the market leader.

In 1906 BSA took over the former National Arms and Ammunition Company’s (aka the Royal Small Arms) factory in Sparkbrook, and a year later the Eadie Manufacturing Company in Redditch, makers of cycle parts almost as famous as BSA’s. This would prove to be a BSA trait – buying up the local competition. In 1910 BSA acquired the Daimler Motor Company just as they were about to enter the motorcycle business.

BSA CARS BEAT MOTORCYCLES INTO PRODUCTION

Dudley Docker – father of the later (in)famous Sir Bernard – joined BSA’s board in 1906 and was appointed deputy chairman in 1909. He had made a spectacular financial success of a merger of five large rolling-stock companies in 1902, and so became the leader of the period’s merger movement. Believing he could buy in the missing management skills lacking within BSA, he started merger talks with Daimler in Coventry. Daimler, alongside Rover, was then the biggest British car builder, and immensely profitable. The attraction for Daimler shareholders in joining forces with BSA was its apparent stability. So in 1910, BSA purchased Daimler with BSA shares – but Docker, who brokered the deal, either ignored or failed to predict the outcome of the pairing.

Nothing was seemingly done to make the factories work together, the two remaining separate and almost wilfully uncooperative: hints of what was to come when BSA absorbed Triumph. Docker officially ‘retired’ as a BSA director in 1912 following a 1909 report on the merger by BSA’s investigation committee, although he was allowed to install Lincoln Chandler as his replacement. In 1913 Daimler employed 5,000 workers to manufacture just 1,000 vehicles, an indication that things were not well. And BSA continued to produce cars of their own, some using Daimler engines.

Torpedo-bodied 3309cc Daimler, first registered in December 1913.CHARLES 01

From 1907 to 1914 BSA built a range of six cars in various forms, but all with steel bodies and rear-wheel drive, powered by 4-cylinder engines ranging from 2596cc to 5401cc. Production started in 1907 with the 18/23HP, joined by the range-topping 25/33HP between 1908 and 1911. The larger models were based on the 1907 Peking-Paris Itala, the car that had won the race of the same name. It was an astounding and rightly celebrated race, starting at the French embassy in Peking on 10 June 1907, with winner Prince Scipione Borghese’s Itala arriving in Paris on 10 August.

In 1910 BSA’s range gained the 15/20HP and 20/25HP cars – really just re-badged Daimlers – and in 1912 all car production was transferred to Daimler’s Coventry home, the range reduced to a single model, the 13.9HP with a 4-cylinder 2015cc motor, also briefly sold by Siddeley-Deasy with a different radiator cover as the Stoneleigh. The bodies built at Sparkbrook were among the first to be all metal, while BSA/Daimler also supplied engines, gearboxes and rear axles for other Siddeley-Deasy cars. In 1914 war stopped car production, although BSA would return to four- (and three-) wheelers in 1921.

THE FIRST BSA MOTORCYCLE

Meanwhile Triumph, a few miles down the road and close to BSA’s car factory at Coventry, had proved the value of motorcycle manufacture. They had moved swiftly to develop the idea of a bicycle frame with a Minerva engine, and were soon building 1,000 motorcycles a year in a new, purposebuilt factory. By 1905 there were 21,121 motorcycles registered in the UK, and in 1908 Triumph launched their first motorcycle designed and built completely in house. Its 300cc motor was rated at 3HP and offered a 45mph (72km/h) top speed, three times what a horse and carriage could manage. By 1910 Triumph were building 3,000 motorcycles a year, and the company’s founder, Siegfried Bettmann, had become Birmingham’s mayor and a British citizen. However, his German heritage loomed large and he felt compelled to stand down once war seemed inevitable.

And so finally in 1910, BSA entered the lucrative and prestigious motorcycle market with a single model that would remain a standard for many years to come, reflecting the quality of materials and design. This first model had a vertical single-cylinder 3.5HP engine, with a chain-driven magneto, sprung forks and the excellent finish associated with BSA’s bicycles. Within six months from launch, BSA’s new motorcycle was selling well, the machines easily distinguishable from rival marques with their yellow and green-painted tanks. A rear-hub, two-speed gearbox was soon added.

Older restoration of a 1913 model, very similar to the original 1910 BSA 3.5HP.YESTERDAYS ANTIQUE MOTORCYCLES

First shown at the 1910 Olympia Show, London, for the 1911 season, the entire production run sold out in 1911, 1912 and 1913. Initially priced at £50, it was also available with a ‘free’ engine, referring to the double cone clutch in the rear hub at £56 10s (£56 50p). To put these prices in perspective, in 1910 average annual earnings were around £70 for men and £30 for women working a fifty-five-hour week.

The original BSA 3.5HP TT (Tourist Trophy) model of 1910–1913 in period.

