4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Odyssey Books

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

Andal’s Garland

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 428

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

A rich and immersive sensory experience of Indian life, culture and history; a story of beauty and poetry of the 8th century interwoven with a contemporary search for self-enlightenment. The retelling of two women’s lives and their unrequited love for god or man. Meticulously researched. Evocative description and sense of place.

Cass Moriarty

Saisha, an Australian traveling in India with her partner, Marcus, makes a chance purchase of a book of Tamil poetry from a Delhi market. The yearning verses precipitate her quest to discover more about their author Andal, the revered young tale-teller of a thousand years ago, a girl with goddess eyes in thrall to the sapphire-skinned Lord Vishnu. Saisha, questioning the faltering bonds of her own relationship, returns alone to southern India to trace this intriguing story. Helen Burns carries readers safely aloft amid scents of sacred basil and rose and the push and shove of temple towns as Saisha is wooed by the mystique of the revered poetess and succumbs to the irresistible pull of Mother India, that most divine of temptresses.

Susan Kurosawa

I have no doubt that Helen Burns writes under the immense and long-reaching aegis of Andal herself. Saisha’s longings resonate with echoes from a distant time, in which a young poet learns to transcend the world through verses that reveal the secrets of the aching heart and the eager body. Gently philosophical and elegantly erotic, Andal’s Garland has a narrative charge that spans centuries and continents with ease. What a lovely book this is. I could say it over and over, like Andal’s own parrot might.

Sharanya Manivannan, author of The Queen of Jasmine Country

This is a book for pilgrims. Every so often in a life there's an urgent and mysterious summons, and – it can happen very abruptly – you find yourself on a pilgrimage. I read Andal's Garland at such a time in my own life. It's a wise, thoughtful, passionate and necessary companion.

Peter Bishop, Creative Director of Varuna – The Writers' House

Andal’s Garland

the fragrance of a young girl’s love endures a thousand years

Helen Burns

Copyright © Helen Burns 2021

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Published by Odyssey Books in 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian Copyright Act 1968), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of the publisher.

www.odysseybooks.com.au

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available

from the National Library of Australia

ISBN: 978-1-922311-36-8 (pbk)

ISBN: 9978-1-922311-37-5 (ebook)

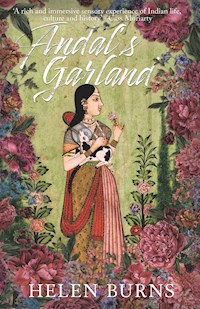

Cover design by Elijah Toten

Cover image ‘Girl holding a Calf’ via Rijksmuseum under a

Creative Commons licence (CC0 1.0 Universal)

Author’s Note

Andal’s Garland is a work of fiction, an intertwining of venerated themes, historical and mythic, with the experiences of a contemporary woman. Due to the intricate nature of culture and religion, I do not claim any ultimate authority and humbly apologise for any inadvertent error or misrepresentation. I remain ever thankful to the gracious people of South India.

Tirumal, in fire you are the heat

in flowers you are the scent

among stones you are the diamond

Kirantaiyar 500 BC

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Share your thoughts with us

Oh heart! Meditate on Andal

born in Villiputtur where swans wander.

She took the flowers adorning her body

and garlanded the Lord of Arangam.

She sang to Him her Tiruppavai,

precious garland of songs.

Uyyakkondar 10th Century

Prologue

On the first day in the month of early dew, Andal woke long before the sun. It was the hour of Brahma, when the gods were nearest, so close his breath might brush her cheek. Birds were still asleep in their nests, heads tucked into wings, eggs cosseted. Moon-flecked shadows of tree branches and tall houses laced the earthen streets outside her window. Andal lay for a moment in this quietest hour of all, sensing the imminence of something or someone quilting the air of her room, breathing into her, pounding her temples, beating at her ribs.

Stars still crowded the dark square of sky above the courtyard as she drew a pail from the well. The water was cold. She braced herself before splashing her face. She combed coconut oil through her raven curls and twirled them on top of her head, then tied a length of homespun cloth round her waist, pleating the end and tucking it in at the back. She laced her bodice and wrapped a shawl round her shoulders. She was twelve years old now, of a marriageable age, so she veiled her head before unlatching the gate of her father’s house.

The oil lamps had burned dry, leaving the streets in delicious darkness. Andal felt reprieved, for a little longer, before the buds of the moon lilies closed in her father’s garden, before the pleas of her mother, the neighbours’ gossip and, from the only one who mattered, his stubborn silence. Except for the occasional bell of a foraging water buffalo and the skip of her feet through the night jasmine air, nothing else was perceptible. In the company of so many stars Andal felt an uncomplicated joy, free from the familiar despair that pooled in her throat like a pinch of salt dropped into a tumbler of water. Like the circle of ripples only ever rumouring his reflection at the bottom of her well.

Skipping faster to leave the thought behind, she followed Villiputtur’s wide main street, past the entrances of its two-storey houses flanked by carvings of dragons rearing twice her height. Those giant elephant trunks hanging from their sculpted mouths—how she had shrieked with fear and delight hearing her father describe these guardians with their crocodile head and lion legs, their monkey eyes and peacock’s tail. She passed the scents of sacred basil and roses, pungent and sweet, infusing the air of her Appa’s temple garden and, on the other side of the wall, the gateway of a thousand gods leading to Lord Tirumal’s temple. Then, through a labyrinth of alleyways and thatched dwellings, she skipped to the edge of town.

