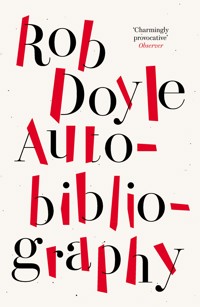

9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'Charmingly provocative' Observer 'A smorgasbord of delights' Irish Times 'Addictive … a writer living and thinking his way to the frontiers of human society' The Spectator InAutobibliography, Rob Doyle recounts a year spent rereading fifty-two books – from the Dhammapada and Marcus Aurelius to Robert Bolaño and Svetlana Alexievich – as well as the memories they trigger and the reverberations they create. It is a record of a year in reading and of a lifetime of books, by one of the most original and exciting writers around. Reader Reviews 'Enlightening, engaging and fun' 'A *superb* gift for any bookish friend or relative with an eye for the human comedy' 'A page-turner ... bright and fresh'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 231

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Also by Rob Doyle

Here are the Young MenThis is the RitualThreshold

To Roisin, and to my Berlin friends

The confused medley of meditations on art and literature in which he had indulged since his isolation, as a dam to bar the current of old memories, had been rudely swept away, and the onrushing, irresistible wave crashed into the present and future, submerging everything beneath the blanket of the past, filling his mind with an immensity of sorrow, on whose surface floated, like futile wreckage, absurd trifles and dull episodes of his life.

J.K. Huysmans

I even remember the colour of the Mexican sky during the two days it took me to read the novel.

Roberto Bolaño

Contents

Introduction1 Svetlana AlexievichThe Unwomanly Face of War Blackened books lay in pools of water2 Roberto BolañoAntwerp A friend3 Fyodor DostoevskyNotes from Underground Latency period4 Marguerite DurasPracticalities In the nineteenth arrondissement5 Arthur SchopenhauerEssays and Aphorisms Feeling chastened, sheepish6 Virginia WoolfA Room of One’s Own It’s springtime and I’m alone7 Arthur KoestlerThe Gladiators Paperbacks that had been left behind8 Friedrich NietzscheOn the Genealogy of Morals Turin9 Jean BaudrillardAmerica I could get by on very little10 Geoff DyerBut Beautiful Incredibly stalkerish11The Tibetan Book of the Dead Gorgeous psychedelic kids12 Philip K. DickValis The body doesn’t last13 Jean RhysQuartet Sleep with writers14 Ursula K. Le GuinThe Dispossessed Punks15 Norman MailerThe Fight Kanye West16 J.K. HuysmansÀ rebours An eagle soars past17 Annie DillardHoly the Firm Other beaches from past lives18 Susan SontagAgainst Interpretation and Other Essays 8A Stock Orchard Crescent19 Georges BatailleErotism Grave and caustic Europeans20 Nathalie SarrauteTropisms Manias of youth21 E.M. CioranThe Trouble with Being Born Waking each morning to ask himself whether he had anything to say22 Angela CarterThe Bloody Chamber So Help Me God23 Alexander TrocchiCain’s Book A dilapidated house in the middle of an industrial estate24 Marcus AureliusMeditations Ruins monumentally propped against a brilliant August sky25 Michel HouellebecqWhatever An imperilled libido and the bodies of nubile girls26 Clarice LispectorÁgua Viva I think she even learned Portuguese27 Sigmund FreudCivilisation and Its Discontents A widespread intensification of dream life28 Terence McKennaThe Archaic Revival A basement bar in La Paz29 Thomas BernhardWoodcutters Slinky dialectics30 Valerie SolanasSCUM Manifesto The creator of hells31 André BretonNadja America and its landscapes32 Sadie PlantWriting on Drugs I heard about his death via a late-night text33Dhammapada At weekends he drank copiously34 Milan KunderaThe Art of the Novel Japan35 Emmanuel CarrèreThe Adversary An Islamic nasheed played backwards36 Stefan AustThe Baader-Meinhof Complex Blind maw of insatiable craving37 Maureen OrthVulgar Favours Do I care?38 Martin AmisLondon Fields The vines in the back garden creeping over her window39 Joan DidionPlay It As It Lays Other pilots began to break formation40 David MarksonReader’s Block Nerve-wasting coffee from a machine41 Herman MelvilleMoby-Dick; or, The Whale Red silk scarf42 Antony BeevorStalingrad I took a Valium and lay on the beach43 Virginie DespentesBaise-Moi Flowers outside the Carillon bar44 Max FrischFrom the Berlin Journal The rattle of pills as they scatter on the floor45 La RochefoucauldMoral Reflections or Sententiae and Maxims Subterfuges46 Carl JungMemories, Dreams, Reflections Memories of the future47 J.G. BallardThe Atrocity Exhibition Sit back in the atomised crowd48 Saint AugustineConfessions Violating my standards faster than I can lower them49 Jorge Luis BorgesFictions Latin America50 Marilynne RobinsonThe Death of Adam Monster51 Albert CamusThe Fall Scenes flung haphazardly together52 Henry MillerThe Colossus of Maroussi Sparkle on a calm seaContents

