Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

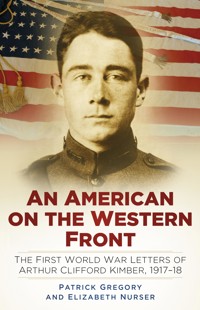

This is the remarkable story of the American First World War serviceman Arthur Clifford Kimber. When his country entered the Great War in 1917, Kimber left Stanford University to carry the first official American flag to the Western Front. Fired by idealism for the French cause, the young student initially acted as a volunteer ambulance driver, before training as a pilot and taking part in dogfights against 'the Boche'. His letters home give a vivid picture of what Kimber witnessed on his journey from Palo Alto, California to the front in France: keen-eyed descriptions of New York as it prepared for the forthcoming conflict, the privations of wartime Britain and France, and encounters with former president Theodore Roosevelt and Hollywood actress Lillian Gish. Kimber details his exhilaration, his everyday concerns and his horror as he adapts to an active wartime role. Arthur Clifford Kimber was one of the first Americans on the front line after the entry of the US into the war and, tragically, also one of the last to be buried there – killed in action just a few weeks before the end of the war. Here, his frank letters to his mother and brothers, compiled, edited and put in context by Patrick Gregory and Elizabeth Nurser, are published for the first time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 671

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To the memory ofNaomi Kimber Marshall

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people have helped in the production of this book: directly and indirectly, people from the modern day and from years past; and we would like to thank them all. To begin with, Mark Beynon of The History Press for commissioning An American on the Western Front; and Clara and George Kimber for their original and vital work after the First World War, work upon which we were able to build.

But we would also like to thank a great many historians and experts, past and present, for their scholarly research. Among them are the late John S. D. Eisenhower and James J. Hudson for their important military and aviation histories of America’s war effort in the First World War; likewise the late Arthur Raymond Brooks, official historian of the 22nd Aero Squadron; and the aviation expert Jon Guttman for his diligent proofreading and suggestions for additional detail to be incorporated in our work. Grateful thanks also go to Blaine Pardoe of the League of World War I Aviation Historians for his research notes and help; and to the AFS Foundation for its invaluable archive.

We would like to acknowledge the support of Professor Andrew Wiest of the University of Southern Mississippi for his scholarly introduction to this book and Mark Taplin, the United States’ former chargé d’affaires at US Embassy Paris. It was Mark who commissioned the mission’s ‘Views of the Embassy’ project in 2013–2014 which focused on the work of American diplomats and volunteers in France following the outbreak of war in 1914: work which was then carried out so ably by Dr Lindsay Krasnoff of the Office of the Historian of the US State Department. I’m indebted to Lindsay for her invaluable research and a later invitation to collaborate in a State Department webinar on the subject.

We would like to acknowledge the help of the staff of the British Library in London, including permissions manager Jackie Brown; the Imperial War Museum; the Service Historique de la Défense in Paris; the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC; the Submarine Force Museum in Groton, Connecticut; library staff of the Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas; and also, and importantly, Conrad Berger of the Library of Congress in Washington DC.

Thank you to cartographer Barbara Taylor for her excellent original artwork and for making our vague map-making ideas reality; and also to the railroads writer and consultant Ken Kinlock who provided valuable advice on otherwise unfathomable century-old American railway timetabling.

Personal thanks go to Elliot Ross for his assiduous end-noting of this book and for his website design, to friends Paul and Denise Wright for their encouragement and help in pursuing the project over these last years; and most especially to my wife and family, Isabelle, Thomas and Elizabeth for all their constant support.

Patrick Gregory

We wish to acknowledge the help of other descendants of Clifford’s brothers who added snippets of information from family memories, in particular Dr Clarissa Kimber, another of George’s daughters. His youngest daughter, Naomi Kimber Marshall, sent the remaining archive, including a number of pictures used here, which had been retained by her mother. Naomi’s death shortly afterwards sadly precludes her seeing the completed book. Anne Kimber, a granddaughter of his elder brother John, sent genealogical information of great interest, and Ghislaine Shelley also added her efforts in France. Michael Over, archivist at Kent College, Canterbury, was able to confirm information about Clifford’s time there. All these, we thank.

We have attributed the ownership of pictures in their captions, and thank all those who have kindly allowed us to reproduce their illustrations in this book. Most of the photographs were taken by Clifford at the front. Thank you to Darren Lusty of The History Press for his skill in enhancing those very old and fragile prints.

Elizabeth Nurser

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Preface by Patrick Gregory and Elizabeth Nurser

Introduction by Professor Andrew Wiest

1 Bantheville, October 1920

2 Letter-Writing

3 Coming of Age

4 The Rush to War

5 Readiness

6 Setting Off

7 Through the West

8 New York

9 Looking Back

10 At Sea

11 England

12 Paris

13 The Flag Presented

14 Bearing Witness

15 First Flight

16 Stung

17

En Repos

18 On the Move

19 Beginners’ Class

20 Dreaming Aloud

21 Bird’s Eye

22 Taking Wing

23 Advancing

24 Finishing School

25 Getting Ready

26 The Waiting Game

27 Delivery Man

28 The 85th

29 On Patrol

30 The 22nd

31 St Mihiel

32 Meuse-Argonne

33 Final Flight

34 Aftermath

35 At Rest

Appendix

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

PREFACE

Arthur Clifford Kimber wasn’t the first American to serve in France in the First World War, nor was he the last to die there. He wasn’t the first person, American or other, to write his thoughts from the Western Front in the form of a diary or letters, or in prose or poetry, nor did he achieve particular distinction in military service while he was there. But what is striking about the letters of Clifford Kimber is the size of the canvas he left behind, one on which we can see not only the portrait of a young man, but also manage to glimpse an image of the United States as it gathered itself for its first proper foray on the global stage and prepared to walk out on to it.