Andal balanced across the bunds of two paddy fields. Here, she could see for miles in ten directions. She looked to the eastern horizon beyond which, people said, were the waves of a great sea. Hints of lilac turning to crimson washed the sky, dismantling all of its stars. But there was one bright light rising as if it, and not the sun, claimed that particular morning, Venus. Andal turned around to face the dark red-rimmed peaks of the Western Ghats. Hovering in the crevice of two mountains was another bright star, Jupiter. After watching its descent, Andal turned again to Venus but she too had disappeared.

Women were already gathered at the low stone temple on the banks of a sacred river. Its source was a spring bubbling up through the floor of a cave deep within the ylang ylang forests of the mountains. From Villiputtur it snaked a slow path across the plains to the sea. For the next thirty dawns in this early dew month of Margazhi, they would bathe in its chilly waters offering rituals to Katyayani, the goddess their ancestors had invoked since the beginning of time. But now their drumbeats and incantations summoned the presence of a god as well—a blue-skinned god who flew between worlds on the back of an eagle and made his bed on the coils of a snake.

It was he who swung the pendulum of stars that morning with four arms raised holding a discus, a lotus, his conch and mace. He watched Andal unable to contain her excitement, standing midpoint in this rare conjunction of Venus and Jupiter.

Chapter One

Where Coromandel flowers entwine celestial worlds

there the primeval one holds a fiery discus.

Bring me close to its glow—but do not scorch me

Nacciyar Tirumoli 10:3

For the Love of God. Icounted fifteen rupees into the book-wallah’s hand. A playful title, was my first thought. Of all the paperbacks I had picked up and put down on that marathon Sunday morning this was the one I chose. Marcus and I had walked from Jamma Masjid to Chandi Chowk. It was the last day of June, pre-monsoon and dripping hot. Any moment my legs would crumble and I’d expire into a puddle right there on the pavement. But I didn’t fall, because that was the moment I saw her. The book’s cover was creased and faded, its thin spine torn, and there she was dancing on the front. A copper engraving of a girl, hands raised above her head, feet poised.

I skimmed the back cover. The title had nothing at all to do with the cry of a woman at wit’s end, it was a book of Tamil poetry. Flipping through its yellowed pages, I stopped at the verses of a girl called Andal. She was the only female in the company of twelve poet saints, the Azhwars, who lived more than a thousand years ago.

Clouds, dark as clay moulds, I am the wax inside you. Rain down on Venkata where Tirumal lives, caress my body and soul, melt my heart, pour him into me.

I had no idea where Venkata was or who Tirumal might be and had never heard the name Andal, but there was a charge to the words, as if the entirety of love had been condensed into four lines. For the rest of the day, as we traipsed the streets of Old Delhi, all I felt was impatience to return to the quiet of our tiny hotel room. I am the wax inside you. I had dabbled with the I Ching and alignments of stars, but arriving at these words felt like an altogether different kind of divination.

I had lost count of the times we had come to India, Marcus and I. What mattered more were the twenty-five years stretching between us since meeting there. India was a land that bound us. Two days after our first encounter we were sharing a bed. The romance of those early years, roaming about in our cheese-cloth clothes and faded jeans, had all but disappeared and it seemed those wild-eyed days, when my young self recklessly poured into the body and mind of another, had never happened. And yet I continued to believe Marcus and I had staying power; we defied the odds and rode the changes. What was it keeping us together? For me it was more than an attachment to comforts and habits or the fear of living alone. More than companionship or convenience. The reason of us ran deeper. But love? I found myself asking more and more: was it love?

Thinking back to that night in the refuge of our hotel room, windows closed to Delhi’s Armageddon air and the air-conditioner turned high, I took a long breath and picked up my new book. It fell open at the same page—Caress my body and soul. I closed my eyes and tried to imagine.

Marcus slept as I read by torchlight. Verse after verse, late into the night, I devoured the words of a girl. Then I read the legend of her life in a small annotation at the end. It was like a fairy tale, her birth from the red soil of a temple garden, and how she vanished at the age of sixteen. My mind swung between the reality of the lines I had bookmarked and the girl who composed them. How much of the myth was true? And what to make of her poems?

Love tortures me, I burn in its flames. All night I lie awake, a target for the southern breeze.

Love tortures—the words careered inside me.

I didn’t know what dream it was to later jolt me awake, and what the lines I had scrawled in the dark meant: my heart an ocean of unuttered love, even in a sandstorm I sweep the threshold of my house.

I didn’t know then that this girl, this revered Indian goddess, was the guest I had been waiting for.

For the Love of God became as constant a companion as Marcus until one perfect summer morning at home I felt the familiar pull to return, and he did not.

‘We were only there four months ago. Look at the sky, Saisha, the sea,’ he said, with his surfboard under his arm. ‘No way am I leaving this for lungfuls of leaded air. I can’t afford to get sick again. It took weeks to recover from whatever strain of Asian flu I caught last time.’

