23,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

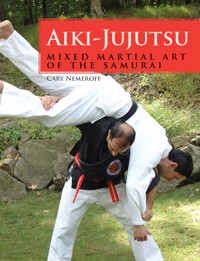

Aiki-Jujutsu: Mixed Martial Art of the Samurai is essential reading for practitioners and instructors of mixed martial arts, the traditional Asian martial arts and those who seek to learn more about the techniques, philosophy and history of the fighting arts of the Samurai. Using easy to follow, step-by-step photography and text, 10th Dan Cary Nemeroff demonstrates how to perform the throws, hand strikes, grappling/groundwork manoeuvres, blocks, break-falls, kicks and sword-disarming techniques of the complete Aiki-Jujutsu system, including Kempo-Jutsu, Aiki-Jutsu and Ju-Jutsu. It also provides a concise history of the concepts and systems surrounding Aiki-Jujutsu's development, such as Budo and Bujutsu, enabling the practitioner to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the art.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 209

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

AIKI-JUJUTSU

MIXED MARTIAL ART OF THE SAMURAI

CARY NEMEROFF

Copyright

First published in 2013 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2013

© Cary Nemeroff 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 570 6

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Author’s Biography

Foreword

Acknowledgements

PART I – Martial History

1 Bujutsu: Martial Arts

Ryu: Style or System ‘School of Thought’

The Individual Martial Arts Disciplines

Kempo-Jutsu

Aiki-Jujutsu: Second Method of Defence

Aiki-Jutsu

Ju-Jutsu: Soft, Subtle, Economical

2 Budo: Martial Ways

Aikido

Judo: Gentle Way

More About Budo

PART II – Kempo-Jutsu

3 Fukasa-Ryu Kempo-Jutsu

Blocking Strategy

Posture and State of Mind

Dachi Waza: Stances

Atemi Waza: Hand Striking Techniques

Geri Waza: Kicking Techniques

Striking Strategy

Uke Waza: Blocking Techniques

Evasive and Invasive Techniques Against the Sword

PART III – Aiki-Jujutsu: Body-conditioning Techniques

4 Ukemi Waza: Break-Falling Techniques

Ushiro Ukemi: Rear Break-Fall

Yoko Ukemi: Side Break-Fall

Mae Chugaeri: Front Somersault Break-Fall

Yoko Chugaeri: Side Somersault Break-Fall

Mae Ukemi: Front Break-Fall

An After-Thought Regarding Ukemi

5 Rotary Rolls, Knee Walking and Body Pivots

Mae Zempo Kaiten: Front Rotary Roll

Ushiro Zempo Kaiten: Rear Rotary Roll

Shikko Waza: Knee-Walking Techniques

Tai Sabaki: Body Pivots

PART IV – Fukasa-Ryu Aiki-Jujutsu

6 Aiki Nage Waza: Throwing Techniques from Samurai Sword and Weapons-Free Attacks

Aiki Sei Otoshi: Shoulder Drop

Shomen-Uchi, Aiki Sei Otoshi: Shoulder Drop from a Vertical ‘Head Cut’ Samurai Sword Attack

Aiki Tai Otoshi: Body Drop

Gyaku Age Uchi, Aiki Tai Otoshi: Reverse Rising Cut to Body Drop

Aiki Soto Tekubi Nage: Outer Wrist Throw

Nuki Dashi, Soto Tekubi Nage: Outer Wrist Throw from Sword Draw

Aiki Kote Gaeshi: Minor Wrist Overturn

Nuki Dashi, Aiki Kote Gaeshi: Minor Wrist Overturn Against a Sword Draw

Aiki Morote Seio Nage: Two-Handed Shoulder Throw

Shomen-Uchi, Aiki Morote Seio Nage: Two-Handed Shoulder Throw from a Vertical ‘Head Cut’ Samurai Sword Attack

Aiki Ura Shiho Nage: Circular Four Winds Throw

Shomen-Uchi, Aiki Ura Shiho Nage: Circular Four Winds Throw from a Vertical ‘Head Cut’ Samurai Sword Attack

Aiki Ashi Kaiten Nage: Leg Rotary Throw

Shomen-Uchi, Aiki Ashi Kaiten Nage: Leg Rotary Throw from a Vertical ‘Head Cut’ Samurai Sword Attack