In order to explore these two stories as fully as possible, and flesh them out for the reader, Elizabeth Nurser and I have used a variety of different methods and resources. Small fragments of these letters have been aired once before in extracts contained in the book The Story of the First Flag, compiled by Clifford’s mother shortly after his death. It focused heavily on one aspect of Clifford’s time in France – his mission to carry the first official flag sanctioned by the American Government to France at the beginning of the war – before turning to some other snippets of his life in service there. We are indebted to Clara Kimber for her work, but felt that the time had now arrived to share the letters more fully, to flesh out Clifford’s story and to give it a proper beginning, middle and end as well as put it in context.

In the time that has passed since Clara sat down in 1919 and 1920 to record something of her son, these letters as well as bits of memorabilia and photographs gradually came to be scattered around the world, stuffed in boxes and trunks, in attics and garages and under beds in homes in the United States and Britain, alongside the letters of Clifford’s brother, George. The approaching centenary of America’s involvement in the Great War marked a fitting time to begin sifting through them and compiling them, to publish a representative sample of letters and photographs.

Thus An American on the Western Front sets out to tell these two stories in tandem: that of Clifford’s life and America’s war effort, and in essence mixing the personal and the public. I have attempted to do this primarily through the letters, which Elizabeth and I have edited; but also through a narrative structure that puts Clifford’s story in its place within its historical context, explaining how the country readied itself for and applied itself to the war effort in Europe. In order to help achieve this I have borrowed from a wide range of sources, both academic and private, and I have acknowledged these in endnote and bibliography form and elsewhere. I have not included all of Clifford’s writing, but large and strictly sequential extracts. Nonetheless, partial or not, I hope we have allowed him to tell his story all these years on and that a proper balance has been struck between his letters and the narrative I have fashioned around them.

A century on, we can see afresh the world Clifford left behind so suddenly. We can share a young man’s thoughts and feelings during the last eighteen months of his life as he grew up very fast, during extraordinary times, moving from everyday and humdrum concerns to the sudden realities and brutalities of war. It is, necessarily, the story of a life only part lived, of hopes and dreams cut short. But his letters allow us a vital worm’s eye view of the war, where we can follow his story and that of America from the sunny optimism of springtime California in 1917 to the dank mists of northern France in autumn 1918.

It has been a privilege to share this young man’s life and it is in his memory and that of his colleagues, for their bravery, that this book is written. I would like to thank Elizabeth for her unstinting work and her editing skills and for her agreeing to participate in the project in the first place. I hope the book will be of interest to the general reader as much as to the academic scholar, whether he or she chooses to read it in full or skims through it for certain episodes or facts. Either way, I hope it will add some understanding to the overall picture of America’s role in the Great War and that others may borrow from it in the years to come.

Patrick Gregory

London, 2016

Please keep all my letters carefully. I shall number them and will write the story of my time when I return.

This book is a selection of those letters, sent by Clifford Kimber, a young Stanford University student, to his mother and two brothers, on the ‘adventure of his life’. He wrote 160 letters home, from leaving California and his departure from New York for Europe in May 1917 to his death in September 1918, weeks before the Armistice and the end of the war. Other letters to friends have not survived.

Clifford’s story begins in April 1917, when he was entrusted with an American flag (now in the archives of Stanford University) to present to the French commander of the unit to which he would be attached as an ambulance driver.

American volunteer ambulance units had first developed in the older universities of the east coast as a way of helping the Allies in a non-combatant role while the United States was still neutral. By late 1916 a pro-French fever had spread to colleges on the west coast, and ambulance units were formed at the University of California at Berkeley and Stanford University. Young men like Clifford, already convinced that the Allies, and in particular the French, were fighting for liberty and Western values, threw themselves into the fray.

By the time Clifford’s unit left for France, the United States had entered the war. The flag that had been entrusted to Clifford in April became the first American flag to be raised in the European conflict. However, the ambulance units were still civilian, officially attached to the French Army. As America reorganised its armed forces during 1917, most of the young volunteers joined one or another of the services, and Clifford eventually became a pilot.

Arriving in Liverpool after the Atlantic crossing, Clifford posted a batch of letters as soon as the boat docked. It had been an exhilarating journey across the Atlantic, with boat drills, sightings of flotsam and jetsam from sunken vessels, and dodging submarines near the Irish coast. He exhorted his family back home to type up his correspondence as soon as it arrived, to preserve what he hoped would form a complete journal of his wartime experiences. He expected to edit this journal himself and produce a book when he returned to California.

Clifford wrote completely frankly to his family, just as he would have spoken to them. Early published reports of an exciting experience that he had in New York, protecting the ‘Stanford’ flag from a hijacking by the University of California ambulanciers who were travelling to France at the same time, had resulted in embarrassment:

Please don’t let anything I say in my letters get published at all unless I give permission, or you ALL (not one) really think it all right. I have changed, and I assure you I was thoroughly ashamed of that Times clipping. I have absolutely no desire for that kind of publicity. PLEASE TAKE NOTE.

In telling his story, he not only wanted to capture what he saw in writing, but also in photography and sketches. The letters are peppered with references to drawings, most long lost, and photos which he used to explain or support events. Most of the photos taken before he joined the American air arm were collected and turned into an album by his brother George. Unfortunately, almost all of those taken during his flying days have disappeared. Whether they were lost in transit from France to California when his effects were dispatched by his commanding officer, or later, is unknown – probably unknowable. (We know the photographs once existed because he directed that the ‘plates be sent to his mother in the event of his death’.)

