6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

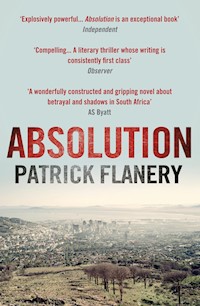

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Winner of the Spear's First Best Book Award, 2012 Longlisted for the Desmond Elliott Prize, 2012 Longlisted for the Guardian Book Award, 2012 Longlisted for the Green Carnation Prize, 2012 Shortlisted for the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, 2014 In her garden, ensconced in the lush vegetation of the Western Cape, Clare Wald, world-renowned author, mother, critic, takes up her pen and confronts her life. Sam Leroux has returned to South Africa to embark upon a project that will establish his reputation - he is to write Clare's biography. But how honest is she prepared to be? Was she complicit in crimes lurking in South Africa's past; is she an accomplice or a victim? Are her crimes against her family real or imagined? In the stories she weaves and the truth just below the surface of her shimmering prose, lie Sam's own ghosts.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

First published in Great Britain in hardback and airport and export trade paperback in 2012 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Patrick Flanery, 2012

The moral right of Patrick Flanery to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 0 85789 200 3

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 0 85789 201 0

Ebook ISBN: 978 0 85789 663 6

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZwww.atlantic-books.co.uk

For G.L.F.

Contents

I

Sam

Absolution

Clare

1989

Sam

Absolution

Clare

1989

Sam

Absolution

Clare

1989

Sam

Absolution

Clare

Sam

Absolution

Clare

1989

Sam

Absolution

Clare

1989

Clare

II

Sam

Absolution

Clare

1989–98

Sam

Absolution

Clare

1998–99

Sam

Absolution

Clare

1999

Sam

Absolution

Clare

1999

Sam

Absolution

Clare

1999

Sam

Clare

I

Sam

‘I’m told we met in London, Mr Leroux, but I don’t remember you,’ she says, trying to draw her body upright, making it straight where it refuses to be.

‘That’s right. We did meet. Just briefly, though.’ In fact it wasn’t London but Amsterdam. She remembers an award ceremony in London where I wasn’t. I remember the conference in Amsterdam where I spoke, invited as a promising young expert on her work. She took my hand charmingly then. She was laughing and girlish and a little drunk. I can see no trace of intoxication this time. I’ve never met her in London.

There was the other time, too, of course.

‘Please, call me Sam,’ I say.

‘My editor says nice things about you. I don’t like your looks, though. You look fashionable.’ She draws her lips back on the final syllable, her teeth apart. There’s a flicker of grey tongue.

‘I wouldn’t know about that,’ I say, and can’t help blushing.

‘Are you fashionable?’ She spreads her lips again, flashes her teeth. If it’s supposed to be a smile it doesn’t look like one.

‘I don’t think so.’

‘I have no memory of your face. Nor of your voice. I’d certainly remember that voice. That accent. I don’t think we can possibly have met. Not in this lifetime, as they say.’

‘It was a very brief meeting.’ I almost remind her that she was drunk at the time. She’s affecting to look uninterested in the present meeting, but there’s too much energy in the boredom.

‘You must know I’ve agreed to the project under duress. I’m a very old woman, but that doesn’t mean I intend dying any time soon. You, for instance, might well die before me, and no one is rushing to write your biography. You might be killed in an accident this afternoon. Run down in the street. Carjacked.’

‘I’m not important.’

‘Quite so.’ There’s a lick of a smirk on one side of the mouth. ‘I’ve read your articles and I don’t think you’re an imbecile. Nonetheless, I’m really not optimistic about this.’ She stares at me, shaking her head. Her hands rest on her hips and she looks a little clumsy, at least clumsier than I remember. ‘I would’ve chosen my own biographer, but I don’t know anyone who would agree to undertake the task. I’m a terror.’ There’s a hint of the girlishness I saw in Amsterdam, something akin to flirtation but not quite, like she’s hoping a man will find her attractive simply because he’s a man, and I have to admit she still has a kind of beauty.

‘I’m sure lots of people would jump at the chance,’ I say and she looks surprised. She thinks I’m flirting back and smiles in a way that looks almost genuine.