I sat there, staring at the ray of sunlight hovering near my feet, uncommonly sullen. I felt her—Andal—the sweep of her goddess eyes vibrating the air between us.

‘Come,’ she called from her temple garden thousands of miles away.

Marcus didn’t hear the sound of her voice, but it was clear as a bellbird’s for me.

‘What about a summer in France? Ockitania. You’ve always said you wanted to return. Let’s plan for next year.’ He stood there, like a foreigner, and she called again.

‘It’s Occitania!’ I said, my gaze bypassing those penetrating eyes of his. The sea was not the only reason we had chosen this house, there was also Wollumbin, the view of its crooked peak through our kitchen window. On that day, like so many others, its tip was veiled in cloud and I remembered its second-hand name, Mt Warning.

‘Your grandmother,’ he said. I looked at him blankly, and at those clouds swirling behind him.

‘She’s given you the keys. Let’s go before the roof falls in.’ The roof was fine. But he was right, grand-mère had insisted her house wasn’t to leave the family. My mother had no intention of returning, so I was it.

‘The house is built of stone, Marcus. It’s not going anywhere and now isn’t the right time.’

Marcus surfed and Marcus returned, so sure of himself, sure that I would come to my senses. He stood there, wetsuit draped over his chest, diamonds of saltwater clinging to his skin. A long time ago I would have crossed the room for a taste of that ocean.

‘It’s Margazhi, the Tamil month of ancient bathing rituals. Just imagine,’ I pleaded, ‘golden chariot processions and all of Srivilliputtur’s women chanting Andal’s songs. Marcus! I really, really want to go.’

Life happened to me for the most part and I dealt with the consequences. Occasionally though, a set of circumstances might unfold answering a desire I harboured but lacked the courage to acknowledge, let alone speak. Close to midnight I pressed pay for my ticket. A thrill ran through my body, then a flood of relief.

Mid-December to mid-January is a winter month. Tamilians call it the month of early dew. I stepped from an air-conditioned terminal into an onslaught of touts, taxi drivers and money changers, each with probing dark eyes, and smiles gleaming beneath manicured moustaches. Winter? Sweat had already beaded my forehead. Smoke-hazed, crow-call filled air assaulted my ears and nose.

It was impossible to prepare for the days, sometimes weeks, it took to navigate the portal into India, an unpredictable overwhelm of wonder, confusion, irritation, light-headedness, before emerging through to the other side charmed and surrendered. Perhaps this was the reason I kept returning since my first visit all those years ago. I knew by now, no matter how many times I dreamed my arrivals from the comfort of an Australian veranda, there was no safe passage, no alternative to the unravelling of a time and logic I took for granted in the West. Simple or complicated, most questions in India are met with the universal swim of a head. Did it signify yes or no? I was never sure. Three requests for a street direction and I’d be given three different answers. Sometimes none of them true.

Ensconced in the brown velvet seat of an Ambassador taxi, happy with the negotiation of a fare to Srirangam and the good-luck twinkle in Ganesha’s gemstone eyes as he bobbed up and down on the dashboard, I let go into the life outside my window: wastelands of dust and auto shops, fruit stands and a shining new supermarket, an errant cow and a woman dressed in pink brocade gliding her hand over its back as their paths crossed. The driver sped us toward the Kavery River and the other side of town, a domain of tradition, of temple towers and Brahmin streets, pilgrims, and bicycle rickshaws.

Nearing the bridge, we slowed into the chaos of two lanes being widened into four. The driver made a comment in a tumbling of Tamil then pressed his horn as we crawled ahead, eventually coming to a scattering of onlookers lining the remains of a verge. A bulldozer was crushing the plastered walls and bamboo struts of an entire row of houses. The taxi driver released his hand. I watched the listless shape of an old woman on a bench marooned in a rubble of rocks, the palm fronds of a roof at her feet broken as a shipwrecked sail; one half of a house behind her. Unapologetically sliced in two. I shifted uncomfortably in my seat. Its three inside walls were painted blue, everything in order—a small kitchen, a chair, shelves neatly stacked with cooking utensils, and a calendar. I felt a prickling of goosebumps down my arms as if the tip of a knife was lifting my skin, testing its limits—one life severing into two.

Neat and ordered was how I had left our house. Everything in place, everything spotless—an attempt at wholeness, a way to make the leaving easier, to soften the unforgiving gaze of Marcus, as if a lint-free carpet meant anything to him. ‘Why can’t you be happy with what you’ve got? You think leaving is going to change things?’ Over and over like a broken record. All it did was make me more determined.

It was enough, at first, our renovated house and trellises of vegetables, Marcus’s carpentry and my part-time hours as a nurse’s aide in a retirement home—each room a capsule of memories real and imagined, beside every bed a tableau of wedding photos, sons and daughters, grandchildren and great grandchildren. It was as much my job to listen, as it was to take a pulse, to bathe and feed the residents in my care; each story recounted, a way of circumventing their years. Then I’d return home to us, our unconscious lapses into habits punctuated by shared moments. If I had attempted to change the rituals of our days, would these tinkerings have made a difference?

