6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

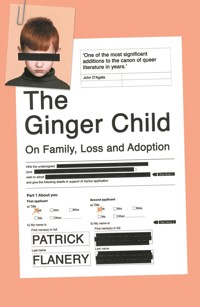

A raw and heart-wrenching literary memoir about a queer couple's attempt to adopt a child. But would you take a ginger child? A social worker asks Patrick Flanery as he and his husband embark on their four-year odyssey of trying to adopt. This curious question comes to haunt the journey, which Flanery recounts with startling candour as he explores what it means to make a family as a queer couple, to be an outsider in a foreign country, to grapple with the inheritance of intergenerational loss, and to discover that the emotions we feel are sometimes as mysterious to ourselves as to others. Reviews For TheGinger Child: 'It is shocking, and consoling, in its honesty.' - Emma Brockes 'this is a book to be savoured' - Jackie Kay 'A rare, brilliant and essential exploration of adoption'- John D'Agata This uniquely powerful book moves deftly between heartbreaking memoir and illuminating meditation on parenting, adoption and queerness in contemporary culture, stopping along the way to consider recent science fiction film, camp horror television, fiction and visual art. At the end, which could also be the beginning of a new journey, Flanery asks whether we might all imagine ourselves as ginger children-fragile, sensitive, more easily hurt than we think possible, but with the hope that we are also survivors, with greater powers of resilience than we know.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Ginger Child

Also by Patrick Flanery:

Absolution

Fallen Land

I Am No One

Night for Day

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Patrick Flanery, 2019

The moral right of Patrick Flanery to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Interior: Monkeyboy © Kate Gottgens, on p. 136 is reproduced with kind permission of the artist

Hardback ISBN 978 1 78649 724 6

E-book ISBN 978 1 78649 725 3

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

Mothers

Birth

Questions

Terry

Nuclear

Genetics

Surrogates

Hugo

Stages

You

Worry

Hotel

Queer

Max

Queered

Citizen Ruth

You

Searching

Annie

You

Envy

Prometheus

Envie

Alien: Covenant

Alpha Romeo Tango

‘Interior: Monkeyboy’

Loss

Sara and Catherine

On Paper

You

Child Parent Child

Hidden

Matching

Me

Introductions

After

Ordinary

You

The Ginger Child

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Notes

ginger, n. and adj.1

A. n.

1. a.

The rhizome of the plant Zingiber officinale, which has a distinctive aroma and hot spicy taste, and is used in cooking and as a medicinal agent.

B. adj.

1.

c.

Of a person: having reddish-yellow or (light) orange-brown hair, and typically characterized by pale skin and freckles. Hence more generally: red-haired.

3.

[Short for ginger beer. Cockney rhyming slang for queer.] … (frequently derogatory and offensive). Homosexual.

*

ginger, adj.2 (and adv.)

Origin: Formed within English, by back-formation. Etymon: gingerly adv.

…

Cautious, careful; gentle… Also: easily hurt or broken; sensitive, fragile.

Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, 2017

Names and other details have been changed out of respect for the privacy of certain individuals.

MOTHERS

Today, many days, I play a private game, imagining hypothetical mothers. Not my own mother, who I know well. Not mothers who would bear a child, abandon it, relinquish it, or have it taken away, a child we would then adopt, but mothers who would bear a child for us, altruistically.

I look through profiles of friends and acquaintances on social media, think of possibilities, past promises.

When I see your picture with your husband and children, I remember how you and I pledged to have a child together if we were both still single at thirty-seven. I wonder if you ever think of that now.

At the time, when we were in our twenties, did you want me to say, ‘let’s have a child now, let’s not wait’? Although that was what I felt, I could not muster the courage to say it for fear you would laugh at me in your charming, heart-breaking way.

A couple of years ago, when we saw each other for the first time in more than a decade, it felt to me that not even five minutes had passed. Although we both now have husbands and you have children and another pregnancy would be a risk not worth taking just for the sake of a friend’s desire to have his own child, I cannot help imagining what might have been.

