14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Hatje Cantz Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: E-Books

- Sprache: Englisch

The architecture in Burma represents a mixture of the country's history, politics, natural assets, religion, and superstition. Despite some recent advances toward modernization, in architectural terms, centuries of relative seclusion have caused this country to remain something of a historical timeline. Burma's resplendent temples, stately colonial edifices, and myriad of structures that comprise innumerable fishing and country villages provide an architectural window into the country's diverse and oftentimes tumultuous history. The turbulence of the region, punctuated by dynastic squabbles, is perhaps best chronicled and understood by way of its architecture. The escalation of successional quarrels frequently resulted in new rulers packing up entire palaces and other structures and hauling these by elephant to establish a new seat of government or capital elsewhere. The vestiges of the old cities were for the most part simply left to the vicissitudes of nature.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 161

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

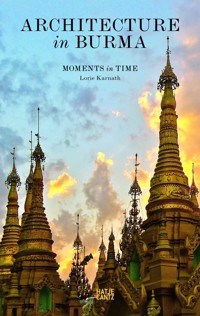

The luminous Shwedagon Pagoda, a compilation of centuries, hovers above Yangon

PRELUDE

The architecture in Burma represents a syncretic mixture of the country’s unique history, politics, natural assets, religious beliefs, and superstitions. Despite some recent inevitable affirmations toward modernization, centuries of relative seclusion have enabled this country to remain something of a historical timeline presented in architectural terms. Burma’s resplendent, mystical temples, stately colonial edifices, and the myriad of structures that populate innumerable fishing and country villages provide windows that reflect the country’s varied and oftentimes tumultuous history. It is through such references to Burma’s past that one may become acquainted with its present. The persistent turbulence of the region is perhaps oftentimes best chronicled and understood through its architecture, as the escalation of successional quarrels repeatedly would result in a new ruler packing up palaces and other structures and hauling these by elephant to establish a new seat or capital. The plundered remnants of the discarded cities left behind have mostly been forsaken except by the ravages of nature. They now serve as historical markers to moments in time.

When discussing architecture or anything else in Burma, names of places represent something of a conundrum, for there is as of yet no stringent formal transliteration from the Burmese language to English, leading to many different spellings of names, locations, and designations. As “Burma” represents the more widely recognized nomenclature for the country, and variations using this name have been in use for a longer period of time, the country is referred to as such throughout the following texts, and names of regions, cities, and towns whenever possible are referred to by their more modern appellations.

Temple compound, Nyaung Kan village; alabaster profile of Yoke Sone Monastery, Salay

Students of the Tharyargone School proceed to the lunchtent outside Yangon; detail of a gold leaf offering bowl

A village scene; elephants aid in procuring teak harvest on Phaungbyin-Homalin Road near Nathmaw

Shwe Palin Pagoda emerging from the mist along the Chindwin River

MOMENTS IN TIME

For centuries, Burma served as an advantageous crossroads both in terms of geography and trade, linking diverse and far-ranging regions, civilizations, and cultures, fortuitously embedded between two of the most historically prolific trading partners: to the north and east lies China, while India fronts a portion of its western border. Furthermore, the country’s strategic coastline allowed for access by sea toward much of the rest of the world. The country’s enviable positioning coupled with a profusion of natural wealth attracted many of varied ethnic origins seeking to stake out both commerce and territorial conquests, resulting in a historically unique and complex melding of beliefs, customs, and styles.

Much of Burma’s colorful history may still be evidenced through its architecture, represented not only in terms of what remains but also by what no longer exists. While in many parts of the world demolition of noteworthy architecture has been predominantly instigated by growth and urbanization, development due to economic demand remains as of yet relatively negligible in Burma. However, Burmese architecture in recent times has in some instances undergone similar pressures, most notably in Yangon, Burma’s former capital and the largest city in Burma today. The country’s decades-old virtual paralysis in economic terms has proven an effective means of ensuring a kind of preservation of old structures, due primarily to lack of call for new facilities. As a result, Burma can claim the greatest number of nineteenth and twentieth century constructions in Southeast Asia, although the majority of these are in dire if not in many cases irredeemable condition. Efforts underway to unlock the country from a long period of isolation have as yet proven elusive for significant growth, although going forward are ostensibly poised to do so. Rather, for the most part, both architectural demise and redemption in Burma reflect and incorporate its long, habitually fractious, albeit storied history. One that is punctuated to this day by a tapestry of ethnic tribal conflicts and conjoins.

