16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Serie: Bloomberg (UK)

- Sprache: Englisch

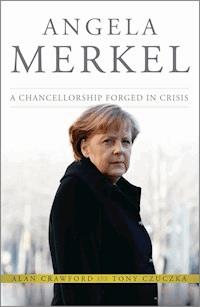

Shortlisted for International Affairs Book of the Year in the Paddy Power Political Book Awards 2014

Angela Merkel was already unique when she became German chancellor: the first female leader of Europe’s biggest economy, the first from former communist East Germany and the first born after World War II. Since 2010, the debt crisis that spread from Greece to the euro region and the world economy has propelled her to center-stage, making Merkel the dominant politician in the struggle to preserve Europe’s economic model and its single currency. Yet the Protestant pastor’s daughter is often viewed as enigmatic and hard-to-predict, a misreading that took hold as she resisted global pressure for grand gestures to counter the crisis. Having turned the fall of the Berlin Wall to her advantage, Merkel is trying to get history on her side again after reaching the fundamental decision to save the euro, the crowning achievement of post-war European unity. Merkel has brought Europe to a crossroads. Germany’s economic might gives her unprecedented power to set the direction for the European Union’s 500 million people. What’s at stake is whether she will persuade them to follow the German lead.

Angela Merkel: A Chancellorship Forged in Crisis is the definitive new biography of the world’s most powerful woman. Delving into Merkel’s past, the authors explain the motives behind her drive to remake Europe for the age of globalization, her economic role models and the experiences under communism that color her decisions. For the first time in English, Merkel is fully placed in her European context. Through exclusive interviews with leading policy makers and Merkel confidants, the book reveals the behind-the-scenes drama of the crisis that came to dominate her chancellorship, her prickly relationship with the U.S. and admiration for Eastern Europe. Written by two long-standing Merkel watchers, the book documents how her decisions and vision – both works in progress – are shaping a pivotal moment in European history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 378

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Contents

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1: Exodus (Merkel’s Journey)

Chapter 2: Revelation (Five Minutes to Midnight)

Chapter 3: Genesis (Eastern Roots)

Chapter 4: Numbers (Germany’s Subprime Scandal)

Chapter 5: Job (Greece as Euro’s Nemesis)

Chapter 6: Lamentations (Safe European Home?)

Chapter 7: Joshua (Merkel and the U.S.)

Chapter 8: Judges (German Model)

Chapter 9: Kings (Merkel’s Contemporaries)

Chapter 10: Apostles (How She Works)

Chapter 11: Proverbs (Where To?)

Chapter 12: Chronicles

Appendix – Photo credits

Bibliography

Index

Since 1996, Bloomberg Press has published books for financial professionals as well as books of general interest in investing, economics, current affairs, and policy affecting investors and business people. Titles are written by well-known practitioners, BLOOMBERG NEWS® reporters and columnists, and other leading authorities and journalists. Bloomberg Press books have been translated into more than 20 languages.

For a list of available titles, please visit our website at www.wiley.com/go/bloombergpress.

This edition first published 2013

© 2013 Alan Crawford and Tony Czuczka

Registered office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with the respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Crawford, Alan.

Angela Merkel: a chancellorship forged in crisis / Alan Crawford and Tony Czuczka.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-118-64110-1 (cloth)

1. Financial crises—Germany—History—21st century. 2. Germany—Economic policy—1990- 3. Merkel, Angela, 1954- 4. Heads of state—Germany. I. Czuczka, Tony, 1959- II. Title.

HB3789.C73 2013

943.088′3092—dc23

[B] 2013011633

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-118-64110-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-118-64107-1 (ebk)

ISBN 978-1-118-64109-5 (ebk) ISBN 978-1-118-64108-8 (ebk)

Acknowledgements

The idea for this book was hatched during a European Union summit in Brussels, but it was in a bar adjacent to the former U.S. Embassy building in Berlin that the opportunity to write it first became reality. After nearly three years of turmoil, the story of Angela Merkel and Europe’s debt crisis had reached critical mass. As our colleague John Fraher, one of Bloomberg’s managing editors, put it: The planets had aligned and now was the time to grasp our chance. Within two days we were at our writing desks, suddenly realizing the magnitude of the project.

We set about it armed with our own reporting from across Europe before and during the crisis; we re-examined speeches, trawled through public comments, mined archives and interviewed key participants in Berlin, Paris, Athens, Washington and elsewhere. The nature of any book examining the most powerful political figure in Europe, a serving leader, means that many of those who know the most are reluctant to speak openly. As a result, this work is based partly on discussions with European and U.S. officials who declined to be named, yet were important to portraying their side’s version of events. Though we agreed not to identify them by name, we wish to thank them for their contribution.

