Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

By July 1981 four republican hunger strikers had already died in Long Kesh Prison. A fifth, Joe McDonnell, was clinging to life. To outsiders, Margaret Thatcher appeared unbending; yet, far from the prying eyes of the press, her government was making a substantial offer to the prisoners. On 5 July this offer was given to Gerry Adams in Belfast, and relayed to the prison leadership. In this important sequel to the bestseller Blanketmen, O'Rawe documents the four-year war of words that followed. He interviews former members of the IRA Army Council who claim that a five-man committee led by Adams had control of the hunger strike, keeping the Army Council in the dark about the British governments offer. He uses contemporary records to show that Thatcher had approved the offer but that Gerry Adams and the committee had replied it was 'not enough', telling the hunger strikers that 'nothing was on the table'. The prison leadership accepted the British offer, but six hunger strikers went on to die. O'Rawe asks: why? This hidden history, using contemporaneous photographs, pinpoints the key players in the drama and their responses, identifying Mountain Climber, a Derry businessman who brokered the deal, and describing the contributors to the crucial hunger strike conferences of 2008-09. O'Rawe combines a moving and courageous personal record with first-hand documentation. He provides essential background and astringent commentary on the realpolitick of the peace process and republicanism in Northern Ireland today, and its impact upon the country as a whole.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 368

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘I have the bad and disagreeable habit of writing the truth as I see it.’

IRA leader Ernie O’Malley in a letter to republican activist Sheila Humphreys, 1938

Bik McFarlane: Well, Rick?

Richard O’Rawe: I think there’s enough there, Bikso.

Bik McFarlane: I agree. I’ll write to the outside an’ let them know our thinkin’.

H-Block 3, 5 July 1981

Reporter: Who took the decision to reject that [Mountain Climber] offer?

Bik McFarlane: There was no offer of that description.

Reporter: At all?

Bik McFarlane: Whatsoever. No offer existed.

UTVNews, 28 February 2005

‘That conversation did not happen. I did not write out to the [IRA] Army Council and tell them we were accepting [a deal]. I couldn’t have. I couldn’t have accepted something that didn’t exist.’

Bik McFarlane, Irish News, 11 March 2005

‘Something was going down. And I said to Richard [O’Rawe], this is amazing, this is a huge opportunity and I feel there’s the potential here [in the Mountain Climber process] to end this.’

Bik McFarlane, Belfast Telegraph, 4 June 2009

‘I confirm what Richard said all along. He is 100 per cent correct. I’ve no doubts that he’s right in what he says.’

Gerard ‘Cleaky’ Clarke, 23 May 2009

‘I think, morally, that the leadership on the outside should have intervened [to end the hunger strike]. This is an army; we were all volunteers in this army; the leadership had direct responsibility over these men. And I think they betrayed to a large extent the comradeship that was there …

[It was] cowardly in many ways…to allow mothers and sisters and … fathers to make these decisions [to allow or not to allow their loved ones to die] … allowing that to happen was a total disregard of the responsibility that they had to these people…

I believe that was the reason why the leadership on the outside did not intervene, because of the street protests that were taking place, because of the political party that Sinn Féin was building.’

Brendan ‘The Dark’ Hughes —from Ed Moloney, Voices from the Grave (2010)

Contents

Title PageEpigraphForewordPrologueOneTwoThreeFourFiveSixSevenEightNineTenElevenTwelveThirteenFourteenFifteenSixteenSeventeenEighteenNineteenTwentyTwenty-oneTwenty-twoTwenty-threeTwenty-fourEpilogueAppendix 1Appendix 2The Second Hunger Strike: A ChronologyNotesBibliographyIndexPlatesCopyright

Foreword

THIS IS quite possibly one of the most important stories to come out of the Troubles in Northern Ireland because it helps to explain how and why they came to an end in a way that is revelatory, deeply disturbing, unprecedented and convincing. But before I explain what I mean by all that, I have a confession to make. As they say in the country where I now live, I have, or rather had, a dog in this fight. I did not want Richard O’Rawe to go down the road that has led to this book.

It was not that I did not want the story of what really happened in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh during the torrid summer of 1981 to be told. Far from it. I am a journalist very much of the ‘publish and be damned’ school, a firm believer that if you know a story to be true and important and that its publication will not result in physical harm to others, then you should do all you can to get it out to the reading, listening or viewing public. Why be a journalist otherwise?

I also believed Richard’s account from the moment I heard it. During much of the hunger strike period in 1981, I was the stand-in Northern Editor of The Irish Times and I am pleased to say that the work of the paper’s Belfast office during those awful months was in a league of its own. We broke one story after another and got closer to what was going on than any other media outlet.

