21,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

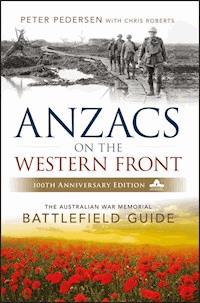

A newly updated, lavishly illustrated account of the ANZACs involvement in the Western Front—complete with walking and driving tours of 28 battlefields.

With rare photographs and documents from the Australian War Memorial archive and extensive travel information, this is the most comprehensive guide to the battlefields of the Western Front on the market. Every chapter covers not just the battles, but the often larger-than-life personalities who took part in them. Following a chronological order from 1916 through 1918, the book leads readers through every major engagement the Australian and New Zealanders fought in and includes tactical considerations and extracts from the personal diaries of soldiers.

Anzacs On The Western Front: The Australian War Memorial Battlefield Guide is the perfect book for anyone who wants to explore the battlefields of the Western Front, either in-person or from the comfort of home. It does far more than show where the lines that generals drew on their maps actually ran on the ground and retrace the footsteps of the men advancing towards them. It is a graphic and wide-ranging record of the Australian and New Zealand achievements, and of the huge sacrifices both nations made, in what is still arguably the most grueling episode in their history.

- A complete guide to the ANZAC battlefields on the Western Front—featuring short essays on important personalities and events, details on relevant cemeteries, museums, memorials and nearby places of interest, and general travel information.

- Carefully researched and illustrated with colorful maps and both modern and period photographs.

- Includes information about the Sir John Monash Centre near Villers-Bretonneux in France—a new interpretative museum set to open on Anzac Day 2018, coinciding with the centenary of the Year of Victory 1918.

Anzacs On The Western Front: The Australian War Memorial Battlefield Guide is the perfect book for historians, history buffs, military enthusiasts, and Australians and New Zealanders who want to explore the military history and battlefields of their heritage.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1094

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

First published 2018 by John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

42 McDougall Street, Milton Qld 4064

Office also in Melbourne

© Australian War Memorial 2018

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act 1968 (for example, a fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review), no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, communicated or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All inquiries should be made to the publisher at the address above. For images and illustrations, refer to sources of illustrations page for appropriate copyright holder.

Cover design by Delia Sala/Wiley

Cover images supplied by the Australian War Memorial: Front cover image — Australian soldiers walking along the duckboard track at Tokio, near Zonnebeke — E01236; gatefold image — Rising Sun badge — REL28780. Poppy field image — © Kochneva Tetyana/Shutterstock.

Disclaimer

The publisher and the author make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation warranties of fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales or promotional materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for every situation. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional services. If professional assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. The fact that an organisation or website is referred to in this work as a citation and/or a potential source of further information does not mean that the author or the publisher endorses the information the organisation or website may provide or recommendations it may make. Further, readers should be aware that internet websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Please be advised that travel information is subject to change at any time. We therefore suggest that readers write or call ahead for confirmation when making travel plans. The author and the publisher cannot be held responsible for the experiences of readers while travelling.

CONTENTS

Foreword

Preface

About the author

Acknowledgements

Note to second edition

Introduction

The ANZACS on the Western Front

CHAPTER 1 1916 Bois-Grenier/Fleurbaix

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 2 1916 Fromelles

Walking the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 3 1916 Somme: Pozières/Mouquet Farm

Driving/walking the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 4 1916 Somme: New Zealanders at Flers

Driving/walking the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 5 1916–17 Somme: Australians at Flers and Gueudecourt

Driving/walking the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 6 1917 Australian Advance, German Counterattack

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 7 1917 Bullecourt

Walking the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 8 1917 Ypres

Walking Ypres

Local information

CHAPTER 9 1917 Messines

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 10 1917 Menin Road

Driving/walking the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 11 1917 Polygon Wood

Driving/walking the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 12 1917 Broodseinde

Driving/walking the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 13 1917 Passchendaele

Walking the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 14 1918 From La Signy Farm to Puisieux

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 15 1918 Dernancourt and Morlancourt

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 16 1918 Villers-Bretonneux

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 17 1918 Hazebrouck

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 18 1918 Hamel

Walking the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 19 1918 The German Army’s black day

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 20 1918 Somme South

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 21 1918 Somme North

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 22 1918 Mont St Quentin and Péronne

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 23 1918 Hindenburg Outpost Line

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 24 1918 Hindenburg Line

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 25 1918 Montbrehain

Walking the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 26 1918 The New Zealanders at Bapaume

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 27 1918 The New Zealand Advance

Driving the battlefield

Local information

CHAPTER 28 1918 The New Zealanders at Le Quesnoy

Driving the battlefield

Local information

Useful information

Glossary

Select bibliography

Sources of illustrations

Index

EULA

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Preface

Pages

ix

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvii

xviii

xix

xx

xxi

xxii

xxiii

xxiv

xxv

xxvi

xxvii

xxviii

xxix

xxx

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

9

10

11

12

13

14

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

116

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

135

136

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

267

268

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

369

371

372

373

374

375

376

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

417

418

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

429

430

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

489

490

491

492

493

494

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

543

544

545

546

547

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

FOREWORD

I welcome this new edition of the Australian War Memorial’s guide to the Anzac battlefields on the old Western Front. It sets out the many interpretive enhancements created on the battlefields to commemorate the centenary of the First World War and the changes inevitably wrought by progress since the first edition appeared in 2011. At the same time, it retains the elements that made the earlier edition so successful.

Fittingly for a publication with ‘Anzac’ in its title, Australians and New Zealanders receive equal attention in this guidebook. Their battles are explored in numerous drives and walks, designed as much for the casual visitor as the military historian and heavily illustrated by easily followed maps, modern and period photographs, and artworks. Though brief essays on key personalities and military developments lend context and all relevant cemeteries and places of interest are described, the emphasis is on what actually took place. The aim is to put you on the scene of the action.