‘None that I would choose.’ She wags her head at me, a reprimanding schoolteacher, staring down the famous nose. I may be tall, but she’s taller still, a giant. ‘I’d write my autobiography, but I think it would be a waste of time. I’ve never written about my life. I don’t entirely believe in the value of life writing. Who cares about the men I loved? Who cares about my sex life? Why does everyone want to know what a writer does in bed? I suppose you expect to sit down.’

‘Whatever you prefer. I can stand.’

‘You can’t stand the whole time.’

‘I could if that suited you,’ I say, smiling, but the flirtatious mood has passed. She pouts, points to a straight-backed chair and waits until I sit, then chooses a chair for herself on the other side of the room, so that we’re forced to shout. A cat wanders past and jumps on to her lap. She removes it, putting it back on the floor.

‘Not my cat. My assistant’s. Don’t put in the book that I’m a cat lady. I’m not. I don’t want people thinking I’m a mad old cat lady.’ There’s a picture on the back of her early books – the publicity shot used for the first ten years of her career – in which she holds a baby cheetah, its mouth open, tongue sticking out as her tongue does now. It suggests the suckling toddler, or the stroke victim. ‘My British publisher insisted on the stupid cheetah,’ she’ll tell me later, ‘because that’s what an African writer was supposed to have, the wild clutched to her bosom, suckling the continent, all those tired imperial fantasies.’

‘What form do you anticipate this taking?’ she asks now. ‘Please don’t imagine I’m going to give you access to my letters and diaries. I’ll talk to you but I’m not going to dig out documents or family albums.’

‘I thought a series of interviews to start.’

‘A way of getting comfortable?’ she asks. I nod, shrug my shoulders, produce a small digital recorder. She snorts. ‘I hope you don’t imagine that we’re going to become friends over the course of this. I won’t take walks with you in my garden or visit museums. I don’t “do drinks”. I won’t impart the wisdom of the aged to you. I won’t teach you how to live a better life. This is a professional arrangement, not a romance. I’m a busy person. I have a new book coming out next year, Absolution. I suppose I shall have to let you read it, in due course.’

‘I defer to you.’

‘I’ve read your articles, as I said. You don’t get things entirely wrong.’

‘Perhaps you’ll be able to correct some of my mistakes.’

Clare did not answer her own door when I arrived. Marie, the beetle-eyed assistant, delivered me into a reception room that overlooked the front garden and the long drive, the high beige periphery wall mounted with barbed wire shaped and painted to mimic trained ivy, and the electronic gate closing out the road. Security cameras monitor the property. Clare has chosen a cold room for our first interview. Maybe it’s the only reception room. No – a house this size will have several. There must be another one, a better one, with a view of the back gardens and the mountain rising above the city. She’ll take me there next time, or somehow I’ll manage to find it on my own.

Her face is narrower than her pictures suggest. If there was a fullness in her cheeks five years ago in Amsterdam, the health has receded and now her face is wind-cracked, a lake bottom in drought. It looks nothing like any of the photographs. Her unruly squall of blonde hair has silvered, and though it’s thin and brittle it still has some of the old lustre. Her abdomen has spread. She’s almost a very old woman, but doesn’t look her real age – more like sixty than whatever she really is. Her skin is tanned and the line of her jaw has a plastic tension. Despite the slight hump in her back, she tries to remain erect. I feel a flash of anger at her vanity. But it’s not my place to judge that. She is who she is. I’m here for something else.

‘I hope you’ve brought your own food and drink. I don’t intend to feed you while you feed off me. You may use the facilities at the end of the corridor on the left. Please remember to lower the seat when you’ve finished. It will encourage my sympathy.’ She narrows her eyes and seems to be smirking again, but I can’t tell if she’s joking or serious.

‘Are you going to record these discussions?’

‘Yes.’

‘Take notes as well?’

‘Yes.’

‘Is it on?’

‘Yes. It’s recording.’

‘Well?’

‘I’m predictable. I’d like to start at the beginning,’ I say.

‘You’ll find no clues in my childhood.’

‘That’s not really the point, if you’ll forgive me. People want to know.’ In fact, almost nothing is known about her life beyond the slim facts of public record, and the little she’s condescended to admit in previous interviews. Her agent in London released a one-page official biography five years ago when requests for information became overwhelming. ‘Both sets of grandparents were farmers.’

