28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

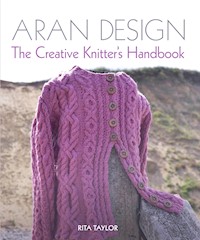

Aran knitwear is instantly recognisable, respectfully fashionable and generously comfortable. With a long-treasured heritage steeped in Irish history, it is no surprise that most knitters express a wish to produce an Aran knit at some time in their creative life. This book delves into the history and heritage of this popular style, offering traditional designs and patterns, whilst providing inspiration for contemporary and innovative adaptations. Written for the dedicated knitter, Aran Design: The Creative Knitter's Handbook offers a unique insight into the trends and techniques associated with the style. This beautifully illustrated book includes: the history of Aran knitting; recommended materials and equipment; a dictionary of stitches; how to plan an initial design; working out the numbers for a project and finishing tips and techniques. It is invaluable reading for all who wish to learn more about Aran knitting.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

ARAN DESIGN

The Creative Knitter’s Handbook

RITA TAYLOR

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

© Rita Taylor 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 408 7

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

Introduction

1History

2Materials and Equipments

3Stitch Dictionary

4Starting a Project

5Aran Knitting Patterns

6Tips and Techniques

Bibliography

Appendix

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Elly Doyle for checking the patterns, to Hilary Grundy for knitting many of the swatches, to photographers Natalie Bullock, Helen James, Marj Law, Rosemary Brown, Ron Wiebe, and to the models, Natalie, Erin and Tess. Thank you to the Knitting & Crochet Guild for permission to use photographs of some of the Aran knitwear in their collection, to the Board of Trinity College Dublin for the picture of the Aran men in their ganseys, and to Batsford Books for the image of the sweater from Gladys Thompson’s book. Special thanks to my husband who has been helpful and supportive throughout this work.

Thank you to Mavis Clark for her memories of her grandmother’s knitting and, last but not least, thank you to the skilful ladies of the Aran Islands who created such beautiful stitches. Without their originality this book would never have come into being.

ABBREVIATIONS

Abbreviations in Patterns

alt

alternate

approx

approximately

beg

begin(ing)

c3f

slip 2 stitches onto a cable needle and hold in front, k1, k2 from cable needle

cm

centimetres

cont

continue

dec

decrease

foll

following

g

grams

inc

increase

incto5

(k1, p1, k1, p1, k1) into the same stitch to make 5 stitches from 1

k

knit

k2tog

knit 2 together

kfb

knit into front and back of same stitch

m1

make 1 stitch by knitting into the horizontal bar between stitches

M1L

make 1 stitch in the left leg of the stitch below

M1R

make 1 stitch in the right leg of the stitch below

m

metres

mb

make bobble: k1, yo, k1, yo, k1 all into the next stitch. Turn, purl these 5 stitches, turn and knit them, turn and purl them again, then, with the right side facing, decrease back to one stitch (other ways of making bobbles are given in Chapter 6)

mm

millimetres

p

purl

p2tog

purl 2 together

p3tog

purl 3 together

patt

(work in pattern)

pfbf

purl into front, back and front of stitch

rem

remaining

rep

repeat

rev st st

reverse stocking stitch

RS

right side

sl

slip

sk2p

slip 1, knit 2 together and pass slipped stitch over the knitted stitches

ssk

slip each of the next 2 stitches independently, return them to the left needle and knit together through back loop

st st

stocking stitch

st(s)

stitch(es)

tbl

through back loops

tog

together

tw2l

Insert the right needle behind the first stitch on the left needle into the back of the 2nd stitch and knit it without dropping the stitches off the needle. Knit into the front of the first stitch and drop both stitches off the needle

tw2r

twist 2 right: knit into the back of the 2nd stitch on the left needle, take the right needle in front of the 1st stitch, then knit into the back of the 1st stitch on the left needle before slipping both stitches off the needle

WS

wrong side

yo

yarn over needle

Abbreviations in Charts

1/1LC

slip next stitch onto cable needle and place at back, k1, then k1 from cable needle

1/1RC

slip next stitch onto cable needle and place at front, k1, then k1 from cable needle