As a result of what I had learned, I had become extremely sceptical of the official line from the Provos that the prisoners were in charge of the protest. The small bits and pieces of evidence that I had accumulated suggested that Gerry Adams and the people around him were really calling the shots and, by August 1981, I had come to believe that they were not interested in a settlement. It wasn’t just that the procession of coffins from the prison hospital in Long Kesh was helping to keep the pot boiling on the streets of Northern Ireland, which it was, but that I had a fair idea of what was really going on in the minds of the Provo leadership.

Long before the hunger strikes happened, I knew that there was a strong view in the group around Gerry Adams (we didn’t call it the Think Tank in those days but that is what it was) that Sinn Féin should go political, and stand for elections. But that was a dangerous argument to advocate in a movement that had split from the Official IRA largely in protest at the contaminating effect of conventional politics. The Provisionals were people for whom the gun was the purest and only acceptable expression of political belief, whereas electoral politics, as Irish history bore witness, was the pathway to reformism and compromise.

By 1979 or 1980, those around Adams would talk wistfully to me of how, in five or ten years maybe, they might be able to persuade their other colleagues to stand Sinn Féin candidates for Belfast City Council. But that was as far as their horizons were permitted to expand. Suddenly, just a couple of years later, all had changed utterly. Bobby Sands had been elected to Westminster and Kieran Doherty and Paddy Agnew returned to the Dáil. All three were IRA prisoners. Council elections in the North had in the meantime seen success for anti-H-Block candidates, especially in Belfast, and Owen Carron was poised to take Sands’ seat after his death had created a by-election.

It seemed to me that fate had dealt an extraordinary hand to the Adams camp. Suddenly they had an opportunity to fast-forward all their political ambitions in a very real way. Gone was the limited goal of winning seats to Belfast Council in the distant, uncertain future; now it was possible to get into the big game in one go and to do so in a very acceptable way to their grassroots. The dismay and even anger shown by the British and Irish establishments, along with the bulk of the media, at the electoral success of the hunger strikers had, in the eyes of IRA supporters, transformed the mundane process of seeking votes into a worthwhile revolutionary tactic.

So when Richard O’Rawe came forward with a story that strongly suggested that efforts to reach a settlement of the hunger strike in July 1981 had been thwarted by Gerry Adams and those around him, it made complete sense to me. A settlement in July would probably have cost Owen Carron the Fermanagh-South Tyrone by-election and torpedoed Sinn Féin’s ambitions to embrace electoral politics.

The key bloc in that constituency, SDLP supporters who normally reviled the IRA, had got Sands elected in order to end the hunger strike but if the protest had ended before the next by-election why on earth would they come out to vote for Carron? Keeping the hunger strike going gave them a reason to vote for Carron and hence the motive for undermining a proposed resolution. Victory in the Fermanagh-South Tyrone by-election made it easier for Sinn Féin leaders to persuade their followers to embrace electoral politics.

I had long suspected that something like this had happened and wrote words to that effect in my study of the peace process, A Secret History of the IRA. But I had always focused on events at the end of July when Gerry Adams and Owen Carron had visited the H-Blocks to talk to the hunger strikers but stopped well short of ordering them off the protest as Adams had told Fr Denis Faul he would. What I did not realize, until Richard O’Rawe told his story, was that the key moment had come earlier that month.

There was another reason why I believed his story. By 2001 I had left Ireland and was living in New York. But before I departed, I had set up an oral history archive funded by Boston College designed to collect the life stories of those who had fought in the conflict. These were stories that would be lost otherwise and which could now be safely collected, given that the Troubles were ending. The stories would stay in the archive until the interviewee’s death, after which they would be made public; at least that was the plan.

My researcher, Anthony McIntyre, himself a former IRA ‘Blanketman’, had come across Richard O’Rawe’s story and we both agreed that, if possible, he should be interviewed for the archive. That was easier said than done. As with all our interviewees, the decision to participate and how much of their life stories they wished to reveal was entirely a matter for themselves. Interviewees were never put under any pressure. It took weeks and months before Richard finally decided to sit in front of a microphone and as long before he was ready to talk about the events of early July 1981. When he did, it was, I was told, a moment of great emotion with many tears shed, as if a dam had finally burst.

This was not the behaviour of someone who had concocted a slanderous lie in order to cause problems for others but that of a person who knew the great danger he was putting himself in and who had been living with guilt over his part in these events for far too long. These were the telltale symptoms of truth. As so often in journalism, it is features of the story like these, which convince as much as checkable facts.

