7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

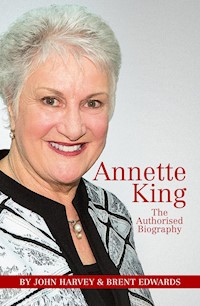

- Herausgeber: Upstart

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Annette King is New Zealand's longest-serving women MP — 1984-2017 less three years in the wilderness from 1990-1993. In her 30 years in Parliament, she spent 15 in government (10 as a cabinet minister) and 15 in opposition. She is a former deputy leader of the Labour Party, and held a number of senior cabinet portfolios. This book will take a dual approach to her life and political career. Annette's career embraces a tumultuous time in New Zealand politics and Labour politics . . . Rogernomics and Lange's independent foreign policy; the 1990s and advent of MMP; the refinement of Rogernomics under Ruth Richardson etc; the rise and nearly fall of Helen Clark; the Clark government (where Annette served as Health, Food Safety, Police, Transport, Justice and Racing Minister); the subsequent 9 years of difficult and troubled opposition for Labour; and eventually the rise of Jacinda Ardern. Annette played pivotal roles in all these eras, often as the peacemaker or as Auntie Annette. She became a mentor for many of the prominent members of the Ardern government and, of course, played a lead role in the 2017 election campaign and subsequent negotiations. The book gives rein to Annette's voice, but also features other prominent figures including Jacinda. The book opens with the 2017 campaign.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand

ISBN

EPUB: 978-1-988516-78-3

MOBI: 978-1-988516-79-0

An Upstart Press Book

Published in 2019 by Upstart Press Ltd

Level 4, 15 Huron St, Takapuna 0622

Auckland, New Zealand

Text © John Harvey and Brent Edwards 2019

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted.

Design and format © Upstart Press Ltd 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Designed by CVD Limited (www.cvdgraphics.nz)

Cover image: Neil Mackenzie

Almost all of the illustrations for this book were sourced from Annette King’s private collection. Most are personal photos, but some have obviously been presented to Annette by various photographers and do not carry copyright stamps. Any photographer and/or organisation claiming copyright should contact the publishers directly.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the following people (in alphabetical order) who agreed to be interviewed for this book, or otherwise helped in its preparation: Jacinda Ardern, Steve Chadwick, Helen Clark, Clayton Cosgrove, Michael Cullen, Mary Day, Pauline Eales, Lloyd Falck, Phil Goff, Darren Hughes, Ray Lind, Andrew Little, Steve Maharey, Trevor Mallard, Judy McGregor, Mike Moore, Maggie Morgan, Jenny Newby-Fraser, Geoffrey Palmer, Amanda Parsons, Trish Ranstead, Jenny Rose, Jim Sutton, Liz Tennet, Paul Tolich, Fran Wilde and the many others who provided factual details when we needed them.

Contents

Prologue

A small-town girlThe awakening yearsWarm glow of victoryRogernomics and disintegrationFun and reward in Palmerston NorthBack in the House in troubled timesThe ousting of MooreTroubles for ClarkOn the cusp of government againBack in the BeehiveScope of practiceA happy officeAchievements

Photo Section

From scoliosis to folatePolicing: lots of highs — and one serious lowLabour in the doldrumsAnnette at centre of victoryA ‘feminist’ MPFamily and friendsAnnette goes but Labour is back

Epilogue

Prologue

The two women could not have been more excited in the early evening of 19 October 2017.

One was on the verge of becoming Prime Minister; the other was stepping down from politics after a career as the longest-serving woman Member of Parliament.

Labour had not exactly recorded a historic result in the 23 September election, and it was still unclear just how strong a position it was in to negotiate to form the next government. But its election-night result of nearly 36 per cent was well beyond the expectations of just a few weeks earlier when it was struggling in the opinion polls around 23 to 25 per cent.

Jacinda Ardern, thrust into the leadership just seven weeks earlier, was standing on the stage at Labour’s election-night rally almost talking down her supporters’ expectations. Annette King, too, was disappointed on election night despite Labour recording a vote much stronger than she could have dreamed of just two months earlier.

But a few weeks later, after the special votes had been counted, Labour’s vote went up to 37 per cent and it picked up another seat, as did the Greens. It meant those two parties, plus New Zealand First, had a combined 63 seats in the 120-seat Parliament. When those numbers came through, Ardern and Annette could again seriously consider the prospect of Labour forming the next government.

Then after days of negotiations with New Zealand First and the Greens, while New Zealand First was negotiating separately with National, Winston Peters finally strode into the Beehive theatrette to announce his party was going into coalition with Labour.

Annette King, former deputy leader, minister, electorate MP, party peacemaker and now mentor of Labour’s new leader, could leave politics with Labour back in power after nine years of drift and uncertainty.

