7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

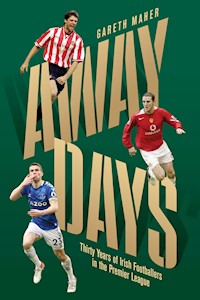

Over the last thirty years, the English Premier League has grown to become the richest and most popular league in football – and the Irish have been at the heart of its success since the very beginning. In exclusive interviews with thirty former and current players, and an in-depth analysis of Irish players' involvement, Gareth Maher celebrates the astounding contribution that the Republic of Ireland has made to the most famous league in the world of sport. With insights from Seamus Coleman, John O'Shea, Niall Quinn, Shay Given, Jonathan Walters, Richard Dunne, Andrew Omobamidele and many more, Away Days uncovers the good, the bad & the ugly of a league that has been home to almost two-hundred Irish players. This is the story of Ireland's impact on the Premier League as told through the experiences of the players who have lived through the title wins and the relegation scraps, the big-money moves and the cancelling of contracts, the villian's disdain and the hero's acclaim over three whirlwind decades.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

About the Author

Gareth Maher is an award-winning former journalist who is now Communications Manager with the Football Association of Ireland. A media officer at five different UEFA European Championships, he designed the award-winning National Football Exhibition and has spent his career promoting Irish football. He was the ghostwriter on Clare Shine’s Scoring Goals in the Dark (2022).

AWAY DAYS

First published in 2022 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Gareth Maher, 2022

The right of Gareth Maher to be identified as the author of this work and the author of the introduction, respectively, has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-869-2

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84840-870-8

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

Contents

Introduction

1 Niall Quinn

2 Ray Houghton

3 Jeff Kenna

4 Keith O’Halloran

5 Gareth Farrelly

6 Alan Kelly

7 Alan Moore

8 Shay Given

9 Matt Holland

10 Stephen McPhail

11 Thomas Butler

12 Rory Delap

13 Richard Dunne

14 Stephen Elliott

15 Stephen Quinn

16 Paul McShane

17 Stephen Kelly

18 John O’Shea

19 David Meyler

20 Stephen Ward

21 Jonathan Walters

22 Paddy McCarthy

23 Kevin Doyle

24 Seamus Coleman

25 Glenn Whelan

26 Matt Doherty

27 Mark Travers

28 John Egan

29 Enda Stevens

30 Andrew Omobamidele

Statistics

Acknowledgements

Introduction

It is often advised not to meet your heroes for fear of being disappointed. Perhaps the failure, though, is understanding who the real heroes in our lives are. For me, it has always been, and always will be, my dad.

Sure, I had posters of my favourite footballers plastered over my bedroom walls and stacks of books by the writers who have inspired me. And I’ve been lucky enough to meet a lot of those people. But none compares to the one man who has been my most trusted counsellor, coach and confidant.

My dad never played football for a team yet he is by far the most intelligent observer, analyst and commentator on the game that I have yet to come across. He sees things differently, always has, and that enables him to simplify things in a world that can at times get caught up in trying too hard to impress. Dad calls it how he sees it and he is rarely wrong in his assessment – but never in a boastful way.

It is quite amazing that the person who, I feel, knows more about football than the hundreds of players, coaches, managers and analysts I’ve worked with is someone who is selft-taught and never played the game. That is the beauty of football; it can be interpreted and consumed in so many different ways.

When the Premiership first launched in 1992, it was like a circus had rolled into town. It was loud, colourful, packed with foreign attractions and thoroughly entertaining. I was hooked immediately. Except I didn’t have a club to support. My brother, Mark, didn’t want me lurking in his shadow so Liverpool was out of the question, while everyone else seemed to be Manchester United nuts. I didn’t fancy following the crowd so I needed to find another club and eventually landed with Arsenal.