‘No. My paternal grandfather was an ostrich farmer. The other was a butcher.’

‘And your parents?’

‘My father was a lawyer, an advocate. The first in his family to go to university. My mother was a linguist, an academic. I never saw much of them. There were women – girls – to look after me. A succession of them. I believe my father did a fair amount of pro Deo work.’

‘Did that inform your own political stance?’

She sighs and looks disappointed, as though I’ve missed a joke.

‘I don’t have a political stance. I’m not political. My parents were liberals. It was to be expected that I would also be a liberal, but I think my parents were “liberals” in the reluctant way of so many of their generation. Better we should speak of left-wing and right-wing, or progressive and regressive, or even oppressive. I am not an absolutist. Political orientation is an ellipse, not a continuum. Go far enough in one direction and you end up more or less in the place where you started. But this is politics. Politics is not the subject at hand is it?’

‘Not necessarily. But is it difficult, do you find, to engage in a critique of the government, as a writer?’

She coughs and clears her throat. ‘No, certainly not.’

‘What I mean is, does being a writer make it more difficult to criticize the government?’

‘More difficult than what?’

‘Than if you were a private citizen, for instance.’

‘But I am a private citizen, as you put it. In my experience, governments mostly take very little notice of what private citizens have to say, unless they say it in unison.’

‘I guess what I’m trying to ask – ’

‘Then ask it.’

‘What I’m trying to ask is whether you think it’s more difficult to criticize the current government?’

‘Certainly not. Just because it’s democratically elected doesn’t grant it immunity from criticism.’

‘Do you think that fiction is essential to political opposition?’ I regret the question as soon as it’s out, but sitting in front of her all the carefully formulated questions I’ve spent months preparing seem impossible to ask.

She laughs and the laugh turns into another fit of coughing and throat-clearing. ‘You have a very strange idea of what fiction is meant to do.’

I stall for time, feeling her stare at me as I study my maze of notes. I naively assumed it would all go so smoothly. I decide to ask her about the sister; there’s no denying the importance of politics there. As I’m trying to frame the question in my head, she clears her throat again, as if to say, Come along, you must do better, and I rush into another question I didn’t mean to ask.

‘Did you have any siblings?’

‘You know this, Mr Leroux. It was the climax of a turbulent period. It’s a matter of public record. But I absolutely will not talk about my sister.’

‘Not even the bare facts?’

‘The known facts of the case are on file in the court records and countless press clippings. No doubt you’ve read them. Everyone has read them. A man acting alone, he said. The court found that he was not acting alone, though no one else was arrested. Like so many others, he died in police custody. Unlike so many others, he had actually committed a crime – at least he never denied doing it. I can add nothing else except the experience of the victimized family and that is not new material. We all know how people suffer over the unexpected, violent death of a family member. It is fundamentally no different for the family of a murdered innocent or the family of an executed criminal. It is vivisection. It is limb loss. No prosthetic can substitute. The family is crippled. That is all I wish to say.’

*

Though it’s only supposed to be our second meeting, Clare can’t or won’t see me today. Instead I go to the Western Cape Archives, park on Roeland Street, and nod at the car guard who’s sheltering in the shade of a truck. He gives me a subservient smile and makes some kind of sound of assent. I find myself always on edge, expecting the worst. At the airport I was a foreigner, but a week later, in the market yesterday, I was already a local again. Over a display of lettuces, a woman addressed me, expecting a reply. A decade ago I might have come up with the right words. I had to shake my head. I smiled and apologized, explaining that I didn’t speak the language, didn’t understand. Ek is jammer. Ek praat nie Afrikaans nie. Ek verstaan jou nie. I’ve lost too much of my Afrikaans to be able to answer. I didn’t know what to say about the lettuce or the fish, the vis. She looked surprised, then shrugged and walked away, mumbling sharply, assuming perhaps that I knew but was refusing to speak her language.