Everywhere on the campaign trail Annette had been immediately behind Jacinda Ardern. When Ardern was made leader, one of the first things she did was decide King should accompany her throughout the election.

For Ardern, Annette was a mentor and a role model, not just in politics but life.

‘Annette had this way of being incredibly committed to what she did, totally focused but also balanced in her life. So you could see that she still enjoyed politics and I wondered if that came from the fact that she had this balanced life where she worked hard but also spent time with her family. Whenever she talked to me about how life was going, it wasn’t just how’s your portfolio, how’s the electorate and how’s the campaigning? It was also, you know, how’s your personal life, what’s your living situation now, who are you seeing?’

Ardern says Annette cares and she knows that surviving in Parliament and politics is more than about the job.

‘Often whenever I speak to women’s groups about the role of mentors I always say personally for me how important it was having a mentor who cared about my life beyond my work life. [It] was really important to me because that [work] was never how I was going to define all my happiness. So that probably made a big difference to the relationship we had.’

Annette might have retired from politics in 2017, but she left a strong legacy for Labour as it reclaimed the Treasury benches it had lost nine years earlier.

Those had been tough years as Labour changed leaders repeatedly and seemed unable to find the unity of purpose which had served it so well from 1996 to 2008. But Annette, who had been through earlier bad times with the party, did not wilt.

She provided a stability to the party it badly needed as it lurched from crisis to crisis. In the end she was to make some of the pivotal decisions — personally and for the wider party — that put Labour miraculously back in the position to form a government after the 2017 election.

New Zealand and Labour’s longest-serving woman MP handed on the baton to a new generation of women leaders. And the woman who considered Annette her mentor became Prime Minister.

For Annette, there could hardly have been a better time to walk away from politics.

Chapter 1

A small-town girl

As a minister in the Helen Clark Labour Government, Annette King returned to her home town of Murchison to ride a horse. In doing so, the idea was to recreate the first time her photograph appeared in a national publication. That was what Murchison had planned anyway. Somewhat less according to plan, however, she came off the horse and broke her foot.

Broken foot aside, she has few memories of her home town that are less than positive or happy.

‘I’m a small-town girl. Murchison was a small community of 600 people. There was lots of freedom to roam, lots of nosy neighbours, everyone knew everyone. Sunday visits and afternoon teas. The movies on Saturday nights. I was the middle child and a sickly child. I was born small and was unwell as a child. When I was four and five, I was sent to live by the seaside with my aunt in Motueka. It must have done me a lot of good because I have had rude good health ever since. I also had some problem with my feet. I used to have to wear boots with orthotics to correct my feet. I was also a skinny kid. In fact, my name was Skinny Robinson.

‘But, boy, did I have a good childhood. My parents were working. They only had wages. They built their own home. My grandparents lived next door so we had an extended family for most of my childhood. Mum went back to work, when I was about 12, at the Post Office, which was just down the road. Everything was so close that my older sister Raelene used to cook tea for us all, and one of us would ride our bike down with Mum’s tea on a plate to the Post Office. She was in the telephone exchange. Knock on the door, she would open it, and I’d pass through her dinner. You’d come home from school and get on the phone (a party line), and Mum would answer, and you would give her your girlfriend’s number, and your mother would say, “Don’t be too long on there because you have to peel the potatoes.” And after a certain time, Mum would come across the line, and say, “Hang up now, you have had long enough.”’

Annette’s grandparents on her mother Olive’s side — Ned and Jessie Russ — lived next door to her till Jessie died. Her other grandparents — Granddad Robert Robinson and Nana Ruth Woodford Robinson — lived just outside the town. ‘My grandfather Ned came and lived with us when my grandmother died. Ned Russ was a wonderful old granddad. That’s one of the things I really valued about my childhood, having my grandparents so close. When my grandmother was alive, she used to make porridge for us every morning, and yell out through the kitchen window that it was ready. She’d pass the pot to us. Granddad taught me poetry. He loved his poetry. Banjo Paterson’s “The Man from Ironbark” or “Mulga Bill’s Bicycle”.’

Annette’s heritage on both sides of her family was rich and loving, and strongly imbued with Labour values, even if Ned Russ later in life became what her father Bill called ‘a two-bob Tory because he had two bob in his pocket from the pension’. Before they shifted into Murchison itself, Ned and Jessie Russ had a small farm outside the town. ‘They were on it right through the Depression and they had a lot of what they called swaggers coming in for food. During the Depression he worked on the roads because there was nothing coming in from the farm, and then they shifted into Murchison, and he joined the Department of Public Works.’

