8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

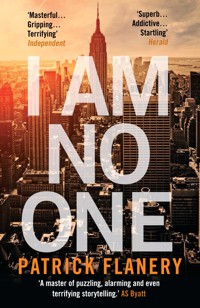

Shortlisted for the Dublin Literary Award 2016 Jeremy O'Keefe, a middle-aged Professor, returns to his native New York after a decade teaching at Oxford, and quickly settles into a lonely rhythm of unfulfilling lectures and long, silent evenings. His quiet world is suddenly shaken by a series of encounters with a strange young man who presumes an acquaintance, and the arrival of three mysterious packages. And when a haunting figure starts to linger outside his apartment at night, his chilling conviction that he is being watched is seemingly confirmed. As Jeremy's grip on reality shifts and turns, he fears that he will never know whether he can believe his experiences, or whether his mind is in the grip of an irrational obsession. I Am No One explores the world of surveillance and self-censorship in our post-Snowden lives, where privacy no longer exists and our freedoms are inexorably eroded.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Title page

I Am No One

Patrick Flanery

ATLANTIC BOOKS

LONDON

Contents

Title page

Dedication

NOVEL BEGINS

NOVEL ENDS

Acknowledgments

The Author

Copyright

Dedication

For AEV & GLF

I

AM

NO

ONE

NOVEL BEGINS

At the time of my return to New York earlier this year I had been living in Oxford for more than a decade. Having failed to get tenure at Columbia I believed Britain might offer a way to restart my career, though I always planned to move back to America, imagining I would stay abroad for a few years at most. In the interim, however, America has changed so radically—by coincidence I left just after the attacks on New York—that I find myself feeling no less alienated now than I did during those long years in Britain.

Although I acquired British citizenship and owned a house in East Oxford on the rather optimistically named Divinity Road, which becomes gradually more affluent as it rises to the crest of a hill, Britain has no narrative of immigrant assimilation, so for my British colleagues and friends and students, it mattered little that I was legally one of them. First and last, I was and would always be an American. Perhaps if one comes at a younger age total acculturation is possible, but as a man in his forties my habits were too firmly in place to undergo whatever changes might have allowed me to become British in anything other than law.

When I was fresh out of my doctorate at Princeton, New York University was not one of the places I would have chosen to work, but I was thrilled when NYU’s History Department approached me to apply for a professorship and even happier when I was offered the position, assured at last that my years away from home were finished. It is surprising how much displacement can alter the mind, and while I went to Britain entirely of my own accord, I became restive after the first few years and increasingly resentful that I was being denied—it seemed to me then—access to a fully American life. I blamed my former colleagues at Columbia and whatever machinations had led to my not being awarded tenure and having thus to begin afresh as a rather lowly sounding Fellow and University Lecturer at one of Oxford’s older Colleges, which, though founded in the fifteenth century, does not attract the brightest students or have the largest endowment.

Nonetheless, I came to see it as a comfortable place to be, despite the workload being substantially greater than at a comparable American institution since Oxford has continued to teach students individually or in small groups, and there is an ever-expandable duty of pastoral care unlike anything in American academia. I became accustomed to the College chef sending me lunch in my rooms if he was not too busy, often including some tidbit (or as the British say, titbit) from the previous night’s High Table dinner. There were excellent wines in the College cellars and life ticked on as it had for centuries, with few changes other than the admission of women, which some dons in my time still regarded as an ill-thought-out modernization that had, they insisted, altered the character of Oxford irremediably.

I was lucky with the property market and before returning to New York this past July sold the house on Divinity Road for a staggering million dollars’ profit, which I invested in a house and some land overlooking the Hudson River a couple hours north of the city, while taking up NYU’s generously subsidized housing in the Silver Towers on Houston Street. Beautiful this apartment is not, but it is a five-minute walk to Bobst Library and I have relished being back in a city that feels global in a way Oxford certainly did not despite the great number of international students and scholars hustling around its quadrangles.

Coming home, of course, meant knowing that I would see my daughter more than once or twice a year, as was our custom during my time in Britain. My loss of tenure coincided with the breakdown of my marriage, though the two were unrelated and no one was really at fault. Nonetheless, it had felt at the time as if there were doubly good reason to seek new opportunities, not only because my career in American academia was finished, so far as I could tell, but because my marriage was also over.

A few weeks ago, just months into my first semester back in New York, I had a meeting scheduled with a doctoral student to whose committee I had been assigned. Life in Oxford has produced a kind of informality in my relations with students, graduate students in particular, and so I proposed meeting Rachel at a café on the Saturday afternoon before Thanksgiving. It was one of a series of Italian-themed places on MacDougal Street that claimed a lineage longer than seemed likely, but I enjoyed its cheap coffees and the variety of authentic pastries for sale in the glass display case. It helped soften some of the culture shock I have been feeling on my return to America, allowing me to believe for a moment that those markers of European life towards which I have grown fond remain accessible even on this side of the Atlantic. Accordingly I made Caffè Paradiso a regular stop in my weekly life, as it provided the kind of quiet and spacious venue where friends and students could be met and conversation lingered over without the sense that a waiter or waitress was going to rush us out the door. It has more atmosphere and élan than any of the chain coffee shops and less hectic bustle than the faux-artisanal places so packed that one has to compete for a table and then feel the pressure of other guests helicoptering with eyes peeled for the first movements building to a departure. Caffè Paradiso is not chic or hip but it has understated style and that, I suspect, is what has kept it in business for so many years—either that or it’s a front for money laundering, which is always a possibility in this town.