Today, of course, the idea tips us over into the fantastic. But I still think about it, what you having a child for me and my husband, what raising that child, what the closer bond created between us, would do to all of us, for the good.

But I do not expect.

You understand, I hope.

I see your picture, with your two children, your wife, and think about the processes you went through, different anonymous donors, speculating about which traits your children may have inherited from those unknowable men, the way the two girls are so wildly different in appearance and character, both of them dark-haired while you are blonde, as if your genes had left no visible trace on either of them. I think about your generous assertion, after giving birth to the first child, that if you were younger you’d happily get pregnant for us but you could not conceive of a second pregnancy, the first was so difficult and you were getting old, your body could not take the further damage, the risk was so great. And then, a few years later, you decided to try again, for yourself and your wife, and were successful.

I look at you building a career, negotiating the frustrations of distant family and complexities of sibling relationships, doing it all with such an elegant determination to get things right, while worrying whether you will have the life you want in the end.

Does it ever occur to you that we could reach a mutually beneficial agreement that would give you something in exchange for the someone we so desire? Such wondering about your own wondering leaves me feeling poorer and meaner, uglier, because it should not be about money, any of this, but only about love.

You will undoubtedly have your own child or children, and why want the complication of another child, even a child not biologically yours but with that connection nonetheless, of having carried her or him in your body for nine months, a child who would appear before your own children as the first child, the child you relinquished because he or she was not yours to keep.

How would you explain that, if we did it?

And would it be so difficult to explain, in the end?

Would it require no more than saying, I had that child for them because I could? But she is not my child in the way that you are my children, you might say to your sons, your daughters, if that day ever came.

I pass you on the street as you are talking on your phone, saying, ‘No, Kev, honestly, I got it. Don’t you understand I’m serious when I say I don’t want a kid?’ What would happen if I waited for you, a stranger, to finish your conversation and then asked in the politest, least threatening way I could muster, ‘But would you have a kid for us? I’d pay you. I’d pay you however much you want, even if I don’t have it, even if the law won’t let me, I’ll give you whatever you think you need to make it worth your while, I’ll rob banks to pay you,’ and I know, in that thinking, how deep my desperation has become.

It feels as if I spend whole days out in the world, on trains and trams and undergrounds, sniffing out fertility and sympathy and if not willingness then openness and radical politics and the selflessness such an act would require, to do this without paying scores of thousands of dollars to lawyers and clinics.

And yet I still imagine, you know, robbing a bank if that’s what it takes.

(Not that I would.)

I meet you for the first time in fourteen years and although you are now, like me, in your early forties, you are single and unlikely ever to have a child of your own. Sitting across from you over coffee I think, why would it not be possible? I think this and at the same time I know: this will not happen.

Yet my brain oscillates between the wondering and the knowing, and when it does not oscillate, holding one in dominance over the other, it holds both the wondering and the knowing (this cannot be) at the same time, concurrent, living the cognitive dissonance of desire and despair.

I look at you, and you, and you, and you, having one child, two, three, more, sharing photos of them online, expecting us, your friends, to click and like and love and comment with amusement and joy and commiseration when things get difficult, and I think, does it ever occur to you that you have been given a gift you might have shared? By which I mean not the children, obviously, but the exceptional ease with which you and your partners have them.

And this thinking goes on, stretches over years, loops through the lives of all these possible candidates, friends and acquaintances, strangers, colleagues, and the horror of it is that I cannot bring myself to ask the question, to face the disappointment when each and every one of you would, I am certain, say no.

Some of you will read this and see yourself, or not see yourself, and some of you not among the yous will see yourself anyway. And I suspect that some of you, whether you are among the yous I mean or not, will feel anger, irritation, but perhaps also sympathy or compassion, and I know that you might feel things I cannot begin to predict or imagine, that your own capacity for cognitive dissonance, for the wondering and the knowing to settle alongside each other concurrently in your own minds, may outstrip my capacity to imagine what you feel.