The Archives have been housed on the site of a former prison for nearly twenty years. The car guard watches as I walk up the steps and through the green grille of the old gate in the nineteenth-century outer wall. Inside there are shabby picnic tables and plantings, and the new structure, a building within a building. I sign the register, put my bag in a locker, and carry my equipment to the reading room. The woman behind the desk, a Mrs Stewart, is uncertain at first what it is I want. She looks vaguely alarmed when she understands, but nods and asks me to take a seat while she sends someone to look for the files. All her sentences rise at the end, in a tone that questions everything without questioning directly. A few years ago, the staff might have let me do my own digging in the stacks – friends had such luck, finding things they weren’t supposed to find. Now everything is more organized and more professional, but also a little less hopeful.

The other people in the room all appear to be amateur genealogists working on family histories. When the stack of brown folders with bold red stamps appears on my table I feel the others staring, wondering what kind of files I might be consulting, no longer confidential but still bearing that mark. I take out my camera and tripod and photograph page after page throughout the morning.

At lunchtime, two women from the reading room approach me in the lobby.

‘Are you working on family history?’ one of them asks, her voice rising like Mrs Stewart’s.

‘No. It’s for a book. I’m looking at the files of the Publications Control Board. The censors.’

‘Ohhh,’ the other one says, nodding. ‘How verrrry interesting.’

We talk for a few moments. I ask about their research. They are sisters, investigating their ancestors, trying to track down the right Hermanus Stephanus or Gertruida Magdalena over centuries of people with the same names.

‘Good luck with your researches,’ the first one says as we part on the steps. ‘I hope you find what it is you are looking for.’

I give the car guard what I think is proper. It always seems like too little or too much. Later, I ask Greg what he thinks. I trust his opinion because I’ve known him since we were students in New York, and because he’s the most morally and socially engaged friend I still have in the country. When I told him I was coming back, and that my wife would be joining me later in the year to take up her new assignment in Johannesburg, Greg insisted I stay with him for as long as I needed to be in Cape Town.

‘It can never be too much because they need it more than you,’ he says, balancing his son on his knee. ‘Just like if your hire car gets stolen or somebody takes the radio or the hubcaps – you have to tell yourself, whoever took it needs it more. It’s the only way to live with yourself.’

‘I don’t ever want it to look like charity.’

‘Think of all the fuckers who only give them fifty cents and can’t be bothered. Money isn’t an insult. There’s nothing wrong with charity. Not everything has to be payment for services rendered, however informally. And if you’re a tourist you owe them a little more.’

‘I don’t think of myself as a tourist any more. I’m back now.’

‘You haven’t been local for a long time, Sam, no matter what shirt you wear or the music you listen to. And who’s to say you’re going to stay in the long run? Sarah’s post lasts for – how long? – only eighteen months?’

‘Three years if she wants it.’

‘But then you’ll go somewhere else. That means you’re a tourist. You don’t have to feel bad about it. Just remember it.’

‘And how much do you give?’

‘No, see, the thing is, I give less than I expect you to give because I give every day and have been giving for years. I employ a nanny who comes six days a week, a gardener who comes twice a week, a domestic who comes three times a week, and I give soup packets to the old man who comes to my front gate every Friday. I give my domestic and my nanny money to put their kids through school. I buy the school uniforms. I pay for their medical aid. When I park in the city, I don’t give the car guards as much as I’d expect you to give because I give so much already, and even that isn’t enough, you know. And I don’t give food to people who come to the house any more, except the old man, because he’s never drunk. So I’m one of the fuckers I hate. But you tourists, you’ve got to give a little more.’

He speaks quickly, his son playing with the beads around his neck. ‘Dylan, don’t pull Daddy’s beads.’ He looks up at me, smiling. ‘I was thinking, let’s go to the Waterfront this afternoon. There’s a new juice bar open and I feel like shopping. We’ll leave Dylan with Nonyameko. We can see a movie afterward.’

*

Another day. Clare shows me into the same room as the one we used for our first interview. This time she has buzzed me in through the gate and opened her own front door. The assistant must have the day off. We sit again in the same chairs. The cat passes through the room, only this time it takes to my lap instead of hers. Purring, it drools on my jeans and digs its claws into my legs.

‘Cats like fools,’ Clare says, straight-faced.

‘Can we go back to your sister?’

