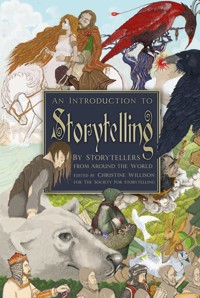

An Introduction to Storytelling E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Where do stories come from, and how do we come to know them? Daughters listen with wonder to their grandmothers' tales. Journalists have their trusted sources. Writers of storybooks draw unconsciously from the works of their predecessors. It is as if every story has within it an infallible truth, contained in the echo of its original telling. The storyteller recounts the tale. The listener hears, learns and remembers. In due course they will retell the same tale, adding in something of their own. And so listeners in time turn into storytellers. This inspiring book brings together the stories from across the world of listeners who themselves became storytellers. They reveal who influenced them the most, what drew them further in, what they learnt, and what they now wish to share with new generations. Tips, tools and tales: read this book, and take your turn.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 309

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Christine Willison, 2018

The right of Christine Willison to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8858 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Great Britain

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

An Introduction to Storytelling

To Begin

Finding Your Own Route John Row

Stepping Stones Kevin Crossley-Holland

Taking Charge of our Lives through Storytelling: A Memoir Jack Zipes

Gathering at the Well Taffy Thomas, MBE

Word Magic Hugh Lupton

Telling the Mabinogi Michael Harvey

Storytelling for the Very Young Anne E. Stewart

From Talebones Tony Cooper

All the better to hear you with: Tips, Theory and Proof for the Educational Benefits of Storytelling Chip Colquhoun

My Journey into Storytelling Pete Castle

Honest Liars: A Challenge for Our Times Michael Wilson

From Pen to Tongue Deb Winter

Blooming Flowers and Stony Stares: Negotiating Identity through Story Emily Underwood-Lee

Still Sorting the Sock Drawer: The Ever-Changing Story of a Life-Changing Diagnosis Eirwen Malin

Finding my Jewish Stories Liz Berg

Kamishibai in Australia Jackie Kerin

Born of this Land Anne E. Stewart

From the Alps Klara Miller-Fuhren

Using Storytelling to Teach Special Needs Students Gary and Linda Kuntz

Sharing Stories, Sharing Understanding: Learning Language through Story Eirwen Malin

Storytelling to Enable Language Christine Willison

‘Speaking in Tongues’: Telling Stories in Languages Other than One’s Mother Tongue Fiona Collins

Think in the Long Way Uncle Larry Walsh

Cath and Ramy Share Stories Cath Little and Ramy

The Travelling Storyteller From Sam Allo’s Blog

The Storytellers

This is a collection of anecdotes, experiences, explanations and suggestions from storytellers around the world, covering many topics, styles and approaches. From these varied journeys into storytelling, you will see that there are as many avenues into the art form as there are stories within it. So, this is not a ‘how to’ book, but more of a ‘ways of doing it’ book. We include storytelling in health, in schools, with people in special needs education, with young children, and in support of language learning. We give hints and tips on style and content. We explore where storytelling sits between truth and lies. Here you will find both practical advice and philosophical insight. Most importantly, we want to engender the love of stories and the fun that can be had. All contributors have agreed to donate any royalties to the Society for Storytelling (www.sfs.org.uk). We thank them all.

Christine WillisonPembrokeshire, 2018

What do we mean by storytelling? It’s a term used by writers, film-makers, journalists, actors, puppeteers, poets, readers and others who use story in their art.

All of these are valid, but the Cinderella of the art form is the traditional oral storyteller. No script, no props, no cameras, no books, no pen or paper are required. Just a comfy place to sit and a glass of water and the magic of ‘Once Upon a Time…’

Starters

My advice on beginning is to start safe, with your own family or friends, maybe a class in your local school. Children can be your best starting point. You can tell small people the same story every day for several weeks. They love it, feel secure in the familiarity of a known story. You will have time to get to know the story inside out and upside down. It’s amazing how much you can discover from a story told repetitively.

Why?