Rachel was usually prompt in our communications and we had met once before, in September, for what in Oxford I would have called a supervision but which now was perhaps better called a meeting or, if that felt too businesslike, then simply coffee. In the intervening two months I had heard little from Rachel until she sent me a completed draft of a chapter. This work, on the organizational history of the Ministry for State Security in the German Democratic Republic, was very assured. I had only a few suggestions for how she might fine-tune her methodological framework but wrote to say I thought it would be productive to meet again before the holidays.

Since I am always early wherever I go I had brought a book with me, though I did not expect Rachel to keep me waiting. She gave the impression in our first meeting and in all our subsequent communications of being a young woman of exceptional meticulousness and punctuality, even punctiliousness. Several days prior to our previous meeting she had written to confirm the time and place before I had done so and when I arrived for that appointment, in the coffee shop near the southeastern corner of Washington Square, she was already waiting for me.

On this second meeting, just a few weeks ago, I ordered an Americano, took a table near the window, and opened my book. I cannot now remember what the book was, it might have been Paul Virilio’s Open Sky, or something of that sort, but I soon found that I had read ten pages and when I looked at my watch it was nearly a quarter past four, fifteen minutes after the appointed time of the meeting. I took out my phone, an antiquated black plastic wedge unable to send or receive emails, but at least, I thought, I could send Rachel a text message, as I sometimes did to my daughter if I was arranging to meet her and got stuck in traffic. When I scrolled through my list of contacts I was surprised to discover that Rachel’s name was not among them, although I was certain I had entered her details when we met in September.

Another ten minutes passed and I took out my phone again, checked to be sure I had not overlooked her number, perhaps it was filed under last name instead of first, but there was nothing. It was possible that at some point I had accidentally deleted the entry, my fingers are not as dexterous as they once were and the tiny keys on my phone are difficult for me to punch accurately, or maybe, I reasoned, the memory of putting Rachel’s name and number into the list of contacts was nothing more than willful invention or a false memory of an intention left unfulfilled.

I had been nursing the coffee and now decided there was no point in waiting longer so I raised the cup to my mouth and in so doing caught the gaze of a young man, perhaps in his late twenties or early thirties, sitting at a table across from me. I cannot say how long he had been sitting there, whether he had already been present when I walked in or if he had arrived after me, but he nodded or perhaps did not nod but made some acknowledgment or greeting and then began speaking in a way so casually familiar that I was taken off guard. This is not something that tends to happen in Britain, where suspicion of strangers is so deeply ingrained in the national psyche, perhaps from the years of the IRA threat, or even more distantly, from the suspicion of German spies during the Second World War, that strangers often do not even make eye contact let alone speak with one another, unless they are from elsewhere, and then, by happy chance, it becomes possible to bond with someone in a public place, both shaking your heads over the confounding maze of London’s transportation network or the cost of living or the difficulty inherent in walking down the street because whatever laws of left-side walking that might once have been in force have been confused by London’s transformation into an international microstate, and though distant enough from the capital, Oxford is a satellite of this phenomenon, its Englishness gradually giving way to a cosmopolitanism that moves with brutal transformative force. Perhaps the day will soon come when strangers in Britain talk to each other in ways that will feel normal rather than extraordinary.

But here, in New York, on a cold day in November, there was a stranger engaging me in conversation, and because of my habituation to an English attitude of reticence it seemed so astonishing that at first I did not believe he could possibly be speaking to me.

‘Stood up?’

I did a double take, looking round the room. ‘You talking to me?’

‘You talking to me? That’s funny,’ he laughed, ‘like De Niro, right? You talkin’ to me?’

‘Yeah, I suppose so.’

‘So? Stood up?’

‘No. It’s not like that. I was waiting for a student.’

‘Male or female?’

Again, I surveyed the room. The café was not very full and there was something sufficiently strange in the young man’s tone that I was unsure whether it was safe to continue the conversation and thought of ending it right there by excusing myself. If I had any common sense remaining, that is precisely what I should have done, given what has come to pass, but clearly, in retrospect, I had taken leave of my senses, or perhaps, I think now, taken leave of my British senses and allowed the American ones to seize control.

‘Female.’

‘Pretty?’

Once more I looked around, this time to be sure there was no one I knew within earshot.

‘Excuse me?’

‘That means no. You sound British.’

‘I lived there for more than a decade. To the British I always sounded American.’

‘Well, you sound British to me. Anyone else tell you that?’

‘A number of people. Americans tend not to have a good ear. They think that British actor, what’s his name, who plays a doctor on TV, they think he does a faultless American accent. He doesn’t. It sounds like an accent that was cooked up in a laboratory rather than grown from seed, as it were.’

‘See, that’s what I mean. Americans would never say as it were. You totally sound British. That’s awesome.’

‘Thank you, I guess.’

‘So she’s not pretty, the student who stood you up?’

‘She’s attractive enough, but that’s not the point. She’s an excellent student.’

‘But a flake.’

‘No, not a flake. It’s just not like her.’

‘Then call her.’