As the taxi picked up speed, I turned in my seat to look for the woman again, for a glimpse of her face, her expression—would it be resolve or resignation? Or no expression at all? I had seen lives reduced to that. The street and its demolished houses had disappeared into dust.

The island of Srirangam marks the end of Andal’s story. It was the temple city where she dreamed her wedding,and here I was freshly tumbled out of a plane, about to cross the Kavery River into its arms. Srivilliputtur, where Andal’s story began, was still another half day by train. I added up the hours it would take, then counted out the petals of a brown velvet flower in the taxi’s upholstery—he loves me, he loves me not—falling into the games my mind sometimes played in its attempt at icing everything into order when clearly the world rushing by outside my window was anything but. Another lone cow with a plastic bag hanging from its mouth ambled across four lanes of cars, motorbikes, and three wheelers. A bus careered into one-way traffic setting off a cacophony of horns. School children pedalled home oblivious to the cars swerving around them and December’s sun shimmered the dust.

One night, that was all Marcus and I had spent in Srivilliputtur on our last trip, me holding tightly to the tattered pages of a poetry book found in Delhi a month and a half before. What were the odds in a country of more than twenty-five million people and twenty languages, and a hundred thousand gods, of then finding myself in the town where the poems had been written, three and a half days’ train journey south? Was my path to the feet of a girl with a green parrot perched on her shoulder nothing more than serendipitous? It was as if I had been turned upside down, swung around in mid-air, then dropped into a myth that was not, in the eyes of Andal’s devotees at least, a myth at all. Every day in Srivilliputtur they sang her songs and called her their mother. Andal, the goddess who refused everything except love.

I threaded my bangles up and down each arm, feeling their reassuring coolness, as the taxi braked, accelerated, and horned us on.

‘A lady without bangles is undressed,’ the old woman behind the counter had admonished as she slipped my hands through circlets of green and red glass. I had bought them on that one night in Srivilliputtur’s temple arcade, then the next morning we were whisked off on an altogether different kind of pilgrimage. I kept those bangles like talismans. You will return, I had promised myself, watching the tall tower of Andal’s temple grow smaller and smaller, as we sped toward a mountain called Chathuragiri.

I didn’t know then that both these places were portents for me.

The towers of Srirangam’s temple city came into view above the lush greens of coconut and banyan trees. ‘Stop,’ I said to the driver. ‘Is there a ferry?’ He turned to me with a look of alarm. ‘But, madam, in two minutes I am delivering you.’ He pointed to the wide river we were about to cross. ‘It is dangerous for a foreign lady and the ferry stop is two miles upriver.’

‘I will pay you.’

The Kavery is a river as sacred to the Tamils as the Ganges is to all of India. Once there was no bridge and all pilgrims, rich and poor, were ferried by boat. This was the very river Andal crossed on her way to the dark-skinned god she called Lord Ranganatha—her last recorded journey. I stepped into the small wooden boat and the ferry-wallah pushed us off. He was an old man, sinewy and weathered. I leaned into the rhythm of his oars as the river carried us, wondering if it might be ignorance, reducing life into a beginning, middle, and end, when these dynamics are happening in every moment. Downstream on Srirangam’s banks, wood-smoke curled lazily into the haze. Silhouettes of pilgrims were turned toward the sun, three times submerging themselves for purification. Wherever a pilgrim steps into its water—at its source in the mountain ghats, where their god reclines in the temple’s sanctum sanctorum, or where the Kavery is finally swallowed by the Indian Ocean—it is the same river, indiscriminately generous with its blessings.

We dipped and glided toward Srirangam’s banks. It felt as if this passage across the river was somehow more of a separation from Marcus than the twelve hours of flight between Coolangatta and Tiruchirapalli. With each stroke of oar, I felt the division between us grow. What do you say to the man you fell in love with twenty-five years ago? What do you say to him when skeins of memories, of your love and despair, begin their unravelling? I trailed my fingers through the fast-flowing water, skimming small whirlpools of ash and marigold petals, of departed ones and pilgrims, and the intangibility of billowy clouds reflected all around us, banks of them building, shifting, and with each plunged oar, disappearing into ripples of molten silver.

What of this Tamil god Ranganatha known by a multitude of other names? He who has, as capriciously as this river, chosen to charge into my life along with all his incarnations—a boar, a tortoise, a baby floating on a banyan leaf, a dwarf, a lion, a blue-skinned flute-playing mischievous boy—none of it was logical. But that wasn’t the point. They were all doors into the same house, elements of the same river flowing toward an infinite ocean of milk where a lord known universally throughout India as Vishnu floated on the sinuous body of a snake. On other occasions he might choose to stand with his feet on the earth, his head in a heaven called Vaikuntha and his body absolutely everywhere.

Tirumal, Narayana, Vatapatra sayee, Ranganatha … no Hindu I had met appeared to have a problem with their plethora of gods and it didn’t seem to matter if a story mutated in the telling. The more the merrier. ‘But Tirumal,’ a priest said to me on that first night in Srivilliputtur, ‘is the name you can be giving all of them.’

I felt as if I had been coming to this ancient land forever, possibly even lifetimes. India was where I had first conceived. How close I had come, then, to my only child.