Why do you want to be a storyteller? You may want to tell stories to your family, to recreate a family story, a piece of local history, retell a myth or legend, or revive a childhood story. You may have an occasion like a wedding, funeral, naming ceremony or anniversary coming up at which you would like to tell a story. For some people it’s therapy or a form of catharsis. For others it’s a way of combatting loneliness, old age or shyness. You may simply want to share something you’ve heard with an audience or group of friends. There is no right or wrong, but there must be enthusiasm and passion.

Telling Professionally

When you embark on your career as a storyteller, or even if you need to brush up your skills mid-career, most professionals would advise you to look at going on a course. There are some good centres which can provide useful tuition. It is also good to engage with others since storytelling can be quite a lonely occupation. In addition, you could join the Society for Storytelling, who have edited this book, or Cybermouth, the Bleddfa Centre in Wales, Halsway Manor and other relevant societies/places. Many parts of the UK and around the world have storytelling clubs, where you can meet in a friendly non-threatening environment and try out your new skills or air a new story.

Arm yourself with a library of books (see my suggested reading at the end of this chapter). Be prepared to translate these texts into the totally different form of oral storytelling. This can take a long time. I have stories in my own repertoire that I have been telling since the 1980s, but I still find new ways, voices, additions and refinements each time I tell them.

Be shameless. When you hear a good story, well told, use it. Not verbatim, obviously, but take away the bare bones and add yourself into the story by working and working at it. The only exceptions I would mention are stories you may hear from native Americans and Aboriginal Australians. I remember Uncle Larry Walsh telling a story in Footscray Arts Centre in Victoria, when a member of the audience asked if she could use the story. His robust retort was, ‘We have had our land stolen, our children stolen, please don’t steal our stories.’ So please respect sensitivities, and ask. I remember too someone phoning to congratulate me on the publication of my book Pembrokeshire Folk Tales (The History Press) and asking if she could use some of them as told stories. I explained that these were stories which belong to all of us, so please feel free, but please credit your source, which was readily agreed.

Most storytellers will refine and adapt a story over years until they have a performance/sharing of which they are proud and can truly call their own. But don’t let that put you off. The refining process can happen through performance and through workshops and sessions in schools.

Do not fall into the trap of scripting and retelling. Whilst you may be pleased with the result, it can also ensnare you. The joy of the oral tradition is the two-way process. The eye contact with your audience. You know if they are with you by the look in their eyes or, alternatively, if they are not with you because they are fidgeting, making trips to the loo or looking out of the window. A good storyteller will adapt their language to ensure the engagement of their audience; this is not possible if the performance is conforming to a script.

In theatres, storytellers like to tell with the house lights up so that they can engage with their audiences.

How Did We Get Here?

I will firstly tell my own story about how I got started, then other storytellers and members of the Society for Storytelling will describe their journey into this land of myth and legend. In addition, storytellers from all over the world have contributed a piece about their own brand of storytelling.

Christine’s Journey

We all come to storytelling via a different road. Mine began at the age of five. I started school in 1950. It was a difficult time for schools. Most teachers had just returned from active service in the Second World War. There was a certain amount of retraining required. As a result, our teachers were a mixture of unqualified people or elderly teachers brought out of retirement. We knew that the old woman who taught us in the mornings would, if we kept very quiet, fall asleep. So, we crept around and talked in whispers until we heard snoring coming from her chair in the corner of the room. Then we knew we were safe to tell stories. My stories were mostly about fairies and magic, whilst Ronnie McQuinn’s all seemed to involve wild animals. We had to keep him until last because eventually the roaring of lions and tigers woke up our teacher. I wonder what happened to Ronnie?

Whilst these stories were childlike and not memorable, I learnt some useful techniques about the uses of voice and silence and reading your audience, which I still employ.

I took up the art again when I became a mother, with three small children under the age of five.