What happens next is up to you. As Dr Peter Pedersen emphatically points out, you should call on your imagination to visualise the scene as it was. It’s not hard. Feeling that I owed it to the men who fought on them, I often let my imagination take over during my many visits to the battlefields as Australia’s Ambassador to Belgium, Luxembourg, the European Union and NATO between 2006 and 2012. The reward was an appreciation of the enormity of what those men endured and achieved. Put your imagination to work and you’ll feel the same way.

The two and a half years that their soldiers spent on the Western Front remains arguably the worst ordeal that Australia and New Zealand have undergone. On the Memorial’s Roll of Honour, the 46,000 Australians who died on the Western Front easily outnumber the dead from all our other wars combined. Most of New Zealand’s 17,000 fallen died on the Western Front too. Yet there is no denying that the war was won there. Australian and New Zealand soldiers played a leading role in that outcome.

If you let it, this new edition of the Memorial’s guidebook will bring the Australian and New Zealand experience on the Western Front alive. You’ll then more easily understand why we emerged from the Western Front having earned the admiration of the world, and with a greater confidence in ourselves and a deeper awareness of what it means to be an Australian or a New Zealander.

Those who contributed to the guidebook — and there were many of you — should be proud of the result. The commitment of the Australian Department of Veterans’ Affairs and our publisher, Wiley, deserve special acknowledgement. They needed no convincing of the need for a new edition and did everything possible to bring it to fruition. The team here at the War Memorial were also tireless in making it happen.

All of you have my thanks. The Australians and New Zealanders who visit the battlefields thank you too.

The Hon Dr Brendan Nelson AO

Director, Australian War Memorial

Canberra, 2017

PREFACE

During the writing of the first edition of this guidebook in 2009/10, the Australian Department of Veterans’ Affairs was planning a trail that would link the sites of the major Australian battlefields on the Western Front. Called the Australian Remembrance Trail (ART), it was to be completed over the First World War centenary period, 2014 to 2018. The first edition could do nothing more than foreshadow its creation. Now the ART is well-established and New Zealand’s Ministry of Culture and Heritage has set up Ngā Tapuwae Western Front, trails that embrace the main New Zealand battlefields. Downloadable apps enhance the interpretation on both the ART and Ngā Tapuwae. An updated edition of the guidebook that includes these enhancements became necessary.

User experience and the changes that have occurred on the battlefields since 2010 reinforced the need. There are now more windmill farms. Houses – and housing estates – have sprung up where there were none before. Tracks have been ploughed over and become part of fields. New roundabouts and one-way streets have altered traffic flows. Copses have been cut down. Tree and vegetation growth have made some reference points harder to spot. The commercial premises that marked some sites have gone. Additional outbuildings have altered the look of some farms. Progress makes such developments inevitable. Continuing research has resulted in new information that requires occasional modification of the old. That’s progress too.

Though it is well and truly reflected in this update, the march of progress has – thankfully – not compelled any significant adjustments to the battlefield drives and walks. Except for some minor changes to Bois Grenier, Fromelles and Villers-Bretonneux, they remain unchanged. True, some things you are looking at might not be as obvious as they once were, but this is easily remedied by heeding the advice given in the first edition and repeated here: PUT YOUR IMAGINATION TO WORK! But you’ll do that anyway. It’s the key to understanding what happened on the battlefields and, therefore, to making a visit to them a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Peter Pedersen

Canberra 2017

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr Peter Pedersen has written ten books on the First World War and contributions to several others, as well as numerous articles on campaigns from both world wars, the Vietnam War, and battlefields and military and aviation museums worldwide. He appears frequently on Australian television and radio and has spoken at military history conferences and seminars in Australia and abroad. He has also guided many tours to the Western Front and other battlefields in Europe and Asia, which included leading and organising the first British tour to Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam. A graduate of the Royal Military College, Duntroon, the Australian Command and Staff College, and the University of New South Wales, he commanded the 5th/7th Battalion (Mechanised), the Royal Australian Regiment, and was a political/strategic analyst in the Australian Office of National Assessments. After joining the Australian War Memorial as Senior Historian, he became Head of its Research Centre and then Acting Assistant Director of the Memorial and Head of the National Collection Branch. On retiring from the Memorial, Dr Pedersen was appointed consultant historian for the Australian government’s commemorative projects on the Australian battlefields of the Western Front.

Other books by Peter Pedersen

Monash as Military Commander

Images of Gallipoli

Hamel

Fromelles

Villers-Bretonneux

The Anzacs. Gallipoli to the Western Front

Anzacs at War

Anzac Treasures. The Gallipoli collection of the Australian War Memorial

Gallipoli (with Major General Julian Thompson and Dr Haluk Oral)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people contributed to this book.

Brigadier Chris Roberts AM, CSC (Retd) stood head and shoulders above all of them. Chris served with the SAS in Vietnam and has always been keenly interested in military history. His book on the ANZAC landing has become the standard work. I know Chris from our army days together and was delighted when he volunteered to help with the project as a researcher. From the outset he was infinitely more than that. He plotted the data gleaned for each battle on the relevant map and then drew up a detailed framework for the drive or walk that was invaluable for me. His comments, as a soldier who has led in battle and also held senior command, on tactics and terrain during our visits to the battlefields were immensely helpful. Chris also undertook the myriad ancillary tasks, some unforeseen, that arose during the project’s course. Mate, without your enthusiastic help, I’d have laboured to get the book done. I dedicate it to you with ‘the deepest of gratitude and respect’.