Aiki Ude Kaiten Nage: Arm Rotary Throw

7 Ju-Jutsu Nage Waza: Hip Throws and Sweeps

Ippon Seio Nage: One-Arm Shoulder Throw

Koshi Guruma: Hip Wheel

O Soto Gari: Major Outer Clip

Uki Goshi: Minor Hip Throw

Tomoe Nage: Stomach Throw

Harai Goshi: Sweeping Loin Throw

Uchi Mata: Inner Thigh Throw

Hane Goshi: Spring Hip Throw

Tsuri Komi Goshi: Lift Pull Hip Throw

Sode Tsuri Komi Goshi: Sleeve Lift Pull Hip Throw

8 Katame Waza: Groundwork ‘Holding’ Techniques

Kesa Gatame: Scarf Hold

Kata Gatame: Shoulder Hold

Ude Osae Jime: Arm Press Choke

Gyaku Juji Jime: Reverse Cross Choke

Kataha Gatame: Single Wing Lock

Ude Gatame: Arm-Lock

Ude Garami: Arm Entanglement

Ude Hishigi Juji Gatame: Cross Arm-Lock

GLOSSARY

INDEX

AUTHOR’S BIOGRAPHY

Cary Nemeroff, author of Mastering the Samurai Sword (Singapore: Tuttle Publishing, 2008), is a teacher of the Okinawan and Japanese martial arts, who has merged his interests in education, individuals with disabilities and the Asian combat arts into a full-time career. He has earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in Philosophy from New York University, as well as a Master of Arts degree in Education from Teachers College, Columbia University, New York.

Cary’s martial arts training began as a young boy in 1977 under the auspices of Juko-Kai International, a martial arts organization accredited in both Okinawa and the mainland of Japan. As an adolescent, his passion and skills as a martial artist grew and he ultimately became the personal student of Dr Rod Sacharnoski, President of Juko-Kai International. This relationship continues to this day. Cary has earned a 10th Degree Black Belt in Aiki-Jujutsu (Jujutsu), as well as a 9th Degree Black Belt in a variety of other Okinawan and Japanese martial arts.

Cary is founder and president of Fukasa-Ryu Bujutsu Kai, a martial arts organization that is a member of the International Okinawan Martial Arts Union and is accredited and sponsored by the Zen Kokusai Soke Budo/Bugei Renmei.

At present, Cary conducts an extensive programme of group classes for adults and children at the JCC in Manhattan, a state-of-the-art fitness and cultural facility located on the Upper West Side of New York City. Cary is fluent in sign language and conducts specialized classes for children and adults with physical and cognitive challenges, including autism and cerebral palsy. Among the martial arts he teaches are Aiki-Jujutsu, the Samurai sword (Iai-Jutsu and Ken-Jutsu), Karate and Toide (Okinawan throwing and grappling). At other venues, such as United Cerebral Palsy of NYC, he designs customized programmes and provides staff training, individual instruction and conducts clinics for schools affiliated with his own organization.

Cary Nemeroff can be reached through the Fukasa Kai website (www.fukasakai.com).

FOREWORD

Aiki-Jujutsu is the art of the Bushi, leaders of the class of Japanese warriors known as the Samurai. It was originally developed as a method to overcome sword-wielding assailants on the battlefield and, like most Japanese arts, it developed into an outstanding form of self-defence that could be utilized in modern times. I have been involved in the Japanese Jujutsu arts most of my life and have studied the Bushi warrior skill at its highest level.

Aiki is the skill to harmonize with an attacker in order to overcome one’s difference in size, strength or fighting ability. When people can actually ‘Aiki’ their opponents, they can neutralize and overcome them. Many of the traditional Japanese styles have developed the concept of Aiki to an incredible level. Having studied several of these martial styles, I have developed my own form of Juko-Ryu Aiki-Jujutsu, which preserves these powerful techniques for modern-day combat and self-defence.

Cary Nemeroff has been my student for more than thirty-five years. I am pleased to recommend his book on Aiki-Jujutsu to those who are interested in the traditional martial arts of Japan. Aiki-Jujutsu is one of the most magnificent martial arts that came from the Japanese tradition. Anyone interested in traditional training with a strong self-defence component will find this book interesting and instructive.