I was a wise twenty-one, unhinged from the trappings of the West. Returning home from my first adventure into the land of gods and goddesses and one lover whose face I cannot now recall, I clutched at the pain in my belly with a naive sort of disbelief. Blood started pouring from me for the first time in three months. Then I felt the slide of something whole as my body shivered waves of hot and cold. But in a few hours, I was diving into the sea telling myself all was well, it was meant to be. There would be other times. My life stretched from the small curve of my belly to the wide arc of the ocean’s horizon. The thought anything different might await never occurred. It was a year before my falling into bed with Marcus and almost four before I stepped, dazed, from a consulting room, taunted by the red desert silt of a painting hanging on its wall.

I caught glimpses of my thinning face between the ripples of each oar stroke and, to the bemusement of the ferry-wallah, cupped my hands, filling them with water again and again until my face and hair were drenched and I was laughing out loud. I didn’t mind what I saw, as I fell back into my reflection, the strands of soaked silver, the hint of a wilderness returning to those eyes. And then she asked me a question and I felt it like an uncoiling inside me. Who are you?

A long time ago I was content for hours combing a beach for perfect discs of stone. I’d skip them across the water, the more skips the better. Is that what I have been doing, only ever skipping the surface?

Chapter Two

I cooked sweet pudding for you

young paddy, pounded rice, sugarcane and jaggery

Nacciyar Tirumoli 1:7

Srivilliputtur was a town Marcus and I had never heard of before visiting our good friend the professor in Chennai. He had put a plan in place for us to meet him there, along with his entourage of pilgrims. Srivilliputtur was the closest train station to a village called Watrap in the foothills of the Western Ghats, and from there our ascent would begin.

‘Gods willing, I want to make one last pilgrimage to Chathuragiri mountain,’ the professor had said, cracking his knuckles and inching a stretch back into the cushions of his chair. ‘You please come with us. In one month we go.’

Marcus’s intrigue with everything alchemical and esoteric had led us to the professor’s door. Whenever we were in Chennai, we visited him. Despite the aches and pains of old age and an ailing heart, his mind sparked at the mention of a Vedic text, the Puranas, the Upanishads, the Ramayana. And if Marcus asked about any ancient yogic teachings, the professor effervesced with stories, caves and shrines to visit, and siddhars, whether living or dead, we simply must seek out.

I had ownedmy book of Tamil poetry less than two weeks and my mind could not settle anywhere in the conversation he and Marcus were having. Ascetic practices of holy men paled against the aesthetics of one girl poet and the verses I had been reading ever since that day in Delhi.

If we come with flowers for you, if we chant with devotion and meditate, our self-delusion, past, present, and future, will burn like cotton in fire.

Hoping for a pause in the conversation, I took the book from my bag and placed it on the table between us. The professor stopped mid-sentence.

‘Ah, the Azhwars. Have you been hearing their songs?’

I shook my head. The professor swivelled in his chair and pulled a leather-bound tome from a shelf. ‘Four thousand verses,’ he said. A whiff of moth, dust and the scent of yellowing paper filled the air as he opened it.

‘Iti iti,’ he read, stretching his arms out as if to hold the whole room. ‘Meaning is: this too, that too.’

‘Neti neti,’ he chuckled, returning to the page. ‘Not this, not that. Which one do you choose?’

He looked at Marcus. Long before I had discovered the downward dogs and shoulder stands of yoga, Marcus was walking his Marcus path, effortlessly folding his legs into lotus, eyes closed to the materiality of the world. His answer to the professor’s question was obvious. Neti neti.

The professor looked at me and I squirmed. I had no idea what my path was, or even if I had one. I had dabbled that was all. Meditating here, chanting there. I was curious but never curious enough, or desperate enough, to leave my life behind and forge into the unknown with anything that might resemble a singular purpose. Did the professor really expect an answer from me? Iti Iti. Neti neti. I traced my fingers over the girl dancing on For the Love of God’s cover.

India had been in my blood from the beginning but in a dreamy kind of way. As a child I spent hours poring over a photograph album belonging to my grandmother. She had wrapped it in a piece of velvet studded with mirrors and slipped it into my mother’s suitcase the day my father took leave from the navy to bring the two of us to Australia.

For Saisha, she had written in elegant loops and swirls of ink above the first photo, so my granddaughter never forgets her home is also here.

There she stood, a studio portrait, pressing her lips to my newborn forehead, one sepia mountain behind her. On the next page, my grandmother is kneeling, her head in the lap of a woman with kajal eyes, a diamante scarf covering her head.

‘Who is this?’ I asked my mother.

‘That is another French lady who was living in India. Your grandmother took a steamboat all the way there to visit her. She was called The Mother.’

‘And what does this say?’ I pointed to more of my grandmother’s handwriting on the opposite page.

‘When you are older, I will tell you.’

I did not forget. ‘Read to me, Mama,’ I demanded when I was taller.

‘It is something The Mother said to your grandmama. She has written it in Occitanian.’