The staff of the Australian War Memorial took the project to their hearts. Major-General Steve Gower AO, AO (Mil), the Memorial’s Director, gave me every encouragement and support. So did Nola Anderson, Head of National Collections Branch, and Helen Withnell, Head of Public Programs Branch. Marylou Pooley, Head of Communications and Marketing, who had the idea for the project, was a tower of strength throughout. My colleagues in the Research Centre and the Military History Section shouldered extra duties so that I could concentrate on my writing. I must mention Craig Tibbits, Senior Curator of Official and Private Records, in this context. Craig did a superb job while filling in for me as Head of the Research Centre towards the end of the project, which gave me a clear run to the last full stop. Janda Gooding, Head of Photographs, Sound and Film, Hans Reppin, Manager, Multi-Media, and Bob McKendry, Image Interpreter in Multi-Media ensured that the illustrations were of the highest quality possible. Anne Bennie, Head of Retail and Online Sales, handled the considerable administrative dimensions of the project.

The maps reflect Keith Mitchell’s cartographic skill. Less obviously, they also reflect his forbearance and good humour in accommodating the frequent changes needed to get them exactly right.

On the battlefields, Martial Delabarre in Fromelles, Jean Letaille in Bullecourt, Claude and Collette Durand in Hendecourt, Philippe Gorczynski in Cambrai, Charlotte Cardoen-Descamps in Poelcapelle, and Johan Vanderwalle at Polygon Wood were unstinting in their advice, assistance and hospitality. Closer to home, Dolores Ho, Archivist at the Kippenberger Military Archive in the New Zealand Army Museum at Waiouru, and, in Wellington, the staff of both the National Library of New Zealand/Alexander Turnbull Library and Archives New Zealand exemplified the ANZAC bond by handling every request for information promptly and efficiently.

To one and all, a heartfelt thanks.

NOTE TO SECOND EDITION

I would like to thank the many users of the first edition of this guidebook whom I have met on the old Western Front and back in Australia. Your compliments are deeply appreciated and made the work that went into the guidebook worthwhile. They were also the inspiration for this update, which seeks, like its predecessor, to encourage visits to the battlefields and ensure that the experience remains rich.

Major General David Chalmers AO, CSC, First Assistant Secretary, Commemorations and War Graves at the Australian Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Ian Fletcher, the department’s Director of Overseas Projects, and Dr Brendan Nelson AO, Director of the Australian War Memorial, fully realised the need for a new edition of the guidebook and their generous support ensured that I had the means to complete it. In France, Wade Bartlett and Caroline Kempeneer took time off from working on Australian commemorative projects to take me around the battlefields so that I could revalidate each walk and drive. The frequent backtracking and rechecking involved proved that they had inexhaustible reserves of humour and patience. Wade’s astute user comments along the way were especially helpful. He also took many of the new photographs. John Wiley and Sons Australia, publishers of the first edition, leapt at the chance to do the second one. The enthusiasm of Ingrid Bond, Senior Editor, and her team was heart-warming.

Without your help, this second edition would not have seen the light of day. All those who want to know more about these great campaigns and the immortal legacy left by the Australians and New Zealanders who fought in them are in your debt.

INTRODUCTION

Congratulations on buying this guide. You may have done so out of an interest in the Australian and New Zealand role on the Western Front. You may have wanted to follow in the footsteps of a forebear or see where he fell and where he rests. Each of these reasons is an acknowledgement of what Australia and New Zealand did on the Western Front. It was the decisive theatre of the First World War and both nations made their greatest contribution to victory there. Gallipoli was a sideshow, though it helped to establish the Australian and New Zealand national identities and enriched the English language with the word ANZAC. But for Australians and New Zealanders a certain romance attaches to Gallipoli, with its idealised images of bronzed men storming ashore at ANZAC Cove and clinging to cliff-top positions. The Western Front, on the other hand, evokes only images of appalling slaughter for a few acres of mud. It cost Australia and New Zealand more casualties than all of the conflicts they have fought since put together. Not surprisingly, then, the Western Front has always stood in Gallipoli’s shadow. You are helping to bring it out into the sunlight.

Walks and drives

Australians and New Zealanders often forget that the term ‘ANZAC’ refers to both of them and not to just one or the other. As the title of this guide contains the term, the pages that follow lay out detailed instructions on walking or driving the major battlefields on which the Australians AND the New Zealanders fought on the Western Front. The battles are covered more or less in the order in which they occurred from 1916 to 1918. This format allows them to be fitted clearly within the context of the war, which, in turn, makes for an easier understanding of how the war played out, the important tactical milestones passed along the way and how the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) evolved to meet the war’s changing demands.

Unfortunately, the chronological order doesn’t match the geographical one. The AIF and NZEF areas of operation stretched 150 km from the Belgian coast at Nieuport to the Hindenburg Line near St Quentin in France. In 1916 the AIF and NZEF started off in French Flanders in the north before moving south to the Somme River. In 1917 most of their major battles were in the north again, around Ypres in Belgian Flanders. In 1918 they headed back to the Somme and then advanced eastwards. Following the battles in chronological order would necessitate duplication in the geographical order; following the geographical order would reduce the chronological one to incomprehensible nonsense.