1.1/LPC

slip next stitch onto cable needle and place at back, k1, then p1 from cable needle

1/1LPT

slip next stitch onto cable needle and place at back, k1tbl, then p1 from cable needle

1/1RPC

slip next stitch onto cable needle and place at front, p1, then k1 from cable needle

1/2RPC

slip next 2 stitches onto cable needle and place at back of work, k1, then p2 from cable needle

1/2LPC

slip next stitch onto cable needle and place at front of work, p2, then k1 from cable needle

1/2RC

slip next stitch onto cable needle and place at front of work, p2, then k1 from cable needle

1/2LC

slip next stitch onto cable needle and place at front of work, k2, then k1 from cable needle

1/3LC

slip next 3 stitches onto cable needle and place at back, k1, then k3 from cable needle

1/3RC

slip next stitch onto cable needle and place at front, k3, then k1 from cable needle

1/3RPC

slip next 3 stitches onto cable needle and place at back of work, k1, then p3 from cable needle

1/3LPC

slip next 3 stitches onto cable needle and place at back of work, k1, then p3 from cable needle

2/1RC

slip next stitch onto cable needle and place at back of work, k2, then k1 from cable needle

2/1LC

slip next 2 stitches onto cable needle and place at front of work, k1, then k2 from cable needle

2/1LPC

slip next 2 stitches onto cable needle and place at back, k1, then p2 from cable needle

2/1RPC

slip next 2 stitches onto cable needle and place at front, p1, then k2 from cable needle

2/1/2RPC

slip next 3 stitches onto cable needle and place at back of work, k2, slip left-most stitch from cable needle to left needle, move cable needle with remaining stitches to front of work, p1 from left needle, then k2 from cable needle

2/2LC

slip next 2 stitches onto cable needle and place at back, k2, then k2 from cable needle

2/2RC

slip next 2 stitches onto cable needle and place at front, k2, then k2 from cable needle

2/2LPC

slip next 2 stitches onto cable needle and place at front, p2, then k2 from cable needle

2/2RPC

slip next 2 stitches onto cable needle and place at back, k2, then p2 from cable needle

2/3LPC

slip next 2 stitches onto cable needle and place at front, k3, then p2 from cable needle

3/1LC

slip next 3 stitches onto cable needle and place at front of work, k1, then k3 from cable needle

3/1RC

slip next stitch onto cable needle and place at back of work, k3, then k1 from cable needle

3/1LPC

slip next 3 stitches onto cable needle and place at front, p1, then k3 from cable needle

3/1RPC

slip next 3 stitches onto cable needle and place at back, k3, then p1 from cable needle

3/2RPC

slip next 2 stitches onto cable needle and place at back of work, k3, then p2 from cable needle

3/2LPC

slip next 3 stitches onto cable needle and place at front of work, p2, then k3 from cable needle.

3/3LC

slip next 3 stitches onto cable needle and place at front, k3, then p3 from cable needle

3/3RC

slip next 3 stitches onto cable needle and place at back, k3, then p3 from cable needle

4/1LPC

slip next 4 stitches onto cable needle and place at front, k1, then p4 from cable needle

4/1RPC

slip next 4 stitches onto cable needle and place at back, p1, then k4 from cable needle

4/2RPC

slip next 4 stitches onto cable needle and place at back of work, p2, then k4 from cable needle

4/2LPC

slip next 4 stitches onto cable needle and place at front of work, p2, then k4 from cable needle

4/4LC

slip next 4 stitches onto cable needle and place at front, k4, then k4 from cable needle

4/4RC

slip next 4 stitches onto cable needle and place at back, k4, then k4 from cable needle

6/6RC

slip next 6 stitches onto cable needle and place at back of work, k6, then k6 from cable needle.

6/6LC

slip next 6 stitches onto cable needle and place at front of work, k6, then k6 from cable needle.