It would be some years later before I would become besotted with the League of Ireland, but you never forget your first love and that was the Premier League. I can remember swapping stickers with friends in the schoolyard, playing out on the street until daylight expired and Dad whistled to signal time was up, flicking through Match and Shoot magazines, learning everything that I could about every player at every club and watching all the live games, no matter who was playing.

When my brother brought me to Highbury for the first time, I felt like I was in the original version of Fever Pitch. The atmosphere was incredible. I became even more obsessed with football. And I started to write about it at every opportunity. In fact, I won a writing competition in primary school for a short story on it and my prize was a book by Alan Shearer on how to take penalty kicks. I cheekily asked my teacher, Mr Barry, if he could find one by Ian Wright instead!

I wasn’t good enough to play football at a professional level but that never diluted my love of the game. If anything, it empowered it. The old saying is that if you can’t play, you coach and if you can’t coach you talk / write about it. I was comfortable with option three – even though I did dabble in coaching by earning my UEFA B Licence – and it was something that I made my career from; first in journalism and then working with the Football Association of Ireland.

Working in football has allowed me to meet some truly amazing people. Countless numbers of players, coaches and managers – male and female – have been fantastic in sharing their experiences and knowledge. Work colleagues, such as Stephen Finn, Darragh McGinley and the late Michael Hayes, are people who I could never tire speaking with about football. My brother remains my chief rival in footballing debates and I’m sure my nephew, Luke, will follow in his footsteps. But nobody beats Dad – he is the one who has always stirred up my passion for football.

I’m incredibly fortunate to have had parents who were always hugely encouraging of my two great hobbies: football and writing. Without their support, I would never have got to this stage of writing my first book and being able to shine a light on the Irish players who have made an impact on the Premier League in its first three decades.

This is a book about players and their stories. This is a book about the Premier League. This is a book about Irishmen defying the odds. But most of all, this is a book about falling in love with football.

Gareth Maher

October 2022

1

Niall Quinn

Manchester City (1992–96), Sunderland (1996–97, 1999–2003)

Games Played: 250

Goals Scored: 59

Assists Created: 37

Clean Sheets: 32

Yellow Cards: 26

Red Cards: 1

Wins: 79

Draws: 75

Losses: 96

The revolution will be televised.

Niall Quinn has had inside access to the Premier League on the pitch as a player, in the boardroom as a chairman and in the studio as a media pundit. So when he speaks about the league evolving into one of the world’s most popular brands, he is worth listening to.

When Quinn first left his home in Dublin to join Arsenal in 1983, TV coverage of football consisted of a Match of the Day highlights package on Saturday nights and live broadcast of international games and the FA Cup Final. It was very seldom that a league game would be live on TV. English football was stuck in its traditional ways and being left behind by other European nations who were giving more access to TV broadcasters and tinkering their match schedules to suit their target audience. Something needed to be done to elevate the home of English football back to the top of the popularity polls. That is when the concept of a new top tier, named the Premiership, was first mooted.

From the 1992 season onwards, this new division would represent a fresh approach for English football. It would embrace a step away from the regular Saturday afternoon slot with games set to be spread out over a weekend on Sundays and even Monday nights. Many doubted whether this would be successful, but it was exactly this type of move that had seen American football take over as the dominant sport in the United States.

Years later, Quinn got to understand the Premier League’s strategy when attending monthly stakeholder meetings in his role as Sunderland chairman. He was able to see how television played a significant part in the league’s rise as a global brand. Not that it was all straightforward.

‘I learned that it was very hard to get things done in the Premier League because the clubs kept fighting with each other. It was only when they appointed independent executives, who were not linked to any club, that real progress started to happen and they brought their brand around the world. They also had a partner who knew how this thing worked in America. Sky Sports are always either credited or discredited with bringing the Premier League to where it is, depending on how you look at it. Their owner at the time, Rupert Murdoch, had been all through this before in America and saw how it went into everyone’s living rooms, into every pub and bar. So they followed a well-worn path of how it was done in American sports and Sky backed it. Then suddenly it was all in our faces.