In 1913 Kenneth Holden, BSA’s chief test rider, won the company’s first race on what was claimed to be a standard production 3.5HP model at Brooklands, averaging 60.75mph (97.77km/h). The following year, six of eight BSA entrants finished the Senior TT races. The 1914 meeting was the first to make crash helmets compulsory, and was also the first to start at the top of Bray Hill, close to the current starting point on Glencrutchery Road. BSA’s best result was a twelfth place for one D. Young in a race dominated by Cyril Pullin’s Rudge.

For 1915 BSA offered a choice between the original 499cc 85 x 88mm 3.5HP model and the long-stroke 556cc 85 x 98mm 4.25HP Model H. This latter was advertised as being especially suitable for sidecar work, now available directly from BSA for the first time. The Model H also had the three-speed BSA gearbox with foot-controlled clutch that was introduced in 1914, and a twin-barrel BSA carburettor. Both models could be had in a chain-cum-belt version or in all chain drive with encased chains, which made the machine £3 5s (£3 25p) more expensive.

The 1913 3.5HP models A, B, C, D and E were all now also available in France, along with three versions of BSA’s Duco sidecars. For 1915 the 556cc 4.25HP model could be had with a three-speed gearbox and, although this Model K production ceased in 1916, it resumed after the war and continued into the 1920s. Development continued with other models joining the range, including the three-speed chaincum-belt model ‘K’ and the all-chain model ‘H’, as well as several well designed sidecars. Until well into the 1930s, various versions of this model were added, adapted or, inevitably, discontinued.

From the final year of the original Model K run in 1916.BENJAMIN HEALLEY/MUSEUMVICTORIA

The Model K still looks remarkably similar to BSA’s first 3.5HP model, proof that the design was pretty much right first time.RODNEY START/MUSEUMSVICTORIA

1922 BSA 556cc Model H.BONHAMS

BSA dropped civilian motorcycle manufacture during World War I, focusing on their traditional manufacture of guns. 1914 would have been a frenetic year at BSA even without the war. The bicycles and motorcycles were popular, with worldwide demand expected to exceed the previous year. The first prototype car had been produced in 1907, on sale the following year, marketed under the BSA Cycles banner. The company sold 150 in 1909, but it is clear that the new diversification was considered unsuccessful, as an investigation committee reporting to the main board listed many failures of management and poorly organized production of the cars. This led to the successful bid for the Daimler car factory, although the two marques remained separate.

However, the arms department remained flat out fulfilling government orders, one of the most important being for the US-designed Lewis machine gun, for which the company held sole European manufacturing rights. Unsurprisingly this demand continued throughout World War I.

The average BSA production for the years prior to the war had been some 135 weapons each week. By the peak of the war 10,000 rifles were leaving Armoury Road every week, including, by the end of the first industrial-scale war in history, 145,000 Lewis machine guns. This massive increase in production called for factory extensions, with three new four-storey blocks rising at the end of Armoury Road. In 1915 work commenced on a four-storey ‘New’ building for Lewis gun manufacture, expanding BSA’s portfolio to five factories. Anyone walking the full length of each of the 60ft (18m) wide workshops would cover a total of two miles (3.2km).

BSA-built Lewis MK1 light machine gun, circa 1914. P1914 Pattern, .303in calibre, gas-operated.COLLECTION OF AUCKLAND MUSEUM TAMAKI PAENGA HIRA, W1492

Other equipment produced for the military included motorcycles, the first folding bicycles, machine tools, aircraft components, gun locks, shells and fuses. Daimler supplied most of the cars, ambulances and commercial vehicles to the military, including the engine and transmission of the world’s first tank. At the peak of the war the factories owned by the BSA group were employing nearly 20,000 people, compared with the pre-war total of 6,500.

After the Armistice it was decided to put the company’s three main activities under separate management, and so three new subsidiaries were formed. BSA Cycles handled bicycle and motorcycle production at Small Heath and Redditch; BSA Guns continued small arms work at Small Heath; and BSA Tools worked in the Sparkbrook factory at the business of small tools, jigs and special-purpose machines. Daimler remained a separate entity, albeit under BSA’s ownership and answerable to BSA’s main board.

Before World War I, Britain had been the world’s economic superpower. With rapid growth and a vast empire, the country benefitted from significant wealth and resources, but still wasn’t ready for the economic impact of the biggest conflict in history. When the war erupted in the summer of 1914, Britain faced market panic and an unprecedented financial crisis. Not only did the government need to reassure the markets, it had to prepare itself for the almost unimaginable economic demands of war on an industrial scale, a scale never seen before in terms of either monetary or human cost.

The government turned to direct taxes – on property and income – on a far greater scale than ever before. In 1913 income tax was only paid by 2 per cent of the population, but during the war another 2.4 million people became liable, so that by 1918, four times as many people were paying income tax as before the war. How this money was spent – or used to repay loans – was therefore now decided by government rather than the people who earned it.