Nonetheless, what does remain of Clifford’s record has been enough – from the perspective of 100 years later – to piece together the story of a boy who jauntily went off to war with romantic idealism and a certainty that he would return, but who after eighteen months had become a man with no illusions about the grimness of war and the possibility of death. The fact that he was not able to edit his story himself means that we have probably lost much that would have interested later generations (he was a keen observer of people, events and, especially, machinery!), but it has allowed us to be with him in the most mundane, as well as terrifying, experiences. We can feel the boredom, the fun, his homesickness, the carefree pleasure of travel on leave, small humiliations, and the thrill of flying and combat in the air.

The remarkable survival of so many letters is due to the conscientious typing up of the letters as they received them, by his mother and his younger brother, George. At least four copies of the letters were made and bound in leather. There is some variation in the text of the letters, but not of sufficient importance or extent to affect the extracts here. Everything relating to Clifford was jealously guarded by his mother and on her death by George. But somewhere along the line, most of the original letters were lost – perhaps they were discarded as redundant when they had been transcribed. How the photographic plates disappeared is a complete mystery. (Other photographs, some of which are printed here, come from a variety of sources. Where known, we have made appropriate acknowledgement.)

In 1999, shortly before her death, George’s second wife, Josephine, packed up Clifford’s effects (which she had inherited) and sent them to me in the United Kingdom. I am George’s second daughter; I had come to England as a student, then married and settled permanently. Josephine could think of no one in the United States who would be sufficiently interested to take them in toto. Like Clifford’s mother and brothers, she hoped that someone eventually would publish an edition of the letters to fulfil Clifford’s intention. I agreed to try, but during the last fifteen years personal matters have intervened and it looked as if more years would pass before there was a proper attempt. Clara E. Kimber, Clifford’s mother, had already published extracts from some of the letters in 1920 as The Story of the First Flag, a beautifully written tribute of a mother to her son. But there is much more in the letters that deserved publication and another version was needed.

Rescue came in the form of my son-in-law, Patrick Gregory. He could conceive of no better time to publish this book than in the centenary of the involvement of the United States in the First World War, and he suggested we collaborate. This book is the result of that collaboration and without his enthusiasm, knowledge, skill and perseverance it would not exist. Thank you, Patrick.

Elizabeth Nurser (née Kimber)

Sudbury, Suffolk, UK

2016

INTRODUCTION BYPROFESSOR ANDREW WIEST

On the morning of 6 June 1994 a telltale roar prompted the crowd around Sainte-Mére-Église to look to the skies. Parachutes popped open all around as 1,000 men tumbled from their aircraft towards the landing zone below. Led by thirty-eight veterans who the French press had dubbed the ‘papys sauteurs’, or ‘the jumping grandpas’, the paratroopers drifted to the ground, with only one of the grandpas sustaining a minor injury. The spectacle gave way to ceremonies and speechifying by a glittering assortment of queens, crown princes, presidents and prime ministers from countries both large and small. The 45,000 veterans in attendance were treated like the heroes they were.

The events surrounding the 50th anniversary of D-Day formed a year-long cottage industry in France with more than 350 events, ranging from a Second World War themed jazz festival to the construction of three new major military museums. The 50th anniversary tide of historical memory had arguably begun to swell the year before with the 1993 release of Steven Ambrose’s Band of Brothers. And the 1994 ceremonies, as it turned out, represented only the leading edges of the Second World War wave that struck America’s collective consciousness. The full force of the wave did not crash ashore until the 1998 release of the Steven Spielberg movie Saving Private Ryan and the publication of Tom Brokaw’s The Greatest Generation. Next followed Tom Hanks’ and Steven Spielberg’s collaborative effort on the HBO miniseries adaptation of Band of Brothers in 2001. The tide of remembrance receded only slowly, marked by the opening of the National World War II Memorial in 2004.

April 2017 marks another watershed moment in America’s military history – the 100th anniversary of the entry of the United States into the cataclysm that was the First World War. Much as the famous Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial sits atop Omaha Beach at Colleville-sur-Mere and stands as silent witness to the brutality of war, the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial sits near Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, keeping silent vigil over a landscape that had once been cut by trenches during the carnage of the final stages of the First World War. While the Normandy American Cemetery, with its nearly 10,000 crosses, still hosts throngs of visitors and pilgrims every day, the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, with its nearly 15,000 crosses, lies almost silent as only a tiny trickle of visitors pause to honour the fallen.

The Second World War transformed the United States and the world in myriad ways. Within that historical avalanche of events, the campaign in Normandy stands alongside Stalingrad, El Alamein, Kursk, Midway, Guadalcanal and many others as a pivotal moment. Certainly Normandy, and the titanic war of which it is a part, is deserving of historical fame. But in many ways the American experience in the First World War was even more transformative.

It was with its declaration of war in April 1917 that America first took its place on the world stage, a place it has never relinquished. It was in the First World War that America came of age, muscling its way to the international table to sit beside its European and Asian rivals. It was the beginning of what many historians now term the ‘American century’. There is now a widely accepted school of thought that views the First World War and the Second World War as integral parts of the same conflict. In that view the Second World War, for all of its ferocity and carnage, merely continued and propelled forward changes that had their beginnings in the First World War.

The First World War was, perhaps, the most important single event, or series of events, of modern times. Within that war, the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne stands out as the pivotal American moment. Led by General John ‘Black Jack’ Pershing, the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) sought to expel the Germans from a vital sector of their Hindenburg line of defences. The battle, involving over 1 million American military personnel, raged from 26 September until the end of the conflict on 11 November 1918. After bogging down amidst the formidable German defences and suffering from critical logistics breakdowns, the American forces eventually made great gains – but at a tremendous cost. More than 26,000 US soldiers were killed and over 110,000 were wounded, making the Meuse-Argonne far and away the most costly battle in terms of lives lost in American history.