Rod Sacharnoski, Soke, 10th Dan

Headmaster, Juko-Ryu Bujutsu-Kai

9th Dan Hanshi, Seidokan Okinawa

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to acknowledge all of the people who helped bring this text to completion. First and foremost, I want to thank my mother, Sandy Nemeroff, for her role in editing the text in the manuscript. Her words helped the conversion of martial arts techniques into meaningful language.

I thank both of my parents for enrolling me in the martial arts as a young boy. Their persistence and constant encouragement throughout my life continue to give me the confidence to pursue my dreams.

I am grateful for my wife Tsen-Ting, my partner in life, who understands and appreciates the lifestyle that I live, which is inextricably connected to the commitment that I have to the martial arts.

I would like to honour my teacher, Rod Sacharnoski, Soke, who continues to inspire me through his philosophy and mastery of martial arts techniques. It is his generosity, trust and patience that has sculpted me into the martial artist that I am today. I am honoured that he would, once again, write the Foreword for my book.

Many thanks to all the devoted students who contributed through the photographs in the book: David Nemeroff, Dai-Shihan; Kevin Ng, Shihan; Greg Zenon, Shihan-Dai; Nicolas Fulton, Shihan-Dai; Anthony Cabrera, Sensei; Ittai Korin, Sensei; David Schnier, Sensei; Bret Koppin, Sensei; Peter Lawson, Sensei; Anita V. Stockett, Sensei; Fred Bennett, Sensei; Frantz Cochy and Wade Bailey. I am honoured by and grateful for their belief in me and my teachings, as well as their demonstration of diligence and commitment to what I do.

To Greg Zenon, Shihan-Dai, the ‘Fukasa-Kai Photographer’ who photographed 99 per cent of the fabulous pictures in this publication, I want to share my special thanks for all of his photographic contributions during the last fifteen years as a member of Fukasa-Kai.

To David Nemeroff, Dai-Shihan, who photographed the cover picture for this publication, I want to share my deepest thanks for all of his hard work and support to help Fukasa-Kai evolve to where it is today.

I wish to thank all of my devoted students. Without them, my life would be far less satisfying.

PART I

MARTIAL HISTORY

The traditional martial arts of Japan have survived the test of time. Martial history provides us with evidence that Bujutsu (the Japanese martial arts) proliferated and evolved over generations within the small families of Samurai who, beginning in Japan’s Heian period (794–1185CE), served both their Daimyo (regional lords) and ultimately the emperor and/or Shogun (military leader). Martial arts techniques were tested on the battlefields, where soldiers collided in cavalry battles as foot soldiers en masse and in individual bouts. A Samurai’s brazenness and martial aptitude were tested, resulting in either the death of one of the combatants or Seppuku (ritual suicide to preserve one’s honour).

CHAPTER 1

BUJUTSU: MARTIAL ARTS

The knowledge that a Samurai derived, and reflected upon, from his experiences in battle enabled him to formulate a methodology and breadth of technique. This ‘system’ or Ryu represented a unique school of thought or style. A Ryu would typically be taught or ‘passed down’ to the progeny of the Samurai, who would serve Japan later in life.

The Samurai, who devoted their lives to serving their country, trained in and developed a full spectrum of martial arts techniques that were effective in many different battle contexts. This complete fighting system would have been practised with the objective of perfecting the Samurai’s techniques. A period of reflection subsequent to combat could have led to the inclusion of additional forms.

Power changed hands fairly rapidly throughout the history of Japan. The country endured chaotic periods of warfare and disharmony as emperors attempted to exercise authority, while clans of militants usurped power and control of Japan’s resources. This reality led to the proliferation of ‘battle-ready’ Samurai poised for imminent engagement.