‘The interesting thing is that the matches are the matches, but to put a live feed out twenty-four hours a day about news on football was a huge move. When you think about it, that was a masterstroke. Funnily enough, when I look back at the Irish guys who took on Sky with Setanta Sports, one of the things I felt that they were slow in incorporating was a news feed. By the time they got it up, Sky were ahead of them with reporters outside training grounds and they almost became part of the furniture. One of the key things early on was that there was a feeling amongst the players that Sky were in this to promote it in the best possible light. There was no sense that they were out to do you. And that’s interesting when you look at what way it has gone in recent times with pundits being quite critical of certain players, like Roy [Keane] was on Harry Maguire, for example.’

Still, the Premier League’s embrace of commercialisation through maximising their TV coverage has clearly worked – to the extent that they could boast a global audience of 4.7 billion people as of 2022. The top other leagues around the world wanted to follow suit and still do. The likes of Serie A (Italy), La Liga (Spain), Bundesliga (Germany), Ligue 1 (France), Primeira Liga (Portugal), Eredivisie (Netherlands), Super Lig (Turkey), J League (Japan), Chinese Super League (China), Major League Soccer (United States) and Liga Apertura (Mexico) are all chasing the Premier League for a share of that TV audience.

Granting rights to broadcast games was one thing at the beginning of the ‘Premiership’ era, however; the next was ensuring that the TV companies had exclusive access to managers and players. This was a game-changer in how players would be treated as part of this TV revolution. It was no longer a case of asking nicely for a post-match interview with a jubilant player; instead, designated slots were assigned for pre- and post-match interviews. Failure to comply would result in a heavy fine.

Quinn explains: ‘It was a big change to be told by your club that you have to do interviews. If you say that you didn’t want to do interviews, they would say that you signed a contract and you have to do them. They muscled in on the players’ contracts in theory, but it was all for the showbusiness.’

Once the TV companies had the live rights and the manager/player access, what they needed next was a slick marketing campaign. Sky Sports led the way with the tagline, ‘It’s a whole new ball game’, using one player from each of the twenty-two clubs (Middlesbrough defender Alan Kernaghan was the sole Irish player in there) in a TV advert that had ‘Alive and Kicking’ by Simple Minds as its soundtrack. This was more MTV than ITV, a bold new approach. ‘It had gone like Hollywood, the players were like movie stars,’ says Quinn.

Having joined Manchester City from Arsenal in 1992, Quinn was right in the middle of this new Premiership era as one of its main strikers. He saw how people were sucked in by the marketing, as if Sky had switched on a tractor beam that brought a whole new audience to the top division in English football. And if the marketing was hyped up enough, it could convince people of almost anything – or so Quinn suggests. ‘The power of marketing and the power of looking at football differently to the modern fan and how their perception of football has changed is summed up by Georgi Kinkladze. He played for Man City for three years and won [the club’s] Player of the Century! We were relegated that first year. Don’t get me wrong, he was a lovely player, but it’s amazing that the marketing at that time allowed that to happen. When you think about it, he beat Francis Lee, Colin Bell, Mike Summerbee, all these great players that the legacy of the club was built on, and it was all because of marketing.’

Perhaps Quinn should have tried to avail of that marketing for himself. The 6ft 4in forward could have used his aerial ability to fashion some kind of character that people needed to see. He could have modelled himself as ‘The Premiership’s Greatest Airman’. Okay, there’s some work to do on that campaign, but there is something there, as he was known for what he did with his head.

Speaking of his aerial prowess, Quinn says, ‘I was lucky that that was an important part of the game. Then Jack [Charlton] came along [as manager of the Republic of Ireland from 1986] who loved that kind of thing. I had great timing and that came from Gaelic football because I played in midfield there and you were going up for thirty, forty balls a game. I could tell when the ball was coming how I had to adjust and where I had to be to get it at its highest point, which is actually a skill in itself.