Given the importance of the conflict, the intensity of the fighting and the tragic losses incurred, the history of the First World War in the United States is sadly obscure and intellectually incomplete. A trip to any major bookshop will reveal shelf after shelf of books on all aspects of the Second World War, while the few books on the First World War languish in a small, dusty corner. Americans remain fascinated by the towering personalities of the Second World War and find the First World War to be oddly unsatisfying. Perhaps it is because the First World War was such a slow-moving affair that resulted in such a short-lived and ill-advised peace. Set against the evil of Hitler, the menace of Stalin, and the stubborn resolve of Churchill, the leaders of the First World War, men like David Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson, seem stodgy and in over their collective heads. Perhaps some of the problem lies in the communications technologies of the time. The Second World War can be experienced in sharp film images, some of which are even in colour. First World War images, though, are herky-jerky and mute.

Europeans and their historians take rather more note of the First World War, where it is often still termed the Great War. The heightened public and historical awareness of the events of 1914–18 across the pond is in part because the conflict had such an outsized effect on the course of Europe’s collective future. The Great War shook the foundations of Europe that had been centuries in the making, shattering the Russian Empire, destroying what had been the Austrian Empire, leaving embittered nations in Germany and Italy that were susceptible to the rise of dictatorial regimes, weakening France, and crushing the Liberal Party in Great Britain.

The historiography surrounding the Great War in Europe has followed an interesting pattern. First there was a great flood of books published mainly by the wartime participants themselves, taking credit for successes and laying blame for failures in the largest single series of events that the world had ever seen. After the coming and going of the Second World War, the study of the Great War fell out of favour with the few historians remaining, labelling the earlier conflict futile, its participants bumbling and its tale less than compelling.

As the Cold War frightened the modern world, the Great War seemed ever more antiquated and less worthy of historical attention, other than damning its leaders as hidebound and uncaring. Only in recent years, with the complete opening of document collections and archives, has the study of the Great War undergone something of a mini renaissance. Without societal axes to grind, modern scholars have shone a much more careful light on the events of the first two decades of the twentieth century and have utilised methodologies varying from gender history to cultural studies to advance our understanding of the First World War. Sadly, although the Great War is at last something of a B list celebrity in Europe, there has been no corresponding rise in prominence on the US side of the Atlantic. There is a small group of American historians toiling away on research concerning the First World War, from Michael Neiberg to Mark Grotelueschen, but their numbers pale in comparison to the army of US historians who work on the Second World War.

What makes the situation all the more difficult to understand is the remarkable literacy of the First World War. Almost all of the untold millions of officers and men who took part in the conflict could read and write, and many were inveterate correspondents, diarists and poets. From Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig’s diary, which lays bare the mind of a strategist, to collections of vivid letters penned by humble enlisted men and sent home to loved ones, the vast archive of written source material on the First World War is a historian’s dream. Researchers can access the treasure trove of historical raw material at archives big and small, from the US National Archives to dusty and seldom used local collections in France and Germany.

The new work being done on the First World War in the US and Europe is fascinating and in many ways represents history at its best. The focus of that work, though, tends towards the strategic. Was the war futile? Were the commanders of the First World War innovative, or stagnant in their thinking and actions? Was the war a true international turning point? While questions such as these are certainly worth a good historical pondering, the lowest levels of conflict have received even less reconsideration. What was the Great War really like for its young practitioners? Why did young men go to war, and how did violent combat interact with their humanity?

In the immediate aftermath of the First World War several veterans of the conflict penned testaments to their experiences that still stand as classics of the genre, including Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, Frederic Manning’s The Middle Parts of Fortune and Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer. Since those early days, though, too few writers have turned their pens to the real, gut-level experience of the war. For the laundry list of reasons catalogued above, the First World War from the standpoint of the regular soldier remains something of a historical unknown. And the case is even worse regarding the lives and times of United States soldiers. Other than the famous few, the historical anomalies like Sergeant Alvin York, the US serviceman toiling for his country in the American Expeditionary Force at St Mihiel or the Meuse-Argonne remains, sadly, historically anonymous.

Patrick Gregory and Elizabeth Nurser’s An American on the Western Front marks an important first step to fill the historiographical lacuna of the experience of American soldiers fighting and dying in the trenches of France. The study is based on the extensive letter collection of Arthur ‘Clifford’ Kimber, uncle of Elizabeth Nurser, an early volunteer, an avid correspondent and a true man of his time. Blended with a deft editing hand of historical background, Kimber’s wonderfully written letters make for compelling reading. Gregory’s narrative history is detailed, accurate and well written, but it is the letters themselves that really set this study apart and make it so indispensable for both laymen and field experts alike.

Through Kimber’s many letters, readers are able to access the human level of war – the essential humanity of a young Californian with great dreams, thrown into a maelstrom of events that would eventually take his life. Kimber’s letters are full of texture and nuance, ranging from wondering about his life’s goals, to meetings with the famous and near famous, and efforts to spark and receive love. Here we see the full picture of an American Great War soldier – from his pre-war decision to enter the military, to train journeys across the country with his mother, to his petty squabbles with friends, to his decisions to join the flying corps, to the nearly endless boredom and to questions of his eventual mortality. Here we see war as it really was rather than the type of war that we so often read about.

An American on the Western Front forms a compelling story that allows modern readers to access the First World War for what it really was – a war fought by young men with real lives and dreams. A war of puffing locomotives, boundless patriotism, scheming officers, bad food, fleeting glimpses of love, personal foibles, rivalries great and small, distant families, endless boredom and training and eruptions of death and destruction. This work by Patrick Gregory and Elizabeth Nurser allows us all a fascinating window to a dimly understood past – a past that has lain historically dormant for too long.