Her father Bill’s family was not only diverse but strongly rooted in the Labour tradition. The Robinson family and another family called the Paces came from Jarrow, the Tyneside town that will forever be associated with the famous march in the 1930s against poverty and unemployment. The Robinsons and the Paces intermarried, and the family name Pace survives to this day as one of Annette’s grandson William’s Christian names. Pace was the name of one of the ancestors who married a Robinson. Bill’s father Robert Robinson, who was born in England in County Durham, came out as a young man with his father Matthew. The Robinsons had a small farm at Owen River and Granddad Robert worked in the Owen River coalmine. Annette’s father also started work in that coalmine. The Robinsons lived about 15 kilometres away from the town, and Annette saw a lot of her grandmother from the time she was five. ‘I used to spend holidays with her. After Granddad died she went to live with her daughter in Motueka and had her own little cottage. Nana Robinson was the granddaughter of John Jacob Appoo, my Sri Lankan great-great-grandfather, and the first Ceylonese settler in New Zealand. Nana Robinson’s mother was John Jacob Appoo’s daughter. John Jacob married an Englishwoman in England called Alice Hanley, and they came out to Nelson. They had two surviving daughters and one of them, Julie Euphemia, was my grandmother’s mother. Great-great-granddad died in the goldfields of Clunes in Victoria, Australia, and Great-great-grandmother came back to New Zealand with the two surviving daughters. My grandmother was born just outside Greymouth in Taylorville.’

The Russ family were among the first settlers in Nelson and were farmers in Waimea West. ‘I am related to Chris Finlayson and Chester Borrows through that line.’

But back to falling off the horse . . . if family were a crucial part of Annette’s Murchison years, so were horses.

‘I started riding ponies when I was about eight. My parents bought me a little pony called Robin, and then I became a competitive rider. In a town like Murchison you could afford it; it was something like 10 shillings a week for grazing fees. The horse and my riding became a major focus for the whole family. I competed in three-day shows like Christchurch and Nelson. When I outgrew the pony, it was handed on to [younger sister] Pauline, but she didn’t like the pony much. She and the pony would both go to sleep.

‘Raelene was scared stiff of horses so she didn’t ride, except one day she said she wanted to ride my horse, so I put her on the horse, whacked it over the backside, and let it go. She went round and round screaming. She didn’t fall off, but I don’t think she has forgiven me yet, just like she didn’t forgive me when she got her brand-new bike. She was so proud of it. She used to polish it, and I decided one day it was too wet and muddy to carry the hay over to the horse, so I got some hay and put it on the back of her bike, rode it over to the paddock and fed my horse. I then rode the bike back and chucked it in the shed. That was one occasion when we had very cross words.’

Annette was invited down to the Murchison School 120 years’ celebration. ‘I had ridden a horse side-saddle for the 80th when I had been at school. In fact, I got my photograph in the Auckland Weekly News in the shiny pages, dressed up in period costume riding this horse side-saddle. So they asked if I would ride a horse at the front of the parade 40 years later. [Husband] Ray came down with me, and I rode the horse, not side-saddle, at the front of the parade. I took the horse back to the paddock where there were lots of activities, like a show day, sideshows, merry-go-rounds et cetera. When I got back there, I thought, “I can still remember how to do this”, so I gave the horse a good boot, and thought I would ride it up to the end of the paddock and back. It was up a bit of a hill. Off I went at a gallop, and I don’t know what happened, but my foot came out of the stirrup, and the horse realised I wasn’t completely in control, and it spun around on four legs and it shot round. I flew out of the saddle and landed on the ground. The horse took off back to the gate. I was way up the top of the paddock. I stood up, and thought, oh my god, I can’t stand on this foot. But everyone could see me, so I walked back down to where the horse was, and by then my foot was swelling up. I had to go and make a speech and walk around all the sideshows. People were saying to Ray, she must be enjoying having a day off. Ray’s response to that was: “Day off? We got up at five in the morning to fly here.” Anyway, Ray took me up to the Murchison Hospital and they put a bandage around it. I came back to Wellington, and a few days later I went to have it checked because it wasn’t improving, and I had broken a bone. They couldn’t do anything for it.’

Annette was no stranger to broken bones. When she was MP for Horowhenua, one evening she came out the door of her little flat. ‘It was teeming with rain, and I was going off to speak to the Levin council, and I stepped on the painted steps of the flat, and my shoes slipped, and I took off and landed on my ankle. It went underneath me and I heard a crack. So I crawled back to the door because I couldn’t stand. I phoned my neighbours and they came over. I asked them to call up the ministerial car “because I want to go back to Wellington because I think I have broken it”. So a ministerial car came all the way up from Wellington, picked me up, and took me into Wellington Hospital. They put me in plaster, and I can still remember getting up the steps to my house in Evans Bay on crutches. It must have been a Thursday night, so I had the Friday, Saturday and Sunday at home with my foot up. On the Monday I got up, drove the car into Wellington, and got around on crutches for a week. At the end of the week I had to go back to hospital, and they said, now you have been resting all week with your foot up, haven’t you? I said no. They said, didn’t you read the papers we gave you, and I said no. I have always been frustrated that I missed out on that whole week when I could have done nothing. I was an undersecretary at the time. I had the plaster off six weeks later and a day later I flew to Paris to do a conference for Michael Cullen. Raelene came with me. By the time we got to London my foot was so swollen she had to get a wheelchair to push me off the plane.’

