14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

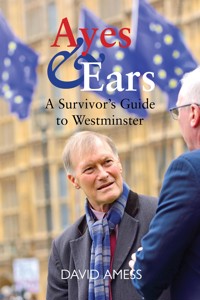

David Amess has been at the heart of British politics for almost four decades. He has witnessed unprecedented changes in technology, the economy, parliamentary procedure, the state of the Union and the European Union. In this book he reviews the major scandals and events of this time and reveals the inner workings of Britain's most important institution. David opens up the world of Westminster for us to explore, to wonder at the historic traditions and to examine the myraid changes which have taken place.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 435

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

SIR DAVID AMESS was born in the East End of London in 1952 and has been a Member of Parliament for 38 years. He stood in the Labour stronghold of Newham North West in 1979, before winning the Basildon seat from Labour in 1983. When his seat was broken up in a boundary review, he was elected to Southend West in 1997.

He was Parliamentary Private Secretary to Edwina Currie, Lord Skelmersdale, and for nine years to Michael Portillo through most of his Ministerial career.

A lifelong animal lover he has campaigned on many animal welfare issues and introduced the Protection Against Cruel Tethering Act for horses, ponies and donkeys.

In 1999 he was successful with a Bill to create a programme of action for home heating and the reduction of fuel poverty, which became the Warm Homes Act 2000. He was a member of the Health Select Committee for ten years.

Sir David is a member of the Speaker’s Panel of Chairs and is Chair of a number of All-Party Groups including Fire Safety and Rescue, Maternity, Liver Health, and Endometriosis.

David Amess’s reflections on the deep and often disorientating changes in politics are essential reading, his insights into his fellow practitioners are filled with charm, and he lays out the triumphs and tribulations of his long life in politics with humour... David is a survivor, one of the most senior and honoured politicians in the land but he has never turned his back on his working-class roots.

MICHAEL DOBBSauthor of the House of Cards trilogy

David is one of those MPS much loved by his constituents because they come first and foremost. His battle to make Southend a City has been a grand source of entertainment for many years – as this book will be – because he’s contributed to public life for so many years.

JEFFREY ARCHER, author

David Amess rose to prominence with a grin: one of the largest ever shown on British television. When his victory in Basildon in the 1983 general election was announced, he abandoned the self-discipline that had kept his expression in check till the official proclamation, rocked back and beamed with joy. It was as emblematic of that great Tory landslide, as the loss of my seat in 1997 was symbolic of the Conservative rout that year.

Thereafter, David maintained his prominence by working into every one of his interventions in the House of Commons the name Basildon; delivered so loudly that the most senior Members whiling away the afternoon on the green benches were startled from their slumbers.

If David had squeaked in on a Tory avalanche, he was not going to be washed out on a Labour thaw. He dug into to his constituency and using his popularity and political acuity swerved constituency boundary changes to end up in a more secure seat.

While I trotted around various ministerial jobs, David followed me as my parliamentary private secretary. He knew the House of Commons intimately and loved it. He was therefore extremely useful to me, offering advice, mounting operations and watching my back against the plentiful Conservative daggers aimed against it.

We met up with a number of nervous Tories defending their seats during the 1997 election campaign. David was despondent, smelling the exit from parliamentary life. But it wasn’t he who was on the way out, but I. That’s 23 years ago and he is still there.

It’s lucky that he entered young because his parliamentary service is now outstandingly long. Goodness knows how many Members have come and gone while he has continued so ably and loudly to represent his constituents.

I am not surprised that there’s material for a book and it makes for very good reading.

MICHAEL PORTILLO,journalist, broadcaster and former MP

Luath Press is an independently owned and managed book publishing company based in Scotland, and is not aligned to any political party or grouping.

All royalties generated from sales of this book will be shared equally between Endometriosis UK, the Music Man Project and Prost8 UK. More information about these charities and the work they do can be found at the back of this book.

I dedicate this book to my late parents, Maud and James Amess, who are entirely responsible for the journey I have been on. Also, to my wife Julia and my children: David, Katherine, Sarah, Alexandra and Florence.

First published 2020

ISBN: 978-1-910022-34-4

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

Text and photographs (except where indicated) © David Amess 2020

Contents

Acknowledgments

Preface

Introduction – Humble Beginnings

Part 1 – Welcome to Westminster

Part 2 – Elections

Part 3 – Outside the House

Part 4 – The Future

Part 5 – Postscript

Glossary

Acknowledgements

I WOULD LIKE to thank the following people who have helped in so many ways with the production of this book: my first secretary, the late Miss Marjory Shearmur, who spent many an hour on a golf ball typewriter, listening to me drone on about my life; the late Mr Lionel Altman, who was my rock and ran my office for many years; Paul Lennon, who has been my unpaid researcher throughout most of my time in Parliament; Paul Pambakian; Phil Campbell; Charlie Spellar; Luke Driscoll; Mark Woodrow; Edmund Chapman; and Gill Lee, my long-suffering secretary.