‘I don’t have her number. Thought I did . . .’

‘Senior moment?’

‘Listen, I’m not that old.’

‘You could be my granddad.’

‘I’m not even fifty-five.’

‘Okay, calm down, I’m just messing with you. What do you teach?’

‘Modern History and Politics, and a senior seminar on Film.’

‘Cool.’

‘Are you a student?’

‘Nope. Not anymore.’

‘You know what I do. Don’t you want to tell me what you do?’

‘Just another corporate shill.’

And that, as far as I remember it, was the end of the conversation. He struck me as not much younger or older than my daughter, with sandy hair and a pale complexion that made him look like a corn-fed Midwesterner, the kind of face that hosts the slightly haunted-looking eyes of poverty from a few generations back—not his parents or grandparents necessarily, but one or more of the great-grandparents, I suspected, had not eaten well for much of his or her life and somehow that hunger had taken hold of their genes and been passed down to the kid who struck up a conversation with me in an Italian café in Greenwich Village at the end of last month. It was a face that reminded me of the portraits by Mike Disfarmer, those sepia photographs of ordinary Arkansas folk, too tanned, most of them lean and a little hungry or hunted looking, as though in hunting to put meat on the table they had at some moment in the chase realized they were themselves being tracked by an unseen predator.

The meeting was not in itself unsettling, although this young man was the sort of person who left me glancing over my shoulder as I walked back to my building in the afternoon dark, and then as I stood in the lighted window overlooking Houston Street—or, rather, staring at my own reflection as I was thinking about the passing traffic outside—it occurred to me just how visible I was, only a few floors up from street level, the blinds open and me standing there, listening to Miles Davis and drinking a glass of scotch because it was, after all, already half past five in the afternoon and it was November and dark and I felt alone, in fact quite lonely, and realizing that the reason I had not ended the conversation immediately, even when it took its stranger turns, was because I had not yet managed to reconnect with my old friends in this city, had in fact allowed those friendships to slide during my years in Oxford, so that now I no longer feel able to phone up the people who were once my intimates and ask them if we could meet for a coffee as easily as I proposed such meetings with my students, female or not, pretty or otherwise. I decided I should invite a small group of colleagues for dinner, then remembered the reason I was feeling unsettled in the first place, and the fact that I had briefly forgotten why I was unsettled compounded my sense of unease. I opened my laptop and there, right at the top of the sent messages in my email, was a message to Rachel that I had apparently written that afternoon, at just past 2pm, so only a few hours earlier, in which I asked her if we might reschedule our meeting until Monday at 4pm in my office because another commitment had unexpectedly arisen and I could not, I was terribly sorry, find a way to get out of it, and would she please forgive me. And there was her reply, which I had apparently read, assuring me it was no problem whatsoever and Monday at 4pm in my office suited her perfectly.

Now, I had no memory of writing the message, or of having read her reply, and while it is true that I was having my first drink before 6pm, it was definitely my first of the day. Moreover, I had not had a drink all week, though one might think that because I have to mention such a thing perhaps I have had a problem in the past, which is not the case either, unlike a great many of my former colleagues at Oxford, a majority of whom I would guess were functional—and some not remotely functional—alcoholics of the kind not readily tolerated in American academe. The point being: I had not blacked out, had not forgotten this exchange with Rachel because of alcoholism, although it would have been reassuring if I had completely blanked out the episode because of something external to my own mind and not because of a black hole in my memory. It may be a point of regret but in those moments in my newly re-Americanized life when I feel suddenly ill at ease or simply lonelier than any contact with students and colleagues can remedy, I phone my daughter, and this is what I did on that Saturday a few weeks ago. I turned down Miles Davis and picked up the phone and asked Meredith how she and Peter were doing.

‘Fine, Dad, a little crazed, to be honest. We have a dinner tonight.’

‘Anyone important?’

‘Yes, but I can’t—I mean, I shouldn’t really say.’

‘Am I untrustworthy?’

‘No, of course not, it’s just, phone lines these days, you never know. Maybe I’m being paranoid. But how are you?’

‘Okay. Something—it’s . . . nothing really. I just wanted to hear your voice.’

‘Come tonight if you like. I could use another person. And it would be good to see you.’

I could not tell whether it was a genuine invitation or if my daughter was simply throwing pity on me, but I made a brief show of protest before accepting. The thought of spending the night alone in that apartment in the Village, or even taking myself out to eat and then going off to see some deeply earnest Iranian or Turkish or even French film at the Angelika or walking an hour up to Central Park just to feel the sensation of moving among other people, to imagine I was not alone in the world, failed and a failure because I had to throw myself into the company of strangers to create the illusion of connection, was more than I could stomach. Such perambulations, all the attempts at distracting myself from my loneliness, only made the sense of isolation worse.