Fortunately, by the time she became health minister a decade or so later, she had developed a more responsible approach to her own health and everyone else’s.

Annette describes her childhood in Murchison as ‘lucky’. By that she means she was incredibly happy, surrounded by three generations of loving family and more or less successful or gifted at whatever she turned her hand to. Horse riding was the most notable example. ‘I was selected for the Nelson-Marlborough team to compete at the New Zealand horse championships in Hawera, and Mum and I went across in the ferry with the horse. I was probably about 13. There were four of us in the team. We had fundraisers for it. We had dances in Murchison. Mum played the piano for the dances. She had taught herself to play. She played all the dances including the Gay Gordons. The whole trip was a huge adventure. It was the first time I stayed in a pub. We stayed in the St George in Wellington. It was the first time I saw television. It was black and white. We travelled up to Hawera and competed. I didn’t come anywhere, but a charter planeload flew up from Murchison in a DC-3 to watch us. I have still got a lot of horse ribbons I won. I competed until my last year at school when I had to leave Murchison to go to Waimea College. I had been at Murchison District High and then spent one year at Waimea College. We sold the horse when I was about 16. About five years later when I was married to Doug and pregnant with Amanda, I read in the paper that my horse Dusky Boy was competing with the new owners at the Nelson Show. I went out to the show and went along all the stables. I found him. I said his name, and he turned round, came up to me and stuck his nose into me, just like he always used to do. The owner came along, and I said, can I have a ride. I was seven months’ pregnant, with a dress on. I climbed on the horse and cantered around the paddock at the Nelson Show.

‘There were so many good things about my childhood. I suppose I was the lucky one in the family because things just came my way. Apart from the horse riding, and the poetry, and winning cups for singing, I was also the first one in my family to go to university. First, I went to dental school, and then told my parents I was going to go to university extramurally, and they said what is that? There was one person in Murchison who had been to university and she had married a local. That was the sort of town it was.’

Annette left Murchison in 1965 and shifted to Christchurch to go to dental school, where she trained as a school dental nurse for two years. She also met her first husband Doug, an undergraduate student at Lincoln University, finishing his bachelor’s degree. Annette married Doug in 1968, and the couple shifted to Nelson where Amanda was born in March 1970. They returned to Christchurch for Doug to do his masterate at Lincoln, and when he completed that he was appointed as a horticultural advisory officer in Motueka. Later Doug got a job at Ruakaka in 1974, and he began work on his doctorate. They were in Hamilton from 1974 to 1981, and Annette, who had begun extramural studies while in Motueka, doing English and education papers from Massey University, was encouraged by Doug to continue part-time at Waikato University, studying politics and history. She completed her bachelor’s degree in 1982, having completed her post-graduate diploma in dental nursing the previous year.

The years in Waikato were formative for Annette in many ways, not least because of the lifelong friendships she developed at Knighton Normal School with teachers Jenny Newby-Fraser and Mary Day. The trio still cherish a strong bond more than 40 years on.

The second important event as such was the first real manifestation of her political instincts, making their appearance in her wholehearted embrace of a fair deal for dental nurses. Annette had come from a Labour family, of course. Her father Bill or Pops had begun work as a coal miner at Owen River when he was 13, leaving to begin his apprenticeship in the Post and Telegraph when he was 15. Olive’s family were Labour, but in later years when they retired, Ned Russ turned Tory. Annette can remember the rows between Bill and her grandfather. So Annette was rooted in Labour politics as a young girl, but it was only in Waikato that politics and activism began to play a strong role in her life. Later, Bill and Olive would turn up to support her at every election. ‘Mum was my greatest supporter and my greatest critic. It wasn’t my politics, but it was my hairstyle, or what I was wearing. She watched everything, even when she was dying. Judith Collins came on the television about two weeks before Mum died, and Mum was coming in and out of delirium and she saw her on the television, and said, “Silly woman.” She remained an ardent Labour supporter to the end. She would not miss the news. She listened to talkback. They never changed. They were of that Michael Joseph Savage generation.’

The other major event in Annette’s life at this time was the end of her marriage to Doug, though they continued to nurture Amanda in their separate ways.