Preface

THE EVENING OF 9 June 1983 was without question the highlight of my political life. There I was, standing on stage being announced as the duly elected Member of Parliament for Basildon. It was a dream come true and something achieved against all the odds. It turned out to be the biggest political turnaround in that election, and yet not even one junior reporter was there to cover it!

Just four weeks earlier the local elections had taken place and the Conservatives had gained 28 per cent of the vote compared to Labour’s 58 per cent. Elizabeth Dines, my one and only Conservative Councillor, had also lost her seat. I had never seen victory conducted in such a manner: the jubilance of the local Labour Party stays with me to this day. Arms interlinked, they sang as red flags were hoisted either side of the stage. It seemed a pretty insurmountable mountain to climb. Julia, my then fiancé, had certainly not been expecting to marry someone who was an MP. In time maybe, but she hadn’t thought I would be elected when I was.

I will never forget the excitement, bewilderment and thrill of those heady times. When, a few days later, my supporters and I triumphantly boarded a coach to Westminster it was with trepidation as to how I might cope with my new role. I kept asking myself, how could someone like me, born into relative poverty and with no great political helping-hand, become a Conservative Member of Parliament. In hindsight, my upbringing was the making of me and I had everything to thank my family for. I was undoubtedly in awe of – and quite possibly overwhelmed by – the high esteem in which I held the Palace of Westminster and elected politicians. Decades later my feelings at being re-elected as an MP for the ninth time could not have been more different.

In 2017, most people assumed that I would be comfortably re-elected, and indeed I was. In 1983, I had to fight in a completely different way. I was totally inexperienced, without a doubt I was naive and I had nothing to lose. The leader of my party and the then Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, was most certainly responsible for my victory. Her dominant personality created opportunities and continued to do so in all the elections that she led.

The same cannot be said of 2017. My very new Prime Minister, Theresa May, came to lead the party under quite extraordinary circumstances. A referendum, which had given the wrong verdict from David Cameron’s perspective, had catapulted the country into complete chaos.

While the 1983 election was a little early, it was more or less expected. The timing of the 2017 vote was a total shock and without precedent. When I stood on the podium at my count in Southend West, I had the opposite feelings to those of 34 years beforehand. I was not excited; I was not bewildered. When I returned to Parliament, I could not have been more underwhelmed by all that greeted me. The reality was that everything – the institution, the job, the people themselves – had all changed, and not universally for the better.

This book describes those changes and the events which made them happen. While it will be inevitably informed by my own experiences and shaped by my journey into politics, I believe it would be a little premature to write an autobiography. This book is far more concerned with the complete sea-change that has taken place in politics over the 37 years I have been an MP. The leaders, the procedures, the elections and the issues.

I hope this will be a testimony to historical events, interrelating the past, the present and the future in a way that is exercised far too little in our modernistic society. I hope to open up the world of Westminster and shine a light on issues in a way that readers have not seen before.

Introduction – Humble Beginnings

IT IS IMPOSSIBLE to begin writing a book of this magnitude and significance without introducing myself properly to the reader. It was a combination of my own humble beginnings and the force of nature that was Margaret Thatcher that informed my political perspective and resulted in my journey into the Conservative Party.

I was born on 26 March 1952 at Howards Road Hospital, Plaistow, the son of James Henry Valentine Amess and Maud Ethel Amess. Both of my parents came from relatively poor families. My mother, one of 11 children, was raised initially in Bow, within earshot of Bow Bells. In true cockney fashion her family then moved to a place in Studley Road in Forest Gate, where my grandfather had a sweet shop. It was the classic upbringing of three-or-four-in-a-bed, and my grandmother endeavoured to earn extra money by charging the window cleaner to keep his ladders in their side entrance.

My father left school at an early age and for most of his life worked as an electrician for the London Electricity Board. During the war he drove petrol tankers to various army camps, and it was during this time that he met my mother, who had volunteered for the Women’s Land Army. 28 Leonard Road, Forest Gate would eventually become the family home. My father had purchased the property for his parents and when they died our small family moved in.

My children laugh in disbelief now, but I was born into a less well-off family. At the time it seemed perfectly normal, but we lacked many of the modern amenities that people today take for granted. We had no bathroom, no inside toilet, no refrigerator, no telephone and we certainly had no car. Instead, we had a tin bath hanging on the outside wall, an outside toilet and a larder. Despite this, my childhood memories are overwhelmingly happy ones. My mother more or less ran an open house and always seemed pleased to see people. She would walk me two miles to and from St Anthony’s Catholic Primary School every day. We would always have wonderful Christmases, visiting grandparents on Christmas Day and my mother’s brothers and sisters on Boxing Day.