When my own children were all at school, I volunteered as a classroom helper, listening to children reading, sharing some of my skills as an artist. I discovered that one of the main barriers to reading was unfamiliarity with books. Many children didn’t see their parents read, didn’t join the library and didn’t have any reading material at home. Where I lived in rural East Anglia, there were marvellous bookshops in Norwich and Ipswich, but these were not really accessible to many young people. I decided to create a travelling bookshop. I managed to persuade the literature officer of my local arts association to facilitate a grant. The climate for arts funding such a project was healthy. I got a youth employment project interested in doing some practical work, and we converted a caravan. I bought a towing vehicle, opened accounts with book publishers and wholesalers, and booked appointments in schools in the (then) six counties of East Anglia. I also raised funds from the Arts Council of Great Britain (as it was then) and the Gulbenkian Foundation. Everyone could see the value of this not-for-profit ‘community’ bookshop (profits on books were applied to the running costs).

For seven years I drove my Ford Cortina towing a Sprite Caravan, suitably painted with reproductions of Brian Froud’s wonderful goblins (thanks again Brian for permission) into the school playgrounds of East Anglia. I went into each classroom and in these sessions with children I helped them to understand the business of writing, publishing, selling and buying books.

We looked at the book as an object, at the elements of the book, at the précis on the back as an aid to making a choice, at the ISBN which helps to trace a book in libraries and bookshops, and at information about pricing, and why prices in the US, South Africa and Australia are sometimes included.

We talked about the writers of books, about the writing process, submission to publishers, the rejection slips which usually outnumber acceptance letters.

I introduced them to new authors and new books by their favourite writers; supporting even the most reticent reader with advice, suggestions, readings and storytelling; encouraging the sharing of oral stories with people who shied away from the written word.

Then each class had time to browse and buy. Parents came after school to share the experience and do their own browsing and buying. It was very successful.

A favourite piece of feedback was the girl who, unable to buy anything through lack of money on my first visit to her school, got a paper round and saved all her wages to spend when I repeated my visit to her school.

Arts funding then started to feel the pinch, with less money available, and certainly no funds for capital projects such as replacing the, by now, ailing caravan and tow vehicle. So I changed direction. I still visited schools, still did book sessions, including readings and storytelling, but now I set up small bookshops in each of the schools I visited.

Other publishers/organisations emulated Bookbug. Some headteachers were seduced by ‘profits’, by donations of free books and cash to the school library. Time for another change.

I now devoted myself to full-time storytelling. What joy to visit schools, arts centres, museums and festivals, requiring only a chair and a glass of water (no caravan load of books) – together with, most importantly, a head full of stories.

Storytelling is an ancient art. Before music (although of course storytelling has a music all of its own), before the sharing of images, before dance, there were stories. All you need is a teller and a listener. Preferably a fire, a comfy seat and fellow listeners, but most of all a teller who knows you, has a notion of your experiences, your grasp of language and imagery, and has a good story to tell. You will notice that a good storyteller shares a story differently with each audience depending on the look in your eyes and the inspiration which emanates from you.

An example from my repertoire is ‘The Singing Ringing Tree’, which I have been telling for over thirty years. I relish the tale for its anarchy, the tantrums of that dreadful princess, modelled on those of my oldest daughter (the one with the red hair!), its imagery, which I set in our ancient woodland here in Wales, and the transformation of the princess through survival tactics. I discover something new about this tale every time I tell it. Recently my partner and I have created a version of this tale with piano accompaniment. It’s quite a challenge for a pianist to gather prompts for music from the impromptu style of the oral tradition.

Themes and Elements

Before I hand on the baton to the other storytellers, I will mention themes. They help the memory cells to order a story.

Firstly, of course, I don’t need to tell you that a good story should have a beginning, a middle and an end. Sometimes these are the most difficult things to refine (especially the end, in my experience). You need a character. There is usually a mission, journey or problem to solve. Then no matter how much you try to avoid it, you will include the four elements of Earth, Wind (Air), Fire and Water.

Earth can be a forest, a mountain, five magic beans, a house of straw, one of sticks and another of bricks – all from the earth.

Wind often blows wisdom, messages, a storm on land or at sea. Wind can be the flight of a bird, dragon, person, broomstick. The huffing and puffing of a wolf come to blow the house down.

Fire is where we gather to tell stories, where we cook, it is our sentinel whilst sheltering in the woodland. It can be the sparks that fly from an angry sorcerer’s nose, the fire in the hearth at the bottom of the chimney in a brother pig’s brick house.

