28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

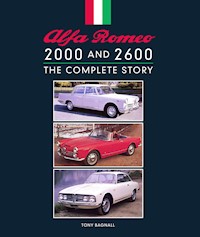

After a period of post-war austerity, in 1957 Alfa Romeo decided it was time to re-enter the market for luxury/executive class cars with a new range designed for the growing number and prosperity of potential customers. Thus, the first models in the new 2000 series emerged, followed by the 2600 series in 1962. That they were not hugely successful, although some 18,540 were manufactured between 1957 and 1966, can be attributed to a number of factors, principally cost. Largely ignored for many years, these cars are now recognized as a significant element in Alfa Romeo's history and this book is a valuable record of their story. Richly illustrated with over 200 colour and black & white photographs, this book introduces the history of the company and its early designs; describes the early Berlina saloon, Spider convertible and Sprint coupe, and their development into the 2600 series; details the evolution of the 1900-based engine into the 6-cylinder 2600 engine; provides a history of the SZ Sprint Zagato; includes information on prototypes, show specials, specification tables, colour schemes and production numbers and, finally, includes a chapter on owning a 2000 or 2600.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Titles in the Crowood AutoClassics series

Alfa Romeo 916 GTV and Spider

Alfa Romeo Spider

Aston Martin DB4, DB5 & DB6

Aston Martin DB7

Aston Martin V8

Audi quattro

Austin Healey 100 & 3000 Series

BMW M3

BMW M5

BMW Classic Coupés 1965-1989

BMW Z3 and Z4

Citroen DS Series

Classic Jaguar XK: The 6-Cylinder Cars 1948-1970

Classic Mini Specials and Moke

Ferrari 308, 328 & 348

Ford Consul, Zephyr and Zodiac

Ford Transit: Fifty Years

Frogeye Sprite

Ginetta Road and Track Cars

Jaguar E-Type

Jaguar Mks 1 and 2, S-Type and 420

Jaguar XJ-S

Jaguar XK8

Jensen V8

Jowett Javelin and Jupiter

Lamborghini Countach

Land Rover Defender

Land Rover Discovery: 25 Years of the Family 4×4

Land Rover Freelander

Lotus Elan

MGA

MGB

MGF and TF

MG T-Series

Mazda MX-5

Mercedes-Benz Cars of the 1990s

Mercedes-Benz ‘Fintail’ Models

Mercedes-Benz S-Class

Mercedes-Benz W113

Mercedes-Benz W123

Mercedes-Benz W124

Mercedes-Benz W126

Mercedes SL Series

Mercedes SL & SLC 107 Series 1971-2013

Morgan 4/4: The First 75 Years

Peugeot 205

Porsche 924/928/944/968

Porsche Boxster and Cayman

Porsche Carrera: The Air-Cooled Era

Porsche Carrera: The Water-Cooled Era

Range Rover: The First Generation

Range Rover: The Second Generation

Reliant Three-Wheelers

Riley: The Legendary RMs

Rover 75 and MG ZT

Rover 800

Rover P4

Rover P5 & P5B

Rover SD1

Saab 99 & 900

Shelby and AC Cobra

Subaru Impreza WRX and WRX STI

Sunbeam Alpine & Tiger

Toyota MR2

Triumph Spitfire & GT6

Triumph TR6

Triumph TR7

VW Karmann Ghias and Cabriolets

Volvo 1800

Volvo Amazon

First published in 2019 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

© Tony Bagnall 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 632 6

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Preface

Series 2000/2600 Timeline

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 2POST-WAR REVIVALCHAPTER 3A RETURN TO LUXURY: SERIES 102, 1957–61CHAPTER 42000 (SERIES 102) BERLINACHAPTER 52000 (SERIES 102) SPIDERCHAPTER 62000 (SERIES 102) SPRINTCHAPTER 72000 PROTOTYPES AND MOTOR SHOW SPECIALSCHAPTER 8SIX CYLINDERS AGAIN: SERIES 106, 1962–6CHAPTER 92600 (SERIES 106) BERLINACHAPTER 102600 (SERIES 106) SPIDERCHAPTER 112600 (SERIES 106) SPRINTCHAPTER 122600 (SERIES 106) SZ SPRINT ZAGATOCHAPTER 132600 PROTOTYPES AND MOTOR SHOW SPECIALSCHAPTER 14COMPETITION HISTORYCHAPTER 15OWNING A SERIES 102/106CHAPTER 16LEGACYAPPENDIX ICOLOUR SCHEMESAPPENDIX IIPRODUCTION NUMBERSAPPENDIX IIIMUSEO STORICO ALFA ROMEO (THE ALFA ROMEO MUEUM)APPENDIX IVTHE ALFA ROMEO OWNERS CLUB LTD (AROC)APPENDIX VHOMOLOGATION CERTIFICATESBibliography