‘In football, it’s all well and good getting up and heading the ball or flicking it on but I had to learn how to pass the ball with my head. Tony Cascarino had what I would call a power header; he could bury it like someone would volley it. But I ended up becoming more of someone who would cushion the ball into the path of somebody. I started playing head tennis when I went to Man City. I wasn’t very good at it [at first] but I became unbeatable at it. And I was unbeatable at Sunderland at it. But a lot of that was deft little headers. I remember one time when Arsenal were playing Sunderland and Arsène Wenger was asked about the game and he threw in a line saying “I’m looking forward to watching Niall Quinn, he’s the best passer of the ball with his head that I’ve ever seen.” At last somebody fucking noticed what I was doing!’

Quinn was much more than a creator of goals, he was a fine finisher in his own right – proved by the fifty-nine that he scored in the Premiership. Yet he is best remembered for his strike partnerships – particularly with Kevin Phillips at Sunderland and Robbie Keane with the Republic of Ireland.

In total, Quinn played in nine top-flight seasons – during which time the Premiership was rebranded as the Premier League – with a couple of spells in the Championship sandwiched in between. He was seen as a good player for Man City but morphed into a cult hero at Sunderland, especially in his final years when he got the best out of himself. ‘My best years were my last five years. That shouldn’t be the case, you should be fading away into the sunset.’

Perhaps there is a touch of regret that Quinn did not ply his trade beyond the Premier League in his later years. ‘Looking back, I should have gone on the continent and travelled for a year or two. I turned down Sporting Lisbon with Carlos Queiroz and later on I was a whisker away from signing for a club in Thailand because I couldn’t get a club at the time because I was coming back from a cruciate injury and nobody wanted to go near me. I would’ve signed for the club in Thailand had Peter Reid [then manager of Sunderland] not made a call. Now, I took a pay cut but I got three years on a contract and I repaid Peter by doing my other knee five weeks later.

‘I was out for eight, nine months and I can remember cleaning out the stables, that my wife Gillian would have kept, listening to the Ireland games on the radio. The Ireland games weren’t on TV at that time so I remember listening to Gabriel Egan and Eoin Hand call games and hoping that they would say that Jon Goodman or Mickey Evans weren’t up to it and that they needed me back in the team. That’s the way football is at times, especially when you’re injured and trying to get back in.

‘Years later, I remember being out in Iran with the Ireland team for the World Cup play-off [played on 15 November 2001]. I wasn’t fit enough to play but to be there and see the team qualify was a fantastic experience. And then we went on to the World Cup in Japan and South Korea. That was all extra-time for me. It was my Indian summer and my most enjoyable time in football.’

On finishing his playing career, Quinn linked up with a consortium of Irish businessmen to take over Sunderland. The club were struggling financially and Chairman Bob Murray was ready to offload responsibility. Even though he had no experience in running a football club, Quinn took it on and began a different part of his life.

It was during those days that Quinn came to appreciate the power of TV and marketing. Some may suggest that is why he appointed former Ireland captain Roy Keane as the club’s manager in 2006. If the Premier League was Hollywood, then Keane was a guaranteed box-office hit. In his first season in charge – and first as a manager – he led Sunderland back to the promised land of the Premier League in the type of way that was befitting of a movie script.

Quinn would move on again in October 2011, this time to the media. He had done some punditry and commentary through the years so he felt comfortable in that chair, opining on a league that he now viewed through different eyes. He still admired the football that was played, but he marvelled at the entertainment product that it had become.

From those early beginnings through to global domination, Quinn believes the Premier League has soared because of its embrace of television. The revolution clearly paid off.