First and foremost, we would like to thank Bloomberg’s editor in chief, Matt Winkler, who approved our project and whose interest in the German chancellor was indispensable to making it happen. This book is a collaborative effort, which means it’s also a tribute to the depth of knowledge and reporting by Bloomberg journalists worldwide. We had access to the expertise and articles of colleagues in the government and economy teams, but also in bonds, finance and currencies, in Europe and in the U.S., in print, television and the pictures department. Our thanks goes to them all. Notably, we wish to thank the government team in Berlin – Leon Mangasarian, Brian Parkin, Rainer Buergin and Patrick Donahue – who covered for our three-month absence without complaint during a time of crisis, literally. Leon and Stefan Nicola conducted interviews of two German officials that we gratefully included. Special thanks go to Maria Petrakis, Simon Kennedy, Jana Randow and Helene Fouquet for their help in providing contacts. We would never have gotten to that stage had it not been for the backing of Reto Gregori, Bloomberg’s chief of staff, who provided the initial encouragement. John Fraher and Dan Moss fixed it for us to embark on the project, providing us with the time and travel needed. Our thanks also to Jim Hertling, whose spirited leadership of European government news and enthusiasm for the German story kept pushing Bloomberg to stay ahead of the pack.

Having the Bloomberg name behind the project opened doors. Many of those we spoke to did so because they trusted Bloomberg to paint an accurate picture of what happened during the crisis that almost brought the euro area to its knees. We hope that we measure up to those standards. We would like to single out Xavier Musca and Angel Gurria in Paris, who gave us the confidence at the outset that we were on the right track, and George Papaconstantinou, who graciously invited us into his home in Athens. Holger Schmieding and Carsten Brzeski gave us valuable feedback on substance and style. Our Bloomberg Muse team colleague Catherine Hickley offered key advice that greatly helped us to fashion the end product. Finally, we wish to thank our families – Judith, Freya and Magnus; Barbara and Adrian – for their resilience in the face of often absent and regularly moody husbands and fathers all through the tumultuous times of crisis culminating in the writing of this book. Judith Crawford, a political scientist and artist who grew up in East Germany, taught her husband about the true resonance of Europe. Barbara Kramžar, Tony’s wife and inspiration, spurred him with her energy, understanding of the euro’s significance and feel for the nexus between politics and human nature. We dedicate this book to them.

Chapter 1

Exodus (Merkel’s Journey)

As a young woman, Angela Kasner would set out from East Berlin each summer on a pilgrimage to the furthermost reaches of where it was permitted to go. While others left to tend the fruit trees and berry bushes of their countryside dachas, Angela traveled south through Dresden, where the wartime remains of the Baroque Frauenkirche were visible from the railway station, on to the faded capital of the Czechoslovak Republic, where the Prague Spring had long since reverted to winter. From there, she went to Bratislava on the Danube river, which formed the border with Austria and the unattainable West, then on to Budapest, where she occasionally mingled with the few Western visitors who visited; some told her the city’s parliament building and river setting reminded them of far-off London.

From Hungary it was across Romania on the long stretch east and then south to Bucharest, where Nicolae Ceauşescu was pursuing a policy of openness toward the West, a course that he would later reverse with brutal effect. She recrossed the Danube at Ruse on the Bulgarian border before arriving at Pirin in Bulgaria’s southwestern corner, the end of the road. This was as far as she was able to travel. There, in a mountainous region known for its brown bears and wolves, the pastor’s daughter who would become German chancellor looked longingly from the heights across the border toward Greece just a few kilometers distant. Greece, she thought; I’d like to go there, if even just once in my life.1

• • •

Angela Merkel’s political journey took her to become Germany’s first woman chancellor and its first from the former communist East. As she was sworn in on November 22, 2005, she could not have imagined the role that Greece would play during her time in office, nor the significance that her eventual trip to Athens in the fall of 2012 would assume.

Greece and its aftermath were to mark the evolution of her chancellorship, forcing her transition from one of many political leaders in Europe to the region’s pre-eminent crisis handler. Faced with economic and financial turmoil stemming from Greece that threatened the euro, the singular achievement of the unprecedented period of post-World War II peace and unity, Merkel was forced to evolve and adapt in ways that tested her ability to balance external demands for greater action with domestic political constraints on doing so. For Merkel, Greece was the pivotal challenge of a chancellorship forged in crisis.

Barring an 18-month honeymoon period, Merkel’s time in office came to be defined by a continuous thread of unprecedented turmoil not of her making but which required her to act nonetheless. Her first term was dominated by the U.S. subprime-led banking meltdown and subsequent global recession, which led straight into the crisis in the euro area spreading from Greece that rocked her second term.

