28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

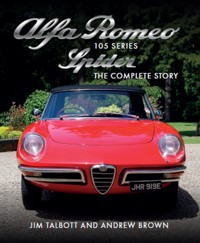

The Alfa Romeo 105 series Spider is one of the most admired drop-head sports cars to come out of Italy. Launched in 1966, its radical new look was not immediately welcomed. As prospective buyers gradually warmed to the model, enhancements were introduced including more powerful engines and higher-spec body and interior fittings. Despite its inauspicious start, production of this much-admired car lasted for twenty-seven years, finally stopping in 1993. Jim Talbott and Andrew Brown pay homage to the 105/115 series Alfa Spider. With over 330 photographs, many specially commissioned, this new book describes the Alfa Romeo company history including its philosophy of incorporating driver appeal into all of its products, resulting in some of the most desirable vehicles of their age; it details the evolution of the 105/115 series through four distinct body styles; lists the technical design specifications and every major version of the Spider and finally, discusses the issues and challenges of finding and owning a classic Spider.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 284

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

OTHER TITLES IN THE CROWOOD AUTOCLASSICS SERIES

Alfa Romeo 916 GTV and Spider

Alfa Romeo Spider

Aston Martin DB4, DB5 & DB6

Aston Martin DB7

Aston Martin V8

Audi quattro

Austin Healey 100 & 3000 Series

BMW M3

BMW M5

BMW Classic Coupés 1965–1989

BMW Z3 and Z4

Citroen DS Series

Classic Jaguar XK: The 6-Cylinder Cars 1948–1970

Classic Mini Specials and Moke

Ferrari 308, 328 & 348

Ford Consul, Zephyr and Zodiac

Frogeye Sprite

Ginetta Road and Track Cars

Jaguar E-Type

Jaguar Mks 1 and 2, S-Type and 420

Jaguar XK8

Jaguar XJ-S

Jensen V8

Jowett Javelin and Jupiter

Lamborghini Countach

Land Rover Defender

Land Rover Discovery: 25 Years of the Family 4×4

Land Rover Freelander

Lotus Elan

MGA

MGB

MGF and TF

MG T-Series

Mazda MX-5

Mercedes-Benz Cars of the 1990s

Mercedes-Benz ‘Fintail’ Models

Mercedes-Benz S-Class

Mercedes-Benz W113

Mercedes-Benz W123

Mercedes-Benz W124

Mercedes-Benz W126

Mercedes SL Series

Mercedes SL & SLC 107 Series 1971–2013

Mercedes-Benz W113

Morgan 4/4: The First 75 Years

Peugeot 205

Porsche 924/928/944/968

Porsche Boxster and Cayman

Porsche Carrera: The Air-Cooled Era

Porsche Carrera: The Water-Cooled Era

Range Rover: The First Generation

Range Rover: The Second Generation

Reliant Three-Wheelers

Riley: The Legendary RMs

Rover 75 and MG ZT

Rover 800

Rover P4

Rover P5 & P5B

Rover SD1

Saab 99 & 900

Shelby and AC Cobra

Subaru Impreza WRX and WRX STI

Sunbeam Alpine & Tiger

Toyota MR2

Triumph Spitfire & GT6

Triumph TR6

Triumph TR7

VW Karmann Ghias and Cabriolets

Volvo 1800

Volvo Amazon

JIM TALBOTT AND ANDREW BROWN

First published in 2019 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2019

www.crowood.com

© James Talbott and Andrew Brown 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 650 0

The information in this book is correct to the best of the authors’ knowledge. The authors and publishers do not guarantee accuracy and disclaim any liability incurred in connection with use of the data published.