Then something unexpected happened. I had imagined, even hoped, that the Boston College archive would provide psychological solace for some interviewees. After all, they lived in a world where the rules of omertà applied and were enforced sometimes ruthlessly. Perhaps being allowed to tell stories that had been bottled up for too long could give relief. That was certainly the case with Richard O’Rawe but from being a reluctant interviewee he was transformed into someone who now wanted to tell the world his story, to trumpet it from the rooftops. He wanted, he announced, to write a book about what had happened.

I understood and sympathized with this but I also knew that what lay in store for him could be very unpleasant indeed. Those who had the most to lose if the story was made public had been at the top of a very greasy pole for a long time. They had stayed there because they had grown sharp claws that they never hesitated to use against critics, rivals and enemies – or indeed writers who probed too deeply into their affairs. I had some experience of this myself in my journalistic dealings with them, and my researcher Anthony McIntyre had more. Richard and his family lived in the middle of West Belfast, cheek by jowl with people who would now regard him as a traitor. They could and would make his life hell. I tried to dissuade him, to scare him even but to no avail. He had the right to tell his own story and he did.

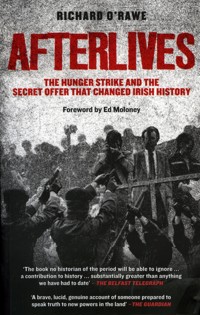

With hindsight, Blanketmen was like the first pebbles to move on a hillside populated with unstable boulders. This book, Afterlives, chronicles the avalanche that has followed, the exposed lies, the documentary evidence, the eye- or rather ear-witnesses, the persuasive testimony of participants, and so on. Taken together they provide a compelling, powerful and virtually incontestable case that in the summer of 1981 Gerry Adams and those around him thwarted a proposed settlement of the IRA/INLA hunger strikes that had been put forward by Margaret Thatcher and accepted by the prisoners’ leaders.

The rest, as they say, is history. The hunger strike made Sinn Féin’s successful excursion into electoral politics possible; the subsequent tensions between the IRA’s armed struggle and Sinn Féin’s politics produced the peace process and ultimately the end of the conflict. Had the offer of July 1981 not been undermined, it is possible, even probable, that none of this would have happened.

There will be those who will say that the end justified the means, that the achievement of peace was a pearl whose price was worth paying. That may be the case. But it is important to remember that six men died who needn’t have died and they went to their graves not knowing they could have lived. One can only wonder how peacefully rest the heads of those who sent them there.

Ed Moloney New York, October 2010

Prologue

OUTSIDE THE WINDOW on the first floor of Belfast’s Europa Hotel the flagpoles swayed precariously in the wind. Across the road, at the entrance to Robinson’s bar, a bouncer shuffled in the ear-biting chill, his bulbous form straining against a buttoned, black Crombie overcoat. To his right, outside the Housing Executive offices, stood Scots Mick, his weather-beaten face and outstretched hand appealing to passers-by. I had worked in a hostel for alcoholics and Mick had been a resident. He had been doing well then, off the booze for over two years, but by the looks of his tomato face he was back on the sauce. He called it ‘work’, scrounging money off people, and he was good at it.

That was in January 2005, and a BBC journalist and I had arranged to meet to discuss a possible documentary on my forthcoming book Blanketmen: An Untold Story of the H-Block Hunger Strike. The journalist was concerned that I was aware of what lay before me. ‘Believe me, Ricky,’ he said, ‘come publication day, you’d better have the hatches battened down ’cause you’re gonna be right smack in the way of the perfect storm.’1 I understood that, or at least thought I did.

As a seventeen-year-old student, I had graduated from the revolutionary class of 1971 with a degree in idealism, and then pursued a career in the IRA. Now, thirty-four years later, having been public relations officer for the protesting prisoners in the H-Blocks with a front-seat view of the unfolding drama inside the prison, I was lifting the veil on the 1981 IRA/INLA hunger strike, during which ten of my prison comrades and cherished friends had died under horrendous circumstances. I was convinced that the last six hunger strikers need not have lost their lives, because the British government, through an intermediary codenamed ‘Mountain Climber’, had made a substantial offer of settlement on 5 July 1981, before the fifth hunger striker, Joe McDonnell had died. That offer had been accepted by the IRA prison leadership, but rejected by the outside IRA leadership. This rejection came into the jail in a communication ‘comm’ from Gerry Adams, who said that the outside leadership was ‘surprised’ that we had accepted the offer, and that ‘More is needed.’2 During the hunger strike Adams headed a steering committee of senior republicans, whose remit was to co-ordinate publicity on the outside, and to liaise with the prisoners on all matters relating to the hunger strike. Throughout this book, I will refer to this body simply as the ‘committee’.