The beginning of the seventeenth century marked a noticeable change, as Japan became stable for approximately 250 years under the leadership of the Tokugawa Family (Edo period: 1603–1868CE). The small island of Okinawa represented the only significant conquest for territorial expansion during this era. Its annexation was a successful, swift operation, occurring just subsequent to the beginning of the Tokugawas’ reign. In Japan, this period of ‘relative’ peace drastically changed the day-to-day duties of the previously warring Samurai to more of a policing role, the purpose of which was to uphold order and execute the wishes of the Tokugawas. This circumstance represented an important turning point in the evolution of the Samurai martial arts; it was a time of profound reflection and martial arts practice outside the context of battlefield warfare. In this new era, a Samurai would have been more likely to have found himself involved in a one-on-one bout in plain clothes, as opposed to the typical armour worn by a field soldier. Such a change had a major impact upon how martial arts techniques could be used; for example, a Samurai confronted by an adversary wearing armour would have been limited to using striking techniques that could penetrate only the open areas in the opponent’s armour. These vulnerable areas, usually located around the joints of the body, were under-protected to allow for unobstructed movement. Faced with an ‘armour-free’ opponent, however, a Samurai could have been virtually limitless in his ability to strike any part of his opponent’s body. Furthermore, if the Samurai himself were wearing plain clothing, the rigid layers of armour that could have otherwise hampered his ability to protect himself would no longer be an issue, as he would now be able to move his body freely, without the obstruction caused by rigid armour. The Samurai arts evolved further through the integration of the wisdom acquired by the forefathers of past generations, ‘the battlefield warriors’, into a more holistic lifestyle consisting of reflection, enlightenment via rigorous training, meditation and the occasional bout that enabled the Samurai to carry out his duty to Japan and to obtain martial acuity and experience through real confrontation.

Soon after the fall of the Tokugawa Dynasty, Emperor Meiji allowed for the set-up of a government comprised of a council of Japanese officials, who would decide on laws that would be enforced by police-like figures. In 1876, the Samurai, who typically served in this capacity, were stripped of this honour and their privilege to carry a Katana (a long Samurai sword) in public. The new decrees ended a tradition that would survive on in small families of Samurai who perceived the value of the Samurai lifestyle to be its balance between physical prowess and spiritual enlightenment. Contemporary life brought about great change to the martial arts of the Samurai. There were, however, individuals who made a valiant effort to preserve and protect the Koryu, the ancient martial arts of the Samurai, so the lessons acquired from real combat would not face extinction.

Ryu: Style or System ‘School of Thought’

The Meiji Era (1868–1912) changed the manner in which most Samurai lived their lives. The new government disregarded the Samurai’s skills as great fighters and defenders of Japan’s honour. Stipends, previously paid to Samurai for their service to Japan, became a thing of the past. Swordsmen also found themselves without work, because Japan was now importing modern instruments of war (such as guns). In many cases, swordsmen took on other crafts, such as the construction of horseshoes, to which they could apply their skills. The Samurai, however, most often refused to accept the disgrace of taking on jobs for the sake of supporting themselves and their families. Some Samurai committed Seppuku, thereby manifesting a preference to die an ‘honourable’ death in lieu of declining into what they perceived to be a sub-standard socioeconomic class.

For those who valued the Samurai traditions of their forefathers, there was hope for a future for the many martial Ryu that had been constructed of techniques capable of addressing the full spectrum of combat inevitabilities. In an effort to preserve the many lessons learned during battle, martial Ryu would be documented by an accounting or logging of techniques.

Martial Ryu techniques were classified in several ways. Some were characterized as emanating from a particular position, i.e. stationary, moving, seated, kneeling or lying. Techniques could also be subcategorized into fist, foot, throwing and grappling methods, any of which may or may not have been used in tandem with weapons. As the practitioners of a particular Ryu classified and systematized their techniques into individual categories, the martial arts began to take the shape of separate disciplines, each falling under a quintessential, philosophical umbrella and methodology. After the techniques of a Ryu were documented and then classified into distinct martial arts categories, a martial Ryu or unique methodology became bona fide and would be recognized by others as an autonomous entity.

It should be the case that the more time a Ryu, composed of individual arts, had to evolve, the greater would be the breadth of techniques under its umbrella. The martial Ryu that proliferated during early Samurai times survived many generations by being passed down within Samurai families. These Ryu, known as Koryu, represent the greatest number of martial arts disciplines unified under any distinct Ryu. Having developed prior to the Meiji Era, the traditional Japanese martial Ryu referred to as Kobudo (ancient martial ways) tended to be comprised of just one or a few martial arts and did not evolve over the course of many generations of Samurai service. As I mentioned earlier, during the relatively peaceful Edo period, the Samurai, unlike their predecessors, served as patrolmen as opposed to fighters on battlefields. While this might have resulted in the development of fewer new techniques during this period, I surmise that the Samurai made great efforts to preserve and practise the techniques and strategies of their forefathers. Modifications of old martial arts techniques were probably retrofitted to accommodate the new circumstances in which the Samurai now found themselves.