One of my earliest memories from primary school was a tangle with authority. My first teacher, Miss Gray, believed I was a distraction to others in the classroom and asked to see my mother. She told her that I had severe learning difficulties and that despite having a lot to say for myself, I was unable to communicate it effectively. This was due to my speech impediment, meaning a slight stutter and severe difficulty pronouncing ‘st’ and ‘th’. For the following two-and-a-half years, my mother would religiously take me to the speech therapist at the West Ham Clinic. The fact I can communicate today is entirely thanks to the teacher who originally brought the problem to my mother’s attention and the speech therapist who treated me so effectively. I shudder to think of the difficulties I would have encountered in my chosen career path had this not been tackled so early.

In hindsight, my drive and hunger to succeed were the lasting effects of those early years. I was determined to achieve as much of myself as I possibly could, in spite of the fact that I came from a relatively humble background.

The hard work paid off in my final year of primary school. I sat the 11 Plus, which I passed, and was admitted into the grammar school St Bonaventure’s. It was then, at the age of 11, that I decided to become a Member of Parliament. Terribly sad and unhealthy, I know. The chap who sat next to me in class wanted to become a meteorologist, and we both achieved our ultimate ambitions. During those secondary school years, I stood in the mock elections of 1964 and 1966. I had such big ideas and was so naive that I formed my own political party, The Revolutionist Party. From what I can remember my main policies were to abolish homework and set a national minimum pocket money allowance – as you can imagine I was terribly popular! My public meetings were packed but quite possibly for the wrong reasons, as the gatherings often gave other children the opportunity to behave appallingly and generally riot in the classroom – not too far removed from the House of Commons!

In no time at all, this had all gone to my head and as more and more students persuaded me to hold these meetings, practically every playtime, I got to a point where I found myself standing at the top of a fire escape in the playground addressing a large proportion of the school. Despite not quite being able to find the correct formula for victory, my fascination with politics had begun.

The schoolboy experience of jostling with opponents and changing things for the better meant that I was already learning important lessons. When I burst into tears upon finishing third in the 1964 mock elections, I promised myself to never again be unprepared for the worst, and to never show weakness to your opponent. This attitude resurfaced before the 1983 election count, when I gathered my loyal campaign team and advised them: ‘Look, I think we have come a good second, but when we go to the count, we mustn’t let our feelings show that we are disappointed. Let’s keep big smiles on our faces and then when it’s all done and dusted, we can come back, talk about the campaign and let off some steam.’ Of course, I would go on to win in that election, but my attitude has always been to prepare myself for the worst.

While I understood very little about politics and had no natural inclination towards any of the parties in particular, I quickly realised that The Revolutionist Party was not going to be how I would become a Member of Parliament.

I was very much aware of the physical deterioration of the neighbourhood that I had grown up in. The route from 28 Leonard Road to St Bonaventura’s was changing. The roads were being neglected, the housing was looking shabby and I felt that the environment that I had come to know as a child was changing for the worse. So, I made it my business to find out who was responsible and, surprise, surprise, it was the Labour Party.

The local MP, who had been there for 40 years, did not live in the constituency nor did he hold any surgeries. His name was Arthur Lewis and he has long since passed away. The local council was 100 per cent Labour, as was the Greater London Council (GLC). At this point, it was simple: I had big ideas and I would oppose the current Labour regime.

It was during the spring of 1968 that a newsletter from the Forest Gate Ward Conservative Association Committee dropped through our letterbox. I was now 16 and I read the newsletter, which told of the ward having recently elected three Conservative Councillors for the first time in many years. As I read on, I noticed that the Treasurer of the Ward Committee was a Mr Catton, who actually lived in the house opposite. Although my mother knew the family well, I had taken little notice of him, other than regarding him as being an extremely smartly dressed man who looked a little like the French actor Maurice Chevalier. The newsletter was appealing for members and asked anyone interested in joining to contact Mr Catton. It did not take me long to come to my senses and I wrote to my neighbour expressing how impressed I was with the changes his organisation wanted to make. Everything that was said regarding the state of the borough had really resonated with me. It was clear that the propaganda had worked. I joined the party and have never looked back since nor regretted my decision.

Margaret and Me

So the deed was done and I had made my first move to enter the political domain. It was then that I would begin to encounter and revere my greatest political inspiration.

Without any question Margaret Thatcher, or as she later became known, Baroness Thatcher, was the greatest, most outstanding and most thought-provoking politician that I have ever known in my lifetime. It’s difficult to think of anyone else who has changed our country and the world as much.

I believe that she was a force for good and made our country a better place in which to live. Most of my colleagues now reminisce about Margaret. They were not MPS when she was Prime Minister, they only knew her in later life when her incredible work had taken its toll on her health. I regard myself as being incredibly blessed to have been in Parliament for two of her terms, when she was at her peak, and to enjoy her dominance of Westminster. But how did it all start, the admiration I hold for this great leader?