‘I knew you weren’t going to let Nora stay dead.’ She looks weary, even more drawn than the first time. I know that her sister’s story is a detour from the main route. This is not the real story I want, but it might be a way of getting there in the long run.

‘Was your sister always political?’

‘I think she regarded herself as apolitical, like me. But, that’s not quite fair. I’m not apolitical. I’m privately political. But if one chooses a public life – either by career or association or marriage – that’s another matter. She chose a public life by marrying a public figure.’

‘A writer’s life is not a public life?’

‘No,’ she says, and smiles – either condescendingly or, I flatter myself, enjoying the parry. ‘It was unconscionable to take an apolitical stance in this country at that time, as a public figure. She was a victim of her own naïveté. She should have known she was marking herself for death. But she was the firstborn. Our parents made mistakes. Perhaps they left her crying in the crib instead of comforting her. Or they were strict where they should have been trusting. She always resented that I was allowed to shave my legs and wear lipstick when I was thirteen, to have skirts above my knees, to bleach my schoolgirl moustache. It was obvious the same standards did not apply to me, and she saw that. Our parents held her under their thumbs until she was sixteen. She did not go to university. Marriage was an escape from authoritarian parenting into an even more authoritarian culture. I was luckier.’

‘You were educated abroad.’ I know all this. I’m laying down the foundations. Everything else will rest on this.

‘Yes. Boarding school here, then university in England. A period in Europe after that.’

‘And then you returned home, at a time when many in the anti-apartheid movement – writers especially – were beginning to go into exile.’

‘That’s correct. It was before I had published. I wanted to come back, to be a part of the opposition, such as it was.’

‘Do you resent those who emigrated?’

‘No. Some had little choice. They were banned, they or their families were threatened, and some were imprisoned. Or they left for a brief while – to study overseas – and found that because of their political activities they could not return, or simply they realized it was easier in many ways to stay in England or America or Canada or France, and so much the better for them, I suppose, if that’s what they wanted, if that is what they felt they needed to do for themselves. I was not threatened, for the most part, and so I stayed – or rather, I returned and stayed. Is this going anywhere, this line of questioning? What can it say about me?’

When we met in Amsterdam she was drunk on the adulation, and on quantities of champagne. As a result, she was effusive and open-handed then, or seemed so maybe only because she was away from home and being celebrated. She pretended it was her birthday and took a magnum of champagne from the conference reception. At the bland tourist hotel where she was staying, she pleaded in halting Afrikaans for the concierge to get some glasses from the restaurant so she could toast her birthday with her friends, old and new. The concierge tried not to laugh at her language, but it had the desired effect.

I was one of the group then, a new friend. Given the champagne, it shouldn’t surprise me that she has forgotten our first meeting, or that she imagines it was in London, at an awards ceremony instead of a conference. She’s an old woman. Her memory can’t be perfect.

I find it difficult, though, to reconcile the writer I so esteem in print, who took my hand with such grace in Amsterdam, with the woman sitting across from me now. There is open mockery on her face. It triggers a flash of memory that I instantly suppress. I can’t allow myself to think about the past, not yet.

Absolution

It was not the usual kind of slow waking in the middle of the night, from the bottom of sleep. Clare’s bladder was not full, she had consumed no caffeine the previous day. Her window was open, but noises from outside did not, as a rule, ever bother her sleep. Instinctively, she knew something was wrong. She was hyperventilating when she woke and her heart was beating so loudly that if anyone had been in the room it would have betrayed her.

For years she had resisted an alarm, insisting that locks were adequate; anyone determined enough to break through deadbolts and safety glass and burglar bars was worthy of whatever bounty they might choose. But now, how she wished for the alarm, and the kind of bedside panic button that her friends and her son, her scattered cousins, had all chosen to install. She knew, too, that the sound could not have come from Marie, who would be asleep upstairs on the top floor. It had come from below. If Marie had gone downstairs, Clare would have heard her pass in the corridor.