A ‘career’ Samurai’s life centred upon the study of all of the techniques of a Ryu. When the Samurai’s duty to Japan became defunct, however, he had to split his time between his martial study and practice, and his other occupational responsibilities. Within the course of his life, the Samurai now had less time to develop his martial ability and fewer opportunities in which to use his skill to fend off a real attack. The separation and classification of groups of techniques into different categories and individual martial arts afforded a part-time practitioner a greater chance of mastering all the techniques of a particular class during his lifetime.

Individuals today who have creatively integrated the martial arts into a full-time career can live the holistic lifestyle of the martial arts by practising and sharing it with others who see the value in the discipline and lifestyle. Others may choose to utilize martial arts techniques in contemporary law enforcement and the security professions. While the latter can be a great forum in which to test one’s skill, regular ‘off the job’ training must be maintained for martial acuity and to keep the body fit for optimal performance.

The Individual Martial Arts Disciplines

The oldest martial arts of the Samurai developed around a primary weapon, the Samurai sword. Ken-Jutsu, techniques in the unsheathed use of the sword, focused on every aspect of blade offence and defence, from cutting, thrusting and blocking to the strategy and practice of fencing. Other auxiliary weapons, such as the Naginata (glaive), Yari (spear) and Tanto (knife), modelled their techniques after Ken-Jutsu. The weapons-free martial arts employed by the Samurai also evolved from the manner in which the Samurai sword was used. These techniques were developed for occasions of an ‘emergency nature’, such as when a Samurai’s sword became non-functional during battle due to damage to the weapon.

Ken-Jutsu.

The techniques of the weapons-free art of Aiki-Jujutsu, or simply Jujutsu, were designed to counter attacks against a Samurai sword-wielding opponent by use of evasive blocking, striking, disarming, throwing and grappling techniques; and in every phase of defence, a connection to the strategy, movements, cuts and blocks of the Samurai sword arts is manifested. These techniques were systematized into an effective, weapons-free martial art. Aiki-Jujutsu is comprised of many elements and is often referred to as the ‘grandfather’ of the Japanese Samurai weapons-free martial arts. Aiki-Jujutsu can be depicted in a hierarchy that includes all the arts that proliferated from it and is separated into three elements, which are characterized by the type of technique and context in which the particular technique could be applied by the Samurai. The elements to which I am alluding are now known as the following martial arts: Kempo-Jutsu, Aiki-Jutsu and Ju-Jutsu (the less comprehensive version). While it might appear that mastery of the techniques of each element or martial arts discipline would lead to a complete understanding of Aiki-Jujutsu, it is my contention that the ‘whole is greater than the sum of its parts’. Let us take a closer look at the Samurai martial art of Aiki-Jujutsu in the way that contemporaries dissected it.

Japanese weapons-free martial arts hierarchy.

Kempo-Jutsu

This weapons-free martial art translates as ‘fist law’ and is the first mode of defence dictating evasive and retaliatory strikes to an opponent. In addition to a safe evasion, Kempo-Jutsu should position the body within adequate range of an opponent in order to use an effective retaliatory strike and possible follow-up (an Aiki-Jujutsu throwing or joint-locking technique). While Kempo-Jutsu has a symbiotic relationship with Aiki-Jutsu and Ju-Jutsu, it can be used alone. On its own, it is a martial art comprised almost entirely of blocks, strikes, and evasive and invasive movements. The strong strategic tactical element of the art provides for efficiency of movement, powerful strikes and the quick execution of follow-up techniques. This is why I characterize it as a most critical first method of defence for the unarmed Samurai.

In the more advanced levels of Kempo-Jutsu, the student is taught to direct strikes toward the more ‘sensitive’ areas of the human body in a quick, explosive manner. These ‘precision’ strikes were designed to penetrate the unprotected or lightly protected joint areas of the body that were not covered by heavy Samurai armour. These areas were similar to the targets used by the sword-wielding Samurai.