CONTENTS

Foreword by Jon DooleyDedication and AcknowledgementsAlfa Romeo 105/115 Series Spider TimelineIntroductionCHAPTER 1A BRIEF HISTORY OF ALFA ROMEO 1910 TO 1966CHAPTER 2ALFA ROMEO DESIGN CONCEPTSCHAPTER 3THE SPIDER 1600 (DUETTO)CHAPTER 4THE 1750 SPIDER VELOCECHAPTER 5THE SPIDER 1300 JUNIORCHAPTER 6THE SERIES 2 1750 SPIDER VELOCE – ‘KAMM TAIL’CHAPTER 7THE SERIES 2 2000 SPIDER VELOCECHAPTER 8THE S2 1300 AND SPIDER 1600 JUNIORCHAPTER 9THE ‘AERODINAMICA’ – SERIES 3 SPIDERCHAPTER 10THE SERIES 4 SPIDERCHAPTER 11OWNING A 105/115 SERIES SPIDERAnomaliesUseful ContactsIndexFOREWORD

Holidays in Italy became much more accessible during the sixties. People who took those holidays came home imbued with the sunshine, the style and the optimism of a country enjoying its economic miracle. Sitting in a roadside café, nothing conveyed the joy and style more than the Alfa Spider, not just in its design but in the way the Italians expressed themselves, a combination of la bella figura and la passeggiata colla macchina. Although the Spider is a two-seater, around town it would often come into sight with three fine-looking girls sat on the back of the cockpit. Ah, the freedom before health and safety! Out of town you would be treated to the rasp of an Alfa exhaust and the gobble of twin Webers, though you needed to check whether it was a Spider or a GTV, or the supposedly humble Berlina or Super.

The design of the first Spiders, the boat tails of the 105 series, arrived in 1966, and as is so often the case with Alfisti, it wasn’t immediately accepted as better than the predecessor. Funnily enough, the first comments were that it was a bit dated. Only when you started to use it did you discover that it was a step forward in usability, with a hood system that worked very well, and a decent boot.

Jon Dooley.JON DOOLEY

For a ‘dated’ design it lasted phenomenally well, with updates along the way. I remember encountering the first S4s out in California in the late eighties, not least when visiting the late and lamented Martin Swig and his Alfa franchise in San Francisco, all under one roof with another twenty-three franchises. By that time the Spider was becoming a classic, and the opportunity to buy new ones, especially the attractive S4, was too good to miss, even for several of my friends who were just looking for a nice car.

Across the decades, the Spider in its various guises symbolized the best of Italian design, all over the world – design not just in its overall line, but in the detail. Quite small details within the interior actually gave pleasure: the instruments, the steering wheel, the switches, the door handles, the toggles for the seat adjustment, the handbrake. Even the things that felt strange to begin with made sense with use. Then there was the mechanical side: the responsive engine and the delicious gearbox, and the steering, full of old-fashioned feel, which made you feel part of the car, at one with it.

My own background with Alfa goes back over five decades. I have been lucky enough to enjoy not just huge friendships with many members of the UK Alfa Owners Club, but also with those abroad. I have been even luckier in being able to sustain a presence in racing Alfas for over four decades, to satisfy the ambition of seeing this famous marque winning against others. I never expected to be able to continue beyond the first year, and it goes without saying that I feel enormous gratitude to everyone who helped and supported me.

I also saw how Alfa worked internally by working for the company for three years, years that probably saw the peak of Spider sales. My competition activity was chiefly in touring cars, so I never raced one of these Spiders. However, the times I drove a Spider brought home the delights of the lack of mass – as well as the lack of protection – above shoulder height as well as the shorter wheelbase. All those drives remain in the memory, stimulating and colourful.

Jon campaigning his GTV6 in the British touring Car Championship.JON DOOLEY

I also had an eighteen-year period with an operation carrying out restorations, at the level they were in the eighties and nineties on cars that at the time were of relatively low value. We got to know the issues and challenges, although generally the standards applied had to be contained because of cost limitations. However, I well remember the owner of a near perfect – indeed more than perfect – Duetto, who would come in on a Saturday morning to search our boxes of original nuts and bolts to fit on his concours example. We thought that was somewhat eccentric, but he was actually completely right. He did, however, suffer a mark-down in the UK AROC Concours, which aimed at originality, as his car was judged to be in a much better state than when it had been delivered new by Alfa!