I knew that my claims were incendiary. I recognized that by exhuming this particular past, certain republican leaders would bare their teeth. These men, as in 1981, were powerful: they had the authority to bring down on my shoulders the full weight of the republican movement. I expected the poison quills to be sharpened. I knew a chorus of orchestrated indignation and abuse, followed inevitably by character assassination and ostracism, would ensue. An on-side former hunger striker or two would be put on stand-by to lend weight to the campaign. I could almost hear them say: ‘He can’t argue with an ex-hunger striker.’ I could, and I would.

Things became serious when a former Blanketman, reputed to be the then adjutant-general of the IRA, visited my home on 17 July 2003. This man did not threaten me, and he emphasized that he was not there to ‘gag’ me. He said that he was speaking on behalf of the ‘leadership’ and enquired if I was writing a book about the hunger strike.

I told him that I was.

Was I writing anything that might hurt Gerry Adams?

I was ‘not in the business of hurting anyone’.

What exactly was I writing?

The truth about the hunger strike.

Was I going to say that the 1981 leadership sacrificed the hunger strikers?

No.

Would I speak to Gerry Adams?

No: I would not agree to the book being ‘sanitized’, and I would not pull out of writing it.

He said that no one was asking me to sanitize or pull it.

It was my turn to become inquisitor.

Did he know what had happened in the prison?

‘Most of it.’

Did he know that the prison leadership had accepted the Mountain Climber offer?

‘Bad things happen in war, Ricky.’

That gruesome riposte and sidestep was unexpected. The inquisition was over. I made an excuse and we parted as friends.

This encounter told me that Adams and the leadership were fully aware that I was writing a book about the 1981 hunger strike. Yet surprisingly their initial response to Blanketmen was one of confusion and contradiction. They would soon recover their composure.

What is undisputable about the 1981 hunger strike is that the last six hunger strikers died in tragic and obscure circumstances. Despite this, and the numerous books written on the subject, we have yet to understand what really happened in the negotiations between the committee and the British government.

The British penchant for secrecy is legendary, and for four years it was my word versus the committee’s. Then came a breakthrough. Thanks to a change in the law designed to open up more government secrets to scrutiny, a prominent journalist was given extracts of July 1981 letters from 10 Downing Street to the Northern Ireland Office, in March 2009. The content of these letters reveals that Margaret Thatcher had been closely monitoring the contacts between her intelligence officers and senior republicans Gerry Adams and Danny Morrison. They demonstrate that she had personally authorized significant prison concessions to the prisoners, which were passed on to the Provisional IRA, or at least that was what the British believed. These papers divulge that the Mountain Climber offer had been rejected by the republican negotiators, even though we in the prison leadership had accepted it. These letters will be examined and analysed in this narrative.

The Mountain Climber himself, businessman Brendan Duddy, gave candid and revealing testimony at a hunger strike conference in his native Derry in May 2009. With an audience of over three hundred hanging on his every word, Duddy verified the authenticity of a British statement he had passed on to the IRA leadership on 5 July 1981. That statement, from the then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Humphrey Atkins, listed the changes that would be implemented in the prison as soon as the hunger strike ended. The Mountain Climber also confirmed that the IRA negotiators had rejected the offer.

To date, the man in charge of the special hunger-strike committee, Gerry Adams, has had little of substance to say by way of self-defence about his role in the hunger strike, preferring to let others do that for him. Neither had the committee released their papers and comms about the clandestine talks since Blanketmen was published in 2005. Had they nothing to hide, they would have mounted a defence and welcomed a forensic examination of their position, but they chose not to do so.

In Afterlives I shall be examining the contradictory and incriminating public stances taken by the committee and their acolytes since Blanketmen was published. Evidence will be presented to show that the authority of the IRA Army Council had been usurped by the committee, and that the ruling body of the republican movement had never been made aware of British government contacts, much less the offer that Margaret Thatcher had made to end the hunger strike. Naturally, we Blanketmen assumed that our Army Council had its finger on the pulse. It hadn’t. Only after the book came out did I learn that the committee had surreptitiously arrogated the Council’s authority. As a result, when I wrote Blanketmen I mistakenly maligned Army Council members who knew nothing of this episode and who had played no part in it. To these Army Council members, I offer sincere apologies.

It has also become clear that the committee excluded the IRA’s junior partners in the hunger strike, the INLA, from the secret discussions with the British, even though three INLA volunteers died on the fast, with the last two being among the last six hunger stikers to die. A spokesperson for the INLA Army Council of 1981 will substantiate that the last two INLA hunger strikers to die, Kevin Lynch and Micky Devine, went to their deaths not knowing that an honourable ending to the hunger strike had been on offer from 5 July 1981 – over four and six weeks respectively before each man passed away.