Greece was admitted to the euro in 2000, the same year that Merkel became the leader of her party, swapping the untested European currency for the drachma which had been in use since long before the age of Homer or Alexander the Great conquered the known world. Once inside the euro club, from January 1, 2001, the country went on a spending spree it could not afford. State outlays on infrastructure soared in the run-up to the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens, matched by a record surge in consumer spending, and by late 2009, as a new Greek government was elected and Merkel began her second term, the bill was overdue. What came to be known as the sovereign debt crisis erupted, rippling out from Greece across the 17-country euro area. Financial markets took fright at the state of the region’s finances and started to push up the rates governments paid to borrow to unbearable levels, forcing Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Cyprus to seek international bailouts and bringing down governments across Europe as voters protested spending cuts and tax increases. Investors betting on the euro’s demise were pitted against politicians determined to stop it from happening, chief among them Merkel.

A scientist by training whose defining trait is caution, Merkel was forced to look beyond just Germany’s interests and to assume leadership in Europe. Thrust to the fore of policy making, she stepped up, slowly but with growing determination, to defend the euro she saw as the glue holding together the European Union (EU) that had been forged out of the ashes of war to stop the continent ever again descending into conflict. But how did the chancellor who came to office pledging to govern by means of many “small steps” come to take on the role of European savior? And what would the rest of Europe make of her prescription for Europe’s ills?

When she assumed the German chancellorship, Merkel took the helm of Europe’s biggest economy when it was struggling to adapt to the challenges of globalization. Unemployment had reached a postwar record of 12.1 percent eight months previously, in March 2005, growth was an anemic 0.7 percent compared with an average 1.7 percent for the euro area – Greece recorded 2.3 percent – and Germany’s budget deficit was poised to breach EU limits for the third straight year.2 The EU’s biggest wave of enlargement to date had brought 10 countries predominantly from the East into the bloc the previous year, including economically dynamic entrants such as the Baltic States and the regional powerhouse, Poland. Far from being Europe’s dominant player, a decade and a half after German reunification in 1990 the continent’s most populous country was playing catch up.

Germany was riven politically as well as economically after Merkel’s predecessor, Gerhard Schröder, had split with the U.S. over his refusal to join the 2003 invasion of Iraq. His program of far-reaching labor-market and welfare reforms had prompted street protests and divided his Social Democratic Party, even if Merkel had aligned her Christian Democratic bloc behind the measures. Yet Merkel was unable to capitalize on the situation and beat Schröder by a single percentage point in the 2005 election, limping into power at the head of an unwanted grand coalition with his party as governing partner.

As she prepared to contest elections in the fall of 2013, Merkel presided over Europe’s predominant country, with unemployment near a two-decade low and a budget close to balanced. Courted by prime ministers and presidents from across Europe who sought to win her over to their side, her policy stances were those that mattered most, her example the line hard to ignore. She had become Europe’s indispensable leader. So how did Merkel turn the continent’s most populous country around? What qualities did she bring to the post of chancellor that united a majority of Germans behind her? More than that, how did she position Germany as Europe’s foremost country, so much so that traditional allies including France, Italy, and Spain grew resentful of her methods and some in Greece, Ireland, and Portugal even questioned her motives?

The answer lies in large part with the evolution of the crisis and how Merkel brought the rigor of scientific analysis she’d learned in the physics laboratories of East Berlin and Leipzig to problem-solving of an economic and financial nature. Through trial and error, she edged her way forward, often to the dismay of her European peers and the exasperation of global partners. The German public, however, liked what they saw; polls consistently showed that they overwhelmingly backed her cautious stance, toward aiding banks in 2008, on measures to kick-start the economy in 2009 and above all on her handling of the debt crisis from 2010 onward. Throughout, she refused to be Europe’s unconditional paymaster.

Merkel’s response was to impose limits on aid and demand strict conditions in return, foremost among them budget cuts and deficit reduction to tackle what she saw as the root causes of the debt crisis. As she pushed a wary Europe to adopt the ways of Germany’s highly competitive economy, Merkel stirred up old enmities and became the fulcrum in a clash between European and U.S. economic values. Her prescription exposed a fault line with U.S. officials who urged the deployment of more firepower to fight the crisis and greater burden sharing by Germany, while the austerity she advocated exacerbated a surge in unemployment to record levels in countries such as Greece and Spain and risked deepening the economic slump. Standing out in front as those who challenged her answers fell by the wayside, Merkel’s means of defeating the crisis brought Europe to a crossroads. She was demonized in the Greek press as a jackboot-wearing Nazi hell-bent on reducing Greece, suffering the worst economic downturn since the war, to the status of a German colony.