When I accepted the job at NYU I did not give much thought to how this change, my return to a city I still thought of as home despite more than a decade’s absence, would affect my social life, which in Oxford was stuffed with colleagues. Many of them, it has to be said, were foreigners like me, banding together in our shared sense of alienation from the English, or from Englishness, which I gradually came to understand was distinct from Scottishness or Welshness (though the latter is a word one does not commonly hear) and was often conflated in the minds of the English with Britishness. I once heard an anchor on Sky News describe the tennis player Andy Murray as ‘England’s great hope, and he’s a Scot,’ as if the whole country were truly England, only one part of a federal country, and not the United Kingdom. Despite the alienations of Englishness, which is really about the exclusionary quality apparent in some quarters of Englishness, its unwillingness to assimilate its immigrants, I was not, not ever, not even in the first months of my life in Oxford, ever truly lonely. There were endless garden parties and High Table dinners and gaudies and drinks receptions, and it remains a small enough place that the like-minded seem instinctively to seek each other out, making time despite the onerousness of the workload to keep conviviality at the heart of their experience of that ancient city. The socializing, I came to understand, was as much a part of the educational and intellectual atmosphere as the libraries and lecture theaters.

So in the late afternoons or evenings, feeling a sudden void of loneliness in New York—the city I love, a love that sustained me when I was in Oxford, a city I also came to love for its own peculiar charms—I find myself too often phoning my daughter, especially on weekends, and perhaps too suggestively asking if she and Peter have any plans. Three out of five times Meredith invites me to their apartment for dinner or to meet at a restaurant, or I discover that she has an event in the Village or Meatpacking District—a gallery opening or party—and she swings by to see me before heading home. I have learned that my daughter, who until recently I still thought of as a child even though she is married and by all measures successful in her own right, with a gallery bearing her name and a rising reputation, has, like her father, a taste for single malts, and especially for those earthy and almost medicinally peaty ones from Islay. Together we will sit in my living room with Miles Davis or Ornette Coleman on the record player, because I have taken to buying ink-black vinyl LPs in what my daughter calls, with not a little contempt, one of my ‘aging hipster affectations.’ All that remains missing is a Cuban cigar between us, though that sounds unduly Freudian now that I think about it, or might suggest that what I really wanted—what I want, what I most desire now—is a son. Meredith is the greatest joy of my life, and will always be, I remain certain, no matter whoever else may yet—I hope—become a part of my family.

On that Saturday in November when the meeting with my student Rachel did not materialize, I took the subway up to Columbus Circle and stopped in a grocery store in the basement of a building that wasn’t there when I last lived in the city; in fact Columbus Circle has changed so much over the years that it is scarcely recognizable to me every time I return. If I emerge from the subway without thinking where I am, the disorientation is so acute I have to look at a map or ask directions just to find my way onto Central Park South.

Perhaps it’s related to the divorce, or to the fact that I packed up and moved away when my daughter was only thirteen, leaving her in the care of her mother, or even the humbling way in which she and Peter have transformed my own life by granting me access to luxuries I never thought would be within my reach (travel is always First Class, zipping through fast lanes and pre-approval lines at airports, resting in executive lounges before departures and helping myself to free food and drink), but I find it impossible now to arrive empty-handed at her door. How much I owe her, how much I feel I have to compensate for the years of my absence. That night I brought a bottle of Laphroaig because she likes it, though it is neither expensive nor rare, and an autumnal bouquet from that overpriced basement grocery store.

Meredith answered the door and my God, the effect! For a father it was nothing short of breathtaking to see her like that, in an exquisite black dress, a string of pearls, her dark hair swept behind her shoulders, her whole presence perfectly composed in every imaginable way except in the eyes, and there, in her gaze, I could recognize total panic and guessed she had invited me not as a favor, but because she needed help getting through the kind of gathering that would once have been extraordinary to her and to me, but is now meant to be no more significant than any other business dinner. Why she had not invited me in the first place I can only guess; perhaps she thought I would find it boring, or Peter vetoed it, or, after my long absence from their lives, it had not occurred to them, although we have seen each other frequently over the past few months, which suggested to me that a conscious decision had been made at some point—or at some level, I thought, because it has always been clear that Peter regards himself as the ‘decider’ in the marriage—that on this occasion I should not be present.

As I handed Meredith the flowers and scotch she leaned over to kiss me on both cheeks. How sophisticated we’ve become in the space of two generations. My parents would never have imagined greeting anyone with such European flair. But before I could get any further two security men in suits appeared.

‘Sorry, Dad, you understand, no one gets inside tonight without the onceover. You know how it goes.’

The men passed a metal detecting wand around me and patted me down and once I had been given the all-clear, assured that I was unarmed and therefore not a risk to whoever was in the next room, I followed my daughter into the kitchen, which was thronged with cater waiters and a chef. Since my return to New York, and in fact since Meredith and Peter married two years ago, I had never seen my daughter so much as boil water for tea. Usually the housekeeper does the cooking, but for an event like that night’s dinner they needed a larger staff and it was only later that I understood how important the evening was, and what a risk, in a sense, Meredith had taken by inviting me at the last minute (I later discovered there had been a late cancellation, one of Peter’s colleagues whose child fell ill with food poisoning, and I presented myself, as if by fate, to make up the numbers). I don’t know in retrospect whether there was an element of calculation on Meredith’s part but I like to think there was not, that there was and is enough affection between us that she was moved as much by her own need of my support as by a desire to support me, to lift me out of my all too obvious loneliness.

‘I’m so grateful you could come, Dad. I need you this evening.’

‘Don’t be silly, it’s my very great pleasure.’

‘You’ve become so British,’ she smiled, straightening my tie. ‘Would you like a glass of something? There’s champagne.’

‘That would be lovely.’

‘God! So British.’

‘How is that British, sweetheart?’