My opinion of the governments that preceded her moulded my interactions with, and my views of, Margaret. At the time I joined the Conservatives, a Labour government (1964 to 1970) led by a brilliant politician, Harold Wilson, was in power. Sir Alec Douglas-Home, whom I was privileged to meet later in life, had become leader of the Conservative Party in extraordinary circumstances. Harold Macmillan was ill in hospital when he told the nation he could no longer carry on as Prime Minister. He advised the Queen that his successor should be Douglas-Home, which of course could never happen now. Douglas-Home was a lovely man, a real gentleman, but far too nice for the rough and tumble of politics. While he did nothing wrong, he was no match for the wily Wilson who won the 1964 election by five seats. Sir Alec immediately resigned, and the party elected a new leader, Edward Heath.

It is not within my nature to speak ill of the dead (may God forgive me) but I was never fond of Ted Heath. I found him a rather cold and remote figure, but much worse he was a Europhile and that I certainly wasn’t – I was intensely patriotic. When, somewhat surprisingly, he won the 1970 general election, he told the nation that he was determined that we should join the European Economic Community. I was horrified. I felt, even as a post-war baby, somewhat aggrieved at the way Charles de Gaulle had treated Macmillan when we had first applied to join. We had sheltered, protected and rearmed France during World War II, treating him as a world leader long before anyone else did. But this had clearly not been enough for him, and the legendary rebuke of ‘non, non, non’ represented the fundamental difference between the United Kingdom and the rest of continental Europe.

Ted’s premiership was a rather sad affair. He became known for his love of culture, as a conductor and connoisseur of fine arts. In a sporting capacity he also became famous for his love of yachting – sailing with a crew. This was all in stark contrast to the job he had been entrusted with, running the country. It took him no time at all to become embroiled with the unions. There was a pay freeze and an enormous U-turn. Strikes had become the order of the day when he crazily called a general election in 1974 with the battle cry: ‘Who runs the country, the government or the unions?’

To my mind if you ask a silly question you get a silly answer. The British people decided that they didn’t quite know who ran the country and they left Ted Heath’s government short of an overall majority. He made overtures to the Liberal Party leader Jeremy Thorpe to go into coalition. Sound familiar? Thorpe was very close to becoming Home Secretary but unlike one of his successors, Nick Clegg, he was eventually dissuaded by his party’s grassroots who outright refused to have anything to do with a Conservative-led coalition.

The result was that Wilson’s Labour Party came back to power, albeit with a minority government which resulted in another general election being held in October of the same year. Labour were returned with 18 more seats and a majority of three. Ted, instead of resigning as leader as he should have, resolved to carry on.

Margaret Hilda Thatcher had been the only woman in Ted’s cabinet and was Education Secretary. Well-known for her splendid hats but rather plain pinafore dresses, she had a tough time in her position, during which free school milk for primary school children was removed. Her enemies chanted that she was ‘Margaret Thatcher, Milk Snatcher’. As politics so often is, it is just another example of a long career being shortened to one digestible newspaper headline. The reality is that, as cabinet papers have since revealed, she was forced into this concession by the Treasury. What’s more is that it was simply a continuation of Labour’s education policy which had abolished free milk for secondary school pupils in the 1960s.

So, while it was undoubtedly a difficult period for her, it was also an invaluable one. During her time in cabinet she formed bonds with right-leaning intellectuals such as Keith Joseph and Airey Neave and joined a group of politicians who felt that there should be a different leader of the Party. Ted was not only damaged goods but had been taking the country in the wrong direction. The most difficult decision to make was who would lead the challenge. Keith Joseph was felt to be the right candidate, but he declined, leaving a clear run for Margaret. From that moment onwards, Thatcherism as a political force was born.

While I didn’t know a huge amount about her at the time, there was something about her that drew me to support her. The press of course were enthralled at the prospect, however remote it might be, that a woman would be elected for the first time as leader of the Conservative Party. She gained ample media attention, but it was still thought that the contest would be a formality for Ted. How wrong the pundits were. Margaret won 130 votes compared to Ted’s 119 in the first round.

When Sir Edward du Cann, Chairman of the 1922 Committee, announced the result gasps of breath were drawn. Ted was furious and deeply hurt at what he saw as Margaret’s betrayal. He resigned immediately and, in what became known as ‘the longest sulk in history’, he never forgave her. The reality was that she had the guts to take him on at a time when no one else had.

There had to be a second ballot and other candidates came forward. The momentum was with Margaret and so she triumphed. I happened to be at home at the time I heard the result and I could not have been more pleased. By this time, having become the Association Chairman in Newham North West, I was becoming more active in politics and had accrued a growing number of loyal supporters. A small group of us went to her home in Flood Street, Chelsea, and handed over a flower arrangement in congratulation on her election. A new era in Conservative Party politics had started and, although I didn’t know it at the time, it was to shape the future of my political journey.