Water Our journey may take us over the sea, across the river, maidens may appear from a lake or pond. Water may magically become ice. The Spirit of the Well can help to protect a house against the intrusion of twelve witches. Water is in the pot, on the fire at the bottom of the chimney which scalds the wolf to death when he climbs down the chimney.

So, our hero may take a journey through the forest, she may meet a creature who can help her on her journey by giving, perhaps an artefact or token which enables the power of flight. When she shelters in the forest she builds a fire to keep warm and to protect from wild animals. She then has to ask a ferryman to take her across the river… and so on.

Artefacts

The following is my list of items useful in stories. I hope it will assist you to make your own list.

Key

The key could fit a door or a box. Perhaps the key fits into the lock on a box? Has the box been found in the attic, covered with dust? The box is opened to reveal… nothing or something? Maybe a map, a sword, a jewel, a book of spells, or a pair of boots.

Door or Portal

Here in Wales you need help in the search for a way through to the Otherworld. In some tales a door magically opens in the side of a mountain or in the trunk of a tree. Maybe there are three doors, the key fits only one of them and you can escape, but if you try the key in either of the other doors it’ll be the worse for you!

Box

A box is a lovely thing in a story. It may be huge – big enough to get inside, but beware if you close the lid. It may be tiny, with a magic spell inside, a magic stone, a lucky charm. Maybe the very act of opening the box sparks off some magic. It may be big enough to contain any or all of the other items on this list.

Map

Perhaps the map was inside the box? Does it show the place where treasure is buried? Does it tell where a princess is held captive? Will it help you to find the entrance to the Otherworld?

Stone

Stone soup, the sword in the stone, a stone to be rolled aside to reveal a portal or staircase going down into the darkness. A standing stone behind which to hide whilst you observe the fairies in their dance.

Sword

To guard our hero, point the way, used by a King to bestow favours, to kill the snake hiding under the rug in the bride’s room. To kill the poisonous toad blocking the flow of water into the well of life-giving water.

Pot, Crock or Jug

Ceridwen’s cauldron, the pot at the bottom of the lake hiding the princess from her rescuer, the Magic Porridge Pot, the crock of gold that every self-respecting Leprechaun has hidden somewhere.

Basket

For taking produce to market, goodies to Grandma’s house in the forest, for collecting artefacts to enable you to journey through the place of stories.

Apple

Here my dear, take an apple from my basket... the rejuvenating apples that give eternal life, the apple thrown to a wounded warrior by his guardian spirit – he takes a bite from the apple and it becomes whole again and sustains him until he is rescued.

Ring

Thanks to J.R.R. Tolkien for using this token to good effect. There is the ring that makes the wearer invisible, the inscription which takes you on the journey, the ring that can’t be removed once placed on your finger.

Trees and Forests

The Singing Ringing Tree, the forest where small girls encounter wolves, the home of the charcoal burner, the place where you visit Grandma, there will be a woodsman with the axe, a place to lose a couple of children. In days gone by, most of Europe was covered in forest, so every day your journey inevitably included time spent in the woodland.

Shoe or Boot

Cinderella’s glass slipper, Puss in Boots, slippers by the fire, the shoemaker who receives help in the night from two elves…

Loaf of Bread

The Little Red Hen after getting no help to gather grain, make flour or make bread, eats the bread herself. The miller’s sons grinding grain and heaving sacks of flour, stop work to listen to a bird singing on the roof. The mill wheel brings about the demise of the murdering woman. The loaf which, when cut, reveals more than just crumbs.

Nail

For the want of a nail the shoe was lost..., a coffin nail, a clue about horse and rider, a place to hang your coat, the bent nails and pins placed around a sacred well to ward off evil spirits.

Candlestick

The candle flame flickered… Little Nancy Etticoat in a white petticoat, the longer she stands the shorter she grows. With a candlestick in the library...

Cup or Goblet

A goblet, chalice or cup appears and reappears in stories. She held the cup to his lips... He dropped the potion into a goblet of wine… A fly fell off the overhead beam, landed in milady’s goblet. Unnoticed, she drank the contents, nine months later she bore a child...