The authors of this book, Jim Talbott and Andrew Brown, have been colleagues and virtual partners within the AROC for most of my decades spent there. They have owned and lived with Spiders themselves, so this book draws on a great deal of accumulated hands-on knowledge and experience. People who have themselves worked on their cars know, from the toil and suffering while doing so, and from the joy when at last they are able to go down the road afterwards, the issues at a detailed level. They tackle, in great detail, the myriad variations made to these cars over the years and for different markets. This is an ongoing challenge, but their book is a critical tool to anyone maintaining or restoring a Spider.

The classic car interest takes two clear pathways: cars for competition, and collectible original cars for road, display and social use. Competition cars are expected to have items fitted or removed as allowed, to make them effective on the track. The opposite applies to collectibles, where retained originality is at the core. There is little point in owning a non-original collectible, and restoration is therefore a dangerous and challenging field, as it is easy to destroy originality by fitting the wrong replacement parts or applying the wrong techniques. I often think of the antique furniture field, where restoration is generally regarded as detrimental. I believe this will be even more relevant as time goes on, for classic cars and ‘barn-find’ cars are now fetching significant sums if they are unmolested, despite their sometimes parlous condition.

This knowledge will also be invaluable to aftermarket makers and suppliers of parts, who face the challenges of Alfa’s continual evolutions and variations in period.

It is not a bad plan, when looking at buying an interesting car, to begin acquiring literature, workshop manuals and parts books a year or two in advance. This can prevent you buying the wrong car or just paying too much. As a mistake can cost you thousands, a book such as this counts as an investment offering a high multiple.

Jon Dooley

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to the late David Edgington mbe, co-founder of EB Spares, whose enterprise, support and friendly help enabled many Alfisti to keep their Alfa Romeos, the 105 series in particular, on the road.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the following people and organizations who helped with the production of this book, as well as the many Alfa owners who patiently supported us during photographic sessions. We would also like to thank all the owners of cars that were photographed at events, but who were not present at the time and are uncredited.

The following are Spider owners featured in this book:

Marilyn Butt

Neville Byford

Ciro Cargiulo

Paul Conway

Alf Dimaria

Louise Farmar

Jeremy Kitson

Richard Norris

Stephen Paddock

Stuart Taylor – AROC 105 /115 Series Register Secretary

Photographs were taken by Andrew Brown unless otherwise credited. In particular we would like to thank Jeremy Kitson, Nick Clancy, and Auto Italia magazine – also Phil and Michael Ward, David Boreham, Mike Denman, Ray Radley, Neil Jaffe of Chequered Flag International, Marina del Rey, USA, Chris Savill, Juan Martinez of Driver Source, Houston, Texas, USA, Stuart Taylor, Paul and Carol Jaggard, Elaine Talbott.

To illustrate the numerous variations of the 105 series Alfa Spider, many of the photographs in this book were taken at classic car events. The authors and their helpers relied on finding cars and ‘snapping’ them when the opportunity arose. Other sources include the Alfa Romeo Archive at Arese, and classic car dealers who had rare Alfa Spiders for sale and kindly allowed us to publish photographs of them in this book. Cars belonging to the featured owners were specially posed for photography.