Almost every part of the hand can be used to strike targets, such as an opponent’s eyes, throat, ears, armpits, groin, ribs and so on. The martial art’s complex hand-shapes are intricately similar to the way in which one ‘finger spells’ in sign language. These hand-shapes, capable of cutting through the air at speeds much greater than the tightened fist could ever travel, are strengthened by the tightening of the hand and bending of the fingers and thumb just prior to impact. While Kempo-Jutsu does utilize the fist in its arsenal of strikes, the ‘precision strikes’ are used to spear, clip, slash and hook an opponent’s vital areas in a debilitating and sometimes lethal way. (Since this book is focused on the fundamental techniques of the art, I will not elaborate upon the use of ‘precision strikes’.)

Kempo-Jutsu.

The closed fist covers more surface area than the open hand, creating more wind resistance as it ploughs through the air. Upon impact, the striking energy is dispersed throughout the entire fist, rather than focused on a particular point. Many closed-fist striking techniques are taught in the elementary levels of Kempo-Jutsu. Ideally, if you were to use a closed fist to strike at an opponent, you would do so with the intention of hitting with the first two knuckles of the fist in order to achieve a more penetrating effect. Often, in practice, this fails to occur due to a lack of speed, accuracy and proximity to an opponent, and/or the quick movement of an opponent out of harm’s way. The closed fist does, however, provide the ‘student-level’ practitioner a ‘safe’ way to strike because (1) the closed hand is less likely to be injured during a strike, and (2) its greater surface area makes it more likely to hit some part of its target.

Impact area on fist.

In the context of real confrontation, Kempo-Jutsu provided a chance for a Samurai to begin to injure and distract his opponent, setting him up for follow-up techniques, which include the devastating throws, joint-locking and groundwork techniques of Aiki-Jujutsu.

Aiki-Jujutsu: Second Method of Defence

The next major step in the defensive strategy of the Samurai entailed sword disarming, referred to as ‘Tachi Dori’. This technique involved seizing the Samurai sword from an opponent and using it against him or securing it from being drawn from its scabbard and subsequently performing an Aiki-Jujutsu throwing, joint-locking or choking technique. If an unarmed Samurai had been the opponent and there had been no sword to use in defence, the Aiki-Jujutsu technique would follow immediately subsequent to the Kempo-Jutsu evasive or invasive movement and strike.

Tachi Dori.

I suggested earlier that the martial arts of Aiki-Jutsu and Ju-Jutsu manifest as the throwing and grappling elements of Aiki-Jujutsu, in which case one might wonder (1) what unique characteristics separate both martial arts into two distinct disciplines, and (2) can they really stand alone as two different martial arts? The following should provide some answers to these questions.

Aiki-Jutsu throw.

Aiki-Jutsu

Aiki-Jutsu, the martial art of harmonizing or blending an opponent’s energy with one’s own internal energy, is used against an opponent who attacks with a perceivable momentum to a particular direction. Once the direction of the momentum or force is realized by the skilled Aiki-Ka, the Aiki practitioner, he blends with it and redirects it according to his needs, as opposed to colliding with the force, which would, in effect, ‘stop it in its tracks’.

A practitioner of Aiki-Jutsu utilizes the striking and evasive techniques of Kempo-Jutsu in order to position his body close to an opponent. He then follows with linear, diagonal or circular movements to redirect an opponent’s energy via a wrist or arm lock, throw or a combination of these techniques. There are two equally effective methods to facilitate an opponent’s momentum from exhausting before redirecting the opponent or guiding the opponent along the same plane or path. One method is accomplished intuitively (having achieved ‘Mushin’ or ‘no-mindedness’ during uncontrived combat) by blending with an attack at the most opportune moment, when an opponent fully commits to a course of attack and cannot adjust to a different direction. The other method makes use of Atemi, the striking techniques of Kempo-Jutsu, to relax and distract an opponent just prior to an Aiki-Jutsu throw. An instantaneous, tactical choice of strikes is employed to help shackle the opponent’s momentum. The goal is to redirect or continue his movement in the same direction as he is already going, thereby committing the opponent en route