My mother paused, as if remembering again the language of the life she had left behind, then slowly translated. ‘Running away from difficulties is never a way of overcoming them. If you flee from them you won’t be able to defeat them, and they have every chance of defeating you. That is why we are here in Pondicherry and not on some Himalayan peak. Although I admit being on a Himalayan peak would be delightful—but perhaps not so effective.’

‘Where is cherry?’

I remember my mother’s laughter. ‘Pondicherry, sweet pea. A town by the ocean in South India, a very long way from Grandmama’s house in the South of France.’ I turned the album’s page, to the stone cottage where I was born and behind it the mountain my mother often spoke about. On the opposite page, separated by a thin sheet of tissue paper, were sari-clad women, buffalo carts, and coconut palms. Two veiled lands shifting one to the other.

I felt Marcus nudge me under the table. Was the professor still waiting for an answer? His chin rested on his clasped hands, his eyes bouncing between the two of us.

Iti Iti. Neti neti. I wanted both, the pleasures of taste, touch, smell—but I wanted to be free from them too.

Drawing fingers through his white beard, the professor returned to the words in front of him. Flicking through page upon page of its swirling Tamil he said, ‘This is the Vaishnavite book of books, their magnum opus, the Nalayira Divya Prabandham. All twelve Azhwars are here. Nammalvar, Tirumangai, Andal—or Kodai, as she was called by her father when he found her—he was an Azhwar too. His name was Visnucitta.’

The professor stopped and tapped a verse, considering its translation. ‘I am like the flower emptied by the divine bee. It is one of Nammalvar’s songs. Some say he used to visit with Andal’s father.’ He sent a casual glance my way.

‘Now,’ he said, slapping the book shut, ‘to our pilgrimage. All the necessary arrangements have been made.’ He took a folder from a pile of papers and handed us an itinerary.

‘We will make ourselves comfortable in three-tiered wooden sleeper class for the overnight train journey south,’ he said. ‘Breakfast parcels will be there when we arrive in Srivilliputtur. A minibus will take us to the foot of Chathuragiri and then we begin the eight-hour trek to its peak. You youngsters can walk it! I will have to be carried.’ He gave a laugh as carefree as a child’s.

I looked at Marcus and could tell he too was daunted by the sound of a twenty-four-hour marathon.

‘Is it possible we can meet you in Srivilli …?’ I chanced.

‘Srivilliputtur!’ The professor chuckled at my attempt. ‘As you wish,’ he said, ‘but what will you be doing between now and then?’

He unfolded a map and proceeded to draw a plan of sacred sites and temples criss-crossing Tamil Nadu, and I wondered if one overnight train ride from Chennai to Srivilliputtur might not be an easier option. His pen moved south.

‘After three weeks you will arrive here,’ he said, circling the city of Madurai. We had visited its Meenakshi temple before and were happy to return—its labyrinth of halls and smoky shrines, its enormous resident elephant. ‘And then you go to Palani,’ the professor continued, marking the map with an asterisk. ‘From there you take a bus and get off here.’ He marked another asterisk. Ask for the siddhar called Mootai Swami, then you wait for a minibus to take you to a crossroads. From there it is walking distance only.’

We’ll see, I thought, conjuring up a few rest houses away from the mayhem, a balcony and a sling-back chair, birdsong and the sound of wind in the trees. One book in my lap.

The professor returned my Azhwar paperback and walked us to the street. He hailed an auto and negotiated a fare with the driver. ‘All of them rogues.’ He shook his head. ‘Even in heaven you will find them.’

As we waved goodbye, he said, as if an afterthought, ‘Oh, and if you reach Srivilliputtur before us make sure you visit its temple. Very beautiful.’

Marcus left me at a tea stall in Meenakshi temple’s marketplace, fortification for working my way through bolts of cottons before finding a tailor offering honest prices. After three weeks of travelling on passenger trains and antique buses, sleeping on ashram floors and scrambling over boulders in search of rumoured siddhars and their caves, I needed a fresh set of clothes. Marcus disappeared into the shadows of Meenakshi’s thousand columned pavilion.

When we met later, there was a spring to his step, and over lunch at our favourite hotel, as we crumbled papadams over rice and made our way through the twelve little bowls on our thali trays, he said, ‘I have found a place. I’ll take you there tonight.’

‘What, where?’ Knowing, as I asked, not to expect an answer. Marcus, a man of few words, aloof to the chatterings of the world—still a mystery after all our years together. Maybe that was it. Without the mystery the magic would go. Or the challenge. What were the words my grandmother had written, running away from difficulties …? I swallowed them with a mouthful of vegetable sambar. Love, I thought, how do you make sense of something that is not black and white? The dhal was salty and sour with tamarind, the rasaam, spicy. Fresh corn and beans simmered in a coconut gravy.

As we ambled through the maze of motorbike-choked streets, I glanced up to see a crescent moon hovering behind the southern temple tower. It looked as if it had been caught in the arms of one of the tower’s thousand sculpted gods, Hanuman, half-man, half-monkey. Police-frisked and bags checked, we strode over a high stone step into the domain of goddess Meenakshi. Marcus led the way through throngs of evening devotees to the steps of the temple’s teerthum where the moon was again, this time a reflection in the centre of its sacred water, released from Hanuman’s arms. Fountains sprang from the concrete lotus flowers at the teerthum’s edge, rippling the moon into slivers of bright light. Past the main shrine with a notice saying Non-Hindus-Not-Allowed, past Ganesha, his golden body freshly decorated with marigold and jasmine, and into a dimly lit corridor blessedly empty but for a few of the devout briskly walking, prayer beads slipping through their fingers.