Dispensing with caution for once, Merkel’s visit to Athens in October 2012 was intended as a riposte and a tangible show of solidarity for the Greek people. The German government insisted it was a “normal visit,” but it was clear she was entering the lion’s den. The New York Times called Athens “the most hostile territory in Europe” for the chancellor.3 Police were drafted from across Greece as some 40,000 protesters gathered on the streets to show their rejection of the European leader they regarded as the chief cause of their misery. Merkel, heavily guarded, came with no promises of additional aid, no pledge to ease the terms of Greece’s bailout loans, nothing other than a message of support. “I believe that we will see light at the end of the tunnel,” she said beside Prime Minister Antonis Samaras. “I want Greece to stay in the euro.”4

After assessing the alternatives, Merkel took the political gamble of her life and decided to stand by Greece and save the euro – but on her terms. In doing so, she garnered plaudits and criticism for her path to resolving the turmoil. As the biggest paymaster, her status as de-facto leader of Europe was undisputed, yet with resentment of her newly assertive Germany growing, it was far from clear whether the rest of Europe was prepared to share the journey to her final destination. Merkel acknowledged that her recipe for addressing the problems of the euro region through austerity and painful reform could raise hackles in other countries. But she saw that as one of many climbs to be surmounted on the way to a fitter Europe better able to compete on the global stage. “We have to be a bit strict with each other at the moment so that in the end we are all successful together,” Merkel said in November 2012. “I think it’s better to try and tell the truth among friends and then continue to show solidarity with one another.”5

As she concentrated on Europe, Merkel’s domestic agenda was swept away by crisis. From March 2010, when she delivered her first speech to the Bundestag on Greece, through the end of 2012, Merkel addressed the full plenary session 24 times: two of her speeches focused on energy and the decision to abandon nuclear power in favor of renewables, and one on Germany’s contribution to the military mission in Afghanistan; the other 21 dealt with aspects of the euro crisis and its ramifications for Germany and Europe.

Investors, economists, and political analysts hung on her every speech and policy twist as she honed her strategy to defend Europe and save the euro. Yet the chancellor has remained an enigma to many, her driving forces often misunderstood both in and outside Germany. A political outsider because of her roots, Merkel and her decision making remains opaque because of her Eastern habits such as a preference for doing her negotiating behind closed doors, turns of phrase that even Germans find hard to decipher and a dislike of sound bites. For Merkel, the European debt crisis centered on Greece became the crucible of her chancellorship, dominating her second term and helping to determine whether she served a third. Going forward, her choices will decide the success of Europe’s experiment to leave war behind, preserve its welfare states, and become the world’s most competitive economy. Where is she going? If she wants to, using Germany’s returned strength, Merkel has unprecedented leverage to take Europe in whichever direction she chooses.

Notes

1. Merkel speech on EU Danube strategy, Regensburg, November 28, 2012: http://www.bundeskanzlerin.de/Content/DE/Rede/2012/11/2012-11-28-merkel-donau.html.

2. Eurostat table of EU country GDP: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=tec01115.

3.http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/10/world/europe/angela-merkel-greece-visit.html.

4. Brian Parkin and Marcus Bensasson, “Merkel Urges Greece to Maintain Austerity to Stay in Euro,” Bloomberg News: October 9, 2012: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-10-09/merkel-s-athens-message-seen-directed-at-german-greek-audiences.html.

5. RTL interview, November 10, 2012: http://www.bundeskanzlerin.de/Content/DE/Interview/2012/12/2012-12-11-bkin-n-tv.html.

Chapter 2

Revelation (Five Minutes to Midnight)

Angela Merkel stepped out of her Audi A8 and on to the red carpet at the Cannes conference center to be greeted by Nicolas Sarkozy flanked by French Republican Guards in white breeches and ceremonial plumed helmets, their sabres held aloft in salute. For all the pomp, the mood on the French Riviera in November 2011 was far from celebratory: Merkel shook her head and Sarkozy raised his hands in a gesture of exasperation as they met. It was Greece again.

Europe was two years into the sovereign debt crisis that had emerged in Greece and was rippling through the euro area. Governments were toppling as borrowing costs soared, dividing the region into a relatively healthy northern core anchored by Germany and a weaker periphery that ran in an arc from Ireland to Spain and Portugal, through Italy to its focal point, Greece. Each step of the fight to beat back the contagion only ever calmed financial markets for a matter of weeks or less before the flames reappeared somewhere else. Two bailouts worth 240 billion euros for Greece alone, almost the equivalent of its entire annual gross domestic product, the promise of debt relief, enrolling the expertise of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) alongside a 440 billion euro European rescue fund had failed to stop the crisis in its tracks. Now Greece’s Prime Minister George Papandreou had given a televised address in Athens announcing his intention to hold a referendum on the latest round of measures approved by European governments to aid his country. A “No” vote would unravel what progress had been made and cause fresh waves of uncertainty to crash over the euro area, throwing the future of the single currency further into doubt. Merkel, as the leader of Europe’s dominant economy, was first in line to stop that from happening.