Burma’s distinct confluence of natural advantages and geographic proclivities, religious persuasions, superstitions, origins, and politics, has served to play a significant role in the country’s architectural history. The country is represented by several topographically distinct regions, the individual features of each having impacted the architectural direction of the whole. A tangle of waterways function to this day as both a means to access, as well as help ensure separation of, many of its tribal regions. The river system contributed toward tactically influencing the region’s mode and methods of population. The vastly differing patchwork quality of the country’s topography has contributed in some cases to a paucity of ethnic amalgamation further exacerbated by this geographical provision that enables resistance to outside pressures. The varied terrain beyond its obvious sensory attributes tenders a plenitude of mineral and natural resources. These natural riches have also lent considerable influence to the ways and means of the country’s development.

The relative seclusion of the country for almost half a century has precluded significant archaeological analysis utilizing modern scientific methods and technologies. Although work is currently underway, many clues to Burma’s prehistoric past are still tantalizingly being pieced together, numerous diverse details and understanding of events are unfolding. Even so, there are clear indications of primitive societies of Homo sapiens within the region as early as 11,000 BCE. It appears that these ancient residents included cave dwellers as evidenced in particular by three caves situated along the rim of the Shan Plateau, a crystalline massif that forms the eastern portion of Burma and is bounded on its western flank by the Ayeyarwady River. Within the caves can be found wall paintings of red ochre, depicting animals such as deer, bison, fish, and bulls, human hands and symbolic motifs, which have been dated between 11 to 6,000 BCE and ostensibly signify the use of the grottos for ritualistic ceremony. This evidence of early employment of devotional cave worship is an aspect of devotion that continues to serve in Buddhism, implying a connection between earlier animistic and superstitious ritual and the later development of Buddhist beliefs. Caves replete with Buddhist images abound as places of sacred significance, and some natural caves were consecrated within early temple constructions. Certain Buddhist temples were even accorded architectural features to emulate the dim and mystical aspects of a grotto.

The copious availability of minerals and metals would also contribute to the direction and development of distinguishing architectural inclinations. By circa 200 BCE a tribal group known as the Pyu, believed to be among the earliest of Burma’s occupants, began to relocate southward from what is present day Yunnan in China, infiltrating the upper expanses of the Ayeyarwady valley. These Tibeto-Burmese speaking peoples went on to populate the plains region, another well-placed tactical seat outlined by the joining of the Chindwin and Ayeyarwady rivers, two of Burma’s four principal waterways. The Pyu’s expansionist territorial claims proved well considered as these presided profitably along the overland trade route between China and India. Exchange of goods, particularly for Indian imports, proved popular, and soon Indian architectural influences, in addition to religious concepts (namely Buddhism) as well as cultural traditions and political models, began to infiltrate Pyu traditions.

Traditionally gifted artisans: examples of ornaments crafted from palm leaves, Hlaing Toddy Palm Farm, Bagan; along the Ayeyarwady, still one of Burma’s principal transport routes

The Pyu reign is often historically referred to as the Pyu millennium, as it survived from the second century BCE until about mid-century 11 BCE. This period provided many roots that served in the development of the region’s archaeological and architectural base. During this time a number of what have been termed “city states” represented by walled cities were created, heralding the commencement of development and urbanization in the country. Many of the construction templates and innovative building techniques devised by the Pyu would generate a long-lasting impact on the direction of Burmese architecture, and the adoption of Buddhist beliefs would spur the building of religious edifices. Initially, the cities and towns developed by the Pyu were concentrated in upper Burma. However, inspired by the benefits of the riches of their lucrative trading activities, the Pyu, out to capture a greater portion of these, set their sights on grander territorial domains, staking out a much larger city state that was known as Halin and which was established in the first century CE along upper Burma’s northern border. For several centuries, this city would serve as both an ornamental and a powerful constituent in the realm of the Pyu claims. However, the Pyu’s city planning and architectural talents were provided an even greater showcase when, in later times, they established a new capital, Sri Ksetra, known as the “city of splendor” along the southern rim of upper Burma, in this way encapsulating both borders of upper Burma’s important trade routes. Sri Ksetra is believed to have represented the largest metropolis in Southeast Asia at one point, boasting walls that enclosed a circular city representing close to forty-six square kilometers in area. The massive development purported to represent a model of modern self-sustainability as discovered through investigation of the city ruins. The residual structural remnants and remains of irrigation systems provide evidence of numerous religious structures, varied ritual buildings, as well as both farms and housing within the city walls, allowing for significant, albeit confined autonomy.