2

Ray Houghton

Aston Villa (1992–95), Crystal Palace (1995)

Games Played: 105

Goals Scored: 8

Assists Created: 12

Clean Sheets: 25

Yellow Cards: 3

Red Cards: 0

Wins: 38

Draws: 32

Losses: 35

Talent is nothing unless it is celebrated. Or, in the case of baseball’s greatest ever slugger, Babe Ruth, unless it is promoted. Arguably the most popular sports star of the 1920s and 1930s, his exploits swinging a bat redounded around the world, largely because of one man: Christy Walsh.

An Irish-American born in Missouri, Walsh was the first ever super-agent to grasp that sports was as marketable as any product that the Mad Men of Madison Avenue would push on consumers. He transformed the public image of Ruth at the peak of his career and therefore altered how middle-class America saw him, how the newspapers responded to him – dubbing him ‘The Sultan of Swat’ – and led to the New York Yankees paying him so much more handsomely than before.

Ray Houghton could have done with the help of Walsh. Of course their careers never overlapped, as Walsh died in 1955, while Houghton debuted for West Ham United in 1979. Still, the sentiment stands that Houghton would have benefitted from having a shrewd agent acting on his behalf to finalise deals and sharpen his public persona.

It’s strange to suggest that Houghton – the man who put the ball in the English net in the 1988 UEFA European Championships and who won five old First Division winners’ medals with Liverpool – needed any help in convincing people of his talent. But he did. And he knows it now.

After the end of the 1991–92 English League season, Houghton had played over 150 games for Liverpool. He was a creative midfielder who scored important goals and brought out the best in his team-mates. He should have been Liverpool’s poster boy for the newly created Premiership but instead he was transferred to Aston Villa that summer.

Forget about humble beginnings, the new top tier in English football was seemingly throwing cash around more recklessly than a gambler at Cheltenham on pay day. Surely Houghton should have profited from this? He was fresh from representing the Republic of Ireland at the 1990 FIFA World Cup and recognised by his peers as someone who had entered his peak years. Yet he needed someone to be broadcasting that to the managerial team in Liverpool to ensure that he was truly valued. Instead he was moved on.

Houghton recalls the period: ‘My last season at Liverpool was one of my best; it was my best goals return, I was voted into the top six players of the year in the top division and I was in the running for being Liverpool’s Player of the Year. So I didn’t feel any reason to leave but it was just that Graeme Souness, who was the manager at the time, wouldn’t pay me the money that I thought I was worth. So that is why I moved.’

The changes brought about by the formation of the Premier League were, for Houghton, clear to see. ‘I think the big change was the money. If you looked at players in England [prior to the Premier League era], the likes of Liam Brady, Mark Hateley, Ray Wilkins, Glenn Hoddle, Trevor Steven, Chris Waddle, they all went abroad for the money. In Italy and France, where the boys went, they were offering more than what they could get in England.’ Then that began to change. ‘It didn’t change overnight because when I went to Villa I probably would have got as much from Liverpool or thereabouts. And it wasn’t as if Liverpool were going nuts paying-wise. I think it took two or three years and then it started, and you could really start seeing the difference.’

Another change noticed by Houghton had to do with agents. ‘They were now heavily involved in football when before very few of them had a lot of say in things. But because of the change in the Premier League and the amount of money that Sky were pumping in, agents wanted to get more money for their clients.’

Born in Scotland, Houghton became a professional footballer in England, first with West Ham, then Oxford United, before joining Liverpool. But his Premier League highlights came in an Aston Villa jersey.

Leaving Anfield for Villa Park wasn’t exactly a step down in standard at the time and Houghton didn’t see it that way either. He embraced the new challenge and quickly established himself as a key player for a team with big ambitions.

‘We actually finished second in my first season. We could’ve done with a little bit more help [with squad depth]. We brought in Dean Saunders after a few games and then we had Dalian Atkinson and Dwight Yorke, so it wasn’t a bad forward line. Maybe we needed a bit more in midfield. There was myself, Garry Parker, Kevin Richardson, Tony Daley, Steve Froggatt. We had a couple of Irish lads in Big Paul [McGrath] and Stevie Staunton. Andy Townsend didn’t arrive until the following season. It was a good move for me at the right time, in the sense that Villa played good football, Big Ron [Atkinson] was a good manager for me and it was the first season of the Premier League.’