She and Sarkozy met in Cannes on the eve of a Group of 20 summit of world leaders to decide the next move in their campaign to save the euro and defend European unity. Over two days in the Cannes conference center at one end of the palm-lined Boulevard de la Croisette, Merkel joined with Sarkozy to threaten Greece with defenestration from the euro and browbeat Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi into the humiliation of allowing outside monitoring of his country’s economy. Within a week of being publicly cut loose, the Greek and Italian leaders lost what residual support they had and stood down, twin victims of the crisis. It was regime change by alternative means. Cannes, the Riviera town that hosts the eponymous film festival, was the moment that all strands came together in the crisis, and Merkel was the principal actor.

• • •

The Greek economy was on a life support system, dependent upon international aid as it faced a fifth straight year of recession. Public backing for Papandreou’s government had collapsed as jobs and spending were slashed in a bid to wrestle down the biggest debt load per capita in the 27-nation European Union,1 measures that were demanded in return for financial help under the terms of Greece’s rescue deal. Papandreou’s way out was to call a referendum in a bid to lance the boil and win some space to press on in the hope that signs of progress would emerge to alleviate the anger at home. His problem was that he failed to inform either his European partners or his own ministers before he made the announcement. “His behavior was disloyal,” said Luxembourg’s Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker, who also headed meetings of finance ministers of the euro countries, a role that gained in importance the longer the crisis persisted. “We would like to have been told.”2Le Monde reported that Sarkozy was dismayed by the revelation. The G-20 summit hosted by France was meant to set the stage for his campaign for a second term. Sarkozy planned to show a united European front and win agreement from world leaders for a global effort to restore confidence to financial markets that were losing faith in Europe’s ability to tackle the malaise at its heart. He was going to be photographed with Chinese President Hu Jintao and sign autographs with U.S. President Barack Obama as the crowds cheered. “History is being written in Cannes,” read the G-20 banners going up around the town. Now his plans were threatened by Greece, and it wasn’t even a member of the G-20 club.

In Berlin, Chancellor Merkel learned of the referendum at 7:20 p.m. on October 31 and took a moment to consider her response. She called Sarkozy and the two decided to summon Papandreou to Cannes to explain himself. They also agreed to halt the next aid payment to Greece until the referendum was cleared up, money that Greece desperately needed to pay its bills. At 7:15 a.m. on Tuesday morning, German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble called his Greek counterpart, Evangelos Venizelos, in the Athens hospital where he was undergoing treatment for stomach pains and told him of the decision. Finance ministers from the other euro countries rubber stamped the suspension of aid within 90 minutes. Greece was effectively in limbo until Merkel and Sarkozy decided what to do with Papandreou. “Merkel and Sarkozy were upset because they felt they were betrayed,” said Xavier Musca, Sarkozy’s chief economic adviser and G-20 coordinator at the time. “They also felt Papandreou was not reliable, because they had spent one night with him discussing everything, and then he decides to do something he never talked about.”3

The night in question was a 10-hour crisis session of European leaders in Brussels the previous week on October 26–27 again dominated by Greece. Papandreou’s maneuvering was particularly galling for Merkel and Sarkozy because they had sat up half the night to negotiate a deal aimed at saving Greece, the second in almost 18 months. Their backing had secured agreement on a 130 billion-euro bailout for Greece crafted with the IMF on top of a 110 billion-euro rescue agreed in May 2010. They had personally intervened with the banks’ representative, Charles Dallara of the International Institute of Finance, summoning him from his hotel that night to accept losses of 50 percent on Greek government debt held in private hands. When he resisted, he was told the alternative was to allow Greece to go bankrupt, after which the banks would in all likelihood receive nothing back on their investments.4 The same summit also forged a plan to increase Europe’s rescue fund for any future countries that went the way of Greece to 1 trillion euros, as well as compelling banks to raise the amount of money they held in store to absorb financial shocks. Taken together, it was a package that promised to finally snuff out the flames of financial contagion that were spreading across Europe while putting a lid on the source of the conflagration: Greece. At the summit’s close, Papandreou personally thanked Merkel and Sarkozy for their efforts. “This agreement gives us time,” he said. “Tens of billions of euros have been lifted from the backs of the Greek people.” Even Merkel departed from her characteristically restrained rhetoric. “I am very aware that the world’s attention was on these talks,” she said at a press conference after 4 a.m. as the summit ended. “We Europeans showed tonight that we reached the right conclusions.” It took one weekend for Europe to demonstrate its inherent capacity to shoot itself in the foot. Greeks were in open rebellion and opposed putting their country any more at the mercy of its international creditors. They wanted nothing do with a policy that promised to inflict yet more deprivation on a population already on its knees. Papandreou, having successfully negotiated for the debt burden to be eased, returned home to be greeted as a traitor.