Jewel

The search for the precious diamond. The gem which was lost from the Queen’s necklace, a precious stone set in the lid of a box.

Book

A book of spells, a book found in the attic. An inscription on the flyleaf, a note left in Chapter 13. There are many ways of using the book as a device in stories.

Finally, and most importantly – Cloth

You will know I’m sure about the relationship of stories to textiles, not just the maiden challenged to turn flax into gold, but the whole genre is interwoven with cloth, weaving, spinning, cutting, sewing.

A story is woven like cloth, it’s knitted together, a yarn is spun, its thread or line can transport and empower its audience. We embroider text with metaphor, with colour, with drama. Textiles form the warp and weft of our thoughts. The wide boy will have the whole thing sewn up. Text began as a loom of interwoven threads. Textiles provide us with tweedy, woollen, homespun, russet, describing rustic, rude or ignorant characters. In this book we have a patchwork of stories and story-related experiences.

Suggested Reading

Arnott, Kathleen African Myths and Legends, Oxford University Press, 2000

Briggs, Katherine A Dictionary of Fairy Tales, Penguin, 1993

Calvino, Italo Italian Folk Tales, Penguin, 2000

Carter, Angela The Second Virago Book of Fairy Tales, Virago, 1992

Davies, Sioned (trans.) The Mabinogion, Oxford University Press, 2008

Dean Guie, Heister (ed.) Coyote Stories, University of Nebraska Press, 1990

Opie, Iona and Peter Classic Fairy Tales, Paladin Press, 1980

Shedlock, Marie L., The Art of The Story-Teller, Dover, 2003

Squire, Charles Mythology of the Celtic People, Bracken Books, 1996

Warner, Marina Once Upon a Time, a Short History of Fairy Tale, Oxford University Press, 2014

There are loads more – please visit my website or email me on:

JOHN ROW

This storytelling business is, for me, the most exciting, rewarding and satisfying aspect of a life spent scraping a living from the arts. At the same time, it is full of frustrations.

Once bitten by the storytelling bug I became a prospector. When I was first asked to tell stories, I searched through the mountain of books in my own home to find collections of folk tales accidentally acquired from subscribing to obscure book clubs that had long since ceased to exist. As my enthusiasm grew I scoured second-hand bookshops for those prized volumes written at the turn of the twentieth century as industrialisation moved populations from the land to the city, empires collapsed and rose, and national consciousness grew in country after country and writers scurried here and there writing down scraps of stories from old men and women. I even became a collector myself, sitting in bars on the northern fringe of Europe in the early hours listening to beautiful young tourist guides who told me stories their grandmothers had told them and men who had ambitions to drive husky teams across the old reindeer routes from Lapland to Alaska.

I took every opportunity I could get to listen and get to know the giants, Hugh Lupton, Duncan Williamson and a host of others. Each teller made me realise how far I had to go on my own journey. I felt and still feel a rank amateur in comparison.

However, with the conceit of the beginner and with the need to earn a living from one artistic activity or another, I called myself a storyteller, even duplicating a leaflet calling myself ‘John Row, The Story Man’, which I had the audacity to hand out in the bar of the Queen Elizabeth Hall at a storytelling festival that included Hugh, Duncan, Ben Haggarty and Louise Bennet. The thought makes me cringe now, but it is not something I regret. Self-belief, even if it is at times delusional, is a powerful engine and helps keep up the momentum as we journey on even further on our chosen path.

It helped that I was broke, having lost my position as bookshop manager at Colchester Arts Centre when the Eastern Arts Association decided to stop subsidising the shop. I had been given the post as a way for the then Literature Officer of the Association, Laurence Staig, to keep me alive as a poet. During my time there I had seen the Company of Storytellers, who rekindled an interest in storytelling in me. Before seeing them, it had never occurred to me that this was a way to make a living, but their inspiration was an important step in my journey. The final push came from the wonderful Tarby Davenport, the unsung heroine of the East Anglian arts scene who has probably done more than anyone I know to bring quality unusual performance into the public arena. Calling in at her cottage on the way back from a poetry reading, she mentioned it was a pity I wasn’t a storyteller because she could give me some work. ‘By an amazing coincidence, I am!’ I replied and so began my voyage into unchartered waters.