I stood as a candidate for the GLC elections in 1977 when Horace Cutler was the leader of the GLC. I greatly enjoyed the campaign and, as it turned out, came a very respectable second. I was then adopted as the prospective parliamentary candidate for Newham North West. The vote was close, but I was delighted to have been selected.

By this time the Labour Government had well and truly fallen apart. Harold Wilson had dramatically and unexpectedly resigned, with no one quite knowing why. There was intense speculation, as there invariably is over matters such as this. The conspiracy theorists would have us believe that a rogue department of the security services went after him, thinking that he was a Soviet Agent. They bugged his devices, broke into his friends’ homes and pushed black propaganda to the media, forcing him into an early retirement. Personally, I find the most persuading case to be that Wilson knew his brain was fading and decided to quit while he was on top, before the Alzheimer’s really kicked in. All very sad.

Jim Callaghan defeated Tony Benn in the ensuing Labour leadership contest. I imagine most of my readers will be aware of just how grim the 1970s had been. Commercial users of electricity were only allowed to work three days a week, strikes grew intensely, rubbish was piling up on the streets and we couldn’t even bury our dead. The final humiliation was the then Chancellor, Denis Healey, having to get the IMF to bail the UK out. The irony of a union supported government not being able to prevent ‘The Winter of Discontent’ was not lost on the electorate. Our once proud nation was humbled and at the heart of it all seemed to be the overweening power of the unions. Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition would not let this go unnoticed.

The first time I met Margaret was when central office asked me to appear in a party-political broadcast with her. I was delighted, if not enthralled. Margaret’s likes and dislikes were not always conventional or straight forward. She immediately clicked with a Conservative working-class activist in Thurrock, Ted Attewell. Well-known for his somewhat extreme political views, he was present on this occasion to make the broadcast, which would be filmed at Elstree Studios. Margaret appeared with an aide and we all climbed into something that resembled a campervan.

From the moment we set off, Attewell never stopped talking, jabbing his finger at Margaret and not allowing her to get a word in edgeways – something that would seem most foreign to her in later years. I remember thinking during the ride, my goodness, this woman is incredible. If it would have been me that Ted was ranting at I think I would have bluntly told him ‘shut up for God’s sake’. The extraordinary thing was that when we got to the film studio and it was Ted’s turn to speak, he completely dried up and no matter how many retakes we filmed, he couldn’t get a single word out!

The party-political broadcast itself was nonetheless completed, and even if I say so myself, I thought it got the point across extremely well. It illustrated the debt that Labour had accrued by a ball and chain wrapped tightly around a baby’s foot (or at least a doll’s foot). Under today’s rules, you wouldn’t be allowed to make such an ‘emotive’ film.

By 1979, Callaghan seemed to go from crisis to crisis, even if he refused to acknowledge so. ‘Crisis, what crisis?’ would be a phrase that he would never live down, with celebrities such as Twiggy and the Bee Gees condemning his remarks as those of a silly old man.

The criticism that came his way was damning and Margaret played it to perfection. On the 28 March 1979 at 10.19pm, a vote of no confidence was called in the House. I was excited by the prospect of an election and happened to be at the home of my agent, Joan Short, at the time. The vote hung by a thread, and two individuals in particular would play an integral part in the future of the government. First, it all seemed to depend on whether or not an Irish member would support the government and be dragged away from his pint of beer in one of the Commons bars. Second, Sir Alfred Broughton, who was mortally ill at the time and died a few days after the vote, had been desperate not to let his government down. All options to get him on site were explored, including driving him to Speaker’s Court in an ambulance. A discussion regarding the complications that would have been caused should Sir Alfred have died on his way to Parliament resulted in Callaghan insisting that he did not risk his life.

As it turned out, these two votes would prove crucial as the Government lost 311 to 310. When the Speaker read out the results, Joan and I jumped up and down in joy and hugged one another. We were really excited by the prospect of an election; little did we know how important it would turn out to be.

When the campaigning got going it was a real inspiration. Margaret had assembled an excellent team around her, including the likes of Willie Whitelaw and Sir Geoffrey Howe. There were endless photo opportunities and a real focus on image. Sally Oppenheim-Barnes, the glamorous Consumer Minister, (she still looks glamorous today at the ripe old age of 92) was photographed in a supermarket holding two shopping baskets, one being full at the start of the Labour Government and one being nearly empty at today’s prices, such was the effect of inflation. Maurice Saatchi also launched a brilliant visual campaign with posters of a long queue of people headlined: ‘Labour isn’t working’. This all added to the tide of anger at how the country had been governed and gave a real sense that outright victory was possible.

In my local campaign in Newham I was determined to make a similar impression. While the seat that I was fighting for had always been Labour and returned the first Labour Member of Parliament, Keir Hardie, I was absolutely determined to get a good vote. We had plenty of razzmatazz, posters and balloons, even a procession down the high street, including a float on which sat a beauty queen, Miss Bluebell.