Introduction

1 Svetlana Alexievich • The Unwomanly Face of War (1985)

2 Roberto Bolaño • Antwerp (1980)

3 Fyodor Dostoevsky • Notes from Underground (1864)

4 Marguerite Duras • Practicalities (1987)

5 Arthur Schopenhauer • Essays and Aphorisms (1851)

6 Virginia Woolf • A Room of One’s Own (1929)

7 Arthur Koestler • The Gladiators (1939)

8 Friedrich Nietzsche • On the Genealogy of Morals (1887)

9 Jean Baudrillard • America (1986)

10 Geoff Dyer • But Beautiful (1991)

11 The Tibetan Book of the Dead • (eighth century ad)

12 Philip K. Dick • Valis (1981)

13 Jean Rhys • Quartet (1928)

14 Ursula K. Le Guin • The Dispossessed (1974)

15 Norman Mailer • The Fight (1975)

16 J.K. Huysmans • À rebours (1884)

17 Annie Dillard • Holy the Firm (1977)

18 Susan Sontag • Against Interpretation and Other Essays (1966)

19 Georges Bataille • Erotism: Death and Sensuality (1957)

20 Nathalie Sarraute • Tropisms (1939)

21 E.M. Cioran • The Trouble with Being Born (1973)

22 Angela Carter • The Bloody Chamber (1979)

23 Alexander Trocchi • Cain’s Book (1960)

24 Marcus Aurelius • Meditations (c. ad 160–181)

25 Michel Houellebecq • Whatever (1994)

26 Clarice Lispector • Água Viva (1973)

27 Sigmund Freud • Civilisation and Its Discontents (1930)

28 Terence McKenna • The Archaic Revival (1991)

29 Thomas Bernhard • Woodcutters (1985)

30 Valerie Solanas • SCUM Manifesto (1968)

31 André Breton • Nadja (1928)

32 Sadie Plant • Writing on Drugs (1999)

33 Dhammapada (estimated first century bc)

34 Milan Kundera • The Art of the Novel (1986)

35 Emmanuel Carrère • The Adversary (2000)

36 Stefan Aust • The Baader-Meinhof Complex (1985)

37 Maureen Orth • Vulgar Favours: Andrew Cunanan, Gianni Versace, and the Largest Failed Manhunt in U.S. History (1999)

38 Martin Amis • London Fields (1989)

39 Joan Didion • Play It As It Lays (1970)

40 David Markson • Reader’s Block (1996)

41 Herman Melville • Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (1851)

42 Antony Beevor • Stalingrad (1998)

43 Virginie Despentes • Baise-Moi (1994)

44 Max Frisch • From the Berlin Journal (1973–4)

45 La Rochefoucauld • Moral Reflections or Sententiae and Maxims (1678)

46 Carl Jung • Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1961)

47 J.G. Ballard • The Atrocity Exhibition (1970)

48 Saint Augustine • Confessions (c. 400)

49 Jorge Luis Borges • Fictions (1944)

50 Marilynne Robinson • The Death of Adam: Essays on Modern Thought (1998)

51 Albert Camus • The Fall (1956)

52 Henry Miller • The Colossus of Maroussi (1941)

Acknowledgements

Introduction

In her book The Writing Life, Annie Dillard asks what it means to live a good life. ‘There is no shortage of good days,’ she writes. ‘It is good lives that are hard to come by… Who would call a day spent reading a good day? But a life spent reading – that is a good life.’