And I am sorry if that happens: I am sorry it is happening to you, and also: I am sorry, but that is just what happens, because I desire what you might provide, have provided, still (some of you) may yet provide, no matter how impossible that provision feels or seems to you and me and everyone around us.

*

I suggest to my husband that we send out an email, blind-copying everyone we would potentially consider, explaining what we are doing, what we are seeking, how we expect no reply, if the answer is no we do not want to hear it articulated, silence would be preferable so that when we see you again we can carry on with our relationships as if nothing had ever been said.

But if the answer is yes, then, you know, please write.

It is too great a thing to ask, he says. We cannot ask.

Over time, as months and years pass, I begin to wonder why we could not make ourselves more bohemian. We know performance artists and writers and queer scholars and activists. We are proximate to a milieu that I’m convinced could help facilitate our parenthood, bring forth a constellation of people who might be a community of parents to the child for whom I long.

But perhaps our petit-bourgeois childhoods, our attachment to things, our sense of our own marginality here as immigrants, however privileged we are compared to some, militates against us embarking on a form of family-making that would demand from us and everyone involved a sense of radical fluidity and flexibility. Stable, stuck in our ways, habit-lovers, we are neither radically fluid nor flexible. Surely the bohemian family of multiple parents and multiple homes, in which my own choices about parenting would always have to accommodate the choices and feelings of others in this notional constellation, would drive me mad.

As if the desire itself has not already.

I catch a clip of that film from the 1990s about the murderous rich boy lovers. One turns to the other, man to man, sneering, if you could get pregnant you would, wouldn’t you?

Of course I would.

BIRTH

You and I are standing on the stump of a tree in your front yard, on the parkway, that strip of lawn between sidewalk and street. Your house is a few doors down from mine. We have just exchanged vows, though I am only two years old, you a year older, and now we each unroll a baby from our matching raglan shirts and hold these plastic infants up for our mothers’ approval and laughter.

This has been your idea, the marriage and instant reproduction, you coaching me through the language of vows, providing your dolls as our children. How traditionalist of you to think marriage should precede reproduction, how precocious to understand babies emerge from the lower abdomen.

But how radical, too, that you should suggest I, a boy, might give birth just the same as you.

Forty years later, I find you online, click through the family photos you’ve made publicly available, your three children, flesh and blood, not plastic, three children who look uncannily like my memory of you, the five of you now living in the same city as your parents and your sister and her husband and their three children, all of you so close.

What might have happened if your family had not moved away? We would never have been lovers, because that would have been, for me, an impossibility, for you an exercise in futility and frustration. But perhaps we could have been the sort of friends who remain close throughout their lives, rather than people who drift from such closeness into total strangerhood, so that I wonder now: do you remember me, and our first family? Does someone, you or your mother, still have those children we carried?

QUESTIONS

But would you take a ginger child?

We are sitting in a café in the midst of a London park on a bright autumn day. Mary, the brunette social worker who has asked this question, is in her fifties. It is November 2012.

My husband and I glance at each other, bewildered.

We would take a ginger child, a black child, an African, an Asian, an Australian, a South Pacific Islander, a Caribbean, a Latin American, a Native North American, an Eastern European. We would take a mixed-race child, a Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu or Atheist child.

In this moment, we are open to a child from anywhere, of any race, religion or national origin.

I am American, white, of German, English and Irish ancestry (as far as I know). My husband, Andrew, is South African, white, of Dutch, French and English ancestry (as far as he knows). Given the long history of my family on the North American continent, and of my husband’s family on the African continent, we assume our genetic makeup may be more varied than genealogy and family lore suggest.

This, and the fact of our coming from racially and ethnically heterogeneous countries, makes us believe in our capacity to parent a child of any background or identity or race. And after setting aside the idea of making a family through surrogacy, choosing instead to pursue adoption, we are willing to consider any relatively healthy child.

Yes, of course, we say, we cannot understand why red hair is so often reviled in Britain. We would absolutely take a red-haired child.

Mary is relieved.

We have a ginger child now, very sweet boy, two years old, but no one wants him, she says.

Because he has red hair? I ask, again bewildered.