By grouping the battlefields into four operational sectors, though, and travelling to and within these sectors in a prescribed sequence, the chronological order can be approximated. The Australian War Memorial successfully used a similar structure in its battlefield tours for many years. Simply start from Ypres in Belgian Flanders in the north, continue south to the Somme and then travel east to the Hindenburg Line. To reach Ypres from Calais, head east from the ferry terminal on the A16-E40 autoroute and then swing onto the N8 as you approach the Belgian town of Veurne. From Paris, head north on the A1/E17 to Lille, pick up the A27/E42 (direction Tournai) and then the A17 and A19. On leaving Ypres, take the N366 and N365 to Armentières, followed by the A1 to Bapaume and then the D929 to Albert or Amiens. You are now on the Somme. The recommended sequence of battlefield walks and drives in each sector is:

Flanders 1916–18:

– Ypres

– Messines

– Menin Road

– Polygon Wood

– Broodseinde

– Passchendaele

– Bois-Grenier/Fleurbaix

– Fromelles

– Hazebrouck

North of the Somme 1916–18:

– Pozières/Mouquet Farm

– Flers (NZ)

– Flers/Gueudecourt

– 1917 Hindenburg Line advance

– Bullecourt

– Hébuterne/Le Signy Farm/Rossignol Wood/Puisieux

– Bapaume (NZ)

– Dernancourt/Morlancourt

South of the Somme 1918:

– Villers-Bretonneux

– Hamel

– Amiens 8 August

– Lihons, Proyart and Chuignes

– Etinehem, Bray, Curlu

– Mont St Quentin/Péronne/ Bouchavesnes

Hindenburg Line 1918:

– Hindenburg Outpost Line

– Hindenburg/Beaurevoir Lines

– Montbrehain

– Trescault Ridge to Beaurevoir Line (NZ)

– Le Quesnoy (NZ)

Of course you can be selective and only visit the battlefields that interest you. There are plenty to choose from!

Each battle has its own chapter. As well as the battlefield walk or drive, the chapter includes information on nearby places of interest, perhaps text boxes on relevant personalities and issues, and, where relevant, the locations of the bas-relief commemorative plaques hand sculpted by Melbourne periodontist Dr Ross J. Bastiaan. These can now be found on virtually every battlefield on which Australians have fought. Local cemeteries pertinent to Australians and New Zealanders are also covered. There is a tendency nowadays in both guidebooks and on battlefield tours to ‘do’ the battlefields by going from cemetery to cemetery. Make no mistake, this guide emphatically puts the fighting that took place then on the ground as it is now. Everything else is secondary.

The length of each walk or drive is given but the time you spend on it is up to you. To do them all thoroughly would take about three weeks. If you have the time and inclination, fine. Few people do. But you can whiz around most of them in half a day; less if you decide to go only to the locations of particular actions. The walks can be partly driven. Whether walking or driving, do not forget that the Australians and New Zealanders fought as part of a British Expeditionary Force (BEF) that also included Canadians and South Africans as well as, predominantly, soldiers from Britain. Large French and, towards the end, American armies fought alongside the BEF.

General advice to travellers

Your first decision is when to go. In making it, consider one factor above all else: the old Western Front is a long way from Australia and New Zealand, so you can’t come back tomorrow to see what you missed out on today. That means doing as much as possible in whatever time you have, which suggests the European summer, June to August, as the optimal time. The weather is at its best, by European standards anyway, and the days are long, so you can pack a lot into them. The trouble is, everyone else thinks like that. The battlefields are crowded — half of Britain seems to be on the Somme in July — and accommodation is at a premium. If the crops haven’t been harvested, forget extensive battlefield panoramas. You avoid most of these problems in spring and autumn, although the weather is sharper then. But winter is a rotten time to be outdoors, particularly for us antipodeans. The days are short and sometimes entirely fog-bound, and the battlefields are muddy and often snow-covered.

Whatever the season, you’ll almost certainly experience the tendency of the weather, even in summer, to cram the four seasons into an hour. So pack a hat, sunglasses, sun cream and a waterproof smock. Most travellers bring a camera but overlook binoculars, without which you won’t be able to appreciate the views from the various vantage points or pick out the more remote locations. A compass will help you orient maps to the ground. You’ll probably have some reference material (like this guide!) as well. By wearing an angler’s or hunter’s vest, with its many pockets, or carrying a small haversack, you can have these things always on hand. It’s very annoying to leave your car to walk to a particular location and find when you get there that you’ve left what you need in the car.

Hat, sunglasses, multi-pocketed angler’s jacket and camera and binoculars on belt: the author, properly kitted out, at Caterpillar Crater, Hill 60.

As the battlefield walks occasionally utilise farm tracks and the adhesive qualities of Western Front mud are legendary, good hiking shoes or boots are a must. While walking, carry plenty to drink, particularly in summer, and something to munch on. To make the best use of your time, get the necessary victuals in the nearest town and have a picnic lunch. In an ironic contrast to the war years, there are many idyllic spots on the battlefields today where you can do so — the banks of the Somme and the Ancre immediately spring to mind.

The battlefields are in rural areas and you really do need a car to get about on them, just as you would in rural Australia or New Zealand. Hiring a bike is an option in some places, particularly Ypres, where the battlefields are flat and compact, but you’ll still require a car to get from one battlefield to another. A car is also the quickest way of seeing the battlefields. Whatever means of locomotion you use, remember that the locals generally make their living from the soil. They get understandably angry when unthinking hikers tramp across their fields and unthinking drivers block their tractors on the narrow roads. Stick to the farm tracks and the edges of the fields and, if in doubt, ask. The goodwill on which all battlefield tourists depend rests on these simple courtesies.

Totem for location on Australian Dernancourt walking trail.

Two points relate specifically to cars: in the vast majority of stops on the drives there is plenty of room for parking, but on occasion you will have to pull over onto the verge. Be careful when you do so. Secondly, the huge growth in tourism to the Western Front has naturally resulted in a huge increase in the number of cars, hired or otherwise, driven by battlefield tourists. They represent rich pickings for those with a malevolent bent. The upshot is a surge in car break-ins. Do not have your trip ruined by leaving valuables on view and becoming a victim. Lock them out of sight in the boot. As you would anywhere else in the world, carry important items on you. That angler’s vest really does come in useful.