Two surviving hunger strikers, one from the IRA, the other from the INLA, will confirm that they were never told of any offer when they were on the fast, while another who was hostile to my position, will inadvertently do likewise.

Two further fellow Blanketmen on the leadership wing in the H-Blocks will verify that they had overheard a conversation between Bik McFarlane and myself, during which we accepted the Mountain Climber offer. One is happy to allow his name to be published; the other prefers to remain anonymous, although he has confirmed my account to some of the hunger-striker families.

A representative from the Irish Commission for Justice and Peace (ICJP) will interpret that body’s efforts to settle the hunger strike honourably. He will also confirm that the offer the ICJP believed it had secured from the British (before Joe McDonnell’s death) was, in every detail, the twin of the offer the British secretly made to the IRA Army Council.

It is now generally accepted that the seed of the Northern Ireland peace process was planted in the prison protests over political status, and was watered by the deaths of the ten H-Block hunger strikers. This was a deeply ironic consequence of the prison sacrifices. Bobby Sands and our nine comrades believed that their actions would advance the cause of socialism in the context of a united Ireland. What emerged was something the IRA had always rejected – an internal ‘Northern Ireland’ settlement. However, that is not my concern in this book. What is my concern is getting to the bottom of the hunger-strike story.

It has been suggested that the committee was responsible for the biggest cover-up and scandal in the history of Irish republicanism. Others believe that the committee, inexperienced in negotiations, made critical errors of judgment. The problem with both scenarios is that no committee member has ever accepted responsibility for any decision connected to the hunger strike. Where lies the truth? This narrative will go some way towards answering that question.

Richard O’RaweOctober 2010

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

The title of this book was inspired by Derek Mahon’s poem ‘Afterlives’ from The Snow Party (Oxford University Press, 1975).

NOTES

1. Conversation with member of the BBCSpotlight documentary team.

2. Communication (comm) from Gerry Adams to prison leadership, 6 July 1981.

One

SUPPOSE SOMEONE told you to keep your mouth shut or you could be shot: what would you do? When that happened to me in 1991 I zipped it. In taking this course of least resistance, I felt lousy; it was as if I had betrayed the ten hunger strikers who had laid down their lives for me and for the rest of the Blanketmen in 1981. But I always knew that some day I would find the courage to recount their story.

That day came when my book Blanketmen:An Untold Story of the H-Block Hunger Strike was released. It was my account of what happened at leadership level in the H-Blocks of The Maze/Long Kesh prison during the 1981 hunger strike.

From the minute the book hit the shelves, it was fiercely slated by some members of the 1981 IRA leadership. Besides the few individuals who knew what they were talking about, there were other republicans who professed to ‘know’ things, or to speak ‘with authority’ about the hunger strike – people whom I had never met in my life. It did not matter. What did matter was putting my dead comrades’ story to right. If some people were upset, then so be it – the leadership had floated along on a raft of deceit for far too long.

Tellingly, Gerry Adams, the man at the helm, shunned debate. His self-imposed press exile ensured that he could not be quoted or challenged. Besides the tactical advantages of sending others in to bat for him on the hunger strike issue, Adams was preoccupied with other problems in that winter of political isolation, not least the fallout from the Northern Bank raid in Belfast, during which £26 million was stolen.

Although the IRA denied involvement in the robbery, few people believed them. The Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland, Sir Hugh Orde, made it clear that the IRA had been responsible. Most people accepted that no other paramilitary body would have had the expertise to carry off such a complex operation.

On the RTÉ current affairs programme This Week, Taoiseach Bertie Ahern pulled no punches: ‘This was an IRA job, a Provisional IRA job, which would have been known to the provisional leadership.’1

Before the robbery, negotiations between the Reverend Ian Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Féin, the political wing of the republican movement, had reached a delicate stage. Paisley, the roaring, granite-like voice of extreme unionism, was demanding to be shown photographs of the IRA’s weapons being destroyed before he would go into government with Sinn Féin.

At stake was an entente cordiale, an agreement that, if achievable, could end centuries of nationalist and unionist conflict. The bank robbery dampened any enthusiasm within DUP ranks for such an accord.

While this robbery had all the appearances of an act of reckless self-harm, political commentators of note looked around for reasons why the IRA would jeopardize a 24-year peace strategy. Three answers emerged: the first was that the robbery had been an attempt by dissenting elements within the IRA to scupper the peace process. This was an unlikely scenario because by the end of 2004 opposition to the Adams/McGuinness-led peace agenda within the IRA had been obliterated. The second was that the Dublin and London governments had previously ignored intelligence reports that the IRA had carried out other large-scale robberies in the months before the Northern Bank heist, and it was assumed that they would do so again. That possibility could not be so easily dismissed. The third answer was that the robbery had been approved by leading republican politicos so they could finally free themselves from the IRA’s straitjacket. The thinking behind this premise was that there would be, inevitably, a profound sense of outrage at the robbery, forcing the IRA to self-destruct – which was what eventually happened.