The nation was gripped with election fever. The slogan ‘time for a change’ rang so true. I came a good second in Newham North West and Margaret swept into 10 Downing Street with a healthy majority of 43 seats. She stood on the famous steps of her new home and delivered a carefully choreographed speech, quoting the words of Saint Francis of Assisi:

Where there is discord, may we bring harmony. Where there is error, may we bring truth. Where there is doubt, may we bring faith. And where there is despair, may we bring hope.

These words would be mockingly used against her towards the end of her period in office. The nation was electrified at the prospect of Britain’s first female Prime Minister and again Newham North West Conservative Association sent a basket of flowers to Margaret’s home.

Despite not being elected in 1979, I was privileged to be chosen to represent Basildon in 1983 and then again in 1987, so I was there for two of her three terms in office. It was probably during the first of those that her powers were at their peak. Seeing her in action was a huge influence and inspiration for me. She changed the Conservative Party, our country and the world for the better.

Seeing her at work, I would say that she undoubtedly understood the hopes and aspirations of ordinary people. She was quite different from her predecessors in that she did not come from a privileged background but from an ordinary family who ran a shop in Grantham. Her father was involved in local politics and had been the mayor of the town. Her family were also devout Methodists, but her upbringing was such that she understood the basic concepts which lay behind business – how to beat the competition, how to please customers and how to account for incomings and outgoings.

Margaret’s fundamental principles soon set about changing the way we ran our country. She was horrified at the way the unions had moved away from their original purpose, which had been to secure rights for workers. Margaret felt deeply that the last Labour government had shown beyond any doubt that the union leadership had become far removed from the hopes and aspirations of their actual members. She had witnessed how they had brought down the Heath government and was determined to avoid the same mistakes. So, when she decided that the mining industry had to be reformed, she chose to pick a fight with one of the most vocal and vociferous union leaders, Arthur Scargill. He stood accused of undermining parliamentary democracy and economic performance through consistent strike action.

For many years the mining industry in the UK had been in decline. Mining communities were built and depended upon the work which the mines provided. However, as a result of foreign competition, UK coal mines quickly fell far behind their international competitors. Resulting closures of mines were met with fierce resistance and more strikes by Scargill. By preparing fuel stocks, appointing hard-liner Ian MacGregor to run the National Coal Board and ensuring that police were adequately trained and equipped with riot gear, Margaret had broken their resolve and gave a warning to others that she would never tolerate the country being held to ransom again.

But this was not all she ought to be known for. The electorate were enthusiastic about her policies, and those that she introduced were to be copied worldwide as her fame spread. She defined herself by a radical programme of privatisation. She felt it was an enormous drain upon the public finances to prop up inefficient industries. She combined this with a crusade to encourage ordinary people to own shares. One by one, industries which were formerly in public hands became privatised – electricity, water, gas, telecoms and the railway.

As the MP for the largest new town in the country, I had first-hand experience of the enthusiasm of council tenants, often of long standing, to secure their own homes at a heavy discount. Margaret was instrumental in allowing this to happen. You could always tell when a council property had been bought by the change in the doors and windows. They would be a different colour from the often-bland appearance of those still owned by the council. The windows themselves would also often be removed and replaced with something more modern. The front gardens would invariably be different. The bog-standard council bell or door knocker would be removed and the curtains which adorned the windows of bought properties would invariably be more lavish.

Today Canary Wharf is taken for granted, but for someone like me, coming from the area and recalling the deserted docks only too vividly, it is an inspiration to see what a centre for economic activity the docklands has become. Margaret’s drive and vision made that happen. I recall visiting the old docks with parliamentary colleagues to see the area where London City Airport was planned. A truly amazing concept and one which has been of enormous benefit, not just to Londoners, but for people far and wide.

Among the many and various infrastructure projects which Margaret pioneered, the most remarkable was probably the Channel Tunnel. Who would have thought that Mrs Thatcher, with her sceptical views of the European Union, would have met with President François Mitterrand and agreed to join the UK to mainland Europe? All sorts of obstacles and objections were raised at the time, with some people believing that it was an unachievable project. How wrong they were. I remember only too well walking down the tunnel before its completion with Michael Portillo, the then Chief Secretary to the Treasury, and seeing first-hand the mastery of those who had successfully drilled the tunnel. However improbable it seemed at the time to build a tunnel between the UK and mainland Europe, that is what happened. So perhaps the incredulity with which Boris’ idea of a bridge with Northern Ireland has been met with is a little premature!

There are so many stories that I could regale about Margaret and I will always regard it as an enormous privilege to have been part of the parliamentary party when she set about making Britain great again.

It was often said that she lacked humour and was a workaholic. The latter was certainly true, but the former was not. First of all, Margaret put her femininity to good use. She allowed her image makers to give her not only a make-over in style, but physically too. In time, the gap in her two front teeth disappeared and, although always a smart dresser, she developed her own style: Power Dressing. Well-cut suits, invariably electric blue, with padded shoulders. Her hair was boosted by whatever technique the hairdresser used, but she was always immaculately coiffured. Most importantly of all her voice was changed. She was coached by the very best to lower her tone by an octave or two, the point being that she should sound less shrill.