Professor Andrew Wiest

1

BANTHEVILLE,OCTOBER 1920

The farmer posed proudly in his tractor, staring out over the freshly dug earth at the two Americans. The men were both grimy and sweating from their exertions in digging the heavy, debris-laden mud. It had been a long day for them, only partially successful, and the light was beginning to fade. The farmer hadn’t used his tractor to help them – it was too delicate a process for that, he knew – but he’d been on hand to advise and encourage them nonetheless, to help them move some of the heavier earth. Now, at his request, one of the men was taking his picture. A memento, perhaps, of a successful day yet to come, a day when the man with the camera might find his brother.

George Kimber had only recently arrived in Europe, the first time on a continent he hadn’t quite made it to as a 10-year-old boy. But this was different. Then, a family holiday in England, after a year’s schooling for his elder brothers in Canterbury, had ended with John and Clifford having an extended adventure with their father in mainland Europe, while young George had accompanied his mother back to Brooklyn. But now here he was, back in his own right, in Europe to study. A botanist by training, he had taken up the offer of a scholarship at the University of Brussels, the guest of an organisation which was a hangover of the recent war in Europe, the Commission for the Relief of Belgium. His work under Professor Rutot was as enlightening as it was challenging: he was enjoying his time, enjoying the rigours of the study; and he liked Brussels and Belgium.

But he wasn’t in Belgium today. He was standing in what once had been a garden, now strewn with rubble and weeds, in a small village in north-eastern France; and the reason he was there had nothing to do with botany, with the possible exception of the tangle of weeds beneath his feet. Part of what had brought him to Europe in the first place, and this village in particular, was unfinished business with one of his brothers. It wasn’t about his regrets at not accompanying him when he was a boy: this time it was to find his body. Because Clifford had not just travelled to Europe once without him: he had gone back again as a young man in the service of his country, and that second time he hadn’t returned. His big brother was frozen in time as a 22 year old, just George’s age now.

The village of Bantheville and its surroundings were still recovering from the war: the evidence of the war’s ravages was still around and about. Two years on, give or take a few weeks, and its after-affects were still to be seen and touched, the detritus under his feet and some remaining mementoes in the ground which sloped above him up to the churchyard, twisted metal reminders of a conflict which had claimed so many. The many in this area had included local French men and women, of course. It also included the German battery which had operated from the village, and it also numbered the young American pilot who had tried to silence the battery.

It had been the opening day of an offensive in this Romagne area of north-eastern France, part of a wider Franco-American push to break the resolve of the German forces here at the end of September 1918. Arthur ‘Clifford’ Kimber had been sent in sometime after 11 o’clock on that misty morning, following the line of the road up from Grandpré to Dun-sur-Meuse. At Bantheville, focusing in on a target on the ground, Clifford had begun to dive. But artillery fire from the ground caught him, his plane exploded, stopping him forever, the wreckage plunging down to the ground and the village.

George remembered the letter his family had received at the time from Cliff’s commanding officer. ‘He was an excellent flier’, Captain Ray Claflin Bridgman had said, ‘made a good record while with the squadron and gave his life for a noble cause’. But what ate at George was the fact that his brother’s body had never been recovered – and there was an actual body, he was sure of that. A body which had been buried, and somewhere here; he had ascertained as much from various sources. But the question was, where? There was no concrete information from the various sources he had contacted as to where exactly a grave might be, and no obvious clue on the ground here, no marker certainly, and in terms of intelligence only conjecture from the locals. So this was a new chapter for him, trying to fit more pieces into the jigsaw of information that he and his mother had assembled over the last couple of years. Now he was digging into the earth beneath him to see if his belief could be vindicated.

Before setting out for Europe, George and his mother Clara had managed, through various intermediaries, to contact a member of Clifford’s old 22nd Aero Squadron unit, a former airman who, they had heard, might hold a clue. Lieutenant John A. Sperry had been shot down and captured by the Germans somewhere near Bantheville days before Clifford’s plane was destroyed and had seen an ID tag in the possession of a German officer – Oberleutnant Goerz – and he recognised it as Clifford’s tag. If a tag had been found, perhaps it had been recovered from a body. Also, Sperry had been told, a body had been recovered and buried somewhere nearby. Armed with these snippets, and once settled in Brussels in the autumn of 1920, George had written to the German authorities in Berlin. But the information he had received back from the Deutsche Militär Kommission – a numeric list answering his various queries – had been dispiriting:

There was no information available on his query from the German Central Records Office in Berlin.

The warden of Bantheville cemetery says there is no grave there belonging to Arthur Clifford Kimber.

Oberleutnant Goerz has no information. He burned records after the war.

Re: the shooting down of Clifford’s plane – It has been ascertained that a Spad plane was brought down by the anti-aircraft battery no. 721 in the western section of the Meuse, behind the German lines, on September 26th, 1918, according to a notice contained in the war diary of the Commander of the Anti-Aircraft of the 5th German Army. As the aforesaid battery had taken up position in the vicinity of Bantheville at the time when the Spad airplane was shot down, it is supposed that this plane was that of the 1st Lt. A.C. Kimber.

So George now found himself in Bantheville in the fading light of an October day. He had to determine for himself what the parameters he was searching within were, what the area looked like, where the obvious places to look might be, how many clearly unmarked graves there were to contend with. He needed to see who might give him some clues, to ask locals what they remembered. Before he set out from Brussels he had written ahead to the local authorities at the American Graves Registration Service who, since the war, had been assembling the nearby American Cemetery at Romagne-sous-Montfaucon. He asked if anyone might help him search and, also, if they could recommend anywhere to stay nearby. They had replied promptly, assuring him that someone would be on hand to assist him when he arrived and that rooms were available in the Hostess House of their local YWCA. So George had set out, travelling, as was his wont, with two suitcases, one full and one empty, the latter to be filled in the course of his travels with dirty clothes.