Antlers and Buddhas line the walls of Yoke Sone Monastery, Salay; Burmese legends depicted in a village monastery outside Bagan

Excavations of a number of the Pyu city states have unveiled archaeological remains that point toward a progressive combination of original design as well as incorporation of outside influences. The structure, planning, and functionalities of Pyu cities were to serve as the template for future Burmese palaces and metropolises. These early cities were bordered by rectangular or square exterior walls, interspersed with twelve enormous gates, representing each of the signs of the zodiac, a format believed to be borrowed from Indian design. The surrounding enclosures beyond, providing service as protective measures, became viewed in some respects as a banner of import, the magnitude of which providing an indicator as to the level of critical importance of the city they enclosed. The massive ramparts, which are estimated in most cases to have ranged between two to five meters in width and may have reached heights as lofty as five meters, were commonly crafted of brick that were additionally fortified through embankments made from earth. Bricks, often marked with pattern, were also utilized for the construction of inner walls, the palace, and ceremonial, religious, and other structures.

To fabricate this massive amount of brick required that huge tracks of land be exhumed in order to provide sufficient soil for clay, these excavations leading to the development of depressions that could be fashioned as reservoirs and moats. The outside walls enclosed concentric interiors, this novel mapping of cityscapes in circular configurations are credited as an innovation of the Pyu Dynasty. A number of other important building directions and advances took place under the Pyu—it was during this period that water logistics, such as dam building, canals, and other water control and disbursement methods underwent significant development and became systematized.

View from Tant Kyi Taung Pagoda: one of four designated resting spots for sacred white elephants, Bagan; innovative fivesided Dhammayazika Pagoda, awaiting the next appearance of Buddha, Bagan

Htoakkan Sima Pagoda, Mrauk U; remnant of volcanic-lava-glazed tile, Bagan

Furthermore, the Pyu’s adoption of Buddhism by the fourth century changed the tenor of building primarily for provisional and utilitarian purposes by fostering their building of stupas and other religious monuments. Construction techniques and materials used for building again evidence a strong connection to Indian as well as possibly some Ceylonese influences. These early religious shrines built during the Pyu period were to significantly inspire later temple building techniques under Burmese rule.

While the Pyu were busily growing their northern empire, another ancient ethnic group, the Mon, aimed toward Burma’s more southern regions for settlement. The Mon migrated perhaps as early as the sixth century CE, traveling in a westerly direction, now present-day Thailand. The Mon also appear to have met with trading success in Burma and ambitiously began setting up their own city states along Burma’s southern rim. By the ninth century it is held that the Mon established a political seat in the proximity of strategic shipping ports accessing the Indian Ocean along the trajectory to mainland Southeast Asia. The Mon also adapted the Pyu practice of building walls from brick.

The Mon are among those directly credited with helping to nurture and disperse in Burma and elsewhere observance of Theravada Buddhism, today considered the oldest enduring Buddhist branch. As a means of furthering the message and teachings of the Theravada doctrine, the Mon began building pagodas and shrines as places for worship and edification. Recognized as gifted artisans and craftsmen, the architecture of Mon-built Buddhist temples include numerous original and distinctive characteristics, as well as creatively incorporating features observed in Indian and other foreign constructions. The unique imprint of the Mon architectural designs secured enduring influence, as numerous Mon artisans highly valued for their talents were eventually conscripted to help erect many of the especially notable religious shrines in Bagan and surrounding areas built under the Bagan Dynasty and Empire.

Stone construction of Shitthaung Temple, Mrauk U; ancient brick-crafted Tharabar Gates credited to the Pyu, Bagan

Though historical evidence suggests that while some early Bamar, also referred to as Mranma or Burmese, migrants appear to have meandered their way south from the present-day Yunnan region as early as the seventh century, it was not until the beginning of the ninth century that they landed in much larger numbers. The Burmese eventually staked out territory in the vicinity of what is now called Bagan (or Pagan) that functioned as their stronghold and was preemptively positioned along the convergence of Ayeyarwady and Chindwin River waterways, which had served as central arteries for the Pyu. From there, the newly ensconced residents expanded their settlement, casting their net ever wider and gradually absorbing surrounding regions. By the mid eleventh century, the Bamar had gained control and the Bagan Empire was founded in 1044 under the progressive leadership of King Anawrahta, considered the “father” of Burma. It is upon Anawrahta’s assent as ruler of the Bagan Empire seat that Burmese history formally begins.

