7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Garnet Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

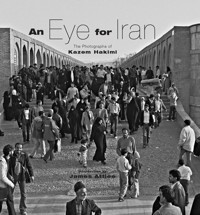

Through his use of conventional black-and-white film and a belief that a good photograph is the result of constantly watching to predict the perfect moment, Kazem Hakimi's work harks straight back to the photojournalism of Cartier-Bresson and those early Magnum photographers who were able to capture moments that superficially contained nothing, but which when printed onto photographic paper became iconic images. With the United States and Iran once again squaring up to each other in the Persian Gulf and the actions of firebrand president Ahmadinejad never far from the news, "An Eye for Iran" provides a welcome opportunity to view images that show the human side of a nation we are being led to distrust.Here and there someone spies the lens as the shutter opens, but the drift of Iranian society is caught in the postures of the everyday: human faces in the streets, relaxing in the parks, the glimpse of designer clothes under a chador, pride in a motorcycle, a young couple enjoying a game of chess...Throughout, Hakimi shows how well he understands the techniques of traditional photojournalism: he remains both present but still invisible to the people in the scenes his lens has captured. The result is a captivating book that will appeal to all those wishing to gain an insight into life in this unique and fascinating country.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Ähnliche

An Eye for Iran

The Photographs of Kazem Hakimi

.

Introduction by James Attlee

GARNET PUBLISHING

For my beloved spiritual master Grand Sheikh Mohammad Nazim Adil Al-Qubrusi, who has always blessed me with his endless spirituality; and to my dear wife Carolyn for being the most wonderful wife and the backbone of my family.

INTRODUCTION

A man at the latter end of middle age (although his age is unimportant) strolls down a leafy boulevard, unaccompanied except for his own shadow. Dressed in a baggy suit that could date from the 1940s rather than the 21st century, with a hat crammed down on his head, he is walking ahead of the photographer, his hands clasped behind his back. There is something at once casual and purposeful about his stride as he progresses into the middle distance, a direction our eyes are led in by a seemingly endless string of light bulbs that hangs between the lamp posts above his head. At the moment the photographer has captured, a puff of wind gently inflates his jacket and he turns his face to his left so that we see him in profile, his expression neither happy nor sad, simply observant.

This is not a photograph for those who are looking for action, narrative or high drama. I first saw it on the wall in an exhibition. Two weeks later, when I happened to run into the photographer, it was still fresh in my mind. I described it to him: the one of the man in the suit walking who turns his head, just as the wind catches out his jacket? Kazem Hakimi grew animated, as photographers tend to do when they discuss their work. “Yes, yes,” he said, “I had to walk behind him for fifteen minutes before that happened. Did you notice how his jacket and the plant pot are the same shape?”

I wasn’t sure I had noticed, so I returned to the image once more. Sure enough, the stroller, the flâneur if you will, is approaching a concrete planter in the middle of the pavement that looks like a flying saucer, or the mouth of a lily. The man’s jacket, flaring out at the waist, is an inversion of the shape, like a bell. The photographer, stalking the solitary figure ahead of him, has waited for this instant, when the action of the wind and the congruence of physical appearances all come together, and he can press the shutter. This moment, when nothing much happens, is nevertheless a well in which we can immerse ourselves again and again, an intensely experienced fragment of the present.

It is a very European photograph; or at least, it is very much in a European and American tradition of street photography, both in its subject and in the process of its creation – the photographer stalking his, or her, prey, waiting for that moment to arrive in which chance and expectations collide. Even the technology used – black-and-white film loaded into a Canon SLR – is little changed from the first half of the twentieth century. The shadows cast by the trees on the pavement are a motif familiar in dozens of works from the period. The man’s clothes are timeless; the streets either side of the pavement are eerily empty of traffic.The photographer has somehow achieved invisibility, able to freeze a moment on film without interrupting the flow of the late afternoon. Yet we are not in Paris or New York, but Isfahan; we know the photograph was taken in 2004. Has the camera become a time machine, transporting us back to an earlier age? Or, indeed, a method of translating for us a foreign scene into a language we understand, letting us breathe the atmosphere of a sidewalk few of us will ever visit, in a country more often represented in the hyperbole of politicians’ speeches? We must ask ourselves, as we have to when looking at any photographic image, who is the photographer and where do they stand in relation to what they are photographing?