The man from the cemetery delegated to help him was Captain Chester Staten and, after making contact with him at Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, the two set out towards Bantheville. A quick inspection of the graveyard of the church there bore out what George had already been told: there were no plots bearing the name of Kimber. So they began chatting to some of the locals: what did they know? Did they have any leads or suggestions? Rather curiously, the first thing they discovered was that they weren’t the first Americans to visit the village recently looking for a body. An American officer had come from Germany, from Halle, to look for the body of a fellow serviceman, an American lieutenant, an aviator. The officer had been looking, on the locals’ suggestion, in the very area George now stood – the garden between the church and the road.

The officer, whoever he was, had apparently found nothing when he looked. That didn’t deter George: he wanted to do his own searching and his own digging. George and Captain Staten got to work with spades, turning over the ground as carefully as the soil would allow and throwing rocks and debris to one side. It was hard going. The ground was heavy and frosty and after several hours of labour their work showed only glimmers of hope. Human remains were there all right, and even then, not one but two bodies, but these were not their fellow countrymen: they were the bodies of two German soldiers, possibly simply buried in the ground where they had fallen two years before. The two men decided to suspend their dig for the time being, mindful that in turning over this lumpy ground they might be disturbing and cutting through more bodies – German, American or French – than they were uncovering. ‘It was best not to work over the garden too thoroughly,’ George wrote later in a letter to his mother, ‘for fear of obliterating all traces of graves, until we have more definite information.’ They decided to wait some months until springtime when, it was hoped, the ground would be more friable and easily sifted.

But their earlier search of the ground up near the church had proved more fruitful. Among the detritus of metal and other tangled remains left over from the war, they managed to uncover – rather surprisingly, given that it was now two years since the war had ended – the parts of two aircraft, including the two engines. The wreckage of the first was above ground, the second partly buried in the soil. Carefully removing a marker containing a number from the first, Staten then dug down into the earth to see if he could find any clue as to the make and origin of the second, eventually retrieving a metal plate with a serial number. These could, George hoped, prove to be vital clues.

2

LETTER-WRITING

29 October 1920

Back in Brussels, George wrote to the Headquarters of the American Forces in Germany in Koblenz, reporting on what he had pieced together thus far. Could they, stationed in Germany, uncover more information on Clifford from German records? It had been a German garrison after all, so could those records provide a clue as to who might be buried there, and where? He said he had heard of several cases of new records being found in the German war offices, apparently previously overlooked, concerning the graves of Allied soldiers who had been buried by the Germans. He had been told as much at the cemetery in Romagne and on a recent visit to Paris.

He also asked the Koblenz office for information about the officer who had preceded him to Bantheville, the one from the American base in Halle. Whose grave was he searching for? Where had he obtained information that there was the grave of an aviator? George told them he was certain that Clifford’s body was somewhere to be found in the village. He had the word of the Red Cross for that: they had stated ‘definitively’ to that effect in a letter to him two years previously. He and Captain Staten had also now found plane wreckage at Bantheville which he thought could be Clifford’s; and there was that third piece of information to go on – the testimony of Lieutenant Sperry.

In terms of possible locations the area to concentrate on, he told them, in a phrase he was to find himself writing time and time again over the next year, was the patch of garden or grassland between the road and the church in the village. He wanted to leave them in no doubt about that: that was the area to be concentrated on, where a thorough search must be undertaken. Yet in private correspondence home he was more muted, conceding that his conviction was based more on a balance of probabilities: ‘From the stories told me by the peasants [locals in Bantheville] who, unfortunately, are not always in accord, and from the more positive information I have regarding the circumstances of my brother’s death, I am inclined to believe that his grave is in the garden.’

23 November 1920

George wrote to his collaborator in the search in Bantheville, Captain Staten, at Romagne-sous-Montfaucon. He had another piece of information for him to pass on to his Graves Registration Service colleagues there. George had written to his mother in Palo Alto back in California to check on a letter she had received eighteen months before. The Adjutant General’s Office at the War Department in Washington had written to her then with some details of how Clifford’s plane had been shot down, and the letter had contained some technical specifications of the plane he had been flying: a Spad XIII (pursuit plane), number 15268, engine (Hispano-Suiza) number 35529.

George was excited. The number tallied with what they found. George wrote:

It seems therefore that the airplane which you and I concluded last month was my brother’s, the one from which you took the plate near the church at Bantheville, was, in fact, my brother’s machine. I think that we may assume for the present, in the absence of any information to the contrary, that the grave in the garden, between the church and the road, if there be the grave of an aviator in the garden, is my brother’s.

He also mentioned, in case a body was uncovered, that by way of possible identification Clifford normally carried around a leather pocket chessboard.

George asked Staten if he had managed to do any more searching in the meantime. ‘As one of the peasants was so positive that the grave was in a certain location, although digging there at the time did not seem to promise very much, have you looked into that location further?’ He also enclosed the photograph he had taken of the farmer in his tractor and developed back in Brussels. Could Staten find his way to leave it for the farmer in the local café in Bantheville? A little ‘thank you’ for his time.

24 November 1920

To be on the safe side, he followed up his letter to Staten with another one to the head office of the American Graves Registration Service in Paris. He told them about Sperry’s confirmation of the ID tag and the fact that locals in the village believed an aviator was buried in the garden. This belief – or was it speculation? – may have been further heightened by the recent appearance of the unnamed officer from Halle. He had been specifically looking for the grave of an aviator in that patch of grassland. How many aviators had been removed from the locations around Bantheville to the Romagne cemetery? Also, did they know who the Halle officer had been – a Graves Registration Service person? Why had he gone and why did he think there was likely to be a grave there?

30 November 1920

For good measure, George also wrote to the adjutant general and the Chief of the Air Service in Washington, giving information on his searches thus far and requesting information on the officer from Halle who had visited Bantheville. Where had he got his information from?