Aside from swapping clubs, Houghton didn’t feel any different in 1992 about football in England. Yes, the money started to flood in but it wasn’t until the power of advertising was harnessed by Sky Sports that everyone started to see the Premier League in a different light.

‘I must admit that I didn’t think there was going to be much change other than the name of it. There wasn’t anything to suggest that it was going to go to the levels that it has. Nothing changed with the pitches or the stadiums initially, so it did take some time. But then you had the razzmatazz of Sky. Putting on Monday night football, there was a different appeal to it. You could tell that they were trying to make it into something different than what it was before. That was one of the things that you had to get used to as a player, different days when the football was on … Monday nights, Sundays etcetera. It was a new product in town and they wanted to revamp it. Obviously Sky had paid big money for it, so they wanted to put it on when they wanted it … All of a sudden two or three years into it wages are going through the roof and players are becoming more well known because Sky are showing so many games.’

Whatever about how the game was seen off the pitch, what about the play on the pitch? Did that change much as the Premier League started to grow? Houghton thinks every era should be judged on its own merits and the circumstances of the period.

‘I try not to look at what the 1980s were like compared to today because when I go to football grounds now the pitches are immaculate. You can’t compare oranges with apples. It is what it is today; their training regime is completely different, how they are looked after is completely different, their meals are prepared every day by a chef, so it’s not the same. The players now don’t do long-distance running. We probably couldn’t run at the speed they are running at, but they couldn’t do the long-distance running that we done. You were running in the forest until you were sick during pre-season. They wouldn’t be doing that, they wouldn’t be playing on icy pitches. The pitches now are pristine. At Aston Villa they used to put sand on the pitch and paint it green to make it look like grass!

‘Things did change with tactics and how teams lined up. The 4–3–3, for example, is something that I find difficult to watch with one striker up against three centre-halves. Which of the centre-halves goes to pick him up? How easy is it? And everyone is trying to make out that’s it’s bigger and better than it was before. There are teams like Liverpool and Manchester City who play football in the right way, but there are a lot of other teams who I find it hard to watch. The standard is not always great.’

Houghton has to watch it, though, because he is now in his second career as a media commentator/pundit. It is a job that suits him and one that he has excelled at due to his unrelenting love of the game.

For a man who has the unofficial freedom of every pub in Ireland, where a cold pint is on offer to thank him for Euro ’88, Italia ’90 and for chipping Italy goalkeeper Gianluca Pagliuca in the opening game of the 1994 FIFA World Cup, he prefers to look forward than wallow in past glories. He could go on about Villa’s title challenge with Manchester United in the initial 1992–93 season, or winning the League Cup in 1994, but they are done now. They belong in the scrapbook, along with his brief stint with Crystal Palace that marked his last involvement in the Premier League.

Yet his view on how the league has evolved is interesting. Apart from increased wages and the influence of agents, what would be some of the noticeable differences that he sees in today’s Premier League when compared to his own era?

‘I think the size of the backroom staff at each club is greater than it ever has been. You go down to the pitch before a game and there are more staff members than players! In my time at Liverpool we didn’t even have a physio, it was just Ronnie Moran and Roy Evans who would help you out if you had a problem. Now every club has its own full-time medical staff, including their own doctor, and even a psychologist so that the players have access to that if they need it. The players don’t want for anything anymore and that’s how it should be. There are also other things like a player liaison manager who will sort everything out for players. There is always someone on the end of a phone call, whether that is someone at the club or their agent. If the lightbulb needs changing the agent will get someone to come round and do it for them.