These theories are unproven because the IRA has said that none of its members had any involvement in the robbery, and to date no IRA member has been convicted for it.

If the IRA had planned and carried out the Northern Bank robbery, they certainly did not plan the horrific murder of 33-year-old Robert McCartney, although it was alleged that their members had carried it out.

Robert McCartney lived in the nationalist Short Strand area of Belfast, along with his partner, Bridgeen, and their two young sons, Conlaed and Brandon. On the evening of 30 January 2005 Robert and some friends got involved in a fight with local republicans in Magennis’s bar in the Markets area. The fight ended up outside the bar, where Robert was knifed. He died of his wounds the next day at 8.10 am. His friend, Brendan Devine, was also stabbed and seriously injured.

It was a savage murder, made worse by the revelation that, as soon as the crime occurred, an IRA volunteer apparently announced to the seventy-strong pub patrons, mostly republicans back from the annual Bloody Sunday demonstration: ‘This is IRA business. Nobody saw anything.’2 A forensic clean-up was then carried out, and the bar’s CCTV tape was confiscated and destroyed.

Robert’s partner and his five sisters tirelessly fought for ‘Justice for Robert’. Their protracted campaign garnered support from the European Parliament, the United States Congress and Senate, and President George W. Bush, among others, but it led to no arrests.

The Northern Bank robbery and the murder of Robert McCartney convinced people that the political journey, which had begun with the election of Bobby Sands in 1981, had ground to a halt. It must have seemed so, even to the indefatigable Gerry Adams. And who would have blamed Adams, who many believed to be the primary architect of the peace process, if he had handed over the reins of power to someone else and simply walked away? Had he done so, Adams might have found an opportunity to look back and reflect on the life and times of his old friend, the revolutionary Bobby Sands, and on the aftermath of the prison leader’s election to Westminster in the Fermanagh-South Tyrone constituency in June 1981.

Bobby Sands had been a disciple of Gerry Adams, one of the Big Lad’s Cage 11 golden boys in the days before the H-Blocks were occupied, when republican prisoners did their time in the compounds, or ‘cages’, of Long Kesh in the 1970s. It was in Cage 11 that the charismatic Adams, and Brendan ‘The Dark’ Hughes, preached radical left-wing politics to other prisoners, many of them fresh-faced young republicans. Among those smitten with revolutionary zeal were Bobby Sands, Bik McFarlane and Seanna Walsh. These men, along with Hughes, would become future OCs of the H-Block prisoners.

Of Bobby’s election to the Fermanagh-South Tyrone seat, Adams said in 1996: ‘I pondered with a certain wry satisfaction the comparison between my first electoral experience, folding leaflets for Liam McMillen in 1964 and suffering lost deposits, and the tremendous impact of Bobby’s election.’3 Some commentators have said that when Bobby died on hunger strike on 5 May 1981, Adams was still pondering, musing whether or not this was the break he had been waiting for to end the IRA’s armed struggle and to stride out on the path to constitutional politics.

The election of Bobby’s replacement, Owen Carron, occurred on 20 August 1981. On that day Micky Devine became the tenth and last hunger striker to die. On 3 October 1981, on Adams’s ‘advice’, the hunger strike ended.

Within weeks, at the annual Sinn Féin Ard Fheis, the party adopted the ‘Ballot box and Armalite’ strategy (so called by Danny Morrison) and agreed to contest elections in both jurisdictions of Ireland. In that motion, the first momentous step was formally taken on the road to constitutional politics and the compromises that would inevitably follow. Blinded by the light of Sands’ and Carron’s electoral success, not many of the delegates who voted for the fresh approach would have realized that they had just slipped the black spot to the IRA.

A year later, three members of the committee, Gerry Adams, Danny Morrison and Martin McGuinness, were elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly, with Sinn Féin gaining over 10 per cent of the popular vote.

Adams’s stature as a brilliant tactician grew when, in June 1983, he captured the West Belfast Westminster seat from independent candidate Gerry Fitt, former leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party. As well as that, Sinn Féin garnered 102,701 votes in the North of Ireland. For many, Adams was the dynamic genius behind the new age of republican enlightenment; he had promised change, and he was manifestly delivering. Suddenly Sinn Féin, the old chestnut of constitutional Northern politics, could no longer be regarded as a joke. Party offices were opened in every nationalist district, and activists, many of them former IRA prisoners, fine-tuned their radicalism to the task of solving the everyday problems of the people. This was Sands’s socialism made flesh – and it had all the appearances of a rolling revolution.