Parents think ginger children will be badly behaved, she says.

Fears of the Celtic. Fears of the fiery. Misplaced fears. Nothing but rank prejudice. We would take the ginger boy now, this instant, except we are only at the beginning of the process. We have not been vetted or approved as adopters.

What are the red lines? Mary asks. What wouldn’t you be able to cope with?

Serious physical or mental disability, I say.

Autism, Andrew says. Sexual abuse.

What about neglect? Mary asks. Or physical abuse?

We both hesitate, but yes, we could handle a child who has been neglected or physically abused, although in this moment I am not thinking about what the long-term effects of abuse and neglect might be, the degrees of severity, the way neglect itself is also a form of abuse, since abuse means, first, a chronic corruption of ‘practice or custom’, according to my dictionary, and what is neglect but a failure of practice to care?

Physical disability seems clear-cut. I know that I could not look after a child with reduced mobility, who struggled to move through the world. I imagine a paraplegic, a quadriplegic, a child confined to a wheelchair, and know I am not up to meeting such needs.

I know we could not handle a child with a serious chronic disease, such as HIV. I know I could not handle a deaf or blind child. This is not a judgement against children who fit any of those categories, but an honest acknowledgement of my own and my husband’s limitations as potential parents. We would find it too difficult.

Why would we find it too difficult?

The first answer, one to which I will return over the coming years, is that the red lines of capacity and incapacity have been drawn by Andrew’s and my individual traumas, but also by my desire, problematic as I know it is, for us to turn ourselves into that camera-ready middle-class same-sex couple with a toddling baby crawling across the lawn we don’t have in front of the house we don’t own.

I know that desire is selfish, perhaps even unethical, and I wonder if our reservations, all those red lines, disqualify us from being parents at all. Couples with biological children have no guarantee that things will go well, and here in the first meeting about adoption we find ourselves ticking boxes, saying no to one category of complication or disorder or life experience and yes to another.

This form of calculus arises from being made to think about what it means to construct a family without the biological capacity to reproduce. Surely people who conceive biological children are never made to consider what they will or will not be able to handle before ever laying eyes on the child, unless an ultrasound or amniocentesis reveals complications before birth, or unless you know that you or your partner is likely to pass on a particular illness. Which is not to say that such couples don’t consider it, but they are usually not forced to do so.

If you are not asked questions about your own capacity as a parent before being allowed anywhere within sight of a child who might one day be yours, it is possible you never consider what you might or might not be capable of handling.

Imagine a doctor asking a couple struggling to conceive: how would you manage if your daughter ends up with autism? How will you cope if your boy develops ADHD? What is your network of support? How many close friends live near you? How much do you trust them? How many family members live within an hour of you? Who can you call for help in the middle of the night? What kind of leave does your employer offer? What are your financial resources? If you lose your job, will you have the means to meet the needs of your child?

If people were asked these questions, the birth rate would plummet.

Maybe it should.

Being made to think about what you might be capable of handling is enough to shatter every rosy vision of babies crawling over grass in suburban gardens under a clear bright sky. It kills the joy of imagining a family before a solid hope that what you want will even be possible has the chance to take root.

What about serious mental disability? Mary asks. Could you handle that?

Mary’s voice is crisp, cajoling. She has a script. She asks everyone the same questions. Given our answers already, I wonder how she could ask this.

My coffee has gone cold. Young women with babies and toddlers have packed the café since we sat down. A boy is shouting for a muffin. A girl cries.

Mary’s choice of venue, where she meets all prospective adopters, feels like a test. Can we manage to discuss these most intimate questions about parenting and face up to our own childlessness in the presence of so much natural reproduction? Wouldn’t it be more humane to conduct this interview in private?

The truth is, her question about mental disability throws me into murkier territory.