‘I wouldn’t know the extent of it, but certainly the amount of commercial stuff that the superstar players, like Cristiano Ronaldo, do is huge. I started to notice that coming in around about 2001. There was a lot more players doing that sort of thing. You wonder how much leeway they get to do that when it comes to training and the preparation for games. During my time you wouldn’t have been allowed to do that. At Liverpool, it was a case of training then go home, put your feet up, don’t go shopping, don’t go golfing, don’t do this, don’t do that. It was literally train, rest and get ready for the next game. Whereas today footballers do an awful lot more.’

Footballers doing more or seen to be doing more? The work of Christy Walsh lives on.

3

Jeff Kenna

Southampton (1992–95), Blackburn Rovers (1995–99, 2001–02), Birmingham City (2002–04)

Games Played: 290

Goals Scored: 8

Assists Created: 20

Clean Sheets: 70

Yellow Cards: 15

Red Cards: 0

Wins: 97

Draws: 82

Losses: 111

Honours: Premier League

Walk in through the main doors, take a sharp left in the reception foyer, go up the four marble stairs that have been scarred with cracks that look like fault-lines in the aftermath of an earthquake, reach the start of a long corridor where the overhead light flickers, follow the grubby tiled floors that not even Mr Sheen could bring back to life and then stop at the last door on the left.

The door is old, its hinges carry the shade of rusted red, the window is cracked and has the scattered remains of a sticker in the bottom corner. Inside is a classroom that can fit thirty students, with five desks each lined up in six rows. There is a larger desk and a single chair for the teacher, with a blackboard drilled to the wall and a wooden crucifix with the son of God placed above it – looking down on his disciples every day.

In the first row, closest to the wall on the east side of the room, there is a desk with a special marking. You won’t spot it at first glance, so you need to move closer to identify the inscription and authenticate it. But there it is, in black ink, on the right side:

Jeff Kenna was here.

‘Well, I certainly don’t recall doing that,’ claims Kenna when told about the marking. ‘I wasn’t that type that I was doing that sort of stuff so I’m going to blame it on somebody else.’

Perhaps the crime was committed by an old class-mate or some student years later who wanted to remind everyone that the guy playing every week in the Premier League once went to the school. Maybe it was an attempt to inspire someone into thinking that they too could follow a similar path. Or maybe it was just petty graffiti done out of boredom during one painstakingly long afternoon.

Still, it remained on that desk for many years as O’Connell School, off the North Circular Road in Dublin, took their time when it came to upgrading their facilities. The old Christian Brothers school is steeped in history. Named after its founder, Daniel O’Connell, it boasts many successful past pupils, but the ones who really make its students take notice are those who went on to play professional football. Kenna is its only Premier League winner, to date, but he was followed by John Thompson, Stephen Elliott and Troy Parrott in becoming Republic of Ireland internationals.

The fact that Kenna went to school there in the first place is odd. He was from Palmerstown, a suburb in west Dublin, so it required quite a trek each school day to get across the city via two bus journeys. The eldest of six kids, Kenna had two of his brothers – Thomas and Stuart – in tow as they were in the primary school across the school yard when he was attending the secondary school. That was the daily routine until he reached sixteen, completed his Inter-Cert and went off to join Southampton.

It wasn’t a surprise when he eventually left Dublin for the south coast of England because he had been travelling back and forth on every school holiday since he was twelve years old. The club were determined not to let this talented Irish kid slip away after first spotting him in a summer tournament playing for Palmerstown Rangers. He signed a youth team contract, scrubbed the boots of senior player Chris Wilder, and did his best to impress as a midfielder.

Everything changed during a summer tournament in 1990 when he was with the senior team in Sweden and the regular right-back went off injured during a game. Kenna filled in. Little did he know that this would lead to his senior breakthrough with the Saints, who he became a Premier League player with in 1992.