We would also like to acknowledge the photography locations: many photographs were taken at the Alfa Romeo Owner’s Club, classic and Italian car shows and motor racing events, including the following:

Duxford Aircraft Museum, /www.iwm.org.uk/Visit/IWMDuxford/ (AROC event)

North Weald Aerodrome, Merlin Way, North Weald CM16 6HR

Goodwood Racing Circuit, /www.goodwood.com/ (Classic Alfa track day)

Stanford Hall, /www.stanfordhall.co.uk/ (AROC event)

Boughton House, /www.boughtonhouse.co.uk/ (AROC event)

The Historic Dockyard Chatham, /thedockyard.co.uk/ (AROC event)

Castle Hedingham, /hedinghamcastle.co.uk/ (Classic Car event)

Zandvoort Motor Racing Circuit, /www.circuitzandvoort.nl/ (Dutch Alfa Owners Club event)

Spa-Francorchamps Motor Racing circuit, /www.spa-francorchamps.be/ (6 Hours race weekend)

We would also like to thank Marco Fazio, Historical Services Manager, FCA Heritage, and Gemma Perrone at the Central Documentazione, Museo Alfa Romeo, for their advice and help with photographs and archive images, and for access to the publicity material used in this book.

We would also like to thank the following for their personal help and guidance:

Neville Byford

Chris Savill

David Edgington

Mike Spenceley

Les Rose

Roger Dykes

Jamie Porter

Titus Rowlandson

Richard Leggett

Mario Lavergata

Finally, we would particularly like to acknowledge the assistance of Jon Dooley in the production of this publication, for his foreword and for his technical help and guidance.

DATA

The specification tables that appear after each section were compiled from various sources including Alfa Romeo publications, archives and contemporary motor magazine road tests. Sources of data can differ and the authors have chosen to include the most widely published specifications. Alfa Romeo Spiders were also assembled in South Africa and specifications for these models may vary.

Marco Fazio.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

ALFA ROMEO 105/115 SERIES SPIDER TIMELINE

1600 Spider/Duetto 1966–1967. Alfa Romeo announced the new 105 series Giulia Spider on 10 March 1966 at the prestigious 36th Geneva Motor Show. A build of 5,946 left-hand-drive Spiders of chassis/model type 105.03 is recorded, and 379 right-hand-drive cars of chassis/model type 105.05. Production tailed off in 1967 with the introduction of an expanded range, though it continued to be sold alongside the 1750 Spider Veloce while stocks lasted.

1750 Spider Veloce 1967–1969. Launched at the Brussels Motor Show in January 1968. Model type 105.57, right-hand-drive 105.58. At its launch it was priced at the same level as the 1600. The launch of the US 1750 Veloce and associated models was delayed until early 1969; they continued to be sold in this market until the end of 1970.

Spider 1300 Junior 1968–1969. In June 1968 Alfa Romeo launched a budget, lower-capacity model, the Spider 1300 Junior. A total of 2,502 left-hand-drive Spider Juniors were made (105.91), and 178 right-hand-drive (105.92). It was not sold in the US.

Series 2 1750 Spider Veloce 1970–1971. At the October 1969 Turin Motor Show Alfa Romeo announced a revised 1750 range for the 1970 model year. The Spider was comprehensively revised, and the new model style became known as ‘Coda Tronca’, shortened tail, or Kamm Tail Spider, and in some markets ‘Fastback’. This general shape continued for all subsequent models up to the Giulia Spider’s demise twenty-two years later, in 1993.

Series 2 2000 Spider Veloce 1971–1982. In June 1971, Alfa Romeo announced its Giulia 2000 range at Gardone, Brescia. The Spider, apart from mechanical revisions, received the smallest number of changes. Production for the right-hand-drive market ceased in 1977.

Series 2 Spider 1300 Junior 1970–1977. In 1970 the 1300 Junior received the Kamm Tail body treatment. It continued with the same model designation as before, 105.91. Production of the Spider 1300 Junior ceased in 1977. A total of 4,557 Spider 1300 Juniors had been produced by the end of 1977.

Series 2 Spider 1600 Junior/1600 Spider Veloce 1972–1981. In 1972 the Spider 1600 Junior was launched alongside the existing 1300 model. Production ceased in 1981, with 4,848 Series 2 Kamm Tail Spider 1600 Juniors manufactured.

