10,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Why It Matters

- Sprache: Englisch

History lies beneath our feet and in the landscapes around us. In contrast to the history that comes from studying texts, archaeology is the study of history through objects, monuments, and other traces of past lives: history that extends beyond the earliest writings into the deep past, revealing the varied pathways that led to the present, and the challenges – often similar to those we face today – that confronted our ancestors.

Ann Stahl argues that archaeology is unique in its focus on the everyday lives of all peoples in all places and times. From ancient temples to humble homes, archaeologists piece together worlds that would otherwise be lost: knowledge that shows us how routine actions have shaped societies, how and why societies have changed in light of environment, politics, and culture – and perhaps what the future holds for our societies too.

Using compelling examples from a storied international career, Stahl provides the perfect summary of why archaeology is both a vitally important and enjoyable subject to study.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 150

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

1 Archaeological Perspectives

Notes

2 Time and Knowing

Thinking through Analogy

Other Ways of Knowing

Notes

3 Connections through Things

Engaging the World through Things

Connections through Small Things: Beads as Social Technology

Notes

4 Practice and Knowledge

Knowledge in Practice

Studying Practice

Notes

5 Possibilities

Notes

Further Reading

Studying Things and Doing Fieldwork

Archaeology with Relevance to Contemporary Issues

Iconic Sites and Authoritative Summaries

Careers

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

Figure 1.

Mt. Vesuvius looms over one of many paved streets in Pompeii lined with brick ed…

Chapter 2

Figure 2.

Neolithic polished stone tools. A: Two polished stone celt heads (plan, profile, and …

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of traveling in space (here to there) as a way to imagine th…

Chapter 3

Figure 4.

Figure of a king adorned with beads, Wunmonije site, Ilé Ifè, Nigeria, c. early …

Chapter 4

Figure 5.

White Mountain Redware bowl (St. Johns Polychrome) showing forming and interior de…

Figure 6.

Map of the Poverty Point earthworks site. The earthworks are situated to the west of the …

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Begin Reading

Further Reading

End User License Agreement

Pages

ii

iii

iv

v

viii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

Polity’sWhy It Mattersseries

In these short and lively books, world-leading thinkers make the case for the importance of their subjects and aim to inspire a new generation of students.

Helen Beebee & Michael Rush, Philosophy

Nick Couldry, Media

Robert Eaglestone, Literature

Andrew Gamble, Politics

Lynn Hunt, History

Tim Ingold, Anthropology

Katrin Kohl, Modern Languages

Neville Morley, Classics

Alexander B. Murphy, Geography

Geoffrey K. Pullum, Linguistics

Michael Schudson, Journalism

Ann B. Stahl, Archaeology

Graham Ward, Theology and Religion

Richard Wiseman, Psychology

Archaeology

Why It Matters

Ann B. Stahl

polity

Copyright © Ann B. Stahl 2023

The right of Ann B. Stahl to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2023 by Polity Press

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4988-7

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022939406

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

Dedication

To the next generation, starting with Josephine Ann and Abigail Marguerite White. Know whence you came and learn from the past to create a brighter future.

Acknowledgments

Grateful thanks to colleagues who shared images: Akin Ogundiran for the Ilé Ifè figure; Patricia Crown for the White Mountain Redware bowl; and Diana Greenlee for the Poverty Point base map. I am grateful to the National Commission of Monuments and Museums, Nigeria, for permission to include Figure 4. Thanks too to Peter Stahl for serving as a sounding board for ideas and providing helpful input on content. The book benefited from the constructive suggestions of anonymous reviewers of the volume proposal and manuscript, for which I am grateful.

1Archaeological Perspectives

Go back to where you started, or as far back as you can, examine all of it, travel your road again and tell the truth about it. Sing or shout or testify or keep it to yourself: but know whence you came.

James Baldwin, The Price of the Ticket:Collected Non-Fiction, 1948–1985, (New York: St. Martins, 1985), p. xix

As a girl growing up in an Ohio town on Lake Erie’s south shore, I was fascinated by the contents of a dusty cigar box on a shelf in my father’s garage workshop. It held stone “arrowheads” of varying size, shape, and color. My father collected some from plowed fields around his boyhood home in southeastern Ohio. His father, a ceramic engineer who spent his working life around clay pits and brick factories in the American Midwest, collected others. Some likely came from his maternal great uncle who moved to New Mexico in the 1880s to stake a claim during a turquoise and silver mining boom. Among these was an ancient Clovis spear point, an iconic stone tool that archaeologists associate with the earliest inhabitants of the American Southwest.