‘It is now public knowledge, of course, that I was married to a transgender person. I didn’t marry one. Doug, whose name is now Petra, declared he was transgender about nine years after we married, and we subsequently separated. For years he continued to live as a man in public, and it is only in more recent years that he came out publicly as transgender. The experience has given me an insight into and understanding of what a difficult life it is for a transgender person. It is probably easier today, but for someone of his era it was unspoken, probably even more unspoken than homosexuality. It was incredibly hard on him, but also incredibly hard on our family. But it has given me empathy for people who are considered different. I had quite a lot to do with Marnie who is a hermaphrodite, and who set up a support group for hermaphrodites. She got me to launch it and then after 10 years we had a celebration for the fact it was still going. I know people don’t choose to be different. It is a hard life to be different. That’s why so many men particularly covered up the fact they were gay. I really like what I see now of acceptance of sexuality and difference. It has changed from the 1980s.

‘My family has stayed friendly with Petra. Before he declared publicly he was transgender, he continued to come to family Christmases. He was coming as a man, of course. But one Christmas Petra had decided to live as a woman, and I said to Ray, my lovely second husband, I need to tell Mum and Dad, because they are a bit older and it will be a bit of a shock when he turns up dressed as a woman. I went down to Picton where they were living by then, and took Mum and Dad for a drive, Mum in the back seat and Dad in the front. I said, you know how Doug was always a little bit different, and they said yes, and then I said, he has decided to live as a woman from now on. There was silence for a while. Then my mother said, he will always be welcome at our house, and my father said, makes no difference to me. And nothing more was ever said. Petra turned up for Christmas, and everyone carried on as if that had always been the case. My elderly parents were in their eighties by then, but when I look back on it, I never heard them judge anyone. I never heard them being bigoted. Maybe they were biased about Labour, but not bigoted. Ray has been very understanding. It certainly wasn’t easy when Doug first told me, but we had a very, very amicable separation.’

Until Annette met Ray Lind in 1999, and took him on a tour of the country to be ‘evaluated’ by her closest friends, her main sources of support and love during her early political years were her family and friends. Ray is the main reason she never sought the Labour leadership at any stage. ‘He was my first chance of real happiness, and I wasn’t going to throw it away by pursuing a leadership role.’

So for 18 years from 1981, Annette’s family became the constant in her life during her first six years in Parliament, the aftermath of defeat in 1990, and the return to Parliament from 1993. Her family was always there. ‘They got to meet the Queen. They met all our prime ministers because I brought them up for occasions. I brought them up for the Queen opening Parliament. Amanda was there too. David Lange introduced all the MPs, and said, this is Annette King, the member for Horowhenua, her parents Olive and Bill Robinson, and her daughter Amanda. He had no paper or notes. Then he moved on to Peter Dunne and said, this is his wife Jenny and family. I watched him go round the room. He had an incredible photographic memory.

‘I was selected to be the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association delegate for Parliament, and I took Mum overseas with me in 1985. We went to the United Kingdom. We went first to Jarrow where Dad’s mining relatives came from. The other side of his family was called Pace. They had been boat builders. So Dad’s name was Frank Pace Robinson. His father was Robert Pace Robinson, and his father was Matthew Pace Robinson. And my grandson William is William Pace Parsons. After the UK, I flew to Canada with Mum for the actual conference and took her all around. She had a great time.’

Annette attributes her huge capacity for work — and love of being involved — to her years in Murchison. ‘It was a family tradition in that era. People worked and you were expected to work. There was a time for working and a time for play, and no excuses not to work and have jobs. I started work for Collins Tearooms in Murchison at the weekends and in school holidays when I was about 12. I earned about a pound a day. I am driven, and I haven’t finished yet. I enjoy work. I get real pleasure out of doing things, being involved, making decisions and seeing results. I love that, just like some people love golf. So since leaving Parliament I have been doing many things, and I am enjoying myself and I haven’t missed Parliament at all.’

Chapter 2

The awakening years

When Annette King entered politics as a candidate in 1984, many New Zealand families still revered Michael Joseph Savage as the symbol and inspiration of the Labour Party. Indeed, Annette talked about the great Labour leader in her first speech at a candidates’ meeting. For her, however, the former leader who had assumed even greater importance was Norm Kirk, the Labour Prime Minister who tragically died in office in 1974. While many family homes proudly hung a photo of the beloved Savage, Annette’s favourite piece of Labour memorabilia is a miniature sculpture of Norman Kirk.

Annette went to her first Labour Party meeting in Hamilton late in 1972, and she was promptly made secretary of the Hillcrest branch. She has been an active member ever since.