There’s something to this. Holding a characteristically gloomier view, Michel Houellebecq insists in his revering study H.P. Lovecraft:Against the World, Against Life,that ‘Those who love life do not read. Nor do they go to the movies, actually. No matter what might be said, access to the artistic universe is more or less entirely the preserve of those who are a little fed up with the world.’

There’s something to this too. In my case, reading has always served a dual purpose. In a positive sense, it offers sustenance, enlightenment, the bliss of fascination. In a negative sense, it is a means of withdrawal, of inhabiting a reality quarantined from one that often comes across as painful, alarming or downright distasteful. In the former sense, reading is like food; in the latter, it is like drugs or alcohol.

Throughout 2019, I contributed a weekly books column to the Irish Times. The premise was simple: every Saturday I would write about an old book of my choice. The newspaper’s literary editor published the column with the alternating tag lines ‘A year of Rob Doyle’s best-loved books’, and ‘Rob Doyle’s year of rereading’. The only rules were that I had to choose books written before the twenty-first century, and I had to keep my articles to a word limit of 340. While the latter constraint was often frustrating, I viewed it as a stimulating formal challenge. Could I say something fresh and illuminating about a given book, or at least interestingly convey my enthusiasm, on such a modest canvas? Could I capture something of a book’s essence, reflect a sliver of its tone and atmosphere, and not waste everyone’s time by merely writing a glorified summary? Discussing a tome like Moby-Dick at such brevity bordered on the absurd, but the word count forced me to pare down my insights – more to the point, my passions – till they attained, I liked to think, the book-chat equivalent of haikucondensation.

I wrote the column while I was living in Berlin and on a hiatus from social media, so for much of the time I had no sense of what kind of response it was eliciting. In the autumn, I briefly returned to Dublin to give readings at book festivals. At these events, readers approached and told me they had been following my column. Some of them remarked on the relatively low proportion of fiction I selected, which they found surprising considering that that was the genre in which I had established myself as a writer. True enough, of the fifty-two entries, only twenty-three cover works of fiction – and even among these lie a number of generically contestable works (is Alexander Trocchi’s Cain’s Book fiction or memoir? Is Geoff Dyer’s But Beautiful a book about jazz that employs fictive elements, or a fictional work that happens to tell us something about jazz? Is André Breton’s Nadja really a novel? What about Clarice Lispector’s Água Viva?).

While the project was conceived as a corralling of the books that shaped me as a writer and as a man, it also inevitably reflected my present interests as a reader, and I simply don’t read as many novels as I used to. When I was in my twenties, novels were my staple, the primary means by which I understood the world and my place in it. Nowadays, novels are more like the dessert: the main course is large helpings of non-fiction, including criticism, philosophy, aphorisms, history and books about what the internet is doing to me. I have an unslakable thirst for autobiographical writing of all sorts, including diaries and letters. In general I have a predilection for novels that don’t act like novels – the sort of generically slippy works mentioned above. Regardless of genre, I read for delight and fascination even when these sensations demand a toll, opening old wounds or inflicting new ones. The column is a record of sometimes masochistic enthusiasms.

The oldest work I discuss, the Dhammapada, dates back to the first century bc. Chronologically speaking I then skip to the second century ad (Marcus Aurelius), then on another couple of hundred years to the fifth century (Saint Augustine). I then take a running jump from the eighth to the seventeenth centuries (TheTibetan Book of the Dead to La Rochefoucauld), before landing at the commencement of modernity in the nineteenth century. The majority of the books I selected – forty-two of them – were written in the twentieth century, beginning in 1928 and streaking right to the millennial threshold. In fact, I cheated a little with Emmanuel Carrère’s The Adversary, which was published in 2000 – I just really wanted to write about Carrére. I also cheated, slightly and for the same reason, with Roberto Bolaño’s Antwerp, in that I dated it from the year when it was written (1980) rather than the year it was finally published (2002).