Series 3 Spider ‘Aerodinamica’ 1983–1989. Alfa Romeo launched the Spider ‘Aerodinamica’ at the Geneva Motor Show in March 1983. At the 1986 Geneva Motor Show, Alfa Romeo presented an additional model, the 2-litre Quadrifoglio Verde/Green Cloverleaf/QV, serial 115.60. At the same time the other models in the Spider range were updated. The 1.6 now carried the model designation 115.62 and the 2-litre 115.66.

Series 4 Spider 1990–1993. In January 1990 the Series 4 Spider was presented at the Detroit and Los Angeles Motor Shows. Its European launch was at the Geneva Motor Show in March. After twenty-seven years in production the final Alfa Romeo Giulia Spider, a 2-litre Veloce, rolled out of the Pininfarina works in 1993. Production of the 1.6-litre ceased in 1992.

INTRODUCTION

Why another book about the 105/115 series Alfa Romeo Spider? There have been many excellent books written about the 105/115 series Alfa Romeo Spider. Many of these describe the cars in depth, covering development, styling, technical and performance details to satisfy Alfa enthusiasts of all types. History does not change, so why do we need another book? Whilst debating this issue the authors decided that the more personal aspects of ownership had not been covered to any great degree in a book, although some enthusiast magazines had featured owners’ cars and their opinions about them.

It was decided that this might be the way to go, and that the book should be aimed at classic car enthusiasts who perhaps had an interest in Alfa Romeo, or were even considering owning one. They might already own a classic Alfa that is not a Spider, but would like to know more about Alfa’s drop-head sports car to see if it might be the next on the list to acquire. Some, of course, might already own a Spider. But what they all need is a ‘chat’ with a range of owners to understand what Spider ownership entails. They also need to hear from a few experts in the trade about spares and maintenance, and to get advice on how to go about finding the right version of Spider to suit their aspirations.

But what about the technical stuff? Many readers new to the marque would want to know what is under the bonnet, and how the cars were designed and built. So the book would need to go into the technical aspects of the Spider. As the Spider went through four distinct updates and many more sub-versions and modifications, it would be useful to describe these so that the prospective buyer could recognize what is being offered for sale, and make decisions about what is best for them.

But first of all, why is the 105/115 series Spider admired so much these days, and why are good ones so sought after by enthusiasts? Let’s go back and consider what a small sports car really is. As the compact roadster is a largely British concept inspired by Cecil Kimber’s pre-war MG ‘T’ series sports cars, it is natural that many British collectors are drawn to MG and other home-grown products from Austin Healey, Triumph and Sunbeam. It is only the high value of some of these classics that limits their accessibility to many would-be owners. Some, even these days, have not considered buying an Alfa Romeo, or might feel a little unpatriotic by going Italian. Those who do some research and make comparisons might find it an interesting exercise.

Right from the start, drop-head roadsters were developed from manufacturers’ mass-produced saloon cars. The first MGs (Morris Garages) had engines and chassis from Morris road cars. Triumph’s TR2 was based on Standard 10/ Vanguard running gear, MGA – Austin/Morris, Austin Healey Sprite – A35, Sunbeam Alpine – Hillman Husky,Triumph Spitfire – Herald. Whilst new sleek bodies gave these cars plenty of appeal, their driving dynamics were less than exciting, and some would even say ‘boring’. Alfa Romeo also based their sports cars on proven saloon-car mechanicals. The difference was that Alfa saloon cars already had race-bred engines, suspension and brakes that were way ahead of other mass-market manufacturers of the period. That is why Alfa Spiders are as good to drive today as they were when first launched. That is the appeal. At the heart of all Alfa Romeos is a design philosophy that makes them true drivers’ cars, and one reason to own a classic Alfa is to enjoy a driving experience that is no longer available from modern vehicles.