‘I joined after Norman Kirk won. I was so impressed with him that I wanted to be part of it. I’d always been a Labour supporter, but I only had my first vote in the 1969 election, because 21 was the age you could vote in those days. I had joined the Labour Party in Motueka, but I became active when Doug and I shifted to Hamilton in 1972, and I went to the Hillcrest meeting. We were running hard against Rob Muldoon after the ’75 election, which Labour lost. We used to highlight the effect his policies were having on people. One of the things we held was a Depression dinner at Waikato University designed to highlight the fact that the wage freeze was coming, the price freeze, the rent freeze, the stalling of the economy and the sinking lid on public servants. At the dinner we fed them potato soup, curried sausages and apple crumble — which sounds quite good today but was considered to be what you’d have if you were in a depression. And we invited our guest speaker, an up-and-coming star in the Labour Party, John Kirk, Big Norm’s son. My job was to pick him up from the airport. He never turned up. He just failed to arrive. The plane came in, no John Kirk. No cellphones, who did you ring to find out where he was? That was my experience of John Kirk.

‘We also formed what we called the Trendy Leftie Club based at the university because Muldoon used to call anyone in the Labour Party a trendy leftie so we decided that we would form the club as part of the Labour Party. We launched it in one of the university buildings. A huge crowd turned up and we invited the up-and-coming lefties of the day — Richard Prebble and Jim Anderton — and the two of them came and launched the club. The whole idea was to highlight Muldoon’s policies and their impact on people and so on.’

The unpopular Vietnam War also had a strong impact on Annette, as it did on thousands of other young New Zealanders. ‘In 1968 my cousin Donald Bensemann was one of the few New Zealanders killed in Vietnam. I was absolutely appalled and shocked at his death. He was a volunteer, he was in the regular army, and I opposed the Vietnam War as others did in Hamilton. We had rallies, all the stuff you did in those days. Not like the stuff they did in Wellington, but in the Labour Party in Hamilton. But Donald’s death had a big impact on me. It brought home the futility of it. And it’s even more futile today. Donald died at 19. Why the hell were we there? I’ve been to Vietnam. What the hell were we doing fighting in somebody else’s country? It was nothing to do with us.’

Annette’s real activism on the street began, however, with the 1974 march of dental nurses on Parliament. ‘Frustration had been building for many years because we hadn’t had a proper pay increase for about 21 years. We had relativity with public health nurses, and the State Services Commission at that stage was trying to prevent us getting a relativity increase. I think it was because we were a bunch of women. They were going to break the relativity. And at the same time we were supposed to be getting new equipment . . . new chairs, these lie-down chairs, but things just weren’t moving. Months were going by. Finally, it came out of Auckland actually. Auckland dental nurses got the PSA involved and they decided to form action committees, and then the action committees started to form branches. We formed an action committee in Hamilton and I was basically the leader of it. Those action committees were fed information by the PSA, which took over the fight for us to retain our relativity. We’d got no movement from the SSC so the PSA decided that we would march. They would fly us into Wellington and we would march on Parliament. That was unheard of then. I think about 16 of us went from Hamilton. We flew down and went back by train. We flew down in full dress uniform on the plane. In Wellington we met at the Town Hall and formed into our regions. We had banners and flags saying where we came from. I was a marshal for the Waikato and had to walk on the outside. I told that story, I think, in my valedictory, marching along and we had one side of the road going to Parliament and cars were allowed to go on the other side, and this car with a very throaty motor, a Zephyr or something like that, went past and this carload of guys yelled out, “Hey, you sheilas.” And none of us looked. We were staring ahead and then they said, “Hey, you Waikato sheilas,” and we swung around and looked, and they said, “Best looking in the bunch.” There was a real spring in our step after that, though nowadays that’s probably considered not PC. We marched all the way from the Town Hall to Parliament.

‘We were divided into groups. Our group met with Dorothy Jelicich and Rufus Rogers. They were the two MPs from Hamilton East and Hamilton West. Maggie Morgan, who became one of my greatest friends though I didn’t know her at the time of the march, and Pam Horncy were in the key group that met with Norm Kirk and Minister of Health Bob Tizard.

‘So we went in in groups and we told them why we should have a pay increase and we should retain our relativity. The truth of the matter I think is that the meat inspectors had been primed by the Auckland delegates. Pam Horncy and others had gone out to meatworks and spoken to meat inspectors, because they were public servants, about how breaking relativity could affect them, because they had relativity with someone else. So the meat inspectors then made it clear that if we didn’t get relativity they would disrupt the freezing works. So I think they had a bigger impact probably than the march.’