In retrospect I had been unconsciously preparing for this my whole life. I grew up without television and listening to Children’s Hour every evening on the wireless there was always a story. Before I went to bed my mother would always read me a folk tale or a poem from our set of Arthur Mee’s Encyclopaedias. I still remember the excitement of visiting The Ideal Home Exhibition at Earls Court where the salesman convinced my parents to buy this treasure trove of fact and fiction. This was how we spent our evenings as we waited for my dad to come home on leave from whichever ship or air station he was serving on at the time. Once home I would listen wide-eyed to stories of his travels, poring through old photo albums of his pre-war navy life; I was fascinated by his accounts of crossing the line (the equator) and King Neptune. He talked for hours of his early days at sea and of the hardships and adventures of his youth on Vancouver Island (a journey he made alone by boat and train from Sudbury in Suffolk at the age of fifteen).

These were my foundations which I continued to accidentally build on later in life when, after many of my own adventures, I decided to write about a time traveller. Dressing as a medieval pedlar I walked around Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk, living as Samuel Partridge, pedlar of Beccles. To add substance to my character I learned a few East Anglian tales, telling them along the way. I never did write the book, but the experience was invaluable when, eight years later, I decided to ply my trade as a storyteller.

I was lucky in at least one respect in that I did not have a problem standing up and performing in front of people. I had spent over twenty years as a performance poet taking poetry into areas not used to hearing it. Touring with Nick Toczek in Stereo Graffiti we took over hotel dining rooms in Edinburgh during the Fringe, where we picked up a local audience, and were studiously ignored by the regulars in Yorkshire working men’s clubs. In Ipswich Arts Theatre where my wife, Rose, worked as theatre electrician we put on free Monday night shows, combining poetry with the theatre of the absurd. There, Pam Ferris taught me that the stage was not a great desert but a space that could be covered in a few paces. All this was training for my future as a storyteller; a little random, maybe, but all useful.

Having got a head full of stories, or at least enough to cover an hour or so of performance, I soon realised that even if I could get the work I was nowhere near ready. I tried to sound like the storytellers I had heard, people who leant forward as if imparting great secrets to their audiences. Their stories gradually unfolded, sucking the listener in, creating spaces in the mind where anything could and generally did happen.

I tried, but I felt I was wearing handcuffs. I was from a world of rock ‘n’ roll, jazz and performance poetry, an Essex boy, born in Barking and growing up in Harlow New Town. I did not have, as was pointed out to me later in my career, a storyteller’s accent. Gradually it dawned on me that things might improve if I stopped pretending to be someone I wasn’t.

I recalled the words of the great jazz trumpeter, Miles Davis: ‘Sometimes it takes a long time to play like yourself.’

I remember storytelling to a group of foreign students at the University of East Anglia. At the end a Japanese man came up to me and asked in a mild-mannered voice, ‘Please, how do I become a storyteller?’ All I could say was the first thing he had to do was to forget everything he had seen me do. It was obvious that my somewhat flamboyant style would have been a disaster for him to try and emulate.

I have always dressed up to perform. I think it give me a freedom to be expansive. It is like dressing to go out for the evening or to go to a job interview. It was and still is my public self. One half of who I am. When I started telling, I took Samuel Partridge back out of the wardrobe and became my medieval self. But this was too time-specific for me, so I reverted to the top hat I had retrieved from a dustbin in Birmingham fifteen years earlier when I was with Stereo Graffiti. There was an old dame school being emptied next to our drummer’s house and I watched all kinds of treasures go into the bin, dance cards from 1920s cruises, tins of coronation chocolate, Aston Villa season tickets from the 1890s and an immaculate silk topper. This became the basis of a look that has stood me in good stead for a quarter of a century.

There are those that say a costume gets in the way of the story. This may be true for some people, but we dress for each occasion in the way that makes us most comfortable and relaxed, and storytelling is no different. Apart from that I tell a lot of open-air events, offering stories to individual families. If I was dressed in jeans and a T-shirt they might understandably call the nearest constable. The costume seems to legitimise me.