I understood these stone objects as things from the past – relics of “Indians” who lived on lands known to my settler ancestors as Ohio. But as a schoolchild, I knew nothing of the Erie people for whom the nearby Great Lake was named, nor of the ancient Indigenous Americans who built the earthworks and effigy mounds that attracted tourists to Ohio’s southern counties. I was unaware that landscapes around me bore traces of generations of Indigenous action, as did the landscapes met by my paternal grandmother’s Puritan ancestors when they arrived on the shores of land they called New England.

Though my Puritan ancestors imagined themselves as settling a wild place in need of taming and fencing, they benefited from landscapes and resources created by generations of Indigenous Americans. The cleared areas where Indigenous Algonkian people grew their staple maize, beans, and squash created edge environments that attracted animals like deer. These clearings also suited the cows and pigs that Puritans brought with them on their ships, particularly so because Indigenous gardens were unfenced. So too did Puritans benefit from Indigenous technologies they adopted for living in a world they called “new.” The earliest Puritan settlers modeled their houses on Algonkian wigwams and borrowed technologies like snowshoes and canoes, vital to the fur trade that sustained their colonies. Puritan survival also depended on growing “Indian corn,” domesticated thousands of years earlier in the neotropics and refined by countless generations of Indigenous farmers. In short, they benefited from infrastructure created and stewarded by Indigenous communities whom the Puritans and later settlers dispossessed and displaced.

This story is not peculiar to America. Wherever we live, the histories of earlier generations lie underfoot and in the landscapes, plants, and animals that surround us. But this is history viewed dimly if at all through the texts that are a historian’s primary sources. Deep-time histories of human-modified landscapes, our relations with plants and animals, our technologies for acquiring food, of creating shelters, our ways of living together in societies small and large – these are subjects for which archaeology provides primary evidence and sheds light on whence we came.

A simple classroom exercise illustrates why archaeology matters. A wide chalkboard provides an ideal canvas, but a sheet of paper turned on its long side will serve. Draw a line edge to edge to represent the time span of human history. Make a mark at one end to represent 3 million years ago, the point by which we know that early human ancestors in East Africa were making stone tools.1 A tick at the opposite end represents today. Make a mark representing .5 million years ago (one quarter the line’s length from “today”). Between .5 million and today, add a tick representing 100,000 years ago and then one at 50,000. Now divide the line between 50,000 years and today with four ticks, the last representing 10,000 years ago. Halve the line between 10,000 years and today. This last tick marks the time around which early writing systems developed in the Middle East, with early writing in China appearing by somewhat over 3,000 and Mesoamerica about 2,500 years ago. Societies across the globe adopted this innovation, though unevenly and some in recent centuries. The point of this exercise? Important as written sources are, they cover less than 1 percent of human history. If we want to learn about the remaining 99 percent, we must draw on other sources.

One possibility is oral history. All societies relay their history from generation to generation, for example as origin accounts, epics, or odes. Once dismissed as unreliable by scholars, oral accounts convey intergenerational wisdom, including memories of times long past. They provide insight into how past experience influenced a society’s values. Oral histories are selective and, in this way, no different from texts. Like texts, they tend to be richer in reference to recent times, but they can be important sources of historical understanding, and particularly so for societies that emphasize oral literacy.2

Archaeological evidence also has limitations. Its material sources are biased toward durable (stone, metal, ceramic) technologies over perishable ones (basketry, cloth). Accurate interpretation requires close attention to how objects came to rest in the ground and whether their context was disturbed afterwards. But from the time when our hominin ancestors began to make, use, and discard stone tools, material remains in the form of what archaeologists call artifacts (things made or modified), ecofacts (resources like plants and animals used or modified by people), features (modifications of the earth’s surface by digging, mounding, building) and their associations (spatial relations or context) provide valuable evidence for understanding past lifeways. By focusing on material remains and their contexts, archaeological methods and techniques extend historical understanding to any time or place in which we find traces of people interacting with things and surrounding landscapes. This applies equally to times “covered” by writing: archaeology lends insight into aspects of life and the lives of people not described in texts. It can also challenge what we learn from written sources. For these reasons and more, archaeology matters.

A young person today is more likely to be introduced to archaeology through a video game than an arrowhead collection, but its lure and fascination remain. Films and gaming portray archaeologists as treasure hunters and tomb raiders in search of powerful relics and ancient secrets. These adventurers succeed while narrowly escaping threats: the undead, hostile natives, or rival archaeologists. For the record, I have never had to outrun a thundering boulder while doing archaeology, nor is a bullwhip part of my tool kit. But real-world archaeology holds a fascination nonetheless, appealing to public curiosity about the past as demonstrated by the success of periodicals like the National Geographic or Archaeology magazines and a steady flow of documentary films. Though platforms like these only sample the range of what archaeologists do and how they contribute, they attest to a widespread public curiosity about archaeology’s subject matter.