‘Americans just don’t say lovely in the same way.’

‘Is it wrong? Should I try to change?’

‘No! Of course not.’ She handed me a glass of champagne that had been passed to her by a waiter with whom she communicated by a slight tilt of the head in my direction.

‘Who’s here tonight? Can you tell me now?’

‘Sorry for the subterfuge, it’s a working dinner for Peter. Albert Fogel and his wife, and Fogel’s mother. The rest are all Peter’s colleagues,’ and here she dropped her voice, ‘most of whom I can’t stand, but you know, they were all at the same prep schools and colleges and they’re all millionaires many times over. These are the people who are really running the country, and most of the time they have no idea how pervasive the effects of their power are, but there you go, this is the world we live in.’

It broke my heart a little to hear my daughter sound so jaded and I wondered if marrying into money was responsible for that, not that her mother and I were poor, her mother especially, and one has to acknowledge that Meredith went to one of those colleges and one of those private schools and it was because of that educational access, not to mention her distinctive, slightly old-fashioned beauty, the face of a Vermeer, the creamy pale skin of a Manet, all those random genetic inheritances, in combination with her fine mind and exceptional taste, that made her so attractive to a certain population of wealthy young men who had an eye for beauty but also for intelligence, who could see that my daughter, not spoiled from birth but well looked after, nurtured and kept level-headed, would be a stable partner at least for the first decade of their professional lives. A colleague at Oxford quipped on hearing of Meredith’s engagement a few years ago, one can but hope to see one’s children reach their tenth wedding anniversary: to hope for any more would be foolish, even hubristic. The age of constancy has passed.

That evening Albert Fogel, New York’s newly elected Mayor, was seated next to Peter at one end of the table, the Mayor’s wife next to Meredith at the other, and I was saddled with Caroline, the Mayor’s widowed mother, who fancied herself an artist. The rest of the places were taken up by Peter’s colleagues, most of them either editors at his magazine or at other magazines or newspapers, although I wondered whether they actually called their publications by such old-fashioned names these days, if instead they thought of themselves as the titans of ‘news outlets’ or ‘information platforms’ or even ‘media ecosystems.’

‘And what do you do?’ Caroline asked me over the monkfish, by which time I had spent half an hour listening as she rhapsodized about Meredith’s brilliant career, and what a bright light she was already becoming and how she hoped that perhaps I might put in a good word for her with my daughter, because in her day she had been lucky enough to have shows at some of the big galleries, and she was still producing art, not yet out of the game, she was working on a series of paintings about the aging human body, ‘self-portraits of my own isolated body parts. And what do you work on, Jeremy?’

‘Twentieth-century German history and political thought, some political theory. I wrote a history of East Germans who worked as coerced informants for the Stasi.’ Mrs. Fogel nodded, but I sensed I had lost her attention. ‘Now I’m teaching a course on film, and I guess that’s what I’m most interested in at the moment, perhaps it’s a sign that my brain is beginning to atrophy, that I no longer have the patience for the hard archival work and would rather just watch movies.’

‘Film. How interesting,’ she said, and I was certain I had lost her. ‘My first husband was a director. He was always trying to film me in the nude. I finally dumped the schmuck and married Albert’s father. He was a lawyer. Just as prying, you know, but not so invasive. I think he might have been a homosexual. Don’t look so shocked! He was never very interested in sex or even in seeing me naked, and frankly that suited me fine, but God, he wanted to know everything about my mind. It was exhausting but he moved me out to Connecticut, which was heaven.’

‘You don’t like New York?’

‘It’s so dirty, so busy. I hate all the dog crap on the sidewalks. It makes me sick.’

‘I’ve just moved back after more than a decade in Oxford.’

‘Why would you want to come back to New York? Oxford is pretty, so peaceful. I used to dream of having a little English cottage with a thatched roof surrounded by a meadow. Something like Howards End, you know, with the tree and the pigs’ teeth in the bark and all that. So romantic. So English. Why would you leave all that behind? There’s nothing like that here, not in New York, and the American countryside is so wild, so dangerous. You can take a breath and fall over dead.’

‘It’s not quite that bad.’

‘All I know is that I love the pastoral quality of the English countryside, the Constable landscapes, the coziness of it, nothing that can kill you but your own stupidity. Oh, you’re making me want to go! I should plan a trip for next spring, when the bluebells are in bloom. I remember a bluebell wood outside of Oxford, back in the ’60s, and I felt like I’d stumbled into fairyland. Albert was only a baby then and the three of us had this delightful two-week holiday driving around the south of England. How could you bear to leave all that behind?’

I thought of the trucks that thundered past my Oxford house, shaking the windows even though it was a residential street, and the student parties next door that would sometimes require phoning the police, or the banal ugliness of so much of East Oxford, the construction that seemed to go on for years along the Cowley Road, the unstable sidewalks made of one-foot-square concrete slabs that would subside in the rain and flip up to drench my legs, not to mention the drone of the ring road circling the city. There is little truly peaceful about Oxford these days.