I dispute Martin Amis’s assertion that we read even the classics in translation reluctantly. To me, reading a book from a familiar culture can feel like a drab sojourn in some rainy Dublin suburb, when I might travel instead to a far-off country. There are books here by authors from Russia and Asia, South America and North Africa, the United States and the United Kingdom, Germany and Switzerland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, fin-de-siècle Austria and ancient Rome, along with a disproportionate number of books by French writers. The nationality most conspicuous by its absence is the Irish. This is not out of perversity or national self-abnegation on my part, but because, shortly before commencing the column, I had finished editing an anthology of Irish literature: as a reader I wanted to wander again – the more exotic the destination, the better.

Such a column would hold scant appeal, I think, if it were intended as an objective guide to literature, a canon-reinforcing round-up of the greatest works detached from any subjective experience, any life in reading. My intention was both more modest and more self-serving: the column would be about the books that formed me, sentimentally and intellectually, as well as the books that are reforming me now, and even the books that deformed me. I relished the project and wanted to take it further. And so, after the year ended and I moved temporarily back to Ireland, I began to expand it with memories and reflections on books, reading and writing, and the life through which they’ve flowed. As I was doing this, the world changed, suddenly and dramatically, and so the book became about that too – a real-time bearing witness to a vast event whose ramifications, as I write this preface at the outset of a muted, cancelled summer, are indeterminable.

1Svetlana Alexievich

The Unwomanly Face of War (1985)

Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

The Nobel Prize in Literature can be hard to take seriously, but we should be grateful to it for bringing to global attention the work of Svetlana Alexievich. Her first book is a wonder constructed on top of a simple, radical idea: ‘Everything we know about war we know with “a man’s voice”’, but how might war appear when described in the voices of women who lived through it? How does killing feel to beings who generate new life from their own bodies?

In the 1970s and ’80s, Alexievich travelled around the Soviet Union and spoke to women who had lived through – and fought in – the Second World War, recording their experiences on tape and in notebooks. Persisting against wary publishers and hostile censors, she fashioned from these amassed voices a literary form that carried the spiritual drama of great Russian literature into the twentieth century. While Dostoevsky and Tolstoy put the resources of the realist novel at the service of their visions, Alexievich arranges her chorus of voices into a work of non-fictional art. I defy any reader not to be continuously moved by pity, awe and horror as these stories come pouring forth, some lasting several pages, others in mere fragments.

‘I think of suffering as the highest form of information,’ writes Alexievich, before bringing us to the brink of information overload. In our volatile historical phase in which a third world war feels increasingly probable, The Unwomanly Face of War can be read as a primer for a descent into hell. The horror really is abyssal. Yet the strange, sobering revelation of the book lies in how tenderness and pity manifest alongside savagery on every page. The war that Alexievich presents is one of small, piercingly human moments salvaged from oblivion. It is a humbling read. At the outset of her career, Svetlana Alexievich established her mastery of a literary form as majestic, capacious and tragic as Russia itself.

In Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road, while wandering a decimated earth in the aftermath of an unspecified holocaust, the nameless protagonist recalls standing in ‘the charred ruins of a library where blackened books lay in pools of water. Shelves tipped over. Some rage at the lies arranged in their thousands row on row.’ In our own (just about) pre-apocalyptic world, rather than be vandalised in fury at the false promise of meaning they embody, it seems likelier that libraries will gradually vanish from the surface of a connected and digital planet whereon they have come to seem anachronistic, no longer justifying the expense required to keep them open. I may be part of the last generation to whom the library was a place of formation, a resource and a sanctuary. When I was a child, my mother, who left school to work in her early teens, brought me and my brother to the local library, having internalised a radio presenter’s maxim that there is no better gift you can give your child than the gift of reading. As a teenager I would return to the same library to borrow cassette albums (thus discovering The Smiths and Public Enemy) or order in books by Sylvia Plath and William Burroughs. A decade later, the libraries of north-east London provided me not only with stacks of books, but with a workspace. Living in a shared house near Finsbury Park – and when I say shared, I mean there were nine of us crammed into that semi-detached dump – it was not possible to write at home. The fact that one of my flatmates was an unemployed Bulgarian DJ who blared his skull-pounding trance from dawn till dusk was a factor. I wrote my first novel in Stamford Hill Library, cycling there daily with my laptop and a flask of coffee after I got home from work. Unemployed or homeless people likewise frequented the place, reading the newspapers or studying. I’m convinced that the blackness of that first novel of mine was in part a symptom of my Raskolnikovian pique at dwelling in that squalid house with those noisy Vulgarians – but how much blacker it would have been had I no library to go to! If books themselves are to disappear as physical objects, raptured up into the digital immanence, then rather than do away with libraries altogether, perhaps we ought to leave them standing, denuded of books but valued as sanctuaries of silence, honouring Nietzsche’s contention that in a post-theistic epoch, churches should no longer hold a public-architectural monopoly on reflection and solitude.