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is always difficult to acknowledge everybody who has contributed to a book in any manner whatsoever, however some individuals deserve mention due to their significant contribution. This book would not have been possible without the enormous amount of help provided by the staff of the Alfa Romeo museum at Arese, in particular Dr Marco Fazio, who is the Historical Services Manager for the entire Fiat Chrysler Automobile (FCA) group, which encompasses the Fiat, Alfa Romeo, Lancia and Abarth marques. His ability to put me in touch with many individuals in this sphere of automobile history has been both remarkable and incredibly helpful. The Arese staff, under the direction of Lorenzo Ardizio, have also been incredibly helpful, in particular Lorenzo himself, who has dealt with my many queries without hesitation or complaint. The unstinting support received from Ing. Giovanni Bianchi Anderloni in respect of Carrozzeria Touring has also been remarkable. Stefano Salvetti, author of Curiosalfa, was really helpful in providing introductions to owners of the photographs of a number of special prototypes and one-off specials. One of the contacts provided by Stefano was Corrado Lopresto, who very generously provided twelve photographs from his archive. No book on Alfa Romeos from this era would be complete without some input from Peter Marshall, who not only gave up some of his time and material, but also provided the initial contacts in Italy. Nina Hendriks, from the Netherlands, went out of her way to assist me with queries relating to her late father; once again I am most grateful to her. Contributions from Nick Savage, Ian Packer and Chris Savill were much appreciated. If I have inadvertently omitted anybody from this list, please accept my apologies. Finally, I am indebted to the various magazine and newspaper publishers/owners who willingly gave their permission for me to quote extracts from the road test reports that have made a major contribution to this book.

PREFACE

As a young boy I was always interested in mechanical things, particularly motor cars and aircraft. My father was what was called in those days a commercial traveller and he had a new car every three years, which also increased my interest. Then one day in 1955 he asked my brother and me whether we would be interested in going to a motor race being held at the Aintree circuit, which was only three miles from where we lived, and so on 16 July 1955 we saw the 1955 British Grand Prix and witnessed Stirling Moss beat his Mercedes teammate Juan Fangio. From that moment on I became a keen supporter of motor sport and saw all the subsequent motor races held at Aintree until the demise of the full three-mile Grand Prix circuit after 1964. While I didn’t then have a specific interest in Alfa Romeos, I did see them racing on at least two occasions. The first was at the April 1956 Aintree ‘200’ meeting where the future Grand Prix driver Jo Bonnier drove his 1900 Super Sprint into first place in the up to 2500cc class of the saloon car race. Then at the same meeting two years later, Louis dei Conti Manduca took part in his 1900 TI and finished in second place in the up to 2600cc class in the saloon car race.