We want a child under the age of eighteen months, preferably as young as possible. How, at that age, can one be certain what disabilities might be at play? We do not require a genius, but we do want someone who will grow to independence. We want to be parents, not lifelong caregivers, and in this way, there is something selfish in our desire to adopt, although the entire British social care system almost never acknowledges this. Adopters must hew to a narrative of altruism: we put ourselves forward to do the job that the state is unable to do. Which is not to say that Andrew and I are unmotivated in part by an altruistic impulse. When we got together a decade earlier, we knew that making a family would not be straightforward. I knew this when I asked him, very early in our dating life, rounding the corner from Broad Street to Turl Street one wet autumn night in Oxford, whether he wanted children. Having decided that I loved him enough to want us to stay together forever, having decided that if children were not part of his vision for his own life then this was not going to work, I had to know. And the truth is, I was not imagining adoption. I was already thinking of alternatives. But perhaps adoption is the parenting role male couples like us are meant by nature to fulfil.

In light of Mary’s question, I ask myself what constitutes mental disability. Is mental illness a disability? Even if it technically is, would I construe it as such?

I could handle a depressed or traumatized child, even one with PTSD, but I could not handle a psychotic one, assuming psychosis would even be apparent in one so young. I know that I cannot spend the balance of my life looking after someone who is seriously mentally ill. I could parent a child with OCD, but not one with autism, unless it was at the very mildest end of the spectrum. I could manage one with ADHD, but not with bipolar disorder.

Epilepsy? No.

Developmental disability? No.

Schizophrenia? No.

Down syndrome, Fragile X? No, neither.

Any serious genetic condition affecting mental ability? No.

Life-threatening nut allergies? Yes.

Why one and not the other? Part of every decision comes down to perception, which itself is determined by social constructions of what each variety of disability or disease or disorder appears to mean. The balance of the decision is produced by being forced, in a café full of mothers and children, to consider one’s own character on the fly, with no chance for reflection.

I know that I am temperamentally disinclined to bend my life towards the management and care of a person with certain kinds of problems. Some problems appear manageable, others do not. And in most cases I am conscious that these perceptions are not necessarily stable or permanent, but highly context specific. This comes in part from living in a country I have adopted, but which has not, I feel, adopted me. I will always be an outsider here, and as someone who is other in multiple ways, I cannot imagine struggling to raise a child with serious medical problems. So I can imagine that if we lived in South Africa, for instance, I might well be prepared to take on an HIV-positive child, but not in Britain. Never in Britain.

Sitting in this café with the grinding roar of a coffee machine and the burble of babies and chatter of mothers and crying of toddlers and sing-songing offers of cake as balm for those children’s anxiousness or sadness or momentary grief, I wonder if all my reservations, each one in turn, should disqualify me from being a parent in the first place. I think of all the people I have heard on television or radio over the years describing the struggles of raising children with exceptional needs, the way so many of them resort to the formulation, ‘we weren’t coping’ or ‘we couldn’t cope’. What do those biological parents do when they realize that their own child’s needs have outmatched their capacity to meet them?

How quickly Andrew and I find the algebra of accommodation comes into play: from imagining an ideal child, an infant willingly given up by its birth parents, a child in ‘perfect’ physical and mental health without reduced capacities, a smiling baby who has been loved and attended to every second of its life – never left to cry itself to sleep, never wanting for food or affection, diaper always promptly changed, read to and cuddled and kissed, hearing songs and going to sleep staring at a mobile hanging above its crib, lovingly bathed and laughed with, soothed and reassured, taken for walks to the park and trips to museums, held up to paintings and works of art to look closely at the details, treated in all the ways my mother treated me as a child – we are forced to consider every possible complication we might face, and the compromises we will inevitably need to make.

This rationalizing happens in the span of a moment in a café crowded with mothers and children.

I have to remind myself how we got here. We were willing to do this because we know other couples who have adopted successfully. Only a few months ago, a friend and her husband adopted a two-year-old girl. A few years earlier, acquaintances in Manchester adopted two boys. I look at their pictures on social media. The boys are healthy. Everyone is smiling. Whatever difficulties they may experience are not presented for an online audience. This is in contrast to some people we know with biological children who sarcastically gripe about the horrors of parenthood (‘kids are the worst’), and others who seem not to be enjoying any of what they’re doing, moaning every time there’s a snow day or school vacation, who have no idea how to fill the hours alone with their children and appear to resent the responsibility of looking after the gift – in some cases many gifts – they have given themselves.