A snap poll in Greece taken after the EU summit floated the idea that the measures agreed should be put to a referendum, with 46 percent saying they would vote against. More than seven in 10 still said they wanted to stay in the euro. With his majority whittled down to 153 seats in the 300-member parliament, Papandreou felt he needed to resolve that contradiction and regain democratic legitimacy. A plebiscite fit the bill, even if for Greece as well as for the rest of Europe the prospect of a referendum created a whole new set of unknown factors. International financial markets, already highly strung after months of bombardment by the crisis centered on Greece, were quick to offer their verdict. On Tuesday, November 1, the day after the referendum plan was announced, Germany’s DAX lost 5 percent, France’s CAC 40 Index dropped 5.4 percent and Italy’s FTSE MIB Index sank 6.8 percent. U.S. stocks were hit and shares in Asia tumbled. National Bank of Greece plunged 15 percent, sending its share price to its lowest since 1992.5 Fitch Ratings said the referendum “dramatically raises the stakes for Greece and the eurozone,” increasing the risks of a “forced and disorderly” default. What that meant for the rest of the eurozone was incalculable, but the implications were dire. According to an estimate by Natixis, if Greece left the euro it could cause an additional 16.4 billion euros in net losses to French banks alone, with Sarkozy’s government left to fill the hole.6

Papandreou’s proposal “surprised all of Europe,” the French president said on November 1. “The plan adopted unanimously by the 17 members of the euro area last Thursday is the only possible way to resolve the problem of Greek debt.” In a joint statement issued the same day, he and Merkel said the package of measures agreed in Brussels was “more necessary than ever today.” EU President Herman Van Rompuy and EU Commission President José Barroso raised the pressure on Papandreou to stop the deal from unraveling. “We fully trust that Greece will honor the commitments undertaken in relations to the euro area and the international community,” they said. Italy, the euro area’s third largest economy, was meanwhile coming under threat. That night in Rome, on the eve of the G-20 summit and after a day in which Italy’s government borrowing costs climbed to the highest relative to Germany since before the advent of the euro, Prime Minister Berlusconi called an emergency meeting of his Cabinet.

• • •

With the stage set for Cannes, Merkel and Sarkozy arranged to meet Papandreou at the film festival center facing the harbor filled with extravagant super-yachts. The Greek premier arrived a few hours after Merkel. This time there was no guard of honor. The EU’s Barroso and Van Rompuy attended the November 2 meeting along with the eurogroup head Juncker, IMF chief Christine Lagarde and the finance ministers of France, Germany and Greece. Papandreou arrived in Cannes bolstered by his Cabinet’s unanimous endorsement for his referendum plan, for all the residual doubts. There was still no word on the question to be put to the people. “The referendum will be a clear mandate and strong message within and outside Greece on our European course and our participation in the euro,” Papandreou told his ministers that morning before leaving for France. Already having to fend off calls for new elections from the opposition New Democracy party led by Antonis Samaras, the Greek premier said the question was not one of his government or another government: “The dilemma is yes or no to the loan accord, yes or no to Europe, yes or no to the euro.”

Merkel and Sarkozy wouldn’t allow Papandreou the luxury of choice. The meeting, in one of the many rooms off the main conference hall, was explosive. Merkel, who was visibly “very upset,” according to Musca, saw it as time to face up to some unpleasant truths that had been avoided for too long. She and Sarkozy confronted Papandreou and berated him for presenting them with a fait accompli. Yes, the Greek people had made sacrifices, but the country as a whole was not an innocent party in the crisis of confidence sweeping the eurozone. They told him his planned ballot had placed the entire euro area at risk, and Europe’s biggest powers could not let the single currency be wrecked by one country. Suspecting him of trying to wriggle out of the commitments he made one week previously in Brussels, they handed him an ultimatum: hold to the agreement or wave goodbye to 8 billion euros in international rescue funds he needed to pay Greece’s bills. If he must hold a referendum on the outcome of what was decided, then it could be about one thing only: Greece’s future membership of the euro; in or out, they were prepared to let Greece go and risk the consequences. Sarkozy and Merkel dictated the timing and the content of Papandreou’s referendum, and spelled out the consequences of its outcome. The vote had to be brought forward to December to get it out of the way, removing a source of uncertainty as soon as possible. It could address Greece’s future in the euro only and not any aspect of the country’s bailout terms. Furthermore, there would be no money for Greece until the result was known. Sarkozy held a press conference after the meeting and said that not one cent would flow to Greece in the event of a “No” vote. It was all or nothing. Papandreou, presented with no alternative and his referendum eviscerated, accepted their terms. Publicly humiliated, he returned to Athens to face a confidence vote in parliament.