Many years later, after owning a range of ordinary cars, I became entitled to a lease car at the organization I then worked for. The initial range was quite restricted and I chose a 1.8 litre Vauxhall Carlton, which proved to be reasonably satisfactory. When in 1991 the time came to change the car, however, the choice of available cars had been extended significantly, although it didn’t include the Lancias I was very keen on at the time. Then I noticed that Alfa Romeo was on the list and that there was a local dealer in Liverpool, so I went to have a look. Apart from a white late Series 4 Spider in the showroom, there was also a red 2-litre 164 saloon. The salesman with the usual sales pitch said, ‘Once you’ve driven this you won’t want to drive anything else.’ To my surprise he was absolutely right. I immediately felt at home in the 164 and was most impressed by it. That was the start of my love affair with Alfas and I haven’t been without one since. I had three 164s and purchased a 145 for my wife. My interest in classic Alfas started with an Alfetta GTV and then my current 2600 Sprint, which I have owned since 2005.

As an Alfa owner for twenty-seven years I think that I qualify for the title ‘Alfisti’. Apparently dating back to the 1920s, Alfisti was the name given to Alfa Romeo enthusiasts in the same way that Ferrari enthusiasts are labelled ‘Tifosi’.

In this book I have relied upon the production numbers provided by the late Luigi Fusi, who was the acknowledged expert on Alfa Romeo history (see Appendix II). I wish to clarify this because different statistics have appeared in various books relating to Alfa Romeo. Performance figures, too, in particular acceleration from 0–60mph, have been obtained from various road test reports that often differ and so I have used the most optimistic results. The maximum speeds quoted are extracted from the homologation certificates that Alfa Romeo submitted to the Italian State, although sometimes the speeds quoted in marketing material and other sources may be slightly different. I make no apology for my fascination with the outputs of the various Italian carrozzieri during the 1950s and early 1960s, in particular their relationship with Alfa Romeo, and I have included them in some detail.

SERIES 2000/2600 TIMELINE

1957

The 2000 (Series 102) Berlina and 2000 Spider go on saleCarrozzeria Vignale commences production of a small number of a 2+2 coupé based upon the 2000 chassis

1960

The 2000 Sprint introducedFNM in Brazil commences production of the 2000 Berlina under licence

1961

Production of the 2000 Spider ceases

1962

Production of the remaining 2000 cars ceases in Italy

1962

The whole range of the new 2600 (Series 106) models goes on sale, including the Berlina, Spider and Sprint versions

1965

The De Luxe version of the Berlina produced by OSI goes on saleThe 2600 SZ Sprint by Zagato is introducedThe 2600 Spider ceases production

1966

The 2600 Sprint ceases production

1967

The 2600 SZ Sprint ceases productionThe 2600 De Luxe by OSI ceases production

1969

Production of the Berlina in Italy ceases with the final 2600 Series vehicle

1986

The final version of the 2000 is produced in Brazil, by which time it has been through several iterations, ending with the engine size increased to 2310cc

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

It is unthinkable to write about Alfa Romeo today without revisiting its history in order to gain a thorough understanding of what the marque stands for. Even though it is uncertain whether the quotation that has been attributed to Henry Ford should read, ‘Every time I see an Alfa Romeo pass by, I raise my hat’, or its variant ‘When I see …’, it is clear that Alfa Romeo had made an impact on the legendary Mr Ford.

UNCERTAIN BEGINNINGS

The origins of Alfa Romeo go back to 1906 when Alexandre Darracq, the founder of car companies in both France and England, announced that there was a demand for reasonably priced motor cars in Italy and that, following an approach by a group of Italian capitalists, he intended building a factory near Naples for the construction of Darracq motor cars. Unfortunately, the first three years were disastrous and significant financial losses were incurred. During this period the decision was taken to relocate and a large parcel of land was acquired for a new factory in a district north of Milan known as Il Portello. As the financial position worsened, Alexandre Darracq sold his shares to the Banca Italiana di Sconto, which liquidated the original company and established the Società Anonima Lombarda Fabbrica Automobili (A.L.F.A.). The then managing director, Ugo Stella, knew that things had to change and in 1910 he recruited Giuseppe Merosi, from the Italian car and motorcycle manufacturer Bianchi, as Technical Director.