You should not be so ungrateful, not even in jest, I want to tell them.

Mary spends an hour asking us questions and half an hour making proclamations:

It is not important that we are a same-sex couple.

(We didn’t ask whether it was. British law allows for same-sex adoption.)

It is not a problem that I write novels.

(I didn’t think it would be. Why would it? Is writing novels regarded as undesirable in some quarters?)

Although, she has to admit, she wonders what kind of novels I write. She had another novelist who was approved as an adopter, and he wrote gay porn, she titters. As if she thinks all novelists who happen to be men in same-sex relationships must write porn.

No, I don’t write gay porn, I tell her, or any other kind of porn.

Mary tells us that all the children available – nearly all – have been forcibly taken from their parents because of abuse or neglect. In Britain, there is no culture of young mothers giving up unwanted pregnancies. It happens, but only very rarely.

Somehow, this is news to me. And the idea of being presented with a child taken from its birth parents is chilling. How is this approach to forming a family any less ethically compromised than surrogacy?

Although Mary has told us nothing we do not already know, there is a quality in her tone, a patronizing, shaming edge, a desire to shock and put off any prospective adopters still clinging to rose-tinted visions of parenthood, that irritates the hell out of me.

As we walk back to the car, I tell Andrew I cannot do this.

We have to find another way.

TERRY

Terry is four and I am six. Our mothers met each other volunteering. Terry has recently been adopted. He has an older brother, Todd, also adopted. Terry has dark red hair that falls to the nape of his neck. While Todd, adopted from a South Korean orphanage, is calm and sweet-natured, Terry, adopted from the state foster care system, is totally out of control.

Because their parents have to be out of town for a night, Terry and Todd stay with us.

For Christmas that year, I received an electric train set. The circular track is bracketed to a large square panel sealed in green plastic. The train – an engine and half a dozen cars – goes round and round with mesmerizing speed and elegance.

Every week my mother takes me to the Union Pacific corporate headquarters in downtown Omaha to see the exquisitely detailed model trains in the lobby, engines mounted on plinths with buttons which, when pushed, make the wheels turn. We took the train to California and back when I was four, and although the crew forgot to refill the water tanks in Denver and there was nothing but fruit juice and booze until we reached Arizona and the train smelled of vomit and on the way home I lost the stuffed horse with velveteen hooves that my aunt gave me for Christmas, trains remain the most thrilling machinery I can imagine.

I love my train set more than my cardboard brick building blocks and Star Wars action figures, more than all my puppets or stuffed animals. The electric train is the pinnacle of my possessions and waking up to find its huge green track propped behind the tree was the greatest Christmas surprise ever.

Perhaps because I am an only child growing up on a street where everyone else is much older, my playdates with other children, boys in particular, often end badly. I hate sharing as much as I long for friends.

Terry insists on playing with the train. Though I hesitate, my mother says I should let him have a turn. We sit on the floor of my playroom in the basement of our house, a playroom that was the bedroom of the previous owners’ teenage daughter, and which is carpeted with mustard-yellow wall-to-wall shag pile beneath a suspended ceiling of acoustic tiles. Disco seventies chic.

Terry runs wildly around the room. He throws my toys. Somehow, he breaks the train within moments of starting to play with it. Or at least he breaks some element of the electronic mechanism by forcing the train along the tracks.

Bewilderingly, my parents never have it fixed and for years the track and train cars gather dust in a corner of the basement utility room, until eventually, once my attachment to them has attenuated, we sell them at a garage sale with the disclaimer that the set needs repair.

The train is beside the point. My encounter with Terry is the first time I am conscious of meeting someone who is adopted. My mother has explained what this means. She explains, too, that Terry behaves the way he does because he is adopted.

And the association sticks:

An adopted child, I am already conditioned to believe, is a child out of all control.