INTRODUCTION

There are many opinions on what are the origins of Aran knitting, but the truth is that it is a reasonably young tradition. However, a tradition it is, and people do have an idea of what constitutes a typical Aran sweater. It has a comfortable fit, is usually made from a fairly thick, undyed cream wool and features vertical patterns of crossing stitches, some of which look like ropes, some diamond shapes and some criss-crossed like ribbons. Traditionally there is a wide central panel flanked by bands of cables (the rope-like patterns). Some garments are decorated with bobbles. It is a unisex garment and can be made as a sweater or cardigan in all sizes to fit babies to adults.

Of late some of the central panels have become very intricate, inspired by the Celtic and Viking designs found on stones and crosses. The originators of these motifs appear to be Elsebeth Lavold in her Viking knitting books and Alice Starmore in Fishermen’s Sweaters. There are also a number of inventive knitters who have created new cables through experimentation. While these are not ‘traditional’ Aran motifs, they look pleasing and beautiful and are another option for the designing of Arans, so I have included one or two here. These intertwining patterns now appear to be accepted as traditional elements in Aran design. While some may disagree about their authenticity, I see no problem with it. Artists of all kinds like to push the boundaries of their crafts, continuing to experiment in order to keep the craft alive.

An curragh from the Collection of the Knitting and Crochet Guild.

What this book aims to do is help you to design an Aran sweater yourself; to become comfortable with working a variety of cable stitches and to understand how they work. The more that you experiment, the more you will discover the potential for ‘inventing’ new cables. This book is not so much an instruction manual, but more a guidebook to help you develop your own ideas. While there are already many existing patterns that you can follow to the letter, my aim is to get you to follow the example of the knitters of the Aran Islands and see how satisfying it is to create something that you have planned and designed for yourself.

While the book does contain a few patterns for you to work as they are, it also gives ideas for ways to change these patterns into a different design, either by changing the shape or inserting different cable motifs. It does not contain basic knitting instructions, but is aimed at the knitter who is already competent in working the commonly used stitches.

The intricacy of all the different crossovers and interlocking of stitches may at first appear too complex to work into a fresh Aran design for all but the most experienced of knitters; I hope that this book will allay some of those fears and will enable you to produce Aran knits that you will be proud of and happy to wear for many years. I hope that it will also give you some ideas of how to use Aran stitches to develop new motifs of your own.

CHAPTER 1

HISTORY

In through the front door

Once around the Back

Out through the Window

And off jumps Jack

Anon, an old rhyme used for teaching children to knit

The Origins of Knitting

It is impossible to know the exact history of knitting. Early pieces of knitting were usually made for practical reasons; as they wore out, they would be discarded. They were made from perishable fibres which disintegrate so easily that there are only fragments of fabric to study – no whole pieces. This makes it difficult to discern exactly how they were constructed, or for what purpose. Those items reliably dated as coming from before the eleventh century were most likely made using a technique known as naalbinding, where the yarn was passed in and out of loops made with fingers or a threaded needle. The earliest knitted example of this dates from AD 256 and was found in Syria. It is just a fragment approximately five inches square and there is no clue as to what it was part of. The successor to this technique was the peg loom – a series of sticks held in the hand or mounted on a rectangular block. It was worked as in loop knitting, with the yarn being wrapped around the peg before being lifted over a new strand above it.

From Fisherman’s gansey to cable aran.

There is some speculation that knitting with two needles, in the form that we know it now, dates from well before the eleventh century. This theory arose from paintings of the Virgin Mary apparently knitting a sock. However, these are paintings created in Europe in the fourteenth century and simply prove that knitting was known there at that time, not that is was being created much earlier. The earliest piece of knitting that can be dated and which appears to have been made with two hand-held needles was found in Egypt. It is a pair of socks, elaborately patterned and worked in fine cotton yarn. Some pieces of knitting, silk cushion covers and gloves were also found in 1994 in the tomb of Prince Fernando de la Cerda in northern Spain. Because he died in 1275 and these items were buried with him, their dates are accurate. The pieces are so neat and detailed that it is presumed that knitting had been practised in Europe for a long time before this.