Within three years, Kenna’s star had risen so high that Blackburn Rovers felt that he was the missing piece in their title-chasing team. And when their manager, the great Kenny Dalglish, comes calling it is difficult to say no. A Liverpool legend as a player and manager, Dalglish had been brought in by the club’s millionaire owner Jack Walker in October 1991 to initially return Rovers to the top division for the first time since 1966, and once that was achieved, break Manchester United’s dominance by winning the Premier League. So there was no expense spared, especially when it came to the recruitment of players.

Kenna explains it all: ‘What happened with the move to Blackburn was Alan Shearer and Tim Flowers had gone from Southampton to Blackburn. They were in the England squad when Ireland were playing them in a friendly in Lansdowne Road – the one that got abandoned. Well, that was my first time in the international squad. And that’s when Shearer said to me: “I’ll see you soon.” I said “What are you talking about?” Him and Flowers were winding me up.

‘In hindsight, I knew what was coming. The next thing was that it was in the papers that Blackburn were looking at me. Nothing official got said and then I was at home one afternoon when I got a phone call from Alan Ball, the [Southampton] manager, saying that I needed to come in, that they needed to speak to me. Straight away I’m thinking “Am I in trouble? What have I done?” They said that they wanted me to stay and offered me a new contract but they had agreed a fee with Blackburn Rovers and I had permission to speak to Kenny Dalglish. So I said that I would like to speak with him and see what he had to say. And it went from there.’

In truth, there was little real inner turmoil for Kenna in making the decision. ‘Kenny is an absolute legend of the game. The fact is that they were up at the top of the league and they had been up there challenging for the two seasons. It was a no-brainer. I loved my time at Southampton and they will always have a place in my heart, but the reality is that we were constantly fighting against relegation. This was a chance to work at the other end of the table. And I also had international aspirations. It was a big project that they were building at Blackburn and I bought into it.’

The switch happened in March 1995 – in the days before transfer windows were put in place – and that meant that Kenna could only feature, at maximum, in nine league games. That was one short of league rules for earning a winner’s medal. However, the club promised that he wouldn’t miss out should they clinch the title – something they did achieve on the final day of the season at Anfield. They lost to Liverpool but that didn’t matter as their closest rivals, Manchester United, dropped points against West Ham United.

‘If you look back at that game we should have been out of sight. We had chance after chance but couldn’t put them away. And I remember thinking: “Oh no, have we blown it?”,’ recalls Kenna. ‘Thankfully it worked out in the end. We saw our bench jumping up and down because word had come through of the Man United result. For all of the work and the performances that the team put in all season, it came down to the final day and what a day. In the end, it felt like it was written in the stars for us.’

Decades later, Kenna can still remember the aftermath clearly. ‘The Liverpool fans stayed and applauded us, so that was pretty cool. Obviously they were delighted that Man United hadn’t won the league, so they were just as happy as we were. And at that time Liverpool were sponsored by Carlsberg so I remember them bringing in crate upon crate into the dressing room. It got sprayed everywhere, everyone was buzzing. We went straight from the ground to a place in Preston, still in our tracksuits. There we had a real proper celebration with people up on tables, lots of dancing and plenty of alcohol consumed. The celebrations went on for a couple of days; as you can imagine, the people of Blackburn were only too happy to allow us come drink in their pubs. We knew of the criticism, that people were saying that we bought the league through Jack Walker’s money. And there is no denying that that had a significant influence on things, but the players still had to go out and earn it.’

The next few years did not deliver anything near the high of becoming a Premier League winner, but Kenna still went on to play in a lot of important games, including the following season’s Champions League, and felt the pride of representing his country on twenty-seven occasions. Still, reaching the summit of the league – one which was quickly establishing itself as the best in the world – for a second time proved to be beyond him. In fact, he was part of the Blackburn team that suffered relegation from the Premier League in 1999. Injuries certainly didn’t help his form during this time and he had to undergo two operations during a frustrating period that saw him swap Lancashire for the Midlands when he joined Birmingham City in 2002. That was a fresh chance of playing in the Premier League again with the newly promoted side, and it was one that Kenna enjoyed.