‘The truth is, I missed America. And NYU offered me more money and less teaching. And of course Meredith and Peter are here, and my mother is in Rhinebeck. It was about family as much as anything.’ I told Caroline this because people never want to hear that a place about which they have romantic associations is just as mundane and imperfect as anywhere else, and I know that Oxford is beautiful in a way that is quite special, despite its flaws, but I was also still in the first flush of my renewed love affair with New York, with this great global city that seems truly unlike anywhere else in the western world, and that night I did not want to hear anyone trying to convince me that Oxford would have been a better place to see out my professional life, in my cushy College Fellowship and university professorship. Nothing could possibly have kept me from staying despite a desire to do less work and to be paid more money and to see my daughter more than twice a year and to live again in the city that once gave me so much.

I did not think then about all that New York had taken away, namely my wife, my marriage, an unbroken career in America, and thus an uncomplicated sense of what home means. Of course I found Oxford beautiful, particularly on those uncanny long summer evenings, sprawling with friends in the University Parks or punting on the Cherwell, steering the boats over to the shore to picnic on the water as swans floated past, the hawthorns dropping white blossoms. Perhaps the shabbiness around the edges, the ugliness that licked against the idyll, was a large part of why all that remained beautiful seemed so exquisite, so transformative, able to foster a desire to make myself one with the beauty, to soften the cadences of my speech and adapt my vowels. Returning to America I have discovered with ever greater frequency that many Americans no longer see me in the same way, that I have become something other than an American to them, although I know that with work and a studied determination to undo the verbal and behavioral tics I acquired in Britain, I may yet pass as my old self, or a subtly altered version of my old self.

‘I think you’ll find America has changed since you’ve been away,’ Caroline said, leaning to one side as a waiter took her plate. ‘When the Republicans no longer had the Cold War to let them do what they liked, they had to invent a new one, that badly named War on Terror. What they could not have imagined is that the War on Terror, by turning its eye everywhere, even within the borders of this country, laid the groundwork for a new Civil War. That’s what the Tea Party and its ilk want, although they’d call it Revolution probably, but the reality isn’t revolution at all. It’s one part of the population determined to live and govern in a way that’s anathema to most of us. I don’t know, I’m just a painter, and maybe what I’m describing is the very definition of Revolution, but it’s not one with universal support, however much they might want to present it as such.’

As the evening progressed I realized the Mayor’s mother was more intelligent than at first she seemed. She looked and sounded like Lauren Bacall, whom I had once seen stepping into a car on Park Avenue; Caroline had the same elegance and grace and the kind of deep voice that suggested either an unusual physiognomy or else long years of marinating her vocal cords in whisky and cigarette smoke. She must have been in her eighties, so could easily have been my mother, and she spoke in the often irritating way of the aged and coherent, who insist on their wisdom and on imparting their knowledge to those who will listen. I was willing to listen politely for the sake of my daughter and her husband, not that Peter has done much to encourage my affection, I find him a rather stiff son-of-a-bitch, not unlike the Hooray Henrys of Oxford’s Bullingdon Club, the American equivalent of those self-satisfied toffs with no interest in ordinary people and no real understanding of how the poor suffer. The difference with Peter, however, is that his politics and heart are ostensibly in the right place, which is to say, from my perspective, the left, although with the super rich, and I think it’s fair to put Peter in this category, for those people who have been rich from birth, who have, as his mother jokes, been paying taxes since they were in utero, they can never entirely understand the realities faced by most Americans, never mind the realities of the profoundly impoverished people elsewhere in the world, to whom America’s poor would look comparatively well off.

I met the new Mayor and his wife that evening, we spoke briefly over coffee, all of us stepping out onto the terrace despite the cold to look at the lights in Central Park and the glow of buildings over on the Upper East Side. This, I thought, this is why I came back to New York, because I have been nowhere else that affords such urban views. London is a city of great pre-war beauty and much post-war ugliness, Paris for all its splendor can be monotonous and museum-like, Rome is chaotic, Berlin a hodgepodge, but New York has, despite the recent proliferation of new skyscrapers, cracked a kind of urban code that makes it one of the most dynamic cities in the world. Admittedly I have not been to Asia, and colleagues tell me that to see the urban future I have to go to Shanghai and Tokyo and a dozen other cities that will tell me a quite different story. Perhaps one day, although the promise of that kind of travel now grows more and more dim as the days pass and I sit in this room, scribbling these pages and wondering just what kind of future may yet be mine, what the purpose of my account here will be, who will read it, whether it will be little more than an eccentric legacy left to my heirs, or one day soon entered into evidence, a matter to be classified rather than kept public. You who read it, whoever you are, in whatever number, are undoubtedly already drawing conclusions about me, reading between the lines and making assumptions despite my protestations of innocence.

Fogel was charming but I sensed his judgment that I was a person of no great importance. The only reason to chat to me over coffee was because I was the father of his hostess and because he relied on the goodwill of media titans like Peter and his colleagues to convince the city that what he wanted to do, the plan he had to make it a fairer, more egalitarian place, would not undo the economic growth attributed to the policies of his predecessor. We spoke only briefly and he showed no real interest in me. I cannot blame him. What am I but an academic historian, a professor who may teach another fifteen or twenty years, perhaps influence a generation or two of other scholars, although now that future—all aspects of my future—seem genuinely in doubt. Each word I put on paper I imagine may be the last I write in freedom.

When everyone had gone home that night and I was left alone with Peter and Meredith while the staff washed the dishes, the three of us sat down in the den. I thought Meredith might open the Laphroaig and was surprised when she did not, although we had all been drinking throughout the evening, three different white wines, one for each course, of a quality I had come to expect from Peter.