Something occurred to George, a name he remembered from the past: an officer in the American Air Service, a Captain Fred Zinn who had written to his mother some eighteen months before. Zinn had passed on information he had obtained from the German authorities at the time, some of which had since been restated to George in letters from Berlin. Was Zinn the officer from Halle? George also gave the Air Service command the engine numbers on the remains of the two planes he and Staten had found.

2 December 1920

A rather flat response arrived from the American Graves Registration Service in Paris two days later, one of many such messages George would get used to receiving over the months ahead. This was perhaps a reply to both his letter to them and the one he had sent to the HQ of the American Forces in Germany at Koblenz – maybe Koblenz had forwarded his letter to Paris. The Graves Registration letter was brief and to the point. There was ‘no further evidence’ of burial and ‘no further information’ had been received from German authorities.

The weeks passed by, and in the absence of any further correspondence from authorities in Germany or France or the United States George concentrated instead on his studies. It was approaching Christmas and he had been invited by a friend, a fellow botany student in Brussels, to spend the holiday period in Switzerland with his family. Fernand Chodat knew that George did not have any family in Europe and besides, he wanted George to meet his father Robert, the professor of botany in the University of Geneva and director of its alpine laboratory. In Geneva, George would also meet Fernand’s mother and three sisters, twins Isabelle and Emma, and their elder sister Lucie.

22 December 1920

But before he left on his Christmas holidays, George had time for another quick exchange of letters to and from Washington. The Chief of the Air Service’s office had written back. Information, the letter said, would be sent to him at the earliest moment. Yes, it was Captain Zinn. He had made an ‘exhaustive tour in the endeavour to locate information as to the fate of a number of missing pilots and observers’, said the letter, adding somewhat doubtfully that ‘much of his investigation was guided by hearsay and statements of local residents’. But rather more bafflingly for George, the Chief of the Air Service’s office went on to venture that it was ‘doubtful identification could be made of the planes’ that George had mentioned. As a statement it seemed a little odd. George knew that he had, at the very least, located Clifford’s plane. That much could not be gainsaid.

23 December 1920

George replied to the air chief’s office by enclosing the letter forwarded by his mother: the correspondence they had received some time before from Clifford’s colleague, Lieutenant John Sperry, setting out in more detail what had happened to him. He, Sperry, had been shot down and taken prisoner on 4 October 1918, south-east of Grandpré, not far from Bantheville. George now realised that this was some days after and not before Clifford was killed, although it changed little. Sperry went on to detail what he had witnessed after being captured by German forces. He said that he had seen Clifford’s ID tag in a German flying observer’s quarters in the town of Montmédy, behind German lines. It was in the possession of an officer called Goerz, a lieutenant from Burgfeld in Germany.

‘This office had a large collection of such tags,’ said Sperry:

as it was their business to keep an account of all American airmen shot down in that section. He [Goerz] told me that it was his intention to return all of those tags at the end of the war to the relatives or their owners. I was especially interested in it [Clifford’s ID tag] because [he] was in my squadron as you probably are aware. I was taken away from this officer shortly after and I never had an opportunity to speak with him again. I do remember, however, that he said that the body was buried but that he could not tell me just where.

George set out later that day for Switzerland with Fernand, the two young men travelling by train down to Geneva. It was an enjoyable break, a family time, and one made still happier for George by the time he managed to spend with one of Fernand’s sisters, Isabelle. Three years younger than he was, Isabelle had made an instant impression – a student in fine art at L’École des Beaux Arts de Genève. George determined to go back to see her the following summer. But in the meantime it was back to Brussels. He returned a fortnight later to his apartment in the Rue de la Loi, focused on the twin-track of his studies and the search for his brother.

7 January 1921

The first letter he received in the New Year promised little. It was another, rather bald, note from Washington, from the War Department Office of the Director of the Air Service, telling George what he knew already. ‘The records of the Berlin Central Records Office show your brother to have been killed in action September 26th 1918 and to be buried in Bantheville.’ It was hardly worth sending, he thought.

2 February 1921

A month on and George was itching to get back Bantheville to renew his search. He wrote again to the authorities at the cemetery at Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, addressing his letter to the commandant there to check what progress, if any, had been made. He thought it best to go over the details of his case once more, given the thousands of records they dealt with. ‘Last October when Capt Staten and I were searching we both of us felt the strong probability that the grave was in the garden between the church and the road in Bantheville.’

He explained again how the two of them had decided that to have conducted a more thorough search back in October, given the condition of the ground, would have risked ‘obliterating all trace’ of a body or bodies. Better to leave until February, by which time ‘the grass and weed covering had been beaten down by rain, wind etc., thus exposing the actual ground’. So now, here he was. Had Staten already begun the search again? Was Captain Staten still at the cemetery or had he been transferred to other work? Or, conjuring up another name he remembered from the previous October, what about Lieutenant Denny? George said he would like to go down to Bantheville in two weeks’ time to recommence the search. Would the Hostess House of the YWCA be open?

3 February 1921

The following day, he wrote to Dame Adelaide Livingstone at the British Embassy in Berlin: a Colonel Thomas at the American Embassy in Brussels had suggested he get in touch. He wondered if she could help with any official German war records from her position in Berlin? He said that the only information he had been able to obtain thus far from the Berlin Central Records Office (complete with a few typos of his own, and errors in the German records) was:

List 28122/W

Kimber A.C. Lieut. Flieger

Beirdigt: im Bautheville

Gem. v.d. Inspektion de Fliertrup

‘I am writing to you in the hope that you can offer some suggestions,’ wrote George. ‘I do not wish to leave a stone unturned to find the grave.’