Pieces like these that have been reliably authenticated were usually made for special occasions, especially religious ceremony, and they are fine examples of the craft. Other pieces still in existence were made by craftsmen belonging to the guilds of the Middle Ages. An apprentice would not receive the designation of Master Craftsmen until he had knitted a number of specified pieces. The main piece to be knitted before an apprentice could become a Master was a knitted carpet containing at least a dozen colours, and which was probably intended to be a wall hanging. Other items had to be made following a set of general instructions but not a precise pattern; for example, stockings were to be decorated with ‘clocks’, a form of fine cabling made by crossing or twisting two stitches. These twisted stitches would often form a small rope or diamond shape, demonstrating that crossed stitches were known in Europe in the fourteenth century at least.

Knitted socks and gloves were fairly common throughout Europe and the Middle East at this time. It was easier to use knitted rather than cut fabric because of the complex shaping required to accommodate the fingers and thumb in gloves and the heel shaping in socks, but it took until the fifteenth century for the craft to come to Britain. It was probably spread via the trade routes and was mainly used to make caps and bonnets, particularly in Coventry, Monmouth and Kilmarnock. A guild of hat knitters was established in England, with the aim of standardizing the construction of the various types of hats. The hats were made from wool rather than the silk or cotton used for gloves and stockings, as these hats were not for special occasions but for everyday wear. They were not left in their original knitted state, but were felted to make them more hard-wearing and waterproof.

The changes in fashion from long robes to doublet and hose in the sixteenth century brought about a growth in the sock knitting industry. Long stockings were now favoured rather than short or mid-calf socks. These long knitted stockings had to be tied at the tops because purl stitch, needed to make an elastic rib, had not yet been discovered.

The first pair of knitted stockings to be seen in England came from Spain and were worn by Henry VIII. He favoured them over cloth stockings because they emphasized his ‘well-shaped calf’. They were also much more comfortable than the coarse cloth stockings previously worn. Queen Elizabeth I loved the texture of the silk lace stockings originally sent to her as a gift from France; she had the ladies at court taught how to knit so that they could keep her well supplied. Once royalty was seen to be wearing something, that fashion spread, and eventually the stocking industry became a vital part of the British economy. But stockings were not cheap: the Earl of Leicester paid 53 shillings and 4 pence for a pair of hose, which is more than £500 in today’s currency! However, in 1589 the invention of the stocking frame by William Lee dealt a death blow to this hand knitting industry and many of the great knitting centres of Britain gradually faded away.

The Continuing Tradition of Hand Knitting

Despite the impact of the stocking frame on the British knitting industry, in parts of Britain more distant from the manufacturing towns the practice of hand knitting continued, and it is from here that we get many of our well-known traditions. Handknitted stockings continued to be an important source of income for many people – men, women and children – in the Yorkshire Dales, Scotland and Ireland. In 1588 a knitting school was created in the town of York to teach girls and young women how to make those items that were now turning out to be in great demand. Schools in other parts of the country followed soon afterward. To speed up the knitting process, many of the knitters would work with a knitting stick or sheath attached to their waist. The non-working end of the working needle would be held in place by the sheath so that the hand was free to throw the yarn more quickly. Sometimes a clew holder was also attached to the waist to hold the ball of wool while the knitter walked around.

The fashion for these comfortable handknitted stockings continued, and there was such a demand for wool that villages were destroyed in order to give the land over to sheep pasture. As late as 1805 the export of stockings from Aberdeen alone was valued at £100,000. But as a result of the mechanization of stocking manufacture with the introduction of William Lee’s stocking frame, and also as fashions changed, the boom time came to an end and people began to look for other commercially viable items to knit.

In the more remote parts of Britain men and women continued to knit for themselves and their families the items that were suited to their way of life, the local conditions and the qualities of the wool produced by the local sheep. The sheep of the Shetland Islands, for example, produce wool that is capable of being spun very finely, which led to the production of the famous ‘wedding ring shawls’. The native sheep of Aran and the west of Ireland, similar to the modern Galway breed, produced coarser fleece with hair and kemp that can withstand high rainfall and the Atlantic gales. The wool from these sheep was used to make hard-wearing clothing that was suited to the way of life of the fishermen and farmers.