It was small wonder, then, that Adams consolidated his power base within the republican movement when Ruairí Ó Brádaigh resigned as president of Sinn Féin in November 1983. Since then historians have portrayed Adams’s accession to the presidency as the death knell of 1940s’ and 1950s’ republicanism. Perhaps, but Adams’s coup d’état, which had profited enormously from the death of the hunger strikers, was completed only when the then IRA Chief-of-Staff and hard-line socialist, Army Council member Ivor Bell, left the IRA. Bell had been seventeen years old when he was interned during the IRA’s 1950s campaign. After the civil rights campaign of 1969, he became a leading figure of the ProvisionalIRA.

The battle for hegemony between Adams and Bell, former close friends and comrades-in-arms, bore few of the similarities to that which Adams had fought with Ruairí Ó Bradáigh and the traditionalists. There was no democratic vote on Bell’s future role in the republican movement. According to Ed Moloney in his book A Secret History of theIRA, Bell was charged with ‘treachery’ and court-martialled. Found guilty, he faced a death sentence, but this was commuted on the advice of Gerry Adams, on condition that Bell remained silent about these events for the rest of his life. To this day he has never broken that silence.

From 1983 until the IRA ceasefire in 1994, Adams and McGuinness led a relentless, often clandestine, drive towards a peace accord with the British.

From the outset the British made it clear that the core republican objective of a British withdrawal from Ireland was not negotiable and that there could not be a united Ireland unless it was voted for by the majority of the citizens in Northern Ireland. In effect the British were reinforcing the unionist veto – the real reason why the war had started. The new republican leadership offered little resistance to this fundamental position.

After internal IRA dissension, the ceasefire broke down in February 1996, but was restored in July 1997. Following the reintroduction of the ceasefire, an IRA Convention narrowly backed the Adams peace strategy.

In 1997 Sinn Féin accepted the Mitchell Principles, the tenets of which committed the republican movement and all the other political parties to ‘democratic and exclusively peaceful means of resolving issues’, and to ‘renounce for themselves, and to oppose any efforts by others, to use force, or threaten to use force, to influence the course or the outcome of all-party negotiations’. This was a public declaration by the republican movement that only peaceful means should be used to pursue political power. It was, de facto, an acknowledgment that the armed struggle was over. The signing of the Good Friday Agreement followed in April 1998.

The overthrow of the moderate Ulster Unionist Party by the Democratic Unionist Party in the Northern Ireland Assembly elections of May 2003 led to a hardening of the unionist position, and threatened the collapse of the hard-fought-for peace process. Even before the Northern Bank robbery and the murder of Robert McCartney, the Revd Ian Paisley had said: ‘The IRA needs to be humiliated. And they need to wear their sackcloth and ashes, not in a backroom, but openly.’4

So if Adams did find time in 2004–5 to look back and reflect, the Sinn Féin president would have seen that he had piloted the republican movement from one side of a political universe to another. Behind him were the days of inviolable republican principle, when Northern Ireland was regarded as an illegal ‘statelet’ that needed not to be reformed but to be dismantled – by any means. Gone also was the IRA’s armed struggle, and those former comrades who still supported its tactical use. Sands’s dream of a socialist republic had all but been jettisoned too in the rush to conformity and legitimacy. Had Adams had time to catch his breath in that desolate autumn of 2005, he would surely have wearied of his sorrows and woes.

There was, however, another woe in the wind – Blanketmen. In the weeks before the book was to be launched, I had some very difficult decisions to make. My most pressing dilemma was whether or not to inform the families of the dead hunger strikers about the book’s contents; if I didn’t, I would be exposed to the criticism of being indifferent to, even disrespectful of, their feelings and the memory of their dead relatives. Nothing could have been further from the truth. I wrote the book in good conscience because not only had their loved ones been like brothers to me, but I believed that I had a sacred duty to right a terrible wrong: the untimely and unnecessary deaths of the last six hunger strikers.

There were dangers in disclosure. Undoubtedly the families would have wanted to read the book before giving an opinion. Some family members were Sinn Féin supporters; at least one was a Sinn Féin elected representative. What if, armed with a critical exposé, the republican leaders whom I had criticized convinced even some of the families to oppose the publication of the book at a highly emotive press conference?

(In June 2009, four years after the publication of Blanketmen, the same leading republicans gathered representatives from eight families together in a hall in Gulladuff, County Derry, and afterwards persuaded some family members to sign a statement calling on me and others to stop probing into the hunger strike.)

After weighing everything up, I decided against telling the families.