So, this book is as much about the technical design of the Spider as the joys of its styling and of owning one. It is also about the issues and challenges of finding and owning a classic Spider, because there are many pitfalls that the unwary can fall into. It goes into reasonable detail to describe every major version of the Spider so that prospective owners can recognize what they are looking at. It does not describe every nut, bolt and specification, which would make the book a somewhat tedious read to all but those who like lists of numbers and performance graphs. Once they have read this book, the enthusiast should have a reasonable knowledge of every version of the 105/115 Alfa Spider, and be able to decide if owning one would be for them.

CHAPTER ONE

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ALFA ROMEO 1910 TO 1966

Every classic car enthusiast should know the history of Alfa Romeo.

Alfa Romeo is not just another car manufacturer. From the earliest days it decided that racing was a good way to test its cars and gain publicity. Even the pragmatic businessman Nicola Romeo was swept up in the excitement of producing ever more successful racing cars, but financing competition meant producing popular road cars, and whilst the company did make some outstandingly good cars, they didn’t always find a big enough market. A certain lack of commercial prudence has been a factor throughout Alfa Romeo’s history, and the timely production of some wonderful cars was a repeated factor in saving the company at the last minute. It is the cars that are the heritage. Wonderful to drive and wonderful to look at, they excite an emotion in true car lovers that cannot be readily explained. The fact that Alfa Romeo is still with us is perhaps a miracle that we should all be grateful for.

P3 or Tipo B monoposto racing car.

MORE THAN A HUNDRED YEARS OF CAR-MAKING HISTORY

The birth of Alfa Romeo was not a straightforward one, and the company from which it evolved almost went out of business in 1909. Societa Anonima Italiana Darracq, or SAID, was formed in 1906 by a group of Italian investors with backing from the City of London and licensed by the French Darracq company, which owned the patents, to assemble cars to be sold on the Italian market. The vehicle they offered was aimed at the taxicab market, but was outdated even for the period and not robust enough to withstand the challenges of the undeveloped Italian road system. Sales were poor, and by 1909 the management team, headed by Ugo Stella, was faced with closure. However, two things served to prevent the company’s early demise: an enthusiasm for car making by the management team, and an unsatisfied demand for cars from the Italian public. By 1910 Ugo Stella needed a very different car.

Darracq 8/10HP assembled by SAID from components supplied by the French company.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

The original ALFA badge combined the emblems of the Visconti family and Milan.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

The Italian investors in the company agreed that there was a future in car making, and a new company was formed on 24 June 1910. Anonima Lombarda Fabbrica Automobili, or ALFA, was based in Portello, a north-western suburb of Milan. The new company employed design engineer Giuseppe Merosi as its chief engineer. He had previously worked for Bianchi and Fiat and had a natural talent for automotive engineering. His first design for ALFA was the 24HP. The car was strong, well built and elegant, and could manage 100km/h (60mph): just what the Italian market was waiting for. Merosi went on to design new models, including developments of the 24HP to compete in the car-racing events of the period. 1911 saw ALFA cars entered in the Targa Florio, and whilst they did not win, the company appreciated the promotional value of competition. Thus was created the philosophy that has remained with Alfa Romeo to this day.

An ALFA poster of 1910 showing a 24HP car with the Portello factory and the Milan Duomo in the background.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

Giuseppe Merosi in 1906 whilst working for Bianchi.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

The Merosi family taking a ride in a 24HP.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

A New Investor: Nicola Romeo

By 1915, with World War I raging, ALFA was still not financially secure and a new investor was needed. This came in the form of business entrepreneur Nicola Romeo, whose interest was purely to use the Portello factory for his war materials production business. He immediately turned the company over to making aircraft engines and other war-related products, and no more cars left the factory for the rest of the conflict. Fortunately, components for ALFA’s pre-war cars had been stored away, and these helped the company to get back to car production after the war had ended.

Nicola Romeo bought the whole of ALFA in 1918, and his name was incorporated two years later. The first car to be badged as an Alfa Romeo was the Torpedo 20–30HP. This was a development of the pre-war 20–30HP, which in itself was a development of the original 24HP. It had a 4250cc side-valve straight-4 engine producing 67bhp. It was quite an upmarket vehicle, and expensive by comparison with most cars of the period.