After the march experience, Annette continued to be an activist in terms of dental nurse issues. ‘We had a big campaign about handling mercury. It was decided to test us for the level of mercury, because it’s a poison, and for generations we had had to mix mercury and silver alloy fillings by hand to become silver amalgam. You had to squeeze the mercury out of it. And you tipped your mixture into a piece of gauze and you squeezed it by hand into bottles; a lot of it fell on the floor and we’d give it to kids to take home. It was quite fun because you couldn’t really touch quicksilver. Anyway a scientist, Dr Bill Glass, decided they needed to test us for mercury levels in our bodies. And they tested us; it was done by a urine test. I’ve never forgotten it because you had to collect every bit of urine for 24 hours, which normally wouldn’t be a problem except I was the dental nurse at Knighton Normal School, a very social school, and they had a party the night I was to collect it. It was a great party. Lots of wine was drunk and I had to take the bottle with me to the party because I had to collect every drop. At the party I was ducking into the loo filling up, then drinking some more wine. By the time we got to the 24 hours mine was full to the brim. I reckon there was probably more alcohol in it than urine, but anyway I tested fine. They didn’t find high levels of mercury in my urine or inside my body, but they did with some nurses. Some got very high levels and were laid off work for a while and then changes were made in the way mercury was handled. We got machines to actually do the mixing. They’ve still got the same machines these days.’

Annette says her 1974 experiences with the dental nurses had an important influence on her future career. ‘First of all, it gave me courage because I wasn’t always an outspoken woman. Not shy, because I’ve never been shy, not even at school, but I suppose I was brought up that you had to have good manners, and I had a father who was the head of the house, so I was brought up that even though he had three daughters he still ruled the roost. It was a traditional family. The older I got the more feminist, if you like, I became. The more I saw how unfair it was. I knew that women could be just as good as men at these jobs, and that march gave me courage to speak out. I’d never been on a march like that. I’d been to Labour Party rallies, been to Labour Party conferences, but I’d never experienced anything like that.’

The experience may not have led directly to a political career, but she says it gave her the courage to become involved in grassroots Labour politics. Encouraged by Doug, she studied part-time at Waikato University, and she also credits the then Department of Health for helping her broaden her horizons. ‘They allowed me to leave work at 4.30 three days a week so I could be at the university by five for a five o’clock lecture. I wasn’t supposed to finish until quarter to five, but they let me off at 4.30. So the combination of the Labour Party, going to university, where I was now studying politics and history and English, and my activities in the Dental Nurses’ Institute I think was really my awakening in terms of having the courage to get involved in things. It also gave me an insight into how things worked, and I suppose it gave me determination because it hadn’t entered my head that I might be a politician. I’d fought for Rufus Rogers’ re-election in ’75, and I was absolutely shocked and horrified when he lost. We had the election-night party at my place in Hamilton. Of course, you didn’t have polls in those days. I thought we had done really well, and I was just devastated when we lost both Hamilton East and Hamilton West. Then I worked on Lois Welch’s 1978 campaign. We lost again, but everything was building up my political awareness and courage and involvement. It was layer upon layer if you like.’

Annette shifted to Wellington in 1981 to do a post-graduate diploma at the dental school, and she joined the Mt Victoria branch of the Labour Party. ‘Cath Kelly was the president and she got me to be secretary as soon as I arrived. But I also joined up with the dental nurses here and I crucially met Maggie the same year. Maggie and Dave Morgan were to become great friends and also important political influences and supporters. The advanced diploma course was a year long, and I immediately got involved with the dental nurses’ PSA group in Wellington and became the vice-president. That’s when I first met Maggie.

‘Maggie and Dave had an adopted daughter, Jenny, and Amanda used to babysit her. She’s about five years younger than Amanda. I’ll tell you who used to babysit Amanda — Helen Kelly. So I got very friendly with Cath and Pat Kelly. I used to spend several Sundays a month at their place for lunch. Maggie and I just immediately got on. She was out there, far more out there than I was. Outrageous hairdos, outrageous clothes and of course Dave was right at the forefront of the media in those days with his union activity. I spent an awful lot of time at their house as well. And I lived in Evans Bay and they used to come around to my place with Jenny on Sunday afternoons and we’d sit yakking for hours. Maggie was working out at Cannons Creek so she was working really tough areas but was totally committed to improving the lot of dental nurses.’

Maggie Morgan says she was living in Auckland in 1974 and didn’t know Annette at that stage. ‘Most of the organisers were in Auckland even though there were groups right round the country organising. You know we were organising Auckland, which had one of the biggest contingents. I think Annette’s group went home on the railcar, so the Hamilton girls were doing it on the cheap. We had to fly in and out obviously.’

Maggie says the final settlement worked out at about 22 per cent. ‘It was amazing really because we were seeking relativity with public health nurses and that’s what we got. Huge backpay. I can barely remember what I spent it on, but anyway it was very good.

‘Bob Tizard was the Minister of Health and I went to Kirk’s office with our delegation after we’d arrived at Parliament. Kirk asked us questions and Tizard was a bit kind of, you could see he wasn’t pleased with the way the conversation was going, and then Kirk said, well, I can’t actually remember the words, but Pam Horncy was there as well, and he said, “Well, I can’t see why this can’t happen.” It’s not what he said, but you know words to that effect.