NUCLEAR

When I phone my mother to tell her that Andrew and I have decided not to pursue adoption, I am surprised at how relieved she sounds.

You know, she says, I was about to adopt a child from South Korea when you came along.

No, I never knew this.

Oh, sure, it was all in the works. I’d been in touch with the agency, we went through the interviews, it was going ahead.

She had miscarried and, instead of trying again immediately, she thought she and my father should adopt.

I never knew about the miscarriage either. How is it that I have reached my late thirties without knowing either of these things? Or did I know them at one point, perhaps a decade or more ago, and found the information so unsettling I repressed it?

I feel a sudden sense of loss for the sibling I never knew, a feeling more like melancholy than sadness or grief, and which leaves me wondering who that other person might have been, or if I myself might have been that other person, arrived earlier, in a different form, a different sex. I try to imagine what it would have been like to have an older brother or sister, whether it would have made growing up with my father easier or more difficult. Or, what would it have been like to have a Korean older sibling? How might that person have shifted our family? Would it have saved us from ourselves, from the triad that was so disastrous for each of us? Might my father and Korean big sister have bonded in ways that would have made my childhood even worse than it was? Would she have resented my arrival and usurpation of her place and taken out her frustrations on me? Or would the Korean child have been enough? Would that girl’s or boy’s arrival have condemned me to nonexistence?

Surrogacy is a good choice, my mother says. It means you won’t have all the complications, all the other people involved. It can just be the two of you and your child. Your own child.

My parents decided early on in their marriage that they would not have children, instead devoting themselves to teaching and journalism and activism. It was the early 1960s. They lived first in California’s San Joaquin Valley, my mother teaching in schools where the children of Mexican farmworkers sat alongside the children of families who had migrated west during the years of the Dust Bowl.

Later my parents moved to Los Angeles, then to Chicago, then Baltimore, each move prompted by my father’s graduate studies or jobs. He wrote his doctoral dissertation on the press coverage of the 1968 protests in Chicago during the Democratic Convention and following Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination. My parents were often participating in those protests themselves, being teargassed and going to bear witness to the murder of Black Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, and finding their community organizing group in Evanston infiltrated by the FBI (or so they suspected).

My mother was teaching in Lincolnwood, Illinois, fighting alongside other teachers for equal pay and the right to wear slacks instead of skirts. They won the battle of fashion but not of finance. At some point in her early thirties, my mother tells me, as my father became ever more consumed by his work, first as a doctoral student and then as a reporter at the Baltimore Sun, she realized if she did not have a child she would spend the rest of her life alone.

As she commuted to work on her master’s degree, she had time to think about this on walks from the train station through Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, keys poking out between her fingers because they lived in a neighbourhood where women had been attacked and murdered, as happened in the alley behind their building on the first night they moved there from Chicago. My parents mistook the screams for a cat fight and only discovered the truth in the morning.

After Nixon’s resignation, they moved back to California because my father, who was being groomed to become the Baltimore Sun’s Washington correspondent, felt compelled to return to the San Joaquin Valley, where my mother had lived since the age of seven, where she did not want to live again, where my father had taken a teaching job without first asking how she felt about it, where they bought a bungalow in Fresno on the affordable end of Van Ness Avenue, known locally as Christmas Tree Lane, where, in due course, I spent most of the first two years of my life, crawling and toddling around a garden that my mother later told me reminded her of Munchkinland and that seemed, from the vantage of my Omaha childhood with its apocalyptic thunderstorms and tornados, its inhuman winters and oppressive summers, like a lost wonderland from which I had been unjustly removed.

I have not asked whether the pregnancy that ended in miscarriage was planned, whether she convinced my father to start trying, or if it was a surprise to him, or a surprise to them both. I have never asked my mother if she was on the pill, or what kinds of birth control she used. If they were about to adopt a child from South Korea, my father must have agreed to this at least. And when I was conceived, had she convinced him to try again, or was it an accident, even a planned one?

I never have the courage to ask these questions.

In a way, I don’t need the answers.