The ALFA 24hP tourer: the first of many Merosi designs.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

40/60 Grand Prix car of 1914.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

Meanwhile Merosi was working on competition cars. He had already designed Alfa’s first double overhead camshaft engine with 4 cylinders and 16 valves. This was used in the first Alfa Romeo Grand Prix car, the 40/60 GP of 1914, but the war intervened and it was not until 1921 that the car was driven by Giuseppe Campari in the Gentleman GP, which was a race for amateurs during the Brescia Speed Week.

The first road car to come from Alfa Romeo after the war was the G1, a luxury saloon with upmarket pretensions. Unfortunately it did not find a market, and only some fifty were produced. Alfa’s first successful post-war car, launched in 1922, was the RL.

Nicola Romeo.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

The RL

Designed by Merosi, it had a straight-6 overhead valve engine of, initially, 2.9 litres and 56HP. The car was strong and reliable, and it soon found an expanding market. Many versions of the RL were developed, and production ran until 1927. The original Normale became the Turismo of 3 litres and 61HP, then the Sport and Super Sport with 71HP. Merosi developed a racing version called the RL Targa Florio with lightened body and more power. Engine capacities went up from 3.1 litres to 3.6 litres and 125HP. Racing driver Ugo Sivocci won the 1923 Targa Florio in an RLTF.

RL Super Sport.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

RL Interior.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

1923 RL Targa Florio with the four-leaf clover symbol.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

He chose to have a four-leaf clover symbol on his car to bring good luck, and this became Alfa’s official racing emblem from that time onwards. Perhaps the most famous racing driver of this early period was Giuseppe Campari, who had continued success with Alfas on the track. However, the company employed many racing drivers, including Enzo Ferrari and, in the 1930s, Tazio Nuvolari. Ferrari would eventually give up driving to manage Alfa’s racing team.

In 1923 a smaller version of the RL was launched as the RM. It had a 2-litre, 4-cylinder engine of 40HP, and both saloon and convertible bodies.

Grand Prix Cars, P1 and P2

In the same year Merosi produced the P1 Grand Prix car, two of which were entered in the Italian GP at Monza. The drivers were Antonio Ascari and Ugo Sivocci. The P1 with its aluminium body and 95HP engine was fast, but its handling did not match its performance. Sadly, Sivocci was killed during practice and Alfa withdrew the cars, which did not race again. Soon afterwards Giuseppe Merosi left the company and Vittorio Jano took over as chief engineer. Recognized as a major talent, Jano had been persuaded by Luigi Bazzi and Enzo Ferrari to leave Fiat and join Alfa Romeo.

Vittorio Jano: Alfa Romeo’s second great design engineer.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

P2 Grand Prix car of 1924.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

He quickly produced a new Grand Prix car that was to become one of the most successful racers of the 1920s: the P2. Its only challenger was the highly successful Bugatti Type 35. At the heart of the P2 was a new 8-cylinder supercharged engine designed by Jano. In 1924 the new engine produced 140HP from its 1978cc capacity. The body was slim and light with minimal frontal area, and it also handled well. The P2 won the inaugural World Championship in 1925, and was victorious in no fewer than fourteen Grands Prix, together with the Targa Florio win of 1930, plus other major events. The victories of 1925 led to the incorporation of a laurel wreath surround to the Alfa Romeo badge.

Jano’s racing engine spawned a range of road-car engines that would define Alfa’s engineering philosophy. They were all aluminium, twin overhead cam units with hemispherical combustion chambers and central spark plugs. In 4- to 6- and 8-cylinder in-line versions, some with single overhead camshafts, these engines powered all Alfa’s road cars until after World War II.