I believe Margaret relished operating in a man’s world. This was particularly notable when she travelled abroad. In photographs with world leaders she clearly stood out as the only woman and her stylish dress was very distinctive.

Her femininity did not mean she was immune to men whom she perceived to be handsome. Two in particular took her favour: Cecil Parkinson and John Moore. Cecil at his peak looked somewhat like a matinée idol and he and Margaret had a great chemistry together. For that reason, she stood by him to reward his loyalty when he got into difficulties in his private life.

On the other hand, most women judged John Moore to be the one with movie star looks. He was often spoken of as a future party leader. Alas, this did not materialise. When he took over as Secretary of State for Health and Social Security, for some inexplicable reason he kept having problems with his voice. It later transpired that his voice had been ruined as a direct result of the failings of the air conditioning system in the department building at Elephant & Castle. As a Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) in the same department and often the same building, I do wonder whether it ever changed my own.

Back in the Chamber, and especially when Margaret voted in the lobbies, it was as if there was a glow around her. People were in awe of her physical presence. At Prime Minister’s Questions, Margaret was absolutely dominant. She wiped the floor with the hapless, but very worthy, Michael Foot. Foot never recovered from the media drubbing he received when wearing a donkey jacket as he shuffled up to the Cenotaph to lay his wreath on Remembrance Day. It was generally agreed that his poor sartorial appearance was an insult to the fallen.

When Michael was succeeded by the Welsh Windbag, Neil Kinnock, Margaret had an absolute field day. While Neil’s lauded oratory could be appreciated on some occasions, it was not well received in the House. His style could best be described as taking a paragraph to express one sentence. He also managed to mispronounce foreign sounding names or complicated words. Margaret developed a method of turning the tables on him over his party’s policy inadequacies, no matter what he asked.

One myth that I would like to take this opportunity to try and dispel is that Margaret was a bad judge of character. She certainly appointed some very interesting PPSS – in itself an important job. The truth was that she possibly never found another PPS quite as able or outstanding as Ian Gow. Part of the job of a PPS was to ensure that one’s minister was kept in touch with how ordinary members felt. The desired qualities in a PPS are someone who knows everyone, understands their ambitions, their reservations and deals with them before they’ve even had the chance to voice them. Gow would relay all messages to Margaret, no matter how unpalatable. The same cannot be said of all of his successors, the majority of whom were not best placed to relate with fellow colleagues.

The PM would, from time to time, meet groups of MPS and take soundings and suggestions from them about possible policy options. It was only towards the end of her time as premier that she was criticised for being out of touch, not only with the country but her own parliamentary colleagues. John Whittingdale, who had worked for her in Number 10, organised a meeting between her and about ten colleagues – one of whom was me. She sat there taking copious notes. When it got to my turn, I remarked that the government was being accused of running out of steam and suggested that she initiate some new big ideas such as those regarding council houses and shared ownership. She asked if I could think of any and I am afraid to say that my answer was in the negative.

Margaret’s influence was not restricted to British shores. She also had an enormous influence in world affairs where she really became the dominant figure together with the US President Ronald Reagan and the young Russian President, Mikhail Gorbachev.

When Gorbachev became Soviet leader, Margaret enjoyed a new and quite different relationship with her opposite number. Previous leaders could best be remembered for standing on a platform in Moscow’s Red Square, watching military vehicles drive past and soldiers march – rather like the situation in modern-day North Korea. They looked grim and austere figures. Gorbachev was young, vibrant and possessed the ability to smile – a rare feature at the time. As Margaret observed, he was a man that we could do business with.

There was something about this new Soviet leader that was impressive. It wasn’t just his general demeanour. He was undoubtedly highly intelligent and felt a natural warmth towards the West that his predecessors had never possessed. I was invited to meet him early in my parliamentary career. The meeting was organised by the Inter-Parliamentary Union and I was chosen because, believe it or not, I represented the youth of parliament. Indeed, Gorbachev looked at me and said that I was very young to be an MP. I returned the favour by saying that he was very young to be the Soviet premier. It was only in much later years that I came to fully appreciate how incredible the opportunity was.

Margaret also enjoyed an excellent working and personal relationship with Ronald Reagan. They shared the same economic belief in an enterprise culture and the free market. While their characters could not have been more different, they had a great chemistry and undoubtedly cemented the Special Relationship between our two countries.

I’m often asked how she would view modern politics if she were alive today. In some senses, she would be in utter despair and disbelief. By her very force of personality, she would not tolerate some of the nonsense that Theresa May had to cope with. Furthermore, she would be in complete despair at the lack of quality of many of our world leaders today.