Trying to slow her heart rate, she said to herself, There is silence, there is only breeze, an old mantra she had learned as a girl. The curtains played around the security bars. It was not valuables that worried her. Anyone who wanted them could have the electronics, such as they were, even the silver, the crystal, if thieves cared about such things any more. It was confrontation that terrified her, the threat of guns, and of men with guns. There is silence. There is only breeze. One, two, three, four, slow, six, seven. She had nearly calmed herself back to sleep when she heard the unmistakable swing of a door on its hinge, metal rotating against unlubricated metal, and the bottom of the door catching and vibrating against the coir mats in the foyer downstairs. And above there was movement, a creaking floorboard. Marie had heard it, too.

Clare grabbed for the phone in the darkness but when she put the receiver to her ear there was only a hollow silence. Although she had no cellphone she could not answer for Marie, who might be trusted to have a solution. How long since the door against the mat? Seconds? Thirty seconds? Two minutes? A smell began to work its way upstairs, sharp and astringent, chemical, not a smell of her home. And then another sound, pressure on the first stair, a loose board, and a collective intake of breath, or was that her imagination? She could throw her door closed, but the key for the lock had been lost long ago; she would be unable to escape out the window, there was no space under the bed where she might hide, the wardrobe was too full, there was no closet in her bedroom. The courageous thing would be to sit up in bed, turn on the light and wait for them to come, or to shout, ‘Take what you want, I don’t care!’, but she had lost her voice, and her body was paralyzed. She would have screamed if her throat had let her.

More seconds, a minute, silence, or perhaps she was too distracted to hear. There was a granite stone on the floor which she used as a doorstop, almost a small boulder, and she hoisted it from the floor and into the bed, thinking – what? That she would hurl it at her attackers? Could sticks and stones still repulse men, or did it take harder stuff? These were things she suddenly felt she ought to know.

As she adjusted the boulder in her arms, four hooded men appeared before her, their reflections in the glass of the framed photograph on the wall opposite her bed. They passed in single file down the corridor, carrying stunted guns in their gloved hands. The guns were in fact a sick relief, less intimate; death would be quick. She was no stranger to the power of guns.

The last of the four men turned, looked into the room, and sniffed the air. His nostrils were congested. She could hear it as she shut her eyes tight, pretending to sleep, hoping that consciousness had no odour. She could smell him, pungent and sharp, and the metallic reek of the gun and its oils. Her heartbeats were so loud, how could he not hear them? He did hear them, turned, looked into the corridor for his fellows, but they had gone upstairs already – a shuffle, a scuffle, Marie subdued.

His weight came down on her, gloved hands, balaclava over the face, and the sound of his congested breathing. All of a sudden the stone in her hands was on the floor in a single movement, and he pressed down against her, felt for her, felt his way into her with one hand, the other, the waxed leather glove of it, over her mouth, the suffocation, her nostrils almost blocked, her heart roaring.

No, she had imagined that.

But she could smell him and the metallic reek of the gun. Her heartbeats were so loud, how could he not hear them, standing there at the threshold? But then he withdrew from the doorway, rejoined the others, and crept further down the corridor.

They would have been watching the house, known that only two women lived there, two women unlikely to have guns. They would have known there was no alarm, no razor wire or electric fence and, crucially, no dogs.

Clare felt the boulder, pale and heavy in her arms, resting alongside her. It was wet with perspiration and smelled of earth. She had dug it out of the garden’s old rockery to make way for a vegetable patch. If only the men would whisper to each other, just to let her know they were still there. She thought they were at the opposite end of the corridor, and then was certain of it when the board of the first stair leading to the top floor sighed under the pressure of an intruding foot. God! She must cry out and warn Marie! But she was choked, her throat swollen. Air would not come. The chords would not vibrate. Everything was thick and hard about her.

And then, deafeningly, four bright, explosive shots, low growls, and a fifth, deeper shot, a sixth, bright like the first, and then a rush of feet past her door. The wall opposite her bed exploded in a shower of plaster, knocking the framed photo to the floor, shattering glass across the wood and rugs. There was a final quick shot, a groan and feet pummelling down the stairs, doors slamming, and then silence.

It was not a dream, but she woke from it to find Marie standing next to her.

‘They’ve gone. I chased them.’

‘I didn’t know you had a gun.’

‘You wouldn’t get an alarm,’ Marie said.

‘I will now.’

‘I’m going to the neighbours, to phone the police.’