I had another thorny choice to make. The BBC had initially agreed to film a hunger-strike documentary to coincide with the book’s release. For reasons never made clear, the BBC sought to change the initial agreement I had with them. This was unacceptable and I withdrew from the project, suspecting that the BBC controllers were concerned about the possible effect the programme might have on the peace process.

NOTES

1. An Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, RTÉ programme, This Week, 9 January 2005.

2. Catherine McCartney, Walls of Silence (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan Ltd 2007), p. 10.

3. Gerry Adams, Before the Dawn: An Autobiography (London: Heinemann 1996), p. 294.

4. Revd Ian Paisley in a speech in Ballymena, 7 November 2007.

Two

BLANKETMEN: An Untold Story of the H-Block Hunger Strike was published on 28 February 2005. Most of the book dealt with my experiences of the blanket protest and the rich assortment of characters I met in the wings of H3 and H6. A spontaneous rather than a planned act of defiance, the blanket protest began in 1977 when the British government tried to criminalize the republican armed struggle by forcing IRA and INLA prisoners to wear prison/criminal uniforms and to conform to prison rules.

The first IRA volunteer to refuse to wear the ‘monkey suit’ was Kieran ‘Header’ Nugent. He told the screws when they tried to force him to wear the monkey suit, ‘You’ll have to nail it to my back.’ Seeing his strength of character, the screws gave Nugent a blanket to wear. By that act, the blanket protest was born. Hundreds of other determined and committed republicans soon followed Nugent’s example.

In a four-year period a bitter war of attrition was fought out in the H-Blocks. At the start of the protest the Blanketmen were locked in their cells for twenty-four hours a day and denied access to everything except food and water, a monthly visit, and a weekly letter. That did not break our spirits, so the British government, through its prison warders, launched a vicious campaign of brutality against us. Men were beaten, and some had their testicles squeezed until they lost consciousness. We initiated a no-wash protest, and for three years we not only refused to wash, but smeared our excrement on the walls of our cells.

Hunger strike ensued.

The first hunger strike ended in December 1980 without loss of life. Unfortunately, it failed to win any of our major demands. That negative result all but ensured a second hunger strike.

The IRA prison Officer Commanding (OC), Bobby Sands, led the second hunger strike, which started when he refused food on 1 March 1981. Sands and nine other republicans were to die on the fast.

Once a prisoner went on hunger strike, he relinquished his rank, and when Bobby refused food his Public Relations Officer, Bik McFarlane, took over from him, becoming prison OC. I was then chosen by Bobby and Bik to take over as PRO. By virtue of this appointment, I became Bik’s closest confidante in the prison, and from then until the end of the hunger strike, we were in constant contact on most matters relating to the fast. Therefore I was in a unique position to know what occurred inside the prison leadership during the hunger strike – very different from the version of events that some republican leaders on the outside had put out in the years since it ended. So I wrote Blanketmen. In it I asserted:

That, rather than the Sinn Féin version of events that it was the prisoners who controlled the hunger strike, it had, in fact, been the IRA Army Council that had had unrestricted control, and that, for us prisoners, the Army Council was the umbrella under which all the other contentious issues sheltered.The British government had made a substantial offer to settle the hunger strike following the release of a conciliatory statement I had written on behalf of the prisoners on 4 July 1981. This offer, sometimes known as the ‘Mountain Climber’ offer, was presented on at least two different occasions to Gerry Adams and Danny Morrison by mediators from Derry, who had been in contact with British government representatives. The first occasion had been shortly before the fifth hunger striker, Joe McDonnell, died on 8 July 1981, and the second was after the sixth hunger striker, Martin Hurson, died on 13 July.The then Sinn Féin national director of publicity, Danny Morrison, told Bik McFarlane the details of the offer when they met in the prison hospital on 5 July. Morrison has said, since the book’s publication, that he had also made the hunger strikers aware of the offer.When McFarlane returned to our wing, he wrote me out a message outlining what was on offer. Subsequently he and I had accepted it, believing there was enough in it to end the hunger strike with honour.Our agreement to accept the offer was shouted in Irish out of our cell windows, and during our brief tête-à-tête McFarlane said he would write to the outside leadership and let them know of our approval.Shortly after McFarlane had communicated our acceptance to the outside leadership, a comm from Gerry Adams arrived into the prison informing us that there was not enough in the offer to settle the hunger strike, and that ‘more was needed’.McFarlane and I accepted what we believed to have been the position of the IRA Army Council.Adams’s comm rejecting the offer ensured the prolongation of the hunger strike, with six more hunger strikers dying in its wake.I suggested that there were only two possible explanations as to why the IRA Army Council would reject our