‘I didn’t actually meet Annette till the 1980s in Wellington. I imagine I met her first through the Dental Nurses’ Institute, the Wellington branch, because I think I was active in the PSA when I first went down. I was dental nurses’ delegate for quite a while, but I don’t think there was any PSA mechanism where we met. I think we met at the Institute branch stuff, which was kind of like our professional body.

‘I was working at Cannons Creek School in Porirua. But there was a lot of activity that went on post the 1974 march. We had a lot of health and safety stuff going on. Activity just kept going so I was interviewed on radio and TV, and I had a typewriter at the dental clinic doing other things you know other than actually doing teeth. That went on for a long time.

‘I think Annette was probably highly political when I met her, but I just don’t remember that. It’s funny. She might have been. We became good mates. She’d often talk to Dave, and our girls went to school together at St Mark’s and our daughter went home to Annette’s place after school with Amanda. You know we were around there a lot at dinners and lunches and family things with her family. She came and wallpapered our bathroom and tried to break her leg falling off the ladder. That was her and Dave doing that. I don’t remember her being political, but she probably was.’

Maggie believes the relationship was more one that came out of shared interests, family, children and friendship, rather than political agitation. ‘It’s kind of like meeting a soulmate, meeting someone you know is going to be on the spectrum of political thought that you are on . . . because dental nurses are a notoriously conservative bunch.’

Annette says that although her activism as a dental nurse sparked her interest in politics, she didn’t have specific political ambitions when she went to Wellington.

‘I wasn’t thinking of standing for Parliament, but I was asked whether I would stand for local government. It was Fran Wilde who said to me I should stand for the local body elections and that must have been 1983.

‘I was still thinking about that when Bill Rowling an-nounced he was retiring from the Tasman seat. Fran and Helen Clark said, why don’t you put your name in for Tasman, you come from Murchison, it’s in the electorate, why don’t you stand for Parliament? I really hadn’t thought about becoming an MP, but we wanted more women in Parliament in 1984. We’d held a big women’s conference at Waikanae. You had leaders like Ann Hercus, Margaret Shields, Fran and others, they were pushing us, encouraging women to put their names forward. And out of that push you got Anne Collins, Judy Keall and me. They encouraged us to take a risk, so I did.’

Of that first foray into national politics, Annette says she found it really hard selling herself because that was not her natural game.

‘You have to say how good you are, and that’s not how I was brought up. People weren’t meant to be skites. It is probably a gender thing too. Probably men find it easier to talk about their achievements. You know even now I find it quite hard to show off, to say I’ve done all these things. It’s just ingrained in me.’

Chapter 3

Warm glow of victory

Annette King sat by the window in the Prime Minister’s lounge on the ninth floor of the Beehive. Not yet a pivotal figure in the Labour Party, she and fellow newbie MPs Clive Matthewson and Jim Sutton were trying to talk sense into Prime Minister David Lange and Finance Minister Roger Douglas.

It was 1988 and the relationship between the two men had in reality broken down after Lange had unilaterally dumped Douglas’s proposal for a flat tax in January that year. Many Labour MPs had become increasingly alarmed at what the breakdown meant, even if they themselves were bitterly divided over Douglas’s radical economic reforms.

Rogernomics, as Douglas’s economic theory had become known, and the Labour Party itself were at a crossroads with no clear signposts.

While Annette sat by the window overlooking the parlia-mentary grounds, she remembers Lange and Douglas sitting opposite her, side by side. They were side by side, but clearly they were no longer together. The rift had become irreparable.

Five years earlier Annette, while she dreamed of a political career, could not have imagined herself sitting in a room with Lange and Douglas, let alone acting in such an important peacemaker role.

By 1983 the horse-riding, family-loving, happy country girl had become a professional young woman, an accomplished and passionate dental therapist, a degree from Waikato University and her first marriage behind her. Annette was working in Wellington as a dental tutor and living there with her 13-year-old daughter Amanda. She was rapidly becoming politically active, and, in an important step for her future career, she had joined Fran Wilde’s Wellington Central campaign committee in 1981 and developed a strong liking for the future Cabinet minister and Wellington mayor.

The liking and respect were clearly mutual as Fran became an important political ally and influence. In 1983, the last but one of the Muldoon years, Fran encouraged Annette to put her name forward for the Labour nomination in Tasman. Annette surprised herself by accepting the challenge. ‘It certainly wasn’t a plan. I hadn’t even considered standing for Parliament at that stage. I was living in Wellington. I had a young daughter, and I didn’t know how to go about running a campaign. Tasman [former Prime Minister Bill Rowling’s electorate] was a big area and I didn’t even have a car.’

As Annette was to discover throughout the rest of her political career, her friends were often the best source of support. ‘A Blenheim friend, Alex Grooby, lent me his old Peugeot, and I drove it to meetings all over the electorate for the two weeks of the campaign for the nomination.’