‘Did you kill anyone?’

‘No.’

‘You missed?’

‘No. I aimed for their firing arms.’

‘You got them?’ Clare asked

‘Yes. One wouldn’t give up. I shot him again. And then the others came at me, and I shot another one of them again. That was all my ammunition.’

‘You were lucky.’

‘I’ll be back in a few minutes.’ Marie hovered near the door, assessing the glass on the floor, the mounds of plaster, the exposed beams in the wall, the outer stucco. The extent of the damage would only be evident in daylight.

‘Are you sure they’ve gone?’

‘They drove away. They were really very stupid. I wrote down their car registration before they came upstairs. They were parked just outside the house.’

‘It was probably stolen.’

After she heard Marie leave, locking the door downstairs, Clare sat up in bed, her throat still dry and hot. How dare Marie keep a gun without telling her? How dare she fire shots in Clare’s house? How dare she assume so much?

Clare had not been so close to firing guns for years, not since she had spent the holidays at her cousin Dorothy’s farm in the Eastern Cape, and the foreman had been killed in an attack, Dorothy wounded. The two Great Danes had been killed, too, and it was only the next morning when they were certain the danger had passed that they went out and dug ditches for the dogs and buried those huge, sleek bodies inside the compound. Danes do not have long lives. They wrapped the body of the foreman in potato sacks and put it in the back of the truck. Dorothy sat next to the man’s body, her leg stretched out and still bleeding. Clare had driven half an hour on dirt roads, then over the pass to the hospital in Grahamstown. Surely there had been others with them, perhaps her daughter? Her memory was only of the bleeding cousin, the dead foreman, the dead dogs, and the invisible attackers. Her daughter could not have been there. By then, Laura had already disappeared.

Clare did not have the stomach to see if there was blood in the corridor, though she knew there would have to be, blood like battery acid, burning into the rugs and floorboards, impossible ever to remove.

The police confirmed that the deadbolts and doors had not been forced, and Marie insisted that she had remembered, as she always did, to check the locks before going to bed; it was as much a part of her nightly habit as flossing her teeth. Besides, she had a mania about security, so she would not have had a lapse, even on a bad day. The telephone line had been cut at its point of entry to the house. Clare stood in the kitchen, her pyjamas covered with a white robe, hair pulled back into a severe knot. She was trying to listen to the policeman questioning Marie, but no one came to question her. It felt as though they were ashamed of Clare’s presence. Women were not meant to be giants. Police flashes flared in the upstairs corridor, accompanied by the high electronic whine of cameras. Forensics experts were dusting and collecting samples. She felt a coward.

If the crime had been so professional in its execution, then perhaps petty criminality was not the explanation; petty criminals, even violent criminals, would not have the kind of equipment that would open a lock without any detectable signs of force. Apart from blood on the floor and gunshot wounds to the plaster of her bedroom wall, her house was untouched. The damage had been done in the ‘gunfight’, as she felt she must call it, in a half-ironic tone that would drive Marie mad in the following weeks. During the gunfight, she would begin a sentence, or I feared that gunfight might be my last experience of the world and it seemed such a waste, such an aesthetic failure.

Only one thing appeared to have been taken.

‘There is something missing,’ she told the uniformed officer who was leading the investigation.

‘Missing?’

‘My father’s wig.’

‘I don’t understand.’

‘The tin box containing my father’s wig. He was a lawyer. I kept it on the hearth. It has been taken.’

‘Why should someone wish to take your father’s wig?’

‘How should I know?’

‘Can you describe it?’

‘It was a painted black tin box with my father’s wig inside. The wig he wore when he argued cases in London. Made from horsehair. I don’t know its value. There were more obviously valuable things they might have taken.’

‘What colour was the wig?’

‘White. Grey. It was completely ordinary, as barristers’ wigs go. Like you see on television. Old movies. Costume dramas.’

‘It is a part of a costume?’

‘No. Yes. That isn’t the point,’ Clare said, trying to check her exasperation.

‘Would you like it back?’

‘Of course I want it back. It belongs to me. It can have no meaning for anyone but me.’

‘Except maybe a bald person. You are not bald. Perhaps the person who took it is a bald man. A bald man would need a wig more than you.’