Typical of these garments was that made famous on Guernsey. Like most areas of Britain, the island originally produced stockings for export, but the French Revolution disrupted this trade and the industry declined. However, the islanders continued to knit sweaters for the local fishermen, as they had done since the sixteenth century when they were first granted a licence to import wool. These sweaters – what we now know as ganseys – were knitted in the round, in the traditional square shape with a straight neck so that they could be reversed as they became worn. They were usually made of heavy, tightly spun worsted wool imported from England and were knitted using fine needles known as ‘wires’, giving a firm finish to the fabric that was said to ‘turn water’. The type of yarn used and the technique of mixing knit and purl stitches also made them warm (combinations of knit and purl stitches side by side trap more air as the loops lie in different directions). This simply shaped garment, possibly based on the traditional linen smock with its patterned yoke, square sleeves and simple shape, was the favourite workwear of many of the coastal communities around Britain and Ireland. They were, and still are, traditionally knitted in the round with dyed navy blue wool. Like the smock, they were usually plain up to the yoke, where they would frequently have a pattern of cables alternated with knit and purl stitches, sometimes with a simple rib and garter stitch pattern at the armhole edge and above the welt.

The simple decoration of a Channel Islands gansey.

The welts would often have side slits for ease of movement, but otherwise these sweaters were constructed in a similar way all around the coast of Britain. They were knitted in the round, to a basic T-shape, with underarm gussets and often one or two purl stitches to mark the position of what would otherwise be side seams. The advantage of being knitted this way was that there were virtually no seams to come undone. The sleeves were picked up from the stitches of the gusset and along the armhole edge and worked downwards, which had the added bonus of making them easy to repair when they were rotted by the salt water.

The Development of Aran Knitting

The three inhabited islands in Galway Bay – Inishmore (Inis Mór), Inishmaan (Inis Meáin) and Inisheer (Inis Oírr) – are mainly formed of limestone rock. There is some fertile ground on the northern sides of the islands, but the rest is barren, often bare rock. The islands are windswept and rocky with just a few inches of topsoil. Because they are cut off from many of the everyday things that mainland people take for granted, island peoples are often resourceful. Necessity is the mother of invention, and the Aran islanders ‘improved’ the scanty soil with the addition of sand and seaweed. The island climate is relatively mild and this ‘home-made’ soil was good enough to produce potatoes and other vegetables, and enough grass for a few sheep to feed on.

The barren coast of Inishmore.

Fishing, as well as farming, was also an important means of providing food for the Aran islanders. The men would fish from small boats, known as curraghs, and there is documentary evidence from photographs published in 2012 of them wearing what look like machine-knitted ganseys similar to those produced by the contract knitters of Guernsey. The men and women on the Aran Islands would copy these square-shaped ganseys, known as geansais in Ireland, and hand knit them, just as they had been accustomed to doing for the stockings and shawls and other warm garments that they made for themselves and their families. They would spin the wool on a Great Wheel and dye the wool intended for sweaters with indigo. There is no evidence of a cream Aran sweater in these pictures, taken in the mid-nineteenth century.

Life was incredibly difficult on the Islands, and as a result of the policies of the government, the farms became smaller and smaller, so were less able to support their inhabitants. In 1886 Father Michael O’Donohue, the parish priest of Aran, sent a telegram to Dublin telling the authorities how difficult it was for the people to sustain a living and that help was desperately needed. His request was heeded and the Congested Districts Board began to stimulate the fishing industry by building piers out from the islands towards the mainland, and by starting a steamer service to Galway. The Board had been set up in 1891 by the government to encourage economic growth and discourage emigration in rural areas where the population had outgrown the productive capacity of the land. By the 1890s, knitting was being actively encouraged on the islands as a viable way of making a living. Now it was the women, rather than the master craftsmen of the guilds, who practised the craft. While the men continued to work on the land and sea, the women took to knitting with great enthusiasm, now that they had an outlet for their work.

This is a replica of the sweater featured in Mary Thomas’ book. It was knitted to a pattern that I designed for the Knitting & Crochet Guild and is in the Guild Collection.