3 February 1921

The same day he wrote – in German – to the German officer named by Sperry in his letter, asking for any information he could provide. It was addressed simply, and in the hope it might eventually find its intended recipient, to ‘Lieut. Goerz, Burgfeld, Deutschland’. It was a long shot, he knew.

4 February 1921

A day later Captain Adjutant W. E. Shipp wrote back to George from the American Cemetery in Romagne. Neither Captain Staten nor Lieutenant Denny was still there and no, the body had still not been found ‘but’, added Shipp, ‘it is believed that the present season is as favourable as any other for searching for bodies’. If George wanted to assist, a searcher would be sent out with him to Bantheville ‘and all other possible assistance will be given in this search’.

5 February 1921

Back in the US, the office of the quartermaster general of the War Department in Washington had written to his mother in Palo Alto. It might have been something or nothing – it might have been the authorities wishing to plan for the future, to have some information to hand in case something did turn up. Or, perhaps, in fact, they knew something. The person writing to her, Captain M. N. Greeley, Executive Officer of the Cemeterial Division, asked Clara if she could provide dental records for Clifford, ‘ … chart of all dental treatment … to include filling, crown, bridges etc. as well as any fracture of bones prior to entry into military service’. The information was ‘to be used in matters of identification’, although no further information was forthcoming.

7 February 1921

Adelaide Livingstone replied to George’s letter from the British Embassy in Berlin. The Americans had now established a Missing and Enquiry Unit of their own in Berlin, she said, and they would be better able to offer assistance. She suggested a name – Captain E. M. Dwyer, US Cavalry.

28 February 1921

The trip to Bantheville had yielded nothing. Back in Brussels George was trying to get on with his own work, but he was impatient with the lack of any progress in his search. He had received nothing for weeks, not since his mother had told him about the request for Clifford’s dental records. So he took to his typewriter again. Thus far he had concentrated on Americans in Washington and Americans in and around Europe; French locals in Bantheville; Germans; the Red Cross; the British, and on any sources he could muster in Belgium. Time now for the French authorities. But who to write to? He didn’t know, but in the end he decided to go to the top – to the hero of Verdun and France. Writing in French, better than his rather rusty German, he sent it to ‘Monsieur le Maréchal Pétain, 4 Boulevard des Invalides, Paris, France’. Pétain could always ignore it if he chose to, but George didn’t want to leave any stones unturned.

28 March 1921

Something and nothing – the American Forces in Germany, HQ of the 2nd Section of the General Staff, Koblenz, wrote to him, and the Central Records Office in Berlin had written to say that they were investigating and that as soon as any information was available they would be in touch.

4 April 1921

Surprisingly, a reply came from Pétain’s office in Paris, from ‘Le Maréchal de France, Vice-President du Conseil Supérieur de la Guerre’. Perhaps something had piqued the interest of the man who famously didn’t let them pass at Verdun. The letter said that Pétain had written to the general commanding the Verdun Sector to ask him to investigate the case. He said that the central administrative body in Paris now also knew of the request and would follow it up. ‘At this stage research is continuing and the Maréchal will not forget to send you on the results.’

10 May 1921

Back in California, the US Army Cemeterial Division had written once more to Clara. Captain Charles J. Wynne said that a search party had gone back to Bantheville armed with a sketch that George had provided them of the village. The party found the area George had searched but merely concluded that ‘the area was covered by stone and debris: although locals said it had been a garden prior to the German departure and was only covered over after. Either way, no body was found.’ Captain Wynne suggested that perhaps Clifford’s body had been brought, unrecorded, to the Romagne-sous-Montfaucon Cemetery nearby as an unknown, though searches would continue. ‘The spot indicated on [George’s] sketch as the location of your son’s machine is inaccurate. The machine was found about 150 yards north-east of the spot and was buried in the ground’.

George seemed further away than ever from unravelling the tangle.

3

COMING OF AGE

The young Arthur Clifford Kimber had only been in California for five years when he went to Stanford University in September 1914. He was following in the footsteps of his elder brother John and looked to the experience as yet another in an already long list of adventures they had had together. He began to find his way around the college campus and enrol for classes but, as he did so in this happy and positive environment, the first battles of a savage war were already being waged 6,000 miles away in Europe, a war in which he would later become involved.

The conflict was, in all senses, a world away from the one Clifford, as he was known to his family, enjoyed in the sunshine of Palo Alto. The family had moved west when his father, the first Arthur Clifford, a clergyman, had died suddenly in the summer of 1909 in the apartment above the church he had established in New York. It had been a terrible loss for a still young family: for his widow Clara, at 42 more than twenty years Arthur’s junior; for the eldest boy John, who was 14 years; and for Clifford, 13, and George, two years younger.

Reverend Arthur Kimber. (The Days of My Life, © Kimber Literary Estate)

Sketch of St Augustine’s church, New York, around 1880. (The Days of My Life, © Kimber Literary Estate)

The Reverend Kimber had been a dynamic and inspiring figure, not just to the family who looked to him as a guide and for love and support, but to a large body of parishioners in downtown New York. Thousands of men and women, many of them recent arrivals to the United States, flocked to his mission church in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. He was the vicar of St Augustine’s, an Episcopal church in the city’s Bowery area: an area which acted as a magnet for the city’s dispossessed or newly hopeful. St Augustine’s offered spiritual, and some practical, support on the way. A devout man, he passionately believed that his Anglican tradition constituted a modern manifestation of the true church of the apostles, and through it he wanted to do what he could to help the people who came his way.

The mission was an offshoot of Trinity church, Manhattan, located on Broadway and Wall Street, the main Episcopal church of New York and the wealthiest parish in the United States. Trinity church had served the area since the late seventeenth century, a place of worship for some of the city’s celebrated figures over the years, and at the time of Kimber’s ministry the Sunday home of many powerful and rich New Yorkers, including members of the Astor family.