The G-20 started the next day, Thursday November 3, with a discussion of Greece. Underscoring the global ramifications of one small country’s travails, a television set was brought into the main meeting room to allow leaders to watch the debate in the Greek parliament broadcast live on BBC World. As he addressed the main chamber in Athens, world leaders and the assembled press of more than 20 nations gathered around television screens to watch Papandreou. His majority dwindling further to two, the prime minister made a plea for a government of national unity to overcome the country’s epic problems. Political consensus, with the opposition coming on board to secure outside aid and help the transition through this unprecedented situation, would remove the need to ask the public’s backing for the deal struck in Brussels, he said. Venizelos, his finance minister, was more direct: Greece wasn’t going to hold a referendum. The vote scrapped and his attempt to seek legitimacy for the deal in tatters, Papandreou offered to stand aside to help the formation of a national unity government. He went on to win the confidence ballot by 153 votes to 145 votes after promising his own parliamentary group that he would go. His last-ditch gamble had failed. Politically he was a spent force and he resigned the following week on November 11, nine days after Merkel and Sarkozy lost patience with him. Papandreou, who compared Greece’s path out of the crisis to Homer’s classic tale of Odysseus’s 10-year journey back to Ithaca, foundered at sea without reaching home. Merkel, acting with Sarkozy, helped seal his fate.

• • •

If Greece could trigger the biggest two-day decline in global stocks in almost three years, as Papandreou’s referendum flip-flop had done, then events in Italy had the potential to cause even more carnage. Italy, the third biggest economy in the euro, with domestic output almost 10 times that of Greece, was becoming a worry to Merkel and Sarkozy alike. They’d already confronted Berlusconi on October 23 at a previous EU summit and told him to follow through on his commitments. Asked at a joint press conference what they’d said to Berlusconi then, Merkel and Sarkozy looked at each other for a moment, then laughed. Trust can only be regained by Italy assuming its responsibilities and taking credible steps for the future, Merkel said, dictating to Berlusconi what must be done. “Italy has great strengths but Italy also has a very high overall debt level, and that has to be credibly reduced,” she said. “That, I think, is the expectation on Italy.”7 On the eve of traveling to Cannes, with Italian government borrowing costs soaring, Berlusconi had promised to enact emergency measures in a budget bill to be passed that month including raising the retirement age, easing rules on firing workers, and accelerating state asset sales. Yet having given the wrong signals to markets in the past, Berlusconi was unable to give investors the assurances they wanted on Italy’s policy direction to merit an easing of the government’s costs of borrowing. Germany and France were pressing the Italians in private to announce budgetary measures before it was too late. Powerless to change his course and unable to have him fail to meet his commitments, the French and German leaders summoned Berlusconi to a room in the conference center on Thursday morning. As with Papandreou, they gave him an ultimatum: this was not a discussion about voluntary measures. Sarkozy and Merkel told Berlusconi that solving Greece was one thing, dealing with Italy a problem of a different magnitude. Unless he gave an immediate signal demonstrating that he was aware of the gravity of the situation, he was lost. Now that the fire of contagion was in Italy, the whole eurozone was at risk of implosion, they said: Do something about it. When Berlusconi said that he had always done the right thing by Italy, Merkel and Sarkozy told him markets didn’t share that faith. He needed to do something quickly to regain market confidence if he was to give Italy a chance of surviving the crisis. Boxed in, Berlusconi agreed to have the IMF send outside monitors to assess Italy’s budget. In a statement issued the following day at the close of the G-20, Christine Lagarde welcomed “Italy’s decision to invite the IMF to intensify our surveillance and monitoring work, to help support the major steps being taken by the government on both fiscal adjustment and structural reforms.” It was too little too late. Battered by the markets that drove Italy’s borrowing costs to fresh records, Berlusconi announced his resignation on November 10.

• • •

For Merkel, whose position as Europe’s principal decision maker was cemented six months later when she lost her ally Sarkozy in France’s presidential election, the moment of truth for the euro area was the latest incarnation of financial crisis that had rocked her chancellorship almost since the beginning. Merkel was just 18 months into office when she was confronted with the worst global financial meltdown in living memory. She set about resolving each stage of crisis for which there was no playbook – in the banks, the economy, and as a result of euro countries’ debt loads – and she learned along the way. Catapulted to the forefront of European policy making during the euro trauma, it came to define Merkel’s chancellorship even as she struggled for a solution. Some leaders, like Papandreou and Berlusconi, collapse and fall victim to crisis; others like Merkel flourish. Lambasted for delaying, for backtracking, and for refusing to commit more resources to the crisis fight, Merkel showed at Cannes that she can suddenly be decisive, brutally so.