Dr Muriel Gahan (1897–1995) founded her shop Country Workers Limited in 1930 to promote traditional country crafts. She was very keen to keep alive the Irish country crafts, such as weaving, basket making and knitting. She felt that the people who practised these crafts deserved more respect and recognition. In December 1930 she opened the Country Shop in St Stephen’s Green in Dublin as an outlet for the sale of many of the traditional Irish crafts. The shop also contained a restaurant/coffee shop and became a popular place for locals and tourists alike to visit, gossip and shop.

Tourists were keen to purchase the items shesold there, and in order to find more traditional crafts, Dr Gahan visited the Aran Islands in 1935. Through her friend Elizabeth Rivers, an artist who lived on Inishmore, she was put in touch with the knitters in the area and started to buy their unusually decorative sweaters from them. These were the first Aran handknits to go on sale and one of them, displayed in the window of her shop, was spotted by Heinz Edgar Kiewe, a self-styled ‘professor of textile history’. He wrote a paper on his findings in 1966.

Heinz Edgar Kiewe, a man more interested in myth and folklore than in establishing facts through primary sources, owned a wool shop, the Art Needlework Industries in Oxford. Even though he did not present his ‘facts’ as documented evidence, he promoted himself as an expert in the history of textiles. He surmised that knitters were working Aran patterns more than 2,000 years ago. His book The Sacred History of Knitting, which he published in the 1930s, helped to promote the myths and romantic notions of Aran stitches and what he felt was their ancient history. Many of these myths have continued to this day, especially those concerning the ancient clan stitches that supposedly belong to the different families in Ireland. But, as we know now, Aran knitting is not an ancient tradition; it began at the end of the nineteenth century in a bid to relieve the hardship of the poorest families on the islands. The Celtic lands have long been areas of myth and mystery, especially when they are islands! Consequently, there are lots of myths about the origins of Aran knitting and its various motifs.

The use of Celtic knot work decoration was widespread in illuminated religious manuscripts in the seventh and eighth centuries, especially in their carpet pages, which were the full-page illustrations at the beginning of each chapter. Amongst the scrolls and motifs are depictions of fantastic creatures filled with highly decorative motifs, which is where Kiewe claimed to have seen evidence of Aran knitting. All kinds of beasts and artefacts were ornamented with it. But the original Aran sweaters had no such intertwining designs; their decorative stitches were composed of vertical lines and stitches, many of which imitated the shapes of the motifs found on the fishermen’s ganseys. The 1936 sweater that Kiewe saw has a panel of diamonds created in simple moss stitch, but there are no outlining travelling stitches alongside it.

A page from Heinz Edgar Kiewe’s paper presented at Oxford in 1966

Origin of the ‘Isle Of Aran’ Knitting Designs by Heinz Edgar Kiewe, Oxford (Fourth Revised Edition)

Folklorists have a habit of becoming too enthusiastic about insular tradition. Since they usually live in big towns and take the importance of political geography a bit too seriously, they often mix up nationalism with the migration of symbols and designs which is usually inspired by faith and superstition rather than by local genius. Abstract Folk designs of Europe generally came with the pilgrims, missionaries, pirates and/or favourable trade winds to the northern countries from the Eastern Mediterranean where the three great religions were born.

It will be interesting from this point of view to trace the origin of the famous Aran patterns.

We have studied the designs of Aran Knitting for the past 30 years, and it is a curious fact that we must have been the beginners of this interest in Aran Sweaters in England. It was in 1936 to be precise that we purchased a peculiar whiskery looking chunk of a sweater in ‘Biblical White’ at St Stephen’s Green in Dublin. To us it looked at that time too odd for words, being hard as a board, shapeless as a Coptic Priest’s shirt and with an atmosphere of Stonehenge all around it.

We took it to Mary Thomas, our dear friend in London. At the time she was Fashion Editor of The Morning Post and the sight of the hide-like fabric made her most excited. ‘You have found a knitted sampler of Cable stitches,’ the great expert said. ‘May I publish it in my new book?’ She did so in the Mary Thomas Book of Knitting Patterns (page 62).

She described the photo as a ‘magnificent example of “Crossover Motifs” arranged in pattern; it is a classical choice every pattern being of the same crossover family. The knitting is intricate but traditional of Aran and worn by the Irish Fishermen of that island.’