‘Why don’t you stay the night, Dad?’

‘No, I should get home.’

‘Don’t be silly. It’s after one. We have nothing to do tomorrow, so stay. We’ll have a late breakfast.’

‘You’re sure it’s no trouble?’

‘You’re very welcome, Jeremy.’

‘As a matter of fact, I wanted to talk with you about something, although maybe I should leave it until tomorrow.’

‘Go ahead, Dad, I’m feeling wide awake.’

Peter, though, looked exhausted. ‘If you want to go to bed, it’s fine. I don’t have to talk about it now. It’s really no big deal.’

‘No, please, Jeremy, you’ve piqued our interest.’

‘Something slightly strange happened today. I was supposed to meet a student and I confirmed it by email earlier in the week. I saw her after a lecture I gave yesterday and we spoke again about the meeting. So I went to the café at the appointed time and she didn’t show. I walked home and was going to email her to ask why she hadn’t shown up, only to discover that I appear to have written to her earlier today to ask if I could reschedule and she responded saying that was fine. Now the problem is, I have no memory of writing that email asking to reschedule, nor do I remember reading her reply, and yet both messages are there.’

Meredith shifted on the couch, drawing her feet up under her legs and covering herself with a gray wool blanket I remembered having sent them after a trip I made to Stockholm for a conference last year. It was gratifying to see it was in use and had not been stowed in a cupboard, forgotten, or re-gifted to some less affluent friend. ‘I guess that is kind of strange. Have there been, you know, any other incidents like this?’

‘No, sweetheart, not that I’m aware of, which is why I wanted to talk to you about it. Have you noticed anything? Am I losing it?’

‘No, absolutely not. I haven’t noticed anything like that. Have you, Peter?’

Peter shook his head. ‘Honestly, I swear, Jeremy, your memory is better than mine. I haven’t detected anything strange. I mean, you drive me crazy a lot of the time, but that’s not the same.’ He smiled because it was a teasing, generous thing to say, rather than an expression of real irritation. It was the kind of banter that made me like the kid a little more each time I saw him, and I felt he was gradually relaxing around me, accepting me as part of the family, though I had met his parents only a couple of times and had the sense that Meredith was becoming integrated into Peter’s family more completely than he had become a part of ours, perhaps because there was no ‘ours’; there was now my family, which was Meredith and my mother, and Meredith’s mother, who was really on her own, she has no siblings, her parents are dead, so less scope for Peter to become a part of us in the way that Meredith could become a part of them. I felt this as a loss, it is true, because I knew that to a large degree the dissolution of our family was my fault and not Susan’s, although the decline of any relationship is almost always multilateral, and my ex-wife was not without fault.

They tried to reassure me, Meredith and Peter, and by the time it was two in the morning we were all struggling to stay awake and Meredith went in search of something I could wear to bed, returning after a few minutes with a pair of pajamas that had never been worn, as well as a brand-new bamboo toothbrush, still in its packaging, and a razor.

‘Were you expecting me to stay?’

‘We’re prepared for just about any eventuality. Security to the power of ten.’

‘Or more.’

‘Probably a great deal more.’

I wondered whether the guest bedrooms were always made up, or if Meredith had anticipated there might be last-minute guests and had asked the housekeeper, a Dominican woman, to put on clean sheets and set out fresh towels. There was reassurance in taking off my clothes and putting on new pajamas, particularly ones of such lovely quality—lovely, not very American, it’s true, but I can’t get rid of it, nice tastes like Wonder Bread on my tongue—and then sliding in between those high thread-count sheets and pulling the duvet up around my chin, looking out at the lights across the park and knowing my daughter is in such a position that I need never worry about my own security for the rest of my life. This had happened in a way I could not have predicted and with such speed it sometimes threatened to destabilize my sense of our relationship. She was not yet thirty, hardly out of childhood it seemed, and yet she was also a fully functioning adult with a career, with her own business, and with a husband who is one of the most influential men in America, and all of this at such a young age! Youth has somehow effected a bloodless revolution and it is foolish, I know, to imagine that the young people of America are not ultimately in charge. That night I could go to sleep confident that if I woke the next morning and remembered nothing of the previous days or weeks, or had forgotten the sum total of my adult life, then Meredith and Peter would look after me. I would be shipped off to the top facility on the East Coast and until my death I would be contained and cared for, never having to worry if I might end up wandering the sewers of New York City or sleeping in the Amtrak tunnels in which I remember once seeing informal encampments on the way to visit my mother upstate. Whatever happens, I will not be one of the destitute fated to fall off the grid, no matter how much a part of me might now wish that were possible.

The following day, Sunday, we were slow to get up, but when we finally convened, a little after ten that morning, the housekeeper had already made waffles and there was a bowl of fruit salad and hot coffee and The New York Times, satisfyingly thick, all laid out on the white marble kitchen counter. I could see almost at once, however, that Meredith and Peter had been talking and there was something they needed to say, as if they had—this turned out to be the case—made a decision about me in the hours following my confession of the unexplainable lacuna in my memory, or so it then seemed.