Giuseppe Merosi was born in 1872 in Piacenza, which is about 65km south of Milan. He qualified as a surveyor and was initially employed as a highway surveyor before collaborating with a friend on setting up a firm that manufactured bicycles. After about two years he then left to work as a demonstrator and tester for O&M, which made sewing machines and motorcycles. Then in 1906, following a short time with Fiat, he joined the Bianchi company as head of the automotive engineering department, where he was responsible for most of the designs produced by Bianchi, including their first shaft-drive car.

At A.L.F.A. Merosi rapidly produced two new designs that were radically different from the previous Darracq models. Whereas these had small single- and twin-cylinder engines, the first A.L.F.A. model was the 24 HP, which was fitted with a 4-litre engine capable of reaching 110km/h (68mph) and proved to be very successful; by 1913 some 200 had been produced. Very soon afterwards a smaller car, the 15 HP, was introduced and similarly sold well, with more than 300 being produced before the First World War. Examples of both the 24 HP and the 15 HP can be seen in the Alfa Romeo museum at Arese.

Just before the outbreak of war in 1914 (Italy did not enter the war until 1915) a powerful new model, the 40-60 HP, was introduced. Among the purchasers of this model, of which twenty-five were built, was Count Marco Ricotti from Milan, who requested a special aerodynamic body for his car. Carrozzeria Castagna, one of Italy’s oldest and most prestigious body builders, was commissioned to design an appropriate body for the chassis. The result was an amazing design inspired by a drop of water and made of aluminium, which increased the top speed of the original design from 125km/h (78mph) to 139kmh (86mph). The doors were flush with the bodywork, the windows were effectively round portholes and there was a broad wraparound windscreen. A year after its construction the roof was removed, thus turning it into an open car at the expense of the previous aerodynamic benefits. The original was lost many years ago, but a replica was constructed from the original drawings as a tribute to Castagna’s ingenious design and is now on display at the Alfa Romeo Museum at Arese.

An example of the first A.L.F.A. 24 HP, 1910, at Arese.

A.L.F.A. 15 HP, 1911, at Arese.

The replica A.L.F.A. 40-60 HP Aerodinamica, 1913, at Arese.

24 HP engine as used in the Santoni Franchini biplane, 1910.

In 1910 another milestone in the history of Alfa Romeo took place when Giuseppe Merosi allowed two technicians, Antonio Santoni and Nino Franchini, to use part of the Portello workshops to construct an aeroplane. Naturally the plane was powered by an A.L.F.A. engine, one of the first 24 HP engines. The plane, piloted by Franchini, flew well and was used for training purposes until it was destroyed when a hangar collapsed onto it. Thus began the relationship between A.L.F.A., and eventually Alfa Romeo, with the aero engine industry.

THE BADGES

Does the Alfa Romeo badge really show a human figure being eaten by a dragon? The story starts in 1910 with the birth of A.L.F.A.; in designing the insignia, Merosi decided on a combination of the coat of arms of Milan and that of the Visconti family. It is claimed that the badge was suggested to Merosi by one of his staff who saw the insignia of the Visconti family above an entrance to the Castello Sforzesco in Milan when waiting for a tram. The castle had been home to the Visconti family for nearly a century from 1358. The most fanciful story for the symbol’s origin claims that the legendary founder of the dynasty, Uberto Visconti of Angera, killed a biscione (serpent) named Tarantasio that was terrorizing the region around Lake Gerundo in Lombardy. The white shield with a red cross is the flag of Milan. Sometimes known by the Milanese as the ‘cross of St Ambrose’, after the city’s patron, it is said to have been used since the tenth century. The badge as designed enclosed the emblems of Milan (on the left) and the Visconti family within a blue circle. At the top of the blue ring was the word ‘ALFA’ and at the bottom ‘MILANO’, separated on either side by a pair of figure-of-eight knots, heraldic attributes of the Italian royal house of Savoy.

Development of the Alfa Romeo badge.