One positive result of the rise in battlefield tourism has been the commensurate growth in battlefield accommodation. Quite a few bed and breakfasts have started up on the main battlefields, such as the Somme and Ypres. Some are run by British (and New Zealand) expatriates and English is spoken in most of them. They’ll generally do a packed lunch but don’t serve dinner. The towns relevant to the ANZAC battlefields — Albert, Ypres, Péronne, Armentières and Cambrai — offer a range of accommodation, as well as restaurants that will take care of your dinner needs. The main cities, Amiens and Lille, offer a broader range of both but are less conveniently located. Take the busy city traffic into account and you’ll easily find yourself spending well over an hour a day getting to and from the battlefields, which amounts to the best part of a day out of a week’s stay. Details of local tourist offices, from which advice on accommodation can be obtained, and some handy websites are in the ‘Useful information’ section at the end of the guide.

Information panel for New Zealand Ngā Tapuwae Somme 1916 drive.

Anyone who has been a soldier will recall the warning about unexploded ammunition given before entering a live fire training area. ‘Ammunition is designed to kill’, it went. ‘If you come across any, leave it alone.’ The battlefields weren’t training areas. Millions of shells, including gas shells, were fired on them, not counting those the Germans sent the other way. A good percentage were duds. Farmers turn up about 90 tonnes’ worth every year while ploughing. As the ravages of time may well have rendered this ammunition extremely sensitive and, therefore, still extremely capable of fulfilling its original purpose of killing and maiming, the warning is very relevant today. If you see shells stacked by the road awaiting disposal by the military authorities, or the odd shell or grenade lying about in fields or woods, DO NOT TOUCH THEM. Otherwise you risk becoming the last ANZAC casualty of the Western Front.

The last item on this checklist of dos and don’ts concerns a positive development. Most of the main Australian and New Zealand battlefields now have some form of interpretation on them, ranging from a visitor centre or museum to a simple walk or an information panel. Installed as part of national programs to commemorate the centenary of the First World War, they are supported by online sites and downloadable apps, details of which are in the ‘Useful information’ section. DO take advantage of them. They will enrich your visitor experience.

Maps

You can complete the battlefield walks and drives using the maps in the guide. The Institut Geographique Nationale Blue Series 1:25 000 maps listed at the start of each walk or drive will enable you to orient yourself in relation to locations outside the battlefield area and navigate to cemeteries and places of interest that are also outside it. The IGN 1:250 000 Nord, Pas-de-Calais, Picardie R01 is useful for navigating from an arrival location, such as Calais or Paris, to the battlefields, and for navigating between battlefield areas that are some distance apart. These maps can be obtained from good bookshops in France, Belgium and the UK and in Maison de la Press shops or major supermarkets in France. You can also order them online from IGN at www.ign.fr.

A few words of caution. French road numbers have a life of their own. Indeed, they seemed to mutate in between the research trips done for this guide. Numbered roads aren’t necessarily continuous either. They can end at one place and start up again somewhere else, yet still have the same number. A road might also have several names along its course. This guide reflects the state of play as regards roads at the time of writing. It may well have changed when you get to the Western Front. As you’re now prepared for the eventuality, don’t have a sense of humour failure if it turns out to be the case. Armed with the maps herein, the IGN maps and the initiative for which Australians and New Zealanders are famous — and which our soldiers here had in heaps — you’ll still be able to get around comfortably.

How to use this book

Before starting a battlefield walk or drive, READ THE BATTLE NARRATIVE. It places the battle within the wider strategic and operational setting, outlines the planning factors and also helps you to overcome a very real practical limitation. The directions that the available roads and tracks take often preclude following the battle as it actually unfolded. You may be able to retrace an advance from start to finish on one flank, for example, but have to go from finish to start on the other flank.

On big battlefields, such as the Hindenburg Line advance in April 1917 or the Amiens offensive on 8 August 1918, many key locations cannot be seen from one another. The battle narrative brings coherence and order to the battle, enabling you to visualise where the principal locations were in relation to each other and to set the local actions described along the route within the context of what was happening elsewhere. As you read, try to see the battlefield in your mind’s eye, which will give you a head start when you set foot upon it.

The walks are more detailed than the drives. You can stop anywhere, and more frequently, on a walk than on a drive, which allows the action to be covered in greater depth. It is appropriate then, that Fromelles, Pozières, Mouquet Farm, Bullecourt and Passchendaele, perhaps the toughest battles fought by the Australians or New Zealanders on the Western Front, are covered in walks. But the itineraries for the drives and walks have one thing in common: they explain not only WHAT happened during the battle but also HOW it happened on the ground. This entails describing where the opposing lines ran and the objectives for an attack lay, the direction that the advance took and from whence the counterattack came, the location of German machine-guns, and what the ground itself offered to the Australians and New Zealanders on the one hand and to the Germans on the other. Considerations such as fields of fire, observation and keeping direction are constantly mentioned. Taken together, all of these things go a long way towards explaining why a fight turned out the way it did. Think about them and make up your own mind.

Leave well alone. A dud near the A29 autoroute at Villers-Bretonneux.

There is nothing arcane about any of this. On reaching a location, you will be asked to position yourself in relation to an obvious reference point, such as a road, railway or wood, which gets you facing a certain direction. To follow the action in that location, just look to your front, right or left, or your right front and left front, the directions in between, as directed. Throughout the guide you will see the names of places, features and landmarks in bold font. Some of these bold names appear on the maps; others are in the text and denote locations of interest. At the back of the guide you will find a glossary of the military terms used throughout.