In so many countries the leaders appear to be inadequate for the posts that they have been elected to. Margaret would never have allowed the simpering Angela Merkel to dominate in the way that she has and would not have only stood up to Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, but would have hand bagged them into submission.

On another level, she would have been delighted about the result of the EU referendum and while being a very different kind of PM to Theresa May, she would have been fully behind her in her efforts to get the best possible deal for the UK. She would be incredulous at the rise of Jeremy Corbyn to Labour Party leader and likewise would be astonished and appalled at the revival of the far left.

Finally, Margaret would find the House of Commons, as it is today, very odd. I have no doubt she would be saddened by the decline of parliament, with its reduced working hours, the imminent departure from the building itself and the rise of the unelected power of bureaucrats. After all, when she was Prime Minister, questions were held on Tuesdays and Thursdays for 15 minutes. We sat and worked very long hours and bills were not timetabled. Her concerns would be shared by me and I intend to talk about them throughout the rest of this book.

PART 1

Welcome to Westminster

AT THE RISK of sounding like Victor Meldrew, parliament has changed and not always for the better. That said, I entirely understand that as the vast majority of MPS were elected in 2010, 2015, 2017 or 2019 – they have little to compare with the current state of affairs.

Age old traditions vanish with increasing regularity. I find it hard to compare any of the new recruits to those who defined the 20th century. Love them or hate them – Enoch Powell, Michael Portillo, Margaret Thatcher, Tony Benn, Michael Foot, Ian Paisley, Shirley Williams, Roy Jenkins, David Owen (and many, many others) – these politicians all had distinctive personalities. They could be unpredictable, yes, but they were fiery, impassioned and willing to put everything on the line for what they believed in and for the interests of those they represented. They also had the ability to make significant change. Too often I find myself telling constituents that I am unable to create change in the same way that I had done back in the 1980s. Being an MP is not what it used to be, mainly because unelected individuals increasingly pull the levers of power.

It might be that various high-profile scandals have forced this revolution. MPS are less trusted and are therefore scrutinised far more than ever before. Maybe it is just modern life, the increased transparency and accountability (which of course has many benefits) that social media inevitably brings. Every move is watched, every word recorded and silence means laziness rather than hard work. But I am not writing this book to explore why this has happened but rather to explain what has happened, to highlight the differences and peculiarities and to encourage others to reflect on when change is positive but also when it must be fought against.

Inside the House

Procedures and traditions have undoubtedly changed under the banner of modernisation. I suppose to some I could be seen as old-fashioned and living in the past. I would counter that by saying I like tradition. Often evolved over a very long period of time and with good reason, I think it’s tragic to end our unique procedural practices. This is especially the case when the rationale is weak, and the main motivation is to sacrifice for the sake of it at the high altar of modernisation.

The current building, designed by Charles Barry and Augustus Pugin, looks much the same now as it did when it was completed in 1870. The debating chambers had been finished much before then, with the Lords sitting there from 1847 and the Commons since 1852. As a result, the place is awash with history. From Disraeli to Gladstone and Major to Johnson, all modern-day Prime Ministers have been answerable to parliament from the same despatch box. So, while parliament may look the same from the outside, what goes on within its walls would be unrecognisable to my predecessors.

At the risk of being controversial, I miss the camaraderie which was created as a result of the working practices of parliament. We used to sit five days a week. The working day, in parliamentary terms, always started at 2.30pm other than on Fridays. The argument for this was that Government Ministers were Members of Parliament too and it allowed them to get on with their constituency work in the mornings and to deal with departmental matters before the House sat. That may have been true, but there was also certainly an element which involved members having second jobs. For instance, a number of colleagues worked in the legal profession, which meant they would prepare their briefs in the morning, appear in court in the afternoon and still be ready for the votes at Westminster in the evening. Others were accountants or involved in finance. They again would work in the city throughout most of the day and spend their evenings voting. Those MPS who were journalists, writing columns for papers, had more freedom. In recent times, there has been much criticism of Members having second jobs. Despite having to declare their interests, that doesn’t stop the media having an annual ‘pop’ at the outside earnings of parliamentarians. When George Osborne was relieved of his job as Chancellor and returned to being an ordinary Member, there was much fuss made of the fact that he had landed the fabulous job of Editor at The Evening Standard. The cry went up, ‘how can he do both jobs?’ An urgent question was asked on the matter. I was already sitting in the Chamber for a previous matter when George walked in for the start of the question and plonked himself next to me. In one sense it was awkward, in another it was nice to be there to hear at first-hand what was going on. Needless to say, he quickly realised that doing both would not be an option and he chose to leave Parliament which was a great loss.

As the word Parliament (Parli) indicates, the purpose is to talk, to debate and to scrutinise legislation. And so, our proceedings would often continue until 2.00am, 3.00am or even 4.00am. Members today would say this is crazy, what a way to run parliament! How could you have a family life? Well we did and we managed. Members and their families went into politics with their eyes wide open as to what the job entailed.