Marcus brushed the back of my hand, guiding me toward a dark alcove where four men and two women sat silently meditating before a small black granite Shiva lingam.

Lingams were everywhere—revered in temple shrines or the roots of a banyan tree on a street corner, worshipped beside holy rivers and in secret caves—these smooth oval rocks an ancient phallic symbol appearing miraculously out of the earth. I had found the whole concept bemusing at first, sacred stones so overtly sexual, openly worshipped by men, women, and children.

Marcus had a library of books at home about this elementary force—Shiva’s subtle body in perfect union with Shakti—underlying every pulse of life. Books about kundalini and the serpent sleeping at the base of a human spine; what happens when it wakes and begins uncoiling through each of the seven chakras. Books about Tantra and the path to enlightenment; how to move from a world anchored in base desires to a finer, more pure awareness. Stories of yogis and yoginis living free from sexual entanglement and earthly attachments. I would run my fingers over the books’ spines, curious on one hand, but reluctant to open their dense texts. How overwhelmingly far I was from understanding Marcus’s resolve.

Evening eased into night. Except for the few ghee lamps lit by meditators, the temple alcove where we sat was dark. The man to my left was in full lotus, his eyelids open but both pupils disappeared toward his third eye. It was a rare sight in a temple, these singular bodies engaged in the channelling of breath and recitations of silent mantras, no hands out asking for favours, no grasping and pushing. To my right sat Marcus, serene and still, at home at last, the world left behind. Given the chance, I thought with a half-smile, he’d stay there forever.

In temples our paths often separated, Marcus staying put in an alcove or shrine and me off searching its rooms for places where women gathered, smearing kumkuman powder on the pregnant belly of a statue, offering flowers at the stone feet of a boy god playfully playing his flute. So, it was on this night, a few days short of arriving in Srivilliputtur, I shook the pins and needles from my legs and walked toward the clouds of camphor and incense smoke filling Meenakshi temple’s great hall. A sea of pilgrims were prostrating at the sanctum sanctorum’s entrance. It was a sight as ancient as the temple itself and I stood mesmerised in the midst of their faith, the stones thrumming at my feet like some primaeval consciousness fighting its way into my body. Two decades. Was it really that long ago? I found myself questioning the renunciation of my sexuality, my body. What time had numbed rose up raw again.

If I was ever caught in the net of wanting more than Marcus was prepared to give, I attempted to think my way out of it. He was caught too, I rationalised, between one world and another, the wild lone eyes of Saivite ascetics who disappeared for years into remote caves only to appear in the world again needing nothing and no one. And yet Marcus lived the life of a householder with me.

‘Choosing celibacy as a path liberates mind and body,’ Marcus had said.

After meeting in India, we returned to Australia and began saving for our dream of an idyllic life in the country. Less than six years had gone by—it still felt like honeymoon days to me, wrapped in the mystery of him, beguiling as those clouds swirling Mt Warning’s peak. I was only twenty-seven. I sat there, looking at him.

‘Celibacy?’

‘You will have more life force inside you, more energy for meditation,’ he said, before folding his legs into a half lotus and closing his eyes.

‘But how can you love me and yet never make love with me?’

If my question was tinged with emotion he did not reply. He doesn’t do emotion. I grew used to the strings of that net, despair and desire. Sometimes whole weeks slipped by without a tangle. There was flour to grind, bread to bake, a garden to weed, my three days of work in town. But I had no map, no way of understanding the serpent beneath the surface, coiled at my sacrum like the picture on the cover of one of his books. Mine slept on like the weight of a stone. Occasionally it might wake—if the whim took Marcus. I glowed for days, taking pleasure in the roundness and softness of my hips and breasts, the musk smell of Marcus’s skin on mine, and I hankered for more. But more became less and less. Weeks turning into months, months into years.

There were nights I lay awake, my body burning to dissolve into his, the idea of a higher path to god distant as the Milky Way swirling outside our window—there for the sole purpose of mocking my attempts at his idea of love.

‘I can’t do this,’ I moaned into the dark, squeezing a pillow between my legs or curling into foetus position and rocking myself to sleep. I was desperate in those early days; I clung to him, pleaded for a response, knowing all the while how pathetic it must look. And if Marcus did caress me, it was never enough; it only made me crave more. My body learned ways of survival. It knew touch meant eventual pain so it retracted from his touch, and that was a relief for Marcus.

Celibacy was his decision, not mine, and yet I chose to stay.

Away from the prostrating pilgrims, a young bride in cerise silk, arm in arm with her mother and grandmother, circled the image of a woman sculpted on a column, her ancient arms wrapped around her belly, her naked body glistening with sesame oil. The bride placed a red hibiscus at her feet, then offered a leaf-bowl of sweet rice.

There was no solace for me in the asceticism of sadhus, sitting on their cushions of stone, eyes turned inward away from the life pulsing all around them.