‘That is a ridiculous thing to say. Should I not give a statement?’

The officer stared at her through pale jelly eyes.

‘A statement? I was told you saw nothing.’

‘Don’t you think you should ask me whether I saw anything? I saw things. I saw the intruders, their reflections.’

Clare was told to go back to bed, to one of the guest rooms. Walking upstairs, she passed little plastic shrines, police evidence tents marking drops of blood, snaking all the way to her bedroom door. She could not remember coming downstairs, nor could she remember having seen blood, but the tents suggested this was impossible; there was blood everywhere, and the smell of the invaders came back to her: synthetic, chemical, a kind of orange disinfectant, a bathroom cleaning fluid or deodorizer. Those men had cleaned themselves before they attacked; they knew what they were about. When they left, she was certain, they did not disappear into the waves of numberless shacks that stretched out beneath the mountain to the airport and beyond; they went to private hospitals where questions would not be asked, and then home to wives or girlfriends who would tend their dressings with quiet discretion.

Dawn burned visibly through a crack in the exterior wall, wood and plaster riven by the shotgun blast. Clare was allowed to retrieve the photograph from the floor; although its frame had been broken and the glass shattered, she found that by some miracle the antique print itself was intact, almost unharmed, except for a small scratch in one corner. In black and white her sister Nora stared, stern-mouthed, not at the camera, but into the distance, looking out, imperious, through horn-rimmed glasses, her forehead shaded by a ridiculous white hat, the fashion of many decades earlier. Though she was not middle-aged when the picture was taken, Nora wore a dress of white polka dots against a pale background – probably pink, Clare thought – with satin rosette buttons. It was not a young woman’s cut, dowdy rather than demure. The polka dots of the dress matched her pearl earrings. Nora’s shoulders rubbed against another woman in a light herringbone coat and black straw hat decorated with ostrich feathers. Both looked smug, chins jutting forward, jowls already forming. Clare did not recognize the other woman; they were all interchangeable, sitting in their reviewing booths at identical party rallies. That was how she liked to remember her sister, buttressed against history, in denial of the currents of history, firm-mouthed and frowning, a year or two before her assassination. It was comforting to think of her that way, to imagine her static and immobile.

Marie was beside her again, panting, smelling of wet grass. ‘Of course now you will have to move. They know they can get at you here. It’s too easy.’

‘I will have an alarm. Better burglar bars,’ Clare protested.

‘You need walls. You cannot stay in this country without walls to protect you. Walls and razor wire, electrified. Guard dogs, too.’

There was no doubt that Marie was going to win this battle. Marie, after all, had risked everything. Marie, the assistant, the employed, the indispensable, must be allowed to determine their future domestic arrangements.

‘Marie, what was the car?’

‘I gave the police the registration number.’

‘But what make? What model? Was it old or new?’

‘New,’ Marie hesitated. ‘A Mercedes.’

‘Yes. I thought it would be something like that. You will make appointments with estate agents, tomorrow, won’t you?’

Clare

You come out, across the plateau, running close to the ground, find the hole in the fence you cut on entry, scamper down to the road, peel out of the black jacket, the black slacks, shorts and T-shirt underneath; you are a backpacker, a student, a young woman hitchhiking, a tourist, perhaps with a fake accent. Soon it will be dawn. But no, I fear this isnt right. Perhaps it wasnt there, not that town not the one on the plateau, but the one further along the coast at the base of the mountains, and you have gone overland to hide your tracks, not through the centre of town, not where anyone will see you at night, men coming out of bars, remembering in days to come the young woman, taut and determined, hurrying alone in the night. You went overland, up the mountain, circling round the north side of town, up through the old indigenous forest. How many hours walk? twelve kilometres or more, and thats if you kept near the road. Run, roll, slide over and down the mountain through the forestry land, the plantation, the even rows of tall pines, a grid of growth, into farmland, wide fields, the mountains behind you, the sea in front, and come down to the crossroads, where others linger in the streetlights, women and men, children, people waiting for a taxi or a relative. An old woman with a child tied to her back scrambles up over the rear fender of a vehicle, helped inside by the other passengers as it drives away, ghosting along the coast road on its innocent journey.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!