ALFA ROMEO ARCHIVES

A revised badge was adopted following the acquisition of A.L.F.A. by Nicola Romeo in 1915 and the cessation of hostilities three years later. The basic design was retained but the word ‘A.L.F.A.’ was replaced with ‘Alfa-Romeo’. The next change came in 1925 when, following the racing victories that made Alfa Romeo the Grand Prix Champions of the World in 1924 (the first such championship), a laurel wreath celebrating the achievement encircled the whole badge. The next change came in 1946 when, in recognition of the new Italian Republic, the Savoyard knots were replaced by two wavy lines. Then in 1971 the badge was simplified by deleting the laurel wreath, the word ‘Milan’ and the hyphen between the words ‘Alfa’ and ‘Romeo’, which resulted in a much simpler design.

While the usual Alfa Romeo badge adorns all their cars, there is another symbol that only appears on specially sporting models. This is the green four-leaf clover (Quadrifoglio Verde) on a white diamond background, which came about after Ugo Sivocci won the 1923 Targa Florio in an Alfa Romeo RL decorated with his lucky symbol. Tragically, less than five months later he died while testing a new P1 car that did not have such a symbol painted on it. Since then the ‘Qaudrifoglio’ has appeared on racing and sporting Alfa Romeos as a symbol of good luck. Sivocci’s triumph in the Targa Florio was the first win for Alfa Romeo in a large international event, thus guaranteeing his and his car’s place in the annals of motor racing.

A badge that is not generally associated with Alfa Romeo is the ‘Prancing Horse’ of Ferrari, but its origins, too, are closely related to Alfa Romeo. In 1923 Enzo Ferrari drove an Alfa Romeo RL to victory in the 1923 Circuit of Savio race in Ravenna, having driven a perfect race against stiff opposition. His victory so impressed the spectators that they carried him off on their shoulders. Among the spectators at the finish were the parents of Count Francesco Baracca, Italy’s most outstanding air ace in the First World War, who had been credited with thirty four aerial victories before his death in June 1918. The Count and Countess were so impressed with Ferrari’s performance that they presented him with their son’s personal emblem as a mark of their respect. Francesco had used his family emblem on his aeroplane to distinguish it from those of his colleagues. The emblem, which today is well known as it can be seen on every Ferrari, is a black prancing horse mounted on a yellow shield. In the years up to the Second World War, and before Ferrari started constructing his own cars, the emblem represented Scuderia Ferrari and appeared on all Alfa Romeo cars raced by that team.

The ‘Quadrifoglio’ badge as shown on a Disco Volante at Arese.

Ferrari badge on 8C 2300 Monza.

FIRST WORLD WAR AND THE 1920S

Having reached an annual output of 200 cars before the outbreak of war, A.L.F.A. was immediately pressed into service for the military, manufacturing ambulances, generators, compressors and, under licence, Isotta-Fraschini aero engines. The compressors that were manufactured for the armed forces remained in use for many years thereafter. The company recommenced building cars after the war ended, but progress was difficult in the aftermath of that dreadful conflict and the loss of so many lives. In 1918, having become a public company, expansion took place with the acquisition of several more businesses, including a railway company. Involvement with railways saw the introduction of an early version of diesel engine incorporated in a small locomotive. In the early 1920s the Romeo tractor was produced for a period of five years. This proved to be extremely reliable and had the advantage of running on either petrol or kerosene. Car sales, however, grew very slowly and not a single car was sold in 1922. This fact, combined with the bankruptcy of the Banca Italiana di Sconto in 1921, meant that Alfa Romeo was constantly grappling with difficult financial issues, in particular cash flow.

Merosi’s masterpiece, the 3-litre RL Super Sport, 1925.

Despite these problems Giuseppe Merosi produced a design that is nowadays usually referred to as ‘Merosi’s masterpiece’: the RL, a 6-cylinder, overhead valve engine available in capacities from 3 to 3.6 litres. Despite his successful RL design, which contributed to Alfa Romeo’s growing success with more than 3,000 produced over its five-year life, including the smaller RM version equipped with a 4-cylinder, 2-litre engine RM, Merosi’s standing within Alfa Romeo declined rapidly after several expensive failures. Sports versions of the RL achieved considerable success on the race track, even achieving a first, second and fourth placing in the 1923 Targa Florio with a special highly tuned lightweight version called the TF.