In the end, it has been said, every battle comes down to the infantryman’s willingness to go forward. The walks and drives will bring you closer to him, to his problems, to his fears. But you will be doing them in daylight, whereas much of the fighting took place in darkness made more impenetrable by smoke and mist. So pay particular attention to the soldiers’ descriptions. The apprehension on moving up to the start line, the deafening noise and bone-jarring concussion of the barrage, the frenzy of infantry combat with bayonet and bomb, the gruesome spectacle of tanks crushing machine-gunners, the overwhelming sadness at the loss of a comrade held dear and the juxtaposition of humanity with brutality — the soldiers spare nothing. But this guide cannot fully bring their words alive. You have to breathe life into them by putting your imagination to work. You will then gain some understanding of what it must have been like to be there and also appreciate the battlefields as places where ordinary men achieved great things. The guide will then have fulfilled its aim.

Using ground. How a German machine-gun was sited to catch the 51st Battalion in enfilade as it advanced across the Cachy Switch at Villers-Bretonneux.

A note on place names

This guide uses wartime spellings for the towns and villages mentioned in it. In the case of Belgian Flanders, these were invariably French spellings. Since the war, though, the Flemish spellings have been adopted. Look out for the following changes:

Wartime (French)

Modern (Flemish)

Menin

Menen

Messines

Mesen

Nieuport

Nieuwpoort

Passchendaele

Passendale

Poperinghe

Poperinge

St Yves

St Yvon

Warneton

Waasten

Ypres

Ieper

THE ANZACS ON THE WESTERN FRONT

After their withdrawal to Egypt at the end of the Gallipoli campaign in December 1915, the AIF and NZEF were greatly expanded. Largely by splitting veteran battalions and using the huge pool of reinforcements in Egypt to bring the resulting half battalions up to strength, the number of Australian divisions went from two to four. Another division was raised in Australia and sailed directly to England. There were now five Australian infantry divisions. A brigade formed from reinforcements and another that had arrived from New Zealand joined the New Zealand Infantry Brigade in a separate New Zealand Division. The New Zealand and Australian Division, in which the New Zealanders had served with the 4th Australian Brigade on Gallipoli, was disbanded.

I and II ANZAC

The AIF and NZEF had made up a single corps on Gallipoli, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, known, like those who belonged to it, as the ANZAC. The extra formations necessitated the creation of another corps. I ANZAC, comprising the 1st and 2nd Australian Divisions, and the New Zealand Division, was commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir William Birdwood, who had led the original ANZAC. The 4th and 5th Australian Divisions made up II ANZAC, which Lieutenant-General Alexander Godley commanded. These arrangements were not ironclad. The 4th and 5th Divisions mostly served alongside the 1st and 2nd in I ANZAC, which left Egypt for France in March 1916. II ANZAC followed in June and the New Zealand Division transferred to it soon after. The 3rd Australian Division joined II ANZAC on reaching the Western Front from England in November.

Whereas the isolation of its enclave on Gallipoli had made the ANZAC essentially an independent force, on the Western Front I and II ANZAC constituted a fraction of a BEF that was already 50 divisions strong. The decisions of British commanders affected them much more directly. Those commanders faced the problem that the combination of trench, machine-gun and barbed wire had decisively tilted the balance in warfare in favour of the defence over the attack. Although the same problem had existed on Gallipoli, an open flank offered a way around the defence, but the ANZAC’s attempt to take advantage of it in August 1915 failed. On the Western Front there was no way around. The trenches stretched from the North Sea to the Swiss border and the Germans defending them were highly skilled. They could only be attacked frontally, in other words, into the teeth of the defence.

Brigadier-General Brudenell White.

Somme

Service in colonial wars, which all the British commanders and some Australian ones had, was no help in these conditions. They had to be mastered virtually from scratch. The process was costly. When the 5th Australian Division attacked at Fromelles, in French Flanders, in July 1916, the British plan was poor and the Australian commander lost control of the battle. The 5th Division was destroyed in one night. Faulty planning, some of it Australian, cost the 1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions dearly in attacks on the Somme at Pozières and Mouquet Farm between July and September. Even when an attack succeeded, the crushing retaliatory German bombardments still caused grievous loss. Modern military technology had transformed warfare into ‘mechanical slaughter’, one Australian said. The 28 000 Australian casualties from the Somme and Fromelles amounted to the equivalent of over half of the 48 Australian battalions in France. But the possibility of obtaining the needed replacements through conscription disappeared when a proposal to bring it in was defeated in a divisive referendum in Australia in October 1916. Though the AIF would remain the war’s only volunteer army, manpower shortages dogged it from now on.

Lieutenant-General Sir William Riddell Birdwood

Commander ANZAC 1915, I ANZAC 1916–November 1917, Australian Corps November 1917–May 1918 and the Fifth Army from then until war’s end

Birdwood had an imperial pedigree that matched his mandatory imperial moustache. The grandson of a general and the son of the under-secretary to the government of Bombay, he was born in India, educated in England and had served abroad since 1885, mainly in Indian frontier campaigns until going to South Africa as Kitchener’s military secretary. A teetotaller with an occasional stammer, he had the ambitious man’s flair for self-promotion. But Birdwood also took men for what they were rather than what their appearance suggested. He had commanded a brigade though not a division, and was secretary to the Army Department, government of India, and on the Viceroy’s Legislative Council before being appointed to command the ANZAC. He also commanded the AIF.

Birdwood’s indifference to danger and informal manner won him many friends among the ANZACs, whose affection he reciprocated. But he was no tactician and often failed to grasp the big picture. On both Gallipoli and the Western Front, he depended heavily on his Australian chief-of-staff, Brigadier-General Brudenell White. Courteous, restrained, cerebral, White had planned the withdrawal from ANZAC, which went off without a hitch. Birdwood told him to make sure all the signal wire was reeled up. White was flabbergasted: ‘Heavens! What does he think we are doing here — why I would gladly have left all the guns behind if we could only get the men off safely.’ This episode highlighted Birdwood’s limitations. Not for nothing did he take White with him on leaving the Australian Corps to command the Fifth Army in May 1918. Looking back, White could not recall Birdwood ever having drafted a plan, and as for his much-vaunted visits to the trenches, ‘he never brought back with him a reliable memory of what he had seen’. Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash, who replaced Birdwood as commander of the Australian Corps, had the vision, intellect and tactical grasp that Birdwood lacked.