2 Roberto Bolaño

Antwerp (1980)

Translated by Natasha Wimmer

Long before he attained world fame, the Chilean author Roberto Bolaño wrote a very short novel that was so weird he didn’t even show it to any publishers. In a preface written when Antwerp was finally published twenty-two years later, Bolaño suggests the frazzled condition from which it had emerged – ‘My sickness, back then, was pride, rage and violence… I never slept’ – before affirming the credo that makes him such a seductive a figure to the young, the idealistic and the damned: ‘I believed in literature: or rather, I didn’t believe in arrivisme or opportunism or the whispering of sycophants. I did believe in vain gestures, I did believe in fate.’

Antwerp consists of fifty-six numbered and titled fragments, which do not so much tell a story as hint at the existence of one that blew itself apart and left ghostly, radioactive traces. Images recur: waiters silently traversing a windy beach; deserted highways and hotels; ‘cops who fuck nameless girls’; a hunchback in the woods. A writer, ‘Roberto Bolaño’, flickers in an out of view, prey to hallucinations and disembodied whispers. The effect is totally disorientating and incredibly haunting. Bolaño throws his lot in with the core surrealist technique of juxtaposing startlingly incongruous elements. Narrative logic is shoved out of the speeding train. What remains is a trance of pure atmosphere, the universe as perceived by a shaman in the throes of delirium tremens.

In Bolaño’s subsequent work the sensibility remained intact, but he came to his senses and began telling coherent stories, and they are very good. He always wrote, to use his own phrase, ‘like a madman imitating a madman’. But Antwerp stands alone. It is a mysterious work, like a dream that confounds us on waking, suggesting depths beyond our knowable selves. It is also funny, like all Bolaño’s work, even if the only ‘joke’ he cracks is a punchline that swallows its own tail: ‘Remember that joke about the bullfighter who steps out into the ring and there’s no bull, no ring, nothing?’

What is it we’re reading for? I mean, why do we keep reading and rereading a particular novelist? When I think about Bolaño – and I think about him often – invariably I find my way to the conclusion that what I’m primarily in it for is friendship. That may sound corny, but there is no word that better conveys how I experience my relationship to his books. Admittedly it’s a capacious, suggestive, not very literary-critical word. I could be more rigorous. I could say, for a start, that I love the way his mind works, its kinks and swerves and its boundless perversity; or, that I’m enthralled by his sense of humour as it manifests on every page in that uncommon fusion of mania and control, fanaticism and cool; or, that his novels and stories demonstrate to me a wholly different way of writing prose – looser and more intuitive, less rational or exact, wherein redundancy, commonplace, deadpan non-sequitur, metaphoric unspooling, erratic cliché and pretension are all tolerated within the broader poetical economy of a sentence – as if Bolaño were the culmination of an exotic tradition parallel to the Anglophone writing that otherwise shaped my sensibility, which of course he is. And all of that would be true. But the simpler truth is that I just like being around his books, in the same way that you cherish the company of a person you love, a friend.