On the subject of stereotypes, let’s set aside another. Archaeologists do not dig up or study dinosaurs. That is the work of paleontologists. Their timeline requires an even wider classroom chalkboard!

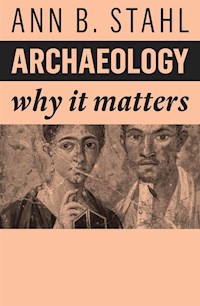

So how can we characterize archaeology? In keeping with popular imagery, it can be exciting, if in a more garden-variety way than depicted in Raiders of the Lost Ark or Lara Croft: Tomb Raider. Whether digging in a garden, walking a plowed field, or participating in a research excavation, there is wonder in finding old things. Being the first to see or handle an object untouched for centuries or millennia can be thrilling. Perhaps you have had the privilege of visiting one of many iconic sites around the world: Stonehenge in England, Egypt’s Giza Pyramids, Chichén Itzá in Mexico, Machu Picchu in Peru, Cambodia’s Angkor Wat, southern Africa’s Great Zimbabwe, or the terracotta army of Emperor Qin Shi Huang in China, among many others. If so, you know first hand the frisson of being among awe-inspiring monuments and the handwork of ancient people. Walking the streets of Pompeii, made accessible through the work of generations of archaeologists (Figure 1), we marvel at the scale and preservation of the ancient Roman city. We feel goosebumps under the gaze of baker Terentius Neo and his wife, captured in a fresco found in their Pompeii workshop home and reproduced on this book’s cover.

Figure 1. Mt. Vesuvius looms over one of many paved streets in Pompeii lined with brick edifices of ancient Roman buildings that are open to tourists. The baker Terentius Neo and his wife, pictured on the front cover of this book, might have walked these streets on a daily basis. Photo by the author.

Archaeologists are puzzle solvers, though not of the kind that unlock ancient tombs. Our puzzles involve piecing together clues from finds and their contexts to lend insight into past lifeways. Anyone who has paused to watch an excavation in progress will know that the work is time-consuming, painstaking, and more often tedious than exciting. Even more so the lab work that follows as archaeologists count, weigh, measure, and otherwise describe and analyze excavated materials.

Our puzzle solving is akin to assembling a jigsaw puzzle without the aid of the finished picture. This is particularly so for archaeologists working in regions with little prior research or in contexts where other sources (written, oral) are unavailable. Where we dig – in a temple, a palace, a humble household, or a garbage heap – and how much we dig determines which puzzle pieces we have to reconstruct the wider “picture.” We never have all the pieces. We work with samples, from which we make wider inferences and claims. The quality and number of our samples have implications for the reliability of our insights about a region or period, which is one of the reasons why ongoing research can spark vigorous debate and change what we know about the past.

If you are a jigsaw enthusiast, you know how joining the wrong pieces stymies your progress. Our views of the big picture often run in advance of the puzzle pieces, creating hunches or hypotheses about what to look for among remaining or future ones. Sometimes these hunches are wrong. Being open to clues lent by new pieces helps us to reform interpretations and understandings. As we will see, archaeological evidence can reveal startling insights that force us to reconsider what we think we know about the past, so long as we remain open to considering its surprising implications.

Our puzzles vary in scale and resolution. Some archaeologists spend their careers puzzling over a single artifact type, site, or region. Others puzzle at wider scales – focused on longer units of time or wider landscapes. The pace of archaeological research has accelerated over recent decades to the point that keeping up with current research outside one’s specialist area is daunting. For this reason, among others, global and popular syntheses of archaeology often lag behind the current state of research and perpetuate outdated understandings of human history, a point to which we return in pages to come.

Because it requires many human resources, archaeology is expensive and often depends on government research or non-profit funding. Volunteers or students-in-training who pay to participate are the lifeline of many archaeology projects. In countries where governments struggle to provide basic services to their citizens (in other words, much of the world), the cost of research means that archaeological projects are often funded by foreign agencies and staffed by archaeologists from elsewhere. The same can be said for archaeology in the settler states that encompass all of the Americas, portions of the Pacific, and some African regions. Here the history underfoot is that of people dispossessed and displaced from their ancestral homes and marginalized within those states, few of whom have sought careers in archaeology until recently.

In this and other respects, archaeology is colonial. While societies the world over and through time have demonstrated interest in ruins and old things, archaeology’s disciplinary history is intertwined with imperial expansion and colonialism. Early studies and collecting of ancient Egyptian antiquities took place during Napoleon’s 1798–99 Egyptian campaign and those materials remain in