Upon accession, Anawrahta Minsaw skillfully maneuvered and cultivated the development of the minor principality in upper Burma, successfully uniting for the first time the whole of the formerly fractious Ayeyarwady valley. He additionally engendered that other key ethnic bastions, the Shan States and northern Rakhine be placed under Bagan dominion, forming what became the framework for the Burmese nation. This amalgamation of cultures would lay the geographic foundation as well as establish many of the philosophic values and principles of what would evolve to become modern-day Burma. During the period of Anawrahta’s reign a number of vital reforms and restructurings were instituted. Under this empire, which lasted until 1287, the Burmese ethos and language began to predominate over those of the Pyu and Mon, although traditions, religious and political concepts, as well as artistry from both of these ethnic groups would be absorbed and assimilated into the newly developing Burmese culture and even into regions beyond.

This period of evolution amid relative calm under the Bagan Dynasty began to disintegrate by the mid-thirteenth century in large part due to the ability to donate wealth and landholdings tax-free for religious purposes. The Bagan Empire fostered the further embrace of the tenets of Theravada Buddhism, which had by this time gradually filtered throughout the merged region, although remnants of other Buddhist creeds, Indian religions, and even animistic observances were often practiced alongside this. Under Buddhism, it is through a cumulative merit system that one seeks to attain a higher state of enlightenment toward the ultimate goal of nirvana. Merit is attained as a consequence of actions and good works that benefit other beings. Such beliefs have had a profound impact on religious architecture in particular.

This epoch represented a golden period of architectural achievement, in part literally, as many of the thousands of shrines built during this time housed, or were at least partially swathed in, gold. The gilding glittered among a sea of candescent green tile works for which the temples of the period were particularly noted, the luminous glaze crafted from ground volcanic lava rock composed primarily of basalt and basaltic andesite from nearby Mount Popo. That so many religious monuments were constructed within the expanse of a few centuries in and of itself represents an astronomically technological feat of architectural achievement. The Bagan period is credited with a number of innovations and advancements relating to structural design. In particular, furthering the art of using arches and vaulting to allow for the building of increasingly ambitious chambers for the hollow temple style that allowed entry was refined during this time. That arch and vaulting technology was significantly advanced under the Bagan reign seems fairly certain. Prior to this its use was determined in a more nascent format in Pyu architecture among the early engineers of this innovative concept. Already by the eleventh century, numerous sophisticated examples of arch and vault techniques appear in the Bagan region, whereas the use of vaulting in neighboring lands does not appear until later. Such technique does not show up extensively before the late twelfth century in India, for example. It is also during the Bagan reign that Buddhist temples appear to have first incorporated a pentagonal footprint in reverence of the four Buddha who had already emerged, as well as in anticipation of the next to come.

View of Bagan’s temple-sprinkled plains

The construction of such a prolific number of religious edifices represented a significant transfer of capital toward the religious realm, requiring demand for huge labor pools to complete the task of building and maintaining these structures. This transference of wealth enabled the religious sector to ably compensate and to offer further opportunities for merit for such services. However, the eagerness to donate to religious causes served to gradually erode the royal treasury, further exacerbated due to a lack of commercial expansion. It is estimated that more than a third of upper Burma’s agriculturally productive land had been dedicated to religious causes by the time of the empire’s demise. This reallocation of land and depletion of monetary intake also increasingly hindered the crown’s ability to marshal and retain help both for the court as well as for the military. The fifth Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, Kublai, recognized the weakening of Bagan as an opportunity and requested Burma’s submission. Repeated Mongol incursions succeeded in overthrowing the empire in 1287. The end of the Bagan Empire brought forth centuries of turmoil and reduced the once flourishing metropolis of an estimated 200,000 inhabitants to a fraction of its population.

Religious structures in Burma retain a vast amount of the country’s wealth

Seeking merit at Shwedagon Pagoda, Yangon; nun prays atop Tant Kyi Taung Pagoda, Bagan