There was too much beauty in the world. Too much to love.

Chapter Three

Mysterious Tirumal

crowned with sacred basil,

honey-sweet, mischief maker.

How did you find me?

Nacciyar Tirumoli 3:2

We placed our trust in the auto driver, who drove us from Srivilliputtur’s train station to the fluoro-blue steps of a hotel on the edge of town. Our room’s air-conditioner worked, which was a plus, even though it sounded like a lawnmower. I unlaced my rucksack and took out For the Love of God. In the weeks since first setting eyes upon her, amongst the stacks of textbooks and trashy novels on the footpaths of Old Delhi, this copper-skinned girl dancing on the cover had taken up residence. She was the first to be unpacked and last to be packed. The book felt as permanent a travelling companion as did Marcus. It was an unsettling and inexplicable thought and I brushed it aside. The room was too tiny.

‘A bed and a bathroom of any description,’ Marcus rationalised with that endearing smile of his, never seeming to break free from its boundaries, ‘is a luxury you and I deserve, Saisha, on the eve of our climb up Chathuragiri. And the advantage of the air-conditioner,’ he went on, ‘is it drowns the thump of music and shouts of men in the sleazy-lit bar on the floor below.’

I threw him one of my smiles across the few square metres of room before opening to a random page.

There is a saying that no matter how much a person searches for a teacher, a guide or a guru, in the end it is the teacher who finds the one who is seeking. I thought about this as I looked at Marcus. What destiny catapulted us into each other’s arms all those years ago? We’d hardly exchanged names, and then we were living together. Sharing life with him was a kind of refuge, despite the challenges. He was my constant and he was kind, in his own quiet way. His mysteriousness drew me in like a magnet, but when he closed his eyes and lotus-crossed his legs, his presence felt more like an absence.

I returned to the opened page on my lap, scanning it for a verse to jump out. Who was this girl who composed these songs? And what was it about her longing and her despair that touched me so deeply? Was it as plain as that eternal conundrum, unrequited love, hers for a god and mine for this man I shared a bed with, but not my body? And why now, just as I am trying to read, does Marcus decide to banter away so uncharacteristically?

His sacred basil garland is all my heart desires. My mind grows wild.

Marcus and I did what we always do in the evening and set off for the local temple. But there were two temples, the hotel manager pointed out. The one he recommended was a temple to Shiva. ‘Inside you will be seeing the famous Nataraja, the cosmic dancing god.’ He stopped to light more incense for the small shrine on a shelf above his cash register.

‘Which way is it?’ Marcus asked. He had already decided.

‘Is that the temple tower we could see from our train?’ I interrupted.

As we curved one last time before the final stretch into Srivilliputtur, I had seen it rising above the town’s trees and tiled roofs, like a rainbow-coloured beacon.

‘No, madam, it is a different one. Twelve tiers this gopuram is having, the highest temple gateway in Tamil Nadu. Walkable distance, go left then left again near the bus stop.’

‘I’m going there,’ I said with a determination that surprised both of us.

Marcus turned right.

A coconut-wallah had set up his cart near a colonnade of trinket shops leading to the temple. I was thirsty. With a smile and a deft machete-whack, the wallah made a straw-sized opening. As I took long sips of its sweet, quenching water, a woman sidled up to me with garlands of green threaded on her arm. The scent of the leaves was pungent and spicy.

‘For god,’ the woman said, holding a garland to my face before the coconut-wallah had a chance to shoo her away.

He cut my coconut in half and carved out a primitive spoon from its husk to scoop out the slippery, transparent flesh. I turned to catch the garland seller, wishing I had followed my impulse to buy one for whoever the god inside was that I was about to meet. But there was another woman swaggering in her place with matted hair falling in thick dusty wads past her waist, her body swathed in faded red cloth hitched up to her knees. I caught a flash of the bangles covering her forearms and felt a kind of foreboding. She seemed out of context, too wild and unfettered for the quiet streets I had walked. Then she was gone—the scent of her heavy on the air for a moment, of sweat and smoke, earth and patchouli.

The temple was unlike the traditional square layout of others we had visited. Its walls were painted with the same red and white stripes, but it seemed more an L-shaped fusion of two temples, not one. I could see the top of its tall tower rising from another side and wondered which entrance to take. There was a sudden rush-rush of wings above me, a flock of white herons taking off from the sprawling branches overhanging the wall beside the coconut-wallah’s cart. Velvet-black wings swirled across the pastel sky and descended, taking the herons’ place. I traced my fingers across the wall’s stones, still warm from the day’s heat. A hush returned, once the fruit bats settled into their upside down roosts. A hush, unlike anything I had sensed in a long, long time.

I followed the length of the wall and came to another entrance. The gate was open. Inside, around an ancient low-ceilinged pavilion, was a garden hedged with jasmine, an oasis of perfumed shade, pomegranate and neem trees, hibiscus and roses. Before entering the pavilion, I glanced up into the quiet of the trees either side and noticed the silhouette of a small temple sculpted onto the pavilion’s roof. Carved into its niche was a painted garden and the figure of a Brahmin priest, his arms outstretched to the baby girl lying in the earth at his feet.