We were most enthusiastic about our discovery for at that time there was only one interlace pattern in the vocabulary of the British knitter and that was the Cablestitch used exclusively on the Jersey-Guernsey Isle by fishermen and for those ‘cricket sweaters’ one of the earliest of handknitted folk designs and common to the English Village Greens of Victorian days. In 1937 we saw the beautiful film Man of Aran by Robert Flaherty, and we made up our mind to help to revive a ‘Biblical White’ Fishermen’s Sweater, kin to sea, storm and tough people. During the War we explored sources for congenial wool of the whiskery type of the natural sheepwool of the Aran Isles used before the War, and today we employ quite an industry of Harris Tweed Spinners on the Outer Hebrides; people who have a closer bond with the folk in Aran than with those in Glasgow, Edinburgh or Liverpool.

Heinz Edgar Kiewe’s theory

Kiewe based his assumptions on pictures from the Book of Kells, where he spotted a small picture of Daniel wearing what he interpreted as a bainin sweater (a sweater made from a specific type of yarn) and a pair of Aran stockings. He attributed the stitch patterns on Daniel’s garments to those motifs found on Celtic crosses and stones, surmising that the people of the Aran Islands must have been inspired by these motifs, incorporating them into their knitting from the time the stones were created. He linked many of the patterns to a religious theme; he saw Trinity Stitch as a symbol of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, the Tree of Life as representing growth, and Ladder stitch as a depiction of Jacob’s ladder linking Earth to Heaven. He explained that the interlinking motifs were associated with the linking of man to God. He had no proof for these theories, and simply asserted that they were more than likely true.

The Origins of the Aran Sweater

Before around the middle of the nineteenth century you would not have seen anyone on the three Aran Islands wearing what we would now recognize as an Aran sweater. They were more likely to be wearing the type of basic gansey pullover described above, found in the fishing communities around the North Sea.

Typical cable patterns found on fishermen’s ganseys around the British Isles.

Knitted sweaters of any kind were not originally part of Aran native dress, as most clothing was made from woven flannel. Samuel Lewis, a publisher of topographical dictionaries, including one for Ireland published in 1842, made no mention of a special type of knitting on the Aran Islands. Like the writer, J. M. Synge, who had a keen interest in customs and folklore, he also noted that some of the younger men were beginning to adopt ‘the usual fishermen’s jersey’ (the gansey, or geansai in Ireland) common around British and Scottish coasts at the time. This is strong evidence that these garments were well known on the Aran Islands.

Synge, and other visitors to the Islands interested in the folklore and customs, took photographs of the people of the West of Ireland and the Aran Isles. Many of the photographs taken by Synge and Alfred Cort Haddon are now kept at Trinity College Dublin, and some of them show Aran men dressed in their navy blue ganseys. A photograph of four Aran men taken in 1910 purports to show that these are examples of sweaters handknitted by the women of the islands. However, on close examination of the photographs, I am sure they are the commercially produced machine-knitted ganseys made by contract knitters in England. I have examined examples of these machine-made ganseys in the museums in Cromer and Sheringham and they are identical. The fact that three of those in the photograph are all identical to each other also proves the case to me.

However, it is undoubtedly true that some skilled women would be able to work cable patterns by hand, and we have Mavis Clark’s recollections to show that this was so. The knitters would increase their repertoire of stitches by copying patterns seen on the ganseys of the boat builders and the women who came with them from England and Scotland to share their skills and stimulate the local fishing industry. This is the strongest evidence to me that the patterns on Aran sweaters originated from the navy blue knitwear already popular among fishermen from Britain, the Channel Islands and across the North Sea.

Photograph of Aran men in their ganseys, taken by J. M. Synge in 1910. Reproduced with kind permission of Trinity College Dublin.

A machine-knitted sweater in Sheringham Museum. With thanks to Ron Wiebe.

Mavis Clark, a fellow member of the Knitting & Crochet Guild who spent the 1940s in the West of Ireland, which is very similar in geological and social terms to the Aran Islands, told me of her aunt, born and bred in Ireland, who had been knitting the familiar cabled yoke pattern on these ganseys since her mother passed it down to her at the beginning of the twentieth century. The photograph shows a reproduction of this pattern that Mavis knitted for the Guild.