After the war, Birdwood returned to the Indian Army and became its commander-in-chief in 1925. He lobbied, unsuccessfully, to become Governor-General of Australia. Knighted in 1914 (KCMG) and 1917 (KCB), Birdwood was appointed GCMG, created a baronet and granted £10 000 in 1919. He became a field marshal in 1925.

Lieutenant-General Sir Alexander John Godley

Commander New Zealand and Australian Division 1915, II ANZAC 1916-November 1917, XXII Corps 1918

An ambitious but impecunious mounted infantry officer who preferred the Boer War to Staff College, the 191-centimetre-tall British-born Godley had been appointed by Kitchener to command the New Zealand Defence Forces before the war. He showed his considerable organizational skills by revamping the territorial forces and in the raising of the NZEF, which he commanded. But Godley was highly unpopular among the New Zealanders owing to his aloof manner, short temper, sharp tongue and forceful wife, Louisa. ‘Make ’em run, Alex’, which she allegedly said while Godley reviewed some New Zealanders on parade, became his nickname.

ANZAC, where Godley led the New Zealand and Australian Division, quickly showed his feebleness as a field commander. He lost control of the all-important offensive to outflank the Turks in August 1915. Commanding II ANZAC on the Western Front, he was carried by his two outstanding divisional commanders, General Monash of the 3rd Australian Division, and the New Zealand Division’s General Russell. When II ANZAC was disbanded at the end of 1917, he took over XXII Corps.

Knighted (KCB and KCMG) during the war, Godley was promoted to general in 1923 while commanding the British Army of the Rhine. He served as governor and commander-in-chief of Gibraltar from 1928 to 1932.

Tanks made their debut when the New Zealand Division attacked on the Somme in September but they held more promise than substance at this early stage in their development. The New Zealanders also moved behind a ‘creeping’ barrage, a curtain of shells that lifted steadily ahead of the infantry advance, suppressing the defences as it went. This really was an important tactical innovation and it remained standard for the rest of the war. Though the New Zealanders did not experience fighting of the same intensity as the Australians, their losses were comparable because they stayed in the line for twice as long as any of the Australian divisions. But New Zealand had introduced conscription in August 1916, enabling the losses to be made up with reasonable certainty. Indeed for much of 1917, the New Zealand Division had a fourth brigade, making it the largest division in the BEF.

The Australian Prime Minister, William Morris Hughes, urges a vote in favour of conscription while on the stump in Sydney’s Martin Place during the 1916 referendum campaign. Voters weren’t convinced. He failed to convince them in 1917, too.

After several weeks’ rest, the Australian divisions returned to the Somme towards the end of 1916. As the autumn rains had turned the battlefield into a swamp, their attacks got nowhere. It was also evident that their fighting efficiency had gone backwards as there had not been enough time to properly train the replacements for the losses from the first stint. Though its severity strained morale, winter brought a respite that allowed some of the deficiencies to be fixed.

Bullecourt

When the Germans withdrew to the Hindenburg Line in February 1917 to shorten their line overall and thereby save manpower, the Australians followed up skilfully. The switch from trench warfare to open warfare was as welcomed as it was easily made but it did not last long. Trench warfare returned with I ANZAC’s attacks on the Hindenburg Line at Bullecourt in April and May in support of a British offensive at Arras. Results were mixed.

The artillery had little chance to shred the wire before the 4th Australian Division’s attack in April. At British insistence, a dozen tanks attempted to crush the wire instead even though the Australians had never worked with tanks, while Australian lapses precluded effective artillery support for the infantry. The 4th Division was shattered for no gain. Better preparation enabled the 2nd Australian Division to take part of the Hindenburg Line in May but the fight was gruelling and also drew in the 1st and 5th Divisions. I ANZAC was then thoroughly rested. Recognising that the term ‘Digger’, by which British troops had praised the New Zealand pioneers and engineers for their entrenching exploits on the Somme, richly met their own conception of their job, the Australians now commandeered it.

Flanders

On 7 June II ANZAC participated in the British attack on the Messines Ridge. It was the first time that the Australians and New Zealanders had fought together in a big battle on the Western Front. Messines was a watershed for the BEF too. It now enjoyed artillery superiority over the Germans, which permitted a massive preliminary bombardment and a creeping barrage of great density and depth. The infantry’s advance was to stop well before resistance hardened. In order to keep German counterattacks at bay, a heavy standing barrage would surround the objectives while they were being consolidated. The new scientific techniques of flash-spotting and sound-ranging located German guns so that they could be knocked out beforehand. No detail was overlooked in the preparation. Numerous rehearsals were carried out on ground almost identical to that in the attack sector. Preceded by 19 mines blown under the German line, the attack yielded a great British victory.

Diggers. In what has become perhaps the iconic image of Australian soldiers in the First World War, Lieutenant Rupert Downes addresses his platoon during the great battle before Amiens on 8 August 1918. As a result of the AIF’s chronic manpower shortage by then, the platoon consists of 17 men, about half its normal strength.