3 Fyodor Dostoevsky

Notes from Underground (1864)

Translated by Andrew R. MacAndrew

Is it preposterous to suggest that Fyodor Dostoevsky prophesied the election of Donald Trump, Brexit and the seething hate-pits of social media? Notes from Underground is a vicious slap in the face to the delusion that man is a rational being who acts in his own self-interest. Dostoevsky’s abject, cringing narrator, cowering in a basement hovel in St Petersburg, insists that humankind would rather tear itself apart than submit to boredom or obligatory happiness. The novel is a scream of human perversity, and the most unflinching study of self-loathing in the canon. As such, it is a vessel for painful self-knowledge. Rereading it now, I see myself as I was at twenty: odious, tortured, consumed by rage, obsessing over perceived slights, compelled to act in incomprehensible ways while veering between feelings of worthlessness and a monstrous arrogance.

Notes from Underground pulled back the rock to uncover a festering sub-layer of society whose existence literature had hitherto failed to acknowledge. To Dostoevsky, such tormented wretches as his underground man, who finger their wounds until their thoughts grow sick and dangerous, are the inevitable consequence of a liberalised society that rejects tradition and religion, promising unlimited glory to the individual only to subject him to humiliating material conditions. Today’s underground man is the high-school shooter, the incel, Mohamed Atta, Anders Breivik, the online shamer, the self-hating troll. The underground man loathes everybody around him, because they are his mirrors. Like Notes from Underground, his days are an unrelenting ordeal of envy, spite, impotence, rancour, dissipation, vengefulness and shame.

As the novel opens, the narrator is forty – ‘deep old age’. He is painfully sensitive, ‘as if I’d had the skin peeled off me, so that contact with the very air hurts’, and is still obsessing over humiliations he suffered when he was twenty-four. The only thing he has going for him is his lucidity, which is no comfort at all. He knows he is sick and hopes it gets worse, because after all, ‘man adores suffering’.

Freud described a ‘latency period’ in sexual development, but there also exists – or there did in my case – a latency period in reading. For a gap of several years between a certain point in childhood and a certain point in adolescence, I didn’t read a single book, fell entirely out of the habit. Previously, I’d been an avid reader. I look back on that early book-loving period as a state of innocence, a readerly Eden. As a child I read purely for pleasure; there was no effort, no sense of mission or obligation. I would become absorbed in a narrative, not impatiently projecting forward to what I might read next, nor taking notes, nor underlining, nor trying to remember. I read naively. And then I stopped reading, turning to other interests, namely video games and televised football. I played Doom and Command & Conquer with the rapt concentration I had formerly trained on Roald Dahl’s The Witches, Stephen King’s The Green Mile series or The Chronicles ofNarnia. Later, when I was about fifteen, I made a conscious decision to read again. From this point on, reading became a project, a campaign of simultaneous self-creation and self-destruction. I don’t mean to suggest that I never again read for pleasure, only that the pure, unselfconscious absorption was lost. Post latency-period, I would read a book in part in order to have read it – not merely in a pretentious, status-conscious way, but in the sense that each book added a new tile to a never-to-be-completed mosaic of comprehension. Books became nodes in a network, existing in relation to one another – no longer the singularities of childhood reading, each book sufficient unto itself.

4 Marguerite Duras

Practicalities (1987)

Translated by Barbara Bray

When she was in her early seventies, the French novelist Marguerite Duras spoke to the writer Jérôme Beaujour about a range of subjects and memories that preoccupied her. Duras’ musings were transcribed, she edited them, and the result is this consistently interesting book of miniature essays, autobiographical fragments and aphoristic reflections. Although Duras insists on the work’s limitations – ‘At most the book represents what I think sometimes, some days, about some things… The book has no beginning or end, and it hasn’t got a middle either’ – for my money it’s at least as valuable as the fictions that ensured her renown. In a sense, it’s a pity that authors must first prove themselves with the kinds of work – novels and short stories – that we consider the imprimatur of talent, before the publication of books like Practicalities becomes feasible. Relieved of the obligations of narrative and setting, such secondary works offer a more direct intimacy with an author’s consciousness.

Practicalities might have been titled Marguerite Duras Talks about Whatever Comes into Her Head