Another view of the RL Super Sport.

1923 Targa Florio RL

The appointment of Vittorio Jano in 1923 as head of the racing department (Merosi remained in charge of touring car production) came at a critical point in Alfa Romeo’s early history. Jano, who was to become Alfa Romeo’s chief designer and was undoubtedly the principal reason for the firm’s remarkable success story during the 1920s and ’30s, was born in 1891 near Turin and obtained a diploma in engineering in 1909, which gained him a job with the truck and bus manufacturer Ceirano. He later moved to Fiat, where he remained until 1923, when Luigi Bazzi, who was being encouraged by Enzo Ferrari to leave Fiat and join Alfa Romeo, suggested Jano as a talented engineer worth recruiting.

The failure of Merosi’s expensive Grand Prix car, the G1, led to Nicola Romeo tasking Jano with the production of a racing car that would uphold the company’s prestige on race tracks worldwide. The result was the legendary P2, which gave Alfa Romeo victory in the first Grand Prix Champions of the World Series held in 1924.

The legendary 1925 Grand Prix Tipo P2.

A 6C 1500 Super Sport, winner of the 1928 Mille Miglia.

Building on the success of the racing P2, in 1927 the 6C 1500 was introduced, followed in 1929 by the 6C 1750. The 6C 1500 was the first car sold to the public that had a twin overhead camshaft engine. In its sporting guise the 6Cs had an impressive racing record: the 1928 Mille Miglia was won by Giuseppe Campari and Giulio Ramponi driving a 6C 1500, while the 1929 Mille Miglia not only saw the 6C 1750 Super Sports model take outright victory, again driven by Campari and Ramponi, but out of the top ten finishers, seven were Alfa Romeos. The 6C 1500 and 1750 ranges were very successful for Alfa Romeo, with almost 1,800 produced up to and including 1929. In fact total production in 1925 exceeded 1,100 units, a level that was not to be achieved again until well after the Second World War. They remained in production until 1933, although larger engine variants continued until 1942.

The collapse of the Banca Italiana di Sconto led to the Italian government creating the Banca Nazionale di Credito as a way of managing the former bank’s collapse. This new bank then became a major shareholder in Alfa Romeo. In 1926 this bank was absorbed into the Istituto di Liquidazioni and then in 1933, under the Fascist government, it was taken over by the state-controlled Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale (IRI). This organization had major investments in much of Italy’s industrial sector and effectively now owned Alfa Romeo, to the extent that the company’s name changed from Ing. Nicola Romeo and Co. to Società Anonima Alfa Romeo.

Having taken to the air as well as on the ground, the 1930s saw Alfa Romeo also take to the water. Wartime experience of manufacturing high quality aero engines resulted in the development of a range of industrial diesel engines that eventually powered motor launches, motor yachts, speedboats and locomotives. Alfa Romeo-powered speedboats were very successful and took several World Class Records over the years.

ALFA AVIO

The perception that Alfa Romeo is only a producer of sporting cars, which many people may have today, is quickly dispelled by a visit to the Museo Storico Alfa Romeo, where some of the first exhibits on display are aero engines. While anyone with the slightest interest in the history of motor sport will inevitably link the name of Alfa Romeo with famous racing cars, drivers and victories, they may be surprised to learn that from the very earliest days Alfa Romeo produced a wide variety of items, not all involving motor vehicles. While the first A.L.F.A. (as it was then) car was produced in 1910, as recounted above, that year also saw its first aero engine, which was installed in a Santoni and Franchini designed biplane.

A.L.F.A. halted car production during the First World War and turned instead to military requirements, including producing Isotta-Frascini engines under licence for military aircraft. Italian aircraft powered by A.L.F.A.-built Isotta-Fraschini engines included the Caproni Ca.3 three-engined heavy bomber and the Macchi M.5 and M.7 flying boats. It is estimated that some 300 aero engines were built in this period.