Jano’s 8-cylinder racing engine of 1924.CENTRO DOCuMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

Jano’s Road Cars

The first of Jano’s road cars was the 6C 1500, a small, elegant and very sporty vehicle in the smaller-capacity engine class, which was a new venture for the company. The 6C 1500, in various body styles, went on sale in 1927 and was an immediate success. Independent coach-building companies designed bodies for the Alfa chassis, with versions by, amongst others, Touring, Garavini and Castagna. Perhaps the most sporting was the Mille Miglia Speciale, bodied by Zagato.

6C 1500.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

The 8C 2300 was produced in a variety of body styles.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

P3 or Tipo B monoposto racing car.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

An increase in engine capacity resulted in the 6C 1750 in 1929, with many elegant and sporting bodies by the Carrozzeria. In 1931 Alfa Romeo was ready to bring an 8-cylinder road car to the market, and the 8C 2300 was born. This was derived from the 6C 1750 but had a supercharged in-line engine, which was in effect two 4-cylinder engines joined together. The cams were driven by a gear-train between the two engine blocks. Alfa made both long- and short-wheelbase versions, and again, the independent body makers soon launched a great variety of styles that included cabriolets, roadsters, coupés and spiders. A 6C 1900 followed in 1933.

Following the success of the P2 Grand Prix car, Jano designed Alfa’s next racer, the P3 with 2.7 litres and 215HP. Unfortunately its potential was not immediately realized, as financial problems obliged Alfa to withdraw from racing in 1933. Whilst the 6C road cars were selling well, the 8C 2300 proved too expensive and sales were poor. Increasing losses led to the Italian government providing investment funds from the IRI (Instituto Ricostruzione Industriale), which gave them a measure of control over the company. What was needed was a less expensive road car: Jano therefore increased the capacity of the 6C to 2309cc, and a new six- to seven-seater saloon was launched as the 6C 2300. This car went on to be produced in many versions until 1939. Undoubtedly the fact that Benito Mussolini loved Alfas and could see that racing could promote his regime was an ingredient.

Despite the company’s financial problems, or perhaps because it was now supported by the government, the management resurrected its support for the development of competition cars, and Jano produced many successful racers, from the 8C 2300 Le Mans, Monza and 8C 2600 Le Mans cars, to the Tipo A and Tipo B, P3 racers.

The Tipo B was particularly successful, and this led to the Tipo C with initially 330HP. The Bimotore appeared in 1935 with two engines, which were modified Tipo B units. One was conventionally mounted at the front, and the other at the rear behind the driver. The combined capacity was over 6 litres, which produced 540HP. Despite this, it could not beat the German teams from Mercedes and Auto Union, who dominated Grand Prix racing at the time. The company reverted to the Tipo C, from which was developed the 12C in 1937. This was a 4.5-litre, 12-cylinder single-seater with 430HP. Sadly, the high performance of the car was largely negated by its unreliability. When it was forced to retire from the Italian Grand Prix with a failed rear axle, it is said that Jano’s will to design more Alfa racing cars was broken, and he left the company soon afterwards.

The 8C 2900

During the late 1930s Alfa Romeo produced ever more exotic road cars, culminating in the 8C 2900. It came in a variety of body styles, and was the ultimate sporting luxury car as well as a successful sports racer. It was the Ferrari of its day. Paradoxically it would be Enzo Ferrari who took this mantle away from Alfa, and made it his own after World War II. The approach of war meant that the 8C 2900 sold in very small numbers.

8C 2900 B Lungo.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

8C 2900 B Le Mans.CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE ALFA ROMEO – ARESE

The 158 Alfetta

A new racing car was developed from 1936 for the coming ‘voiturette’ formula by engineers at Scuderia Ferrari, and called the 158 Alfetta. Early success before the war indicated its development potential, which would not be fully realized until competition started again in 1946. From 1937, the racing department was taken back from Ferrari to Milan. Pre-World War II Alfa Romeo cars were regarded as being very exotic. Henry Ford, in a 1939 conversation with Ugo Gobbato, is believed to have said: ‘Every time I see an Alfa Romeo pass by, I raise my hat.’