The Irish gansey made by Mavis Clark from memory of her grandmother’s pattern.

The pattern set-up is:

Row 1: K2, p2, k2, c4 forward and repeat.

Row 2: P2, k2, p2, p4 and repeat.

Row 3: P2, k2, p2, k4 and repeat.

Row 4: K2, p2, k2, p4 and repeat.

Mavis’ grandfather was a Blackface Sheep farmer. These sheep are similar to the Galway sheep bred on the Aran Islands now. They are a hardy breed and can be sustained on poor soil.

Like Mavis’ aunt, most of the knitters on the Islands would make up their own patterns; they were already skilled at devising stitches and understood how to make the cables turn in different directions.

A pair of handknitted Aran socks in the Collection of the Knitting & Crochet Guild, with lovely 6-stitch rope cables at the cuffs.

Cables were a popular feature of working sweaters; since the 1600s they had been used on socks and stockings, perhaps inspired by those seen on visitors from other parts of the world; cables and travelling stitches were a familiar design on Austrian and German woollen goods. Such stitches could also be produced on a knitting machine, and most of the ganseys produced commercially featured such patterns as those seen in many of Synge’s photographs.

This cream ‘Aran’ jumper only has patterning on the yoke, not all over as we associate with traditional Arans now. Note the buttons on the shoulders to enable it to go over a child’s head more easily and less painfully.

But these commercially produced garments were more expensive to buy and, where families kept their own sheep or could exchange other produce with neighbouring sheep farmers, the women of the Islands preferred to knit their own. Most of the farmers’ wives on the Islands would own a spinning wheel, or they would at least have a close neighbour who did.

While they knitted practical garments for their own families, they could also subsidize their income by knitting socks and ganseys for sale. The patterns were passed on by word of mouth down the generations, so the knitters were already skilled in the working of cabled patterns on ganseys and sock tops. They worked without written instructions, using those stitch patterns that they knew by heart. Many women collected peat to bring home in baskets on their backs, knitting as they walked. Knitting is a skill that needs little equipment; it is a portable craft that can be carried out while doing other tasks. But checking a written pattern every few minutes would be tiresome and make multi-tasking like this difficult.

It is said that there was a tradition for young children to wear white sweaters, rather than the navy blue worn by their fathers, and that more intricate versions of them were worn for First Holy Communions or to Mass on Sundays. But although there are pictures of children in cream or white sweaters, no one has seen photographic evidence of sweaters with the all-over patterning that we associate with Aran knits.

From the middle of the nineteenth century, instruction books for knitting were being widely published in Britain for use in the knitting schools as well as by individuals. They included line-drawn illustrations, which were sometimes a little more fanciful than the actual stitches. Most of these books had descriptions of how to work crossed stitches.

A section of a blanket with an unusual central panel of cable stitches. Reproduced with kind permission of the Knitting & Crochet Guild.

In 1881 The Lady’s Knitting book described the working of a cable thus: ‘Take the next 2 stitches on a third needle, and keep them on the right side of your knitting, knit the next 2 stitches, and then knit off the 2 on the third needle.’

Workers with the Congested Districts Board trained knitters to create complex patterns from these stitches, and instead of the fine, dark-coloured wools traditionally used to make fishermen’s jerseys, the Islanders experimented with soft, thick, undyed yarn, known as bainin (pronounced ‘Baw neen’ and meaning small white), which has a high lanolin content, making them warm even when wet. This thicker wool was knitted on bigger needles, so it was much quicker to produce a garment – an important consideration when making multiple items for sale.

Close-up of moss stitch diamond motifs on white gansey.

As they could already create various cables from the familiar patterns that they used on stocking tops and blankets, they were quickly able to learn other patterns, such as zigzags and honeycombs, by crossing the stitches in a different direction. It would not be too huge a step to devise a diamond pattern from a zigzag, or a braid from a rope-like cable. Diamond patterns in purl stitches were already familiar to them from their ganseys, and the shapes and stitch counts could be translated into knit stitches moving across a purl background instead of purl stitches on a knit background.