The source of her resoluteness lay four months previously in the summer of 2011. Markets were plunging globally with the realization that Europe’s common efforts to help Greece had failed and the bailout program wasn’t working, spelling trouble for the rest of the euro area. An EU summit on July 21 had agreed on the second Greek bailout of 130 billion euros among a package of steps that included expanding the powers of the European rescue fund and easing the terms of emergency bailout loans awarded to Portugal and Ireland. Merkel also quietly dropped plans to enlist banks and other investors in helping to pay for the fallout of crises once a permanent rescue fund was set up in 2013, after criticism from the European Central Bank (ECB) and the U.S. that forcing the private sector to accept losses on their investments would worsen the situation and could tip the euro area over the edge. However, the summit still backed a German-led push for a restructuring of Greek debt, without shoring up Spain and Italy against contagion, sowing the seeds of the next bout of trouble. As early as April 2011, Germany had signaled its willingness to impose losses on Greece bondholders in the face of pledges by Papandreou to avoid such a situation. Werner Hoyer, Germany’s minister for European affairs, said that a so-called haircut on the debt held by investors “would not be a disaster.”8 By broaching a previously taboo subject, Germany was setting itself up for a widening of the crisis for political reasons. The market response was swift: the turmoil spread and started to infect core euro countries, with the interest rates paid by the Spanish, Italian, and even French governments climbing steeply. ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet instructed the central bank to step in and start buying Spanish and Italian government bonds in a bid to impose some calm and stop the situation from spiraling out of control.

Until that summer, Europe’s leaders had focused on tackling small, peripheral countries: Greece, Ireland and Portugal, together worth some 6 percent of euro area gross domestic product (GDP). The meltdown showed the crisis had moved to the core, marauding Italy and Spain, jointly representing more than 25 percent of the euro area’s output, and lapping at the doors of the region’s linchpin, Germany. Forced to confront the evidence that the entire region was facing an existential threat, Merkel shifted her focus: she decided she had to save the euro and to take Europe with her. As early as May 2010, she had expressed her conviction that “our Europe will overcome the present crisis of our common currency.” Now it was time to act. Up to that point, Merkel insisted there were no innocent victims of the crisis, that countries had brought the market reaction upon themselves, whether through greed, corruption, or ineptitude. As Italy was sucked into the maelstrom despite a budget deficit of 3.9 percent in 2011 – just 0.9 percentage points outside EU limits and lower than France’s9 – she had to question that assessment. Markets were starting to price in a 98 percent chance of a Greek default, yet Merkel concluded it was impossible to calculate the impact of a “disorderly insolvency” on the wider euro area. Merkel told a closed meeting of leaders of her parliamentary group as they gathered in the Reichstag on the last day of August after the summer break that she would not go down in history as the person who wrecked the euro.10 With a lack of drama typical of the chancellor, she announced her decision to the world two weeks later on a regional radio station serving the greater Berlin area. “The top priority is to avoid an uncontrolled insolvency because that wouldn’t just hit Greece,” Merkel said in an rbb Inforadio interview on September 13. “Everything must be done to keep the euro area together politically, because we would very quickly face a domino effect” otherwise.11

The U.S. was quick to recognize the shift in Merkel’s thinking as a turning point for the global economy. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner appeared on CNBC the following day and praised Merkel’s comments as an acknowledgment that Europe’s crisis response to date had been “behind the curve” and that more had to be done. “And I think it’s important that you saw the Chancellor of Germany say yesterday – Angela Merkel say yesterday they are absolutely committed, and they have the financial capacity and the economic capacity to do what it takes to hold this thing together,” Geithner said.12

Merkel had until then been prepared to make it easy for Greece to leave the euro, perhaps offering guarantees of an early return to the currency under certain conditions, but the decision had to come from Greece. There was no mechanism to expel a country, however wayward, and to do so without the Greek government’s agreement would have spelled meltdown. With the realization that this was a place she could not go, Merkel swung behind Greece. Gone was the chastising language threatening sanctions on deficit “sinners” and in its place was encouragement to meet targets on the road to recovery. “We want a strong Greece in the euro area and Germany is ready to offer all kinds of help that is needed,” Merkel said after meeting with Papandreou in Berlin two weeks later, on September 27, 2011. Having finally acknowledged the stakes, Merkel made a choice to hold the eurozone together. That was why Papandreou’s referendum so incensed her. It also explained Merkel’s reconciliation with his successor, Antonis Samaras, after snubbing him for more than a year and a half. As the fall of 2011 drew closer, she had to rebalance German interests against Europe’s future, pitting her domestic reality against the wider effort to save Europe’s postwar unity. For a chancellor known for her love of weighing the evidence before settling upon her preferred option, it was decision time.

• • •

French philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy, interviewed in the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung in November 2012, said the fact that Greece and Italy – the cradles of European civilization – were among the countries worst affected by the crisis showed how it had reached “to the very fundament of European existence.” The crisis had overcome Europe’s “memory, everything that makes up its basis and origins, its soul, its grammar,” he said.13