Using the same methods, except for the mines, during the subsequent Third Ypres offensive, I and II ANZAC spearheaded the assaults at Menin Road and Polygon Wood, and at Broodseinde, where they attacked alongside each other for the first time. Continuous heavy rain had earlier rendered the battlefield a muddy wilderness. But good weather blessed the ANZAC attacks and they succeeded. Only the final one, by II ANZAC against Passchendaele, failed. Though the rains had returned, again reducing the battlefield to an impassable quagmire, the British high command, and General Godley in II ANZAC, insisted on the attack going ahead. The Ypres campaign cost the Australians 38 000 men and led to a second conscription referendum in Australia. Even more bitter than the first, it was similarly defeated.

The Australian Corps

Yet this cloud did have a silver lining. Ever since the Australian divisions had arrived on the Western Front, the Australian government had wanted them to be together. But the British high command thought that a corps of five divisions would be too large for one man to handle and the system of reliefs within it too complex. A corps of four divisions avoided the problem because two could be in the line with the other two ready to relieve them. When the manpower crisis intervened, Birdwood suggested that the 4th Division, which was the most battle-worn, should temporarily become a depot division to supply reinforcements for the others. Besides averting the 4th’s break-up, the proposal meant a corps of the magical four divisions.

The British agreed and the Australian Corps came into being under Birdwood on 1 November 1917. Following a brilliant German counterattack at Cambrai at the end of November, the 4th Division was best positioned to go into close reserve at Péronne in case the Germans went further. Its brief stint as a depot division was over.

The creation of the Australian Corps came as a total surprise and was greeted with joy. Grouping the Australian divisions in a single formation took full advantage of one of the AIF’s major strengths, its homogeneity. When Australian divisions attacked alongside each other for the first time on the Menin Road, one commander estimated that the effectiveness of his formation had been increased by a third. As casualties and sickness in the Australian Corps were minimal during a mild winter, the steady flow of returning wounded briefly eased its manpower shortage. Having disbanded the 4th Brigade as a result of its losses at Ypres, the New Zealand Division now belonged to XXII Corps, as II ANZAC became.

Stemming the tide

Utilising divisions freed by Russia’s collapse, the Germans unleashed a colossal offensive in March 1918 in a bid to win the war before America’s involvement put victory beyond reach. The Australians and New Zealanders missed the start of the offensive and it was already faltering when the 4th Australian Brigade temporarily joined the New Zealand Division in the British IV Corps at Hébuterne, north of the Somme. Fighting astride the Somme on the BEF’s right flank, the other Australian formations played the main role in shielding the vital communications centre of Amiens. Their crowning achievement was the recapture of the town of Villers-Bretonneux in a difficult night attack on 24 April. When the Germans attacked in Flanders in April, the 1st Australian Division was rushed north to defend Hazebrouck, another important communications hub. Its stubborn resistance ensured the town’s retention.

New Zealanders lunching in the front line at Le Signy Farm, near Hébuterne, where they were heavily engaged during the German offensive in March and April 1918.

Advancing to victory

At the end of May, the final ‘Australianisation’ of the Australian Corps occurred when Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash replaced Birdwood as its commander. Monash was Australian. His divisional commanders were now either Australian or had lived in Australia for many years. These changes coincided with the ebbing of the German tide. The British, French and American counteroffensives that ended in Germany’s defeat could now begin. In July 1918 the Australians launched an attack that effortlessly captured the village of Le Hamel. Combining infantry, artillery, tanks and aircraft, and utilising surprise, Monash’s plan became the blueprint for the much bigger British thrust before Amiens on 8 August, in which the Australians and Canadians swept all before them. This was the first battle in which all five Australian divisions operated together. The Australian Corps broke through the German bastions at Mont St Quentin and Péronne on the Somme at the start of September in one of the Western Front’s rare manoeuvre battles. It went into action for the last time at the end of the month in the successful assault on the Hindenburg Line.

Along with the Canadians, the Australian Corps had spearheaded the BEF’s advance to victory in the war’s final months. At a cost of 23 243 casualties, just over a quarter of whom were killed, it took 29 144 prisoners, 338 guns and countless machine-guns as well as liberating 116 towns and villages. These figures represented about 22 per cent of the captures of the entire BEF, of which the Australian Corps comprised just over 8 per cent, in this period. Through this achievement, Australia had influenced the destiny of the world for the first time in the nation’s history and arguably more than at any time since. For its part, the New Zealand Division took Bapaume in August 1918, conducted a brilliant advance to the Hindenburg Line from the Trescault Spur and then stormed Le Quesnoy just before the Armistice. As the New Zealanders comprised just a single formation in one of many British corps, their feats were, unjustly, overshadowed by what the Australians did. They lost over 4000 men.

Advancing to victory: the ground captured by the Australian Corps and the New Zealand Division.

Reflections

Nowadays historians are fond of pointing out that technical and tactical innovation and material superiority, particularly with regard to artillery, and the German decline gave any British division a good chance of battlefield success as 1918 went on. This is quite true but it does not devalue the accomplishments of the Australians and New Zealanders a jot. Judgements on how good they were are perhaps best left to the soldiers who fought on the two-way rifle ranges with and against them, rather than to historians writing from the comfort of their studies a century afterwards.

Captain Hubert Essame, who had fought on the Somme in 1916, been wounded alongside the Australians at Villers-Bretonneux and who rose to become a general in the British Army, thought the Australian soldier in 1918 ‘the best infantryman of the war and perhaps of all time’. Some had reached that conclusion months beforehand. After Polygon Wood a British general told the 5th Division: ‘You men have done very well here.’ ‘Only as well as ability and opportunity allow’, a Digger shot back. ‘Very well put young man’, the general retorted, ‘but you have undoubtedly the best troops in the world’. The normally reserved British Official Historian, Brigadier-General Sir James Edmonds, remarked: ‘Nothing too good’ could be said of the Australians of 1918. They were ‘the finest’. In 1919 Marshal Foch, who had been Allied generalissimo the previous year, declared the Australian ‘the