Storytelling in the open-air was something I drifted into, partly by choice, partly by necessity, but mainly through coincidence.

Margaret Thatcher’s attack on the public sector meant the arts would inevitably come in the firing line and soon for all but the best-known names, subsidies began to disappear. As well as losing my position at Colchester Arts Centre and the closure of the bookshop, the regional Writers in Schools scheme was decimated. No longer were local artists supported in any way financially, but even my income from touring schools as a visiting poet vanished.

There were many advantages to cutting my teeth on the do-it-yourself culture of Ipswich and London in the 1960s, the Albion Fairs in the 1970s and the punk explosion in the 1980s, one of which was to realise it is possible to create your own audiences and circuits without relying on any establishment to do it for you.

I went back to my own people, that mixture of beats, hippies, anarchists and greens, and individuals like Tarby, who had been immersed in the folk culture since the early 1960s and who started promoting because she couldn’t find anything she wanted to see in her own area.

She booked me for events around Suffolk put on by councils who had not yet felt the full effects of austerity. Strawberry Fair in Cambridge opened up the festival circuit for me through one of those coincidental conversations. I was taking a break between telling at the fair and chatting with Tony Cordy when I mentioned that it was disgusting that an old hippy like me had never been to Glastonbury. He was running Green Kidz that year and gave me two tickets and some diesel money to come and tell stories. That was in 1991 and I have been working for Tony – who has been running Glastonbury Festival’s Kidz Field for over twenty years – ever since.

But sitting and waiting for the phone to ring when few people know you exist does not bring home either the bacon or the tofu, so I devised a plan to get some regional publicity.

I went to Charlie Mannings, who had the fairground at Felixstowe. It was the beginning of the season and we both needed publicity. I asked if I could busk at the fairground in front of one of the rides for the season so we could get some coverage in the local and regional newspapers. The plan worked, and we got a good spread in both the Ipswich Evening Star and the East Anglian Daily Times, one of the biggest regional newspapers in the country.

I hardly made any money, but it taught me a lot about working an openair audience and for years afterwards I would meet children in schools all over the country who remembered seeing me at the fair.

For the next couple of years I would tell stories anywhere people would have me. Some festivals got me for the price of a ticket, but only once. The next year they paid. My reputation as an open-air teller grew and Cambridge City Council booked me for their ‘Summer in the City’ programme and from this came the Folk Festival where, with the support of the then director Eddie Barcan, I established the storytelling area.

Forever trying to get storytelling into areas where it was not established, I told in holiday destinations from Center Parcs (where Christine Willison, the editor of this collection, was already telling) to Lapland. I became the first Storyteller in Residence in a British prison, and got the first publicity for the now well-established Storybook Dads scheme, and have visited schools on four continents.

It has been wonderful and frustrating. There have been times when it was difficult to get work in schools because I was thought of as just an open-air performer and keeping an eye on the ever-changing goal posts in the arts world gets more difficult as the years progress, but I chose my own path, so I have no complaints.

I still swing between feeling like a charlatan and a complete novice as I watch a fantastic array of new tellers come on the scene cutting their own swathe.

Meanwhile I rejoice at the opportunities I have had and am still having as I sit on a mountain in Romania collecting yet more stories.

KEVIN CROSSLEY-HOLLAND

Most young children hear stories, and follow them on screens, well before they can fully understand them or read them for themselves.

John Stuart Mill was right when he wrote of childhood memory as ‘the present consciousness of a past sensation’; and applied to the first hearing of a story, that consciousness is primarily of the music of story – that’s to say the music of language – which is all the more significant in this modern generation besotted by the visual.

Think of the pulsing beat, repetition and rhyme within nursery rhymes that we carry with us all our lives, and love to introduce to our own children and grandchildren. ‘This little piggy went to market’ is unforgettable. ‘There was once a very small pig who went to the market’ is not.

I don’t have anything like total recall of my childhood – who does? – but when I was six or seven my mother taught me simple memory techniques. I used them then, and I still do. But earlier still...