They waited until we were alone in the kitchen, in the glassed-in breakfast area overlooking the park. It was not the first time I had stayed with them, but I could see how the longer they lived together they were settling into a pattern of routinized comfort that suggested a pursuit of the ideal, of the best possible way of drinking coffee and eating breakfast and enjoying the beauty of their view, not to mention the beauty of each other. They are, without question, a stunning young couple whose attractiveness is not about youth alone, but about the way they wear that privilege of age without worry, or with worries always mediated by the knowledge that security will, barring a revolution, be permanently theirs.

‘We’ve been talking, and we’d like to arrange for you to see a really great doctor.’

‘My dad has been to see her, Jeremy. She’s one of the top memory specialists in the city.’

‘So you do think there’s a problem with me?’

‘No, Dad, honestly, neither of us has noticed anything. We just think—’

‘Isn’t it better to rule out the possibility of anything actually being wrong, Jeremy? Wouldn’t you rather know, and catch it at an early stage, instead of living with the uncertainty and the worry?’

They both sounded sincere. Sincerity is not one of their failings.

‘Of course you’re right.’

‘Can I make you an appointment for this week? I’m sure we could get you in before Thanksgiving.’

True to his word, Peter arranged an appointment for Monday, when I had no classes and no commitments other than the rescheduled 4pm meeting in my office with Rachel. I was grateful to Peter for leveraging his influence, and I hope, even still, after all that has happened since that week when I first became conscious of the strange changes pressing against the trajectory of my life, that I demonstrated sufficient gratitude for his assistance.

After brunch I went home. Meredith offered to send me in a car and for once I accepted because I was still feeling tired from the late night and I wanted to indulge, if only for another half-hour or so, in the knowledge that someone was looking after me. How different my life would be if I had remained in Britain, if I had not sold that house on Divinity Road but continued to live there in my slightly cramped if comfortable way, making the occasional excursion to some European city and leading what was in many ways a very un-English life, or at least a life not representative of the constricted lives so many people in Britain suffer. Not that I have more space in my NYU apartment, slightly less in fact, and no garden just outside the dining room, but nor do I have the sense of vertiginous insecurity that sometimes came over me in Oxford when I was lying alone in bed and wondering whether the house was locked. In New York, as a white man of a certain age and class, I have tended to feel secure, despite the city’s unpredictability and its problems with police corruption and crime and terror, though Oxford was not immune from terror either, or at least from those who would seek to spread the contagion of terror even to the sleepier corners of the world.

Riding in the back of the black town car down Seventh Avenue, I thought of a Syrian doctoral student who arrived in Oxford almost at the same time as me, and I think of him now, wondering if my brief association with him might have been a foretaste of what was to come. The young man made odd threats against me and my colleagues, demanding special treatment for no better reason than because he had recently been working for Syria’s mission at the United Nations in New York. When his demands were rebuffed he threatened the entire department. At first no one took it seriously, but when the threats escalated I reported the young man to the terrorist hotline that Britain had then set up and within a few days he disappeared and no more was heard of him.

I did not then and still do not regret what I did, and the fact that he disappeared suggests to me I was not mistaken in reporting him to the authorities. It occurs to me now how easily a single tip-off, a phone call lasting no more than five minutes, might change the course of a stranger’s life. Am I, I wonder, any different from the ordinary East Germans who turned themselves into informers for the Stasi? I assumed the young Syrian was a threat but had no evidence other than my suspicions and fears. I remember now that he said something to me along the lines of, ‘things are going to change around here. You’ll see who really runs the show.’ It was perhaps nothing more than a young man’s boast. In fact it sounds, thinking about it once more, like little more than ill-advised swagger, the sort of threat someone who has been on the receiving end of an authoritarian boss might then turn around and use against the next weak person he or she encounters—the kind of boast I can imagine I myself could have made to a senior colleague at Columbia, much to my regret. Perhaps there was nothing suspicious about that young Syrian, but the British security services must have thought otherwise, since he disappeared. It is possible, I suppose, that he was not detained but simply chose to leave. His face came back to me that Sunday as we turned onto Bleecker and suddenly a group of young Middle Eastern men surrounded the car as they crossed the street. I had more or less inoculated myself against seeing threat in a brown face during my years in Oxford, particularly after buying the house on Divinity Road, which required, for the fastest possible commute to my College, walking along the Cowley Road where so many Pakistanis and people from elsewhere in the Muslim world have shops and make their homes, as well as go to worship. From my back garden I could see the dome and white spire of the Central Oxford Mosque and on more than one occasion had to listen to the music of a party in some neighboring garden, melodies and rhythms such that I fancied I might as well have been in Lahore or Istanbul. No, living in Oxford in the immediate aftermath of the attacks on New York and Washington was like having immersion therapy by exposure to the thing one fears most.

There are several doormen who work in my building but the guy on duty that Sunday was a clean-cut Puerto Rican called Rafa.

‘Professor O’Keefe! Package for you.’

From behind the desk he pointed to the area where packages are left, near the mailboxes and the windows looking out on the courtyard between the three buildings. Odd that a package would arrive on a Sunday, but perhaps it had been delivered on Saturday and I had simply failed to check whether there was anything for me.

‘Do you know if this came yesterday, Rafa?’

‘Can’t tell you, boss. I came on at ten this morning and it was here when I arrived. Ignacio was on duty yesterday. You can ask him tomorrow.’